Ruchir Sharma in The FT

As bank runs spread, it has become clear that anyone who questions a government rescue for those caught underfoot will be tarred as a latter-day liquidationist, like those who advised Herbert Hoover to let businesses fail after the crash of 1929.

Liquidationist is now challenging fascist as the most inaccurately thrown insult in politics. True, it’s no longer politically possible for governments not to stage rescues, but this is a snowballing problem of their own making. The past few decades of easy money created markets so large — nearing five times larger than the world economy — and so intertwined, that the failure of even a midsize bank risks global contagion.

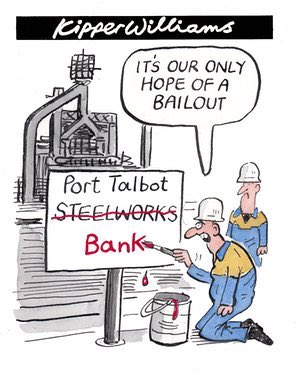

More than low interest rates, the easy money era was shaped by an increasingly automatic state reflex to rescue — to rescue the economy from disappointing growth even during recoveries, to rescue not only banks and other companies but also households, industries, financial markets and foreign governments in times of crisis.

The latest bank runs show that the easy money era is not over. Inflation is back so central banks are tightening, but the rescue reflex is still gaining strength. The stronger it grows, the less dynamic capitalism becomes. In stark contrast to the minimalist state of the pre-1929 era, America now leads a rescue culture that keeps growing to new maximalist extremes.

Today’s troubles have been compared to bank runs of the 19th century, but rescues were rare in those days. America’s founding hostility to concentrated power had left it with limited central government and no central bank. In the absence of a financial system, trust was kept at a personal, not an institutional level. Before the civil war, private banks issued their own currencies and when trust failed, depositors fled.

Had the US Federal Reserve existed at the time, it would not have helped much. The ethos of contemporary European central banks was to help solvent banks with solid collateral — in practice they were tougher, protecting their own reserves and “turning away their correspondents in need”, as a Fed history puts it.

A restrained government was a key feature of the industrial revolution, marked by painful downturns and robust recoveries, resulting in strong productivity and higher per capita income growth. Right into the 1960s and 1970s, resistance to state rescues still ran deep, whether the supplicant was a major bank, a major corporation or New York City.

Though the early 1980s is seen as a pivotal moment of broader government retreat, in fact this era was marked by the rise of rescue culture when Continental Illinois became the first US bank deemed too big to fail. In a move that was radical then, reflexive now, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation extended unlimited protection to Continental depositors — just as it has done for SVB depositors.

Recent bank runs have been compared to the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s. Triggered in part by regulation that made it impossible for S&Ls to compete in an environment of rising rates, the crisis was resolved by regulators who wound down more than 700 of these “thrifts” at a cost to taxpayers of about $130bn. The first preventive rescue came in the late 1990s, when the Fed organised support for a hedge fund deeply tied to foreign markets, in order to avoid the threat of a systemic financial crisis.

Those rescues pale next to 2008 and 2020, when the Fed and Treasury smashed records for trillions of dollars created or extended in loans and bailouts to thousands of companies across finance and other industries at home and abroad. In each crisis, rescues held down the corporate default rate to levels that were unexpectedly low, compared with past patterns. They are doing the same now even as rates rise and bank runs begin.

The hazards are not just moral or speculative, as many insist — they are practical and present. The rescues have led to a massive misallocation of capital and a surge in the number of zombie firms, which contribute mightily to weakening business dynamism and productivity. In the US, total factor productivity growth fell to just 0.5 per cent after 2008, down from about 2 per cent between 1870 and the early 1970s.

Instead of re-energising the economy, the maximalist rescue culture is bloating and thereby destabilising the global financial system. As fragility grows, each new rescue hardens the case for the next one.

No one who thinks about it for more than a minute can wax nostalgic for the painful if productive chaos of the pre-1929 era. But too few policymakers recognise that we are at an opposite extreme; constant rescues undermine capitalism. Government intervention eases the pain of crises but over time lowers productivity, economic growth and living standards.