'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Tuesday, 30 April 2024

Wednesday, 14 February 2024

Friday, 23 June 2023

Britain is the Dorian Gray economy, hiding its ugly truths from the world. Now they are exposed

You know the central conceit of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, of course you do. A lad of sun-kissed beauty is presented with a stunning likeness of himself. Disturbed at the notion that he will grow old while the painting doesn’t, he locks it away – where it is the portrait that ages and uglifies while Dorian stays boyish and beautiful. But perhaps you’ve forgotten what happens next.

The story has come to my mind many times, as the foulness of British politics becomes ever harder to ignore. Genteel liberals wonder how their land of cricket whites and orderly queues could be ruled by a grasping liar such as Boris Johnson and I hear a whisper on the wind: Dorian Gray. The New York Times and Der Spiegel report in bewilderment on a country with pockets of deep poverty and unslaked anger, and again rasps that hoarse voice: the horror was hidden here all along.

Now it’s all out in the open. In one of the richest societies in human history, inhabitants are starting to twig that by 2030 or thereabouts they will earn less per head than the Poles they so recently patronised. Whatever the politicians and pundits may argue, this debacle owes nothing to Jeremy Corbyn or Brexit or any supposedly un-British “populism”. It is homegrown and has deep roots.

Like Dorian Gray, Britain has for too long presented one face to the world while concealing the awful truth. The author of that novel, Oscar Wilde, was the son of an Irish nationalist and a graduate of Oxford, where he became a fine student of the British upper classes and their mellifluous hypocrisy. He would have recognised much of the mess we’re in, because it grew among shadows and cover-ups. From Tony Blair’s Cool Britannia through to George Osborne’s “march of the makers”, our rulers have trumpeted every false success, while ugly facts have been waved away as anomalies: from the former manufacturing suburbs and towns turned into giant warehouses of surplus people, to the fact that 15% of adults in England are on antidepressants. We’re winning the global race, claimed David Cameron, even as the population’s life expectancy fell far behind other rich countries. We shan’t stunt future generations with debt, he boasted, as our five-year-olds became the shortest in Europe.

Or take the housing bubble that politicians pretended was true prosperity – until this week, as the Bank of England hiked rates for the 13th time in a row and the prospect of it bursting began to terrify them. Yet the Westminster classes blew their hardest into that bubble. As soon as estate agents were out of lockdown, Rishi Sunak gave up £6bn of taxpayers’ money for a stamp duty holiday – an act as prudent as pouring petrol on a fire. Many of those he lured up the property ladder will be hardest hit by rising mortgage rates. Analysis done for me by UK Finance suggests that 465,000 house purchases during that tax break were financed with two- or three-year fixed rate mortgages – the very ones running out right now. In other words, nearly half a million households took the chancellor’s inducement; many will plunge into dangerous financial straits; some face losing their homes. They were mis-sold a dream by Sunak. Still, at least the Tories enjoyed a bounce in the polls.

“Sin is a thing that writes itself across a man’s face,” Dorian is told by his portraitist Basil Hallward. “If a wretched man has a vice, it shows itself in the lines of his mouth, the droop of his eyelids, the moulding of his hands even … But you, Dorian, with your pure, bright, innocent face and your marvellous untroubled youth – I can’t believe anything against you.” The picture of Dorian, which would have revealed the grotesque truth, is hidden away. So, too, has the UK avoided admitting its ills. Even now, in a country where patently so little works for people who rely on work for their income, commentators and frontbenchers still blame supposedly all-powerful interlopers: Boris, Nigel, Jeremy. And from Sunak to Starmer, all push growth and jobs as the remedy for what ails us.

Yet growth in this country is falling and not because of Ukraine or Covid or Brexit. Since the 1950s, the growth rate adjusted for inflation has been on a gentle but insistent downward slide. Our economy has become ever more stagnant and dependent on debt. It is fatuous to pretend this is going to turn around through magicking Britain into an AI free-for-all or a jolly green industrial giant. Employment? One in four employees are on low weekly wages – either because the pay is too low or the hours aren’t enough – while the average real wage has flatlined for many years.

Much of this analysis comes from a new book, When Nothing Works, written by a team of scholars. Although specialising in economics and accountancy, what they have produced is an essential text for understanding British government: the polarised politics of a highly unequal and increasingly stagnant society.

Take the issue at the top of today’s agenda: wages. Why can’t you and I take home more money? Because of a lack of productivity, politicians will say. Yet the researchers point to how labour has got a smaller and smaller share of economic output since the 1970s.

If the same share of GDP was paid out in wages today as in 1976, the average working-age household would have an extra £9,744 a year. We haven’t lost that 10 grand a year through laziness at work but because politicians from Thatcher onwards smashed up trade unions, undermined labour rights, and crowed over the result as a “flexible labour market”. What they really created was a low-wage workforce, in a low-growth country ruled by politicians with low ambitions for everyone bar themselves.

“The prayer of your pride has been answered,” Basil counsels Dorian, when he finally sees the portrait and its horrific truth. “The prayer of your repentance will be answered also.” When Nothing Works will inevitably be termed pessimistic, but it is no such thing. Realism comes from facing who we are and dropping the pretence that a growth miracle is just around the corner. Instead of trying to boost “the economy”, it is high time to boost our people: to ensure they have the basics they need to live a life free from indignity and free to flourish. This will come from redistribution rather than growth, from replacing extractive businesses with fair ones. Such ideas will not go down well in SW1, where both Tory and Labour are increasingly hostile to pluralism and brittle in their dogmatism. Self-knowledge is the hardest knowledge, as one of the book’s authors, Karel Williams, says. And self-delusion leads eventually to disaster.

Unable to face his loathsome self-image, Dorian slashes that portrait. He is found by servants. “Lying on the floor was a dead man, in evening dress, with a knife in his heart. He was withered, wrinkled and loathsome of visage. It was not till they examined the rings that they recognised who it was.”

Friday, 16 June 2023

Fallacies of Capitalism 12: The Lump of Labour Fallacy

The Lump of Labour Fallacy

The lump of labor fallacy is a mistaken belief that there is only a fixed amount of work or jobs available in an economy. It suggests that if someone gains employment or works fewer hours, it must mean that someone else loses a job or remains unemployed. However, this idea is flawed.

Here's a simple explanation:

- Fixed Pie Fallacy: Imagine a pie that represents all the available work in the economy. The lump of labor fallacy assumes that the pie is fixed, and if one person takes a larger slice (more work), there will be less left for others. This assumption overlooks the potential for economic growth and the creation of new opportunities.

Example: "Assuming that there is only a fixed amount of work available is like believing that the pie will never grow bigger, even when more bakers join the kitchen."

- Technological Advancements: Technological progress often leads to increased productivity and efficiency. While it may replace certain jobs, it also creates new ones. The lump of labor fallacy fails to account for the dynamic nature of the job market and how innovation can generate fresh employment opportunities.

Example: "When ATMs were introduced, people worried that bank tellers would become jobless. However, the technology not only made banking more convenient but also led to the emergence of new roles in customer service and technology maintenance."

- Changing Demand and Specialization: Economic shifts and changes in consumer preferences continually reshape the job market. As demand for certain products or services diminishes, it opens up avenues for new industries and occupations to thrive. The lump of labor fallacy overlooks this adaptive nature of economies.

Example: "When the demand for typewriters declined, many feared that typists would become unemployed. However, the rise of computers and the internet created a surge in demand for IT specialists and web developers."

In summary, the lump of labor fallacy wrongly assumes that there is a limited amount of work available, failing to consider factors like economic growth, technological advancements, and changing market demands. By understanding the dynamic nature of economies, we can see that job opportunities can expand and transform rather than being fixed or limited.

Wednesday, 13 July 2022

Thursday, 18 March 2021

Thursday, 24 December 2020

Covid prompts a new approach to economic growth

An FT Editorial

The coronavirus pandemic means that 2020 will go down in history as the year with one of the deepest plunges in national income on record. In the UK, which has one of the longest continuous logs of economic output, gross domestic product looks likely to have fallen around a tenth this year, making for the biggest recession in three centuries. Yet even these figures, however eye-watering, do not capture the true collapse in wellbeing, which must be the ultimate goal of economic policy.

In theory, gross domestic product adds up everything that a country produces in one year. The fall in national income during 2020 is easy to explain: interruptions to normal economic activity have meant that far less has been produced. In this regard the drop in gross domestic product will capture some of the missed outings and trips to the cinema, the cancelled holidays and all the meals and drinks with friends that had to be postponed.

There is, however, plenty that the figures miss. To aggregate the value of very different activities that take place in an economy statisticians use market prices — allowing them to compare the production of both apples and oranges on a common scale. But the absence of these prices for much of healthcare and education in many countries — statisticians merely impute their production from how much the government spends on them — means the disruptions to schools and delays in administering non-coronavirus medical care is missed. Spending on healthcare might have risen but on a net basis societies got far less for their money.

On the other hand, public parks and other green spaces have become much more important but their contribution to the economy will not be registered as part of GDP. Unpaid labour too, those who tried to teach their children at home, sewed personal protective equipment or baked banana bread, will not appear in the story of the year told by national income figures. Nor will the drop in air pollution or the volunteers who took care of neighbours.

Even an accurate counting of the drop in production this year would still miss the psychological damage done by prolonged isolation and loneliness; the “hidden pandemic” of mental health problems. That suggests the solution would not be to expand the definition of gross domestic product to include the production it misses but to consider focusing on wellbeing directly.

All the same, the experience of this year — when governments shut down their economies in order to protect public health — has shown that economic growth has not been prioritised above all else. Already, a wider definition of wellbeing than a pure economic one is implicitly being used to inform policy. Daily count cases and death rates have played a much bigger role in policymaking than quarterly growth figures. Suggestions that health measures represent a trade-off with economic fortunes have also been overplayed. The best way of protecting jobs this year has been keeping the virus under control: New Zealand, which managed to remain virtually virus-free thanks to an early and strict lockdown, is reaping the economic rewards.

This will remain true when the pandemic has passed. A healthy and well-educated workforce is one of the most important prerequisites to growth and secure, well-paid, high quality jobs are among the best foundations to protect mental wellbeing. Unemployment and poor-quality work can easily destroy people’s sense of self-worth while a robust private sector is essential to provide the tax revenues for health and education. The goal should be to create the kind of society where economic growth and wellbeing go hand in hand.

Thursday, 20 September 2018

Let’s face it. Our university factory has failed to deliver on its promises

In any other area it would be called mis-selling. Given the sheer numbers of those duped, a scandal would erupt and the guilty parties would be forced to make amends. In this case, they’d include some of the most eminent politicians in Britain.

But we don’t call it mis-selling. We refer to it instead as “going to uni”. Over the next few days, about half a million people will start as full-time undergraduates. Perhaps your child will be among them, bearing matching Ikea crockery and a fleeting resolve to call home every week.

They are making one of the biggest purchases of their lives, shelling out more on tuition fees and living expenses than one might on a sleek new Mercedes, or a deposit on a London flat. Many will emerge with a costly degree that fulfils few of the promises made in those glossy prospectuses. If mis-selling is the flogging of a pricey product with not a jot of concern about its suitability for the buyer, then that is how the establishment in politics and in higher education now treat university degrees. The result is that tens of thousands of young graduates begin their careers having already been swindled as soundly as the millions whose credit card companies foisted useless payment protection insurance on them.

Rather than jumping through hoop after hoop of exams and qualifications, they’d have been better off with parents owning a home in London. That way, they’d have had somewhere to stay during internships and then a source of equity with which to buy their first home – because ours is an era that preaches social mobility, even while practising a historic concentration of wealth. Our new graduates will learn that the hard way.

To say as much amounts to whistling in the wind. With an annual income of £33bn, universities in the UK are big business, and a large lobby group. They are perhaps the only industry whose growth has been explicitly mandated by prime ministers of all stripes, from Tony Blair to Theresa May. It was Blair who fed the university sector its first steroids, by pledging that half of all young Britons would go into higher education. That sweeping target was set with little regard for the individual needs of teenagers – how could it be? Sub-prime brokers in Florida were more exacting over their clients’ circumstances. It was based instead on two promises that have turned out to be hollow.

Promise number one was that degrees mean inevitably bigger salaries. This was a way of selling tuition fees to voters. Blair’s education secretary, David Blunkett, asked: “Why should it be the woman getting up at 5 o’clock to do a cleaning job who pays for the privileges of those earning a higher income while they make no contribution towards it?” When David Cameron’s lot wanted to jack up fees, they claimed a degree was a “phenomenal investment”.

Both parties have marketed higher education as if it were some tat on a television shopping channel. Across Europe, from Germany to Greece, including Scotland, university education is considered a public good and is either free or cheap to students. Graduates in England, however, are lumbered with some of the highest student debt in the world.

Yet shove more and more students through university and into the workforce and – hey presto! – the wage premium they command will inevitably drop. Research shows that male graduates of 23 universities still earn less on average than non-graduates a whole decade after going into the workforce.

Britain manufactures graduates by the tonne, but it doesn’t produce nearly enough graduate-level jobs. Nearly half of all graduates languish in jobs that don’t require graduate skills, according to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. In 1979, only 3.5% of new bank and post office clerks had a degree; today it is 35% – to do a job that often pays little more than the minimum wage.

Promise number two was that expanding higher education would break down class barriers. Wrong again. At the top universities that serve as gatekeepers to the top jobs, Oxbridge, Durham, Imperial and others, private school pupils comprise anywhere up to 40% of the intake. Yet only 7% of children go to private school.Factor in part-time and mature students, and the numbers from disadvantaged backgrounds are actually dropping. Nor does university close the class gap: Institute for Fiscal Studies research shows that even among those doing the same subject at the same university, rich students go on to earn an average of 10% more each year, every year, than those from poor families.

Far from providing opportunity for all, higher education is itself becoming a test lab for Britain’s new inequality. Consider today’s degree factory: a place where students pay dearly to be taught by some lecturer paid by the hour, commuting between three campuses, yet whose annual earnings may not amount to £9,000 a year – while a cadre of university management rake in astronomical sums.

Thus is the template set for the world of work. Can’t find an internship in politics or the media in London that pays a wage? That will cost you more than £1,000 a month in travel and rent. Want to buy your first home? In the mid-80s, 62% of adults under 35 living in the south-east owned their own home. That has now fallen to 32%. Needless to say, the best way to own your own home is to have parents rich enough to help you out.

Over the past four decades, British governments have relentlessly pushed the virtues of skilling up and getting on. Yet today wealth in Britain is so concentrated that the head of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, Paul Johnson, believes “inheritance is probably the most crucial factor in determining a person’s overall wealth since Victorian times”.

Margaret Thatcher’s acolytes promised to create a classless society, and they were quite right: Britain is instead becoming a caste society, one in which where you were born determines ever more where you end up.

For two decades, Westminster has used universities as its magic answer for social mobility. Ministers did so with the connivance of highly paid vice-chancellors, and in the process they have trashed much of what was good about British higher education. What should be sites for speculative inquiry and critical thinking have instead turned into businesses that speculate on property deals, criticise academics who aren’t publishing in the right journals – and fail spectacularly to engage with the serious social and economic problems that confront the UK right now. As for the graduates, they largely wind up taking the same place in the queue as their parents – only this time with an expensive certificate detailing their newfound expertise.

For everyone’s sake, let us declare this experiment a failure. It is high time that higher education was treated again as a public good, as Jeremy Corbyn recognises with his pledge to scrap tuition fees. But Labour also needs to expand vocational education. And if it really wants to increase social mobility and reduce unfairness, it will need to come up with tax policies fit for the age of inheritance.

Sunday, 20 May 2018

Thursday, 16 November 2017

Why Brexit Britain needs to upskill its workforce

A British hospital director told me he was hunting for staff to replace foreign doctors and nurses leaving because of Brexit. He hadn’t found many qualified Britons queuing to replace them. In fact, he specified: “Not one!”

Friday, 27 October 2017

My fantasy Corbyn speech: ‘I can no longer go along with a ruinous Brexit’

Last week I wrote a speech for Theresa May, which concluded with an announcement that she had decided Brexit was impossible to deliver. Sadly she didn’t listen, and so onwards she leads us towards the cliff edge. I am hoping for better luck with Jeremy Corbyn, fantasising that he delivers this speech to a rally of his faithful Momentum followers …

“Thank you for that wonderful reception. Yes, yes, I know my name. ‘Oh Jeremy Corbyn’. Yes, that’s me. Now please stop singing and sit down. Please.

“I will be honest with you. I didn’t want the job. I didn’t think I would get the job. I wasn’t sure I could do the job. But thanks to you I got it. Thanks to you I now have the confidence to do it. I approach the challenge of being prime minister not with fear or trepidation but with confidence that our time is coming. That it is our duty now to serve. Protest is one thing. Government is another. And we must now prepare, genuinely prepare, as a government in waiting.

“If I become prime minister it is Brexit that will define my leadership. As a result of what happened on 23 June 2016 I have no choice in the matter. The people’s choice dictates that it is so.

I have concluded that rejecting this vision of Brexit is the only route to the vision of the world that drives us

“It is clear to me the constructive ambiguity of our position on Brexit is no longer tenable. It is fine for a party of protest. It is not good enough for a party one step away from government.

“Let’s imagine this entirely credible scenario. As the current chaos inside the government continues, Mrs May falls. The Tories try to foist another prime minister on us, chosen by their ageing membership. But we and the public won’t wear it. We force an election. We win an election. I am prime minister. Now the hard part begins.

“What does our ‘jobs-first’ Brexit mean then, in power? What is a jobs-first Brexit if our leaving the single market hurts growth, as every analysis in the world says it will? What is a jobs-first Brexit dependent on trade if trade slows and even grinds to a halt with the absence of a proper customs infrastructure at our ports, the absence of good trade deals not just with the EU but with the 66 countries with whom we have deals as part of the EU? What is a jobs-first Brexit if firms decide that if the UK leaves the EU, they leave the UK, and take their jobs and their tax take with them?

“And how can we fund all the things in our election manifesto that we need and want to fund in the future if our economy tanks?

“At Labour’s party conference, I said that our continued membership of the EU would prevent us from implementing many of the plans in our manifesto. I am grateful to the New European, which sought legal advice in Brussels and established this was not the case. So the question becomes, not ‘What do we lose by staying in?’, but ‘What do we lose by coming out?’

“The dominance of the hard right is clear in their pressing Mrs May to walk away from the negotiations, crash out of the EU, into the World Trade Organisation. I am of the internationalist left. We exist to fight the nationalist right, not to dance to its tune. We believe in support for the many, not the prosperity of the few. It is the nationalist right that is leading the Brexit Mrs May is pursuing, whatever the cost. It is their only route to the vision of the world that drives them. And, today I want to tell you – I have concluded that rejecting this vision of Brexit is the only route to the vision of the world that drives us. In this debate, they are the reactionaries, we and the Europeans the progressives.

“Take back control, they said. But what kind of control? Their control. Their right to dump decades of law with their ‘great repeal bill’, and bring about their vision of a low-tax, low-regulation economy, public services there for profit not public, employment and environmental rights shredded, one of the great powers of the world reduced to a gigantic Cayman Islands. That is their dream. And many of those who voted for Brexit, in the poorest areas, the places we represent, they will be the hardest hit. As the reality of power nears, I must tell you, candidly, that I can no longer go along with it. Not now. Not in two years. Not ever.

“No deal, I must warn you, would be a catastrophe. So if Mrs May is still prime minister, and presents the no-deal option to parliament, be in no doubt – we will vote against it. We will press for a deal with keeps us in the single market and the customs union, to protect trade and avoid chaos.

“But today I want to go further. The referendum was close. It was not, contrary to the claims of the Brextremists, ‘clear’, let alone ‘overwhelming’. Millions are deeply concerned about what is happening to our country. I believe people have a right to change their minds as this all unfolds. And politicians have a duty to reflect that, and to give proper vent to the debate it represents.

“Democracy is a process, not a moment in time. If the government falls, and we win an election, then we can put a different vision of Brexit to the country, and we will. If we can bring about a fresh election, this is the Brexit policy you will be voting for.

“We will take over the negotiations from Mrs May and her hapless, hopeless team. We will review what progress has been made and assess whether Brexit can be delivered on the timescale set out under the article 50 process she triggered.

“If we conclude, as on any current assessment seems likely, that Brexit cannot be delivered without real damage to our economy, that a jobs-first Brexit is impossible, that it will mean lower growth, higher prices, higher unemployment, more austerity, cuts to public services, customs chaos, the return of a hard border in Ireland and the potential undoing of the Good Friday agreement, the loss of security cooperation with our partners, then I will revoke article 50.

“I am clear that a referendum decision can only be overturned by another one, and so we will legislate for a new referendum, and the choice we will put before the British people is between staying in, or leaving on the terms then on offer.

“If, as I believe they will, the British people opt to reverse their decision of last June, that will put us in a strong position then to succeed where David Cameron failed, and win the argument for a reformed EU that works for all.

“Comrades, this has been a lot to take in. But I believe it is the right course for our party, for our movement, and most important of all, for the country.

“This is our country too. This is our time. Let’s take back control of our destiny, and build a country future generations will be proud to call home. Thank you.”

Wednesday, 4 October 2017

Yashwant Sinha - The BJP will be held to account in 2019

Tuesday, 20 December 2016

The Problem is Free Trade not Free Movement

While freedom of movement has been a hot topic since the debates around Brexit began, few would have predicted it would become such a focus in the Unite general secretary election, in which I’m standing.

Anger around jobs and conditions is justified, but often misdirected. Neoliberal capitalism has been disastrous. Free trade deals enshrine the rights of capital while ignoring the needs of humans and our warming planet. Workers have been dumped out of jobs by the million, work has intensified, workers feel more vulnerable to managerial whim, the share of wealth going to wages has fallen, welfare systems have been slashed and huge areas of life – including education, health and housing – are increasingly commoditised, all while our limited democracy is increasingly hollowed out.

Migrants are prime scapegoats for many politicians and media. Some employers provide fertile material for racists and nationalists. Fujitsu, my own employer, proposes to cut 1,800 UK jobs, hoping to boost profits by offshoring jobs to low-paid countries. Fujitsu is even asking some workers to train their replacements, brought to the UK to learn the job. Workers are being asked to dig their own graves.

When our livelihoods are threatened, workers sometimes respond by claiming privileged access to jobs, housing, and so on, and excluding others on the basis of gender, race or nationality. This is tempting because it sometimes “works” for some people for a short time. But it is misguided. If some workers try to protect their interests at the expense of others, the unity we need to win is undermined and we all lose.

Gerard Coyne is also standing for the general secretary post and his silence on this question, as on so many others, is deafening; meanwhile his relationships with the Labour right are worrying.

Len McCluskey, the present general secretary, though anti-racist, has fudged on workers’ freedom of movement, wrongly conceding ground to racists and nationalists. Just before the EU referendum McCluskey referred to it as an experiment at UK workers’ expense. As a delegate to the Unite conference shortly after the referendum, I moved a motion defending freedom of movement. Unite’s leadership opposed it, with their own motion calling for debate on the question. McCluskey now boasts that he has led this debate “demanding safeguards for workers, communities and industries affected by migration policy driven by greedy bosses”. Beyond dog-whistle politics, what does this mean?

McCluskey explained in a speech for the thinktank Class (Centre for Labour and Social Studies) that his “proposal is that any employer wishing to recruit labour abroad can only do so if they are either covered by a proper trade union agreement, or by sectoral collective bargaining”. All jobs should be covered by union agreements, but union weakness means most are not, and this applies especially to industries in which migrants have to work.

What would McCluskey’s proposal mean in practice? What would count as recruiting abroad? How long would a worker have to be in the UK before they could apply for an un-unionised job?

Giving different rights to different workers based on their nationality is discriminatory and divisive. It undermines solidarity. Blocking employers hiring on the basis of nationality would repeat the mistake of some trade unionists of a previous generation who sought to control the labour supply by excluding women from some jobs, fearing “they” would push down “our” wages. We, Unite’s membership, like the working class as a whole, come from all over the world. This is a strength, not a weakness.

It is free trade, not free movement of people, that has been a disaster for working-class people. Manufacturing has seen colossal job losses in recent decades as production has moved to countries in the south and east. Too often unions have responded by making common cause with the very employers sacking their members, against the foreign competition.

This approach has failed to protect jobs. Whether it is an employer threatening to dismiss and re-engage the same workers on lower pay (like the Durham teaching assistants), replacing workers with cheaper ones in the same workplace, or moving the jobs halfway round the world, workers are right to fight the degradation of employment. You can’t do that in partnership with the employer who is sacking you.

Thankfully workers are not always paralysed by the confusion of their leaders. Unite members at Capita and Prudential won important victories against offshoring. Members at the Fawley oil refinery spurned British Jobs For British Workers slogans and built solidarity to win equal pay for workers of all nationalities instead of trying to restrict the employment of migrants. Inspired by the Prudential win, industrial action in my own workplace currently includes refusal to cooperate with projects to move work offshore.

Unions should be following Fawley workers in demanding everyone is paid the rate for the job, regardless of employer, employment status, or nationality. We should be demanding full pay transparency, monitored by the unions. We should be calling for all jobs to be openly advertised, with no discrimination in hiring based on nationality. And existing workers should refuse to cooperate with handing over work unless their employment is assured.

The labour movement needs to regain the confidence to demand solutions that meet human needs, even when that upsets big business. We won’t do that by turning workers against each other on nationalist grounds, or by fudging the issue.

No general secretary candidate should chase votes by undermining the unity members need to defend their jobs. I am calling on Len McCluskey and Gerard Coyne to join me in championing workers’ rights to move freely (not just within the EU) and opposing any employment restrictions based on nationality.

Tuesday, 6 September 2016

Does the left have a future?

by John Harris in The Guardian

There is more than one spectre haunting modern Europe: terrorism, the revival of the far right, the instability of Turkey, the fracturing of the EU project. And in mainstream politics, all across the continent, the traditional parties of the left are in crisis.

In Germany, the Social Democratic party, once a titanic party of government, has fallen below 20% in the national polls. In France, François Hollande’s ratings hover at around 15%, while the Spanish Socialist Workers’ party has seen its support almost halve in less than a decade.

The decline of Greece’s main social democratic party, which fell from winning elections to under 5% in less than a decade, was so rapid that it spawned a new word, “pasokification”, for the collapse of traditional centre-left parties. Even in Scandinavia, once-invincible parties of social democracy have been hit by increasingly disaffected voters, as rightwing populists stoke anxiety about immigration and its impact on the welfare state.

The reinvention of left politics in the countries most harshly affected by the Eurozone crisis might appear to offer grounds for new optimism. In Spain, Podemos rages against the political establishment it calls “la casta”, while Greece has seen the rise of Syriza, the upstart radical party that has been in government since 2015. The energy and iconoclasm of these two movements finds echoes elsewhere – witness the unexpected wave of support in the US for the Bernie Sanders campaign. But beyond the torrid Greek experience, these developments still feel more like an expression of protest and dissent than a sign of the imminent acquisition of power.

In Britain, the Labour party embodies almost all of the crises of the modern left. Labour still does well in big cities such as London, Bristol, Leeds and Manchester, but flounders in the south and east of England. The party may also be losing its hold on its old industrial heartlands, and in Scotland it looks headed for extinction. Labour’s poll ratings have been stuck in the same lowly place since before 2010.

This is not fundamentally about the party’s current internal strife. Labour is engulfed by the same crisis facing its sister parties in Europe. Political commentary tends to focus on politicians, and describe the world as if parties can be pulled here and there by the sheer will of powerful individuals. But Labour’s problems are systemic, rooted in the deepest structures of the economy and society. The left’s basic ideals of equality, solidarity and a protected public realm should be ageless. But everything on which it once built its strength has either disappeared, or is shrinking fast.

The western left faces three grave challenges, which strike at the heart of its historic sense of what it is and who it speaks for. First, traditional work – and the left’s sacred notion of “the worker” – is fading, as people struggle through a new era of temporary jobs and rising self-employment, which may soon be succeeded by a drastic new age of automation. Second, there is a new wave of opposition to globalisation, led by forces on the right, which emphasise place and belonging, and a mistrust of outsiders. And all the time, politics rapidly fragments, which leaves the idea that one single party or ideology can represent a majority of people looking like a relic. The 20th century, in other words, really is over. Whether the left can return to meaningful power in the 21st is a question currently surrounded by a profound sense of doubt.

On the morning of May 8 2005, Tony Blair stood on the steps of Downing Street, after an unprecedented third consecutive Labour election victory. On the face of it, this provided proof of Labour’s newfound dominance, and another occasion for union jacks, talk of a new dawn, and the same blithe optimism that had carried Blair to power in 1997. But this time he took a much more hard-headed stance. Labour had just been been re-elected on 35.2% of the vote, with the support of only 22% of the electorate. The first-past-the-post system had worked its strange magic and taken the party back into government – but on the lowest figures for any government in the democratic age.

That day, Blair seemed contrite. “I’ve listened and I’ve learned, and I think I’ve a very clear idea what the people now expect from the government in a third term,” he said. “And I want to say to them very directly that I, we, the government, are going to focus relentlessly now on the priorities that people have set for us.” He spoke of the idea that “life is still a real struggle for many people”, and devoted one section of his speech to rising public angst about immigration.

Five months later, Blair made his 12th annual conference speech as party leader, and all traces of humility had vanished. His essential message reflected one of the key strands of his political theology: the mercurial magic of modern capitalism, and his mission to toughen up the country in response to the endless challenges of the free market. “Change is marching on again,” he announced, in that messianic tone that had begun to emerge in his speeches around the time of 9/11. “The pace of change can either overwhelm us, or make our lives better and our country stronger,” he went on. “What we can’t do is pretend it is not happening. I hear people say we have to stop and debate globalisation. You might as well debate whether autumn should follow summer.”

His next passage was positively evangelistic. “The character of this changing world is indifferent to tradition. Unforgiving of frailty. No respecter of past reputations. It has no custom and practice. It is replete with opportunities, but they only go to those swift to adapt, slow to complain, open, willing and able to change.”

I watched that speech on a huge screen in the conference exhibition area. And I recall thinking: “Most people are not like that.” The words rattled around my head: “Swift to adapt, slow to complain, open, willing and able to change.” And I wondered that if these were the qualities now demanded of millions of Britons, what would happen if they failed the test?

Listening to Blair describe his vision of the future – in which one’s duty was to get as educated as possible, before working like hell and frantically trying not to sink – I was struck by two things. First, the complete absence of any empathetic, human element (he mentioned the balance between life and work, but could only offer “affordable, wraparound childcare between the hours of 8am-6pm for all who need it”), and second, the sense that more than ever, I had no understanding of what values the modern Labour party stood for.

If modern capitalism was now a byword for insecurity and inequality, Labour’s response increasingly sounded like a Darwinian demand for people to accept that change, and do their best to ensure that they kept up. Worse still, those exacting demands were being made by a new clique of Labour politicians who were culturally distant from their supposed “core” voters, and fatally unaware of their rising disaffection.

In 2010, under Gordon Brown’s butter-fingered leadership, Labour fell to a miserable 29% of the vote – its lowest share since 1983, when it came within a whisker of finishing third. Five years later, despite opinion polls suggesting a possible Labour win, Ed Miliband could only raise Labour’s vote share by a single percentage point.

If the party hoped to reassemble the electoral coalition that had just about held together through the second half of the 20th century, the world that gave rise to it had clearly gone. Trade union membership was at an all-time low, heavy industry had disappeared, and traditional class consciousness had waned.

As those foundations crumbled, so did the party’s old nostrums of nationalisation and redistribution. In their place, and in unbelievably favourable circumstances that veiled Labour’s underlying weaknesses – a long economic boom, and a Conservative party incapable of coherence, let alone power – Blair and Brown had come up with a thin social democracy that stoked the risk-taking of the City and used the proceeds to spend huge amounts of money on public services. But the financial crisis had put an end to that model as well.

Meanwhile, as deindustrialisation ripped through 20th-century economies, the instability and fragmentation embodied by the financial and service sectors was taken to its logical conclusion by new digital businesses. In turn, the latter have spawned what some now call “platform capitalism”: a model whereby goods, services and labour can be rapidly exchanged between people, companies and multinational corporations – think of Uber, eBay, Airbnb or TaskRabbit, which link up freelance workers with people who need help with such tasks as cleaning, deliveries or moving home – with little need for any intermediate organisations. This has not only marginalised retailers and wholesalers. It calls into question the traditional role of trade unions, and further reduces the power of the state, which is now locked into a pattern where innovations take rapid flight and it cannot keep up.

In retrospect, the left’s halcyon era was based on a straightforward project. When the archetypal factory gates swung open, out came thousands of men – and by and large, they were men – united by an unchanging daily experience, and ready to support a political force that would use the unions, the state, and the fabled “mass party” to create a new, much fairer world in their monolithic image.

Now, an atomising, quicksilver economy bypasses those structures, and has fragmented people and places so thoroughly that assembling meaningful political coalitions has begun to appear almost impossible. These are the social and political conditions that define relatively prosperous places such as the commuter towns of Surrey, or Essex, the centres of the knowledge economy to be found around Cambridge, and the gleaming new town of Livingston in Scotland. And in a very different way, these new conditions can be experienced just as powerfully in the tracts of the UK that modernity seems to have left behind.

In the spring of 2013, a couple of days after the death of Margaret Thatcher, the Guardian dispatched me to the post-industrial south Wales town of Merthyr Tydfil, to talk to people about the legacy of her time in power. I had been there many times before, and always beheld a place in which Labour’s decline was not a matter of symbolism and metaphor, but something to be directly experienced.

Essentially, it is a place defined by absences: of the coal and steel industries, and the huge Hoover factory that closed in 2009 – but more generally, of the ideas and institutions that once defined the Labour party and the wider Labour movement. Between 1900 and 1915, Merthyr was represented in the House of Commons by Keir Hardie, Labour’s first leader and founding icon. In 1997, the party received an astonishing 77% of the vote in the town. But by 2010, that figure had crashed to 44%, as local politics belatedly reflected a lingering sense of dismay and loss that dated back to the defeat of the miners’ strike in 1985.

As I drove into town, I clocked an EE call centre, which pays its customer services operatives around £16,000 a year. Outside the town’s vast Tesco, I spoke to two retired men, who understood what had happened to Merthyr as a kind of offence to their basic values. In the past, one of them told me, “a man wanted to be a working man: he didn’t want to be in here, stacking shelves”. When I asked him about the legacy of the miners’ strike, what he said was full of pathos and tragedy. “Thirty years ago, whatever … it’s still embedded in us down here, he said. “We still talk about it every day: what might have happened if it had gone the other way.”

In the town centre, I then met an 18-year-old who was finding it impossible to get a job. “I’ve applied and applied, and it’s all been declined,” she said. She wondered whether there was something wrong with her CV: the idea that there were perhaps larger forces to blame for her predicament did not enter the conversation. I wondered, did she know what a trade union was? “No,” she said. “I don’t. What’s that?”

One in seven Britons is now self-employed. In the US, Forbes magazine has predicted that by 2020, 50% of people will at least partly work on a freelance basis. In 2015, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development reported that since 1995, “non-standard” jobs – which is to say, temporary, part-time or self-employed positions – accounted for the whole of net jobs growth in the UK since 1995.

Such is the rise of the so-called “gig economy”. Economists and sociologists talk about “the precariat”, a growing part of the population for whom work is not the basis of personal identity, but an on-off part of life from which they often need protection. Some of this, of course, is down to the venality and greed of businesses. But the central momentum behind it is rooted in technology, and what Marxists would call the “mode of production”. In a world in which businesses can survey their order books on an hourly basis and temporarily hire staff at the touch of a button, why would they base their arrangements on agreements that last for years?

Merthyr is still said to be a Labour heartland. But like so many other places, it is brimming with a sense of a politics now hopelessly out of time: older people whose sense of a meaningful Labour identity is tangled up in an increasingly distant past, and younger residents who know nothing of any of this, and have little sense of the relevance of politics to their lives. In Merthyr, 56% of voters supported Brexit; at the Welsh assembly elections of 2016, Ukip won 20% of the local vote. In such places, the sense of Labour’s fall is palpable.

Go to any traditional Labour area, and people will tell you that Labour was once “the party of the working man”. Even now, from its name onwards, this reductive understanding of Labour, its people and its essential mission still runs deep, not least within the party itself. In place of “the working man”, the New Labour years ushered in a politics pitched at “hard-working families”, a term partly intended to reflect people’s increasing antipathy towards people on benefits. Even when it was advocating enhancements to childcare and pre-school provision, Labour tended to do so in terms of getting new mothers back into paid employment as soon as possible.

Today’s Labour party has not shed these outmoded ideas about the nature of work. Both Owen Smith and Jeremy Corbyn have sketched utopian plans to somehow magic the world back to some unspecified time before 1980. Smith wants to revive the Ministry of Labour, done away with by Harold Wilson’s Labour government in 1968. Corbyn’s “10-point plan to rebuild and transform Britain” is all about “full employment and an economy that works for all”, and promises to restore “security to the workplace”. These visions are either naive or dishonest, but they reflect delusions that run throughout Labour and the left.

In a world in which work is changing radically, modern Conservatism applauds these shifts. For clued-up Tories, it is time to rebrand as “the workers’ party” – in which the worker is a totem of rugged individualism, not a symbol of solidarity. For proof, read Britannia Unchained, a breathless treatise about economics and the future of Britain co-authored by five Tory MPs who entered parliament in 2010: Kwasi Kwarteng, the new international development secretary Priti Patel, Dominic Raab, Chris Skidmore and Elizabeth Truss, who Theresa May appointed justice secretary in her first reshuffle. According to Britannia Unchained, the ideal modern worker is represented by the drivers who work for the London cab company Addison Lee. These people “work on a freelance basis. They can net £600 a week in take-home pay. But they have to work for it – up to 60 hours a week.” In this vision – taken to its logical conclusion by Uber – the acceptance of insecurity becomes a matter of heroism, and a new political division arises between the grafters and those – as Britannia Unchained witheringly puts it – “who enjoy public subsidies”. In other words, the “skivers” versus the “strivers”.

Blair tried to lead New Labour in this direction, but his attempts always jarred against his party’s ingrained support for the traditional welfare state and its attachment to increasingly old-fashioned ideas of secure employment. But in the context of the modern labour market, lionising work for its own sake will never bolster support for a politics built on those values. Instead, it may push people to the right.

People who work, after all, are no longer part of a monolithic mass: many increasingly think of themselves as lone agents, competing with others in much the same way that companies and corporations do. In the build-up to the 2015 election, I saw vivid proof of how fundamentally this erodes the left’s old understanding of its bond with its supporters.

In Plymouth, I watched a woman answer the door to a Labour canvasser with the words: “I’m a grafter – you ain’t doing nothing for me.” I spoke to a man in the north-eastern steeltown of Redcar who told me he would never vote Labour “because I work”. In the bellwether seat of Nuneaton, two women told me that Ed Miliband would probably win the election because “all the people on benefits” were going to vote for him. As these people saw it, Labour was no longer the “party of work”.

This is a hell of a knot to untangle. But for the left, a solution might begin with the understanding of an epochal shift that pushed politics beyond the workplace and the economy into the sphere of private life – a transition first articulated by feminism, with the assertion that “the personal is political”.

Belatedly building this insight into left politics does not entail a move away from the kind of regulation and intervention that might make modern working lives much more bearable, nor from the idea that government might foster more rewarding and useful work, chiefly via investment and education.

The deep changes wrought by our ageing society will anyway begin to increase the numbers of people beyond working age, and accelerate the shift away from paid work towards caring. But the most radical shift will be caused by automation and its effects on employment. If the Bank of England now reckons that as many as 15m British jobs are under threat from technology, and if a third of jobs in the retail sector are predicted to disappear by 2025, does the myopic, often macho rhetoric of work and the worker really articulate any meaningful vision?

The left naturally embraced the mantra of the Occupy movement – the glaring division between the super rich and the rest of us embodied by the slogan “We are the 99%”. Objectively, the idea of a division between a tiny, light-footed international elite and everybody else holds true. But in everyday life, this division finds little expression.

Instead, the rising inequality fostered by globalisation and free-market economics manifests itself in a cultural gap that is tearing the left’s traditional constituency in two. Once, social democracy – or, if you prefer, democratic socialism – was built on the support of both the progressive middle class and the parts of the working class who were represented by the unions. Now, a comfortable, culturally confident constituency seems to stare in bafflement at an increasingly resentful part of the traditionally Labour-supporting working class.

The first group has an internationalised culture, a belief in what the modern vernacular calls diversity, and the confidence that comes with education and relative affluence. It can apparently cope with its version of job insecurity (think the freelance software developer, rather than the warehouse worker on a zero-hours contract). But on the other side are people who have a much more negative view of globalisation and modernity – and in particular, the large-scale movement of people. In the UK, they tend to live in the places that have largely voted Labour but supported leaving the EU, and whose loudest response to globalisation is to re-embrace precisely the “custom and practice”, as Blair put it, that modern economies tend to squash: to emphasise place and belonging, and assert an essentially defensive national identity.

Does anyone on the left want to write off the working-class voters who chose Brexit as a mass of bigots and racists?

From a sympathetic perspective, to put out a flag can be a gesture way beyond mere jingoism. It often stands as an assertion of esteem – and collective esteem, at that – in an insecure, unstable world that frequently seems to deny people any at all. Those who were once coalminers or steelworkers may now be temporarily-employed “operatives” waiting for word of that week’s working hours. In a cultural sense, by contrast, national identity offers people at least some prospect of regaining a sense of who they are, and why that represents something important. Even when it comes to resentments around immigration, a nuanced, empathetic understanding should not be beyond anyone’s grasp: people can be disorientated by rapid population change and anxious to assert a sense of place without such feelings turning hateful.

There is also a much nastier side to all this – a surge in racism, which has happened all over Europe, and appears to have been given grim licence by the Brexit vote. Even so, does anyone on the left want to write off the 3.8m people who voted for Ukip in 2012 – or the even larger number of working-class voters who chose Brexit – as a mass of bigots and racists? Even in its most unpleasant manifestations, most prejudice has a wider context, and it is clear that these modern antipathies are most keenly felt in places that have either been left behind by modernity, or represent its most difficult elements: insecure job markets, scarce housing, overstretched public services.

I have met enough people who have identified themselves as “English” to know that it is usually not just a matter of national pride. It also tends to translate as a set of defiant cultural rejections, on the part of people who are not middle-class, not from London, and angry about the way that people who fit both those descriptions view the rest of the country. The UK census of 2011 was the first ever to include a question about national identity – and in England, 60% of people described themselves as English only. But the left, in Britain as much as in Europe, remains in denial about why people have taken refuge in such expressions of nationhood. This is something that applies to both so-called “Blairites”, and Corbyn and his supporters: one is so enraptured by globalisation that it thinks of vocal expressions of patriotism as a retrogressive block on progress; the other cleaves to a rose-tinted internationalism that regards such things as a facade for bigotry.

In 2014, I spent three days in and around the Kent coast, following Ukip activists, and talking to people watching their manoeuvres. In the town of Broadstairs, a group of energetic leftwing activists – who would go on to found a thriving local branch of the pro-Corbyn group Momentum – had organised a day of campaigning against Ukip, focused on Nigel Farage’s candidacy in the seat of South Thanet. I watched them debate with a man sitting on the town’s seafront, who was determined to vote for Farage, and scornful of their attempts to dissuade him.

“He’s going to be voted in, and there’s nothing you people can do about it,” he said, gesturing to them with a kind of camp contempt.

He then explained his main source of anger. His son, he said, had a speech disability, and could not find work in his chosen field of catering. “Nobody will give him a job. But a foreigner could come over here and speak not one word of English and they get a job.”

The truth of this was batted around for two or three minutes, before he came to his conclusion. “I’m brassed off,” he said, and he then spoke pointedly about his own sense of insecurity. “I’m a working man. I’ve paid all my taxes and everything. And if anything goes wrong with me or my family and I get thrown out of my house because I can’t pay my mortgage, I’ll get put in a bedsit.”

What, then, did he want? “A better England,” he said, and I could instantly sense that he had a basic set of grievances – about insecurity and unfairness – to which the political left would once have been able to confidently speak. Unfortunately, in the absence of any meaningful cultural bonds, the avowedly leftwing people to whom he was talking were residents of a completely different reality.

Can things be any different? If left politics is not to shrink into a metropolitan shadow of itself and abandon hope of gaining national power, they have to. Indeed, if British politics is not to speed towards the kind of nasty populism taking root all over Europe and calling the shots in such countries as Poland and Hungary, this is a matter of urgency – not least because as automation takes hold, the disorientation on which the new rightwing politics feeds will only increase.

Scotland is perhaps instructive. The Scottish National party’s essential triumph has been to bond with millions of people via a modern, “civic” kind of nationhood, and thereby recast a social democratic model of government in terms of identity and belonging – rather than standing on the other side of a cultural divide, as Labour now does in England. To some extent, this is a matter of clever branding, and the successive political feats pulled off by Alex Salmond and Nicola Sturgeon: the lion’s share of SNP MPs and MSPs are almost as metropolitan and media-savvy as the scions of New Labour were. But for the time being, it undoubtedly works.

South of the border, by contrast, a key part of Labour’s crisis is that it so clearly fails to speak to swaths of England – and Wales – and leaves these places open to political forces that want to sever their residual links to left politics for good. Circa 2006, it was the BNP. From around 2012 onwards, Ukip began to slowly push into Labour’s old heartlands. Now, the millionaire Ukip donor Arron Banks is said to be mulling over a new party that might capitalise on the support for Brexit in working-class Labour areas and deliver them a new political identity. The stakes, then, are unbelievably high: if the left cannot speak for the people it once represented as a matter of instinct, much more malign forces will.

If the left’s predicament comes down to a single fault, it is this. It is very good at demanding change, but pretty hopeless at understanding it. Supposedly radical elements too often regard deep technological shifts as the work of greedy capitalists and rightwing politicians, and demand that they are rolled back. Meanwhile, the self-styled moderates tend to advocate large-scale surrender, instead of recognising that technological and economic changes can create new openings for left ideas. A growing estrangement from the left’s traditional supporters makes these problems worse, and one side tends to cancel out the other. The result: as people experience dramatic change in their everyday lives, they form the impression that half of politics has precious little to say to them.

In a political reality as complex as ours, there are inevitable problems for the political right as well. It is a long time since the Conservative party has spoken the visceral, populist language that was the hallmark of Margaret Thatcher. As with Blair in 2005, the Tories were recently elected to power with the support of less than a quarter of the electorate. Similarly, in Germany, Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats once vied with the Social Democrats for the support of a majority of the population, but they are now down to around 30%. But modern challenges for the centre-right will always be less difficult than they are for the left. The former, after all, seeks to safeguard and advance modern capitalism rather than substantially change it. Even in the absence of a broad social base, the right is sustained by big business and the conservative press, which give it huge political advantages.

The left has responded to its crisis by looking endlessly inward – but occasionally, there are flashes of hope. There is a rising recognition, among both former followers of Blair and alumni of the traditional left, that Labour’s old majoritarian dreams are probably finished – and that it should finally embrace proportional representation and build new alliances and coalitions. This change would probably trigger a split between the party’s estranged left and right, and thereby bring Britain into line with the rest of Europe, where the left’s crisis is highlighted by a tussle between traditional social democrats and new radicals.

In Britain and plenty of other places, there is growing interest in the idea of a universal basic income, built on an understanding of accelerating economic changes, and their far-reaching consequences for the left’s almost religious attachment to the glories of paid employment. It is early days for such a leap. But proposing that the state should meet some or all of people’s basic living costs would be an implicit acknowledgement that work alone cannot possibly deliver the collective security that the left has always seen as its basic mission, and that space has to be created for the other elements of people’s lives.

Whether the left can come to terms with the new politics of national identity and belonging and thereby rein in its nastier aspects is a much more difficult question – but if it doesn’t, its activists may very well gaze at their parties’ old “core” supporters across an impossible divide.

Perhaps the most generous verdict is that here and across the world, the left – radicals and liberals alike – is stuck in an interregnum. You could compare it to the predicament of the 1980s, but it is even more reminiscent of the 1930s, when the aftershocks of an economic crash saw the left pushed aside by the politics of hatred and division.

In 1931, the great Labour thinker RH Tawney wrote a short text titled The Choice Before the Labour Party, casting a cold eye over its predicament in terms that ring as true now as they must have done then. Labour, he wrote, “does not achieve what it could, because it does not know what it wants. It frets out of office and fumbles in it, because it lacks the assurance either to wait or to strike. Being without clear convictions as to its own meaning and purpose, it is deprived of the dynamic which only convictions supply. If it neither acts with decision nor inspires others so to act, the principal reason is that it is itself undecided.”

No party can exist forever. Political traditions can decline, and then take on new forms; some simply become extinct. All that can be said with certainty is that if the left is to finally leave the 20th century, the process will have to start with the ideas and convictions that answer the challenges of a modernity it is only just starting to wake up to, let alone understand.

Friday, 1 April 2016

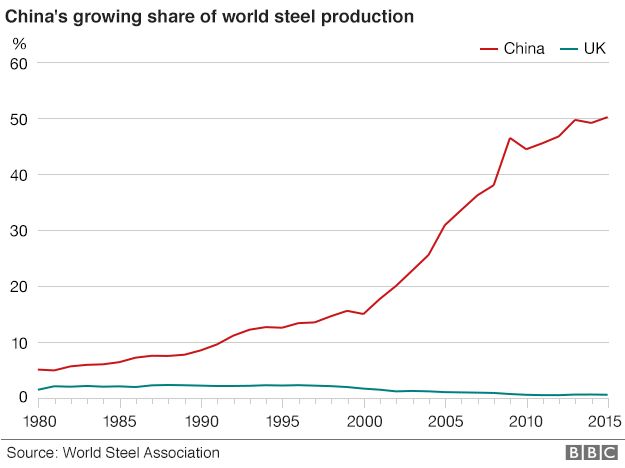

Steel v banks: Why they're different when it comes to a government bail-out

The economy can survive without British steel

Does it make financial sense?