'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label white. Show all posts

Showing posts with label white. Show all posts

Wednesday, 13 July 2022

Sunday, 3 July 2022

Saturday, 16 April 2022

Monday, 14 February 2022

English football: why are there so few black people in senior positions?

Simon Kuper in The FT

Possibly the only English football club run mostly by black staff is Queens Park Rangers, in the Championship, the English game’s second tier.

QPR’s director of football, Les Ferdinand, and technical director, Chris Ramsey, have spent their entire careers in the sport watching hiring discrimination persist almost everywhere else. Teams have knelt in protest against racism, but Ferdinand says, “I didn’t want to see people taking the knee. I just wanted to see action. I’m tired of all these gestures.”

Now a newly founded group, the Black Footballers Partnership (BFP), argues that it is time to adopt compulsory hiring quotas for minorities. Voluntary measures have not worked, says its executive director, Delroy Corinaldi.

The BFP has commissioned a report from Stefan Szymanski (economics professor at the University of Michigan, and my co-author on the book Soccernomics) to document apparent discrimination in coaching, executive and scouting jobs.

It is a dogma of football that these roles must be filled by ex-players — but only, it seems, by white ones. Last year 43 per cent of players in the Premier League were black, yet black people held “only 4.4 per cent of managerial positions, usually taken by former players” and 1.6 per cent of “executive, leadership and ownership positions”, writes Szymanski.

Today 14 per cent of holders of the highest coaching badge in England, the Uefa Pro Licence, are black, but they too confront prejudice. Looking ahead, the paucity of black scouts and junior coaches is keeping the pipeline for bigger jobs overwhelmingly white. Corinaldi hopes that current black footballers will follow England’s forward Raheem Sterling in calling for more off-field representation.

There have been 28 black managers in the English game since the Football League was founded in 1888, calculates Corinaldi. As for the Premier League, which has had 11 black managers in 30 years, he says: “Sam Allardyce [an ex-England manager] has had nearly as many roles as the whole black population.” The situation is similar in women’s football, says former England international Anita Asante.

Ramsey, who entered coaching in the late 1980s, when he says “there were literally no black coaches”, reflects: “There’s always a dream that you’re going to make the highest level, so naively you coach believing that your talent will get you there, but very early on I realised that wasn’t going to happen.”

Reluctant to hire

He says discrimination in hiring is always unspoken: “People hide behind politically correct language. They will take a knee, and say, ‘I’m all for it’. You’re just never really seen as able to do the job. And then people sometimes employ people less qualified than you. Plenty of white managers have failed, and I just want to have the opportunity to be as bad as them, and to be given an opportunity again. You don’t want to have to be better just because you’re black.”

When Ferdinand’s glittering playing career ended, he worried that studying for his coaching badges might “waste five years of my life”, given that the white men running clubs were reluctant to hire even famous black ex-players such as John Barnes and Paul Ince. In Ferdinand’s first seven years on the market, he was offered one managerial job. “People tend to employ what looks, sounds and acts like them,” he shrugs. Yet he says he isn’t angry: “Anger’s not the right word, because that’s unfortunately how they see a lot of young black men, as angry.”

He suspects QPR hired him in part because its then co-chair, the Malaysian Tony Fernandes, is a person of colour. After the two men met and began talking, recalls Ferdinand, “he said, ‘Why are you not doing this job [management] in football?’ I said, ‘Because I’ve not been given the opportunity.’ The conversations went from there. Had he not been a person of colour, I perhaps wouldn’t have had the opportunity to talk to him in the way that I did.”

Szymanski can identify only two black owners in English football, both at small clubs: Ben Robinson of Burton Albion, and Ryan Giggs, co-owner of Salford City.

Szymanski believes discrimination persists for managerial jobs in part because football managers have little impact on team performance — much less than is commonly thought. He calculates that over 10 seasons, the average correlation between a club’s wage bill for players and its league position exceeds 90 per cent. If the quality of players determines results almost by itself, then managers are relatively insignificant, and so clubs can continue to hire the stereotype manager — a white male ex-player aged between 35 and 55 — without harming their on-field performance.

For about 20 years, English football has launched various fruitless attempts to address discrimination. Ramsey recalls the Football Association — the national governing body — inviting black ex-players to “observe” training sessions. He marvels: “You’re talking about qualified people with full badges standing and watching people train. And most of them have been in the game longer than the people they’re watching.”

Modest though that initiative was, Ferdinand recalls warning FA officials: “A certain amount of people at St George’s Park [the FA’s National Football Centre], when you tell them this is the initiative, their eyes will be rolling and thinking, ‘Here we go, we’re doing something for them again, we’re trying to give them another opportunity.’ What those people don’t realise is: we don’t get opportunities.”

Rooney Rule

After the NFL of American gridiron football introduced the Rooney Rule in 2003, requiring teams to interview minority candidates for job openings, the English ex-player Ricky Hill presented the idea to the League Managers Association. Ramsey recalls, “Everyone said, ‘God, this is brilliant’.” Yet only in the 2016/2017 season did 10 smaller English clubs even pilot the Rooney Rule. Ramsey says: “We are expected to accept as minority coaches that these things take a long time. I have seen this train move along so slowly that it’s ridiculous.” He mourns the black managerial careers lost in the wait.

In 2019 the Rooney Rule was made mandatory in the three lower tiers of English professional football, though not in the Premier League or anywhere else in Europe. Clubs had to interview at least one black, Asian or minority ethnic (Bame) candidate (if any applied) for all first team managerial, coaching and youth development roles. Why didn’t the rule noticeably increase minority hiring? Ferdinand replies, “Because there’s nobody being held accountable to it. What is the Rooney Rule? You give someone the opportunity to come through the door and talk.” Moreover, English football’s version of the rule has a significant loophole: clubs are exempt if they interview only one candidate, typically someone found through the white old boys’ network.

Nor has the Rooney Rule made much difference in the NFL. In 2020, 57.5 per cent of the league’s players were black, but today only two out of 32 head coaches are, while one other identifies as multiracial. This month, the former Miami Dolphins coach Brian Flores filed a lawsuit against the NFL and three clubs, accusing them of racist and discriminatory practices. He and other black coaches report being called for sham interviews for jobs that have already been filled, as teams tick the Rooney Rule’s boxes.

Voluntary diversity targets

In 2020 England’s FA adopted a voluntary “Football Leadership Diversity Code”. Only about half of English professional clubs signed it. They committed to achieving percentage targets for Bame people among new hires: 15 per cent for senior leadership and team operations positions, and 25 per cent for men’s coaching — “a discrepancy in goals that itself reflects the problem”, comments Szymanski. Clubs were further allowed to water down these targets “based on local demographics”.

The FA said: “The FA is deeply committed to ensuring the diversity of those playing and coaching within English football is truly reflective of our modern society.

“We’re focused on increasing the number of, and ongoing support for, coaches who have been historically under-represented in the game. This includes a bursary programme for the Uefa qualifications required to coach in academy and senior professional football.”

A report last November showed mixed results. Many clubs had missed the code’s targets, with several Premier League clubs reporting zero diversity hires. On the other hand, more than 20 per cent of new hires in men’s football were of Bame origin, which was at least well above historical hiring rates.

Do clubs take the code seriously? Ferdinand smiles ironically: “From day one I didn’t take it seriously. Because it’s a voluntary code. What’s the repercussions if you don’t follow the voluntary code? No one will say anything, no one will do anything about it.”

The BFP and the League Managers Association have called for the code’s targets to be made compulsory. Ferdinand cites the example of countries that set mandatory quotas for women on corporate boards of listed companies.

Asante says it takes minorities in positions of power to understand the problems of minorities. “If you are a majority in any group, when are you ever thinking about the needs of others?” Corinaldi adds: “When you have a monoculture in any boardroom, you only know what you know, and it tends to be the same stories you heard growing up.” He predicts that once football has more black directors and senior executives, they will hire more diversely.

The BFP’s model for English football is the National Basketball Association in the US, a 30-team league with 14 African-American head coaches. For now, that feels like a distant utopia. Ramsey warns: “If there is no revolutionary action, we’ll be having this same conversation in 10 years’ time.” And he remembers saying exactly those words 10 years ago.

Monday, 28 June 2021

Monday, 8 March 2021

Saturday, 4 July 2020

We can't talk about racism without understanding whiteness

To dismantle racial hierarchy, we need to start by discussing the power it grants those on top writes Priyamvada Gopal in The Guardian

One of my less discourteous correspondents last week asked me, using only one expletive, why people “need a manual for race relations” when we could just respect each other. Unfortunately, until we get to a point where all lives really do matter, there is no point in declaring that race doesn’t make a difference or that equality exists, when it clearly doesn’t. “White lives matter” implicitly suggests whites matter more than others. “Black lives matter” is saying those lives need to matter more than they have, that society needs to give them more weight. Until we square up to the ugly realities of how whiteness operates – lethally, invisibly, powerfully – we are doomed to fighting a toxic and pointless culture war, where the only winners are those who want hatred to prevail.

Manchester City and Burnley players - and the referee, Andre Marriner - take a knee before their match at the Etihad Stadium last month. Photograph: Michael Regan/NMC/EPA

When it comes to race and racism, we focus on those at the sharp end of discrimination – from black people routinely subjected to police brutality to people of colour missing from positions of influence. Progressive ideals invoke “inclusion” for ethnic minorities, or special bias training. These measures may be necessary, but they put the focus squarely on those subjected to victimisation – rather than the system that perpetuates racism.

What results is a form of benevolence whereby some people of colour get “included” as part of diversity measures, even as social hierarchies and habits of thought in white-majority societies remain largely unchanged.

There is no point in declaring that race doesn’t make a difference or that equality exists when it clearly doesn’t

The truth is that there is nothing pleasant about confronting the reality of an acute racial hierarchy. If the racial order is really to change – and there are those who don’t want it to – it is not just black lives or racial minorities that should be the topic of discussion, but the racial ideology that currently calls the shots in western societies.

This is what brings us to “whiteness” – which is not a biological category so much as a set of ideas and practices about race that has emerged from a bedrock of white supremacy, itself the legacy of empire and slavery. Confronting the idea of whiteness involves far more uncomfortable discussions than “inclusion”, especially for people deemed white, since it involves self-examination and acknowledging ugly truths, both historical and contemporary. It is simply easier to try to shut it out or down.

I found this out to my cost last week when I tweeted a response to the racially inflammatory “White Lives Matter” banner flown over the Etihad Stadium after Manchester City and Burnley footballers had “taken the knee” to honour George Floyd. My tweet, deliberately playing with the wording of the banner by qualifying it, made the point that white lives cannot be deemed to matter because they are white, that it should not be whiteness that gives those lives value. In addition to the tsunami of racist sewage that immediately came my way, littered with N-words and P-words along with sexist slurs, rape fantasies, death threats and open declarations that “white lives matter more”, I was repeatedly asked why, if white lives did not matter as white lives, do black lives matter? Was that also not also racist?

No, it is not also racist. White lives already matter more than others so to keep proclaiming they matter is to add excess value to them, tilting us dangerously into white supremacy. This doesn’t mean that all white people in western societies are materially well-off or don’t experience hardship, but that they don’t do so by virtue of the fact that they are white. Black lives remain undervalued and in order for us to get to the desirable point where all lives (really do) matter, they must first achieve parity by mattering. It’s not really that hard to understand unless you choose not to.

Studies of “whiteness” are not new. Respected scholars, such as the late Noel Ignatiev, author of How the Irish Became White, and David Roediger, have studied the history and sociology of whiteness in great detail. Ignatiev, who was Jewish, wrote about the “abolition of whiteness”, not as a call to eliminate white people but a system of racial entitlement that necessarily relied on the exclusion of those deemed to be lesser. For Ignatiev, whiteness was not a biological fact so much as a kind of ideological club where “the members go through life accepting the benefits of membership, without thinking about the cost” to others.

Over time, people have been added to the club and aspire to membership of it, from the Irish and European Jews to many Asians today. One distinctive feature of whiteness as ideology is that it can make itself invisible and thereby make its operations more lethal and harder to challenge. Science and the humanities are largely in accord that “race” is not a biological category, but a way of creating power differentials, which have practical consequences. If that power differential in western societies is to be removed, then the ideology at the top – whiteness – must be abolished. Only then can the abolition of all other racial categories – and the post-racial world we so often claim to espouse – actually follow.

Although in Britain I am racialised as “non-white” or Asian, in my birth country of India I have some experience of what it is like to be a member of a powerful but invisible ruling category. As a Brahmin (the “highest-ranking” tier of the deeply hierarchical Hindu caste system), I belong to a social grouping that operates much like whiteness does. It rules the roost, is not disadvantaged by virtue of caste (though there are those who might suffer from poverty or misogyny), and it treats any challenge to its power as a form of victimisation or “reverse oppression”. For the record, there is no such thing: oppression only operates downwards. This is why, at the same time as I reinforced Ignatiev’s call for the abolition of “whiteness”, I repeated that Brahmin supremacy in India must also be abolished.

When it comes to race and racism, we focus on those at the sharp end of discrimination – from black people routinely subjected to police brutality to people of colour missing from positions of influence. Progressive ideals invoke “inclusion” for ethnic minorities, or special bias training. These measures may be necessary, but they put the focus squarely on those subjected to victimisation – rather than the system that perpetuates racism.

What results is a form of benevolence whereby some people of colour get “included” as part of diversity measures, even as social hierarchies and habits of thought in white-majority societies remain largely unchanged.

There is no point in declaring that race doesn’t make a difference or that equality exists when it clearly doesn’t

The truth is that there is nothing pleasant about confronting the reality of an acute racial hierarchy. If the racial order is really to change – and there are those who don’t want it to – it is not just black lives or racial minorities that should be the topic of discussion, but the racial ideology that currently calls the shots in western societies.

This is what brings us to “whiteness” – which is not a biological category so much as a set of ideas and practices about race that has emerged from a bedrock of white supremacy, itself the legacy of empire and slavery. Confronting the idea of whiteness involves far more uncomfortable discussions than “inclusion”, especially for people deemed white, since it involves self-examination and acknowledging ugly truths, both historical and contemporary. It is simply easier to try to shut it out or down.

I found this out to my cost last week when I tweeted a response to the racially inflammatory “White Lives Matter” banner flown over the Etihad Stadium after Manchester City and Burnley footballers had “taken the knee” to honour George Floyd. My tweet, deliberately playing with the wording of the banner by qualifying it, made the point that white lives cannot be deemed to matter because they are white, that it should not be whiteness that gives those lives value. In addition to the tsunami of racist sewage that immediately came my way, littered with N-words and P-words along with sexist slurs, rape fantasies, death threats and open declarations that “white lives matter more”, I was repeatedly asked why, if white lives did not matter as white lives, do black lives matter? Was that also not also racist?

No, it is not also racist. White lives already matter more than others so to keep proclaiming they matter is to add excess value to them, tilting us dangerously into white supremacy. This doesn’t mean that all white people in western societies are materially well-off or don’t experience hardship, but that they don’t do so by virtue of the fact that they are white. Black lives remain undervalued and in order for us to get to the desirable point where all lives (really do) matter, they must first achieve parity by mattering. It’s not really that hard to understand unless you choose not to.

Studies of “whiteness” are not new. Respected scholars, such as the late Noel Ignatiev, author of How the Irish Became White, and David Roediger, have studied the history and sociology of whiteness in great detail. Ignatiev, who was Jewish, wrote about the “abolition of whiteness”, not as a call to eliminate white people but a system of racial entitlement that necessarily relied on the exclusion of those deemed to be lesser. For Ignatiev, whiteness was not a biological fact so much as a kind of ideological club where “the members go through life accepting the benefits of membership, without thinking about the cost” to others.

Over time, people have been added to the club and aspire to membership of it, from the Irish and European Jews to many Asians today. One distinctive feature of whiteness as ideology is that it can make itself invisible and thereby make its operations more lethal and harder to challenge. Science and the humanities are largely in accord that “race” is not a biological category, but a way of creating power differentials, which have practical consequences. If that power differential in western societies is to be removed, then the ideology at the top – whiteness – must be abolished. Only then can the abolition of all other racial categories – and the post-racial world we so often claim to espouse – actually follow.

Although in Britain I am racialised as “non-white” or Asian, in my birth country of India I have some experience of what it is like to be a member of a powerful but invisible ruling category. As a Brahmin (the “highest-ranking” tier of the deeply hierarchical Hindu caste system), I belong to a social grouping that operates much like whiteness does. It rules the roost, is not disadvantaged by virtue of caste (though there are those who might suffer from poverty or misogyny), and it treats any challenge to its power as a form of victimisation or “reverse oppression”. For the record, there is no such thing: oppression only operates downwards. This is why, at the same time as I reinforced Ignatiev’s call for the abolition of “whiteness”, I repeated that Brahmin supremacy in India must also be abolished.

One of my less discourteous correspondents last week asked me, using only one expletive, why people “need a manual for race relations” when we could just respect each other. Unfortunately, until we get to a point where all lives really do matter, there is no point in declaring that race doesn’t make a difference or that equality exists, when it clearly doesn’t. “White lives matter” implicitly suggests whites matter more than others. “Black lives matter” is saying those lives need to matter more than they have, that society needs to give them more weight. Until we square up to the ugly realities of how whiteness operates – lethally, invisibly, powerfully – we are doomed to fighting a toxic and pointless culture war, where the only winners are those who want hatred to prevail.

Thursday, 11 June 2020

It's time we South Asians understood that colourism is racism

What should we feel, and I ask my fellow South Asians this, having heard Daren Sammy raise the issue of being called kalu by his IPL team-mates? Horror and shame?

It is easy to imagine the befuddlement among some of his former team-mates. That was racist? Weren't - and aren't - we all buddies? Wasn't someone called a motu and someone else a lambu? What about all the camaraderie, and where was the offence when we were all having a jolly time?

How horrified and ashamed are we, really? Have we not thought, even in passing, that this could be a case of dressing-room banter being conflated with racism? And can we, hand on heart, say that we are completely surprised the things Sammy says happened did happen?

Once we have played all these questions in our minds, only one remains: how do we not know that this is so horribly wrong? It's not about whether Sammy knew the meaning of the word; it's about what his team-mates didn't know.

To address this, we must first widen the scope beyond Sammy and Sunrisers Hyderabad. We are at an extraordinary moment in history where a black man being publicly choked to death by a figure of authority has not only sparked worldwide mass outrage, but has also created a heightened sense of awareness about discrimination on the basis of colour, and led to the re-examination of a wide range of social behaviours.

To find the explanation for how it became okay for a group of international cricketers to address - in terms of endearment, they may add - a black West Indian player as kalu, we must face one of the most insidious practices in South Asian culture: colourism.

The elevation of whiteness is not a subcontinental phenomenon. The idea has been seeded over centuries, through religion, cultural imagery, and most profoundly, language, that "white" connotes everything pristine, pure and fair (consider the word "fair" itself) and that "dark" represents everything sinister. Watch Muhammad Ali take this on with cutting simplicity here.

But to understand how this idea originated and grew in the subcontinent, which suffered over 200 years of colonial subjugation and still suffers caste-based discrimination, one must sift through complex layers of sociocultural conditioning based on the regressive dynamics of class, caste, sect and gender. The hierarchy of skin colour is all pervasive in the region, and it doesn't strike most as odd, much less repugnant, that lightness of complexion should be so deeply linked to ideas of beauty.

This idea has been reinforced over decades through popular culture. You need to look no further than mainstream cinema in India: how many of our successful actors, especially women, are representative of the median South Asian skin tone? In the matrimonial pages, fair skin is peddled as a clinching eligibility factor, and consequently, ads for fairness creams position them as agents of salvation and success. So organically is this drilled into the mass subconscious that the obsession has ceased to be offensive: it is merely aspirational.

Add to this another subcontinental abomination - the practice of addressing people by their physical attributes - and you have a recipe for something utterly toxic. These terms of address are demeaning but normalised by a coating of endearment: jaadya or motu for the heavy-set, chhotu or batka for the short, kana for those who squint, and quite seamlessly, kalu or kaliya for those with skin tones darker than that of the majority.

This would perhaps explain Sarfaraz Ahmed's mild bemusement at the outrage over his "Abey kaale" remark to Andile Phehlukwayo in Durban last year. Ahmed, then Pakistan's captain, was speaking in Urdu, so it was apparent that he didn't expect Phehlukwayo, the South Africa allrounder, to understand the sledge, and that anyone familiar with the culture in Pakistan would have understood that he did not intend it as a racial slur.

But it can't be emphasised more that racist utterances are no longer about intent, because intent is so organically and inextricably loaded into the words themselves that it is no longer acceptable to explain them away with "It was not intended to be racist, or to cause hurt or offence." It's for all of us to internalise, more so for public figures: offence not meant is not equal to offence not given or received.

It is easy to imagine the befuddlement among some of his former team-mates. That was racist? Weren't - and aren't - we all buddies? Wasn't someone called a motu and someone else a lambu? What about all the camaraderie, and where was the offence when we were all having a jolly time?

How horrified and ashamed are we, really? Have we not thought, even in passing, that this could be a case of dressing-room banter being conflated with racism? And can we, hand on heart, say that we are completely surprised the things Sammy says happened did happen?

Once we have played all these questions in our minds, only one remains: how do we not know that this is so horribly wrong? It's not about whether Sammy knew the meaning of the word; it's about what his team-mates didn't know.

To address this, we must first widen the scope beyond Sammy and Sunrisers Hyderabad. We are at an extraordinary moment in history where a black man being publicly choked to death by a figure of authority has not only sparked worldwide mass outrage, but has also created a heightened sense of awareness about discrimination on the basis of colour, and led to the re-examination of a wide range of social behaviours.

To find the explanation for how it became okay for a group of international cricketers to address - in terms of endearment, they may add - a black West Indian player as kalu, we must face one of the most insidious practices in South Asian culture: colourism.

The elevation of whiteness is not a subcontinental phenomenon. The idea has been seeded over centuries, through religion, cultural imagery, and most profoundly, language, that "white" connotes everything pristine, pure and fair (consider the word "fair" itself) and that "dark" represents everything sinister. Watch Muhammad Ali take this on with cutting simplicity here.

But to understand how this idea originated and grew in the subcontinent, which suffered over 200 years of colonial subjugation and still suffers caste-based discrimination, one must sift through complex layers of sociocultural conditioning based on the regressive dynamics of class, caste, sect and gender. The hierarchy of skin colour is all pervasive in the region, and it doesn't strike most as odd, much less repugnant, that lightness of complexion should be so deeply linked to ideas of beauty.

This idea has been reinforced over decades through popular culture. You need to look no further than mainstream cinema in India: how many of our successful actors, especially women, are representative of the median South Asian skin tone? In the matrimonial pages, fair skin is peddled as a clinching eligibility factor, and consequently, ads for fairness creams position them as agents of salvation and success. So organically is this drilled into the mass subconscious that the obsession has ceased to be offensive: it is merely aspirational.

Add to this another subcontinental abomination - the practice of addressing people by their physical attributes - and you have a recipe for something utterly toxic. These terms of address are demeaning but normalised by a coating of endearment: jaadya or motu for the heavy-set, chhotu or batka for the short, kana for those who squint, and quite seamlessly, kalu or kaliya for those with skin tones darker than that of the majority.

This would perhaps explain Sarfaraz Ahmed's mild bemusement at the outrage over his "Abey kaale" remark to Andile Phehlukwayo in Durban last year. Ahmed, then Pakistan's captain, was speaking in Urdu, so it was apparent that he didn't expect Phehlukwayo, the South Africa allrounder, to understand the sledge, and that anyone familiar with the culture in Pakistan would have understood that he did not intend it as a racial slur.

But it can't be emphasised more that racist utterances are no longer about intent, because intent is so organically and inextricably loaded into the words themselves that it is no longer acceptable to explain them away with "It was not intended to be racist, or to cause hurt or offence." It's for all of us to internalise, more so for public figures: offence not meant is not equal to offence not given or received.

The silence of victims mustn't be misread. It does not mean willing acceptance. In most cases, they have no choice. They often find themselves outnumbered in social groups - or in dressing rooms - and choose to belong, rather than to confront. Former India opening batsman Abhinav Mukund brought this to light a few years ago with a poignant post on Twitter about how he had to "toughen up" against "people's constant obsession" with his skin colour. In a dressing-room scenario, where the eagerness to conform is far more acute, and where a culture of bullying isn't alien, the compulsion to grin and bear these "friendly" jibes is even more severe.

It doesn't have to be. It might take years, perhaps generations, to reform societies, but sports can do it much more easily through sensitisation and education. In Ahmed's case, it was staggering that a captain of an international team did not understand the enormity of using those words against a black South African cricketer. Cricket boards and franchises now have elaborate programmes to educate players about match-fixing and drug abuse, and in some cases, media management. Adding cultural sensitisation to the list would be a small task but a big step.

Calling somebody kalu in the subcontinent might not feel racist in the way the world understands it. But even without the scars of slavery and subjugation, colourism carries some of the worst features of racism; it is discriminatory, derogatory and dehumanising.

The right response to Sammy is not to question why he didn't raise the matter at the time. He has already explained that he didn't understand what the word meant. It is not even about establishing guilt and punishment. The whole episode must lead to an enquiry into our own prejudices. Cricketers are not only role models and flag bearers of the spirit of their sport. They are also, more than ever before, global citizens, and ignorance shouldn't count as an excuse or serve as a shield.

Thursday, 4 June 2020

It’s time for white people to step up for black colleagues

The protests in the US are a pivotal moment and people of colour need active allyship writes Nicola Rollock in The Financial Times

A very privileged white man recently told me with an indulgent chuckle how much he enjoyed his privilege. I was not amused. For people of colour, white privilege and power shape our lives, restrict our success and, as we were starkly reminded in recent weeks, can even kill. No matter how well-crafted an organisation’s equality and diversity policy, the claims of “tolerance” or the apparent commitment to “embracing diversity”, whiteness can crush them all — and often does.

People of colour know this. We do not need the empirical evidence to tell us that black women are more likely to die in childbirth or that black boys are more likely to be excluded from school even when engaging in the same disruptive behaviour as their white counterparts. We did not need to wait for a study to tell us that people with “foreign sounding names” have to send 74 per cent more applications than their white counterparts before being called for an interview — even when the qualifications and experience are the same.

Or that young people of colour, in the UK, are more likely to be sentenced to custody than their white peers. We do not need more reviews to tell us we are not progressing in workplaces at the same rate as our white colleagues. We already know. Many of us spend an inordinate amount of time and energy trying to work out how to survive the rules that white people make and benefit from.

While many white people seem to have discovered the horrors of racism as a result of George Floyd’s murder, it would be a mistake to overlook the pervasive racism happening around us every day. For the truth is Floyd’s murder sits at the chilling end of a continuum of racism that many of us have been talking about, shouting and protesting about for decades.

Whiteness — specifically white power — sits at the heart of racism. This is why white people are described as privileged. Privilege does not simply refer to financial or socio-economic status. It means living without the consequences of racism. Stating this is to risk the ire of most white people. They tend to become defensive, angry or deny that racism is a problem, despite the fact they have not experienced an entire life subjected to it.

Then there are the liberal intellectuals who believe they have demonstrated sufficient markers of their anti-racist credentials because they have read a bit of Kimberlé Crenshaw — the academic who coined the term “intersectionality” to describe how different forms of oppression intersect. Or, as we have seen on Twitter, there are those who quote a few lines from Martin Luther King.

Liberal intellectuals will happily make decisions about race in the workplace, argue with people of colour about race, sit on boards or committees or even become race sponsors without doing any work to understand their whiteness and how it has an impact on their assumptions and treatment of racially minoritised groups.

There are, of course, white people who imagine themselves anti-racist while doing little if anything to impact positively on the experiences of people of colour. As the author Marlon James and others have stated, being anti-racist requires action: it is not a passive state of existence.

Becoming aware of whiteness and challenging passivity or denial is an essential component of becoming a white ally. Being an ally means being willing to become the antithesis of everything white people have learnt about being white. Being humble and learning to listen actively are crucial, as a useful short video from the National Union of Students points out. This, and other videos, are easily found on YouTube and are a very accessible way for individuals and teams to go about educating themselves about allyship.

White allies do not pretend the world is living in perfect harmony, nor do they ignore or trivialise race. If the only senior Asian woman is about to leave an organisation where Asian women are under-represented and she is good at her job, white allies will flag these points to senior management and be keen to check whether there is anything that can be done to keep her. White allies are not quiet bystanders to potential or actual racial injustice.

Allyship also means letting go of the assumption that white people get to determine what constitutes racism. This is highlighted by the black lesbian feminist writer and journalist Kesiena Boom, who has written a 100-point guide to how white people can make life less frustrating for people of colour. (Sample point: “Avoid phrases like “But I have a Black friend! I can’t be racist!” You know that’s BS, as well as we do.”)

Active allyship takes effort

Being an ally means seeing race and acknowledging that white people have a racial identity. In practical terms, it means when we talk about gender, acknowledging that white women’s experiences overlap with but are different to those of women of colour. White women may be disadvantaged because of their gender, but they are privileged because of their racial identity. When we talk about social mobility, employment, education, health, policing and even which news is reported and how, race plays a role. Usually it is white people who are shaping the discourse and white people who are making the decisions.

This is evident even when white people promise commitment to racial justice in the workplace. It is usually white people who make the decision about who to appoint, the resources they will be given, what they can say and do. In their book Acting white? Rethinking race in post-racial America, US scholars Devon W Carbado and Mitu Gulati argue that white institutions tend to favour and progress people of colour who are “racially palatable” and who will do little to disrupt organisational norms. Those who are more closely aligned to their racial identity are unlikely to be seen as a fit and are, consequently, less likely to succeed.

Being a white ally takes work. It is a constant process, not a static point one arrives at and can say the job is complete. It is why despite equalities legislation, there remains a need for organisations — many of them small charities operating on tight budgets — such as the Runnymede Trust, StopWatch, InQuest, Race on the Agenda, brap and Equally Ours. Their publications offer useful resources and information about racial justice in the workplace as well as in other sectors.

There is, of course, a dark perversity to white allyship that is not often mentioned in most debates about racial justice. White allyship means divesting from the very histories, structures, systems, assumptions and behaviours that keep white people in positions of power. And, generally, power is to be maintained, not relinquished.

A very privileged white man recently told me with an indulgent chuckle how much he enjoyed his privilege. I was not amused. For people of colour, white privilege and power shape our lives, restrict our success and, as we were starkly reminded in recent weeks, can even kill. No matter how well-crafted an organisation’s equality and diversity policy, the claims of “tolerance” or the apparent commitment to “embracing diversity”, whiteness can crush them all — and often does.

People of colour know this. We do not need the empirical evidence to tell us that black women are more likely to die in childbirth or that black boys are more likely to be excluded from school even when engaging in the same disruptive behaviour as their white counterparts. We did not need to wait for a study to tell us that people with “foreign sounding names” have to send 74 per cent more applications than their white counterparts before being called for an interview — even when the qualifications and experience are the same.

Or that young people of colour, in the UK, are more likely to be sentenced to custody than their white peers. We do not need more reviews to tell us we are not progressing in workplaces at the same rate as our white colleagues. We already know. Many of us spend an inordinate amount of time and energy trying to work out how to survive the rules that white people make and benefit from.

While many white people seem to have discovered the horrors of racism as a result of George Floyd’s murder, it would be a mistake to overlook the pervasive racism happening around us every day. For the truth is Floyd’s murder sits at the chilling end of a continuum of racism that many of us have been talking about, shouting and protesting about for decades.

Whiteness — specifically white power — sits at the heart of racism. This is why white people are described as privileged. Privilege does not simply refer to financial or socio-economic status. It means living without the consequences of racism. Stating this is to risk the ire of most white people. They tend to become defensive, angry or deny that racism is a problem, despite the fact they have not experienced an entire life subjected to it.

Then there are the liberal intellectuals who believe they have demonstrated sufficient markers of their anti-racist credentials because they have read a bit of Kimberlé Crenshaw — the academic who coined the term “intersectionality” to describe how different forms of oppression intersect. Or, as we have seen on Twitter, there are those who quote a few lines from Martin Luther King.

Liberal intellectuals will happily make decisions about race in the workplace, argue with people of colour about race, sit on boards or committees or even become race sponsors without doing any work to understand their whiteness and how it has an impact on their assumptions and treatment of racially minoritised groups.

There are, of course, white people who imagine themselves anti-racist while doing little if anything to impact positively on the experiences of people of colour. As the author Marlon James and others have stated, being anti-racist requires action: it is not a passive state of existence.

Becoming aware of whiteness and challenging passivity or denial is an essential component of becoming a white ally. Being an ally means being willing to become the antithesis of everything white people have learnt about being white. Being humble and learning to listen actively are crucial, as a useful short video from the National Union of Students points out. This, and other videos, are easily found on YouTube and are a very accessible way for individuals and teams to go about educating themselves about allyship.

White allies do not pretend the world is living in perfect harmony, nor do they ignore or trivialise race. If the only senior Asian woman is about to leave an organisation where Asian women are under-represented and she is good at her job, white allies will flag these points to senior management and be keen to check whether there is anything that can be done to keep her. White allies are not quiet bystanders to potential or actual racial injustice.

Allyship also means letting go of the assumption that white people get to determine what constitutes racism. This is highlighted by the black lesbian feminist writer and journalist Kesiena Boom, who has written a 100-point guide to how white people can make life less frustrating for people of colour. (Sample point: “Avoid phrases like “But I have a Black friend! I can’t be racist!” You know that’s BS, as well as we do.”)

Active allyship takes effort

Being an ally means seeing race and acknowledging that white people have a racial identity. In practical terms, it means when we talk about gender, acknowledging that white women’s experiences overlap with but are different to those of women of colour. White women may be disadvantaged because of their gender, but they are privileged because of their racial identity. When we talk about social mobility, employment, education, health, policing and even which news is reported and how, race plays a role. Usually it is white people who are shaping the discourse and white people who are making the decisions.

This is evident even when white people promise commitment to racial justice in the workplace. It is usually white people who make the decision about who to appoint, the resources they will be given, what they can say and do. In their book Acting white? Rethinking race in post-racial America, US scholars Devon W Carbado and Mitu Gulati argue that white institutions tend to favour and progress people of colour who are “racially palatable” and who will do little to disrupt organisational norms. Those who are more closely aligned to their racial identity are unlikely to be seen as a fit and are, consequently, less likely to succeed.

Being a white ally takes work. It is a constant process, not a static point one arrives at and can say the job is complete. It is why despite equalities legislation, there remains a need for organisations — many of them small charities operating on tight budgets — such as the Runnymede Trust, StopWatch, InQuest, Race on the Agenda, brap and Equally Ours. Their publications offer useful resources and information about racial justice in the workplace as well as in other sectors.

There is, of course, a dark perversity to white allyship that is not often mentioned in most debates about racial justice. White allyship means divesting from the very histories, structures, systems, assumptions and behaviours that keep white people in positions of power. And, generally, power is to be maintained, not relinquished.

Sunday, 24 May 2020

Thursday, 14 March 2019

It's not just corruption. Entrance into elite US colleges is rigged in every way

An FBI sting revealed that wealthy parents are buying their children a place in top universities. But they’re not the only problem: the whole system is rigged writes Richard V Reeves in The Guardian

How elite US schools give preference to wealthy and white 'legacy' applicants

Or how about Jared Kushner, Donald Trump’s son-in-law? Kushner was accepted into Harvard shortly after his father donated $2.5m. An official at Kushner’s high school said there was “no way anybody in the administrative office of the school thought he would, on the merits, get into Harvard. His GPA did not warrant it, his SAT scores did not warrant it.”

David E and Stacey Goel just gave $100m to Harvard. I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that their children probably have an excellent chance of Harvard admission.

Even those parents who are not in the wealthiest brackets, but are squarely in the upper middle class, can use their money to boost their kids’ chances, through tutors, SAT prep classes, athletic coaches. Students who apply early have better chances of admission, which favors more affluent families since early admission precedes financial aid decisions. Many colleges prefer students who have “shown an interest” in their college. How to show an interest? By visiting the campus – easy for those with money for flights and hotels, less so for those on modest or low incomes.

Small wonder that at elite colleges, including most of those targeted in the corruption scheme such as Yale, Duke, Stanford and Wake Forest, take more students from families in the top 1% of the income distribution than from those in the bottom 60% combined.

So hats off to FBI special agent Bonavolonta and his team for exposing the corruption admissions. But it is in fact simply the most visible sign of a much deeper problem with college admissions. Elite colleges are serving to reinforce class inequality, rather than reduce it. The opaque, complex, unfair admissions process is a big part of the problem. From an equality perspective, it is not just Singer and his clients who are at fault: it’s the system as a whole.

‘Elite colleges are serving to reinforce class inequality, rather than reduce it.’ Photograph: Boston Globe/Boston Globe via Getty Images

Shock horror! Wealthy Americans are using their money to buy their children places at elite colleges. An FBI investigation, appropriately named Operation Varsity Blues, has exposed a $25m cash-for-admissions scandal. Coaches were allegedly bribed to declare candidates as athletic recruits; test administrators to change their scores, or allow someone else to take the test for them.

At the center of the cheating scheme was William “Rick” Singer, the founder of a for-profit college preparation business based in Newport Beach, California. Among the 33 parents caught in the FBI sting were Hollywood stars Lori Loughlin and Felicity Huffman. Loughlin starred in the series Full House. Huffman is famous for her role in Desperate Housewives; now she will be more famous as a desperate mom. And she’s not alone. The breathless anxiety among many affluent parents to get their kids into the very best colleges is a striking feature of upper-class American life.

Singer’s bribery scheme allegedly allowed parents to buy entrance for their offspring at some of the nation’s most prestigious colleges, including Yale, Georgetown University, Stanford University, UCLA, the University of San Diego, USC, University of Texas and Wake Forest.

FBI officers were at pains to point out that the colleges themselves are not being found liable; though nine athletic coaches were caught in the net.

“Following 10 months of investigation using sophisticated techniques, the FBI uncovered what we believe to be a rigged system,” John Bonavolonta, the FBI special agent in charge said, “robbing students all over the country of their right to a fair shot of getting into some of the most elite universities in this country”.

But here’s the thing: the whole system is “rigged” in favor of more affluent parents. It is true that the conversion of wealth into a desirable college seat was especially egregious in this case – to the extent that it was actually illegal. But there are countless ways that students are robbed of a “fair shot” if they are not lucky enough to be born to well-resourced, well-connected parents.

The difference between this illegal scheme and the legal ways in which money buys access is one of degree, not of kind. The mistake here was to do something illegal. Meanwhile, much of what goes on in college admissions many not be illegal, but it is immoral.

Take legacy preferences, for example. This boosts the admissions chances of the children of alumni; and for obvious reasons the alumni of elite colleges tend to be pretty affluent, especially if they marry each other. (They are also disproportionately white.) The acceptance rate for legacy applicants at Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Georgetown and Stanford is between two and three times higher than the general admission rate. If they don’t get in first time round, they might be asked to take a “gap year” and enter a year later instead, a loophole known as “Z-listing”. A Princeton study found that being a legacy applicant had the same effect as adding 160 SAT points – on the old scale up to 1600 – to a student’s application. Imagine if colleges gave that kind of admissions boost to lower-income kids?

As John W Anderson, the former co-director of college counseling at the Phillips Academy, an elite boarding school in Andover, Massachusetts, once admitted, of the students from his school who are Z-listed for Harvard, “a very, very, very high percent” are legacies. The Harvard Crimson estimates the proportion at around one in two.

Or how about donor preferences? Rather than bribing coaches, the wealthiest parents can just bribe – sorry, donate to – the college directly. In 2017, the Washington Post reported on the special treatment given to “VIP applicants” via an annual “watch list”. Applicants whose parents were big donors would have notes on their files reading “$500k. Must be on WL” (wait list). Even better, these donations are tax free!

As a general rule, the bigger the money the bigger the effect on admissions chances. Among elite aspirational alums, the question asked is “what’s the price?”. In other words, how much do you have to donate to get your child in?

Whatever the price is, those with the fattest wallets can obviously pay it. Peter Malkin graduated from Harvard Law School in 1958. He became a very wealthy real estate businessman, and huge donor. In 1985, the university’s indoor athletic facility was renamed the Malkin Athletic Center in his honor. All three of Malkin’s children went to Harvard. By 2009, five of his six college-age grandchildren had followed suit. (One brave boy dared to go to Stanford instead.)

Shock horror! Wealthy Americans are using their money to buy their children places at elite colleges. An FBI investigation, appropriately named Operation Varsity Blues, has exposed a $25m cash-for-admissions scandal. Coaches were allegedly bribed to declare candidates as athletic recruits; test administrators to change their scores, or allow someone else to take the test for them.

At the center of the cheating scheme was William “Rick” Singer, the founder of a for-profit college preparation business based in Newport Beach, California. Among the 33 parents caught in the FBI sting were Hollywood stars Lori Loughlin and Felicity Huffman. Loughlin starred in the series Full House. Huffman is famous for her role in Desperate Housewives; now she will be more famous as a desperate mom. And she’s not alone. The breathless anxiety among many affluent parents to get their kids into the very best colleges is a striking feature of upper-class American life.

Singer’s bribery scheme allegedly allowed parents to buy entrance for their offspring at some of the nation’s most prestigious colleges, including Yale, Georgetown University, Stanford University, UCLA, the University of San Diego, USC, University of Texas and Wake Forest.

FBI officers were at pains to point out that the colleges themselves are not being found liable; though nine athletic coaches were caught in the net.

“Following 10 months of investigation using sophisticated techniques, the FBI uncovered what we believe to be a rigged system,” John Bonavolonta, the FBI special agent in charge said, “robbing students all over the country of their right to a fair shot of getting into some of the most elite universities in this country”.

But here’s the thing: the whole system is “rigged” in favor of more affluent parents. It is true that the conversion of wealth into a desirable college seat was especially egregious in this case – to the extent that it was actually illegal. But there are countless ways that students are robbed of a “fair shot” if they are not lucky enough to be born to well-resourced, well-connected parents.

The difference between this illegal scheme and the legal ways in which money buys access is one of degree, not of kind. The mistake here was to do something illegal. Meanwhile, much of what goes on in college admissions many not be illegal, but it is immoral.

Take legacy preferences, for example. This boosts the admissions chances of the children of alumni; and for obvious reasons the alumni of elite colleges tend to be pretty affluent, especially if they marry each other. (They are also disproportionately white.) The acceptance rate for legacy applicants at Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Georgetown and Stanford is between two and three times higher than the general admission rate. If they don’t get in first time round, they might be asked to take a “gap year” and enter a year later instead, a loophole known as “Z-listing”. A Princeton study found that being a legacy applicant had the same effect as adding 160 SAT points – on the old scale up to 1600 – to a student’s application. Imagine if colleges gave that kind of admissions boost to lower-income kids?

As John W Anderson, the former co-director of college counseling at the Phillips Academy, an elite boarding school in Andover, Massachusetts, once admitted, of the students from his school who are Z-listed for Harvard, “a very, very, very high percent” are legacies. The Harvard Crimson estimates the proportion at around one in two.

Or how about donor preferences? Rather than bribing coaches, the wealthiest parents can just bribe – sorry, donate to – the college directly. In 2017, the Washington Post reported on the special treatment given to “VIP applicants” via an annual “watch list”. Applicants whose parents were big donors would have notes on their files reading “$500k. Must be on WL” (wait list). Even better, these donations are tax free!

As a general rule, the bigger the money the bigger the effect on admissions chances. Among elite aspirational alums, the question asked is “what’s the price?”. In other words, how much do you have to donate to get your child in?

Whatever the price is, those with the fattest wallets can obviously pay it. Peter Malkin graduated from Harvard Law School in 1958. He became a very wealthy real estate businessman, and huge donor. In 1985, the university’s indoor athletic facility was renamed the Malkin Athletic Center in his honor. All three of Malkin’s children went to Harvard. By 2009, five of his six college-age grandchildren had followed suit. (One brave boy dared to go to Stanford instead.)

How elite US schools give preference to wealthy and white 'legacy' applicants

Or how about Jared Kushner, Donald Trump’s son-in-law? Kushner was accepted into Harvard shortly after his father donated $2.5m. An official at Kushner’s high school said there was “no way anybody in the administrative office of the school thought he would, on the merits, get into Harvard. His GPA did not warrant it, his SAT scores did not warrant it.”

David E and Stacey Goel just gave $100m to Harvard. I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that their children probably have an excellent chance of Harvard admission.

Even those parents who are not in the wealthiest brackets, but are squarely in the upper middle class, can use their money to boost their kids’ chances, through tutors, SAT prep classes, athletic coaches. Students who apply early have better chances of admission, which favors more affluent families since early admission precedes financial aid decisions. Many colleges prefer students who have “shown an interest” in their college. How to show an interest? By visiting the campus – easy for those with money for flights and hotels, less so for those on modest or low incomes.

Small wonder that at elite colleges, including most of those targeted in the corruption scheme such as Yale, Duke, Stanford and Wake Forest, take more students from families in the top 1% of the income distribution than from those in the bottom 60% combined.

So hats off to FBI special agent Bonavolonta and his team for exposing the corruption admissions. But it is in fact simply the most visible sign of a much deeper problem with college admissions. Elite colleges are serving to reinforce class inequality, rather than reduce it. The opaque, complex, unfair admissions process is a big part of the problem. From an equality perspective, it is not just Singer and his clients who are at fault: it’s the system as a whole.

Saturday, 28 October 2017

Yes, we must decolonise: our teaching has to go beyond elite white men

Something is very wrong when a simple request from a large number of students, that their reading lists be broadened slightly to include some black and minority ethnic writers, becomes the basis of a manufactured racial “row”.

Priyamvada Gopal in The Guardian

Something is very wrong when a simple request from a large number of students, that their reading lists be broadened slightly to include some black and minority ethnic writers, becomes the basis of a manufactured racial “row”.

Rather than acknowledge that a major university was right to be responsive to student concerns, two British newspapers saw fit to turn an open letter from Cambridge English students into a trumped-up existential crisis for white male writers. By “decolonising” the curriculum this endangered species would now be sacrificed, apparently, like so many hapless Guys on bonfire night, to the burning fires of black and minority ethnic special interest. Nice dramatic scenario, pity about the truth content.

The real danger is that the substantive issues at stake that concern us all, not just ethnic minorities, become obscured in this facile attempt at stoking a keyboard race war with real-life consequences at a time when hate crimes are on the rise. The young people who wrote this letter, however, have an admirable clarity of vision and a robust faith in knowledge that is inspiring. They are interested in asking challenging questions about themselves and others, and how we see ourselves in relation to each other.

Decolonising the curriculum is, first of all, the acceptance that education, literary or otherwise, needs to enable self-understanding. This is particularly important to people not used to seeing themselves reflected in the mirror of conventional learning – whether women, gay people, disabled people, the working classes or ethnic minorities. Knowledge and culture is collectively produced and these groups, which intersect in different ways, have as much right as elite white men to understand what their own role has been in forging artistic and intellectual achievements.

However, it is not only about admiring yourself in the mirror – a fact that eludes those shrieking about the nonexistent elimination of straight white men from the curriculum. Real knowledge is not self-puffery, the repeated validation of oneself. In English literature, it involves learning about the lives of others, whether these be Robert Wedderburn, the fiery black Scottish working-class preacher who believed in self-emancipation; the working-class poet Robert Bloomfield; or Una Marson, the suffragist and broadcaster who wrote eloquently about race and the colour-bar in Britain as well as resonant poetry about her native Jamaica.

Cape Coast Castle, Ghana: ‘Our students have rightly asked to know more about the colonial context in which much English literature was produced.’ Photograph: Alamy

Surely, Sultana’s Dream, the early 20th-century fantasy story by Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain – where men stayed home while only women went out – has a relevance for our understanding of Muslim women’s long and rich history of writing and debate. (Yes, it exists.)

To decolonise and not just diversify curriculums is to recognise that knowledge is inevitably marked by power relations. In a society still shaped by a long colonial history in which straight white upper-class men are at the top of the social order, most disciplines give disproportionate prominence to the experiences, concerns and achievements of this one group. In my native India, upper-caste Hindu men have long held sway over learning and efforts are being made, in the face of predictable resistance, to dislodge that supremacy.

Britain has a long history of black and Asian communities that contributed significantly to its wealth and heritage

A decolonised curriculum would bring questions of class, caste, race, gender, ability and sexuality into dialogue with each other, instead of pretending that there is some kind of generic identity we all share.

It is telling that efforts to inject some breadth and variety into teaching are being dismissed as “artificial balance”. The assumption here is precisely the problem – that the best of all that has been thought and said just happens to have been produced in the west by white upper-class people, largely men.

Scholars such as Peter Fryer and Rozina Visram have shown that black and Asian people have a history in Britain that stretches back nearly 500 years, and that these communities contributed significantly to its wealth and heritage. In fact, the very idea of what it meant to be “white” or “English” relied on the presence of those, including the Irish, who could be marked as neither.

Yet decolonisation is not just about bringing in minority texts but also how we read “traditional” texts. Our students have rightly asked to know more about the colonial context in which much English literature was produced – indeed, in which the very idea of “English” literature came to be.

The British empire, love it or loathe it, paradoxically provides the common ground upon which our histories and identities were forged, whether those be of a white Etonian with Sandhurst military training or a queer British Asian female social worker. Between total denial of imperial history and mindless celebration of it comes actual knowledge of what happened. British literature has a great dissident tradition which acknowledges this. Barry Unsworth’s magisterial 1992 Booker prizewinner, Sacred Hunger, a powerful novel set in the context of the triangular slave trade of the 18th century, shows how the emergence of capitalist greed, the “sacred” unquestionable value, inflicted suffering on black men and women, and on working-class Britons, in different ways.

Ultimately, to decolonise is to ask difficult questions of ourselves. The Antiguan author Jamaica Kincaid puts it thus: “And might not knowing why they are the way they are, why they do the things they do, why they live the way they live, why the things that happened to them happened, lead … people to a different relationship with the world, a more demanding relationship?” Our students have chosen the demanding way.

To decolonise and not just diversify curriculums is to recognise that knowledge is inevitably marked by power relations. In a society still shaped by a long colonial history in which straight white upper-class men are at the top of the social order, most disciplines give disproportionate prominence to the experiences, concerns and achievements of this one group. In my native India, upper-caste Hindu men have long held sway over learning and efforts are being made, in the face of predictable resistance, to dislodge that supremacy.

Britain has a long history of black and Asian communities that contributed significantly to its wealth and heritage

A decolonised curriculum would bring questions of class, caste, race, gender, ability and sexuality into dialogue with each other, instead of pretending that there is some kind of generic identity we all share.

It is telling that efforts to inject some breadth and variety into teaching are being dismissed as “artificial balance”. The assumption here is precisely the problem – that the best of all that has been thought and said just happens to have been produced in the west by white upper-class people, largely men.

Scholars such as Peter Fryer and Rozina Visram have shown that black and Asian people have a history in Britain that stretches back nearly 500 years, and that these communities contributed significantly to its wealth and heritage. In fact, the very idea of what it meant to be “white” or “English” relied on the presence of those, including the Irish, who could be marked as neither.

Yet decolonisation is not just about bringing in minority texts but also how we read “traditional” texts. Our students have rightly asked to know more about the colonial context in which much English literature was produced – indeed, in which the very idea of “English” literature came to be.

The British empire, love it or loathe it, paradoxically provides the common ground upon which our histories and identities were forged, whether those be of a white Etonian with Sandhurst military training or a queer British Asian female social worker. Between total denial of imperial history and mindless celebration of it comes actual knowledge of what happened. British literature has a great dissident tradition which acknowledges this. Barry Unsworth’s magisterial 1992 Booker prizewinner, Sacred Hunger, a powerful novel set in the context of the triangular slave trade of the 18th century, shows how the emergence of capitalist greed, the “sacred” unquestionable value, inflicted suffering on black men and women, and on working-class Britons, in different ways.

Ultimately, to decolonise is to ask difficult questions of ourselves. The Antiguan author Jamaica Kincaid puts it thus: “And might not knowing why they are the way they are, why they do the things they do, why they live the way they live, why the things that happened to them happened, lead … people to a different relationship with the world, a more demanding relationship?” Our students have chosen the demanding way.

Thursday, 11 May 2017

Noam Chomsky on worldwide anger

Labour party’s future lies with Momentum, says Noam Chomsky

Anushka Asthana in The Guardian

Professor Noam Chomsky has claimed that any serious future for the Labour party must come from the leftwing pressure group Momentum and the army of new members attracted by the party’s leadership.

In an interview with the Guardian, the radical intellectual threw his weight behind Jeremy Corbyn, claiming that Labour would be doing far better in opinion polls if it were not for the “bitter” hostility of the mainstream media. “If I were a voter in Britain, I would vote for him,” said Chomsky, who admitted that the current polling position suggested Labour was not yet gaining popular support for the policy positions that he supported.

“There are various reasons for that – partly an extremely hostile media, partly his own personal style which I happen to like but perhaps that doesn’t fit with the current mood of the electorate,” he said. “He’s quiet, reserved, serious, he’s not a performer. The parliamentary Labour party has been strongly opposed to him. It has been an uphill battle.”

He said there were a lot of factors involved, but insisted that Labour would not be trailing the Conservatives so heavily in the polls if the media was more open to Corbyn’s agenda. “If he had a fair treatment from the media – that would make a big difference.”

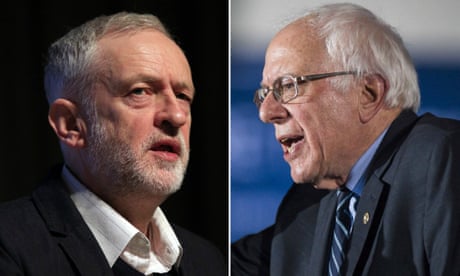

Asked what motivation he thought newspapers had to oppose Corbyn, Chomsky said the Labour leader had, like Bernie Sanders in the US, broken out of the “elite, liberal consensus” that he claimed was “pretty conservative”.

The academic, who is in Britain to deliver a lecture at the University of Reading on what he believes is the deteriorating state of western democracy, claimed that voters had turned to the Conservatives in recent years because of “an absence of anything else”.

“The shift in the Labour party under [Tony] Blair made it a pale image of the Conservatives which, given the nature of the policies and their very visible results, had very little appeal for good reasons.”

He said Labour needed to “reconstruct itself” in the interests of working people, with concerns about human and civil rights at its core, arguing that such a programme could appeal to the majority of people.

But ahead of what could be a bitter split within the Labour movement if Corbyn’s party is defeated in the June election, Chomsky claimed the future must lie with the left of the party. “The constituency of the Labour party, the new participants, the Momentum group and so on … if there is to be a serious future for the Labour party that is where it is in my opinion,” he said.

The comments came as Chomsky prepared to deliver a university lecture entitled Racing for the precipice: is the human experiment doomed?

He told the Guardian that he believed people had created a “perfect storm” in which the key defence against the existential threats of climate change and the nuclear age were being radically weakened.

“Each of those is a major threat to survival, a threat that the human species has never faced before, and the third element of this pincer is that the socio-economic programmes, particularly in the last generation, but the political culture generally has undermined the one potential defence against these threats,” he said.

Chomsky described the defence as a “functioning democratic society with engaged, informed citizens deliberating and reaching measures to deal with and overcome the threats”.

Professor Noam Chomsky has claimed that any serious future for the Labour party must come from the leftwing pressure group Momentum and the army of new members attracted by the party’s leadership.

In an interview with the Guardian, the radical intellectual threw his weight behind Jeremy Corbyn, claiming that Labour would be doing far better in opinion polls if it were not for the “bitter” hostility of the mainstream media. “If I were a voter in Britain, I would vote for him,” said Chomsky, who admitted that the current polling position suggested Labour was not yet gaining popular support for the policy positions that he supported.

“There are various reasons for that – partly an extremely hostile media, partly his own personal style which I happen to like but perhaps that doesn’t fit with the current mood of the electorate,” he said. “He’s quiet, reserved, serious, he’s not a performer. The parliamentary Labour party has been strongly opposed to him. It has been an uphill battle.”

He said there were a lot of factors involved, but insisted that Labour would not be trailing the Conservatives so heavily in the polls if the media was more open to Corbyn’s agenda. “If he had a fair treatment from the media – that would make a big difference.”

Asked what motivation he thought newspapers had to oppose Corbyn, Chomsky said the Labour leader had, like Bernie Sanders in the US, broken out of the “elite, liberal consensus” that he claimed was “pretty conservative”.

The academic, who is in Britain to deliver a lecture at the University of Reading on what he believes is the deteriorating state of western democracy, claimed that voters had turned to the Conservatives in recent years because of “an absence of anything else”.

“The shift in the Labour party under [Tony] Blair made it a pale image of the Conservatives which, given the nature of the policies and their very visible results, had very little appeal for good reasons.”

He said Labour needed to “reconstruct itself” in the interests of working people, with concerns about human and civil rights at its core, arguing that such a programme could appeal to the majority of people.

But ahead of what could be a bitter split within the Labour movement if Corbyn’s party is defeated in the June election, Chomsky claimed the future must lie with the left of the party. “The constituency of the Labour party, the new participants, the Momentum group and so on … if there is to be a serious future for the Labour party that is where it is in my opinion,” he said.

The comments came as Chomsky prepared to deliver a university lecture entitled Racing for the precipice: is the human experiment doomed?

He told the Guardian that he believed people had created a “perfect storm” in which the key defence against the existential threats of climate change and the nuclear age were being radically weakened.

“Each of those is a major threat to survival, a threat that the human species has never faced before, and the third element of this pincer is that the socio-economic programmes, particularly in the last generation, but the political culture generally has undermined the one potential defence against these threats,” he said.

Chomsky described the defence as a “functioning democratic society with engaged, informed citizens deliberating and reaching measures to deal with and overcome the threats”.

He blamed neoliberal policies for the breakdown in democracy, saying they had transferred power from public institutions to markets and deregulated financial institutions while failing to benefit ordinary people.

“In 2007 right before the great crash, when there was euphoria about what was called the ‘great moderation’, the wonderful economy, at that point the real wages of working people were lower – literally lower – than they had been in 1979 when the neoliberal programmes began. You had a similar phenomenon in England.”

Chomsky claimed that the disillusionment that followed gave rise to the surge of anti-establishment movements – including Donald Trump and Brexit, but also Emmanuel Macron’s victory in France and the rise of Corbyn and Sanders.

“The Sanders achievement was maybe the most surprising and significant aspect of the November election,” he said. “Sanders broke from a century of history of pretty much bought elections. That is a reflection of the decline of how political institutions are perceived.”

But he said the positions the US senator, who challenged Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination, had taken would not have surprised Dwight Eisenhower, who was US president in the 1950s.

“[Eisenhower] said no one belongs in a political system who questions the right of workers to organise freely, to form powerful unions. Sanders called it a political revolution but it was to a large extent an effort to return to the new deal policies that were the basis for the great growth period of the 1950s and 1960s.”

Chomsky argued that Corbyn stood in the same tradition.

Wednesday, 11 January 2017

SOAS students have a point. Philosophy degrees should look beyond white Europeans

Tom Whyman in The Guardian