Sarah O'Connor in The FT

Britain is sick. The number of people claiming disability benefits has doubled in a year. Working-age deaths (that did not involve Covid-19) are on the rise. As Andy Haldane, former chief economist of the Bank of England, put it in a speech recently: “For the first time, probably since the Industrial Revolution . . . health and wellbeing are in retreat”.

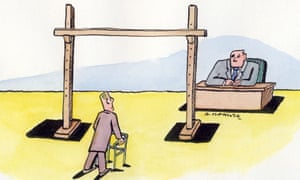

The consequences for the country’s economy have been well chewed over. A rising share of people are now too unwell to work, which makes it harder to tame inflation and boost growth. Understandably, then, “How can we get people back to work?” is the question policymakers keep asking. But what if work itself is part of the problem?

By many metrics, work is less dangerous to our health than it used to be, especially in a country like the UK where the manufacturing and mining sectors have shrunk so much. Musculoskeletal disorders, which used to be the biggest cause of work-related ill-health, have declined steadily over the past few decades.

But while work has become less physically dangerous, it seems to have become more psychologically dangerous. Work-related stress, depression and anxiety began to rise about a decade ago. This surged during the pandemic and now accounts for half of all work-related illness.

Why might that be? We know from government-sponsored survey data that there has been an intensification of work in recent decades across all types of jobs from delivery drivers to corporate lawyers. People are more likely now than in the 1990s to say they work fast and hard to tight deadlines.

There has also been a drop in the level of control people have over how they work, particularly among lower-paid workers. Between 1992 and 2017, the share of low-paid workers who report that they have a say in decisions which affect their work fell from 44 per cent to 27 per cent, with particularly steep drops among hospitality and retail workers.

Research shows the combination of high demands and low control at work — known in the academic literature as “job strain” — is bad for mental and physical health. One US study, which followed more than 52,000 working women over four years, found that job strain was associated with a greater increase in body mass index, for example.

Last week, I interviewed a woman who works in a casino. She works on her feet for 10 hours from 6pm to 4am, gets home, grabs a few hours sleep, then gets up to take her daughter to school. People at the casino often suffer from relationship breakdowns because of the hours, she says.

The work can be gruelling too. “It’s really mentally hard work sometimes, the hours are not helping us, sometimes [customers] come in drunk at 3am and you are so tired, and they are just swearing at you, so drunk you can’t handle them on the table but you have to do it because it’s your job.”

Her employer used to do things to make the job easier to cope with, but they have all been stripped away. The free warm dinner is gone, as is the break that was long enough to eat it. The taxi home at 4am is gone. The Christmas bonus is gone. The night premium has gone. “Lately it’s very often happening that people are leaving because they are depressed,” she told me.

Plenty of countries have experienced similar trends in the quality of work in certain sectors, so why might the UK be struggling more than most?

Perhaps because the countervailing mechanisms that could protect workers from these trends — the “protective shield”, as Jennifer Dixon of the Health Foundation puts it — are particularly weak in Britain. The country is bad at enforcing its own labour laws, as the P&O debacle showed this year when the company sacked hundreds of sailors without any consultation in what lawyers call an “efficient breach” of employment law. Trade union membership has declined sharply in the private sector. The Health and Safety Executive’s budget has been cut.

None of this is to say that work is entirely to blame for the nation’s worsening health. There are plenty of other possible causes, from processed foods to rising loneliness and social media, not to mention the pandemic itself and the strain on the NHS.

But I don’t think any discussion of the country’s health is complete without a clear-eyed look at the reality of life in the UK labour market for those who don’t have decent jobs. Good quality work is beneficial for health. But if we just try to patch people up and push them back into jobs that were making them sick, we won’t get anywhere at all.