'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label secrecy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label secrecy. Show all posts

Friday, 26 March 2021

Tuesday, 9 October 2018

Whistleblower Rudolf Elmer on Why a Court Ruling Could Finally Topple Swiss Banking Secrecy

Rudolf Elmer in The Wire.In

Editor’s Note: For nearly 14 years, Rudolf Elmer has tried to chip away at the principle of Swiss banking secrecy, which laid the groundwork for an international system that helped the world’s rich and multinational conglomerates evade billions of dollars in taxes through offshore financial structures and tax havens.

Elmer was the Chief Operating Officer of the Caribbean operations of the Swiss bank, Julius Baer, for eight years before being dismissed in 2002. He was, as The Wire has noted in a 2017 interview, was part of the first wave of Swiss bank whistleblowers who helped expose the inner workings of a patently unjust system.

In 2011, he was tried for sharing information about tax evasion, money laundering and other financial violations with Swiss t0ax authorities and Swiss newspapers.

In 2014 he was tried for sharing information with US, German tax authorities and WikiLeaks. While it’s unclear if the Americans made use of Elmer’s data, in early 2016, Julius Baer coughed up $547 million in fines after the Obama administration filed criminal charges against the bank. The German government went onto levy another EUR 50 million penalty. Both fines were paid instantly in order to avoid prosecution.

Elmer’s crusade has taken a personal toll as well. Due to multiple cases, he has been imprisoned for over 220 days, most of it solitary confinement, and has had to fend off an orchestrated harassment campaign against his family.

In 2016, he won a partial victory in the high court of Zurich, which turned down demands by the prosecution to convict the 63-year-old of breaching Swiss banking secrecy laws, but upheld other less minor charges.

On October 10, 2018, in response to appeals filed by both Elmer and the prosecutor’s office, the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland will take a final call. Elmer, whose as-of-yet-unpublished data also contains the offshore secrets of 20 ultra-high-networth Indian clients, writes below on what’s at stake.

In my view as the accused person, the essence of this highly political and crucial case for Switzerland’s finance industry is if the much-vaunted principle of Swiss bank secrecy can be applied extra-territorially.

In this case, whether the banking secrecy can be applied to entities that operate in the Cayman Islands.

In the Cayman Islands, the Julius Baer Trust Company Ltd. (Cayman) administered trusts, companies, equity- and debt-funds but also hedge funds on a big scale. Some of those special purpose vehicles held Swiss bank accounts with Bank Julius Baer & Co. AG, Zürich in Switzerland.

The statements and other advices associated with those Swiss bank accounts were regularly sent to the Cayman Islands in order to perform administrative tasks for the accounts of those special purpose vehicles.

It is because of these Swiss bank accounts that “Causa Elmer” (Case Elmer) has turned into a “Causa Swiss Bank Secrecy” (Case Swiss Bank Secrecy). It particularly focuses on its future, because the crucial question is if Swiss bank secrecy can protect client data outside Switzerland.

In 2011, when I was in solitary confinement for 220 days, a famous Swiss lawyer wrote me a letter that explains my predicament nicely:

“You are more dangerous to the Swiss Banking system than the Red Brigade or the RAF terrorist group in Germany used to be to the German political system.

The legal proceedings against you are highly politically motivated and driven because it is about the golden calf of Swiss Banking Industry: the Swiss bank secrecy.

Every government protects its golden calves. Therefore, the prosecution offices and the Courts of Switzerland protect the money-making-system and not citizens like you who comes forward and discloses crimes.

Making financial crimes public would hurt in this case not only the Swiss financial system but also on top of it the question arises what would happen to the Swiss Financial Industry if key players in the financial market of Switzerland like UBS, Credit Suisse, Julius Baer etc. would be investigated by Swiss authorities or even foreign authorities. What would clients think about it and would they possibly withdraw their assets?

Therefore, prosecutors and the judges tasks are really not to go after the bank or even after all the violations of the law by Swiss bankers, their true and hidden task is definitely not to investigate certain matters which could hurt the Swiss system but more importantly to go with drastic measure after people like your who made the truth available to the public by publishing matters on WikiLeaks in 2008 and providing information to tax authorities in Switzerland and abroad.

Even worse, your case should demonstrate to the Swiss society that whistleblowing in Switzerland will eventually lead to the social, financial and professional death and is simply a no-go in the secret society of Switzerland”.

This also tells me why the entire legal case, which was opened under dubious circumstances in 2005, has been investigated and re-investigated several times.

The judges of the Higher Court of Zurich acted even as a supervisor of the Prosecution Office and provided guidance. A materially changed indictment was issued in 2013, roughly 70 court rulings were issued during the 14 years of investigation and close to 40 interrogations were performed.

My lawyer, Ganden Tethong, has over 180 binders filled with court documents. In addition to this, I underwent two forensic psychological evaluations.

To top it off, my wife was accused of having violated Swiss bank secrecy – a tactic I believe was carried out to make sure she was not allowed to visit me during my time in solitary confinement.

I had to review 8 million computer files under the supervision of a police officer within three months in order to find evidence to justify my actions. The stress caused by the cases against me sent me to the hospital for three months, where I recovered but then was forced on December 10, 2014 (incidentally, World Human Rights Day) to attend a court trial where I had a second serious collapse within two days and was hospitalised again.

This has had a toll on my eleven year old daughter, who attempted to commit suicide, but was able to be rescued by a bunch of brilliant doctors. Family photographs, her computers, her play-machine her first story writings and other parts of her belongings are still confiscated by Swiss authorities.

In short, astronomical effort bordering on psychological warfare has been performed in order to make the scapegoat for the difficult times that Swiss bank secrecy has been exposed to in the last few years.

The Swiss media has not been helpful to say in the least. Various publications have called me a thief, a blackmailer, a psychologically sick person, a terrorist, neo-Nazi and caused irreversible reputational damage. One newspaper, Die Weltwoche a right-wing magazine, was later found guilty in three court trials of violating my personal rights.

However, as a former Swiss army captain of the Air Force, one knows the methodology by which people are mentally destroyed. One also knows how to defend oneself in such circumstances.

“Causa Elmer”, therefore, has turned into a “Causa Swiss bank secrecy”.

This was clear to me from when a well-known Geneva-based banker stated in 2007 to Professor Jean Ziegler that Julius Baer should make Elmer an offer of hush money of CHF 10 million or so to be silenced and to agree to close the pending legal case which threatens the entire Swiss banking industry as a whole.

The filing of the complaint by Bank Julius Baer & Co. AG, Zurich was a big management mistake. This case should have been solved with a cordial or gentlemen agreement which was common in Switzerland in those days.

On October 10, 2018, the five judges of the Federal Court of Switzerland will present their view and their rulings based on the governing law of Switzerland which currently requests a Swiss banker to be under Swiss bank secrecy law if he/she holds an employment contract with a bank that is domiciled in Switzerland and holds a Swiss banking license.

Julius Baer Bank & Trust Company Ltd., Cayman Islands is neither domiciled in Switzerland and does not have a Swiss banking licence. During the time of my employment, from 1994 to 2002, I held a Cayman employment contract with the sister entity of Julius Baer Bank & Co. AG, Zurich and had no reporting requirements to fulfill to the Swiss bank at all.

Therefore, according to leading Swiss legal experts, Swiss bank secrecy cannot be applied in my case.

The agreement with Bank Julius Baer & Co. AG, Zurich in respect of pension matters is by far not a Swiss employment contract because most of the key elements of an employment contract are missing. Besides this, for the very same time period, there was the true Cayman employment contract applicable. It appears that the true employment contracts were kept deliberately as long as possible out of the court files.

Only when two well-known legal professors, Mark Piet and Thomas Geiser, gave a second opinion to the courts, the judges of the Higher Court of Zurich were mostly forced to issue an acquittal in my case for charges related to violation of Swiss bank secrecy laws.

What is at stake?

The present causa of Swiss bank secrecy must be keeping the Swiss banking industry’s biggest clients on their toes.

Why? Because ultra high networth individuals all over the world and even multinational conglomerates, who use special purpose vehicles administered by Swiss banks holding a Swiss bank account, will be very keen on knowing the outcome of the Federal Court ruling.

Here are the questions at stake:

First, is it a fact that Swiss bank secrecy ends at the boundary of Switzerland?

Second, what happens to a client’s offshore structure (trusts, companies etc.) if it holds a Swiss bank account? Or put another way, how is it protected outside Switzerland?

Third, it is known that Swiss banks have outsourced accounting administration to so called low-costs countries such as Poland and therefore the question is how and under which law is my data protected if it is outside Switzerland in a so-called out-sourcing centre?

Fourth, in confirming the partial acquittal granted to me by the high court in 2016, with regard to violating Swiss bank secrecy, could this allow future and potential whistleblowers to come forward and make even more offshore data public?

Considering all of this, the Federal Court of Switzerland one or the other way will come up with an important verdict not only for me but for the future of Swiss Bank secrecy and the Swiss Banking industry.

The entire case is one for the history books, dealing as it does with one of the world’s best known secrecy laws. The outcome of the court ruling could also cause big change in the Swiss Banking industry as it puts a spotlight on questions that very few people in Switzerland’s financial industry have raised or want answered.

Thursday, 21 January 2016

The hidden wealth of nations

G Sampath in The Hindu

The Hindu

Tax havens such as Mauritius thrive parasitically, feeding on substantive economies like India.India’s biggest source of FDI is India itself, money departing on a short holiday to a tax haven and then routed back as FDI. Will the government muster up the political will to clamp down on the tax-allergic business elite?

This could be a bumper year for the ever-lucrative tax avoidance industry. The 2015 final reports of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)-led project on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) — which refer to the erosion of a nation’s tax base due to the accounting tricks of Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) and the legal but abusive shifting out of profits to low-tax jurisdictions respectively — lays out 15 action points to curb abusive tax avoidance by MNEs. As a participant of this project, India is expected to implement at least some of these measures. But can it? More pertinently, does it have the political will?

The BEPS project is no doubt a positive development for tax justice. If India’s recent economic history tells us anything, it is that economic growth without public investment in social infrastructure such as health care and education can do very little to better the life conditions of the majority. Which is why curbing tax evasion to boost public finance is part of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

However, notwithstanding the BEPS project, MNEs and their dedicated army of highly paid accountants are not about to roll over and comply. Again, if past history is any indication, the cat-and-mouse game between accountants and taxmen will continue, with new loopholes being unearthed in new tax rules.

Empowering tax dodgers

The primary cause of concern here is the quality of India’s political leadership, which has consistently betrayed its own taxmen. All it takes — regardless of the party in power — is for the stock market to sneeze, and the Indian state swoons. We’ve seen it happen time and again: the postponement of the enforcement of General Anti-Avoidance Rules (GAAR) to 2017, and more spectacularly, on the issue of participatory notes, or P-notes.

The primary cause of concern here is the quality of India’s political leadership, which has consistently betrayed its own taxmen. All it takes — regardless of the party in power — is for the stock market to sneeze, and the Indian state swoons. We’ve seen it happen time and again: the postponement of the enforcement of General Anti-Avoidance Rules (GAAR) to 2017, and more spectacularly, on the issue of participatory notes, or P-notes.

Last year, the Special Investigation Team (SIT) on black money had recommended mandatory disclosure to the regulator, as per Know Your Customer (KYC) norms, of the identity of the final owner of P-notes. It was a sane suggestion because the bulk of P-note investments in the Indian stock market were from tax havens such as Cayman Islands. But the markets threw a fit, with the Sensex crashing by 500 points in a day. The National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government, which had come to power promising to fight black money, promptly issued a statement assuring investors that it was in no hurry to implement the SIT recommendations. Given such a patchy record, what are the realistic chances of India actually clamping down on tax dodging?

Let’s take, for instance, Action No. 6 of the OECD’s BEPS report: it urges nations to curb treaty abuse by amending their Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements (DTAA) suitably. The obvious litmus test of India’s seriousness on BEPS is its DTAA with Mauritius. By way of background, Mauritius accounted for 34 per cent of India’s FDI equity inflows from 2000 to 2015. It’s been India’s single-largest source of FDI for nearly 15 years. Now, is it possible that there are so many rich businessmen in this tiny island nation with a population of just 1.2 million, all with a touching faith in India as an investment destination? If not, how do we explain an island economy with a GDP less than one-hundredth of India’s GDP supplying more than one-third of India’s FDI?

We all know the answer: Mauritius is a tax haven. While not in the same league as Cayman Islands or Bermuda, Mauritius is a rising star, thanks in no small measure to India’s patriotic but tragically tax-allergic business elite. In Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men Who Stole the World, financial journalist Nicholas Shaxson notes how Mauritius is a popular hub for what is known as “round-tripping”. He writes, “A wealthy Indian, say, will send his money to Mauritius, where it is dressed up in a secrecy structure, then disguised as foreign investment, before being returned to India. The sender of the money can avoid Indian tax on local earnings.”

In other words, it appears that India’s biggest source of FDI is India itself. Indian money departs on a short holiday to Mauritius, before returning home as FDI. Perhaps not all the FDI streaming in from Mauritius is round-tripped capital — maybe a part of it is ‘genuine’ FDI originating in Europe or the U.S. But it still denotes a massive loss of tax revenue, part of the $1.2 trillion stolen from developing countries every year.

What makes this theft of tax revenue not just possible but also legal is India’s DTAA with Mauritius. It’s a textbook example of ‘treaty shopping’ — a government-sponsored loophole for MNEs to avoid tax by channelling investments and profits through an offshore jurisdiction.

For instance, as per this DTAA, capital gains are taxable only in Mauritius, not in India. But here’s the thing: Mauritius does not tax capital gains. India, like any sensible country, does. What would any sensible businessman do? Set up a company in Mauritius, and route all Indian investments through it.

India signed this DTAA with Mauritius in 1983, but apparently ‘woke up’ only in 2000. India has spent much of 2015 ‘trying’ to renegotiate this treaty. But with our Indian-made foreign investors lobbying furiously, the talks have so far yielded nothing. Meanwhile, China, which too had the same problem with Mauritius, has already renegotiated its DTAA, and it can force investors to pay 10 per cent capital gains tax in China.

Changing profile of tax havens

Tax havens such as Mauritius thrive parasitically, feeding on substantive economies like India. Back in 2000, the OECD had identified 41 jurisdictions as tax havens. Today, as it humbly seeks their cooperation to combat tax avoidance, it calls them by a different name, so as not to offend them.

Tax havens such as Mauritius thrive parasitically, feeding on substantive economies like India. Back in 2000, the OECD had identified 41 jurisdictions as tax havens. Today, as it humbly seeks their cooperation to combat tax avoidance, it calls them by a different name, so as not to offend them.

The same list is now called — and this is not a joke — ‘Jurisdictions Committed to Improving Transparency and Establishing Effective Exchange of Information in Tax Matters’. Distinguished members of this club include Cayman Islands, Bermuda, Bahamas, Cyprus, and of course, Mauritius.

Today the function of tax havens in the global economy has evolved way beyond that of offering a low-tax jurisdiction. Mr. Shaxson describes three major elements that make tax havens tick. First, tax havens are not necessarily about geography; they are simply someplace else — a place where a country’s normal tax rules don’t apply. So, for instance, country A can serve as a tax haven for residents of country B, and vice versa. The U.S. is a classic example. It has stringent tax laws, and is energetic in prosecuting tax evasion by its citizens around the world. But it is equally keen to attract tax-evading capital from other countries, and does so through generous sops and helpful pieces of legislation which have effectively turned the U.S. into a tax haven for non-residents.

Second, more than the nominally low taxes, the bigger attraction of tax havens is secrecy. Secrecy is important for two reasons: to be able to avoid tax, you need to hide your real income; and to hide your real income, you need to hide your identity, so that the booty stashed away in a tax haven cannot be traced back to you by the taxmen at home. So, even a country whose taxes are not too low can function as a tax haven by offering a combination of exemptions and iron-clad secrecy — which is the formula adopted by the likes of Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

Third, the extreme combination of low taxes and high secrecy brought about a new mutation of tax havens in the 1960s: they turned themselves into offshore financial centres (OFCs). The economist Ronen Palan defines OFCs as “markets in which financial operators are permitted to raise funds from non-residents and invest or lend the money to other non-residents free from most regulations and taxes”. It is estimated that OFCs are recipients of 30 per cent of the world’s FDI, and are, in turn, the source of a similar quantum of FDI.

Such being the case, all India needs to do to attract FDI is to become an OFC, or create an OFC on its territory — bring offshore onshore, so to speak. That’s precisely what the U.S. did — it set up International Banking Facilities (IBFs), “to offer deposit and loan services to foreign residents and institutions free of… reserve requirements”. Japan set up the Japanese Offshore Market (JOM). Singapore has the Asian Currency Market (ACU), Thailand has the Bangkok International Banking Facility (BIBF), Malaysia has an OFC in Labuan island, and other countries have similar facilities. OFCs, as Ronen Palan puts it, are less tax havens than regulatory havens, which means that financial capital can do here what it cannot do ‘onshore’. So every major hedge fund operates out of an OFC. Given the volume of unregulated financial transactions that OFCs host, it is no surprise that they were at the heart of the 2008 financial crisis.

Apart from accumulating illicit capital (in the tax haven role), channelling this capital back onshore dressed up as FDI (in investment hub role), and deploying it to engage in destructive financial speculation (in OFC role), these strongholds of finance capital also serve a political function: they undermine democracy by enabling financial capture of the political levers of democratic states.

It is well known that political parties in most democracies are amply funded by slush funds that would not have accumulated in the first place had taxes been paid. But today, not least in the Anglophone world, global finance’s capture of the state appears more like the norm.

A lone exception seems to be Iceland, which began the new year on a rousing note — by sentencing 26 corrupt bankers to a combined 74 years in jail. Meanwhile in India, we continue to parrot long discredited clichés about the need for more financial deregulation and a weird logic that mandates a smaller and more limited role for public finance.

Tuesday, 2 December 2014

Why doctors fail

Atul Gawande in the Guardian

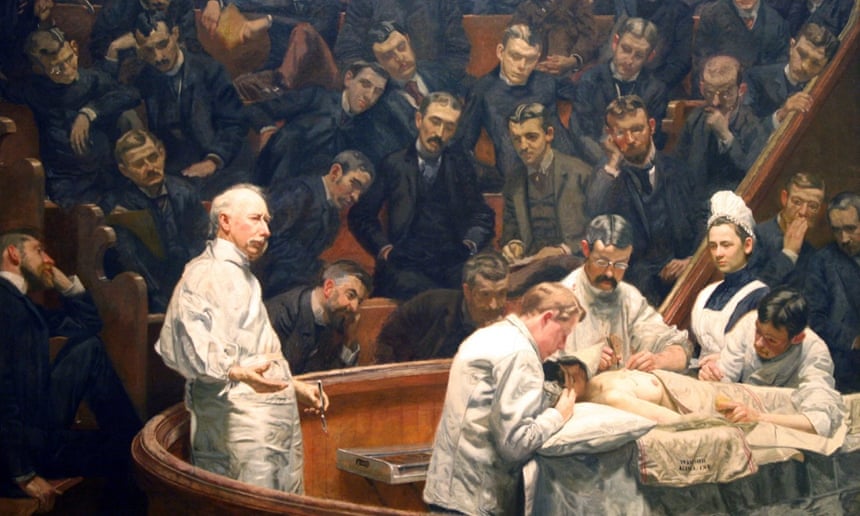

Doctors are fallible; of course they are. So why do they find this so hard to admit, and how can they work more openly? Atul Gawande lifts the veil of secrecy in the first of his Reith lectures

Millions of moments like this occur every day: a human being coming to another human being with the body or mind’s troubles and looking for assistance. That is the central act of medicine – that moment when one human being turns to another human being for help.

And it has always struck me how small and limited that moment is. We have 13 different organ systems and at the latest count we’ve identified more than 60,000 ways that they can go awry. The body is scarily intricate, unfathomable, hard to read. We are these hidden beings inside this fleshy sack of skin and we’ve spent thousands of years trying to understand what’s going on inside. To me, the story of medicine is the story of how we deal with the incompleteness of our knowledge and the fallibility of our skills.

There was an essay that I read two decades ago that I think has influenced almost every bit of writing and research I’ve done ever since. It was by two philosophers – Samuel Gorovitz and Alasdair MacIntyre – and their subject was the nature of human fallibility. They wondered why human beings fail at anything that we set out to do. Why, for example, would a meteorologist fail to correctly predict where a hurricane was going to make landfall, or why might a doctor fail to figure out what was going on inside my son and fix it? They argued that there are two primary reasons why we might fail. The first is ignorance: we have only a limited understanding of all of the relevant physical laws and conditions that apply to any given problem or circumstance. The second reason, however, they called “ineptitude”, meaning that the knowledge exists but an individual or a group of individuals fail to apply that knowledge correctly.

We’ve relied on science to overcome ignorance, and the course of that work has itself been fascinating. That visit we made in 1995 to our paediatrician and everything that she did to sort out what was happening in my son could be traced back to 1628 when the English physician William Harvey, after millennia of ignorance, finally worked out that the heart is a pump that moves blood in a circular course through the body.

Another critical step came three centuries later, in 1929, when Werner Forssmann, a surgical intern in Eberswalde, Germany, made an observation. Forssmann was reading an obscure medical journal when he noticed an article depicting a horse in which researchers had threaded a long tube up its leg all the way into its heart. They described, to his amazement, taking blood samples from inside a living heart without harm. And he said: “Well, if we could do that to a horse, what if we did that to a human being?” Forssmann went to his superiors and said: “How about we take a tube and thread it into a human being’s heart?”

Their response was, in essence, “You’re crazy. You can’t do that. Whenever anyone touches the heart in surgery, it goes into fibrillation and the patient dies.”

He said: “Well what about in an animal?”

And they said: “There’s no point and you’re just an intern anyway. Who says you should even deserve to get to ask these questions? Go back to work.”

But Forssmann just had to give it a try. So he stole into the x-ray room, took a urinary catheter, made a slit in his own arm, threaded it up his vein and into his own heart and convinced a nurse to help him take a series of nine x-rays showing the tube inside his own heart.

He published the evidence – and was fired. Then in 1956, he was awarded the Nobel prize in medicine with André Cournand and Dickinson Richards who, some 20 years later at Columbia University, had taken Forssmann’s findings and recognised that you could not only put a catheter into the human heart but also shoot dye through the catheter. That enabled them to take pictures and see from the inside how the heart actually worked. Together the three had founded the field of cardiology. After this, doctors began devising ways to fix what was found going wrong inside the heart.

Science is concerned with universal truths, laws of how the body or the world behaves. Application, however, is concerned with the particularities, and the test of the science is how the universalities apply to the particularities. Do the general ideas about the worrying sounds the paediatrician heard in my son’s chest correspond with the unique particularities of Walker? Here Gorovitz and MacIntyre saw a third possible kind of failure. Besides ignorance, besides ineptitude, they said that there is necessary fallibility, some knowledge science can never deliver on. They went back to the example of how a given hurricane will behave when it makes landfall, how fast it will be going when it does, and what they said is that we’re asking science to do more than it can when we ask it to tell us what exactly is going on. All hurricanes follow predictable laws of behaviour but no hurricane is like any other hurricane. Each one is unique. We cannot have perfect knowledge of a hurricane, short of having a complete understanding of all the laws that describe natural processes and a complete description of the world, they said. It required, in other words, omniscience, and we can’t have that.

The interesting question, then, is how do we cope? It’s not that it’s impossible to predict anything. Some things are completely predictable. Gorovitz and MacIntyre gave the example of a random ice cube in a fire. An ice cube is so simple and so similar to other ice cubes that you can have complete assurance that if you put it in the fire, it will melt. Our puzzle is: are human beings more like hurricanes or more like ice cubes?

Following the paediatrician’s instructions, we took Walker to the emergency room. It was a Sunday morning. A nurse took an oxygen monitor, one of those finger probes with the red light, and put it on the finger of his right hand. And the oxygen level was 98%, virtually perfect. They took a chest x-ray, and it showed that the lungs were both whited out. They read it. They said: “This is pneumonia.” They did a spinal tap to make sure that it wasn’t signs of infection that had spread from meningitis. They started him on antibiotics and they called the paediatrician to let her know the diagnosis they’d found. It wasn’t the heart, they said. It was the lungs. He had pneumonia. And she said: “No, that can’t be right.” She came into the emergency room and she took one look at him – he was having trouble breathing, he was not doing great – and she saw that the finger probe with the oxygen monitor was on the wrong finger.

It turns out there are certain conditions in which the aorta can be interrupted. You can be born with an incomplete aorta and so the blood flow can come out of the heart and go to the right side of the upper body, into the hand that had that probe, but it may not go to the left side of the upper body or anywhere else. And that turned out to be what was going on. She switched the probe over to the left hand and he had an unreadable oxygen level. He was in fact going into kidney and liver failure. He was in serious trouble. She had caught a failure to apply the knowledge science has to this particular situation.

Then the team made a prediction. In this circumstance, we do have a drug – only put into use, it turned out, about a decade before my son was born: prostaglandin E2, a little molecule that can reopen the foetal circulation. When you’re a foetus in the womb, you have a bypass system that sends a separate blood supply that can stay open for a couple of weeks after birth. This system had shut down and that’s why he went into failure. But this molecule can reopen that pathway and the prediction was that this child was like every other child – that you could know what had happened to other children and could apply it here and that it would open up that foetal circulation, this bypass system. And it did. That gave him time to recover in the intensive care unit, to let his kidney and his liver recover, to let his gut start working again, and then to undergo cardiac surgery to replace his malformed aorta and to fix the holes that were present in his heart as well. They saved him.

They saved him.

There are more and more ways in which we are as knowable as ice cubes. We understand with great precision how mothers can die in childbirth, how certain tumours behave, how the Ebola virus spreads, how the heart can go wrong and be fixed. Certainly, we have many, many areas of continuing ignorance – how to stop Alzheimer’s disease or metastatic cancers, how we might make a vaccine against this virus we’re dealing with now. But the story of our time, I think, is as much a story about struggling with ineptitude as struggling with ignorance.

You go back a hundred years or more, and we lived in a world where our futures were governed largely by ignorance. But over this last century, we’ve come through an extraordinary explosion of discovery. The puzzle has, therefore, become not only how we close the gaps of ignorance open to us, but also how we ensure that the knowledge gets through, that the finger probe is on the correct finger.

Next to my son, in the intensive care unit, there was a child from Maine, which is about 200 miles away, who had virtually the same diagnosis that Walker had. And when this boy was diagnosed, it took too long for the problem to be recognised, for transportation to be arranged, and for him to get that drug to give him back that open circulation. The result was that the poor child with the same condition my son had, in the very next bed to ours, gone into complete liver and kidney failure, and his only chance was to wait for an organ transplant and hope for a future that was going to be very different from the one my son was going to have.

And then I think back on my family. My parents come from India; my father from a rural village, my mother from a big city in the north. If Walker had been anything like my nieces and nephews in the village where my family still farms – they’re farmers growing wheat and sugarcane and cotton – and if he’d been there, there would have been no chance at all.

There’s a misconception about global health. We think global health is about care in just the poorest parts of the world. But the way I think about global health, it’s about making care better everywhere – the idea that we are trying to deploy the capabilities that we have discovered over the last century, town by town, to every person alive. We’ve had an extraordinary transformation around the world. Economically, even with the last recession, we’ve had the rising of global economies on every continent and the result has been a dramatic change in the length of lives all across the world. Respiratory illness and malnutrition used to be the biggest killers. Now it’s cardiovascular disease; road traffic accidents are a top five killer and cancers are in the top 10. With economic progress has come the broader knowledge for people that solutions exist.

My family members in our village in India know that solutions exist to the problems they have, and so the puzzle is how we deploy that capability everywhere – in India, in Maine, across the UK, Europe, Latin America, the world. We’re only just discovering the patterns of how we begin to do that.

In the course of this year’s Reith lectures, I’m going to attempt to unpack three ideas. First is what we’re learning from opening the door, from seeing behind the curtains of how medicine and public health are actually practised and discovering how much can be done better that saves lives and reduces suffering. Second is the reality of our necessary fallibility and how we cope effectively with the fact that our knowledge is always limited. Third, I will consider the implications of both of these – the implications of what we’re learning about our ineptitude and about our necessary fallibility – for the global future of medicine and health.

It is uncomfortable looking inside our fallibility. We have a fear of looking. We’re like the doctors who dug up bodies in the 19th century to dissect them, in order to know what was really happening inside. We’re looking inside our systems and how they really work. And like before, what we find is messier than we knew and sometimes messier than we might have wanted to know.

In some ways, turning on the cameras inside our world can be more treacherous. There’s a reason that Gorovitz and MacIntyre labelled the kind of failures we have “ineptitude”. There’s a sense that there’s some shame or guilt attached to the fact that we don’t get it right all the time. And exposing this reality can make people more angry than exposing the reality of how the body works. Therefore, we’ve blocked many of these efforts to try to provide some transparency to what’s going on. Audiotapes are often not allowed, the video recorders are turned off. We have no black box for what happens in our operating rooms or in our clinics. The data, when we have it, is often locked up. You can’t know, even though we have the information, which hospitals have a better complication rate in certain kinds of operations than others. There’s a fear of misuse, a fear of injustice in doing it, in exposing it.

Arguably, not opening up the doors puts lives at stake. What we find out can often be miraculous. By closing ourselves off, we’re missing important opportunities.

The doctors told us when Walker went home that he was going to need a second operation. The repair that he’d had was one that replaced a section of his aorta – the tube coming out of his heart to carry blood supply throughout the rest of the body – with an artificial tube when he was 11 days old. It was almost like a straw. Now they had designed it to expand a bit as he grew, but it was not going to accommodate an adult-sized body. So they told us that when he became a teenager he would have to get a new replacement aorta and that he would have to undergo a major operation. Being a surgery resident, I knew what that entailed. Repeat aortic surgery has up to a 5% chance of death and a 25% chance of paralysis. We lived in some fear about when that moment would come.

When that moment came, he was 14 years old, and the world had changed. By then technology had developed to allow his aorta to be expanded with a simple catheter. We found the expert who had learned, and even devised, some of the methods for being able to do that, in Boston. He explained to me, cardiologist to surgeon, just how it’s done and sometimes you learn stuff you don’t necessarily want to know. He talked about how he would have to apply pressure to a balloon that would be threaded up inside the aorta. I asked how he knew what pressure to apply. He said it was by feel. He could feel the vessel tearing, and the trick was to tear it just enough that it can expand but not so much that it ruptures.

There was a necessary fallibility in what he was attempting to do – some irreducible probability of failure. But Walker got through that procedure just fine. The extraordinary thing was the very next day he went home, and the day after that he was so well that he played sports and injured his ankle on the playing field. This June he graduated from high school and this autumn he started college. He’s going to live a long and normal life, and that is amazing. The key question we have to ask ourselves is how are we going to make it possible for others to have that, how do we fulfil our duty to make it possible for others? The only way I can see is by removing the veil around what happens in that procedure room, in that clinic, in that office or that hospital. Only by making what has been invisible visible. This is why I write, this is why we do the science we do – because this is how we understand – and that is the key to the future of medicine.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)