Will Hutton in The Guardian

The elimination of Britain’s steel industry in a matter of weeks – the reality of Tata’s statement that it wants to close its UK operations – is, by any standards, shocking. There will be efforts to save something from the ruins, but the financial and trading truths are brutal.

This has not happened, however, in a day, or even over the past few years. Rather the plight of British steel making is the culmination of 40 years of refusal to organise economic, financial and industrial policy to support the generation of value. This is done in the laissez-faire belief – contested even in economic theory – that any such attempt is self-defeating. Business secretary Sajid Javid personifies this view. In fact, he is surely the most ideologically driven and least practical politician to hold this key post since the war.

The most generous interpretation is that this is creative destruction at work. Steel was an integral element of an industrial economy now giving way to a new knowledge-based capitalism where know-how is more important than brawn. It is tragic for those whose livelihoods and skills are now redundant, but it was no less tragic for ostlers, sailmakers and coal miners in their day.

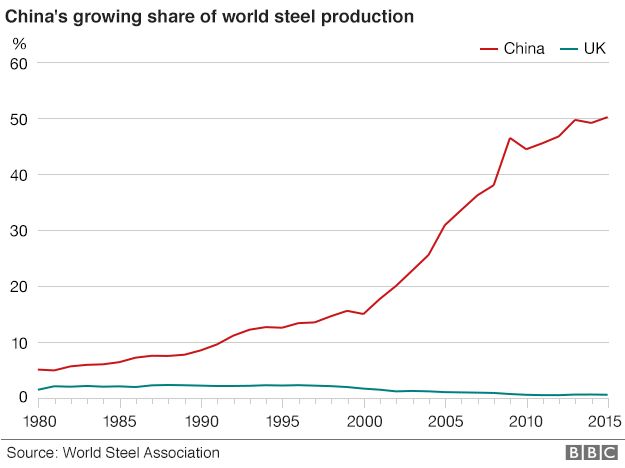

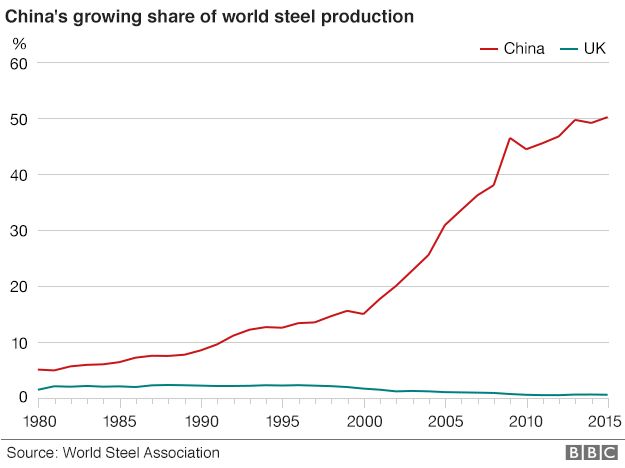

The trouble is that Britain is very good at destruction, much less good at the creative part. Nor is it clear that steel’s days are over: its usage in a range of key functions – from transport to construction – remains fundamental and is growing. Rather, the economic behemoth China has monumentally over-invested in steel, for which there is too little domestic demand, and is now flooding world markets.

Britain, with a systemically overvalued exchange rate, porous market, high energy costs and ideological refusal to join others in the EU to deter imports dumped below cost with higher tariffs, is uniquely exposed to the threat. Now up to 40,000 workers directly and indirectly connected to steel production are about to lose their livelihoods.

Beneath the specifics of the steel industry lie more deep-seated problems. The day after Tata’s announcement, the Office of National Statistics (ONS) disclosed that the country’s balance of payments deficit in the last quarter of 2015 climbed to a record 7% of GDP. Britain’s international accounts are more in the red than those of any other developed country. Imports of goods and services, which have steadily outstripped exports for decades, are now to be given an extra impetus by the closure of UK steel capacity. What’s more, the same weaknesses that plague the old also inhibit the growth of the new.

After the interventionism of the 1930s – or even the 1950s and 1960s – Britain could boast dozens of substantial companies representing industries as disparate as pharmaceuticals, chemicals, aerospace and electronics. Not so in 2016. Only two high-tech companies are represented in the FTSE 100 – ARM and Sage. Another 20 years of the laissez-faire framework Javid cherishes – he is a devotee of the wild philosopher of hyper-libertarianism Ayn Rand – and the economy will be eviscerated, with a current account deficit so large it cannot be conventionally financed. The consequences – on living standards, employment, inflation, interest rates and house prices – will be severe.

Start with the pound. Since it was forced out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992, the consensus has been that the state should make no effort to manage the exchange rate. The result is that for all but four or five of the past 24 years, the pound has been well above any calculation of its real value, buoyed up by money flowing into the UK to buy our companies and our property, notwithstanding our ever higher trade deficit.

This is an auction of national assets unmatched by any other industrialised country. But it also makes it harder for our producers to compete internationally. To manage the exchange rate, to shadow the euro or dollar, or even to consider joining the euro to lock in a competitive rate, are rejected with irrational hysteria. Result – a current account deficit of 7% of GDP.

Britain is rightly committed to free trade, but again to the point of irrationality. China’s Leninist corporatism cannot be understood as a market economy. The world’s steel producers should not be rendered uneconomic because China’s Communist party has overinvested in steel production to create jobs vital to its collapsing political legitimacy, and so dumps steel in world markets at below cost. It is an open and shut case of dumping, with protections provided by the rules of the WTO.

But the UK government, positioning itself as China’s biggest friend in the west in order to win investment in the UK nuclear industry, blocked the EU’s attempts to invoke the WTO rules. Thus we destroy our steel industry in exchange for Chinese state ownership of the next generation of nuclear power stations.

So the list continues. The combination of a privatised electricity industry – insisting on sky-high returns for strategic investment – with demanding targets for the reduction of carbon dioxide emissions has meant incredible rises in the price of electricity, especially for industrial users such as steel. Relief is too little and too late. More broadly the same effects impact across all of what remains of our manufacturing sector – so it becomes a less solid market for steel, adding one more twist to the downward vicious circle.

Britain needs a genuine march of the makers, in George Osborne’s phrase. But that would need a completely different policy paradigm, overturning the failed attempts of the past 40 years. There was a nascent attempt, launched by Peter Mandelson in 2009, and followed through in the coalition government by business secretary Vince Cable and science minister David Willetts, to create an intelligent industrial strategy.

Eight great technologies were identified in which Britain had strengths; convening councils were created to remove obstacles to their growth; the agency Innovate UK geared up to support frontier innovation; and a network of Catapults created to stimulate knowledge transfer, business start-ups and scale-ups. Foreign governments, impressed by what was happening, commissioned reports on the innovative UK.

Then came Javid, keen to deliver the swingeing cuts in his budget demanded by Osborne in his quest for the 36% state. After hobbling the admired innovation infrastructure with its role for a smart state, his first piece of legislation is the trade union bill.

Javid tilts at Thatcherite windmills – and shows little understanding of today’s industrial revolution. Nor does he seem to grasp how government can co-create opportunities with entrepreneurs – as well as ensuring that the big picture is as attractive as possible.

Something face-saving will be put together to soften the steel crisis, but there are bigger lessons to be learned. Be sure they will be ignored. The enfeebled Labour party is unable to press the points home and the Tory party remains transfixed by anti-state, laissez-faire nihilism. I mix rage with sadness for the next generation, and the inheritance it has been left.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label steel. Show all posts

Showing posts with label steel. Show all posts

Monday, 4 April 2016

Britain's free market economy isn't working

Larry Elliott in The Guardian

Last week should have been a good one for George Osborne. The first day of April marked the day when the ”national living wage” came into force. The idea was championed by the chancellor in his 2015 summer budget when he said it was time to “give Britain a pay rise”.

Unfortunately for the chancellor, the 50p an hour increase in the pay floor for workers over 25 was completely overshadowed by the existential threat to the steel industry posed by Tata’s decision to sell its UK plants.

Instead of being acclaimed by a grateful nation, Osborne found his handling of the economy under fire. The fact that official figures showed that Britain has the highest current account deficit since modern records began in 1948 did not help.

At one level, all seems well with the economy. Growth was revised up for the fourth quarter of 2015 to 0.6% and is running at an annual rate of just over 2% – close to its long-term average and higher than in Germany, France or Italy.

Two of three key sectors of the economy are struggling, though. Industrial production and construction have yet to recover the ground lost in the recession of 2008-09, leaving the economy dependent on services, which accounts for three-quarters of national output.

Digging beneath the surface glitter shows just how unbalanced and unsustainable the economy has become.

Growth is far too biased towards consumer spending. Borrowing is going up and imports are being sucked in. An enormous current account deficit and a collapse in the household saving ratio are usually consistent with the economy in the last stages of a wild boom rather than one trundling along at 2%.

A little extra digging provides the explanation, with some alarming structural flaws quickly emerging.

Here are two pieces of evidence. The first, relevant to the debate about the future of the steel industry, comes from an investigation by the left of centre thinktank,the IPPR, into the state of Britain’s foundation industries.

Foundation industries supply the basic goods – such as metal and chemicals – used by other industries. They have been having a tough time of it across the developed world, but the decline has been especially pronounced in the UK. Since 2000, the share of GDP accounted for by foundation industries has fallen by 21% across the rich nations that belong to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development but by 43% in Britain. At the end of the 1990s, imports accounted for 40% of UK demand for basic metals; import penetration is now at 90%. Clearly, this trend will become even more marked if the Tata steel plants close.

The second piece of evidence comes from a joint piece of research from the innovation foundation Nesta and the National Institute for Economic and Social Research being published on Monday. This found that productivity weaknesses are common across the sectors of the UK economy, but particularly marked among newly formed companies. Fledgling firms tend to be less efficient on average, but the report said that in the years since the recession performance had been unusually poor among startups.

Since the economy emerged from recession, the growth of highly productive companies has been curbed and there has also been a slowdown in the number of under-performing businesses contracting in size. This helps explain why Britain has an 18% productivity gap with the other members of the G7 group of industrial nations.

According to the economic orthodoxy that has prevailed for the past four decades, none of this should be happening. The theory was that a good, solid dose of market forces would clear out the dead wood from the manufacturing sector; financial deregulation would ensure that funding was provided to young, thrusting startup firms; and free trade would ensure that British industry remained on its toes. Industrial policy would no longer be about “picking winners” but involve an open door to inward investment and low corporate taxes.

This approach has proved a complete dud. Successive UK governments have allowed good companies to go to the wall for the sake of their free market principles. They have squandered the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity provided by North Sea oil to modernise and re-equip the manufacturing sector. They have sat back and watched as the economy has stumbled from one housing-driven boom-bust to another. They have now arrived at the stage where house price inflation is running at 10% a year; the current account deficit in the latest quarter was 7% a year; and manufacturing is in recession.

The UK has been here before, although this time the numbers are scarier. Traditionally, what happens next is a sharp fall in the value of the pound, which helps rebalance the economy by making exports cheaper and imports dearer.Consumer spending takes a hit because goods cost more in the shops while manufacturers get a boost because their products are more competitive on world markets.

Such a depreciation would almost certainly be triggered by a decision to leave the EU in the referendum on 23 June. The assumption is that this would be a bad thing; in truth, a cheaper currency would be one of the benefits of Brexit.

But only in the right circumstances. There is more to rebalancing the economy and solving the UK’s deep-seated problems than simply devaluing the pound. If it was as easy as that, Britain would be a world beater by now. Getting the right level for the pound is a necessary but not sufficient factor in putting the economy right.

There is no shortage of ideas. Help for steel would be provided if procurement rules were tightened up so that contractors had to show they were sourcing sustainably, with the test being the impact on the environment and on local communities. The IPPR has a range of ideas for boosting foundation industries, including building stronger supply chains with advanced manufacturing and using the regional growth fund to provide more patient finance.

Nesta said its research shows the need for better targeted support for new companies rather than blanket measures such as cuts in business rates.

A new paper for the Fabian Society by the former Labour MP and leadership contender Bryan Gould believes there should be a twin-tracked approach: a 30% depreciation of the currency accompanied by a focus on credit creation for investment. This, he argues, could happen either through the existing banking system under the direction of the Bank of England or, if necessary, through a national investment bank. Gould says this is not about “picking winners” but about setting the parameters for possible good investment opportunities.

What links all these ideas is the belief that Britain needs a proper long-term industrial strategy. The prerequisite for that is an admission that the current model – low investment and competing on cost rather than quality – has failed, is failing and will continue to fail.

Last week should have been a good one for George Osborne. The first day of April marked the day when the ”national living wage” came into force. The idea was championed by the chancellor in his 2015 summer budget when he said it was time to “give Britain a pay rise”.

Unfortunately for the chancellor, the 50p an hour increase in the pay floor for workers over 25 was completely overshadowed by the existential threat to the steel industry posed by Tata’s decision to sell its UK plants.

Instead of being acclaimed by a grateful nation, Osborne found his handling of the economy under fire. The fact that official figures showed that Britain has the highest current account deficit since modern records began in 1948 did not help.

At one level, all seems well with the economy. Growth was revised up for the fourth quarter of 2015 to 0.6% and is running at an annual rate of just over 2% – close to its long-term average and higher than in Germany, France or Italy.

Two of three key sectors of the economy are struggling, though. Industrial production and construction have yet to recover the ground lost in the recession of 2008-09, leaving the economy dependent on services, which accounts for three-quarters of national output.

Digging beneath the surface glitter shows just how unbalanced and unsustainable the economy has become.

Growth is far too biased towards consumer spending. Borrowing is going up and imports are being sucked in. An enormous current account deficit and a collapse in the household saving ratio are usually consistent with the economy in the last stages of a wild boom rather than one trundling along at 2%.

A little extra digging provides the explanation, with some alarming structural flaws quickly emerging.

Here are two pieces of evidence. The first, relevant to the debate about the future of the steel industry, comes from an investigation by the left of centre thinktank,the IPPR, into the state of Britain’s foundation industries.

Foundation industries supply the basic goods – such as metal and chemicals – used by other industries. They have been having a tough time of it across the developed world, but the decline has been especially pronounced in the UK. Since 2000, the share of GDP accounted for by foundation industries has fallen by 21% across the rich nations that belong to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development but by 43% in Britain. At the end of the 1990s, imports accounted for 40% of UK demand for basic metals; import penetration is now at 90%. Clearly, this trend will become even more marked if the Tata steel plants close.

The second piece of evidence comes from a joint piece of research from the innovation foundation Nesta and the National Institute for Economic and Social Research being published on Monday. This found that productivity weaknesses are common across the sectors of the UK economy, but particularly marked among newly formed companies. Fledgling firms tend to be less efficient on average, but the report said that in the years since the recession performance had been unusually poor among startups.

Since the economy emerged from recession, the growth of highly productive companies has been curbed and there has also been a slowdown in the number of under-performing businesses contracting in size. This helps explain why Britain has an 18% productivity gap with the other members of the G7 group of industrial nations.

According to the economic orthodoxy that has prevailed for the past four decades, none of this should be happening. The theory was that a good, solid dose of market forces would clear out the dead wood from the manufacturing sector; financial deregulation would ensure that funding was provided to young, thrusting startup firms; and free trade would ensure that British industry remained on its toes. Industrial policy would no longer be about “picking winners” but involve an open door to inward investment and low corporate taxes.

This approach has proved a complete dud. Successive UK governments have allowed good companies to go to the wall for the sake of their free market principles. They have squandered the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity provided by North Sea oil to modernise and re-equip the manufacturing sector. They have sat back and watched as the economy has stumbled from one housing-driven boom-bust to another. They have now arrived at the stage where house price inflation is running at 10% a year; the current account deficit in the latest quarter was 7% a year; and manufacturing is in recession.

The UK has been here before, although this time the numbers are scarier. Traditionally, what happens next is a sharp fall in the value of the pound, which helps rebalance the economy by making exports cheaper and imports dearer.Consumer spending takes a hit because goods cost more in the shops while manufacturers get a boost because their products are more competitive on world markets.

Such a depreciation would almost certainly be triggered by a decision to leave the EU in the referendum on 23 June. The assumption is that this would be a bad thing; in truth, a cheaper currency would be one of the benefits of Brexit.

But only in the right circumstances. There is more to rebalancing the economy and solving the UK’s deep-seated problems than simply devaluing the pound. If it was as easy as that, Britain would be a world beater by now. Getting the right level for the pound is a necessary but not sufficient factor in putting the economy right.

There is no shortage of ideas. Help for steel would be provided if procurement rules were tightened up so that contractors had to show they were sourcing sustainably, with the test being the impact on the environment and on local communities. The IPPR has a range of ideas for boosting foundation industries, including building stronger supply chains with advanced manufacturing and using the regional growth fund to provide more patient finance.

Nesta said its research shows the need for better targeted support for new companies rather than blanket measures such as cuts in business rates.

A new paper for the Fabian Society by the former Labour MP and leadership contender Bryan Gould believes there should be a twin-tracked approach: a 30% depreciation of the currency accompanied by a focus on credit creation for investment. This, he argues, could happen either through the existing banking system under the direction of the Bank of England or, if necessary, through a national investment bank. Gould says this is not about “picking winners” but about setting the parameters for possible good investment opportunities.

What links all these ideas is the belief that Britain needs a proper long-term industrial strategy. The prerequisite for that is an admission that the current model – low investment and competing on cost rather than quality – has failed, is failing and will continue to fail.

Friday, 1 April 2016

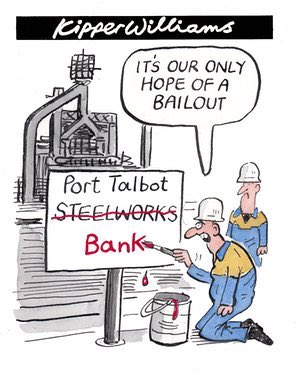

"You Don't Deserve a Bailout - You are NEITHER a Banker NOR Chinese"

If librarians and steelworkers wanted state bail-outs, they should have done something

useful - like bankers

In any case the bankers deserved to be bailed out, as they couldn’t possibly anticipate that if they kept taking money it might eventually run out, whereas steelworkers have caused their own downfall by not being Chinese.

Mark Steel in The Independent

The main thing to realise with the current steel industry crisis is that the government has been clear and decisive. They’ve stated firmly, “We’re not ruling out anything at all, though we are ruling out nationalising anything as that doesn’t count as anything, but we will do anything we possibly can that won’t make a difference such as drawing a pretty picture of a caterpillar, and we’re doing all we can because as we keep saying there’s nothing we can do, but we do feel desperately sorry for anyone who loses their job which is why any steelworkers who become redundant will immediately be called in to the job centre for an interview and told they won’t get any benefits if their answer to ‘Why have you let yourself be put of work?’ is ‘There was nothing I could do’.”

---Also read

------

Some people have pointed out that other industries were bailed out by governments in the past - but this has only been if they’ve produced essential goods, such as hedge funds and executive bonuses, not frivolities like the stuff that makes ships and teaspoons.

In any case the bankers deserved to be bailed out, as they couldn’t possibly anticipate that if they kept taking money it might eventually run out, whereas steelworkers have caused their own downfall by not being Chinese.

Luckily this sound economics is understood across the country, including by the sensible wing of the Labour Party such as those in charge of Lambeth Council, who are closing half the borough’s libraries and turning them into gyms.

This is the sort of can-do attitude people want from Labour. Hopefully it will spark off other schemes, such as turning social services departments into sushi bars, or converting disabled people’s wheelchairs into drones so they can be rented out to the RAF.

There’s no point in complaining about this; it’s the way the free market works. And if the Chinese are flooding South London with cheap Agatha Christies, we just have to accept it, and ask the elderly people who rely on going to libraries as their only point of contact with the community to spend all morning performing 200 reps of 40 kilograms per calf on a multi-gym body-solid squat machine instead.

One of these libraries, the Tate, has been assessed as receiving an average of 600 visits per day. This may seem successful, but where the library has let itself down is forgetting to charge any of them money for borrowing books and bringing kids into reading classes.

Maybe the library service should learn from gyms, and only let them in if they pay £40 a month on a minimum two-year contract. They could even offer them special courses in which an instructor screams, “Right, everyone, let’s all read this week’s Economist - you CAN do it - let’s drive ourselves to the limit - GO – ‘the Yen faces unexpected slow down’ - come on Eileen pick it up, PUSH everyone!”

The council insists they will preserve the essence of the libraries, because each of the gyms will include a “lounge with a limited supply of books”. Obviously they won’t have all those unnecessary books you see in old-fashioned libraries, but surely no one’s so fussy they insist on any specific book, as most books are pretty much the same.

The council also agreed that “under-18s may not be allowed in these lounges”, which will surely improve the service as rooms with books aren’t a suitable environment for the young.

Surprisingly, the local population appears shamefully ignorant about economics - so there have been daily protests against the closures, in which thousands have taken part. It seems these people don’t understand that it may have been all right to build and maintain free libraries back in the 1930s, but you can’t expect us to keep funding the luxuries we could afford back then.

So the council demanded a banner was taken down at one library, which was changed each day to tell people how many days were left until it was closed. Maybe the council hoped that if people weren’t reminded of the closure, they just wouldn’t notice. Then eventually they’d all tell stories of success and improvement to each other, such as: “I asked for a reference book on growing cucumbers and was sent into the corner. After three weeks I didn’t feel I was making any progress with my gardening, but then someone told me I’d spent the whole time benching 140 kilograms and now I’m the all-Hertfordshire Over-60s Bodybuilding champion.”

Nevertheless, the protests continue. But the libraries have probably been lending the wrong assets if they want state intervention. Instead of irresponsibly lending books to people who live round the corner so they can read and study and educate and entertain themselves and their kids, they should have lent billions of dollars to anyone who asked for it, without even suggesting a 40p fine if they kept it a week too long.

Then, once they’d succeeded in ruining the world economy, they’d have had a very reasonable case for being bailed out - unlike these people who want to fund steelworks and libraries because they don’t understand the world economy.

------- The China Tariff matter

The Guardian on 1/04/2014

China has risked raising tensions over its role in the UK steel crisis by imposing a 46% import duty on a type of high-tech steel made by Tata in Wales.

The Chinese government said it had slapped the tariff on “grain-oriented electrical steel” imported from the European Union, South Korea and Japan. It justified the move by saying imports from abroad were causing substantial damage to its domestic steel industry.

Tata Steel, whose subsidiary Cogent Power makes the hi-tech steel targeted by the levy in Newport, south Wales, was unable to say on Friday whether any Cogent products are exported to China.

News of the tariff emerged as David Cameron confronted the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, on the sidelines of a summit dinner in Washington on Thursday night, urging him to use Beijing’s presidency of the G20 group of leading countries to tackle the problem.

Asked if Cameron raised concerns about British job losses from Chinese steel dumping, a senior government source said: “He highlighted his concerns, yes.” The source added: “He made clear the concerns that we have on the impact this is having on the UK and other countries.”

British politicians have been accused of pandering to China by blocking new tariffs on Chinese imports to the EU, a measure designed to prop up Europe’s struggling steel industry.

The tariff move by the People’s Republic is likely to anger steelworkers and unions, who blame China for much of the industry’s recent troubles. Steel firms say one of the key reasons for the UK industry’s woes is that state-subsidised firms in China are “dumping” their product on the European market, due to flagging demand at home.

The UK business secretary, Sajid Javid, who visited Tata Steel’s struggling Port Talbot plant on Friday, has been accused of blocking measures to crack down on Chinese imports. Javid voted against EU plans to lift the “lesser duty” rule, which would have allowed for higher duties to be levied on Chinese steel imports. The UK has also lobbied for China to be granted “market economy status”, which would make it even harder to crack down on steel dumping.

“The fact is that the UK has been blocking this,” European Steel Association (Eurofer) spokesperson Charles de Lusignan told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme. “They are not the only member state but they are certainly the ring leader in blocking the lifting of the lesser duty rule. The ability to lift this was part of a proposal that the European commission launched in 2013, and the fact that the UK continues to block it means that when the government says it’s doing everything it can to save the steel industry in the UK and also in Europe, it’s not. It’s not true.”

The main thing to realise with the current steel industry crisis is that the government has been clear and decisive. They’ve stated firmly, “We’re not ruling out anything at all, though we are ruling out nationalising anything as that doesn’t count as anything, but we will do anything we possibly can that won’t make a difference such as drawing a pretty picture of a caterpillar, and we’re doing all we can because as we keep saying there’s nothing we can do, but we do feel desperately sorry for anyone who loses their job which is why any steelworkers who become redundant will immediately be called in to the job centre for an interview and told they won’t get any benefits if their answer to ‘Why have you let yourself be put of work?’ is ‘There was nothing I could do’.”

---Also read

Steel v banks: Why they're different when it comes to a government bail-out

------

Some people have pointed out that other industries were bailed out by governments in the past - but this has only been if they’ve produced essential goods, such as hedge funds and executive bonuses, not frivolities like the stuff that makes ships and teaspoons.

In any case the bankers deserved to be bailed out, as they couldn’t possibly anticipate that if they kept taking money it might eventually run out, whereas steelworkers have caused their own downfall by not being Chinese.

Luckily this sound economics is understood across the country, including by the sensible wing of the Labour Party such as those in charge of Lambeth Council, who are closing half the borough’s libraries and turning them into gyms.

This is the sort of can-do attitude people want from Labour. Hopefully it will spark off other schemes, such as turning social services departments into sushi bars, or converting disabled people’s wheelchairs into drones so they can be rented out to the RAF.

There’s no point in complaining about this; it’s the way the free market works. And if the Chinese are flooding South London with cheap Agatha Christies, we just have to accept it, and ask the elderly people who rely on going to libraries as their only point of contact with the community to spend all morning performing 200 reps of 40 kilograms per calf on a multi-gym body-solid squat machine instead.

One of these libraries, the Tate, has been assessed as receiving an average of 600 visits per day. This may seem successful, but where the library has let itself down is forgetting to charge any of them money for borrowing books and bringing kids into reading classes.

Maybe the library service should learn from gyms, and only let them in if they pay £40 a month on a minimum two-year contract. They could even offer them special courses in which an instructor screams, “Right, everyone, let’s all read this week’s Economist - you CAN do it - let’s drive ourselves to the limit - GO – ‘the Yen faces unexpected slow down’ - come on Eileen pick it up, PUSH everyone!”

The council insists they will preserve the essence of the libraries, because each of the gyms will include a “lounge with a limited supply of books”. Obviously they won’t have all those unnecessary books you see in old-fashioned libraries, but surely no one’s so fussy they insist on any specific book, as most books are pretty much the same.

The council also agreed that “under-18s may not be allowed in these lounges”, which will surely improve the service as rooms with books aren’t a suitable environment for the young.

Surprisingly, the local population appears shamefully ignorant about economics - so there have been daily protests against the closures, in which thousands have taken part. It seems these people don’t understand that it may have been all right to build and maintain free libraries back in the 1930s, but you can’t expect us to keep funding the luxuries we could afford back then.

So the council demanded a banner was taken down at one library, which was changed each day to tell people how many days were left until it was closed. Maybe the council hoped that if people weren’t reminded of the closure, they just wouldn’t notice. Then eventually they’d all tell stories of success and improvement to each other, such as: “I asked for a reference book on growing cucumbers and was sent into the corner. After three weeks I didn’t feel I was making any progress with my gardening, but then someone told me I’d spent the whole time benching 140 kilograms and now I’m the all-Hertfordshire Over-60s Bodybuilding champion.”

Nevertheless, the protests continue. But the libraries have probably been lending the wrong assets if they want state intervention. Instead of irresponsibly lending books to people who live round the corner so they can read and study and educate and entertain themselves and their kids, they should have lent billions of dollars to anyone who asked for it, without even suggesting a 40p fine if they kept it a week too long.

Then, once they’d succeeded in ruining the world economy, they’d have had a very reasonable case for being bailed out - unlike these people who want to fund steelworks and libraries because they don’t understand the world economy.

@@@@@@

------- The China Tariff matter

Steel tariff row explained

Here’s a Q&A on the steel tariffs row, from Kate Ferguson of the Press Association.

Q: What is a tariff?

A tariff is a form of tax imposed on goods or services imported from abroad. It can restrict trade by making products more expensive, and can be used as a form of protectionism - to protect and encourage domestic industry.Many in the UK steel industry have demanded higher tariffs be imposed on imported steel amid concerns Chinese steel dumping has sent prices plummeting.

Q: What is steel dumping and why are the Chinese accused of it?

Steel production in China has soared over the past decade and it now produces around half of the world’s annual output of 1.6 billion tonnes. But its domestic market has been slowing, leading steel producers to seek to export more.China has been accused of “dumping” its steel on European markets - which means selling it not just cheaply, but at a loss. In 2014, Chinese steel imports to the UK cost €583 a tonne compared to €897 a tonne for steel produced elsewhere in the EU, according to reports quoting the EU’s statistics agency, Eurostat.

Q: Why has the British Government been criticised for not doing enough to protect the UK steel industry?

Sharply falling prices and a flood of cheap, foreign steel has sparked major concern for the future of the British steel industry, and the many jobs that depend on it.British ministers blocked proposals in the EU to get rid of the “lesser duty rule” which caps tariffs at 9% - in the US some products face a tariff of up to 236%. The British Government has said the 9% tariff is too low, but warned against lurching towards protectionism.The debate comes as Britain has been courting China hard in a bid to foster closer trade links. Chancellor George Osborne said the two nations should “stick together and create a golden decade” while on a visit to China last September.The following month, Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Britain and was treated to a State banquet at Buckingham Palace, where he sat between the Queen and the Duchess of Cambridge.Set in this context, the Government has been accused of betraying British steelworkers to curry favour with the Chinese.

The Guardian on 1/04/2014

China has risked raising tensions over its role in the UK steel crisis by imposing a 46% import duty on a type of high-tech steel made by Tata in Wales.

The Chinese government said it had slapped the tariff on “grain-oriented electrical steel” imported from the European Union, South Korea and Japan. It justified the move by saying imports from abroad were causing substantial damage to its domestic steel industry.

Tata Steel, whose subsidiary Cogent Power makes the hi-tech steel targeted by the levy in Newport, south Wales, was unable to say on Friday whether any Cogent products are exported to China.

News of the tariff emerged as David Cameron confronted the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, on the sidelines of a summit dinner in Washington on Thursday night, urging him to use Beijing’s presidency of the G20 group of leading countries to tackle the problem.

Asked if Cameron raised concerns about British job losses from Chinese steel dumping, a senior government source said: “He highlighted his concerns, yes.” The source added: “He made clear the concerns that we have on the impact this is having on the UK and other countries.”

British politicians have been accused of pandering to China by blocking new tariffs on Chinese imports to the EU, a measure designed to prop up Europe’s struggling steel industry.

The tariff move by the People’s Republic is likely to anger steelworkers and unions, who blame China for much of the industry’s recent troubles. Steel firms say one of the key reasons for the UK industry’s woes is that state-subsidised firms in China are “dumping” their product on the European market, due to flagging demand at home.

The UK business secretary, Sajid Javid, who visited Tata Steel’s struggling Port Talbot plant on Friday, has been accused of blocking measures to crack down on Chinese imports. Javid voted against EU plans to lift the “lesser duty” rule, which would have allowed for higher duties to be levied on Chinese steel imports. The UK has also lobbied for China to be granted “market economy status”, which would make it even harder to crack down on steel dumping.

“The fact is that the UK has been blocking this,” European Steel Association (Eurofer) spokesperson Charles de Lusignan told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme. “They are not the only member state but they are certainly the ring leader in blocking the lifting of the lesser duty rule. The ability to lift this was part of a proposal that the European commission launched in 2013, and the fact that the UK continues to block it means that when the government says it’s doing everything it can to save the steel industry in the UK and also in Europe, it’s not. It’s not true.”

Steel v banks: Why they're different when it comes to a government bail-out

Jay Cockburn BBC Money

The British steel industry is in a perilous position right now.

Tata Steel is looking to pull out of the UK; they own most of Britain's steelworks.

It's led to mutterings of government intervention, after all they put up the cash to bail out the banks in 2008.

Why shouldn't they do the same for the steel industry?

The thing is, they're totally different situations.

Some of the banks were unable to balance their books with the Bank of England, and some ATMs ran out cash.

The government stepped in and first saved Northern Rock.

Image captionCustomers queue to take their cash out from Northern Rock

Then it was Bradford and Bingley, closely followed by taking stakes in RBS, Lloyds TSB, HBOS.

The reasons behind the global financial crisis were complex, countless films and documentaries have been made in an attempt to explain why it happened.

Everyone involved in the bailout assumed the banks would recover, and they did (even if it feels like it took forever).

The economy can survive without British steel

The UK is a global centre for banking. Without banks there is nobody to lend money to people to start businesses, or buy homes.

A lot depends on our banks, not just in the UK but around the world.

That's clearly not the same for steel.

One of the problems is the UK industry has been shrinking for a long time. Employment has fallen from around 50,000 in 1990 to under 20,000 today.

Image captionCanary Wharf in London is one of the world's major financial centres

Other countries, such as China, make steel, and they do it for cheaper than we do. The people in the steel industry and the towns like Port Talbot depend on the steel industry, but the rest of the economy will cope without it.

Globally we are a major player in the financial market but our steel output is actually fairly insignificant. We currently put out around 12 million tonnes a year; China's output is 822 million tonnes - although the British industry does tend to specialise in high quality, high value steel.

Does it make financial sense?

The government will be weighing up the financial cost of making thousands of people unemployed.

One think-tank, the Institute for Public Policy Research, estimates that as many as 40,000 jobs depend on the sector.

Image captionThe steel plant at Redcar which closed last year leading to 1700 job losses

During the financial crisis UK unemployment peaked at 2.7 million - a little over 8% of the total workforce. If we hadn't bailed out the banks it's likely that figure would have been even higher, costing the government huge amounts of money in benefits and lost tax revenue.

In the UK we have a workforce of around 31 million. 40,000 is just 0.12% of that workforce. When Port Talbot steelworks is thought to be losing around £1 million a day the government may find that number a little more palatable.

The government can't legally buy the plants

The Prime Minister himself, David Cameron has indicated that they're unwilling to buy the plants: "I don't believe nationalisation is the right answer".

Whether they are willing or not might be irrelevant though, because the UK is a member of the European Union.

By law EU member states cannot rescue failing companies in the steel sector.

These are rules that were agreed on by every member of the EU, including the UK.

Exceptions to those rules on bailing out companies exist, but governments have to prove their economy is in danger - that's why they allowed the banks to be rescued.

But the EU has decided that allowing failing steel companies to go bust is good for the union as a whole.

But...

Unlikely as it may be the EU does still have the final say so it's not entirely impossible for the government to step in.

The decisions on state aid are often highly political though, but ultimately the Commission can decide to approve it.

But if any of the 28 member states don't agree they can challenge the decision - and that can take lots more time.

Wednesday, 28 October 2015

Why don’t we save our steelworkers, when we’ve spent billions on bankers?

Aditya Chakrabortty in The Guardian

‘Britain is entering the early stages of yet another industrial catastrophe.’ Illustration by Andrzej Krauze

Every so often a society decides which of its citizens really matter. Which ones get the star treatment and the big cash handouts – and which get shoved to the bottom of the pile and penalised. These are the big, rough choices post-crash Britain is making right now.

A new hierarchy is being set in place by David Cameron in budget after austerity budget. Wealthy pensioners: winners. Young would-be homeowners: losers. Millionaires see their taxes cut to 45%, while the working poor pay a marginal tax rate of 80%. Big business gets to write its own tax code; benefit claimants face harsh sanctions.

When the contours of this new social order are easy to spot, they can cause public uproar – as with the cuts to tax credits. Elsewhere, they’re harder to pick out, though still central. It is into this category that the crisis in the British steel industry falls.

Every so often a society decides which of its citizens really matter. Which ones get the star treatment and the big cash handouts – and which get shoved to the bottom of the pile and penalised. These are the big, rough choices post-crash Britain is making right now.

A new hierarchy is being set in place by David Cameron in budget after austerity budget. Wealthy pensioners: winners. Young would-be homeowners: losers. Millionaires see their taxes cut to 45%, while the working poor pay a marginal tax rate of 80%. Big business gets to write its own tax code; benefit claimants face harsh sanctions.

When the contours of this new social order are easy to spot, they can cause public uproar – as with the cuts to tax credits. Elsewhere, they’re harder to pick out, though still central. It is into this category that the crisis in the British steel industry falls.

Tata Steel confirms 1,200 job losses as industry crisis deepens

It would be easy to tune out the past few weeks’ headlines about plant closures and job losses as just another story of business disaster. But what’s happening to our steelworkers, and what we do to protect them, goes to the heart of the debate about which people – and which places – count in Britain’s political economy.

If Westminster lets the UK’s steel industry die, it’s in effect declaring that certain regions and the people who live and work in them are surplus to requirements. That it really doesn’t matter if Britain makes things. That the phrase “skilled working-class jobs” is now little more than an oxymoron. That’s the criteria against which to judge MPs, as they continue to take evidence today on the crisis and then debate options.

What does this crisis look like? Imagine coming to work on a September morning – only to find that you and one in six other employees in your entire industry face redundancy before Christmas. That’s the prospect facing British steelworkers. Motherwell, Middlesbrough, Scunthorpe: some of the most kicked-about places in de-industrialised Britain now face more punishment.

Mothball the SSI plant in Redcar and it’s not just 2,200 workers that you send to the dole office and whose families you shove on the breadline. An entire local economy goes on life support: the suppliers of parts, the outside engineers who used to do the servicing, the port workers and hauliers, the cafes and shops. Within days of SSI’s closure, one of Teesside’s biggest employment agencies went into liquidation.

‘If Westminster lets the UK’s steel industry die, it’s effectively declaring that certain regions and the people who live and work in them are surplus to requirements.’ Photograph: Nigel Roddis/Reuters

Steel is a fundamental part of manufacturing, so that the closure of a handful of steelworks in Scotland and the north endangers businesses in Derby and Walsall. At the West Midlands Economic Forum, the chief economist Paul Forrest calculates that about 260,000 jobs in the Midlands rely on steel for everything from basic metals to car assembly and aerospace engineering. He believes that the closures at Tata, SSI and Caparo leave 52,000 local manufacturing workers at direct risk of losing their jobs within the next five years. That’s just after the past few weeks – the UK Steel director Gareth Stace thinks that more plants face closure “within months”.

Join up these predictions, and Britain is entering the early stages of yet another industrial catastrophe. It could finally sink a sector, steel, that actually helps reduce the country’s gaping trade deficit. With that will go another pocket of well-paid blue-collar jobs. Chuck in employer contributions to pensions and national insurance, and the total remuneration per SSI staffer is £40,000 a year. Just try getting such pay in a call centre or distribution warehouse, even as a manager.

Imagine what would happen if manufacturing were centred around the capital, and its executives had Downing Street on speed dial. Actually, you needn’t imagine – merely remember the meltdown of 2008. Then Gordon Brown was so desperate to save the City that the IMF estimates he propped it up with £1.2 trillion of public money. That’s the equivalent of nearly £20,000 from every man, woman and child in the country doled out to bankers in direct cash, loans and taxpayer guarantees.

That’s what the state can do when it decides a sector matters. In 2011 David Cameron stormed out of a Brussels summit rather than agree to more regulation on the City. When it comes to steel, his ministers shrug at the difficulties posed by the EU’s state-aid rules. Michael Heseltine even declares this a “good time” for Teesside’s workers to lose their jobs in Britain’s “exciting” labour market. Let them eat benefits!

True, the problems in the steel industry aren’t confined to these shores. They’re driven by a world economy coming off the boil and China dumping its excess steel output on the global market. Yet other European governments are being far more aggressive in confronting them. Italy’s prime minister, Matteo Renzi, bailed out a huge steelworks last December. Germany’s Angela Merkel ensures that steel producers are cushioned from higher energy prices.

Just how lame, by comparison, is Cameron? Here’s an example: the European commission runs a publicly funded globalisation adjustment fund that can grant over £100m a year for precisely the sort of situation British steelworkers now face. The Germans, the French, the Dutch: they’ve all drawn down many millions apiece. The British? European commission officials told me this week that they had never so much as seen an application from the UK. Here’s a giant pot of money – into which Whitehall can’t even be bothered to dip its fingers.

Once our steel capacity is gone, it’s gone – and with it goes a big chunk of what’s left of our manufacturing base. Whole swaths of the country that have only just got off their backs after Thatcher’s de-industrial revolution will be knocked to the floor all over again.

The choice is stark. Westminster can sit on its hands, pretend it can’t do anything about the supposedly free market in steel (in which the single biggest player is the Chinese Communist party), and let tens of thousands of families go to the wall. Or our political class acts as if its job is actually to protect people from market fluctuations – and keep the steel industry afloat by extended bridging loans and capital investment in return for public stakes.

A return to British Leyland? No: a far cheaper and smaller rescue than RBS and HBOS. Free-market fundamentalists will decry this as a wage subsidy to steelworkers. But the alternative is to wind up paying far more in benefits to thousands of unemployed workers and their families. Besides, the state already shells out billions in hidden wage subsidies, through the tax credits and housing benefit that taxpayers give to employees of poverty-pay firms such as Sports Direct and Amazon.

What’s being proposed here is open, transparent support to employees in normally high-paying and high-skilled jobs. To keep a vital industry from disappearing for good. And to show that it’s not just the City that matters.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)