Labour party’s future lies with Momentum, says Noam Chomsky

Anushka Asthana in The Guardian

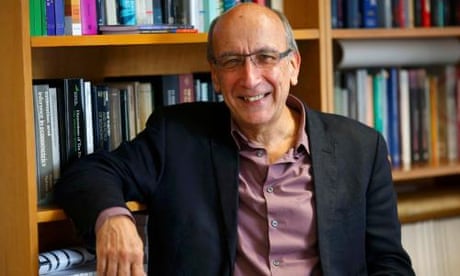

Professor Noam Chomsky has claimed that any serious future for the Labour party must come from the leftwing pressure group Momentum and the army of new members attracted by the party’s leadership.

In an interview with the Guardian, the radical intellectual threw his weight behind Jeremy Corbyn, claiming that Labour would be doing far better in opinion polls if it were not for the “bitter” hostility of the mainstream media. “If I were a voter in Britain, I would vote for him,” said Chomsky, who admitted that the current polling position suggested Labour was not yet gaining popular support for the policy positions that he supported.

“There are various reasons for that – partly an extremely hostile media, partly his own personal style which I happen to like but perhaps that doesn’t fit with the current mood of the electorate,” he said. “He’s quiet, reserved, serious, he’s not a performer. The parliamentary Labour party has been strongly opposed to him. It has been an uphill battle.”

He said there were a lot of factors involved, but insisted that Labour would not be trailing the Conservatives so heavily in the polls if the media was more open to Corbyn’s agenda. “If he had a fair treatment from the media – that would make a big difference.”

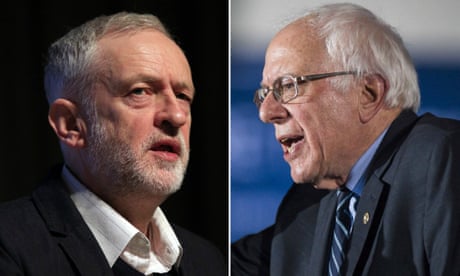

Asked what motivation he thought newspapers had to oppose Corbyn, Chomsky said the Labour leader had, like Bernie Sanders in the US, broken out of the “elite, liberal consensus” that he claimed was “pretty conservative”.

The academic, who is in Britain to deliver a lecture at the University of Reading on what he believes is the deteriorating state of western democracy, claimed that voters had turned to the Conservatives in recent years because of “an absence of anything else”.

“The shift in the Labour party under [Tony] Blair made it a pale image of the Conservatives which, given the nature of the policies and their very visible results, had very little appeal for good reasons.”

He said Labour needed to “reconstruct itself” in the interests of working people, with concerns about human and civil rights at its core, arguing that such a programme could appeal to the majority of people.

But ahead of what could be a bitter split within the Labour movement if Corbyn’s party is defeated in the June election, Chomsky claimed the future must lie with the left of the party. “The constituency of the Labour party, the new participants, the Momentum group and so on … if there is to be a serious future for the Labour party that is where it is in my opinion,” he said.

The comments came as Chomsky prepared to deliver a university lecture entitled Racing for the precipice: is the human experiment doomed?

He told the Guardian that he believed people had created a “perfect storm” in which the key defence against the existential threats of climate change and the nuclear age were being radically weakened.

“Each of those is a major threat to survival, a threat that the human species has never faced before, and the third element of this pincer is that the socio-economic programmes, particularly in the last generation, but the political culture generally has undermined the one potential defence against these threats,” he said.

Chomsky described the defence as a “functioning democratic society with engaged, informed citizens deliberating and reaching measures to deal with and overcome the threats”.

Professor Noam Chomsky has claimed that any serious future for the Labour party must come from the leftwing pressure group Momentum and the army of new members attracted by the party’s leadership.

In an interview with the Guardian, the radical intellectual threw his weight behind Jeremy Corbyn, claiming that Labour would be doing far better in opinion polls if it were not for the “bitter” hostility of the mainstream media. “If I were a voter in Britain, I would vote for him,” said Chomsky, who admitted that the current polling position suggested Labour was not yet gaining popular support for the policy positions that he supported.

“There are various reasons for that – partly an extremely hostile media, partly his own personal style which I happen to like but perhaps that doesn’t fit with the current mood of the electorate,” he said. “He’s quiet, reserved, serious, he’s not a performer. The parliamentary Labour party has been strongly opposed to him. It has been an uphill battle.”

He said there were a lot of factors involved, but insisted that Labour would not be trailing the Conservatives so heavily in the polls if the media was more open to Corbyn’s agenda. “If he had a fair treatment from the media – that would make a big difference.”

Asked what motivation he thought newspapers had to oppose Corbyn, Chomsky said the Labour leader had, like Bernie Sanders in the US, broken out of the “elite, liberal consensus” that he claimed was “pretty conservative”.

The academic, who is in Britain to deliver a lecture at the University of Reading on what he believes is the deteriorating state of western democracy, claimed that voters had turned to the Conservatives in recent years because of “an absence of anything else”.

“The shift in the Labour party under [Tony] Blair made it a pale image of the Conservatives which, given the nature of the policies and their very visible results, had very little appeal for good reasons.”

He said Labour needed to “reconstruct itself” in the interests of working people, with concerns about human and civil rights at its core, arguing that such a programme could appeal to the majority of people.

But ahead of what could be a bitter split within the Labour movement if Corbyn’s party is defeated in the June election, Chomsky claimed the future must lie with the left of the party. “The constituency of the Labour party, the new participants, the Momentum group and so on … if there is to be a serious future for the Labour party that is where it is in my opinion,” he said.

The comments came as Chomsky prepared to deliver a university lecture entitled Racing for the precipice: is the human experiment doomed?

He told the Guardian that he believed people had created a “perfect storm” in which the key defence against the existential threats of climate change and the nuclear age were being radically weakened.

“Each of those is a major threat to survival, a threat that the human species has never faced before, and the third element of this pincer is that the socio-economic programmes, particularly in the last generation, but the political culture generally has undermined the one potential defence against these threats,” he said.

Chomsky described the defence as a “functioning democratic society with engaged, informed citizens deliberating and reaching measures to deal with and overcome the threats”.

He blamed neoliberal policies for the breakdown in democracy, saying they had transferred power from public institutions to markets and deregulated financial institutions while failing to benefit ordinary people.

“In 2007 right before the great crash, when there was euphoria about what was called the ‘great moderation’, the wonderful economy, at that point the real wages of working people were lower – literally lower – than they had been in 1979 when the neoliberal programmes began. You had a similar phenomenon in England.”

Chomsky claimed that the disillusionment that followed gave rise to the surge of anti-establishment movements – including Donald Trump and Brexit, but also Emmanuel Macron’s victory in France and the rise of Corbyn and Sanders.

“The Sanders achievement was maybe the most surprising and significant aspect of the November election,” he said. “Sanders broke from a century of history of pretty much bought elections. That is a reflection of the decline of how political institutions are perceived.”

But he said the positions the US senator, who challenged Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination, had taken would not have surprised Dwight Eisenhower, who was US president in the 1950s.

“[Eisenhower] said no one belongs in a political system who questions the right of workers to organise freely, to form powerful unions. Sanders called it a political revolution but it was to a large extent an effort to return to the new deal policies that were the basis for the great growth period of the 1950s and 1960s.”

Chomsky argued that Corbyn stood in the same tradition.