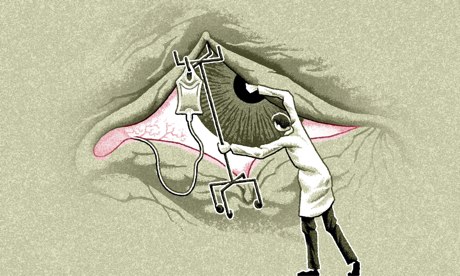

Is ranting at players during team talks like bloodletting in the age of quack doctors?

Shouting at players: Satisfying? Yes. Effective? No © AFP

Shouting at players: Satisfying? Yes. Effective? No © AFPThe subversive in me would love to whitewash over the usual clichés and catchphrases that are splashed on dressing-room walls and replace them with a more cynical message:

The six phases of a project:

1. Enthusiasm

2. Disillusionment

3. Panic

4. Search for the guilty

5. Punishment of the innocent

6. Rewards for the uninvolved

Not very cheering, I admit, but a salutary warning about our obsession with blame - a preoccupation sustained by dodgy narratives about "causes" that leads not to institutional improvement but to self-serving politics. Having pinned the blame on someone - rightly or, more likely, wrongly - the next task is "moving on". Sound familiar?

The "six phases" were attached to an office wall by an employee at the Republic Bank of New York. The story appears in Black Box Thinking, Matthew Syed's new book. Syed (a leading sports columnist and double Olympian) argues that our preoccupation with convenient blame - rather than openness to learning from failure - is a central factor holding teams and individuals back from improving. I think he is right.

Syed expresses admiration for the airline industry and its commitment to learning from failure - especially from "black boxes", the explosion-proof devices that record the conversations of pilots and other data. If the plane's wreckage is found, lessons - no matter how painful - must be learned. In the jargon, learning inside the aviation industry is an "open loop". (An "open loop" leads to progress because the feedback is rationally acted on; a "closed loop" is where failure doesn't lead to progress because weaknesses are ignored or errors are misinterpreted.) Syed presents harrowing examples from hospital operating theatres, of "closed loops" costing lives. Indeed, with its recurrent plane crashes and botched operations, the book takes the search for transferrable lessons to harrowing extremes.

One question prompted by Black Box Thinking is why is sport is not instinctively enthusiastic about evidence-based discussion. You might think that sports teams would be so keen to improve that they would rush to expose their ideas to rational and reflective scrutiny. But that's not always the case. As a player I often felt that insecure teams shrank from critical thinking, where more confident teams encouraged it.

The first problem sport has with critical thinking is the "narrative fallacy" (a concept popularised by Nassim Taleb). Consider this statement, thrown at me by a coach as I left the dressing room and walked onto the field after winning the toss and deciding to bowl first: "We need to have them five wickets down at lunch to justify the decision."

Hmm. First, even thinking about "justifying" a decision is an unnecessary distraction. Secondly, it's also irrational to think that the fact of taking five wickets, even if it happens, proves the decision was right. I might have misread the wicket, which actually suited batting first, but the opposition might have suffered a bad morning - five wickets could fall and yet the decision could still easily be wrong.

Alternatively, the wicket might suit bowling - and hence "justify" my decision - but we might bowl improbably badly and drop our catches. In other words, it could be the right decision even if they are no wickets down at lunch. What happened after the decision (especially when the sample of evidence is small or, as in this instance, solitary) does not automatically prove the rightness or wrongness of the decision.

Fancy theorising? Prefer practical realities? This kind of theorising, in fact, is bound up with very practical realities. Consider this example.

For much of medical history, bloodletting was a common and highly respected procedure. When a patient was suffering from a serious ailment and went to a leading doctor, the medical guru promptly drained significant amounts of blood from an already weak body. Madness? It happened for centuries.

And sometimes, if we don't think critically, it "works". As Syed points out, in a group of ten patients treated with bloodletting, five might die and five get better. So it worked for the five who survived, right?

Only, it didn't, of course. The five who were healed would have got better anyway (the body has great powers of self-recuperation). And some among the five who died were pushed from survival into death. Proving this fact, however, was more difficult - especially in a medical culture dominated by doctors who advocated and profited materially from bloodletting.

The challenge of demonstrating the real usefulness (or otherwise) of a procedure led to the concept of the "control group". Now imagine a group of 20 patients with serious illnesses - and split them into two groups, ten in each group. One group of ten patients gets a course of bloodletting, the other group of ten (the control group) does not. If we discover that five out of ten died in the bloodletting group and only three out of ten among the non-bloodletting group, then, at last, we have the beginnings of a proper evidence-based approach. The intervention (bloodletting) did more harm than simply doing nothing. It was iatrogenic.

Iatrogenic interventions are common in sport, too - such as when the coach tells a batsman to change his lifelong grip before making his Test debut. (Impossible? Exactly that happened to a friend of mine.) The angry team meeting is a classic iatrogenic intervention. Shouting at the team and vindictively blaming individual players, like bloodletting, provides the coach with the satisfying illusion that it works well sometimes. By "it works", we imply that the team in question played better after half-time or the following morning. Even having suffered an iatrogenic intervention, however, some teams - like some patients enduring bloodletting - inevitably play better afterwards. But on average, all taken together, teams would have playedbetter still without the distraction of a raging coach. (This insight helped win Daniel Kahneman a Nobel Prize, as I learned when I interviewed him.)

The great difficulty of sport, of course, is the challenge of conducting a proper control group experiment - because the game situation, pressures and circumstances are seldom exactly the same twice over. However, merely being open to the logic of these ideas, constantly exposing judgements and intuitions to critical thinking, takes decision-makers a good step in the direction of avoiding huge errors of conventional thinking.

That is why much of what Syed calls "black box thinking" could, I think, be filed under "critical thinking" - the desire to refine and improve one's system of thought as you are exposed to new experiences and ideas. Here is a personal rule of thumb: critical thinkers are also the best company over the long term. Critical thinkers are not only better bets professionally, they are also more interesting friends. Who wants to listen to the same set of unexamined views and sacrosanct opinions for decades? If you believe that your ideas don't ever need to evolve and adapt, can we at least skip dinner?

It is hard to imagine how anyone who is interested in leadership, innovation or self-improvement could fail to find something new and challenging in this book. Rather than presenting a simplistic catch-all solution, Syed takes us on a modern and personal walk through the scientific method. The book makes an interesting contrast with Syed's first book,Bounce, which proposed that talent is a myth - an argument that can be summed up in a single, seductive phrase: genius is a question of practice.

Rather than presenting a single idea, Black Box Thinking circles around a main theme - illustrating and illuminating it by drawing on a dizzyingly wide and eclectic series of ideas, case studies and lines of philosophical enquiry. The reader finishes the book with a deeper understanding of how he might improve and grow over the long term, rather than the transient feeling of having all his problems solved. The author, we sense, has experienced a similar journey while writing the book. Syed doesn't just preach black-box thinking, he practises it.