We know more about the conditions of our battery hens than of our battery textile workers. A year after Rana Plaza, it's time we were given the facts

'Forcing businesses to admit exactly who is responsible for their economic success, and who reaps the profits, is a good start'. Illustration: Daniel Pudles

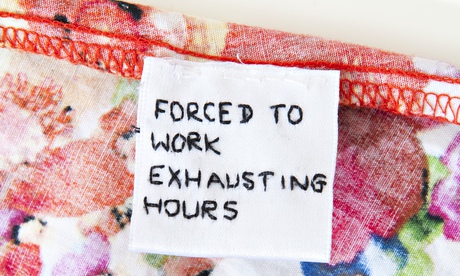

Somewhere in Swansea is a woman whose hand I want to shake. My guess is that she's the one responsible for giving Primark such a stonking headache over the past few days. You probably know her handiwork – at least, you will if you saw the stories about how two Swansea shoppers came back from the local Primark with bargain dresses mysteriously bearing extra labels. One read "'Degrading' sweatshop conditions"; another "Forced to work exhausting hours".

How did they get there? "Cries for help" from a production line in deepest Dhaka, claim the merchants of journalese. But surely no machinist could bunk off their punishing workload to script these complaints in pristine English, stitch them in and whisk them past a pin-sharp inspector. The much-more-likely scenario is an activist, holed up in a south Wales fitting room, hastily darning her protests.

In which case: well-needled, that woman. Not only has she gummed up the Primark publicity machine for days on end and brought back into discussion the costs of cheap fashion, she's also given pause to two shoppers. In the words of one: "I've never really thought much about how the clothes are made … I dread to think that my summer top may be made by some exhausted person toiling away for hours in some sweatshop."

In a mall, such thinking counts as disruptive activity. The lexicon for most retailers runs from impulse buy to splurge to treat; they prefer us to wander the aisles with our eyes wide open and our minds shut tight. The whole point of a shopping environment is to drown out those inconvenient headlines about dead textile workers in Rana Plaza with a bit of Ellie Goulding and a lot of advertising. Which is what makes the Primark protests, or the Tesco shelfie campaign, or the UK Uncut rallies so splendidly aggravating – because they undercut the multimillion-pound marketing with point of sale information about poverty pay for shop staff or high-street tax dodging.

They also underline how little we're told about what we're paying for. Look at the label sewn into your top: the only thing it must tell you under law is which fibres it's made out of – whether it's cotton or acrylic or whatever. Which country your shirt came from, or the accuracy of the sizing – such essentials are in the gift of the retailer. A similarly light-touch regime holds for food: after years of fighting between consumer groups and the (now eviscerated) Food Standards Agency, and big-spending food manufacturers, a new set of traffic-light labels will be introduced. Thanks to heavy industrial lobbying, it will still be completely voluntary.

How much sugar is in your bowl of Frosties: this is a basic fact, yet it remains up to the seller how they present it to you. By law you are entitled to more information about the production of your eggs than your underwear. Under current regulations, we know more about our battery hens than we do about our battery textile workers.

A ‘cry for help' label in a top from Primark in Swansea. ‘Big retailers can also display prominently how much tax they pay, and what they pay both top staff and shopfloor employees.' Photograph: Matthew Horwood/Wales News Service

A ‘cry for help' label in a top from Primark in Swansea. ‘Big retailers can also display prominently how much tax they pay, and what they pay both top staff and shopfloor employees.' Photograph: Matthew Horwood/Wales News Service

Consider: just over a year has passed since the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory, which saw more than 1,100 staff crushed to death and another 2,500 injured, many permanently disabled. Those people and the thousands of others working in similarly precarious and punishing conditions make the garments we wear and the electronic goods we fiddle about with. Yet they rate barely a mention. Outsourcing and globalisation may have brought down the price of our shopping, but it has also enabled retailers to engage in a facade of blame-shifting and plausible deniability: for Apple to pass the buck for suicidal Chinese workers on to Foxconn and duck the questions about how much of a margin it pays suppliers.

So here's a modest proposal: a new law that mandates more, and more relevant information, on the products we buy. Call it the Truth on the Label Act, which will require shops to display where their goods are made, which chemicals were used in production, and whether the factory is unionised. Stick it on the shelves, print it on the clothes tags. Big retailers can also display prominently in each branch how much tax they pay, and what they pay both top staff and shopfloor employees.

That's because while queuing up for the self-service checkout, hungry commuters might want to know that the boss of Tesco's, Philip Clarke, is paid 135 times what his lowest-paid member of staff is. Or that George Weston, chief executive of Primark's parent company, received over £5m last year, while the young women who sew his firm's T-shirts get less than £30 a month.

Such information is not hard for the big retailers to provide. Long before Google was an algorithm in a programmer's eye, Tesco was in the data-collection business. This information in itself won't change an entire economic system. But forcing businesses to admit exactly who is responsible for their economic success, and who reaps the profits, is a good start. Otherwise, we're entirely dependent on activists in changing rooms.