The sprawling factory compound, all grey dormitories and weather-beaten warehouses, blends seamlessly into the outskirts of the Shenzhen megalopolis. Foxconn’s enormous Longhua plant is a major manufacturer of Apple products. It might be the best-known factory in the world; it might also might be among the most secretive and sealed-off. Security guards man each of the entry points. Employees can’t get in without swiping an ID card; drivers entering with delivery trucks are subject to fingerprint scans. A Reuters journalist was once dragged out of a car and beaten for taking photos from outside the factory walls. The warning signs outside – “This factory area is legally established with state approval. Unauthorised trespassing is prohibited. Offenders will be sent to police for prosecution!” – are more aggressive than those outside many Chinese military compounds.

But it turns out that there’s a secret way into the heart of the infamous operation: use the bathroom. I couldn’t believe it. Thanks to a simple twist of fate and some clever perseverance by my fixer, I’d found myself deep inside so-called Foxconn City.

It’s printed on the back of every iPhone: “Designed by Apple in California Assembled in China”. US law dictates that products manufactured in China must be labelled as such and Apple’s inclusion of the phrase renders the statement uniquely illustrative of one of the planet’s starkest economic divides – the cutting edge is conceived and designed in Silicon Valley, but it is assembled by hand in China.

The vast majority of plants that produce the iPhone’s component parts and carry out the device’s final assembly are based here, in the People’s Republic, where low labour costs and a massive, highly skilled workforce have made the nation the ideal place to manufacture iPhones (and just about every other gadget). The country’s vast, unprecedented production capabilities – the US Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that as of 2009 there were 99 million factory workers in China – have helped the nation become the world’s second largest economy. And since the first iPhone shipped, the company doing the lion’s share of the manufacturing is the Taiwanese Hon Hai Precision Industry Co, Ltd, better known by its trade name, Foxconn.

Foxconn is the single largest employer in mainland China; there are 1.3 million people on its payroll. Worldwide, among corporations, only Walmart and McDonald’s employ more. As many people work for Foxconn as live in Estonia.

An employee directs jobseekers to queue up at the Foxconn recruitment centre in Shenzhen. Photograph: David Johnson/Reuters

Today, the iPhone is made at a number of different factories around China, but for years, as it became the bestselling product in the world, it was largely assembled at Foxconn’s 1.4 square-mile flagship plant, just outside Shenzhen. The sprawling factory was once home to an estimated 450,000 workers. Today, that number is believed to be smaller, but it remains one of the biggest such operations in the world. If you know of Foxconn, there’s a good chance it’s because you’ve heard of the suicides. In 2010, Longhua assembly-line workers began killing themselves. Worker after worker threw themselves off the towering dorm buildings, sometimes in broad daylight, in tragic displays of desperation – and in protest at the work conditions inside. There were 18 reported suicide attempts that year alone and 14 confirmed deaths. Twenty more workers were talked down by Foxconn officials.

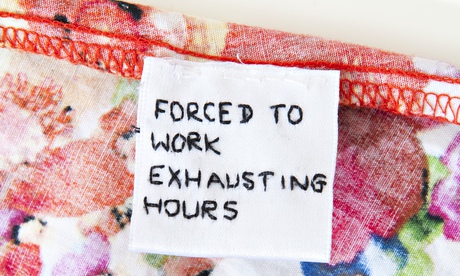

The epidemic caused a media sensation – suicides and sweatshop conditions in the House of iPhone. Suicide notes and survivors told of immense stress, long workdays and harsh managers who were prone to humiliate workers for mistakes, of unfair fines and unkept promises of benefits.

The corporate response spurred further unease: Foxconn CEO, Terry Gou, had large nets installed outside many of the buildings to catch falling bodies. The company hired counsellors and workers were made to sign pledges stating they would not attempt to kill themselves.

Steve Jobs, for his part, declared: “We’re all over that” when asked about the spate of deaths and he pointed out that the rate of suicides at Foxconn was within the national average. Critics pounced on the comment as callous, though he wasn’t technically wrong. Foxconn Longhua was so massive that it could be its own nation-state, and the suicide rate was comparable to its host country’s. The difference is that Foxconn City is a nation-state governed entirely by a corporation and one that happened to be producing one of the most profitable products on the planet.

If the boss finds any problems, they don’t scold you then. They scold you later, in front of everyone, at a meeting

A cab driver lets us out in front of the factory; boxy blue letters spell out Foxconn next to the entrance. The security guards eye us, half bored, half suspicious. My fixer, a journalist from Shanghai whom I’ll call Wang Yang, and I decide to walk the premises first and talk to workers, to see if there might be a way to get inside.

The first people we stop turn out to be a pair of former Foxconn workers.

“It’s not a good place for human beings,” says one of the young men, who goes by the name Xu. He’d worked in Longhua for about a year, until a couple of months ago, and he says the conditions inside are as bad as ever. “There is no improvement since the media coverage,” Xu says. The work is very high pressure and he and his colleagues regularly logged 12-hour shifts. Management is both aggressive and duplicitous, publicly scolding workers for being too slow and making them promises they don’t keep, he says. His friend, who worked at the factory for two years and chooses to stay anonymous, says he was promised double pay for overtime hours but got only regular pay. They paint a bleak picture of a high-pressure working environment where exploitation is routine and where depression and suicide have become normalised.

“It wouldn’t be Foxconn without people dying,” Xu says. “Every year people kill themselves. They take it as a normal thing.”

Over several visits to different iPhone assembly factories in Shenzhen and Shanghai, we interviewed dozens of workers like these. Let’s be honest: to get a truly representative sample of life at an iPhone factory would require a massive canvassing effort and the systematic and clandestine interviewing of thousands of employees. So take this for what it is: efforts to talk to often skittish, often wary and often bored workers who were coming out of the factory gates, taking a lunch break or congregating after their shifts.

A Foxconn employee in a dormitory at Longhua. The rooms are currently said to sleep eight. Photograph: Wang Yishu / Imaginechina/Camera Press

The vision of life inside an iPhone factory that emerged was varied. Some found the work tolerable; others were scathing in their criticisms; some had experienced the despair Foxconn was known for; still others had taken a job just to try to find a girlfriend. Most knew of the reports of poor conditions before joining, but they either needed the work or it didn’t bother them. Almost everywhere, people said the workforce was young and turnover was high. “Most employees last only a year,” was a common refrain. Perhaps that’s because the pace of work is widely agreed to be relentless, and the management culture is often described as cruel.

Since the iPhone is such a compact, complex machine, putting one together correctly requires sprawling assembly lines of hundreds of people who build, inspect, test and package each device. One worker said 1,700 iPhones passed through her hands every day; she was in charge of wiping a special polish on the display. That works out at about three screens a minute for 12 hours a day.

More meticulous work, like fastening chip boards and assembling back covers, was slower; these workers have a minute apiece for each iPhone. That’s still 600 to 700 iPhones a day. Failing to meet a quota or making a mistake can draw public condemnation from superiors. Workers are often expected to stay silent and may draw rebukes from their bosses for asking to use the restroom.

Xu and his friend were both walk-on recruits, though not necessarily willing ones. “They call Foxconn a fox trap,” he says. “Because it tricks a lot of people.” He says Foxconn promised them free housing but then forced them to pay exorbitantly high bills for electricity and water. The current dorms sleep eight to a room and he says they used to be 12 to a room. But Foxconn would shirk social insurance and be late or fail to pay bonuses. And many workers sign contracts that subtract a hefty penalty from their pay if they quit before a three-month introductory period.

The body-catching nets are still there. They look a bit like tarps that have blown off the things they’re meant to cover

On top of that, the work is gruelling. “You have to have mental management,” says Xu, otherwise you can get scolded by bosses in front of your peers. Instead of discussing performance privately or face to face on the line, managers would stockpile complaints until later. “When the boss comes down to inspect the work,” Xu’s friend says, “if they find any problems, they won’t scold you then. They will scold you in front of everyone in a meeting later.”

“It’s insulting and humiliating to people all the time,” his friend says. “Punish someone to make an example for everyone else. It’s systematic,” he adds. In certain cases, if a manager decides that a worker has made an especially costly mistake, the worker has to prepare a formal apology. “They must read a promise letter aloud – ‘I won’t make this mistake again’– to everyone.”

This culture of high-stress work, anxiety and humiliation contributes to widespread depression. Xu says there was another suicide a few months ago. He saw it himself. The man was a student who worked on the iPhone assembly line. “Somebody I knew, somebody I saw around the cafeteria,” he says. After being publicly scolded by a manager, he got into a quarrel. Company officials called the police, though the worker hadn’t been violent, just angry.

“He took it very personally,” Xu says, “and he couldn’t get through it.” Three days later, he jumped out of a ninth-storey window.

So why didn’t the incident get any media coverage? I ask. Xu and his friend look at each other and shrug. “Here someone dies, one day later the whole thing doesn’t exist,” his friend says. “You forget about it.”

Employees have lunch in a vast refectory at the Foxconn Longhua plant. Photograph: Wang Yishu/Imaginechina/Camera Press

‘We look at everything at these companies,” Steve Jobs said after news of the suicides broke. “Foxconn is not a sweatshop. It’s a factory – but my gosh, they have restaurants and movie theatres… but it’s a factory. But they’ve had some suicides and attempted suicides – and they have 400,000 people there. The rate is under what the US rate is, but it’s still troubling.” Apple CEO, Tim Cook, visited Longhua in 2011 and reportedly met suicide-prevention experts and top management to discuss the epidemic.

In 2012, 150 workers gathered on a rooftop and threatened to jump. They were promised improvements and talked down by management; they had, essentially, wielded the threat of killing themselves as a bargaining tool. In 2016, a smaller group did it again. Just a month before we spoke, Xu says, seven or eight workers gathered on a rooftop and threatened to jump unless they were paid the wages they were due, which had apparently been withheld. Eventually, Xu says, Foxconn agreed to pay the wages and the workers were talked down.

When I ask Xu about Apple and the iPhone, his response is swift: “We don’t blame Apple. We blame Foxconn.” When I ask the men if they would consider working at Foxconn again if the conditions improved, the response is equally blunt. “You can’t change anything,” Xu says. “It will never change.”

Wang and I set off for the main worker entrance. We wind around the perimeter, which stretches on and on – we have no idea this is barely a fraction of the factory at this point.

After walking along the perimeter for 20 minutes or so, we come to another entrance, another security checkpoint. That’s when it hits me. I have to use the bathroom. Desperately. And that gives me an idea.

There’s a bathroom in there, just a few hundred feet down a stairwell by the security point. I see the universal stick-man signage and I gesture to it. This checkpoint is much smaller, much more informal. There’s only one guard, a young man who looks bored. Wang asks something a little pleadingly in Chinese. The guard slowly shakes his head no, looks at me. The strain on my face is very, very real. She asks again – he falters for a second, then another no.

We’ll be right back, she insists, and now we’re clearly making him uncomfortable. Mostly me. He doesn’t want to deal with this. Come right back, he says. Of course, we don’t.

To my knowledge, no American journalist has been inside a Foxconn plant without permission and a tour guide, without a carefully curated visit to selected parts of the factory to demonstrate how OK things really are.

Maybe the most striking thing, beyond its size – it would take us nearly an hour to briskly walk across Longhua – is how radically different one end is from the other. It’s like a gentrified city in that regard. On the outskirts, let’s call them, there are spilt chemicals, rusting facilities and poorly overseen industrial labour. The closer you get to the city centre – remember, this is a factory – the more the quality of life, or at least the amenities and the infrastructure, improves.

‘Not a good place for human beings’: Foxconn Longhua. Photograph: Brian Merchant

As we get deeper in, surrounded by more and more people, it feels like we’re getting noticed less. The barrage of stares mutates into disinterested glances. My working theory: the plant is so vast, security so tight, that if we are inside just walking around, we must have been allowed to do so. That or nobody really gives a shit. We start trying to make our way to the G2 factory block, where we’ve been told iPhones are made. After leaving “downtown”, we begin seeing towering, monolithic factory blocks – C16, E7 and so on, many surrounded by crowds of workers.

I worry about getting too cavalier and remind myself not to push it; we’ve been inside Foxconn for almost an hour now. The crowds have been thinning out the farther away from the centre we get. Then there it is: G2. It’s identical to the factory blocks that cluster around it, that threaten to fade into the background of the smoggy static sky.

G2 looks deserted, though. A row of impossibly rusted lockers runs outside the building. No one’s around. The door is open, so we go in. To the left, there’s an entry to a massive, darkened space; we’re heading for that when someone calls out. A floor manager has just come down the stairs and he asks us what we’re doing. My translator stammers something about a meeting and the man looks confused; then he shows us the computer monitoring system he uses to oversee production on the floor. There’s no shift right now, he says, but this is how they watch.

No sign of iPhones, though. We keep walking. Outside G3, teetering stacks of black gadgets wrapped in plastic sit in front of what looks like another loading zone. A couple of workers on smartphones drift by us. We get close enough to see the gadgets through the plastic and, nope, not iPhones either. They look like Apple TVs, minus the company logo. There are probably thousands stacked here, awaiting the next step in the assembly line.

If this is indeed where iPhones and Apple TVs are made, it’s a fairly aggressively shitty place to spend long days, unless you have a penchant for damp concrete and rust. The blocks keep coming, so we keep walking. Longhua starts to feel like the dull middle of a dystopian novel, where the dread sustains but the plot doesn’t.

We could keep going, but to our left, we see what look like large housing complexes, probably the dormitories, complete with cagelike fences built out over the roof and the windows, and so we head in that direction. The closer we get to the dorms, the thicker the crowds get and the more lanyards and black glasses and faded jeans and sneakers we see. College-age kids are gathered, smoking cigarettes, crowded around picnic tables, sitting on kerbs.

And, yes, the body-catching nets are still there. Limp and sagging, they give the impression of tarps that have half blown off the things they’re supposed to cover. I think of Xu, who said: “The nets are pointless. If somebody wants to commit suicide, they will do it.”

We are drawing stares again – away from the factories, maybe folks have more time and reason to indulge their curiosity. In any case, we’ve been inside Foxconn for an hour. I have no idea if the guard put out an alert when we didn’t come back from the bathroom or if anyone is looking for us or what. The sense that it’s probably best not to push it prevails, even though we haven’t made it on to a working assembly line.

A protester dressed as a factory worker outside an Apple retail outlet in Hong Kong, May 2011. Photograph: Antony Dickson/AFP/Getty Images

We head back the way we came. Before long, we find an exit. It’s pushing evening as we join a river of thousands and, heads down, shuffle through the security checkpoint. Nobody says a word. Getting out of the haunting megafactory is a relief, but the mood sticks. No, there were no child labourers with bleeding hands pleading at the windows. There were a number of things that would surely violate the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration code – unprotected construction workers, open chemical spillage, decaying, rusted structures, and so on – but there are probably a lot of things at US factories that would violate OSHA code too. Apple may well be right when it argues that these facilities are nicer than others out there. Foxconn was not our stereotypical conception of a sweatshop. But there was a different kind of ugliness. For whatever reason – the rules imposing silence on the factory floors, its pervasive reputation for tragedy or the general feeling of unpleasantness the environment itself imparts – Longhua felt heavy, even oppressively subdued.

When I look back at the photos I snapped, I can’t find one that has someone smiling in it. It does not seem like a surprise that people subjected to long hours, repetitive work and harsh management might develop psychological issues. That unease is palpable – it’s worked into the environment itself. As Xu said: “It’s not a good place for human beings.”