Tim Harford in The Financial Times

In the middle of a crisis, it is not always easy to work out what has changed forever, and what will soon fade into history. Has the coronavirus pandemic ushered in the end of the office, the end of the city, the end of air travel, the end of retail and the end of theatre? Or has it merely ruined a lovely spring?

Stretch a rubber band, and you can expect it to snap back when released. Stretch a sheet of plastic wrapping and it will stay stretched. In economics, we borrow the term “hysteresis” to refer to systems that, like the plastic wrap, do not automatically return to the status quo.

The effects can be grim. A recession can leave scars that last, even once growth resumes. Good businesses disappear; people who lose jobs can then lose skills, contacts and confidence. But it is surprising how often, for better or worse, things snap back to normal, like the rubber band.

The murderous destruction of the World Trade Center in 2001, for example, had a lasting impact on airport security screening, but Manhattan is widely regarded to have bounced back quickly. There was a fear, at the time, that people would shun dense cities and tall buildings, but little evidence that they really did.

What, then, will the virus change permanently? Start with the most obvious impact: the people who have died will not be coming back. Most were elderly but not necessarily at death’s door, and some were young. More than one study has estimated that, on average, victims of Covid-19 could have expected to live for more than a decade.

But some of the economic damage will also be irreversible. The safest prediction is that activities which were already marginal will struggle to return.

After the devastating Kobe earthquake in Japan in 1995, economic recovery was impressive but partial. For a cluster of businesses making plastic shoes, already under pressure from Chinese competition, the earthquake turned a slow decline into an abrupt one.

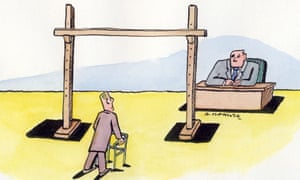

Ask, “If we were starting from scratch, would we do it like this again?” If the answer is No, do not expect a post-coronavirus rebound. Drab high streets are in trouble.

But there is not necessarily a correlation between the hardest blow and the most lingering bruise.

Consider live music: it is devastated right now — it is hard to conceive of a packed concert hall or dance floor any time soon.

Yet live music is much loved and hard to replace. When Covid-19 has been tamed — whether by a vaccine, better treatments or familiarity breeding indifference — the demand will be back. Musicians and music businesses will have suffered hardship, but many of the venues will be untouched. The live experience has survived decades of competition from vinyl to Spotify. It will return.

Air travel is another example. We’ve had phone calls for a very long time, and they have always been much easier than getting on an aeroplane. They can replace face-to-face meetings, but they can also spark demand for further meetings. Alas for the planet, much of the travel that felt indispensable before the pandemic will feel indispensable again.

And for all the costs and indignities of a modern aeroplane, tourism depends on travel. It is hard to imagine people submitting to a swab test in order to go to the cinema, but if that becomes part of the rigmarole of flying, many people will comply.

No, the lingering changes may be more subtle. Richard Baldwin, author of The Globotics Upheaval, argues that the world has just run a massive set of experiments in telecommuting. Some have been failures, but the landscape of possibilities has changed.

If people can successfully work from home in the suburbs, how long before companies decide they can work from low-wage economies in another timezone?

The crisis will also spur automation. Robots do not catch coronavirus and are unlikely to spread it; the pandemic will not conjure robot barbers from thin air, but it has pushed companies into automating where they can. Once automated, those jobs will not be coming back.

Some changes will be welcome — a shock can jolt us out of a rut. I hope that we will strive to retain the pleasures of quiet streets, clean air and communities looking out for each other.

But there will be scars that last, especially for the young. People who graduate during a recession are at a measurable disadvantage relative to those who are slightly older or younger. The harm is larger for those in disadvantaged groups, such as racial minorities, and it persists for many years.

And children can suffer long-term harm when they miss school. Those who lack computers, books, quiet space and parents with the time and confidence to help them study are most vulnerable. Good-quality schooling is supposed to last a lifetime; its absence may be felt for a lifetime, too.

This crisis will not last for decades, but some of its effects will.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label outsourcing. Show all posts

Showing posts with label outsourcing. Show all posts

Friday, 5 June 2020

Wednesday, 27 May 2020

Privatisation is at the heart of the UK's disastrous coronavirus response

George Monbiot in The Guardian

Amid the smog of lies and contradictions, there is one question we should never stop asking: why has the government of the United Kingdom so spectacularly failed to defend people’s lives? Why has “this fortress built by Nature for herself against infection”, as Shakespeare described our islands, succumbed to a greater extent than any other European nation to a foreseeable and containable pandemic?

Part of the answer is that the government knowingly and deliberately stood down crucial parts of its emergency response system. Another part is that, when it did at last seek to mobilise the system, crucial bits of the machine immediately fell off. There is a consistent reason for the multiple, systemic failures the pandemic has exposed: the intrusion of corporate power into public policy. Privatisation, commercialisation, outsourcing and offshoring have severely compromised the UK’s ability to respond to a crisis.

Take, for example, the lethal failures to provide protective clothing, masks and other equipment (PPE) to health workers. A report by the campaigning group We Own It seeks to explain why so many doctors, nurses and other hospital workers have died unnecessarily of Covid-19. It describes a system built around the needs not of health workers or patients, but of corporations and commercial contracts: a system that could scarcely be better designed for failure.

Four layers of commercial contractors, each rich with opportunities for profit-making, stand between doctors and nurses and the equipment they need. These layers are then fragmented into 11 tottering, uncoordinated supply chains, creating an almost perfect formula for chaos. Among the many weak links in these chains are consultancy companies like Deloitte, whose farcical attempts to procure emergency supplies of PPE have been fiercely criticised by both manufacturers and health workers.

At the end of the chains are manufacturing companies, some of which have mysteriously been granted monopolies on the supply of essential equipment. These private monopolies have either failed to meet their contracts, or provided defective gear to the entire NHS, like the 15m protective goggles and the planeload of useless surgical gowns that had to be recalled.

Instead of stockpiling supplies, as emergency preparedness demands, companies in these chains have been using just-in-time production systems, whose purpose is to cut their costs by minimising stocks. Their minimised systems could not be scaled up fast enough to meet the shortfall. Where there should be a smooth, coordinated, accountable programme, there’s opacity, byzantine complexity and total chaos. So much for the efficiencies of privatisation.

The pandemic has also exposed the privatised care system as catastrophically unfit and ill-prepared. In 1993, 95% of care at home was provided publicly by local authorities. Now, almost all of it – and almost all residential care – is provided by private companies. Even before the pandemic, the system was falling apart, as many care companies, unable to balance the needs of their patients with the demands of their shareholders, collapsed, often with disastrous consequences.

Now we discover just how dangerous their commercial imperatives have become, as the drive to make care profitable has created a fragmented, incoherent system, answerable sometimes to offshore owners, that fails to meet basic standards, and employs harassed workers on zero-hour contracts. If there is one thing we have learnt from this pandemic, it’s the need for a publicly owned, publicly run National Care Service – the care equivalent of the NHS.

It could all become much worse, due to another effect of corporate power. A report by the Corporate Europe Observatory shows how law firms are exploring the possibility of suing governments for the measures they have taken to stop the pandemic. Many trade treaties contain a provision called “investor state dispute settlement”. This enables corporations to sue governments in opaque offshore tribunals, for any policies that might affect their “future anticipated profits”.

So when governments, in response to coronavirus, have imposed travel restrictions, or requisitioned hotels, or instructed companies to produce medical equipment or limit the price of drugs, the companies could sue them for the loss of the money they might otherwise have made. When the UK government commandeers private hospitals or the Spanish government prevents evictions by landlords, and stops water and electricity companies from cutting off destitute customers, they could be open to international legal challenge. These measures, which override democracy, have already hampered attempts by many governments, particularly of poorer nations, to protect their people from disasters. They urgently need to be rescinded.

The effectiveness of our health system is also threatened by the trade treaty the UK government hopes to sign with the US. The Conservatives promised in their manifesto that “the NHS is not on the table” in the trade talks. But they have already broken their accompanying promise, “we will not compromise on our high environmental protection, animal welfare and food standards”. Earlier this month, they voted that measure out of the agriculture bill. US companies are aggressively demanding access to the NHS. The talks will be extremely complex and incomprehensible to almost everyone. There will be plenty of opportunities to give them what they want while fooling voters.

Boris Johnson’s central mission, overseen by Dominic Cummings, is to break down all barriers between government and the power of money. It is to allow private interests to intrude into the very heart of government, while marginalising the civil service. This helps to explain why Johnson is so reluctant to let Cummings go. The disasters of the past few weeks hint at the likely results.

Amid the smog of lies and contradictions, there is one question we should never stop asking: why has the government of the United Kingdom so spectacularly failed to defend people’s lives? Why has “this fortress built by Nature for herself against infection”, as Shakespeare described our islands, succumbed to a greater extent than any other European nation to a foreseeable and containable pandemic?

Part of the answer is that the government knowingly and deliberately stood down crucial parts of its emergency response system. Another part is that, when it did at last seek to mobilise the system, crucial bits of the machine immediately fell off. There is a consistent reason for the multiple, systemic failures the pandemic has exposed: the intrusion of corporate power into public policy. Privatisation, commercialisation, outsourcing and offshoring have severely compromised the UK’s ability to respond to a crisis.

Take, for example, the lethal failures to provide protective clothing, masks and other equipment (PPE) to health workers. A report by the campaigning group We Own It seeks to explain why so many doctors, nurses and other hospital workers have died unnecessarily of Covid-19. It describes a system built around the needs not of health workers or patients, but of corporations and commercial contracts: a system that could scarcely be better designed for failure.

Four layers of commercial contractors, each rich with opportunities for profit-making, stand between doctors and nurses and the equipment they need. These layers are then fragmented into 11 tottering, uncoordinated supply chains, creating an almost perfect formula for chaos. Among the many weak links in these chains are consultancy companies like Deloitte, whose farcical attempts to procure emergency supplies of PPE have been fiercely criticised by both manufacturers and health workers.

At the end of the chains are manufacturing companies, some of which have mysteriously been granted monopolies on the supply of essential equipment. These private monopolies have either failed to meet their contracts, or provided defective gear to the entire NHS, like the 15m protective goggles and the planeload of useless surgical gowns that had to be recalled.

Instead of stockpiling supplies, as emergency preparedness demands, companies in these chains have been using just-in-time production systems, whose purpose is to cut their costs by minimising stocks. Their minimised systems could not be scaled up fast enough to meet the shortfall. Where there should be a smooth, coordinated, accountable programme, there’s opacity, byzantine complexity and total chaos. So much for the efficiencies of privatisation.

The pandemic has also exposed the privatised care system as catastrophically unfit and ill-prepared. In 1993, 95% of care at home was provided publicly by local authorities. Now, almost all of it – and almost all residential care – is provided by private companies. Even before the pandemic, the system was falling apart, as many care companies, unable to balance the needs of their patients with the demands of their shareholders, collapsed, often with disastrous consequences.

Now we discover just how dangerous their commercial imperatives have become, as the drive to make care profitable has created a fragmented, incoherent system, answerable sometimes to offshore owners, that fails to meet basic standards, and employs harassed workers on zero-hour contracts. If there is one thing we have learnt from this pandemic, it’s the need for a publicly owned, publicly run National Care Service – the care equivalent of the NHS.

It could all become much worse, due to another effect of corporate power. A report by the Corporate Europe Observatory shows how law firms are exploring the possibility of suing governments for the measures they have taken to stop the pandemic. Many trade treaties contain a provision called “investor state dispute settlement”. This enables corporations to sue governments in opaque offshore tribunals, for any policies that might affect their “future anticipated profits”.

So when governments, in response to coronavirus, have imposed travel restrictions, or requisitioned hotels, or instructed companies to produce medical equipment or limit the price of drugs, the companies could sue them for the loss of the money they might otherwise have made. When the UK government commandeers private hospitals or the Spanish government prevents evictions by landlords, and stops water and electricity companies from cutting off destitute customers, they could be open to international legal challenge. These measures, which override democracy, have already hampered attempts by many governments, particularly of poorer nations, to protect their people from disasters. They urgently need to be rescinded.

The effectiveness of our health system is also threatened by the trade treaty the UK government hopes to sign with the US. The Conservatives promised in their manifesto that “the NHS is not on the table” in the trade talks. But they have already broken their accompanying promise, “we will not compromise on our high environmental protection, animal welfare and food standards”. Earlier this month, they voted that measure out of the agriculture bill. US companies are aggressively demanding access to the NHS. The talks will be extremely complex and incomprehensible to almost everyone. There will be plenty of opportunities to give them what they want while fooling voters.

Boris Johnson’s central mission, overseen by Dominic Cummings, is to break down all barriers between government and the power of money. It is to allow private interests to intrude into the very heart of government, while marginalising the civil service. This helps to explain why Johnson is so reluctant to let Cummings go. The disasters of the past few weeks hint at the likely results.

Wednesday, 8 April 2020

Defining productivity in a pandemic may teach us a lesson

How should we measure the contribution of a teacher or a health worker during this crisis asks DIANE COYLE in The FT

One “P” word has been dominating economic policy discussions for some time now: not “pandemic”, but “productivity”. Now that coronavirus has dealt an unprecedented blow to economies everywhere, policymakers are asking how it will affect productivity at a national level.

The long-term effects of Covid-19 are unknown — they depend on the length of time for which economic activity will have to be suspended. The longer lockdowns last, the greater the hit to output growth and increasing unemployment.

Productivity — the output the economy gains for the resources and effort it expends — matters because it is what drives improvements in living standards: better health; longer lives; greater comfort. Investment, innovation and skills are the key ingredients, though the recipe is still a mystery.

In the UK, the pandemic will certainly cause a short-term fall in private-sector productivity. This is not only because many people are unwell or struggling to work at home around children and pets, but also because of a sharp decline in output. Employment is falling too, but many businesses are keeping workers on their books so labour input will not decline by as much. In general, productivity falls when output falls.

In the public sector, measuring productivity is hard. For services such as health and education, the Office for National Statistics looks at both activity and quality — such as the number of pupils and their exam grades, or the number of operations and health outcomes. But, at the best of times, these measures depend on other factors.

How should we think of the productivity of a teacher preparing lessons for online delivery, with all the challenges that involves, and what will be the effect on pupils’ attainment? It is easy to think of new measures, such as the number of online lessons delivered, but hard to imagine pupil outcomes not suffering.

As for medical staff, who would argue their productivity has not rocketed in recent weeks? But for many patients the outcomes that are measured will sadly be tragic. The biggest “productivity” boost may come from a new vaccine.

Public investment in infrastructure or green technologies will ultimately help productivity, but financial pain may force businesses to retrench. Business investment in the UK has been sluggish anyway, falling in 2018 and rising just 0.6 per cent in 2019. It is hard to foresee anything other than a big fall from the £50m-or-so-a-quarter last year.

Will supply chains unravel? The division of labour and specialisation that comes with outsourcing has driven gains in manufacturing productivity since the 1980s, but it depends on frictionless logistics and freight. Keeping that system going through lockdowns will take significant international co-ordination, which seems unlikely.

Some recent work suggests that even quite small shocks can cause networks to fall apart. This one will reverberate as waves of contagion hit countries at varying times. One response would be for importing companies to diversify supply chains. A less benign one — in productivity terms — would be a shift to reshoring production at home.

The pandemic and its aftermath will raise profound questions. Productivity involves a more-for-less (or, at least, more-for-the-same) mindset — hence the just-in-time systems and tight logistics operations. Companies may rethink the need for buffers as economic insurance. Inventories could rise, increasing business costs. Suppliers closer to home could be found, again at higher cost.

Perhaps the definition of economic wellbeing will also change. Conventional economic output matters, as people now losing their incomes know all too well. But so do social support networks and fair access to services. Without them, everyone is more vulnerable. Prosperity is more than productivity.

One “P” word has been dominating economic policy discussions for some time now: not “pandemic”, but “productivity”. Now that coronavirus has dealt an unprecedented blow to economies everywhere, policymakers are asking how it will affect productivity at a national level.

The long-term effects of Covid-19 are unknown — they depend on the length of time for which economic activity will have to be suspended. The longer lockdowns last, the greater the hit to output growth and increasing unemployment.

Productivity — the output the economy gains for the resources and effort it expends — matters because it is what drives improvements in living standards: better health; longer lives; greater comfort. Investment, innovation and skills are the key ingredients, though the recipe is still a mystery.

In the UK, the pandemic will certainly cause a short-term fall in private-sector productivity. This is not only because many people are unwell or struggling to work at home around children and pets, but also because of a sharp decline in output. Employment is falling too, but many businesses are keeping workers on their books so labour input will not decline by as much. In general, productivity falls when output falls.

In the public sector, measuring productivity is hard. For services such as health and education, the Office for National Statistics looks at both activity and quality — such as the number of pupils and their exam grades, or the number of operations and health outcomes. But, at the best of times, these measures depend on other factors.

How should we think of the productivity of a teacher preparing lessons for online delivery, with all the challenges that involves, and what will be the effect on pupils’ attainment? It is easy to think of new measures, such as the number of online lessons delivered, but hard to imagine pupil outcomes not suffering.

As for medical staff, who would argue their productivity has not rocketed in recent weeks? But for many patients the outcomes that are measured will sadly be tragic. The biggest “productivity” boost may come from a new vaccine.

Public investment in infrastructure or green technologies will ultimately help productivity, but financial pain may force businesses to retrench. Business investment in the UK has been sluggish anyway, falling in 2018 and rising just 0.6 per cent in 2019. It is hard to foresee anything other than a big fall from the £50m-or-so-a-quarter last year.

Will supply chains unravel? The division of labour and specialisation that comes with outsourcing has driven gains in manufacturing productivity since the 1980s, but it depends on frictionless logistics and freight. Keeping that system going through lockdowns will take significant international co-ordination, which seems unlikely.

Some recent work suggests that even quite small shocks can cause networks to fall apart. This one will reverberate as waves of contagion hit countries at varying times. One response would be for importing companies to diversify supply chains. A less benign one — in productivity terms — would be a shift to reshoring production at home.

The pandemic and its aftermath will raise profound questions. Productivity involves a more-for-less (or, at least, more-for-the-same) mindset — hence the just-in-time systems and tight logistics operations. Companies may rethink the need for buffers as economic insurance. Inventories could rise, increasing business costs. Suppliers closer to home could be found, again at higher cost.

Perhaps the definition of economic wellbeing will also change. Conventional economic output matters, as people now losing their incomes know all too well. But so do social support networks and fair access to services. Without them, everyone is more vulnerable. Prosperity is more than productivity.

Wednesday, 12 December 2018

How one man’s story exposes the myths behind our migration stereotypes

Robert, a Romanian law graduate, didn’t come to the UK to undercut wages. But he ended up in insecure low-paid work writes Aditya Chakrabortty in The Guardian

The best way to defeat a crass generalisation is with specifics, and what Robert’s story tells you is it’s not the migrant worker doing the undercutting here. He even tries to get his British-born workmates to join him in a class action for what’s rightfully theirs. The real problem is instead the imbalance of power between the worker and the employer, which is happily maintained by the same politicians today who claim they want to help the “left behind”.

PMP and the 18,000 or so other employment agencies in Britain are overseen by a government inspectorate of just 11 staff. The director of labour market enforcement in the UK, David Metcalf, admits that a UK employer is likely to be inspected by his team only once every 500 years. Were I an unscrupulous boss, I would take one look at those numbers and ask myself: if I do my worst, what’s the worst that can happen?

What keeps Robert here now is those weekends with his daughter. But after 10 years in Britain he’s learned something else too, about the reality of a country that claims to welcome foreigners, even as they punish them. An economy that promises a better life to those it then sucks dry. A society that kids itself that it’s a soft touch when really, it is as cold and hard as any interminable overnight shift.

Anti-Brexit protesters in November. ‘The likes of Robert make the easiest human punchbags. You rarely see him or the millions of other EU citizens living in Britain on your TV.’ Photograph: Daniel Leal-Olivas/AFP/Getty Images

Amid all the true-blue backbench blowhards and armchair pundits who will occupy the airwaves this Brexit week, one thing is guaranteed: you won’t hear a word from Robert. Why should you? He commands neither power nor status. He has hardly any money either. And yet he is crucial to this debate, because it is people like him that Brexit Britain wants to shut out.

Robert is a migrant, under a prime minister who keeps trying and failing to impose an arbitrary cap on migrants to this country. Born in Timişoara, Romania, he now lives in a democracy that barely batted an eyelid when Nigel Farage said it was OK to be worried about Romanian neighbours. And Robert gets all the brickbats hurled at foreigners down the ages – that he’s only here to take your jobs and claim your benefits (at one and the same time, mystifyingly), to undercut your wages and give nothing back.

What’s left is a 38-year-old tearing himself apart over his broken life. ‘I’m an idiot,' he says. ‘I’ve wasted myself.'

The likes of Robert make the easiest human punchbags. You rarely see him or the millions of other EU citizens living in Britain on your TV. Nor do you hear about them from a political class forever chuntering on about the will of the people, yet too aloof from the people to know who they are or what they want, and too scared of them to engage in dialogue.

Yet Robert (he’s asked that his surname be withheld) is no caricature. It’s not just how he dotes on his daughter and has a streak of irony thicker than the coffee he serves up. It’s also how his life in Britain proves that those declaimed causes of Brexit are both too easy and too far off the mark. However sad his story, it also shows where our economy really is broken – and how it will not be fixed by kicking out migrants.

We met a few weeks ago at his flat on the outskirts of Newcastle upon Tyne. Too bare to be a home, its sole reminder of his old family life is a little girl’s bedroom, kept in unchildlike order for his daughter’s weekend visits. He and his wife split a few months ago, he says, when the family’s money ran out. What’s left now is a bank account in almost permanent overdraft and a 38-year-old man tearing himself apart over his broken life here. “I’m an idiot,” he says. “I’ve wasted myself.”

But please, spare him the migrant stereotypes. Low-skilled? Robert came to the UK in 2008 with a law degree and speaking three languages. Low aspirations? Even while grafting in restaurants and hotels, he fired off over 100 applications for a solicitor’s training contract. That yielded just one interview, in Leeds. Local firms that were happy to have him volunteer for free proved more reluctant to give him a paying job. He ended up in a part of the country that has spent most of the past 40 years trying to recover from Thatcherism’s devastation, and which is even now paying the price in cuts for the havoc wreaked 10 years ago by bankers largely based hundreds of miles away. In a country where relations between regions are as lopsided as they are between workers and bosses, the odds were stacked against him from the start.

Finally, Robert signed with a temp agency, PMP Recruitment, which in August 2012 placed him with the local Nestlé factory. And that’s where trouble really began.

He had just enrolled in the precarious workforce, which at the last count numbered just over 3.8 million workers across the UK. Never guaranteed work, he had to wait for the offer of shifts to be texted to him a few days beforehand. He did days, nights, whatever was given, and started on the minimum wage in Nestlé’s Fawdon plant – a giant place churning out Toffee Crisps and Rolos and Fruit Pastilles. It was no Willy Wonka-land.

Robert began by “spotting” – standing on a podium overlooking the Blue Riband production line and pulling out imperfect chocolate bars. Seeing the conveyor belt spool along for hours on end made him dizzy, and another recently departed worker tells me he couldn’t bear to do it for long (Nestlé says it has “rotation processes for work that is particularly repetitive”). Stubborn pride made him stick it out for 12-hour shifts. “Leave your head at home,” workmates would advise and, amid the exhaustion of shifts and raising a family, that’s what he did. But bit by bit he noticed things were wrong.

As an agency worker, he says he was doing the same tasks as Nestlé staff, but for less money. They got a pay rise, he alleges, that agency workers didn’t. He would do work classed by the company as “skilled” but instead got “unskilled” rates. His former workmate, who doesn’t wish to be named, tells me this was common practice: “If Nestlé wanted you to come in at an awkward time, they’d say, ‘We can pay you skilled rates’.” Over the years, Robert estimates that he lost out on about £26,000 of income.

Robert was in no man’s land. He was spending his days working for Nestlé but was not their direct employee – even though he gave five years of service at Fawdon. Nor did he have much to do with his recruiters at PMP, a nationwide agency. As for the plant’s trade unions, he saw them as “a waste of space”. He was trapped in an institutional vacuum. The chair of the Law Society’s employment law committee, Max Winthrop, describes such arrangements – working for one company while on the books of another for years on end – as a “fiction”. “The most generous way you can look at it is, it’s a confusing situation. The least generous is that it’s a deliberate attempt to throw sand in everyone’s eyes so we can’t see the true nature of the relationship.” Nestlé says that of its 600 staff at Fawdon, 100 are agency, all via PMP. Over the years, Robert says he saw hundreds of agency staff come and go.

When Robert raised the issue with Nestlé managers, he alleges that shifts were no longer given to him. Finally, just before last Christmas, he resigned. He then tried to get other agency workers to join him in taking Nestlé to court, but they were, he says, “too nervous”. So he launched an employment tribunal case alone and, a few weeks after we met, Nestlé settled out of court. One of the conditions of the settlement is that he cannot discuss it, but Robert knows this article will appear. Citing confidentiality, Nestlé did not want to comment directly on his case but says that, since 2014, all staff in its factories get the living wage, and “we refute any allegation that working conditions at our Fawdon factory are below standard”.

On his PMP payslips Robert also noticed that – as a result of the “recruitment travel scheme” in which the agency had enrolled him – some months he was getting less than minimum wage, a situation for which Winthrop says he “cannot find any justification”. He took PMP to court too, and a couple of months ago was awarded over £2,000 in back pay. PMP wouldn’t comment for this piece, other than to say it is appealing the verdict.

Amid all the true-blue backbench blowhards and armchair pundits who will occupy the airwaves this Brexit week, one thing is guaranteed: you won’t hear a word from Robert. Why should you? He commands neither power nor status. He has hardly any money either. And yet he is crucial to this debate, because it is people like him that Brexit Britain wants to shut out.

Robert is a migrant, under a prime minister who keeps trying and failing to impose an arbitrary cap on migrants to this country. Born in Timişoara, Romania, he now lives in a democracy that barely batted an eyelid when Nigel Farage said it was OK to be worried about Romanian neighbours. And Robert gets all the brickbats hurled at foreigners down the ages – that he’s only here to take your jobs and claim your benefits (at one and the same time, mystifyingly), to undercut your wages and give nothing back.

What’s left is a 38-year-old tearing himself apart over his broken life. ‘I’m an idiot,' he says. ‘I’ve wasted myself.'

The likes of Robert make the easiest human punchbags. You rarely see him or the millions of other EU citizens living in Britain on your TV. Nor do you hear about them from a political class forever chuntering on about the will of the people, yet too aloof from the people to know who they are or what they want, and too scared of them to engage in dialogue.

Yet Robert (he’s asked that his surname be withheld) is no caricature. It’s not just how he dotes on his daughter and has a streak of irony thicker than the coffee he serves up. It’s also how his life in Britain proves that those declaimed causes of Brexit are both too easy and too far off the mark. However sad his story, it also shows where our economy really is broken – and how it will not be fixed by kicking out migrants.

We met a few weeks ago at his flat on the outskirts of Newcastle upon Tyne. Too bare to be a home, its sole reminder of his old family life is a little girl’s bedroom, kept in unchildlike order for his daughter’s weekend visits. He and his wife split a few months ago, he says, when the family’s money ran out. What’s left now is a bank account in almost permanent overdraft and a 38-year-old man tearing himself apart over his broken life here. “I’m an idiot,” he says. “I’ve wasted myself.”

But please, spare him the migrant stereotypes. Low-skilled? Robert came to the UK in 2008 with a law degree and speaking three languages. Low aspirations? Even while grafting in restaurants and hotels, he fired off over 100 applications for a solicitor’s training contract. That yielded just one interview, in Leeds. Local firms that were happy to have him volunteer for free proved more reluctant to give him a paying job. He ended up in a part of the country that has spent most of the past 40 years trying to recover from Thatcherism’s devastation, and which is even now paying the price in cuts for the havoc wreaked 10 years ago by bankers largely based hundreds of miles away. In a country where relations between regions are as lopsided as they are between workers and bosses, the odds were stacked against him from the start.

Finally, Robert signed with a temp agency, PMP Recruitment, which in August 2012 placed him with the local Nestlé factory. And that’s where trouble really began.

He had just enrolled in the precarious workforce, which at the last count numbered just over 3.8 million workers across the UK. Never guaranteed work, he had to wait for the offer of shifts to be texted to him a few days beforehand. He did days, nights, whatever was given, and started on the minimum wage in Nestlé’s Fawdon plant – a giant place churning out Toffee Crisps and Rolos and Fruit Pastilles. It was no Willy Wonka-land.

Robert began by “spotting” – standing on a podium overlooking the Blue Riband production line and pulling out imperfect chocolate bars. Seeing the conveyor belt spool along for hours on end made him dizzy, and another recently departed worker tells me he couldn’t bear to do it for long (Nestlé says it has “rotation processes for work that is particularly repetitive”). Stubborn pride made him stick it out for 12-hour shifts. “Leave your head at home,” workmates would advise and, amid the exhaustion of shifts and raising a family, that’s what he did. But bit by bit he noticed things were wrong.

As an agency worker, he says he was doing the same tasks as Nestlé staff, but for less money. They got a pay rise, he alleges, that agency workers didn’t. He would do work classed by the company as “skilled” but instead got “unskilled” rates. His former workmate, who doesn’t wish to be named, tells me this was common practice: “If Nestlé wanted you to come in at an awkward time, they’d say, ‘We can pay you skilled rates’.” Over the years, Robert estimates that he lost out on about £26,000 of income.

Robert was in no man’s land. He was spending his days working for Nestlé but was not their direct employee – even though he gave five years of service at Fawdon. Nor did he have much to do with his recruiters at PMP, a nationwide agency. As for the plant’s trade unions, he saw them as “a waste of space”. He was trapped in an institutional vacuum. The chair of the Law Society’s employment law committee, Max Winthrop, describes such arrangements – working for one company while on the books of another for years on end – as a “fiction”. “The most generous way you can look at it is, it’s a confusing situation. The least generous is that it’s a deliberate attempt to throw sand in everyone’s eyes so we can’t see the true nature of the relationship.” Nestlé says that of its 600 staff at Fawdon, 100 are agency, all via PMP. Over the years, Robert says he saw hundreds of agency staff come and go.

When Robert raised the issue with Nestlé managers, he alleges that shifts were no longer given to him. Finally, just before last Christmas, he resigned. He then tried to get other agency workers to join him in taking Nestlé to court, but they were, he says, “too nervous”. So he launched an employment tribunal case alone and, a few weeks after we met, Nestlé settled out of court. One of the conditions of the settlement is that he cannot discuss it, but Robert knows this article will appear. Citing confidentiality, Nestlé did not want to comment directly on his case but says that, since 2014, all staff in its factories get the living wage, and “we refute any allegation that working conditions at our Fawdon factory are below standard”.

On his PMP payslips Robert also noticed that – as a result of the “recruitment travel scheme” in which the agency had enrolled him – some months he was getting less than minimum wage, a situation for which Winthrop says he “cannot find any justification”. He took PMP to court too, and a couple of months ago was awarded over £2,000 in back pay. PMP wouldn’t comment for this piece, other than to say it is appealing the verdict.

The best way to defeat a crass generalisation is with specifics, and what Robert’s story tells you is it’s not the migrant worker doing the undercutting here. He even tries to get his British-born workmates to join him in a class action for what’s rightfully theirs. The real problem is instead the imbalance of power between the worker and the employer, which is happily maintained by the same politicians today who claim they want to help the “left behind”.

PMP and the 18,000 or so other employment agencies in Britain are overseen by a government inspectorate of just 11 staff. The director of labour market enforcement in the UK, David Metcalf, admits that a UK employer is likely to be inspected by his team only once every 500 years. Were I an unscrupulous boss, I would take one look at those numbers and ask myself: if I do my worst, what’s the worst that can happen?

What keeps Robert here now is those weekends with his daughter. But after 10 years in Britain he’s learned something else too, about the reality of a country that claims to welcome foreigners, even as they punish them. An economy that promises a better life to those it then sucks dry. A society that kids itself that it’s a soft touch when really, it is as cold and hard as any interminable overnight shift.

Wednesday, 31 January 2018

Analysts caught off guard by 41% Capita share drop

Cat Rutter Pooley in The Financial Times

There may be some red-faced analysts across the City this morning.

Only two out of 16 analysts polled by Bloomberg had a sell rating on Capita before today, when its shares plummeted 41 per cent on a profit warning and planned £700m rights issue.

Of the rest, 11 had a hold rating and three a buy rating.

One of those buy recommendations came from Numis, which issued its note on the company two weeks ago.

Then, Numis described a meeting with the new Capita chief executive as “positive”, noting that:

It is easy to be critical of the past, but his observations on some of the structural and cultural issues at Capita highlighted some fundamental problems, but also material opportunities. We were encouraged by [Jonathan Lewis’s] comments on the need for great focus, cost reductions (whilst also re-investing for growth), and need to focus on cash.

Numis declined to comment immediately on whether it was reviewing the recommendation in light of the company’s update.

Jefferies, which has also had a ‘buy’ recommendation on the stock, characterised Wednesday’s announcement as a “kitchen sinking”, or effort to cram all the bad news out at once. The revelations could generate a 40 per cent decline in earnings expectations for the full year, it said, adding that the revenue environment remained “lacklustre”.

Shares are current trading around 210p, down 40 per cent.

Meanwhile, the ripples from Capita’s share price drop are leaking across the outsourcing industry. Serco slipped 3 per cent, and Mitie was down 2.4 per cent at pixel time.

There may be some red-faced analysts across the City this morning.

Only two out of 16 analysts polled by Bloomberg had a sell rating on Capita before today, when its shares plummeted 41 per cent on a profit warning and planned £700m rights issue.

Of the rest, 11 had a hold rating and three a buy rating.

One of those buy recommendations came from Numis, which issued its note on the company two weeks ago.

Then, Numis described a meeting with the new Capita chief executive as “positive”, noting that:

It is easy to be critical of the past, but his observations on some of the structural and cultural issues at Capita highlighted some fundamental problems, but also material opportunities. We were encouraged by [Jonathan Lewis’s] comments on the need for great focus, cost reductions (whilst also re-investing for growth), and need to focus on cash.

Numis declined to comment immediately on whether it was reviewing the recommendation in light of the company’s update.

Jefferies, which has also had a ‘buy’ recommendation on the stock, characterised Wednesday’s announcement as a “kitchen sinking”, or effort to cram all the bad news out at once. The revelations could generate a 40 per cent decline in earnings expectations for the full year, it said, adding that the revenue environment remained “lacklustre”.

Shares are current trading around 210p, down 40 per cent.

Meanwhile, the ripples from Capita’s share price drop are leaking across the outsourcing industry. Serco slipped 3 per cent, and Mitie was down 2.4 per cent at pixel time.

Wednesday, 17 January 2018

Carillion may have gone bust, but outsourcing is a powerful public good

John McTernan in The Guardian

What has outsourcing ever done for me?

In a parody of the Monty Python skit from Life of Brian, that is what critics and commentators are asking about the collapse of Carillion – formerly one of the UK’s biggest companies.

The answer – the true answer – is that we should always be grateful that private companies have delivered better public service for less money. And therefore have done three important things for us all.

First and foremost, it has delivered vital public services – and delivered them well. Notice that in the fallout over the collapse of Carillion few questioned the quality of what it has been doing in the public realm. From the NHS to HS2 the company’s record of delivery is positive.

Second, the company has taken risk out of the public sector and absorbed it themselves. It is one of the oldest criticism of public private partnerships that the transfer of risks is never achieved properly – profits, we are told sanctimoniously, are privatised, while risk remains nationalised. In the case of Carillion we can see that is utterly and demonstrably false. How? In the simplest possible way – the company has gone bust. There can be no starker demonstration that risk has been fully transferred than to see it crystallise – which has just happened.

And last, but not least, we have had a bargain – we have paid substantially less for services than they cost to deliver. How can we be sure about that? Again, it is the collapse that is the proof. If the directors had driven exploitative bargains with the public sector then they would be driving round in Maseratis rather than polishing their CVs and wondering how to explain their catastrophic failure to future prospective employers. Saving money in the provision of public services is a good thing. On the one hand, there are always too many demands to answer. On the other, at a time when the public books still have a massive overhang of debt following the Great Recession, every little bit of efficiency helps.

The problem is that we are all a little squeamish. Companies going out of business is part and parcel of how capitalism works – it is essential that there is both creativity and destruction. For individual workers whose pay and pensions depend on the continued success of the company that is disruptive.

But where public services are being delivered, government is continuing to underwrite employment and contracts will be taken over by another provider – public or private. This is, remember, the tightest labour market since the mid-70s. There is no reserve army of labour to take over these jobs at a lower price. After some turbulence, things will settle down again. Shareholders will have lost a lot of money. And senior managers will have lost jobs. Forgive me for not weeping over either of those facts.

The alternative is worse. Far worse. It is that repeated failure is bailed out – and, in effect, rewarded rather than punished. What does that look like? The life of the average government department. Millions of people are being immiserated by the failures of universal credit (UC). And this is not because of flaws in the new system but because of features of the new benefit. UC is failing and the only people paying the price are hard-working families who can least afford it.

The same is true of the Home Office. If the same combination of malignity, incompetence and out-and-out racism was being demonstrated by any private company it would not only be in court repeatedly, it would be bust. As it should be. The lack of contestability and accountability in direct government provision of services is a huge problem. Having a small amount of it brought into the system by contracting out is a powerful public good.

What has outsourcing ever done for me?

In a parody of the Monty Python skit from Life of Brian, that is what critics and commentators are asking about the collapse of Carillion – formerly one of the UK’s biggest companies.

The answer – the true answer – is that we should always be grateful that private companies have delivered better public service for less money. And therefore have done three important things for us all.

First and foremost, it has delivered vital public services – and delivered them well. Notice that in the fallout over the collapse of Carillion few questioned the quality of what it has been doing in the public realm. From the NHS to HS2 the company’s record of delivery is positive.

Second, the company has taken risk out of the public sector and absorbed it themselves. It is one of the oldest criticism of public private partnerships that the transfer of risks is never achieved properly – profits, we are told sanctimoniously, are privatised, while risk remains nationalised. In the case of Carillion we can see that is utterly and demonstrably false. How? In the simplest possible way – the company has gone bust. There can be no starker demonstration that risk has been fully transferred than to see it crystallise – which has just happened.

And last, but not least, we have had a bargain – we have paid substantially less for services than they cost to deliver. How can we be sure about that? Again, it is the collapse that is the proof. If the directors had driven exploitative bargains with the public sector then they would be driving round in Maseratis rather than polishing their CVs and wondering how to explain their catastrophic failure to future prospective employers. Saving money in the provision of public services is a good thing. On the one hand, there are always too many demands to answer. On the other, at a time when the public books still have a massive overhang of debt following the Great Recession, every little bit of efficiency helps.

The problem is that we are all a little squeamish. Companies going out of business is part and parcel of how capitalism works – it is essential that there is both creativity and destruction. For individual workers whose pay and pensions depend on the continued success of the company that is disruptive.

But where public services are being delivered, government is continuing to underwrite employment and contracts will be taken over by another provider – public or private. This is, remember, the tightest labour market since the mid-70s. There is no reserve army of labour to take over these jobs at a lower price. After some turbulence, things will settle down again. Shareholders will have lost a lot of money. And senior managers will have lost jobs. Forgive me for not weeping over either of those facts.

The alternative is worse. Far worse. It is that repeated failure is bailed out – and, in effect, rewarded rather than punished. What does that look like? The life of the average government department. Millions of people are being immiserated by the failures of universal credit (UC). And this is not because of flaws in the new system but because of features of the new benefit. UC is failing and the only people paying the price are hard-working families who can least afford it.

The same is true of the Home Office. If the same combination of malignity, incompetence and out-and-out racism was being demonstrated by any private company it would not only be in court repeatedly, it would be bust. As it should be. The lack of contestability and accountability in direct government provision of services is a huge problem. Having a small amount of it brought into the system by contracting out is a powerful public good.

Carillion collapse a ‘watershed’ for outsourcing

George Parker and Gemma Tetlow in The Financial Times

The collapse of Carillion, the company responsible for everything from building hospitals to providing school meals, is a “watershed” moment that proves that the private sector should not be running swaths of Britain’s public services, according to Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn.

The collapse of Carillion, the company responsible for everything from building hospitals to providing school meals, is a “watershed” moment that proves that the private sector should not be running swaths of Britain’s public services, according to Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn.

The revolution in outsourcing public services started by Margaret Thatcher, which by 2014-15 accounted for about £100bn or 15 per cent of public spending according to the National Audit Office, faces a thorough reappraisal, with Mr Corbyn standing ready to disrupt the industry altogether.

“It is time to put an end to the rip-off privatisation policies . . . that fleeced the public of billions of pounds,” said Mr Corbyn, in a video that was watched almost 300,000 times in 24 hours on Facebook.

“Across the public sector, the outsource-first dogma has wreaked havoc. Often it is the same companies that have gone from service to service, creaming off profits and failing to deliver the quality of service our people deserve,” he added.

Outsourcing of public services to the private sector was virtually non-existent in the 1970s, but Mrs Thatcher changed that in 1980 when local authorities — which had previously directly employed blue-collar workers to build roads and houses, and collect refuse — were required to put the work out to tender.

David Willetts, a former Treasury official, policy wonk and later Tory MP, was a key promoter of the private finance initiative, but admits that in some recent projects the scheme has gone awry.

He argues that it was right to hand projects to the private sector if there was a genuine transfer of risk, but that the Carillion collapse had exposed cases where in the end, the risk reverted to the government, which had to maintain public services.

Last year John McDonnell, shadow chancellor, vowed at the Labour conference to nationalise such contracts as part of a wider plan to roll back private sector involvement in public services. Carillion has strengthened his resolve.

In a more detailed email briefing, the party’s position seemed more nuanced. It said Labour would “look to” take control of PFI contracts and that it would review all of them and — “if necessary” — take them back in-house.

This has unsettled some Labour moderates. “Where is the element of choice if everything is done in house by a public sector body?” asked one Blairite former minister. “Could things be done differently? All that would be lost.”

Since 1980 huge swaths of services — from providing school meals to refuelling RAF aircraft — have been outsourced to the private sector under Conservative and Labour governments.

This outsourcing boom led to the creation of new companies, such as Capita, that specialise in serving public sector clients but it also attracted existing overseas municipal providers, such as Veolia.

NAO figures suggest the bulk of central government spending on outsourcing goes to pay for IT, facilities management and professional services. Local authorities rely on the private sector to provide a range of services from social care to waste disposal, and the private sector provides healthcare to NHS-funded patients.

Several high-profile outsourcing failures have raised questions about whether the taxpayer is getting best value for money from some contracts. Carillion’s collapse is the most recent, but not the only example.

Members of the armed forces were drafted in to provide security for the 2012 London Olympic Games after G4S was unable to provide sufficient numbers of staff.

The failure of Metronet, which had been contracted to maintain and upgrade the London Underground, in 2007 cost the taxpayer at least £170m. Several privately run prisons have hit the headlines over the past 18 months as levels of violence have increased while spending and staff have been cut.

But many other public services have been successfully outsourced with little or no public comment.

“Most people in Britain are endlessly using contracted-out services without really noticing it,” said Tony Travers, a professor at the London School of Economics. “The question is what is the contract mechanism to ensure that what is done is done appropriately.”

He said at least two lessons could be drawn from recent failures. The first is that overzealous efforts by government to drive down costs in contracts are not necessarily a good thing.

Carillion is not the only private provider to have signed up to contracts committing to providing services at implausibly low cost. At the end of last year, the Competition and Markets Authority highlighted concern that private providers of social care that serve mainly the public sector were “unlikely to be sustainable” unless local authorities paid more for their services.

The second lesson is that ministers and civil servants need to carry out proper due diligence on companies tendering for public contracts.

Thursday, 25 May 2017

London School of Economics - Shame on you

Owen Jones in The Guardian

It is a university that prides itself on being a forum for debate about social injustice and inequality. The London School of Economics was founded by Fabian socialists at the end of the 19th century: they believed education was key to liberating society from social ills.

Last week I was due to attend a debate at the LSE on the expansion of secondary moderns (which is what selection in education really means). At the request of cleaners on strike over their terms and conditions, I withdrew at the last minute. And here is the perverse truth: well-paid speakers will turn up at this prestigious institution to debate the great injustices of modern Britain. Then in come the cleaners – all from migrant or minority backgrounds – to clear up, victims of some of the very injustices that have just been debated.

Like most universities, LSE outsourced its cleaners years ago. It’s cheaper, you see, because the cleaners can then be employed with worse terms and conditions than in-house staff. In this way a university with a multimillion-pound budget can deviously save money on those who clean the libraries, the lecture halls, the offices.

An in-house LSE worker has up to 41 days’ paid leave, six months’ fully paid sick pay, and good maternity pay and pension rights. Cleaners, on the other hand, have the statutory minimum. If they fall ill, they are paid nothing for the first three days, then just £17.87 a day. For a cleaner paid £9.75 an hour – living in one of the world’s most expensive cities – that’s simply not an option. “They can’t afford to be sick,” says Petros Elia, general secretary of the United Voices of the World (UVW) union. Cleaners turn up ill to work instead.

No wonder they describe themselves as “second-class”, “third-class”, or “no-class” workers. The response of LSE’s management is a sobering indictment of industrial relations in a society in which the employers have the whip hand. Cleaners and their supporters have been threatened with arrests and injunctions. “LSE’s mottos is ‘to know the causes of things’,” says Michael Etheridge, the Unison branch secretary, “and yet on the issue of outsourcing it has, as an institution, been wholly ignorant.”

That these cleaners have stood up for themselves – in the face of such hostility – is courageous, and an inspiring precedent for other workers in low-paid, insecure Britain. They’ve come from a variety of different countries; some have only worked at LSE for a few months. But they have organised, and thrown themselves into a determined struggle that now has the university authorities on the run.

Rattled, the LSE has been forced to offer concessions: beginning with 10 days’ full sick pay, then 15, then 20. But UVW and Unison – which represents some of the other cleaners – are clear. This is not a strike simply about improved conditions: it is about being treated the same as other workers. Only parity will do. Unison has been offered a package of improvements, including sick pay of up to 65 days and four weeks of additional maternity pay, and a pledge to work “to reach full parity … in the near future”. But continued pressure on LSE to accept the cleaners’ demands is clearly necessary.

It is a saga that tells many stories about modern Britain. It’s about how, disproportionately, some of the lowest paid and most insecure work is done by migrants and minorities. It’s about a race to the bottom in terms and conditions. It’s about how the law is rigged in favour of bosses. But it’s also about how – with determination and organisation – workers can indeed win.

Mildred Simpson was born in Jamaica and moved to Britain in 1989: she’s worked at the LSE for 16 years. A few years ago she was made a supervisor: back then, there were 25 supervisors, but the number has been slashed to 13. For no extra pay, she is expected to do the jobs of two people. This, for her, is a fight for equality. “We’re doing all the dirty work while they’re drinking their champagne and drinking their coffee,” she says. But she has a message to other workers too. “Fight as well as us as much as you can, for your rights, for pensions, for better working conditions, to be recognised.”

Britain’s universities grant their management lavish salaries: the Former LSE director Craig Calhoun was on a salary package of £381,000 a year and spent tens of thousands on overseas trips. It’s not just cleaners who are mistreated. Academia is becoming increasingly casualised and insecure. At Birmingham University, for instance, a shocking 70% of staff are on insecure contracts. Academics are overworked, struggling with bureaucracy, and often lacking the basic security of knowing how many hours they’re working each week.

Unions have been dramatically weakened in Britain. That has fed into a general sense that injustice is permanent, a fact of life like a weather system, rather than the consequence of human decisions. If there is no apparent collective means available to overcome injustice, then inevitably we become resigned. But if some marginalised, hitherto voiceless cleaners can put one of the world’s most prestigious universities on the backfoot, they set an example to others. This is a country that has endured the longest squeeze in wages for generations, while wealth at the top and in the boardroom has boomed; where our workforce is increasingly stripped of security and fundamental rights. That might be the current direction of travel, but it can be changed. And those cleaners at LSE show how.

It is a university that prides itself on being a forum for debate about social injustice and inequality. The London School of Economics was founded by Fabian socialists at the end of the 19th century: they believed education was key to liberating society from social ills.

Last week I was due to attend a debate at the LSE on the expansion of secondary moderns (which is what selection in education really means). At the request of cleaners on strike over their terms and conditions, I withdrew at the last minute. And here is the perverse truth: well-paid speakers will turn up at this prestigious institution to debate the great injustices of modern Britain. Then in come the cleaners – all from migrant or minority backgrounds – to clear up, victims of some of the very injustices that have just been debated.

Like most universities, LSE outsourced its cleaners years ago. It’s cheaper, you see, because the cleaners can then be employed with worse terms and conditions than in-house staff. In this way a university with a multimillion-pound budget can deviously save money on those who clean the libraries, the lecture halls, the offices.

An in-house LSE worker has up to 41 days’ paid leave, six months’ fully paid sick pay, and good maternity pay and pension rights. Cleaners, on the other hand, have the statutory minimum. If they fall ill, they are paid nothing for the first three days, then just £17.87 a day. For a cleaner paid £9.75 an hour – living in one of the world’s most expensive cities – that’s simply not an option. “They can’t afford to be sick,” says Petros Elia, general secretary of the United Voices of the World (UVW) union. Cleaners turn up ill to work instead.

No wonder they describe themselves as “second-class”, “third-class”, or “no-class” workers. The response of LSE’s management is a sobering indictment of industrial relations in a society in which the employers have the whip hand. Cleaners and their supporters have been threatened with arrests and injunctions. “LSE’s mottos is ‘to know the causes of things’,” says Michael Etheridge, the Unison branch secretary, “and yet on the issue of outsourcing it has, as an institution, been wholly ignorant.”

That these cleaners have stood up for themselves – in the face of such hostility – is courageous, and an inspiring precedent for other workers in low-paid, insecure Britain. They’ve come from a variety of different countries; some have only worked at LSE for a few months. But they have organised, and thrown themselves into a determined struggle that now has the university authorities on the run.

Rattled, the LSE has been forced to offer concessions: beginning with 10 days’ full sick pay, then 15, then 20. But UVW and Unison – which represents some of the other cleaners – are clear. This is not a strike simply about improved conditions: it is about being treated the same as other workers. Only parity will do. Unison has been offered a package of improvements, including sick pay of up to 65 days and four weeks of additional maternity pay, and a pledge to work “to reach full parity … in the near future”. But continued pressure on LSE to accept the cleaners’ demands is clearly necessary.

It is a saga that tells many stories about modern Britain. It’s about how, disproportionately, some of the lowest paid and most insecure work is done by migrants and minorities. It’s about a race to the bottom in terms and conditions. It’s about how the law is rigged in favour of bosses. But it’s also about how – with determination and organisation – workers can indeed win.

Mildred Simpson was born in Jamaica and moved to Britain in 1989: she’s worked at the LSE for 16 years. A few years ago she was made a supervisor: back then, there were 25 supervisors, but the number has been slashed to 13. For no extra pay, she is expected to do the jobs of two people. This, for her, is a fight for equality. “We’re doing all the dirty work while they’re drinking their champagne and drinking their coffee,” she says. But she has a message to other workers too. “Fight as well as us as much as you can, for your rights, for pensions, for better working conditions, to be recognised.”

Britain’s universities grant their management lavish salaries: the Former LSE director Craig Calhoun was on a salary package of £381,000 a year and spent tens of thousands on overseas trips. It’s not just cleaners who are mistreated. Academia is becoming increasingly casualised and insecure. At Birmingham University, for instance, a shocking 70% of staff are on insecure contracts. Academics are overworked, struggling with bureaucracy, and often lacking the basic security of knowing how many hours they’re working each week.

Unions have been dramatically weakened in Britain. That has fed into a general sense that injustice is permanent, a fact of life like a weather system, rather than the consequence of human decisions. If there is no apparent collective means available to overcome injustice, then inevitably we become resigned. But if some marginalised, hitherto voiceless cleaners can put one of the world’s most prestigious universities on the backfoot, they set an example to others. This is a country that has endured the longest squeeze in wages for generations, while wealth at the top and in the boardroom has boomed; where our workforce is increasingly stripped of security and fundamental rights. That might be the current direction of travel, but it can be changed. And those cleaners at LSE show how.

Tuesday, 20 December 2016

The Problem is Free Trade not Free Movement

Ian Allinson in The Guardian

While freedom of movement has been a hot topic since the debates around Brexit began, few would have predicted it would become such a focus in the Unite general secretary election, in which I’m standing.

Anger around jobs and conditions is justified, but often misdirected. Neoliberal capitalism has been disastrous. Free trade deals enshrine the rights of capital while ignoring the needs of humans and our warming planet. Workers have been dumped out of jobs by the million, work has intensified, workers feel more vulnerable to managerial whim, the share of wealth going to wages has fallen, welfare systems have been slashed and huge areas of life – including education, health and housing – are increasingly commoditised, all while our limited democracy is increasingly hollowed out.

Migrants are prime scapegoats for many politicians and media. Some employers provide fertile material for racists and nationalists. Fujitsu, my own employer, proposes to cut 1,800 UK jobs, hoping to boost profits by offshoring jobs to low-paid countries. Fujitsu is even asking some workers to train their replacements, brought to the UK to learn the job. Workers are being asked to dig their own graves.

When our livelihoods are threatened, workers sometimes respond by claiming privileged access to jobs, housing, and so on, and excluding others on the basis of gender, race or nationality. This is tempting because it sometimes “works” for some people for a short time. But it is misguided. If some workers try to protect their interests at the expense of others, the unity we need to win is undermined and we all lose.

Gerard Coyne is also standing for the general secretary post and his silence on this question, as on so many others, is deafening; meanwhile his relationships with the Labour right are worrying.

Len McCluskey, the present general secretary, though anti-racist, has fudged on workers’ freedom of movement, wrongly conceding ground to racists and nationalists. Just before the EU referendum McCluskey referred to it as an experiment at UK workers’ expense. As a delegate to the Unite conference shortly after the referendum, I moved a motion defending freedom of movement. Unite’s leadership opposed it, with their own motion calling for debate on the question. McCluskey now boasts that he has led this debate “demanding safeguards for workers, communities and industries affected by migration policy driven by greedy bosses”. Beyond dog-whistle politics, what does this mean?

McCluskey explained in a speech for the thinktank Class (Centre for Labour and Social Studies) that his “proposal is that any employer wishing to recruit labour abroad can only do so if they are either covered by a proper trade union agreement, or by sectoral collective bargaining”. All jobs should be covered by union agreements, but union weakness means most are not, and this applies especially to industries in which migrants have to work.

What would McCluskey’s proposal mean in practice? What would count as recruiting abroad? How long would a worker have to be in the UK before they could apply for an un-unionised job?

Giving different rights to different workers based on their nationality is discriminatory and divisive. It undermines solidarity. Blocking employers hiring on the basis of nationality would repeat the mistake of some trade unionists of a previous generation who sought to control the labour supply by excluding women from some jobs, fearing “they” would push down “our” wages. We, Unite’s membership, like the working class as a whole, come from all over the world. This is a strength, not a weakness.

It is free trade, not free movement of people, that has been a disaster for working-class people. Manufacturing has seen colossal job losses in recent decades as production has moved to countries in the south and east. Too often unions have responded by making common cause with the very employers sacking their members, against the foreign competition.

This approach has failed to protect jobs. Whether it is an employer threatening to dismiss and re-engage the same workers on lower pay (like the Durham teaching assistants), replacing workers with cheaper ones in the same workplace, or moving the jobs halfway round the world, workers are right to fight the degradation of employment. You can’t do that in partnership with the employer who is sacking you.

Thankfully workers are not always paralysed by the confusion of their leaders. Unite members at Capita and Prudential won important victories against offshoring. Members at the Fawley oil refinery spurned British Jobs For British Workers slogans and built solidarity to win equal pay for workers of all nationalities instead of trying to restrict the employment of migrants. Inspired by the Prudential win, industrial action in my own workplace currently includes refusal to cooperate with projects to move work offshore.

Unions should be following Fawley workers in demanding everyone is paid the rate for the job, regardless of employer, employment status, or nationality. We should be demanding full pay transparency, monitored by the unions. We should be calling for all jobs to be openly advertised, with no discrimination in hiring based on nationality. And existing workers should refuse to cooperate with handing over work unless their employment is assured.

The labour movement needs to regain the confidence to demand solutions that meet human needs, even when that upsets big business. We won’t do that by turning workers against each other on nationalist grounds, or by fudging the issue.

No general secretary candidate should chase votes by undermining the unity members need to defend their jobs. I am calling on Len McCluskey and Gerard Coyne to join me in championing workers’ rights to move freely (not just within the EU) and opposing any employment restrictions based on nationality.

While freedom of movement has been a hot topic since the debates around Brexit began, few would have predicted it would become such a focus in the Unite general secretary election, in which I’m standing.

Anger around jobs and conditions is justified, but often misdirected. Neoliberal capitalism has been disastrous. Free trade deals enshrine the rights of capital while ignoring the needs of humans and our warming planet. Workers have been dumped out of jobs by the million, work has intensified, workers feel more vulnerable to managerial whim, the share of wealth going to wages has fallen, welfare systems have been slashed and huge areas of life – including education, health and housing – are increasingly commoditised, all while our limited democracy is increasingly hollowed out.

Migrants are prime scapegoats for many politicians and media. Some employers provide fertile material for racists and nationalists. Fujitsu, my own employer, proposes to cut 1,800 UK jobs, hoping to boost profits by offshoring jobs to low-paid countries. Fujitsu is even asking some workers to train their replacements, brought to the UK to learn the job. Workers are being asked to dig their own graves.

When our livelihoods are threatened, workers sometimes respond by claiming privileged access to jobs, housing, and so on, and excluding others on the basis of gender, race or nationality. This is tempting because it sometimes “works” for some people for a short time. But it is misguided. If some workers try to protect their interests at the expense of others, the unity we need to win is undermined and we all lose.

Gerard Coyne is also standing for the general secretary post and his silence on this question, as on so many others, is deafening; meanwhile his relationships with the Labour right are worrying.

Len McCluskey, the present general secretary, though anti-racist, has fudged on workers’ freedom of movement, wrongly conceding ground to racists and nationalists. Just before the EU referendum McCluskey referred to it as an experiment at UK workers’ expense. As a delegate to the Unite conference shortly after the referendum, I moved a motion defending freedom of movement. Unite’s leadership opposed it, with their own motion calling for debate on the question. McCluskey now boasts that he has led this debate “demanding safeguards for workers, communities and industries affected by migration policy driven by greedy bosses”. Beyond dog-whistle politics, what does this mean?

McCluskey explained in a speech for the thinktank Class (Centre for Labour and Social Studies) that his “proposal is that any employer wishing to recruit labour abroad can only do so if they are either covered by a proper trade union agreement, or by sectoral collective bargaining”. All jobs should be covered by union agreements, but union weakness means most are not, and this applies especially to industries in which migrants have to work.

What would McCluskey’s proposal mean in practice? What would count as recruiting abroad? How long would a worker have to be in the UK before they could apply for an un-unionised job?

Giving different rights to different workers based on their nationality is discriminatory and divisive. It undermines solidarity. Blocking employers hiring on the basis of nationality would repeat the mistake of some trade unionists of a previous generation who sought to control the labour supply by excluding women from some jobs, fearing “they” would push down “our” wages. We, Unite’s membership, like the working class as a whole, come from all over the world. This is a strength, not a weakness.