In a shanty town perched in the hilly outskirts of Lima, Peru, people were dying. It was 1994, and thousands of squatters – many of them rural migrants who had fled their country’s Maoist guerrilla insurgency – were crammed into unventilated hovels, living without basic sanitation. They faced outbreaks of cholera and other infectious diseases, but a government austerity program, which had slashed subsidised health care, forced many to forgo medical treatment they couldn’t afford. When food ran short, they formed ad hoc collectives to stave off starvation. A Catholic priest ministering to a parish in the slum went looking for help, and he found it in Jim Yong Kim, an idealistic Korean-American physician and anthropologist.

In his mid-30s and a recent graduate of Harvard Medical School, Kim had helped found Partners in Health, a non-profit organisation whose mission was to bring modern medicine to the world’s poor. The priest had been involved with the group in Boston, its home base, before serving in Peru, and he asked Kim to help him set up a clinic to aid his flock. No sooner had Kim arrived in Lima, however, than the priest contracted a drug-resistant form of tuberculosis and died.

Kim was devastated, and he thought he knew what to blame: the World Bank. Like many debt-ridden nations, Peru was going through “structural adjustment”, a period of lender-mandated inflation controls, privatisations and government cutbacks. President Alberto Fujimori had enacted strict policies, known collectively as “Fujishock”, that made him a darling of neoliberal economists. But Kim saw calamitous trickledown effects, including the tuberculosis epidemic that had claimed his friend and threatened to spread through the parish.

So Kim helped organise a conference in Lima that was staged like a teach-in. Hundreds of shanty town residents met development experts and vented their anger with the World Bank. “We talked about the privatisation of everything: profits and also suffering,” Kim recalls. “The argument we were trying to make is that investment in human beings should not be cast aside in the name of GDP growth.” Over the next half-decade, he would become a vociferous critic of the World Bank, even calling for its abolition. In a 2000 book, Dying for Growth, he was lead author of an essay attacking the “capriciousness” of international development policies. “The penalties for failure,” he concluded, “have been borne by the poor, the infirm and the vulnerable in poor countries that accepted the experts’ designs.”

Kim often tells this story today, with an air of playful irony, when he introduces himself – as the president of the World Bank. “I was actually out protesting and trying to shut down the World Bank,” Kim said one March afternoon, addressing a conference in Maryland’s National Harbor complex. “I’m very glad we lost that argument.”

Medical staff treat people with Ebola in Kailahun, Sierra Leone, 2014. Photograph: Carl de Souza/AFP/Getty Images

The line always gets a laugh, but Kim uses it to illustrate a broader story of evolution. As he dispenses billions of development dollars and tees off at golf outings with Barack Obama – the US president has confessed jealousy of his impressive five handicap – Kim is a long way from Peru. The institution he leads has changed too. Structural adjustment, for one, has been phased out, and Kim says the bank can be a force for good. Yet he believes it is only just awakening to its potential – and at a precarious moment.

Last year, the percentage of people living in extreme poverty dropped below 10% for the first time. That’s great news for the world, but it leaves the World Bank somewhat adrift. Many former dependents, such as India, have outgrown their reliance on financing. Others, namely China, have become lenders in their own right. “What is the relevance of the World Bank?” Kim asked me in a recent interview. “I think that is an entirely legitimate question.”

Kim believes he has the existential answers. During his four years at the bank’s monumental headquarters on H Street in Washington, he has reorganised the 15,000-strong workforce to reflect a shift from managing country portfolios to tackling regional and global crises. He has redirected large portions of the bank’s resources (it issued more than $61bn in loans and other forms of funding last year) toward goals that fall outside its traditional mandate of encouraging growth by financing infrastructure projects – stemming climate change, stopping Ebola, addressing the conditions driving the Syrian exodus.

Yet many bank employees see Kim’s ambitions as presumptuous, even reckless, and changes undertaken to revitalise a sluggish bureaucracy have shaken it. There have been protests and purges, and critics say Kim’s habit of enunciating grandiose aspirations comes with a tendency toward autocracy. The former bank foe now stands accused of being an invasive agent, inflicting his own form of shock therapy on his staff. “The wrong changes have been done badly,” says Lant Pritchett, a former World Bank economist.

Pritchett argues that, beyond issues of personality and style, Kim’s presidency has exposed a deep ideological rift between national development, which emphasises institution-building and growth, and what Pritchett terms “humane” development, or alleviating immediate suffering. Kim, however, sees no sharp distinction: he contends that humane development is national development – and if the bank persists in believing otherwise, it could be doomed to obsolescence.

Kim likes to say that as a doctor with experience of treating the poor, his humanitarian outlook is his strongest qualification for his job – an opinion that probably vexes critics who point out that he knew little about lending before arriving at the bank. “Finance and macroeconomics are complicated, but you can actually learn them,” he says. “The hardest thing to learn is mud-between-your-toes, on-the-ground development work. You can’t learn that quickly. You can’t learn that through trips where you’re treated like a head of state. You have to have kind of done that before.”

Kim talks fast and he walks fast. Following him – a lithe, balding 56-year-old surrounded by a deferential, suited entourage – you can easily imagine him in a white coat as a physician making his rounds. He has a doctor’s diagnostic mindset too; he talks about ascertaining “the problem”, or what public-health experts call the “cause of the causes”. He thinks of poverty as an ailment and is trying to devise a “science of delivery”. It’s a philosophy built on a life-long interest in the intersection of science and humanities. Born in Seoul in 1959 to parents displaced by the Korean war, Kim emigrated to the US with his family when he was a child, eventually ending up in Muscatine, Iowa. His was one of two Asian families in the small town. His mother was an expert in Confucian philosophy, his father a dentist. Kim excelled at his studies while playing quarterback in high school. He attended Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, where he studied human biology. His father wanted him to be a doctor, but he gravitated toward anthropology. Because Harvard let him pursue a medical degree and a PhD simultaneously, he landed there. Kim struck up a friendship with Paul Farmer, a fellow student, over shared interests in health and justice. In 1987, they formed Partners in Health.

The two came of age when the World Bank’s influence was arguably at its most powerful and controversial. Conceived along with the International Monetary Fund at the 1944 Bretton Woods conference, the bank was meant to rebuild Europe. However, it found its central mission as a source of startup capital for states emerging from the demise of colonial empires. The bank could borrow money cheaply in the global markets, thanks to the creditworthiness of its shareholders (the largest being the US government), then use that money to finance the prerequisites for economic growth – things such as roads, schools, hospitals and power plants. Structural adjustment came about in response to a series of debt crises that culminated in the 1980s. The Bretton Woods institutions agreed to bail out indebted developing states if they tightened their belts and submitted to painful fiscal reforms.

The line always gets a laugh, but Kim uses it to illustrate a broader story of evolution. As he dispenses billions of development dollars and tees off at golf outings with Barack Obama – the US president has confessed jealousy of his impressive five handicap – Kim is a long way from Peru. The institution he leads has changed too. Structural adjustment, for one, has been phased out, and Kim says the bank can be a force for good. Yet he believes it is only just awakening to its potential – and at a precarious moment.

Last year, the percentage of people living in extreme poverty dropped below 10% for the first time. That’s great news for the world, but it leaves the World Bank somewhat adrift. Many former dependents, such as India, have outgrown their reliance on financing. Others, namely China, have become lenders in their own right. “What is the relevance of the World Bank?” Kim asked me in a recent interview. “I think that is an entirely legitimate question.”

Kim believes he has the existential answers. During his four years at the bank’s monumental headquarters on H Street in Washington, he has reorganised the 15,000-strong workforce to reflect a shift from managing country portfolios to tackling regional and global crises. He has redirected large portions of the bank’s resources (it issued more than $61bn in loans and other forms of funding last year) toward goals that fall outside its traditional mandate of encouraging growth by financing infrastructure projects – stemming climate change, stopping Ebola, addressing the conditions driving the Syrian exodus.

Yet many bank employees see Kim’s ambitions as presumptuous, even reckless, and changes undertaken to revitalise a sluggish bureaucracy have shaken it. There have been protests and purges, and critics say Kim’s habit of enunciating grandiose aspirations comes with a tendency toward autocracy. The former bank foe now stands accused of being an invasive agent, inflicting his own form of shock therapy on his staff. “The wrong changes have been done badly,” says Lant Pritchett, a former World Bank economist.

Pritchett argues that, beyond issues of personality and style, Kim’s presidency has exposed a deep ideological rift between national development, which emphasises institution-building and growth, and what Pritchett terms “humane” development, or alleviating immediate suffering. Kim, however, sees no sharp distinction: he contends that humane development is national development – and if the bank persists in believing otherwise, it could be doomed to obsolescence.

Kim likes to say that as a doctor with experience of treating the poor, his humanitarian outlook is his strongest qualification for his job – an opinion that probably vexes critics who point out that he knew little about lending before arriving at the bank. “Finance and macroeconomics are complicated, but you can actually learn them,” he says. “The hardest thing to learn is mud-between-your-toes, on-the-ground development work. You can’t learn that quickly. You can’t learn that through trips where you’re treated like a head of state. You have to have kind of done that before.”

Kim talks fast and he walks fast. Following him – a lithe, balding 56-year-old surrounded by a deferential, suited entourage – you can easily imagine him in a white coat as a physician making his rounds. He has a doctor’s diagnostic mindset too; he talks about ascertaining “the problem”, or what public-health experts call the “cause of the causes”. He thinks of poverty as an ailment and is trying to devise a “science of delivery”. It’s a philosophy built on a life-long interest in the intersection of science and humanities. Born in Seoul in 1959 to parents displaced by the Korean war, Kim emigrated to the US with his family when he was a child, eventually ending up in Muscatine, Iowa. His was one of two Asian families in the small town. His mother was an expert in Confucian philosophy, his father a dentist. Kim excelled at his studies while playing quarterback in high school. He attended Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, where he studied human biology. His father wanted him to be a doctor, but he gravitated toward anthropology. Because Harvard let him pursue a medical degree and a PhD simultaneously, he landed there. Kim struck up a friendship with Paul Farmer, a fellow student, over shared interests in health and justice. In 1987, they formed Partners in Health.

The two came of age when the World Bank’s influence was arguably at its most powerful and controversial. Conceived along with the International Monetary Fund at the 1944 Bretton Woods conference, the bank was meant to rebuild Europe. However, it found its central mission as a source of startup capital for states emerging from the demise of colonial empires. The bank could borrow money cheaply in the global markets, thanks to the creditworthiness of its shareholders (the largest being the US government), then use that money to finance the prerequisites for economic growth – things such as roads, schools, hospitals and power plants. Structural adjustment came about in response to a series of debt crises that culminated in the 1980s. The Bretton Woods institutions agreed to bail out indebted developing states if they tightened their belts and submitted to painful fiscal reforms.

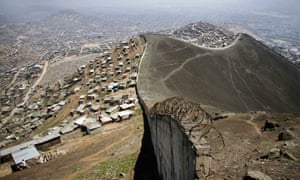

A wall dividing shanty towns and rich neighbourhoods in Lima, Peru, where Kim’s journey to the World Bank began. Photograph: Oxfam/EPA

To Kim and Farmer, the moral flaw in the bank’s approach was that it imposed mandates with little concern for how cutting budgets might affect people’s health. They thought that “the problem” in global health was economic inequality, and in Haiti Partners in Health pioneered a grassroots methodology to tackle it: improve the lives of communities by training locals to provide medical care (thus creating jobs) and by expanding access to food, sanitation and other basic necessities. Though hardly insurgents – they were based at Harvard, after all – the friends passionately argued that policy discussions in Geneva and Washington needed to be informed by ground truths, delivered by the people living them.

Farmer’s impressive work ethic and pious demeanour made him famous – and the subject of Tracy Kidder’s acclaimed book Mountains Beyond Mountains – but Kim was the partner with systemic ambitions. “For Paul, the question is, ‘What does it take to solve the problem of giving the best care in the world to my patients?’” Kim says. “But he doesn’t spend all his time thinking about, ‘So how do you take that to scale in 188 countries?’” (Both men, who remain close friends, have wonMacArthur Foundation “genius grants” for their work.)

Kim’s desire to shape policy landed him at the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2003, overseeing its HIV/Aids work. The job required him to relocate to Geneva with his wife – a paediatrician he had met at Harvard – and a son who was just a toddler. (They now have two children, aged 16 and seven.) In the vigorously assertive style that would become his hallmark – going where he wants to go even if he’s not sure how to get there – Kim pledged to meet an audacious goal: treating three million people in the developing world with antiretroviral drugs by 2005, a more than sixfold increase over just two years. The strategy, in Kim’s own words, was, “Push, push, push.” The “three-by-five pledge,” as it was known, ended up being impossible to reach, and Kim publicly apologised for the failure on the BBC. But the world got there in 2007 – a direct result, Kim says, of the pledge’s impact on global-health policymaking: “You have to set a really difficult target and then have that really difficult target change the way you do your work.”

Kim left the WHO in 2006. After a stopover at Harvard, where he headed a centre for health and human rights, he was hired to be president of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. He arrived in 2009, with little university management experience but characteristically high hopes. With the global recession at its zenith, however, Kim was forced to spend much of his time focused on saving Dartmouth’s endowment.

He hardly knew the difference between hedge funds and private equity, so a venture capitalist on the college’s board would drive up from Boston periodically to give him lessons, scribbling out basic financial concepts on a whiteboard or scratch paper. His tenure soon turned stormy as he proposed slashing $100m from the school’s budget and clashed with faculty members who complained about a lack of transparency. Joe Asch, a Dartmouth alumnus who writes for a widely read blog about the university, was highly critical of Kim. “He is a man who is very concerned about optics and not so concerned about follow-through,” Asch says now. “Everyone’s sense was that he was just there to punch his ticket.” Soon enough, a surprising opportunity arose.

The way Kim tells it, the call came out of the blue one Monday in March 2012. Timothy Geithner, another Dartmouth alumnus who was then the US treasury secretary, was on the line asking about Kim’s old nemesis. “Jim,” Geithner asked, “would you consider being president of the World Bank?”

When the government contacted him, Kim confesses, he had only the foggiest notion of how development finance worked. He had seen enough in his career, however, to know that running the bank would give him resources he scarcely could have imagined during his years of aid work. Instead of agonising over every drop of water in the budgetary bathtub, he could operate a global tap. “When I really saw what it meant to be a bank with a balance sheet, with a mission to end extreme poverty,” Kim says, “it’s like, wow.” His interest was bolstered by the bank’s adoption, partly in response to 1990s-era activists, ofstringent “safeguards”, or lending rules intended to protect human rights and the environment in client states.

To Kim and Farmer, the moral flaw in the bank’s approach was that it imposed mandates with little concern for how cutting budgets might affect people’s health. They thought that “the problem” in global health was economic inequality, and in Haiti Partners in Health pioneered a grassroots methodology to tackle it: improve the lives of communities by training locals to provide medical care (thus creating jobs) and by expanding access to food, sanitation and other basic necessities. Though hardly insurgents – they were based at Harvard, after all – the friends passionately argued that policy discussions in Geneva and Washington needed to be informed by ground truths, delivered by the people living them.

Farmer’s impressive work ethic and pious demeanour made him famous – and the subject of Tracy Kidder’s acclaimed book Mountains Beyond Mountains – but Kim was the partner with systemic ambitions. “For Paul, the question is, ‘What does it take to solve the problem of giving the best care in the world to my patients?’” Kim says. “But he doesn’t spend all his time thinking about, ‘So how do you take that to scale in 188 countries?’” (Both men, who remain close friends, have wonMacArthur Foundation “genius grants” for their work.)

Kim’s desire to shape policy landed him at the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2003, overseeing its HIV/Aids work. The job required him to relocate to Geneva with his wife – a paediatrician he had met at Harvard – and a son who was just a toddler. (They now have two children, aged 16 and seven.) In the vigorously assertive style that would become his hallmark – going where he wants to go even if he’s not sure how to get there – Kim pledged to meet an audacious goal: treating three million people in the developing world with antiretroviral drugs by 2005, a more than sixfold increase over just two years. The strategy, in Kim’s own words, was, “Push, push, push.” The “three-by-five pledge,” as it was known, ended up being impossible to reach, and Kim publicly apologised for the failure on the BBC. But the world got there in 2007 – a direct result, Kim says, of the pledge’s impact on global-health policymaking: “You have to set a really difficult target and then have that really difficult target change the way you do your work.”

Kim left the WHO in 2006. After a stopover at Harvard, where he headed a centre for health and human rights, he was hired to be president of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. He arrived in 2009, with little university management experience but characteristically high hopes. With the global recession at its zenith, however, Kim was forced to spend much of his time focused on saving Dartmouth’s endowment.

He hardly knew the difference between hedge funds and private equity, so a venture capitalist on the college’s board would drive up from Boston periodically to give him lessons, scribbling out basic financial concepts on a whiteboard or scratch paper. His tenure soon turned stormy as he proposed slashing $100m from the school’s budget and clashed with faculty members who complained about a lack of transparency. Joe Asch, a Dartmouth alumnus who writes for a widely read blog about the university, was highly critical of Kim. “He is a man who is very concerned about optics and not so concerned about follow-through,” Asch says now. “Everyone’s sense was that he was just there to punch his ticket.” Soon enough, a surprising opportunity arose.

The way Kim tells it, the call came out of the blue one Monday in March 2012. Timothy Geithner, another Dartmouth alumnus who was then the US treasury secretary, was on the line asking about Kim’s old nemesis. “Jim,” Geithner asked, “would you consider being president of the World Bank?”

When the government contacted him, Kim confesses, he had only the foggiest notion of how development finance worked. He had seen enough in his career, however, to know that running the bank would give him resources he scarcely could have imagined during his years of aid work. Instead of agonising over every drop of water in the budgetary bathtub, he could operate a global tap. “When I really saw what it meant to be a bank with a balance sheet, with a mission to end extreme poverty,” Kim says, “it’s like, wow.” His interest was bolstered by the bank’s adoption, partly in response to 1990s-era activists, ofstringent “safeguards”, or lending rules intended to protect human rights and the environment in client states.

Barack Obama nominates Kim for the presidency of the World Bank, Washington DC, 2012. Photograph: Charles Dharapak/AP

By custom, the World Bank had always been run by an American, nominated by the US president for a five-year term. But in 2012 there was a real international race for the post. Some emerging-market nations questioned deference to the United States, and finance experts from Nigeria and Colombia announced their candidacies. After considering political heavyweights such as Susan Rice, John Kerry and Hillary Clinton – who were all more interested in other jobs – Obama decided he needed an American he could present as an outsider to replace the outgoing president, Robert Zoellick, a colourless former Goldman Sachs banker and Republican trade negotiator. Clinton suggested Kim and “championed Jim as a candidate”, says Farmer. (Partners in Health works with the Clinton Foundation.)

Embedded within the dispute over superpower prerogatives was a larger anxiety about what role the World Bank should play in the 21st century. Extreme poverty had dropped from 37% in 1990 to just under 13% in 2012, so fewer countries needed the bank’s help. With interest rates at record lows, the states that needed aid had more options for borrowing cheap capital, often without paternalistic ethical dictates. New competitors, such as investment banks, were concerned mainly with profits, not safeguards. As a result, whereas the World Bank had once enjoyed a virtual monopoly on the development-finance market, by 2012 its lending represented only about 5% of aggregate private-capital flows to the developing world, according to Martin Ravallion, a Georgetown University economist. And while the bank possessed a wealth of data, technical expertise and analytical capabilities, it was hampered by red tape. One top executive kept a chart in her office illustrating the loan process, which looked like a tangle of spaghetti.

At Kim’s White House interview, Obama still needed some convincing that the global-health expert could take on the task of reinvigorating the bank. When asked what qualified him over candidates with backgrounds in finance, Kim cited Obama’s mother’s anthropology dissertation, about Indonesian artisans threatened by globalisation, to argue that there was no substitute for on-the-ground knowledge of economic policies’ impact. Two days later, Obama unveiled his pick, declaring that it was “time for a development professional to lead the world’s largest development agency”.

Kim campaigned for the job with the zeal of a convert. In an interview with the New York Times, he praised the fact that, unlike in the 1990s, “now the notion of pro-poor development is at the core of the World Bank”. He also embarked on an international “listening tour” to meet heads of state and finance ministers, gathering ideas to shape his priorities in office. Because votes on the bank’s board are apportioned according to shareholding, the US holds the greatest sway, and Obama’s candidate was easily elected. Kim took office in July 2012, with plans to eradicate extreme poverty. Farmer cites a motto carved at the entry to the World Bank headquarters – “Our dream is a world free of poverty” – that activists such as Kim once sniggered at. “Jim said, ‘Let’s change it from a dream to a plan, and then we don’t have to mock it.’”

Kim still had to win over another powerful constituency: his staff. Bank experts consider themselves an elite fraternity. Presidents and their mission statements may come and go, but the institutional culture remains largely impervious. “The bank staff,” says Jim Adams, a former senior manager, “has never fully accepted the governance.” When Robert McNamara expanded the bank’s mission in the late 1960s, doing things such as sending helicopters to spray the African black fly larvae that spread river blindness, many staffers were “deeply distressed to see the institution ‘running off in all directions’”, according to a history published in 1973. When James Wolfensohn arrived in the mid-1990s with plans to move away from structural adjustment and remake the bank like a consulting firm, employees aired their gripes in the press. “Shake-up or cock-up?” asked an Economist headline. Paul Wolfowitz, whose presidency was marred by leaks, was pushed out in 2007 after accusations of cronyism resulted in a damning internal investigation.

Recognising this fraught history, Kim went on a second listening tour: he met representatives of every bank department and obtained what he describes, in anthropologist-speak, as “almost a formal ethnography” of the place. What he lacked in economic knowledge, he made up for in charm. “Dr Kim is personable, Dr Kim is articulate, Dr Kim looks very moved by what he has to say,” says Paul Cadario, a former bank executive who is now a professor at the University of Toronto.

By custom, the World Bank had always been run by an American, nominated by the US president for a five-year term. But in 2012 there was a real international race for the post. Some emerging-market nations questioned deference to the United States, and finance experts from Nigeria and Colombia announced their candidacies. After considering political heavyweights such as Susan Rice, John Kerry and Hillary Clinton – who were all more interested in other jobs – Obama decided he needed an American he could present as an outsider to replace the outgoing president, Robert Zoellick, a colourless former Goldman Sachs banker and Republican trade negotiator. Clinton suggested Kim and “championed Jim as a candidate”, says Farmer. (Partners in Health works with the Clinton Foundation.)

Embedded within the dispute over superpower prerogatives was a larger anxiety about what role the World Bank should play in the 21st century. Extreme poverty had dropped from 37% in 1990 to just under 13% in 2012, so fewer countries needed the bank’s help. With interest rates at record lows, the states that needed aid had more options for borrowing cheap capital, often without paternalistic ethical dictates. New competitors, such as investment banks, were concerned mainly with profits, not safeguards. As a result, whereas the World Bank had once enjoyed a virtual monopoly on the development-finance market, by 2012 its lending represented only about 5% of aggregate private-capital flows to the developing world, according to Martin Ravallion, a Georgetown University economist. And while the bank possessed a wealth of data, technical expertise and analytical capabilities, it was hampered by red tape. One top executive kept a chart in her office illustrating the loan process, which looked like a tangle of spaghetti.

At Kim’s White House interview, Obama still needed some convincing that the global-health expert could take on the task of reinvigorating the bank. When asked what qualified him over candidates with backgrounds in finance, Kim cited Obama’s mother’s anthropology dissertation, about Indonesian artisans threatened by globalisation, to argue that there was no substitute for on-the-ground knowledge of economic policies’ impact. Two days later, Obama unveiled his pick, declaring that it was “time for a development professional to lead the world’s largest development agency”.

Kim campaigned for the job with the zeal of a convert. In an interview with the New York Times, he praised the fact that, unlike in the 1990s, “now the notion of pro-poor development is at the core of the World Bank”. He also embarked on an international “listening tour” to meet heads of state and finance ministers, gathering ideas to shape his priorities in office. Because votes on the bank’s board are apportioned according to shareholding, the US holds the greatest sway, and Obama’s candidate was easily elected. Kim took office in July 2012, with plans to eradicate extreme poverty. Farmer cites a motto carved at the entry to the World Bank headquarters – “Our dream is a world free of poverty” – that activists such as Kim once sniggered at. “Jim said, ‘Let’s change it from a dream to a plan, and then we don’t have to mock it.’”

Kim still had to win over another powerful constituency: his staff. Bank experts consider themselves an elite fraternity. Presidents and their mission statements may come and go, but the institutional culture remains largely impervious. “The bank staff,” says Jim Adams, a former senior manager, “has never fully accepted the governance.” When Robert McNamara expanded the bank’s mission in the late 1960s, doing things such as sending helicopters to spray the African black fly larvae that spread river blindness, many staffers were “deeply distressed to see the institution ‘running off in all directions’”, according to a history published in 1973. When James Wolfensohn arrived in the mid-1990s with plans to move away from structural adjustment and remake the bank like a consulting firm, employees aired their gripes in the press. “Shake-up or cock-up?” asked an Economist headline. Paul Wolfowitz, whose presidency was marred by leaks, was pushed out in 2007 after accusations of cronyism resulted in a damning internal investigation.

Recognising this fraught history, Kim went on a second listening tour: he met representatives of every bank department and obtained what he describes, in anthropologist-speak, as “almost a formal ethnography” of the place. What he lacked in economic knowledge, he made up for in charm. “Dr Kim is personable, Dr Kim is articulate, Dr Kim looks very moved by what he has to say,” says Paul Cadario, a former bank executive who is now a professor at the University of Toronto.

The funeral of a woman who died of Aids on the outskirts of Kigali, Rwanda. Photograph: Sean Smith for the Guardian

The initial goodwill, however, vanished when Kim announced his own structural adjustment: a top-to-bottom reorganisation of the bank. It wasn’t so much the idea of change that riled up the staff. Even before Kim took office, respected voices were calling for a shakeup. In 2012, a group of bank alumni published a report criticising an “archaic management structure”; low morale was causing staff turnover, and there was an overreliance on consultants, promotion on the basis of nationality, and a “Balkanisation of expertise”. Where Kim went awry, opponents say, was in imposing his will without first garnering political support. “One famous statement is that the World Bank is a big village,” says Cadario, now a Kim critic. “And if you live in a village, it is a really bad idea to have enemies.”

The bank had been designed around the idea that local needs, assessed by staff assigned to particular countries and regions, should dictate funding; cooperation across geographical lines required internal wrangling over resources. So Kim decided to dismantle existing networks. He brought in the management consulting firm McKinsey & Co, which recommended regrouping the staff into 14 “global practices”, each of which would focus on a policy area, such as trade, agriculture or water. Kim hired outsiders to lead some departments and pushed out several formerly powerful officials with little explanation. To symbolise that he was knocking down old walls, he had a palatial, wood-panelled space on the World Bank’s executive floor retrofitted as a Silicon Valley-style open-plan office, where he could work alongside his top staff.

Kim also announced that he would cut $400m in administrative expenses, and eliminate about 500 jobs – a necessary measure, he said, because low interest rates were cutting into the bank’s profits. Kim says he “made a very conscious decision to let anyone who wanted… air their grievances.” His opponents detected no such tolerance, however, and their criticisms turned ad hominem. Around Halloween in 2014, a satirical newsletter circulated among the staff, depicting Kim as Dr Frankenstein: “Taking random pieces from dead change management theories,” it read, “he and his band of external consultants cobble together an unholy creature resembling no development bank ever seen before.” Anonymous fliers attacking Kim also began to appear around bank headquarters.

Kim portrayed internal dissent as a petty reaction to perks such as travel per diems being cut. “There’s grumbling about parking and there’s grumbling about breakfast,” he told the Economist. Meanwhile, bank staffers whispered about imperial indulgences on Kim’s part, such as chartering a private jet. (Kim claims this is a longstanding practice among bank presidents, which he only uses when there are no other options.)

A French country officer named Fabrice Houdart emerged as a lead dissenter, broadcasting his frustrations with Kim in a blog on the World Bank’s intranet. In one post, he questioned whether “a frantic race to show savings… might lead to irreversible long-term damages to the institution.” (This being the World Bank, his sedition was often illustrated with charts and statistics.) The staff went into open rebellion after Houdart revealed that Bertrand Badré, the chief financial officer, whom Kim had hired and who was in charge of cutting budgets, had received a nearly $100,000 bonus on top of his $379,000 salary. Kim addressed a raucous town hall meeting in October 2014, where he told furious staffers, “I am just as tired of the change process as all of you are.”

A few months later, Houdart was demoted after being investigated for leaking a privileged document. The alleged disclosure was unrelated to Kim’s reorganisation – it had to do with Houdart’s human rights advocacy, for which he was well known at the bank – and Kim says the investigation began before Houdart’s denunciations of his presidency. Critics, however, portray it as retaliatory. “Fabrice has become a folk hero,” Cadario says, “because he was brave enough to say what many of the people within the bank are thinking.” (Houdart is currently disputing his demotion before an internal administrative tribunal.)

“It’s never fun when large parts of the organisation are criticising you personally,” Kim admits. Yet he maintains that his tough decisions were necessary. “In order to do a real change, you have to put jobs at risk,” he says. “And completely understandably, people hate that.”

In the heat of the staff revolt, Kim was devoting attention to a very different crisis: Ebola. In contrast with the bank’s historically cautious, analytical approach, Kim was pushing it to become more involved in emergency response. He committed $400m to confront the epidemic immediately, a quarter of which he pushed out in just nine days. He dispatched bank employees to afflicted west African countries and reproached the head of the WHO for the organisation’s lack of urgency. “Rather than being tied up in bureaucracy, or saying, ‘We don’t do those things,’ Jim is saying that if poor people’s lives are at risk… then it is our business,” says Tim Evans, whom Kim hired to run the bank’s new global practice for health.

Some bank veterans disagreed, vehemently. Nearly two years on, they still worry that in trying to save the day, Kim runs the risk of diverting the bank from its distinct mission. “Pandemic response is important – but it’s not the WHO, it’s the World Bank,” says Jean-Louis Sarbib, a former senior vice-president who now runs a nonprofit development consultancy. “I don’t think he understands the World Bank is not a very large NGO.” Referencing Kim’s work with Partners in Health, Sarbib adds, “The work of the World Bank is to create a system so that he doesn’t need to come and create a clinic in Haiti.”

In reply to this critique, Kim likes to cite a study co-written by a former World Bank economist, Larry Summers, that found that 24% of full-income growth in developing countries between 2000 and 2011 was attributable to improved public health. Put simply, Kim says, pandemics and other health deficits represent enormous threats to economic development, so they should be the World Bank’s business. The same goes for climate change, which the bank is fighting by funding a UN initiative to expand sustainable energy. As for violent conflicts, rather than waiting until the shooting has stopped and painstakingly preparing a post-conflict assessment – as the bank has done in the past – Kim wants to risk more capital in insecure zones.

“We… bought into this notion that development is something that happens after the humanitarian crisis is over,” Kim said at a recent event called the Fragility Forum, where he sat next to representatives of various aid groups and the president of the Central African Republic in the World Bank’s sun-soaked atrium. “We are no longer thinking that way.”

After the forum, amid a whirlwind day of meetings and speeches, Kim stopped at a hotel cafe with me to unwind for a few minutes. As a counterweight to his life’s demands, he practices Korean Zen-style meditation, but he also seems to blow off steam by brainstorming aloud. Goals and promises came pouring out of him like a gusher. Besides eliminating extreme poverty, which he has now promised will be done by 2030, Kim wants to raise incomes among the bottom 40% of the population in every country. He also wants to achieve universal access to banking services by 2020.

Long past our allotted interview time, Kim told me he had just one more idea: “Another huge issue that I want to bring to the table is childhood stunting.” At the Davos World Economic Forum this year, he explained, everyone was chattering about a “fourth industrial revolution”, which will centre on artificial intelligence, robotics and other technological leaps. But Kim thinks whole countries are starting out with a brainpower deficit because of childhood malnutrition. “These kids have fewer – literally fewer – neuronal connections than their non-stunted classmates,” he said. “For every inch that you’re below the average height, you lose 2% of your income.”

“This is fundamentally an economic issue,” he continued. “We need to invest in grey-matter infrastructure. Neuronal infrastructure is quite possibly going to be the most important infrastructure.”

To World Bank traditionalists, addressing nutrition is an example of the sort of mission creep that makes Kim so maddening. Despite its name and capital, the bank can’t be expected to solve all the world’s humanitarian problems. (“We are not the UN,” is an informal mantra among some staffers.) Poor countries may well prefer the bank to stick to gritty infrastructural necessities, even if Kim and his supporters have splashier goals. “The interests of its rich-country constituencies and its poor-country borrowers are diverging,” Pritchett says. “It’s like the bank has a foot on two boats. Sooner or later, it’s going to have to jump on one boat or the other, or fall in the water. So far, Jim Kim is just doing the splits.”

The initial goodwill, however, vanished when Kim announced his own structural adjustment: a top-to-bottom reorganisation of the bank. It wasn’t so much the idea of change that riled up the staff. Even before Kim took office, respected voices were calling for a shakeup. In 2012, a group of bank alumni published a report criticising an “archaic management structure”; low morale was causing staff turnover, and there was an overreliance on consultants, promotion on the basis of nationality, and a “Balkanisation of expertise”. Where Kim went awry, opponents say, was in imposing his will without first garnering political support. “One famous statement is that the World Bank is a big village,” says Cadario, now a Kim critic. “And if you live in a village, it is a really bad idea to have enemies.”

The bank had been designed around the idea that local needs, assessed by staff assigned to particular countries and regions, should dictate funding; cooperation across geographical lines required internal wrangling over resources. So Kim decided to dismantle existing networks. He brought in the management consulting firm McKinsey & Co, which recommended regrouping the staff into 14 “global practices”, each of which would focus on a policy area, such as trade, agriculture or water. Kim hired outsiders to lead some departments and pushed out several formerly powerful officials with little explanation. To symbolise that he was knocking down old walls, he had a palatial, wood-panelled space on the World Bank’s executive floor retrofitted as a Silicon Valley-style open-plan office, where he could work alongside his top staff.

Kim also announced that he would cut $400m in administrative expenses, and eliminate about 500 jobs – a necessary measure, he said, because low interest rates were cutting into the bank’s profits. Kim says he “made a very conscious decision to let anyone who wanted… air their grievances.” His opponents detected no such tolerance, however, and their criticisms turned ad hominem. Around Halloween in 2014, a satirical newsletter circulated among the staff, depicting Kim as Dr Frankenstein: “Taking random pieces from dead change management theories,” it read, “he and his band of external consultants cobble together an unholy creature resembling no development bank ever seen before.” Anonymous fliers attacking Kim also began to appear around bank headquarters.

Kim portrayed internal dissent as a petty reaction to perks such as travel per diems being cut. “There’s grumbling about parking and there’s grumbling about breakfast,” he told the Economist. Meanwhile, bank staffers whispered about imperial indulgences on Kim’s part, such as chartering a private jet. (Kim claims this is a longstanding practice among bank presidents, which he only uses when there are no other options.)

A French country officer named Fabrice Houdart emerged as a lead dissenter, broadcasting his frustrations with Kim in a blog on the World Bank’s intranet. In one post, he questioned whether “a frantic race to show savings… might lead to irreversible long-term damages to the institution.” (This being the World Bank, his sedition was often illustrated with charts and statistics.) The staff went into open rebellion after Houdart revealed that Bertrand Badré, the chief financial officer, whom Kim had hired and who was in charge of cutting budgets, had received a nearly $100,000 bonus on top of his $379,000 salary. Kim addressed a raucous town hall meeting in October 2014, where he told furious staffers, “I am just as tired of the change process as all of you are.”

A few months later, Houdart was demoted after being investigated for leaking a privileged document. The alleged disclosure was unrelated to Kim’s reorganisation – it had to do with Houdart’s human rights advocacy, for which he was well known at the bank – and Kim says the investigation began before Houdart’s denunciations of his presidency. Critics, however, portray it as retaliatory. “Fabrice has become a folk hero,” Cadario says, “because he was brave enough to say what many of the people within the bank are thinking.” (Houdart is currently disputing his demotion before an internal administrative tribunal.)

“It’s never fun when large parts of the organisation are criticising you personally,” Kim admits. Yet he maintains that his tough decisions were necessary. “In order to do a real change, you have to put jobs at risk,” he says. “And completely understandably, people hate that.”

In the heat of the staff revolt, Kim was devoting attention to a very different crisis: Ebola. In contrast with the bank’s historically cautious, analytical approach, Kim was pushing it to become more involved in emergency response. He committed $400m to confront the epidemic immediately, a quarter of which he pushed out in just nine days. He dispatched bank employees to afflicted west African countries and reproached the head of the WHO for the organisation’s lack of urgency. “Rather than being tied up in bureaucracy, or saying, ‘We don’t do those things,’ Jim is saying that if poor people’s lives are at risk… then it is our business,” says Tim Evans, whom Kim hired to run the bank’s new global practice for health.

Some bank veterans disagreed, vehemently. Nearly two years on, they still worry that in trying to save the day, Kim runs the risk of diverting the bank from its distinct mission. “Pandemic response is important – but it’s not the WHO, it’s the World Bank,” says Jean-Louis Sarbib, a former senior vice-president who now runs a nonprofit development consultancy. “I don’t think he understands the World Bank is not a very large NGO.” Referencing Kim’s work with Partners in Health, Sarbib adds, “The work of the World Bank is to create a system so that he doesn’t need to come and create a clinic in Haiti.”

In reply to this critique, Kim likes to cite a study co-written by a former World Bank economist, Larry Summers, that found that 24% of full-income growth in developing countries between 2000 and 2011 was attributable to improved public health. Put simply, Kim says, pandemics and other health deficits represent enormous threats to economic development, so they should be the World Bank’s business. The same goes for climate change, which the bank is fighting by funding a UN initiative to expand sustainable energy. As for violent conflicts, rather than waiting until the shooting has stopped and painstakingly preparing a post-conflict assessment – as the bank has done in the past – Kim wants to risk more capital in insecure zones.

“We… bought into this notion that development is something that happens after the humanitarian crisis is over,” Kim said at a recent event called the Fragility Forum, where he sat next to representatives of various aid groups and the president of the Central African Republic in the World Bank’s sun-soaked atrium. “We are no longer thinking that way.”

After the forum, amid a whirlwind day of meetings and speeches, Kim stopped at a hotel cafe with me to unwind for a few minutes. As a counterweight to his life’s demands, he practices Korean Zen-style meditation, but he also seems to blow off steam by brainstorming aloud. Goals and promises came pouring out of him like a gusher. Besides eliminating extreme poverty, which he has now promised will be done by 2030, Kim wants to raise incomes among the bottom 40% of the population in every country. He also wants to achieve universal access to banking services by 2020.

Long past our allotted interview time, Kim told me he had just one more idea: “Another huge issue that I want to bring to the table is childhood stunting.” At the Davos World Economic Forum this year, he explained, everyone was chattering about a “fourth industrial revolution”, which will centre on artificial intelligence, robotics and other technological leaps. But Kim thinks whole countries are starting out with a brainpower deficit because of childhood malnutrition. “These kids have fewer – literally fewer – neuronal connections than their non-stunted classmates,” he said. “For every inch that you’re below the average height, you lose 2% of your income.”

“This is fundamentally an economic issue,” he continued. “We need to invest in grey-matter infrastructure. Neuronal infrastructure is quite possibly going to be the most important infrastructure.”

To World Bank traditionalists, addressing nutrition is an example of the sort of mission creep that makes Kim so maddening. Despite its name and capital, the bank can’t be expected to solve all the world’s humanitarian problems. (“We are not the UN,” is an informal mantra among some staffers.) Poor countries may well prefer the bank to stick to gritty infrastructural necessities, even if Kim and his supporters have splashier goals. “The interests of its rich-country constituencies and its poor-country borrowers are diverging,” Pritchett says. “It’s like the bank has a foot on two boats. Sooner or later, it’s going to have to jump on one boat or the other, or fall in the water. So far, Jim Kim is just doing the splits.”

The World Bank headquarters in Washington. Photograph: Lauren Burke/AP

Kim’s defenders insist the bank hasn’t abandoned its core business. In fact, as private investment in emerging markets has contracted recently, due to instability in once-booming economies such as Brazil, countries have found more reasons to turn to the World Bank. Its primary lending unit committed $29.7bn in loans this fiscal year, nearly doubling the amount from four years earlier. “There is so much need in the world that I’m not worried we’re going to run out of projects to finance,” Kim says. He also hopes the worst of the tumult within the bank is over. A few elements of his reorganisation have been scaled back; after the new administrative structure proved unwieldy, the 14 global practices were regrouped into three divisions. Some of his more polarising hires have also left.

A five-year term, Kim says, is hardly sufficient to implement his entire agenda, and he has conveyed his desire to be reappointed in 2017. Though internal controversies have been damaging, and America’s domination of the bank remains a source of tension, the next US president (quite possibly Kim’s friend Hillary Clinton) will have a strong say in the matter. If he keeps his job, Kim wants to show that the World Bank can serve as a link between great powers and small ones, between economics and aid work – retaining its influence as old rules and boundaries are erased and new ones are scribbled into place.

Kim thinks he can succeed, so long as he keeps one foot rooted in his experiences as a doctor with mud between his toes. But he also wants to share his revelations about capital with his old comrades. “I really feel a responsibility to have this conversation with development actors who, like me 10 years ago, didn’t really understand the power of leverage,” Kim says with a guileless air.

“God,” he adds, “it is just such a powerful tool.”

Kim’s defenders insist the bank hasn’t abandoned its core business. In fact, as private investment in emerging markets has contracted recently, due to instability in once-booming economies such as Brazil, countries have found more reasons to turn to the World Bank. Its primary lending unit committed $29.7bn in loans this fiscal year, nearly doubling the amount from four years earlier. “There is so much need in the world that I’m not worried we’re going to run out of projects to finance,” Kim says. He also hopes the worst of the tumult within the bank is over. A few elements of his reorganisation have been scaled back; after the new administrative structure proved unwieldy, the 14 global practices were regrouped into three divisions. Some of his more polarising hires have also left.

A five-year term, Kim says, is hardly sufficient to implement his entire agenda, and he has conveyed his desire to be reappointed in 2017. Though internal controversies have been damaging, and America’s domination of the bank remains a source of tension, the next US president (quite possibly Kim’s friend Hillary Clinton) will have a strong say in the matter. If he keeps his job, Kim wants to show that the World Bank can serve as a link between great powers and small ones, between economics and aid work – retaining its influence as old rules and boundaries are erased and new ones are scribbled into place.

Kim thinks he can succeed, so long as he keeps one foot rooted in his experiences as a doctor with mud between his toes. But he also wants to share his revelations about capital with his old comrades. “I really feel a responsibility to have this conversation with development actors who, like me 10 years ago, didn’t really understand the power of leverage,” Kim says with a guileless air.

“God,” he adds, “it is just such a powerful tool.”

No comments:

Post a Comment