'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Sunday, 28 April 2024

Friday, 12 January 2024

What is the world's loveliest language?

From The Economist

Linguists tend to say that all languages are valuable, expressive and complex. They usually attribute negative attitudes to prejudice and politics. That is probably why no one has carefully studied the touchy question of which ones are seen as beautiful or ugly.

That is until three scholars—Andrey Anikin, Nikolay Aseyev and Niklas Erben Johansson—published their study of 228 languages last year*. They hit upon the idea of using an online film about the life of Jesus, which its promoters have recorded in hundreds of languages. Crucially, most recordings had at least five different speakers, as the film has both exposition and dialogue. The team recruited 820 people from three different language groups—Chinese, English and Semitic (Arabic, Hebrew and Maltese speakers)—to listen to clips and rate the languages’ attractiveness.

What they found was that nearly all the 228 languages were rated strikingly similarly—when certain factors were controlled for (of which more below). On a scale of 1 to 100, all fell between 37 and 43, and most in a bulge between 39 and 42 (see chart 1). The highest-rated? Despite the supposed allure (at least among Anglophones) of French and Italian, it was Tok Pisin, an English creole spoken in Papua New Guinea. The lowest? Chechen. The three language groups broadly coincided in their preferences. But the differences between the best and worst-rated languages were so slight—and the variation among individual raters so great—that no one should be tempted to crown Tok Pisin the world’s prettiest language with any authority.

A few factors did make the raters say they quite liked the languages they heard. But those seem unrelated to intrinsic qualities. First, being familiar with a language—or even thinking they were familiar with it—made raters give a language a 12% prettiness boost on average. And there seemed to be some regional prejudices. If a rater said that a language was familiar, he or she was asked to say what region it came from. Chinese raters, for example, clearly preferred languages they thought to be from the Americas or Europe, and rated those they thought from sub-Saharan Africa lower. (When raters said they were unfamiliar with the languages, such preferences disappeared.)

The other extrinsic factors that influenced ratings were a strong preference for female voices and a weaker preference for deeper and breathier ones (see chart 2). But try as they might, the investigators could not find an inherent phonetic feature—such as the presence of nasal vowels (as in French bon vin blanc) or fricative consonants (like the sh and zh sounds common in Polish)—that was consistently rated as beautiful. Only a slight dislike for tonal languages was statistically significant. Tonal languages are those that use pitch to distinguish otherwise homophonous words. Even Chinese subjects slightly disliked such languages, though Chinese itself is tonal.

Dr Johansson highlights some unanswered questions. His team had no information about which sounds tend to appear together (English strings along consonants—as in “strings”—in a way that many other languages do not.) Such a feature was beyond their ability to measure. So was prosody—roughly, the rhythm of a language. And with just five speakers per language, the presence of a couple of attractive or unattractive individual speakers could easily move a language’s rating this way or that.

Finally, the audio materials were scripted. This was a good thing in one way, because the raters heard the same part of the film (with the same meanings) in each language. But spontaneous, natural speech could make quite a different impression. Perhaps people like and dislike not the sound inventory of a language, but the way its speakers tend to speak it. If that is so, the attractiveness of a language might be better attributed to its speakers’ culture—not to the language itself.

Negative results in experiments usually do not make waves, but this one is both interesting—since it goes so strongly against people’s instincts—and cheering. The world is divided enough. As the researchers conclude, “We have emphasised the fundamental phonetic and aesthetic unity of world languages.”

Sunday, 6 March 2022

Monday, 31 May 2021

Tuesday, 2 June 2020

The G20 should be leading the world out of the coronavirus crisis – but it's gone AWOL

If coronavirus crosses all boundaries, so too must the war to vanquish it. But the G20, which calls itself the world’s premier international forum for international economic cooperation and should be at the centre of waging that war, has gone awol – absent without lending – with no plan to convene, online or otherwise, at any point in the next six months.

This is not just an abdication of responsibility; it is, potentially, a death sentence for the world’s poorest people, whose healthcare requires international aid and who the richest countries depend on to prevent a second wave of the disease hitting our shores.

On 26 March, just as the full force of the pandemic was becoming clear, the G20 promised “to use all available policy tools” to support countries in need. There would be a “swift implementation” of an emergency response, it said, and its efforts would be “amplified” over the coming weeks. As the International Monetary Fund (IMF) said at the time, emerging markets and developing nations needed at least $2.5tn (£2,000bn) in support. But with new Covid-19 cases round the world running above 100,000 a day and still to peak, the vacuum left by G20 inactivity means that allocations from the IMF and the World Bank to poorer countries will remain a fraction of what is required.

And yet the economic disruption, and the decline in hours worked across the world, is now equivalent to the loss of more than 300 million full-time jobs, according to the International Labour Organization. For the first time this century, global poverty is rising, and three decades of improving living standards are now in reverse. An additional 420 million more people will fall into extreme poverty and, according to the World Food Programme, 265 million face malnutrition. Developing economies and emerging markets have none of the fiscal room for manoeuvre that richer countries enjoy, and not surprisingly more than 100 such countries have applied to the IMF for emergency support.

The G20’s failure to meet is all the more disgraceful because the global response to Covid-19 should this month be moving from its first phase, the rescue operation, to its second, a comprehensive recovery plan – and at its heart there should be a globally coordinated stimulus with an agreed global growth plan.

To make this recovery sustainable the “green new deal” needs to go global; and to help pay for it, a coordinated blitz is required on the estimated $7.4tn hidden untaxed in offshore havens.

As a group of 200 former leaders state in today’s letter to the G20, the poorest countries need international aid within days, not weeks or months. Debt relief is the quickest way of releasing resources. Until now, sub-Saharan Africa has been spending more on debt repayments than on health. The $80bn owed by the 76 poorest nations should be waived until at least December 2021.

But poor countries also need direct cash support. The IMF should dip into its $35bn reserves, and the development banks should announce they are prepared to raise additional money.

A second trillion can be raised by issuing – as we did in the global financial crisis – new international money (known as special drawing rights), which can be converted into dollars or local currency. To their credit, European countries like the UK, France and Germany have already lent some of this money to poorer countries and, if the IMF agreed, $500bn could be issued immediately and $500bn more by 2022.

And we must declare now that any new vaccine and cure will be made freely available to all who need it – and resist US pressure by supporting the World Health Organization in its efforts to ensure the poorest nations do not lose out. This Thursday, at the pledging conference held for the global vaccine alliance in London, donor countries should contribute the $7bn needed to help make immunisation more widely available.

No country can eliminate infectious diseases unless all countries do so. And it is because we cannot deal with the health nor the economic emergency without bringing the whole world together that Donald Trump’s latest counterproposal – to parade a few favoured leaders in Washington in September – is no substitute for a G20 summit.

His event would exclude Africa, the Middle East, Latin America and most of Asia, and would represent only 2 billion of the world’s 7 billion people. Yet the lesson of history is that, at key moments of crisis, we require bold, united leadership, and to resist initiatives that will be seen as “divide and rule”.

So, it is time for the other 19 G20 members to demand an early summit, and avert what would be the greatest global social and economic policy failure of our generation.

Friday, 22 February 2019

India, the Cricket World Cup and Revenge for Pulwama, Pathankot, Mumbai…

Saturday, 11 November 2017

How colonial violence came home: the ugly truth of the first world war

Today on the Western Front,” the German sociologist Max Weber wrote in September 1917, there “stands a dross of African and Asiatic savages and all the world’s rabble of thieves and lumpens.” Weber was referring to the millions of Indian, African, Arab, Chinese and Vietnamese soldiers and labourers, who were then fighting with British and French forces in Europe, as well as in several ancillary theatres of the first world war.

Faced with manpower shortages, British imperialists had recruited up to 1.4 million Indian soldiers. France enlisted nearly 500,000 troops from its colonies in Africa and Indochina. Nearly 400,000 African Americans were also inducted into US forces. The first world war’s truly unknown soldiers are these non-white combatants.

Ho Chi Minh, who spent much of the war in Europe, denounced what he saw as the press-ganging of subordinate peoples. Before the start of the Great War, Ho wrote, they were seen as “nothing but dirty Negroes … good for no more than pulling rickshaws”. But when Europe’s slaughter machines needed “human fodder”, they were called into service. Other anti-imperialists, such as Mohandas Gandhi and WEB Du Bois, vigorously supported the war aims of their white overlords, hoping to secure dignity for their compatriots in the aftermath. But they did not realise what Weber’s remarks revealed: that Europeans had quickly come to fear and hate physical proximity to their non-white subjects – their “new-caught sullen peoples”, as Kipling called colonised Asians and Africans in his 1899 poem The White Man’s Burden.

These colonial subjects remain marginal in popular histories of the war. They also go largely uncommemorated by the hallowed rituals of Remembrance Day. The ceremonial walk to the Cenotaph at Whitehall by all major British dignitaries, the two minutes of silence broken by the Last Post, the laying of poppy wreaths and the singing of the national anthem – all of these uphold the first world war as Europe’s stupendous act of self-harm. For the past century, the war has been remembered as a great rupture in modern western civilisation, an inexplicable catastrophe that highly civilised European powers sleepwalked into after the “long peace” of the 19th century – a catastrophe whose unresolved issues provoked yet another calamitous conflict between liberal democracy and authoritarianism, in which the former finally triumphed, returning Europe to its proper equilibrium.

With more than eight million dead and more than 21 million wounded, the war was the bloodiest in European history until that second conflagration on the continent ended in 1945. War memorials in Europe’s remotest villages, as well as the cemeteries of Verdun, the Marne, Passchendaele, and the Somme enshrine a heartbreakingly extensive experience of bereavement. In many books and films, the prewar years appear as an age of prosperity and contentment in Europe, with the summer of 1913 featuring as the last golden summer.

But today, as racism and xenophobia return to the centre of western politics, it is time to remember that the background to the first world war was decades of racist imperialism whose consequences still endure. It is something that is not remembered much, if at all, on Remembrance Day.

At the time of the first world war, all western powers upheld a racial hierarchy built around a shared project of territorial expansion. In 1917, the US president, Woodrow Wilson, baldly stated his intention, “to keep the white race strong against the yellow” and to preserve “white civilisation and its domination of the planet”. Eugenicist ideas of racial selection were everywhere in the mainstream, and the anxiety expressed in papers like the Daily Mail, which worried about white women coming into contact with “natives who are worse than brutes when their passions are aroused”, was widely shared across the west. Anti-miscegenation laws existed in most US states. In the years leading up to 1914, prohibitions on sexual relations between European women and black men (though not between European men and African women) were enforced across European colonies in Africa. The presence of the “dirty Negroes” in Europe after 1914 seemed to be violating a firm taboo.

Injured Indian soldiers being cared for by the Red Cross in England in March 1915. Photograph: De Agostini Picture Library/Biblioteca Ambrosiana

Injured Indian soldiers being cared for by the Red Cross in England in March 1915. Photograph: De Agostini Picture Library/Biblioteca Ambrosiana“These savages are a terrible danger,” a joint declaration of the German national assembly warned in 1920, to “German women”. Writing Mein Kampf in the 1920s, Adolf Hitler would describe African soldiers on German soil as a Jewish conspiracy aimed to topple white people “from their cultural and political heights”. The Nazis, who were inspired by American innovations in racial hygiene, would in 1937 forcibly sterilise hundreds of children fathered by African soldiers. Fear and hatred of armed “niggers” (as Weber called them) on German soil was not confined to Germany, or the political right. The pope protested against their presence, and an editorial in the Daily Herald, a British socialist newspaper, in 1920 was titled “Black Scourge in Europe”.

This was the prevailing global racial order, built around an exclusionary notion of whiteness and buttressed by imperialism, pseudo-science and the ideology of social Darwinism. In our own time, the steady erosion of the inherited privileges of race has destabilised western identities and institutions – and it has unveiled racism as an enduringly potent political force, empowering volatile demagogues in the heart of the modern west.

Today, as white supremacists feverishly build transnational alliances, it becomes imperative to ask, as Du Bois did in 1910: “What is whiteness that one should so desire it?” As we remember the first global war, it must be remembered against the background of a project of western global domination – one that was shared by all of the war’s major antagonists. The first world war, in fact, marked the moment when the violent legacies of imperialism in Asia and Africa returned home, exploding into self-destructive carnage in Europe. And it seems ominously significant on this particular Remembrance Day: the potential for large-scale mayhem in the west today is greater than at any other time in its long peace since 1945.

When historians discuss the origins of the Great War, they usually focus on rigid alliances, military timetables, imperialist rivalries, arms races and German militarism. The war, they repeatedly tell us, was the seminal calamity of the 20th century – Europe’s original sin, which enabled even bigger eruptions of savagery such as the second world war and the Holocaust. An extensive literature on the war, literally tens of thousands of books and scholarly articles, largely dwells on the western front and the impact of the mutual butchery on Britain, France, and Germany – and significantly, on the metropolitan cores of these imperial powers rather than their peripheries. In this orthodox narrative, which is punctuated by the Russian Revolution and the Balfour declaration in 1917, the war begins with the “guns of August” in 1914, and exultantly patriotic crowds across Europe send soldiers off to a bloody stalemate in the trenches. Peace arrives with the Armistice of 11 November 1918, only to be tragically compromised by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, which sets the stage for another world war.

In one predominant but highly ideological version of European history – popularised since the cold war – the world wars, together with fascism and communism, are simply monstrous aberrations in the universal advance of liberal democracy and freedom. In many ways, however, it is the decades after 1945 – when Europe, deprived of its colonies, emerged from the ruins of two cataclysmic wars – that increasingly seem exceptional. Amid a general exhaustion with militant and collectivist ideologies in western Europe, the virtues of democracy – above all, the respect for individual liberties – seemed clear. The practical advantages of a reworked social contract, and a welfare state, were also obvious. But neither these decades of relative stability, nor the collapse of communist regimes in 1989, were a reason to assume that human rights and democracy were rooted in European soil.

Instead of remembering the first world war in a way that flatters our contemporary prejudices, we should recall what Hannah Arendt pointed out in The Origins of Totalitarianism – one of the west’s first major reckonings with Europe’s grievous 20th-century experience of wars, racism and genocide. Arendt observes that it was Europeans who initially reordered “humanity into master and slave races” during their conquest and exploitation of much of Asia, Africa and America. This debasing hierarchy of races was established because the promise of equality and liberty at home required imperial expansion abroad in order to be even partially fulfilled. We tend to forget that imperialism, with its promise of land, food and raw materials, was widely seen in the late 19th century as crucial to national progress and prosperity. Racism was – and is – more than an ugly prejudice, something to be eradicated through legal and social proscription. It involved real attempts to solve, through exclusion and degradation, the problems of establishing political order, and pacifying the disaffected, in societies roiled by rapid social and economic change.

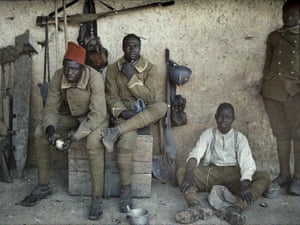

Senegalese soldiers serving in the French army on the western front in June 1917. Photograph: Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

Senegalese soldiers serving in the French army on the western front in June 1917. Photograph: Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty ImagesIn the early 20th century, the popularity of social Darwinism had created a consensus that nations should be seen similarly to biological organisms, which risked extinction or decay if they failed to expel alien bodies and achieve “living space” for their own citizens. Pseudo-scientific theories of biological difference between races posited a world in which all races were engaged in an international struggle for wealth and power. Whiteness became “the new religion”, as Du Bois witnessed, offering security amid disorienting economic and technological shifts, and a promise of power and authority over a majority of the human population.

The resurgence of these supremacist views today in the west – alongside the far more widespread stigmatisation of entire populations as culturally incompatible with white western peoples – should suggest that the first world war was not, in fact, a profound rupture with Europe’s own history. Rather it was, as Liang Qichao, China’s foremost modern intellectual, was already insisting in 1918, a “mediating passage that connects the past and the future”.

The liturgies of Remembrance Day, and evocations of the beautiful long summer of 1913, deny both the grim reality that preceded the war and the way it has persisted into the 21st century. Our complex task during the war’s centenary is to identify the ways in which that past has infiltrated our present, and how it threatens to shape the future: how the terminal weakening of white civilisation’s domination, and the assertiveness of previously sullen peoples, has released some very old tendencies and traits in the west.

Nearly a century after first world war ended, the experiences and perspectives of its non-European actors and observers remain largely obscure. Most accounts of the war uphold it as an essentially European affair: one in which the continent’s long peace is shattered by four years of carnage, and a long tradition of western rationalism is perverted.

Relatively little is known about how the war accelerated political struggles across Asia and Africa; how Arab and Turkish nationalists, Indian and Vietnamese anti-colonial activists found new opportunities in it; or how, while destroying old empires in Europe, the war turned Japan into a menacing imperialist power in Asia.

A broad account of the war that is attentive to political conflicts outside Europe can clarify the hyper-nationalism today of many Asian and African ruling elites, most conspicuously the Chinese regime, which presents itself as avengers of China’s century-long humiliation by the west.

Recent commemorations have made greater space for the non-European soldiers and battlefields of the first world war: altogether more than four million non-white men were mobilised into European and American armies, and fighting happened in places very remote from Europe – from Siberia and east Asia to the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa, and even the South Pacific islands. In Mesopotamia, Indian soldiers formed a majority of Allied manpower throughout the war. Neither Britain’s occupation of Mesopotamia nor its successful campaign in Palestine would have occurred without Indian assistance. Sikh soldiers even helped the Japanese to evict Germans from their Chinese colony of Qingdao.

Scholars have started to pay more attention to the nearly 140,000 Chinese and Vietnamese contract labourers hired by the British and French governments to maintain the war’s infrastructure, mostly digging trenches. We know more about how interwar Europe became host to a multitude of anticolonial movements; the east Asian expatriate community in Paris at one point included Zhou Enlai, later the premier of China, as well as Ho Chi Minh. Cruel mistreatment, in the form of segregation and slave labour, was the fate of many of these Asians and Africans in Europe. Deng Xiaoping, who arrived in France just after the war, later recalled “the humiliations” inflicted upon fellow Chinese by “the running dogs of capitalists”.

But in order to grasp the current homecoming of white supremacism in the west, we need an even deeper history – one that shows how whiteness became in the late 19th century the assurance of individual identity and dignity, as well as the basis of military and diplomatic alliances.

Such a history would show that the global racial order in the century preceding 1914 was one in which it was entirely natural for “uncivilised” peoples to be exterminated, terrorised, imprisoned, ostracised or radically re-engineered. Moreover, this entrenched system was not something incidental to the first world war, with no connections to the vicious way it was fought or to the brutalisation that made possible the horrors of the Holocaust. Rather, the extreme, lawless and often gratuitous violence of modern imperialism eventually boomeranged on its originators.

In this new history, Europe’s long peace is revealed as a time of unlimited wars in Asia, Africa and the Americas. These colonies emerge as the crucible where the sinister tactics of Europe’s brutal 20th-century wars – racial extermination, forced population transfers, contempt for civilian lives – were first forged. Contemporary historians of German colonialism (an expanding field of study) try to trace the Holocaust back to the mini-genocides Germans committed in their African colonies in the 1900s, where some key ideologies, such as Lebensraum, were also nurtured. But it is too easy to conclude, especially from an Anglo-American perspective, that Germany broke from the norms of civilisation to set a new standard of barbarity, strong-arming the rest of the world into an age of extremes. For there were deep continuities in the imperialist practices and racial assumptions of European and American powers.

Indeed, the mentalities of the western powers converged to a remarkable degree during the high noon of “whiteness” – what Du Bois, answering his own question about this highly desirable condition, memorably defined as “the ownership of the Earth for ever and ever”. For example, the German colonisation of south-west Africa, which was meant to solve the problem of overpopulation, was often assisted by the British, and all major western powers amicably sliced and shared the Chinese melon in the late 19th century. Any tensions that arose between those dividing the booty of Asia and Africa were defused largely peacefully, if at the expense of Asians and Africans.

Campaigners calling for the removal of a statue of British imperialist Cecil Rhodes (upper right) at Oriel College in Oxford. Photograph: Martin Godwin for the Guardian

Campaigners calling for the removal of a statue of British imperialist Cecil Rhodes (upper right) at Oriel College in Oxford. Photograph: Martin Godwin for the GuardianThis is because colonies had, by the late 19th century, come to be widely seen as indispensable relief-valves for domestic socio-economic pressures. Cecil Rhodes put the case for them with exemplary clarity in 1895 after an encounter with angry unemployed men in London’s East End. Imperialism, he declared, was a “solution for the social problem, ie in order to save the 40 million inhabitants of the United Kingdom from a bloody civil war, we colonial statesmen must acquire new lands to settle the surplus population, to provide new markets for the goods produced in the factories and mines”. In Rhodes’ view, “if you want to avoid civil war, you must become imperialists”.

Rhodes’ scramble for Africa’s gold fields helped trigger the second Boer war, during which the British, interning Afrikaner women and children, brought the term “concentration camp” into ordinary parlance. By the end of the war in 1902, it had become a “commonplace of history”, JA Hobson wrote, that “governments use national animosities, foreign wars and the glamour of empire-making in order to bemuse the popular mind and divert rising resentment against domestic abuses”.

With imperialism opening up a “panorama of vulgar pride and crude sensationalism”, ruling classes everywhere tried harder to “imperialise the nation”, as Arendt wrote. This project to “organise the nation for the looting of foreign territories and the permanent degradation of alien peoples” was quickly advanced through the newly established tabloid press. The Daily Mail, right from its inception in 1896, stoked vulgar pride in being white, British and superior to the brutish natives – just as it does today.

At the end of the war, Germany was stripped of its colonies and accused by the victorious imperial powers, entirely without irony, of ill-treating its natives in Africa. But such judgments, still made today to distinguish a “benign” British and American imperialism from the German, French, Dutch and Belgian versions, try to suppress the vigorous synergies of racist imperialism. Marlow, the narrator of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899), is clear-sighted about them: “All Europe contributed to the making of Kurtz,” he says. And to the new-fangled modes of exterminating the brutes, he might have added.

In 1920, a year after condemning Germany for its crimes against Africans, the British devised aerial bombing as routine policy in their new Iraqi possession – the forerunner to today’s decade-long bombing and drone campaigns in west and south Asia. “The Arab and Kurd now know what real bombing means,” a 1924 report by a Royal Air Force officer put it. “They now know that within 45 minutes a full-sized village … can be practically wiped out and a third of its inhabitants killed or injured.” This officer was Arthur “Bomber” Harris, who in the second world war unleashed the firestorms of Hamburg and Dresden, and whose pioneering efforts in Iraq helped German theorising in the 1930s about der totale krieg (the total war).

It is often proposed that Europeans were indifferent to or absent-minded about their remote imperial possessions, and that only a few dyed-in-the-wool imperialists like Rhodes, Kipling and Lord Curzon cared enough about them. This makes racism seem like a minor problem that was aggravated by the arrival of Asian and African immigrants in post-1945 Europe. But the frenzy of jingoism with which Europe plunged into a bloodbath in 1914 speaks of a belligerent culture of imperial domination, a macho language of racial superiority, that had come to bolster national and individual self-esteem.

Italy actually joined Britain and France on the Allied side in 1915 in a fit of popular empire-mania (and promptly plunged into fascism after its imperialist cravings went unslaked). Italian writers and journalists, as well as politicians and businessmen, had lusted after imperial power and glory since the late 19th century. Italy had fervently scrambled for Africa, only to be ignominiously routed by Ethiopia in 1896. (Mussolini would avenge that in 1935 by dousing Ethiopians with poison gas.) In 1911, it saw an opportunity to detach Libya from the Ottoman empire. Coming after previous setbacks, its assault on the country, greenlighted by both Britain and France, was vicious and loudly cheered at home. News of the Italians’ atrocities, which included the first bombing from air in history, radicalised many Muslims across Asia and Africa. But public opinion in Italy remained implacably behind the imperial gamble.

Germany’s own militarism, commonly blamed for causing Europe’s death spiral between 1914 and 1918, seems less extraordinary when we consider that from the 1880s, many Germans in politics, business and academia, and such powerful lobby groups as the Pan-German League (Max Weber was briefly a member), had exhorted their rulers to achieve the imperial status of Britain and France. Furthermore, all Germany’s military engagements from 1871 to 1914 occurred outside Europe. These included punitive expeditions in the African colonies and one ambitious foray in 1900 in China, where Germany joined seven other European powers in a retaliatory expedition against young Chinese who had rebelled against western domination of the Middle Kingdom.

Troops under German command in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania (then part of German East Africa), circa 1914. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Troops under German command in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania (then part of German East Africa), circa 1914. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesDispatching German troops to Asia, the Kaiser presented their mission as racial vengeance: “Give no pardon and take no prisoners,” he said, urging the soldiers to make sure that “no Chinese will ever again even dare to look askance at a German”. The crushing of the “Yellow Peril” (a phrase coined in the 1890s) was more or less complete by the time the Germans arrived. Nevertheless, between October 1900 and spring 1901 the Germans launched dozens of raids in the Chinese countryside that became notorious for their intense brutality.

One of the volunteers for the disciplinary force was Lt Gen Lothar von Trotha, who had made his reputation in Africa by slaughtering natives and incinerating villages. He called his policy “terrorism”, adding that it “can only help” to subdue the natives. In China, he despoiled Ming graves and presided over a few killings, but his real work lay ahead, in German South-West Africa (contemporary Namibia) where an anti-colonial uprising broke out in January 1904. In October of that year, Von Trotha ordered that members of the Herero community, including women and children, who had already been defeated militarily, were to be shot on sight and those escaping death were to be driven into the Omaheke Desert, where they would be left to die from exposure. An estimated 60,000-70,000 Herero people, out of a total of approximately 80,000, were eventually killed, and many more died in the desert from starvation. A second revolt against German rule in south-west Africa by the Nama people led to the demise, by 1908, of roughly half of their population.

Such proto-genocides became routine during the last years of European peace. Running the Congo Free State as his personal fief from 1885 to 1908, King Leopold II of Belgium reduced the local population by half, sending as many as eight million Africans to an early death. The American conquest of the Philippines between 1898 and 1902, to which Kipling dedicated The White Man’s Burden, took the lives of more than 200,000 civilians. The death toll perhaps seems less startling when one considers that 26 of the 30 US generals in the Philippines had fought in wars of annihilation against Native Americans at home. One of them, Brigadier General Jacob H Smith, explicitly stated in his order to the troops that “I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn. The more you kill and burn the better it will please me”. In a Senate hearing on the atrocities in the Philippines, General Arthur MacArthur (father of Douglas) referred to the “magnificent Aryan peoples” he belonged to and the “unity of the race” he felt compelled to uphold.

The modern history of violence shows that ostensibly staunch foes have never been reluctant to borrow murderous ideas from one another. To take only one instance, the American elite’s ruthlessness with blacks and Native Americans greatly impressed the earliest generation of German liberal imperialists, decades before Hitler also came to admire the US’s unequivocally racist policies of nationality and immigration. The Nazis sought inspiration from Jim Crow legislation in the US south, which makes Charlottesville, Virginia, a fitting recent venue for the unfurling of swastika banners and chants of “blood and soil”.

In light of this shared history of racial violence, it seems odd that we continue to portray the first world war as a battle between democracy and authoritarianism, as a seminal and unexpected calamity. The Indian writer Aurobindo Ghose was one among many anticolonial thinkers who predicted, even before the outbreak of war, that “vaunting, aggressive, dominant Europe” was already under “a sentence of death”, awaiting “annihilation” – much as Liang Qichao could see, in 1918, that the war would prove to be a bridge connecting Europe’s past of imperial violence to its future of merciless fratricide.

These shrewd assessments were not Oriental wisdom or African clairvoyance. Many subordinate peoples simply realised, well before Arendt published The Origins of Totalitarianism in 1951, that peace in the metropolitan west depended too much on outsourcing war to the colonies.

The experience of mass death and destruction, suffered by most Europeans only after 1914, was first widely known in Asia and Africa, where land and resources were forcefully usurped, economic and cultural infrastructure systematically destroyed, and entire populations eliminated with the help of up-to-date bureaucracies and technologies. Europe’s equilibrium was parasitic for too long on disequilibrium elsewhere.

In the end, Asia and Africa could not remain a safely remote venue for Europe’s wars of aggrandisement in the late 19th and 20th century. Populations in Europe eventually suffered the great violence that had long been inflicted on Asians and Africans. As Arendt warned, violence administered for the sake of power “turns into a destructive principle that will not stop until there is nothing left to violate”.

In our own time, nothing better demonstrates this ruinous logic of lawless violence, which corrupts both public and private morality, than the heavily racialised war on terror. It presumes a sub-human enemy who must be “smoked out” at home and abroad – and it has licensed the use of torture and extrajudicial execution, even against western citizens.

But, as Arendt predicted, its failures have only produced an even greater dependence on violence, a proliferation of undeclared wars and new battlefields, a relentless assault on civil rights at home – and an exacerbated psychology of domination, presently manifest in Donald Trump’s threats to trash the nuclear deal with Iran and unleash on North Korea “fire and fury like the world has never seen”.

It was always an illusion to suppose that “civilised” peoples could remain immune, at home, to the destruction of morality and law in their wars against barbarians abroad. But that illusion, long cherished by the self-styled defenders of western civilisation, has now been shattered, with racist movements ascendant in Europe and the US, often applauded by the white supremacist in the White House, who is making sure there is nothing left to violate.

The white nationalists have junked the old rhetoric of liberal internationalism, the preferred language of the western political and media establishment for decades. Instead of claiming to make the world safe for democracy, they nakedly assert the cultural unity of the white race against an existential threat posed by swarthy foreigners, whether these are citizens, immigrants, refugees, asylum-seekers or terrorists.

But the global racial order that for centuries bestowed power, identity, security and status on its beneficiaries has finally begun to break down. Not even war with China, or ethnic cleansing in the west, will restore to whiteness its ownership of the Earth for ever and ever. Regaining imperial power and glory has already proven to be a treacherous escapist fantasy – devastating the Middle East and parts of Asia and Africa while bringing terrorism back to the streets of Europe and America – not to mention ushering Britain towards Brexit.

No rousing quasi-imperialist ventures abroad can mask the chasms of class and education, or divert the masses, at home. Consequently, the social problem appears insoluble; acrimoniously polarised societies seem to verge on the civil war that Rhodes feared; and, as Brexit and Trump show, the capacity for self-harm has grown ominously.

This is also why whiteness, first turned into a religion during the economic and social uncertainty that preceded the violence of 1914, is the world’s most dangerous cult today. Racial supremacy has been historically exercised through colonialism, slavery, segregation, ghettoisation, militarised border controls and mass incarceration. It has now entered its last and most desperate phase with Trump in power.

We can no longer discount the “terrible probability” James Baldwin once described: that the winners of history, “struggling to hold on to what they have stolen from their captives, and unable to look into their mirror, will precipitate a chaos throughout the world which, if it does not bring life on this planet to an end, will bring about a racial war such as the world has never seen”. Sane thinking would require, at the very least, an examination of the history – and stubborn persistence – of racist imperialism: a reckoning that Germany alone among western powers has attempted.

Certainly the risk of not confronting our true history has never been as clear as on this Remembrance Day. If we continue to evade it, historians a century from now may once again wonder why the west sleepwalked, after a long peace, into its biggest calamity yet.

Friday, 25 November 2016

Don’t fall for the new hopelessness. We still have the power to bring change

A friend posts a picture of a baby. A beautiful baby. A child is brought into the world, this world, and I like it on Facebook because I like it in real life. If anything can be an unreservedly good thing it is a baby. But no ... someone else says to me, while airily discussing how terrible everything is: “I don’t know why anyone would have a child now.” As though any child was ever born of reason. I wonder at their mental state, but soon read that a war between the superpowers is likely. The doom and gloom begins to get to me. There is no sealant against the dread, the constant drip of the talk of end times.

I stay up into the small hours watching the footage of triumphant white nationalists sieg-heiling with excited hesitancy. My dreams are contaminated – at the edge of them, Trump roams the Black Lodge from Twin Peaks. But then I wake up and think: “Enough.” Enough of this competitive hopelessness.

Loss is loss. Our side has taken some heavy hits, the bad guys are in charge. Some take solace in the fact that the bad guys don’t know what they are doing: Farage, Trump, Johnson, Ukip donor Arron Banks, wear their ignorance as a badge of pride. One of the “liberal” values that has been overturned is apparently basic respect for knowledge. Wilful ignorance and inadequacy is now lauded as authenticity.

However, the biggest casualty for my generation is the idea that progress is linear. Things really would get better and better, we said; the world would somehow by itself become more open, equal, tolerant, as though everything would evolve in our own self-image. Long before Brexit or the US election, it was clear that this was not the case. I have often written about the way younger generations have had more and more stripped away from them: access to education, jobs and housing. Things have not been getting better and they know that inequality has solidified. Materially, they are suffering, but culturally and demographically the resistance to authoritarian populism, or whatever we want to call this movement of men old before their time, will come from the young. It will come also from the many for whom racism or sexism in society is nothing new.

Resistance can’t come personally or politically from the abject pessimism that prevails now. Of course, anger, despair, denial are all stages of grief, and the joys of nihilism are infinite. I am relieved that we are all going to die in a solar flare, anyway, but until then pessimism replayed as easy cynicism and inertia is not going to get us anywhere. The relentless wallowing in every detail of Trump or Farage’s infinite idiocy is drowning, not waving. The oft-repeated idea that history is a loop and that this is a replay of the1930s induces nothing but terror. Nothing is a foregone conclusion. That is why we learn history.

I am not asking for false optimism here, but a way to exist in the world that does not lead to feelings of absolute powerlessness. A mass retreat into the internal, small sphere of the domestic, the redecoration of one’s own safe space, is understandable, but so much of what has happened has been just this abandonment of any shared or civic space. It is absolutely to the advantage of these far-right scaremongers that we stay in our little boxes, fearing “the streets”, fearing difference, seeing danger everywhere.

Thinking for ourselves is, to use a bad word, empowering. It also demands that we give up some of the ridiculous binaries of the left. The choice between class politics and identity politics is a false one. All politics is identity politics. It is clear that economic and cultural marginalisation intertwine and that they often produce a rejection of basic modernity. Economic anxiety manifests in a longing for a time when everything was in its place and certain. But the energy of youth disrupts this immediately, as many young people are born into a modernity that does not accept that everything is fixed, whether that is sexuality or a job for life. Telling them: “We are all doomed” says something about the passivity of my generation, not theirs.

The historian and activist Howard Zinn said in his autobiography, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train: “Pessimism becomes a self-fulfilling prophesy: it reproduces by crippling our willingness to act.”

Indeed. Campaigning for reproductive rights isn’t something that suddenly has to be done because of Trump. It always has to be done. LGBT people did not “win”. The great fault line of race has been exposed, but it was never just theoretical. The idea that any of these struggles were over could be maintained only if you were not involved in them.

After the election, Obama told his daughters to carry on: “You don’t get into a foetal position about it. You don’t start worrying about apocalypse. You say: ‘OK, where are the places where I can push to keep it moving forward.’”

Where can you push to keep it moving forward? Locally? Globally? Get out of that foetal position. Look at some cats online if it helps. We render those in power even more powerful if we act as though everything is a done deal. Take back control.

Thursday, 11 August 2016

How the World Bank’s biggest critic became its president

In a shanty town perched in the hilly outskirts of Lima, Peru, people were dying. It was 1994, and thousands of squatters – many of them rural migrants who had fled their country’s Maoist guerrilla insurgency – were crammed into unventilated hovels, living without basic sanitation. They faced outbreaks of cholera and other infectious diseases, but a government austerity program, which had slashed subsidised health care, forced many to forgo medical treatment they couldn’t afford. When food ran short, they formed ad hoc collectives to stave off starvation. A Catholic priest ministering to a parish in the slum went looking for help, and he found it in Jim Yong Kim, an idealistic Korean-American physician and anthropologist.

In his mid-30s and a recent graduate of Harvard Medical School, Kim had helped found Partners in Health, a non-profit organisation whose mission was to bring modern medicine to the world’s poor. The priest had been involved with the group in Boston, its home base, before serving in Peru, and he asked Kim to help him set up a clinic to aid his flock. No sooner had Kim arrived in Lima, however, than the priest contracted a drug-resistant form of tuberculosis and died.

Kim was devastated, and he thought he knew what to blame: the World Bank. Like many debt-ridden nations, Peru was going through “structural adjustment”, a period of lender-mandated inflation controls, privatisations and government cutbacks. President Alberto Fujimori had enacted strict policies, known collectively as “Fujishock”, that made him a darling of neoliberal economists. But Kim saw calamitous trickledown effects, including the tuberculosis epidemic that had claimed his friend and threatened to spread through the parish.

So Kim helped organise a conference in Lima that was staged like a teach-in. Hundreds of shanty town residents met development experts and vented their anger with the World Bank. “We talked about the privatisation of everything: profits and also suffering,” Kim recalls. “The argument we were trying to make is that investment in human beings should not be cast aside in the name of GDP growth.” Over the next half-decade, he would become a vociferous critic of the World Bank, even calling for its abolition. In a 2000 book, Dying for Growth, he was lead author of an essay attacking the “capriciousness” of international development policies. “The penalties for failure,” he concluded, “have been borne by the poor, the infirm and the vulnerable in poor countries that accepted the experts’ designs.”

Kim often tells this story today, with an air of playful irony, when he introduces himself – as the president of the World Bank. “I was actually out protesting and trying to shut down the World Bank,” Kim said one March afternoon, addressing a conference in Maryland’s National Harbor complex. “I’m very glad we lost that argument.”

The line always gets a laugh, but Kim uses it to illustrate a broader story of evolution. As he dispenses billions of development dollars and tees off at golf outings with Barack Obama – the US president has confessed jealousy of his impressive five handicap – Kim is a long way from Peru. The institution he leads has changed too. Structural adjustment, for one, has been phased out, and Kim says the bank can be a force for good. Yet he believes it is only just awakening to its potential – and at a precarious moment.

Last year, the percentage of people living in extreme poverty dropped below 10% for the first time. That’s great news for the world, but it leaves the World Bank somewhat adrift. Many former dependents, such as India, have outgrown their reliance on financing. Others, namely China, have become lenders in their own right. “What is the relevance of the World Bank?” Kim asked me in a recent interview. “I think that is an entirely legitimate question.”

Kim believes he has the existential answers. During his four years at the bank’s monumental headquarters on H Street in Washington, he has reorganised the 15,000-strong workforce to reflect a shift from managing country portfolios to tackling regional and global crises. He has redirected large portions of the bank’s resources (it issued more than $61bn in loans and other forms of funding last year) toward goals that fall outside its traditional mandate of encouraging growth by financing infrastructure projects – stemming climate change, stopping Ebola, addressing the conditions driving the Syrian exodus.

Yet many bank employees see Kim’s ambitions as presumptuous, even reckless, and changes undertaken to revitalise a sluggish bureaucracy have shaken it. There have been protests and purges, and critics say Kim’s habit of enunciating grandiose aspirations comes with a tendency toward autocracy. The former bank foe now stands accused of being an invasive agent, inflicting his own form of shock therapy on his staff. “The wrong changes have been done badly,” says Lant Pritchett, a former World Bank economist.

Pritchett argues that, beyond issues of personality and style, Kim’s presidency has exposed a deep ideological rift between national development, which emphasises institution-building and growth, and what Pritchett terms “humane” development, or alleviating immediate suffering. Kim, however, sees no sharp distinction: he contends that humane development is national development – and if the bank persists in believing otherwise, it could be doomed to obsolescence.

Kim likes to say that as a doctor with experience of treating the poor, his humanitarian outlook is his strongest qualification for his job – an opinion that probably vexes critics who point out that he knew little about lending before arriving at the bank. “Finance and macroeconomics are complicated, but you can actually learn them,” he says. “The hardest thing to learn is mud-between-your-toes, on-the-ground development work. You can’t learn that quickly. You can’t learn that through trips where you’re treated like a head of state. You have to have kind of done that before.”

Kim talks fast and he walks fast. Following him – a lithe, balding 56-year-old surrounded by a deferential, suited entourage – you can easily imagine him in a white coat as a physician making his rounds. He has a doctor’s diagnostic mindset too; he talks about ascertaining “the problem”, or what public-health experts call the “cause of the causes”. He thinks of poverty as an ailment and is trying to devise a “science of delivery”. It’s a philosophy built on a life-long interest in the intersection of science and humanities. Born in Seoul in 1959 to parents displaced by the Korean war, Kim emigrated to the US with his family when he was a child, eventually ending up in Muscatine, Iowa. His was one of two Asian families in the small town. His mother was an expert in Confucian philosophy, his father a dentist. Kim excelled at his studies while playing quarterback in high school. He attended Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, where he studied human biology. His father wanted him to be a doctor, but he gravitated toward anthropology. Because Harvard let him pursue a medical degree and a PhD simultaneously, he landed there. Kim struck up a friendship with Paul Farmer, a fellow student, over shared interests in health and justice. In 1987, they formed Partners in Health.

The two came of age when the World Bank’s influence was arguably at its most powerful and controversial. Conceived along with the International Monetary Fund at the 1944 Bretton Woods conference, the bank was meant to rebuild Europe. However, it found its central mission as a source of startup capital for states emerging from the demise of colonial empires. The bank could borrow money cheaply in the global markets, thanks to the creditworthiness of its shareholders (the largest being the US government), then use that money to finance the prerequisites for economic growth – things such as roads, schools, hospitals and power plants. Structural adjustment came about in response to a series of debt crises that culminated in the 1980s. The Bretton Woods institutions agreed to bail out indebted developing states if they tightened their belts and submitted to painful fiscal reforms.

To Kim and Farmer, the moral flaw in the bank’s approach was that it imposed mandates with little concern for how cutting budgets might affect people’s health. They thought that “the problem” in global health was economic inequality, and in Haiti Partners in Health pioneered a grassroots methodology to tackle it: improve the lives of communities by training locals to provide medical care (thus creating jobs) and by expanding access to food, sanitation and other basic necessities. Though hardly insurgents – they were based at Harvard, after all – the friends passionately argued that policy discussions in Geneva and Washington needed to be informed by ground truths, delivered by the people living them.

Farmer’s impressive work ethic and pious demeanour made him famous – and the subject of Tracy Kidder’s acclaimed book Mountains Beyond Mountains – but Kim was the partner with systemic ambitions. “For Paul, the question is, ‘What does it take to solve the problem of giving the best care in the world to my patients?’” Kim says. “But he doesn’t spend all his time thinking about, ‘So how do you take that to scale in 188 countries?’” (Both men, who remain close friends, have wonMacArthur Foundation “genius grants” for their work.)

Kim’s desire to shape policy landed him at the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2003, overseeing its HIV/Aids work. The job required him to relocate to Geneva with his wife – a paediatrician he had met at Harvard – and a son who was just a toddler. (They now have two children, aged 16 and seven.) In the vigorously assertive style that would become his hallmark – going where he wants to go even if he’s not sure how to get there – Kim pledged to meet an audacious goal: treating three million people in the developing world with antiretroviral drugs by 2005, a more than sixfold increase over just two years. The strategy, in Kim’s own words, was, “Push, push, push.” The “three-by-five pledge,” as it was known, ended up being impossible to reach, and Kim publicly apologised for the failure on the BBC. But the world got there in 2007 – a direct result, Kim says, of the pledge’s impact on global-health policymaking: “You have to set a really difficult target and then have that really difficult target change the way you do your work.”

Kim left the WHO in 2006. After a stopover at Harvard, where he headed a centre for health and human rights, he was hired to be president of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. He arrived in 2009, with little university management experience but characteristically high hopes. With the global recession at its zenith, however, Kim was forced to spend much of his time focused on saving Dartmouth’s endowment.

He hardly knew the difference between hedge funds and private equity, so a venture capitalist on the college’s board would drive up from Boston periodically to give him lessons, scribbling out basic financial concepts on a whiteboard or scratch paper. His tenure soon turned stormy as he proposed slashing $100m from the school’s budget and clashed with faculty members who complained about a lack of transparency. Joe Asch, a Dartmouth alumnus who writes for a widely read blog about the university, was highly critical of Kim. “He is a man who is very concerned about optics and not so concerned about follow-through,” Asch says now. “Everyone’s sense was that he was just there to punch his ticket.” Soon enough, a surprising opportunity arose.

The way Kim tells it, the call came out of the blue one Monday in March 2012. Timothy Geithner, another Dartmouth alumnus who was then the US treasury secretary, was on the line asking about Kim’s old nemesis. “Jim,” Geithner asked, “would you consider being president of the World Bank?”

When the government contacted him, Kim confesses, he had only the foggiest notion of how development finance worked. He had seen enough in his career, however, to know that running the bank would give him resources he scarcely could have imagined during his years of aid work. Instead of agonising over every drop of water in the budgetary bathtub, he could operate a global tap. “When I really saw what it meant to be a bank with a balance sheet, with a mission to end extreme poverty,” Kim says, “it’s like, wow.” His interest was bolstered by the bank’s adoption, partly in response to 1990s-era activists, ofstringent “safeguards”, or lending rules intended to protect human rights and the environment in client states.

By custom, the World Bank had always been run by an American, nominated by the US president for a five-year term. But in 2012 there was a real international race for the post. Some emerging-market nations questioned deference to the United States, and finance experts from Nigeria and Colombia announced their candidacies. After considering political heavyweights such as Susan Rice, John Kerry and Hillary Clinton – who were all more interested in other jobs – Obama decided he needed an American he could present as an outsider to replace the outgoing president, Robert Zoellick, a colourless former Goldman Sachs banker and Republican trade negotiator. Clinton suggested Kim and “championed Jim as a candidate”, says Farmer. (Partners in Health works with the Clinton Foundation.)

Embedded within the dispute over superpower prerogatives was a larger anxiety about what role the World Bank should play in the 21st century. Extreme poverty had dropped from 37% in 1990 to just under 13% in 2012, so fewer countries needed the bank’s help. With interest rates at record lows, the states that needed aid had more options for borrowing cheap capital, often without paternalistic ethical dictates. New competitors, such as investment banks, were concerned mainly with profits, not safeguards. As a result, whereas the World Bank had once enjoyed a virtual monopoly on the development-finance market, by 2012 its lending represented only about 5% of aggregate private-capital flows to the developing world, according to Martin Ravallion, a Georgetown University economist. And while the bank possessed a wealth of data, technical expertise and analytical capabilities, it was hampered by red tape. One top executive kept a chart in her office illustrating the loan process, which looked like a tangle of spaghetti.

At Kim’s White House interview, Obama still needed some convincing that the global-health expert could take on the task of reinvigorating the bank. When asked what qualified him over candidates with backgrounds in finance, Kim cited Obama’s mother’s anthropology dissertation, about Indonesian artisans threatened by globalisation, to argue that there was no substitute for on-the-ground knowledge of economic policies’ impact. Two days later, Obama unveiled his pick, declaring that it was “time for a development professional to lead the world’s largest development agency”.

Kim campaigned for the job with the zeal of a convert. In an interview with the New York Times, he praised the fact that, unlike in the 1990s, “now the notion of pro-poor development is at the core of the World Bank”. He also embarked on an international “listening tour” to meet heads of state and finance ministers, gathering ideas to shape his priorities in office. Because votes on the bank’s board are apportioned according to shareholding, the US holds the greatest sway, and Obama’s candidate was easily elected. Kim took office in July 2012, with plans to eradicate extreme poverty. Farmer cites a motto carved at the entry to the World Bank headquarters – “Our dream is a world free of poverty” – that activists such as Kim once sniggered at. “Jim said, ‘Let’s change it from a dream to a plan, and then we don’t have to mock it.’”

Kim still had to win over another powerful constituency: his staff. Bank experts consider themselves an elite fraternity. Presidents and their mission statements may come and go, but the institutional culture remains largely impervious. “The bank staff,” says Jim Adams, a former senior manager, “has never fully accepted the governance.” When Robert McNamara expanded the bank’s mission in the late 1960s, doing things such as sending helicopters to spray the African black fly larvae that spread river blindness, many staffers were “deeply distressed to see the institution ‘running off in all directions’”, according to a history published in 1973. When James Wolfensohn arrived in the mid-1990s with plans to move away from structural adjustment and remake the bank like a consulting firm, employees aired their gripes in the press. “Shake-up or cock-up?” asked an Economist headline. Paul Wolfowitz, whose presidency was marred by leaks, was pushed out in 2007 after accusations of cronyism resulted in a damning internal investigation.

Recognising this fraught history, Kim went on a second listening tour: he met representatives of every bank department and obtained what he describes, in anthropologist-speak, as “almost a formal ethnography” of the place. What he lacked in economic knowledge, he made up for in charm. “Dr Kim is personable, Dr Kim is articulate, Dr Kim looks very moved by what he has to say,” says Paul Cadario, a former bank executive who is now a professor at the University of Toronto.

The initial goodwill, however, vanished when Kim announced his own structural adjustment: a top-to-bottom reorganisation of the bank. It wasn’t so much the idea of change that riled up the staff. Even before Kim took office, respected voices were calling for a shakeup. In 2012, a group of bank alumni published a report criticising an “archaic management structure”; low morale was causing staff turnover, and there was an overreliance on consultants, promotion on the basis of nationality, and a “Balkanisation of expertise”. Where Kim went awry, opponents say, was in imposing his will without first garnering political support. “One famous statement is that the World Bank is a big village,” says Cadario, now a Kim critic. “And if you live in a village, it is a really bad idea to have enemies.”

The bank had been designed around the idea that local needs, assessed by staff assigned to particular countries and regions, should dictate funding; cooperation across geographical lines required internal wrangling over resources. So Kim decided to dismantle existing networks. He brought in the management consulting firm McKinsey & Co, which recommended regrouping the staff into 14 “global practices”, each of which would focus on a policy area, such as trade, agriculture or water. Kim hired outsiders to lead some departments and pushed out several formerly powerful officials with little explanation. To symbolise that he was knocking down old walls, he had a palatial, wood-panelled space on the World Bank’s executive floor retrofitted as a Silicon Valley-style open-plan office, where he could work alongside his top staff.

Kim also announced that he would cut $400m in administrative expenses, and eliminate about 500 jobs – a necessary measure, he said, because low interest rates were cutting into the bank’s profits. Kim says he “made a very conscious decision to let anyone who wanted… air their grievances.” His opponents detected no such tolerance, however, and their criticisms turned ad hominem. Around Halloween in 2014, a satirical newsletter circulated among the staff, depicting Kim as Dr Frankenstein: “Taking random pieces from dead change management theories,” it read, “he and his band of external consultants cobble together an unholy creature resembling no development bank ever seen before.” Anonymous fliers attacking Kim also began to appear around bank headquarters.

Kim portrayed internal dissent as a petty reaction to perks such as travel per diems being cut. “There’s grumbling about parking and there’s grumbling about breakfast,” he told the Economist. Meanwhile, bank staffers whispered about imperial indulgences on Kim’s part, such as chartering a private jet. (Kim claims this is a longstanding practice among bank presidents, which he only uses when there are no other options.)

A French country officer named Fabrice Houdart emerged as a lead dissenter, broadcasting his frustrations with Kim in a blog on the World Bank’s intranet. In one post, he questioned whether “a frantic race to show savings… might lead to irreversible long-term damages to the institution.” (This being the World Bank, his sedition was often illustrated with charts and statistics.) The staff went into open rebellion after Houdart revealed that Bertrand Badré, the chief financial officer, whom Kim had hired and who was in charge of cutting budgets, had received a nearly $100,000 bonus on top of his $379,000 salary. Kim addressed a raucous town hall meeting in October 2014, where he told furious staffers, “I am just as tired of the change process as all of you are.”

A few months later, Houdart was demoted after being investigated for leaking a privileged document. The alleged disclosure was unrelated to Kim’s reorganisation – it had to do with Houdart’s human rights advocacy, for which he was well known at the bank – and Kim says the investigation began before Houdart’s denunciations of his presidency. Critics, however, portray it as retaliatory. “Fabrice has become a folk hero,” Cadario says, “because he was brave enough to say what many of the people within the bank are thinking.” (Houdart is currently disputing his demotion before an internal administrative tribunal.)

“It’s never fun when large parts of the organisation are criticising you personally,” Kim admits. Yet he maintains that his tough decisions were necessary. “In order to do a real change, you have to put jobs at risk,” he says. “And completely understandably, people hate that.”

In the heat of the staff revolt, Kim was devoting attention to a very different crisis: Ebola. In contrast with the bank’s historically cautious, analytical approach, Kim was pushing it to become more involved in emergency response. He committed $400m to confront the epidemic immediately, a quarter of which he pushed out in just nine days. He dispatched bank employees to afflicted west African countries and reproached the head of the WHO for the organisation’s lack of urgency. “Rather than being tied up in bureaucracy, or saying, ‘We don’t do those things,’ Jim is saying that if poor people’s lives are at risk… then it is our business,” says Tim Evans, whom Kim hired to run the bank’s new global practice for health.

Some bank veterans disagreed, vehemently. Nearly two years on, they still worry that in trying to save the day, Kim runs the risk of diverting the bank from its distinct mission. “Pandemic response is important – but it’s not the WHO, it’s the World Bank,” says Jean-Louis Sarbib, a former senior vice-president who now runs a nonprofit development consultancy. “I don’t think he understands the World Bank is not a very large NGO.” Referencing Kim’s work with Partners in Health, Sarbib adds, “The work of the World Bank is to create a system so that he doesn’t need to come and create a clinic in Haiti.”

In reply to this critique, Kim likes to cite a study co-written by a former World Bank economist, Larry Summers, that found that 24% of full-income growth in developing countries between 2000 and 2011 was attributable to improved public health. Put simply, Kim says, pandemics and other health deficits represent enormous threats to economic development, so they should be the World Bank’s business. The same goes for climate change, which the bank is fighting by funding a UN initiative to expand sustainable energy. As for violent conflicts, rather than waiting until the shooting has stopped and painstakingly preparing a post-conflict assessment – as the bank has done in the past – Kim wants to risk more capital in insecure zones.

“We… bought into this notion that development is something that happens after the humanitarian crisis is over,” Kim said at a recent event called the Fragility Forum, where he sat next to representatives of various aid groups and the president of the Central African Republic in the World Bank’s sun-soaked atrium. “We are no longer thinking that way.”

After the forum, amid a whirlwind day of meetings and speeches, Kim stopped at a hotel cafe with me to unwind for a few minutes. As a counterweight to his life’s demands, he practices Korean Zen-style meditation, but he also seems to blow off steam by brainstorming aloud. Goals and promises came pouring out of him like a gusher. Besides eliminating extreme poverty, which he has now promised will be done by 2030, Kim wants to raise incomes among the bottom 40% of the population in every country. He also wants to achieve universal access to banking services by 2020.

Long past our allotted interview time, Kim told me he had just one more idea: “Another huge issue that I want to bring to the table is childhood stunting.” At the Davos World Economic Forum this year, he explained, everyone was chattering about a “fourth industrial revolution”, which will centre on artificial intelligence, robotics and other technological leaps. But Kim thinks whole countries are starting out with a brainpower deficit because of childhood malnutrition. “These kids have fewer – literally fewer – neuronal connections than their non-stunted classmates,” he said. “For every inch that you’re below the average height, you lose 2% of your income.”

“This is fundamentally an economic issue,” he continued. “We need to invest in grey-matter infrastructure. Neuronal infrastructure is quite possibly going to be the most important infrastructure.”

To World Bank traditionalists, addressing nutrition is an example of the sort of mission creep that makes Kim so maddening. Despite its name and capital, the bank can’t be expected to solve all the world’s humanitarian problems. (“We are not the UN,” is an informal mantra among some staffers.) Poor countries may well prefer the bank to stick to gritty infrastructural necessities, even if Kim and his supporters have splashier goals. “The interests of its rich-country constituencies and its poor-country borrowers are diverging,” Pritchett says. “It’s like the bank has a foot on two boats. Sooner or later, it’s going to have to jump on one boat or the other, or fall in the water. So far, Jim Kim is just doing the splits.”

Kim’s defenders insist the bank hasn’t abandoned its core business. In fact, as private investment in emerging markets has contracted recently, due to instability in once-booming economies such as Brazil, countries have found more reasons to turn to the World Bank. Its primary lending unit committed $29.7bn in loans this fiscal year, nearly doubling the amount from four years earlier. “There is so much need in the world that I’m not worried we’re going to run out of projects to finance,” Kim says. He also hopes the worst of the tumult within the bank is over. A few elements of his reorganisation have been scaled back; after the new administrative structure proved unwieldy, the 14 global practices were regrouped into three divisions. Some of his more polarising hires have also left.

A five-year term, Kim says, is hardly sufficient to implement his entire agenda, and he has conveyed his desire to be reappointed in 2017. Though internal controversies have been damaging, and America’s domination of the bank remains a source of tension, the next US president (quite possibly Kim’s friend Hillary Clinton) will have a strong say in the matter. If he keeps his job, Kim wants to show that the World Bank can serve as a link between great powers and small ones, between economics and aid work – retaining its influence as old rules and boundaries are erased and new ones are scribbled into place.

Kim thinks he can succeed, so long as he keeps one foot rooted in his experiences as a doctor with mud between his toes. But he also wants to share his revelations about capital with his old comrades. “I really feel a responsibility to have this conversation with development actors who, like me 10 years ago, didn’t really understand the power of leverage,” Kim says with a guileless air.

“God,” he adds, “it is just such a powerful tool.”