Advances in science are keeping us alive for longer and longer, but we are denied the right to die with dignity. It is grotesque

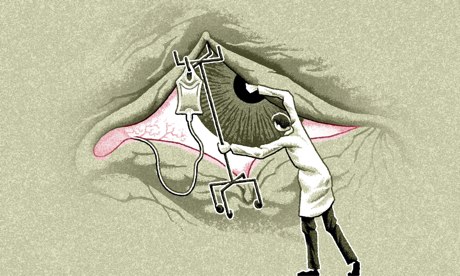

'Don't blame us if we are cluttering up the system. What we want and need is simple: a change in the law concerning assisted dying and voluntary euthanasia.' Illustration: Matt Kenyon

Back in the mid-70s, we were introduced to the notion of "medical nemesis" by the Austrian philosopher Ivan Illich. He warned us that doctors may do more harm than good, and that some diseases (which he labelled iatrogenic) were caused, not cured, by medical interventions. This doctrine has been widely accepted – we all know about the dangers of overprescribing antibiotics, about the risks of over-zealous or misinterpreted scans, about the creeping medicalisation of childbirth – but its application to old age and death is what interests me here. One of Illich's arguments in those days was that medicine, despite its apparent successes, was not notably increasing life expectancy. Alas, he was wrong. Artificially prolonged old age is the new iatrogenic malady.

We can't switch on the news without being told we will live longer, work longer, and survive on diminishing pensions or overpriced annuities. Newspaper columnists tell us we are selfish and that the young are suffering from our claiming an unfair share of state support. They begrudge us our bus passes, one of the few well-earned consolations of age. As we move into our unwanted last decade, we will, entirely predictably, become lonelier and lonelier and more and more likely to suffer from dementia and more and more expensive to maintain.

It would be unfair to blame doctors or health professionals for our longevity, which may be attributed to causes other than surgical ingenuity and pharmacological innovations and deadly life support machines, but it is not surprising that many of us feel gravely disappointed by the help and relief on offer to us at the end of life.

We look in vain for compassion, dignity, even common sense. We look in vain, despite what we are told, for adequate pain relief. Medical professionals seem far more interested in keeping alive barely viable premature "miracle" babies with a poor long-term prognosis than in offering reassurance to the growing and ageing multitudes who long to depart peacefully. They keep the babies alive because it's challenging, and very few people dare argue that it's not a good thing to do. They keep us alive because they are forbidden to give us what we want and need, and they are too frightened to question the law. There's something wrong there.

Don't blame us if we are cluttering up the system. What we want and need is simple. We want a change in the law concerning assisted dying and voluntary euthanasia, and help, if need be, to die with dignity.

The groundswell of opinion in favour of change is unmistakable. How often do you hear phrases like "you wouldn't let your dog suffer like that"? Three-quarters of the population backed Lord Falconer's assisted dying bill on its first reading in parliament. The bill would allow people who are terminally ill to receive the help they need to die, if that is what they choose. But can we have what we want? No. The politicians won't let us, the bishops won't let us, the health professionals aren't allowed to let us. It's grotesque.

Those suffering from incurable diseases need to be able to choose without penalty the help which they are at the moment denied. The elderly need to be able to plan ahead clearly, and to make their own choices about when their lives are no longer worth living. There seems to be some conspiracy to stop us thinking about the end game we all shall play. So we shuffle on, until it's too late to make any decisions at all, and we become helpless pawns in the politics of deferral, and utterly dependent on the humiliating procedures that for all our rational life we so wished to avoid.

It is my hope that in my lifetime the law will change, taking with it the fears that add so much terror to death. How wonderful it would be, if we knew that we would not be obliged to contemplate the bodily and mental decay that threatens us all. That we could opt out, and make our quietus, not with a bare bodkin or a plastic bag, or by jumping off the top of a multistorey car park, but with a nice glass of whisky and a pleasing pill – and so good night. How the heart would lift with joy at the good news. I don't go for Martin Amis's suicide booths, but I'm with Will Self all the way about the right to die when and how we want. When it's time to go, let's just go.

At the moment, it's not that easy. My husband, Michael Holroyd, fondly believes that as the longest serving patron of the Dignity in Dying campaigning organisation, he will be allowed to die in peace, but no, the doctors, in mortal fear of parliament, the law, the press and the General Medical Council, will be slavishly working to rule and obeying orders and striving officiously to keep him alive as they observe their archaic Hippocratic oath. It will be just like it was in the old days, when Simone de Beauvoir described her mother's death, in the ironically titled A Very Easy Death. If a woman of her intellect and clout couldn't prevent her mother from being hacked about by surgeons on her deathbed, what hope have we?

The best new year's gift an ageing population could receive is the right to die. As the philosopher Joseph Raz argues "The right to life protects people from the time and manner of their death being determined by others, and the right to euthanasia grants each person the power to choose themselves that time and manner." The right to die is the right to live.

No comments:

Post a Comment