In pride of place in the living room of

Paulo Coelho's apartment in Geneva is a fan's portrait of the author. A pointillist work, the huge image consists of the colour-coded coffee capsules George Clooney endorses. The background is composed of ristretto capsules (black), while Coelho's eyes seem to have been picked out in decaffeinato intenso (claret). Perhaps sadly, the artist has not used the new linizio lungo (apricot) capsule to perk up the colour scheme.

This is not the strangest gift he has received,

Coelho says. "I'm in my apartment in Rio in 2000 and the doorbell rings and there's a beautiful woman, very tall, very sexy, green eyes. She was carrying a small tree. I said: 'What is this?' She said: 'Don't speak Portuguese.' She said: 'I came from Slovenia because I want to plant this tree here and I want to have a son with you.'" Long story short – Coelho put her on a flight home and saw her only once more, with a boyfriend in Slovenia. And the tree? That's not important now, he laughs.

For the next hour and a half he laughs a lot. A genial funster has today replaced the solemn preacher-novelist damned by

one critic for writing "something David Hasselhoff might spout after a particularly taxing Baywatch rescue".

This incarnation may not be what has made the 65-year-old Brazilian an international bestselling author with 9.8 million Facebook fans, 6.3 million

Twitter followers, and a fanbase embracing readers in the Islamic republic of Iran and the socialist republic of Cuba. Personally speaking, Coelho in the flesh is more appealing than Coelho the writer.

"Do you want to see my bow?" he asks at one point. Coelho is a keen archer. He has seen

The Hunger Games and can confirm that Jennifer Lawrence's archery technique is authentic. "The only thing that relaxes me is archery. That's why I have to have apartments with gardens."

His other favourite activity is walking around Geneva. "I walk every day and I look at the mountains and the fields and the small city and I say: 'Oh my God, what a blessing.' Then you realise it's important to put it in a context beyond this woman, this man, this city, this country, this universe. It goes beyond everything. It goes to the core of our reason for being here." What if there is no reason for being here and – there's no easy way to put this – nice walks around Geneva are as good as it gets? "It's still a blessing." Good comeback.

Back to the coffee portrait. For Coelho, it demonstrates one of the cardinal virtues he extols in his new book,

Manuscript Found in Accra – elegance. Why is elegance important? "I don't know what I wrote in the book, but elegance goes to the basics." He points to his portrait. "This is very elegant because if you take an isolated Nespresso capsule, it would mean nothing but with three or four you can create anything. So for me elegance is this." Nespresso PR people who are liking the way this piece is going so far may want to excise the next sentence from their press pack: "I don't drink Nespresso by the way."

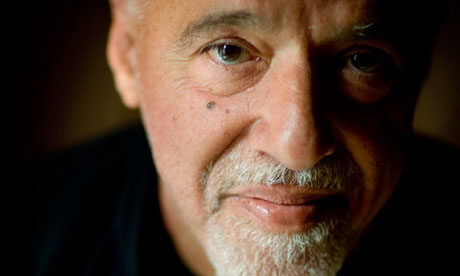

Coelho's colour scheme is as minimalist as his portrait. Today he looks like a Brazilian

Sweet Gene Vincent: white face, black coat, white beard, black trousers, white shirt over black T-shirt, white wisps of hair, trailing behind him as he struts through the apartment in Cuban heels sipping black coffee. He has a butterfly tattoo on his left wrist.

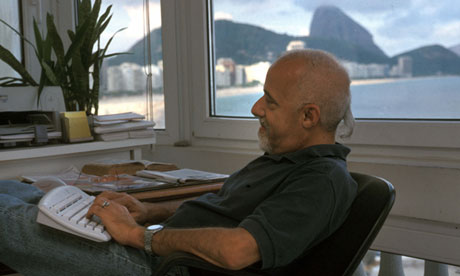

Paulo Coelho in his office in 1995. Photograph: Roger-Viollet

Paulo Coelho in his office in 1995. Photograph: Roger-Viollet

The other virtues set out in his new book are boldness, love and friendship. A pedant might note that elsewhere in his writings, Coelho has argued that friendship is a form of love so should not be considered a distinct virtue. Also courage rather than boldness is the virtue you need if you are to realise the the message,

expressed in his 1988 novel, The Alchemist, that wherever your heart is you will find treasure. But nobody, least of all Coelho, would suggest the oeuvre of the writer, who has sold 145m books worldwide and been translated into 74 languages, is devoid of contradictions. "If I have to summarise this book in one sentence, which would be very difficult," he says, "it is this: accept your contradictions. Learn how to live with them. Because they aren't curses – they are blessings."

The Jesus of the gospels was, Coelho argues, similarly contradictory. "Jesus lived a life that was full of joy and contradictions and fights, you know?" says Coelho, his brown eyes sparkling. "If they were to paint a picture of Jesus without contradictions, the gospels would be fake, but the contradictions are a sign of authenticity. So Jesus says: 'Turn the other face,' and then he can get a whip and go woosh! The same man who says: 'Respect your father and mother' says: 'Who is my mother?' So this is what I love – he is a man for all seasons."

Like Jesus, he's not expressing a coherent doctrine that can be applied to life like a blueprint? "You can't have a blueprint for life. This is the problem if you're religious today. I am Catholic myself, I go to the mass. But I see you can have faith and be a coward. Sometimes people renounce living in the name of a faith which is a killer faith. I like this expression – killer faith."

Coelho proposes a faith based on joy. "The more in harmony with yourself you are, the more joyful you are, and the more faithful you are. Faith is not to disconnect you from reality, it connects you to reality."

In this view, he thinks he has Jesus on his side. "They [those who model their sacrifice on Christ's] remember three days in the life of Jesus when he was crucified. They forget that Jesus was politically incorrect from beginning to end. He was a bon vivant – travelling, drinking, socialising all his life. His first miracle was not to heal a poor blind person. It was changing water into wine and not wine into water."

Paulo Coelho insists he has led a joyful, fulfilling life. It could easily have been otherwise. Born in Rio de Janeiro in 1947, he longed from a young age to become a writer, an ambition his parents frowned upon so much that they sent him, aged 17, to an asylum. "My parents thought I was psychotic. Like now, I read a lot and I didn't socialise. They wanted to help me."

He was eventually released in 1967 and enrolled in law school – one of several attempts to become, as he puts it disdainfully, "normal". Later he dropped out, became a hippy and made a fortune writing lyrics for

Raul Seixas, the Brazilian rock star. Brazil's ruling militia took exception to his lyrics (some of which were influenced by the satanist Aleister Crowley). As a result, he was repeatedly arrested for subversion and eventually tortured with electric shocks to his genitals. These experiences, incidentally, account for his scorn for the idea that Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, who was photographed with Coelho's books on his shelves, might have learned anything from the Brazilian's thought: "I think he had never read my books. It was PR. I wonder if he knew the story of the author he would have been proud of having this book on his shelves. I was part of these dreadful years in South America."

Why, given his history, didn't he choose the path of renunciation? "But I did! After the asylum and torture, I said: 'I am tired. Enough. Let me behave like a normal person. Let me be the person who my parents wanted me to be – or society or whatever.' So back in 1975 I married someone in church, got a job. I was normal for seven years. I could not stand to be normal. Then I divorced and married another person who is now my wife [the artist

Christina Oiticica] and I said: 'Let's travel and try to find the meaning of life.' I had money because I had been a very successful songwriter, so I had five apartments in Brazil. I sold everything and I started travelling."

His epiphany came in 1986 when he walked the 500-mile road to the Galician pilgrimage site

Santiago de Compostela. He described his spiritual awakening there in one of his earliest novels,

The Pilgrimage. "Then I said: 'It's now or never.' I stopped everything and said: 'Now I am going to fulfil my dream. I may be defeated but I will not fail.'"

This distinction between defeats and failure is central to Coelho's new book. The former are incidental, chastening wounds risked by those who listen to their heart, the latter a lifelong abnegation of the responsibility to follow your dream. Or as the narrator of Manuscript Found in Accra puts it: "Take pride in your scars. Scars are medals branded on the flesh and your enemies will be frightened by them because they are proof of your long experience of battle." That advice is borne of his life experiences? "Absolutely. I am proud of my scars and they taught me to live better and not to be afraid of living."

He looks at me sharply: "They taught me also to be a cold-blooded killer." Beg your pardon? "When I see people trying to manipulate me, I kill. No regrets, no hatred, just an act of – " He makes a throat-cutting gesture. He's not the fluffy bunny his writings might indicate him to be? "Ha! No! I can be very tough. If people think you're naive, they discover in the next second that they don't have heads. So love your enemy, but keep your blacklist updated."

Coelho clearly thinks highly of his readers and online fans. Indeed, Manuscript Found in Accra could be considered the ultimate tribute to them – the collaboration of sage and his online disciples. Share your fears, Coelho tweeted his followers, that I might offer hope and comfort. The resultant book consists of Coelho's meditations on such themes as courage, solitude, loyalty, anxiety, loss, sex and victimhood suggested by followers. Manuscript Found in Accra might function as an aphoristic grab bag of his principal thoughts. The treacly narratives of such novels as The Alchemist and Eleven Minutes have been excised but the cliches remain. He actually does write stuff like this: "It is better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all" and "Don't give up. Remember it's always the last key on the ring that opens the door." Those of you who may so far have resisted the endorsements of Madonna, Julia Roberts or Bill Clinton may now be tempted to read him if only to test the proposition that Paulo Coelho exists to make Alain de Botton look deep.

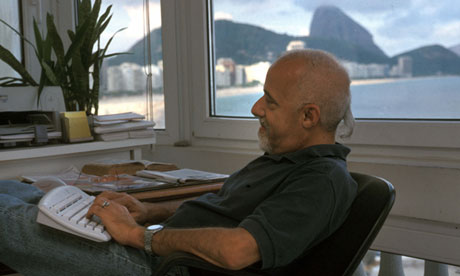

Paulo Coelho and his wife Christina at home in Rio in 1996. Photograph: Robert Van Der Hilst/Gamma/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Paulo Coelho and his wife Christina at home in Rio in 1996. Photograph: Robert Van Der Hilst/Gamma/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Coelho lightly fictionalises this collection of putative aphorisms: the conceit is that we're reading a manuscript lost for 700 years, based on the talk a mysterious scholar called the Copt gave to the citizens of Jerusalem on the eve of its invasion by French crusaders. "The great wisdom of life," the Copt says toward the end of the book, "is that we can be masters of the things that try to enslave us."

How? Coelho says: "By taking responsibility. Today people aren't encouraged to take responsibility. It's easy to obey because you can blame a wrong decision on the person who told you to do this or do that. From the moment you accept that you're the master of your destiny you have to accept responsibility for every single action of yours. So why bother to follow my dreams? Then I can avoid being a failure – which is not true of course: you are a failure from the moment you don't allow yourself to be defeated."

Coelho by contrast snatched victory from the jaws of his several defeats. "Am I hyper rich? Yes. Do I want to prove this? No. Go back to your essence – don't play this consumerism game. This is nonsense. At the end of the day, the day that you die, the last minute, you have to answer this question: Did I really enjoy my life?"

How will he answer this question? "On 30 November 2011 I did," he says enigmatically. In that month, he was prompted to go for a scan by his agent Mônica Antunes, whose father had recently died of a heart attack. "She was worried that both her husband and I were smokers. I said: 'No way, Jose. Come on. I walk every day. I have a very healthy life. I don't smoke much – six cigarettes a day.'" But the day after his wife's 60th birthday he visited the cardiologist for tests. "He said: 'You're going to die.' I said: 'I don't believe you.' He said: 'You're going to die in 30 days. This part of your heart does not respond any more to electric impulses so probably it is blocked.'

"I was shocked of course. But I had time to answer this question that you just asked me. I remember I was in my bedroom and I said: 'If I die tomorrow, I would die very happy. First, I did everything I wanted to do in this life – sex, drugs, rock'n'roll. You name it I did it. Orgies and whatever." Orgies? "Oh yes. Orgies. Ha ha ha!

"Second, I had my share of losing but I did not quit. Third, I followed my road, my bliss, my personal life journey and I chose to be a writer. And I succeeded, which is more difficult, you know?

"Fourth, I've been married for 33 years to the love of my life. So what else can I ask? I will die with a smile on my face, with no fear, and I believe in God. So no problem if I die tomorrow. That is what I thought."

Paulo Coelho, you will have noticed, did not die when his doctor said he would. "But I pray that when I die I will die with the same state of mind I had on the 30th of November 2011."

How would he counsel his followers to die contented? "I can't tell them. I only know that the most important gift that you have is courage – be courageous." He lights a cigarette and smokes it in seeming defiance of what he calls the Unwanted Visitor, death.

In the January of every odd year since 1988, he has tried to find a white feather. Only if he succeeds does he write a book. Unfortunately for some of his critics, he found one earlier this year and so plans to write another book. It won't take long. "I write a book in 15 days. Then I go to social communities – I love social communities."

He means Twitter and Facebook. Why? "Twitter I think is an art. Because if you're connected to people you learn how to summarise. I used to do that when I used to write lyrics. It was always the tendency of my life to be clear without being superficial." He's not superficial? "No. Each sentence is dense, poetic."

Coelho signs a copy of his book for me: "Avoid those who say: 'I will go no further.' Love, Paulo Coelho."

As I walk from his apartment into a city of writers greater than Coelho (Rousseau was born and Borges died here), I wish, though not wanting to be ungrateful, he'd chosen a better quote from his book. For example: "Fate is never unfair to anyone. We are all free to hate or love what we do." That seems to me Coelho at his best, going beyond upbeat banalities and challenging those who make victimhood their identity.

At least he didn't write: "Cross me and you die." Though clearly he could have done.