Our consultation is nearly finished when my patient leans forward, and says, “So, doctor, in all this time, no one has explained this. Exactly how will I die?” He is in his 80s, with a head of snowy hair and a face lined with experience. He has declined a second round of chemotherapy and elected to have palliative care. Still, an academic at heart, he is curious about the human body and likes good explanations.

“What have you heard?” I ask. “Oh, the usual scary stories,” he responds lightly; but the anxiety on his face is unmistakable and I feel suddenly protective of him.

“Would you like to discuss this today?” I ask gently, wondering if he might want his wife there.

“As you can see I’m dying to know,” he says, pleased at his own joke.

If you are a cancer patient, or care for someone with the illness, this is something you might have thought about. “How do people die from cancer?” is one of the most common questions asked of Google. Yet, it’s surprisingly rare for patients to ask it of their oncologist. As someone who has lost many patients and taken part in numerous conversations about death and dying, I will do my best to explain this, but first a little context might help.

Some people are clearly afraid of what might be revealed if they ask the question. Others want to know but are dissuaded by their loved ones. “When you mention dying, you stop fighting,” one woman admonished her husband. The case of a young patient is seared in my mind. Days before her death, she pleaded with me to tell the truth because she was slowly becoming confused and her religious family had kept her in the dark. “I’m afraid you’re dying,” I began, as I held her hand. But just then, her husband marched in and having heard the exchange, was furious that I’d extinguish her hope at a critical time. As she apologised with her eyes, he shouted at me and sent me out of the room, then forcibly took her home.

It’s no wonder that there is reluctance on the part of patients and doctors to discuss prognosis but there is evidence that truthful, sensitive communication and where needed, a discussion about mortality, enables patients to take charge of their healthcare decisions, plan their affairs and steer away from unnecessarily aggressive therapies. Contrary to popular fears, patients attest that awareness of dying does not lead to greater sadness, anxiety or depression. It also does not hasten death. There is evidence that in the aftermath of death, bereaved family members report less anxiety and depression if they were included in conversations about dying. By and large, honesty does seem the best policy.

Studies worryingly show that a majority of patients are unaware of a terminal prognosis, either because they have not been told or because they have misunderstood the information. Somewhat disappointingly, oncologists who communicate honestly about a poor prognosis may be less well liked by their patient. But when we gloss over prognosis, it’s understandably even more difficult to tread close to the issue of just how one might die.

Thanks to advances in medicine, many cancer patients don’t die and the figures keep improving. Two thirds of patients diagnosed with cancer in the rich world today will survive five years and those who reach the five-year mark will improve their odds for the next five, and so on. But cancer is really many different diseases that behave in very different ways. Some cancers, such as colon cancer, when detected early, are curable. Early breast cancer is highly curable but can recur decades later. Metastatic prostate cancer, kidney cancer and melanoma, which until recently had dismal treatment options, are now being tackled with increasingly promising therapies that are yielding unprecedented survival times.

But the sobering truth is that advanced cancer is incurable and although modern treatments can control symptoms and prolong survival, they cannot prolong life indefinitely. This is why I think it’s important for anyone who wants to know, how cancer patients actually die.

‘Cancer cells release a plethora of chemicals that inhibit appetite and affect the digestion and absorption of food’ Photograph: Phanie / Alamy/Alamy

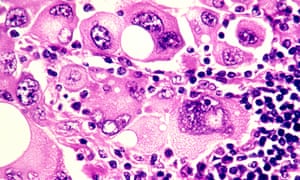

“Failure to thrive” is a broad term for a number of developments in end-stage cancer that basically lead to someone slowing down in a stepwise deterioration until death. Cancer is caused by an uninhibited growth of previously normal cells that expertly evade the body’s usual defences to spread, or metastasise, to other parts. When cancer affects a vital organ, its function is impaired and the impairment can result in death. The liver and kidneys eliminate toxins and maintain normal physiology – they’re normally organs of great reserve so when they fail, death is imminent.

Cancer cells release a plethora of chemicals that inhibit appetite and affect the digestion and absorption of food, leading to progressive weight loss and hence, profound weakness. Dehydration is not uncommon, due to distaste for fluids or an inability to swallow. The lack of nutrition, hydration and activity causes rapid loss of muscle mass and weakness. Metastases to the lung are common and can cause distressing shortness of breath – it’s important to understand that the lungs (or other organs) don’t stop working altogether, but performing under great stress exhausts them. It’s like constantly pushing uphill against a heavy weight.

Cancer patients can also die from uncontrolled infection that overwhelms the body’s usual resources. Having cancer impairs immunity and recent chemotherapy compounds the problem by suppressing the bone marrow. The bone marrow can be considered the factory where blood cells are produced – its function may be impaired by chemotherapy or infiltration by cancer cells.Death can occur due to a severe infection. Pre-existing liver impairment or kidney failure due to dehydration can make antibiotic choice difficult, too.

You may notice that patients with cancer involving their brain look particularly unwell. Most cancers in the brain come from elsewhere, such as the breast, lung and kidney. Brain metastases exert their influence in a few ways – by causing seizures, paralysis, bleeding or behavioural disturbance. Patients affected by brain metastases can become fatigued and uninterested and rapidly grow frail. Swelling in the brain can lead to progressive loss of consciousness and death.

In some cancers, such as that of the prostate, breast and lung, bone metastases or biochemical changes can give rise to dangerously high levels of calcium, which causes reduced consciousness and renal failure, leading to death.

Uncontrolled bleeding, cardiac arrest or respiratory failure due to a large blood clot happen – but contrary to popular belief, sudden and catastrophic death in cancer is rare. And of course, even patients with advanced cancer can succumb to a heart attack or stroke, common non-cancer causes of mortality in the general community.

You may have heard of the so-called “double effect” of giving strong medications such as morphine for cancer pain, fearing that the escalation of the drug levels hastens death. But experts say that opioids are vital to relieving suffering and that they typically don’t shorten an already limited life.

It’s important to appreciate that death can happen in a few ways, so I wanted to touch on the important topic of what healthcare professionals can do to ease the process of dying.

In places where good palliative care is embedded, its value cannot be overestimated. Palliative care teams provide expert assistance with the management of physical symptoms and psychological distress. They can address thorny questions, counsel anxious family members, and help patients record a legacy, in written or digital form. They normalise grief and help bring perspective at a challenging time.

People who are new to palliative care are commonly apprehensive that they will miss out on effective cancer management but there is very good evidence that palliative care improves psychological wellbeing, quality of life, and in some cases, life expectancy. Palliative care is a relative newcomer to medicine, so you may find yourself living in an area where a formal service doesn’t exist, but there may be local doctors and allied health workers trained in aspects of providing it, so do be sure to ask around.

Finally, a word about how to ask your oncologist about prognosis and in turn, how you will die. What you should know is that in many places, training in this delicate area of communication is woefully inadequate and your doctor may feel uncomfortable discussing the subject. But this should not prevent any doctor from trying – or at least referring you to someone who can help.

Accurate prognostication is difficult, but you should expect an estimation in terms of weeks, months, or years. When it comes to asking the most difficult questions, don’t expect the oncologist to read between the lines. It’s your life and your death: you are entitled to an honest opinion, ongoing conversation and compassionate care which, by the way, can come from any number of people including nurses, social workers, family doctors, chaplains and, of course, those who are close to you.

Over 2,000 years ago, the Greek philosopher Epicurus observed that the art of living well and the art of dying well were one. More recently, Oliver Sacks reminded us of this tenet as he was dying from metastatic melanoma. If die we must, it’s worth reminding ourselves of the part we can play in ensuring a death that is peaceful.

Stuart Broad and Joe Root played key roles in the Ashes win, but neither man made the BBC Sports Personality shortlist © Getty Images

Stuart Broad and Joe Root played key roles in the Ashes win, but neither man made the BBC Sports Personality shortlist © Getty Images