Reneé Earls has lived her whole life in west Texas, and watched oil booms come and go, but she has never seen anything like the buzz of activity in the industry today. “We are a hopping spot,” she says. “If you’re not working here, that’s because you’re not looking for a job, or you are unemployable . . . If you have a skill and want to work, you can name your price.”

Ms Earls is chief executive of the chamber of commerce in Odessa, in the heart of the Permian basin, the shale formation stretching from west Texas into New Mexico that is the red-hot centre of the latest US oil boom. Production in the region rose by 1m barrels a day in the year to August, contributing to a record-breaking 2.1m b/d increase in US output that has made the country the world’s largest crude producer.

The shale boom has not only transformed once rundown towns deep in the west Texas desert; it is increasingly reshaping the landscape of international politics. The emergence of the US as a born-again energy superpower — one of the key factors in the recent fall in oil prices — has led politicians in Washington to weigh how it might reshape some of its oldest alliances, raising uncomfortable questions for the oil producers of the Middle East .

For Saudi Arabia, the US’s chief ally in the Arab world, the past two months have delivered a stark lesson in how its relationship with Washington has been redefined by the Texas oil revolution.

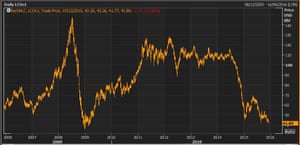

On Thursday and Friday ministers from Opec, the oil cartel that controls roughly a third of global production, and its allies including Russia and Kazakhstan, will meet in Vienna to decide how to respond to the 30 per cent plunge in oil prices to around $60 a barrel over the past two months. With US output surging, and Russia and Saudi Arabia also producing at close to record levels, traders are convinced the market will be awash with oil next year.

Previously such a fall would have prompted Opec and its allies to agree to cut production. But for Saudi Arabia, which remains the world’s top oil exporter and the cartel’s de facto leader, that decision has been complicated by the murder of Jamal Khashoggi.

The gruesome killing of the Saudi Arabian journalist and Washington Post columnist, a critic of the royal family, has revealed fissures in its prized relationship with the US.

US president Donald Trump has maintained his backing for Riyadh and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the country’s day-to-day ruler widely known as MBS, despite reports that the CIA has concluded that he ordered the operation against Khashoggi at the kingdom’s consulate in Istanbul. But his stance comes with conditions attached, one of which lies at the heart of the kingdom’s wellbeing: the oil price.

In statements, tweets and private communications Mr Trump has made clear his support for lower oil prices and his opposition to Riyadh moving to cut production, heaping pressure on a royal court shaken by the international backlash against the Khashoggi killing. The pressure from the White House has come despite Saudi Arabia raising production this summer to help make sure the market remained well supplied as the US reimposed sanctions on Iran. Riyadh’s position as Tehran’s chief rival in the region reflects a core part of the Trump administration’s foreign policy.

“The priority for Saudi Arabia is shoring up MBS’s position, and the key part of that is securing Trump’s backing,” says Derek Brower, a director of RS Energy Group. “Trump has clearly linked his support for MBS with several things . . . but it’s oil that seems to be at the top of his agenda.”

For the Trump administration, the calculation is straightforward. Lower oil prices mean cheaper petrol, providing a boost for consumers. The president has hailed the recent fall in prices as a “tax cut”, giving him some good news after a stock market wobble triggered by his confrontation with China over trade.

For Saudi Arabia, that creates a dilemma. Khalid al-Falih, its energy minister, has pushed ahead with plans to drum up support for cutting oil production by more than 1m b/d, but observers think he will be constrained by the need to appease Mr Trump.

Bob McNally, a consultant who has advised US administrations on oil policy, says Riyadh’s position is precarious. “If they orchestrate a high-profile Opec-plus cut that boosts Brent crude back up towards $70 they risk Trump’s wrath,” he says. “[But] if Riyadh bends entirely to Trump’s will and keeps production at record levels, an inventory glut will return and the bottom will fall out of crude prices.”

Ellen Wald, author of a history of Saudi Arabia’s oil industry, says the “ultimate success” for Riyadh from this week’s meeting would be “to quietly let people know that a cut is happening to raise the price, without drawing attention to the activity of Opec specifically.”

Yet history suggests that kind of mixed message risks pleasing no one — angering Mr Trump while not doing much to raise prices.

The stakes for Saudi Arabia are higher than just a single decision on output. Its alliance with the US has long been underpinned by oil supplies, with the resultant petrodollars recycled back into the American economy through the purchase of military hardware.

After a fall in prices in 2014, Riyadh renewed its attempts to diversify and modernise both its economy and wider society, aiming to reduce its dependence on oil revenues. But for the programme to have a chance of success, Saudi Arabia needs a higher oil price in the short term to help fund the changes.

The shale boom is eroding the foundations of one of the pillars of the alliance. US net oil imports, which peaked at about 13m b/d in 2005, have dropped to about 2.4m b/d this year. By the end of next year, they could be running at just 330,000 b/d, according to the US Energy Information Administration.

Saudi Arabia’s crude supplies remain crucial to the world economy, and to US consumer fuel prices. But Amy Myers Jaffe, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, says the US economy is much less vulnerable to a spike in prices than it was even a decade ago.

The evidence of the crude price fall four years ago and subsequent recovery is that the impact of changes on the American economy is now roughly neutral. “The US is not in the position it was in 2007-08, when we were facing a rising oil price that put strain on the current account deficit and the dollar,” she says. “That’s a big change.”

As politicians start to grasp the implications of that shift, it is strengthening the argument that the US no longer needs to shackle itself to Riyadh.

“The atmosphere in Washington has certainly changed following the killing of Jamal Khashoggi,” says Helima Croft, a former CIA analyst who now runs RBC Capital Markets’ natural resources analysis. “Politicians see the surge in US oil production and are wondering aloud whether the alliance is as necessary as it once was.”

Those questions are also starting to drive activity in Congress. Last week, the Senate voted 63-37 to advance a resolution demanding that the president end US armed forces’ activity “in or affecting Yemen”, where Saudi Arabia’s war against Iran-aligned Houthi rebels has exacerbated what aid groups describe as the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

Legislation that would allow the US to impose criminal penalties on members of Opec and their allies for acting as a cartel has also been making progress. For Saudi Arabia, which has extensive assets in the US including the largest refinery in North America, that legislation is a genuine threat.

Tim Kaine, the Democratic senator from Virginia who was a co-sponsor of the bipartisan legislation on Yemen, suggested the Khashoggi death had been the last straw for some. “It was really important for the Senate to send a message to Saudi Arabia: ‘you do not have a free pass’,” Mr Kaine told National Public Radio last week. “The president’s signal of complete impunity is not in accord with American values.”

In the autumn of 2014, the Saudi government tried to reassert its authority in the oil market against the nascent threat from shale. As a global glut of crude swelled up, Riyadh declined to cut production, in the belief it could drown the Texas producers in a sea of cheap oil.

But shale proved far more resilient than Saudi Arabia — the only country with significant spare production capacity — had hoped. Two years on Opec members returned to restricting output, with the help of Russia and other non-member producers, to lay the foundations for a recovery in prices.

As the oil price has fallen this autumn, the memories of that episode have been resurfacing. But Jason Bordoff of Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy says there is at least one crucial difference. “We now know how resilient shale can be. We saw how companies could cut costs and become more efficient to keep producing. That complicates Opec’s decision-making,” he says. “This time around, Opec knows it can’t kill shale, but maybe just wound it.”

Ms Earls says the people of Odessa have been watching as oil prices have plunged in the past two months. Fundamentally, though, they “still feel very confident”, she adds, because of the producers’ long-term commitment. The Permian Strategic Partnership, an industry-backed group that works with communities to help develop badly-needed infrastructure including roads, houses and schools, estimates a further 60,000 jobs will be createdby 2025, a huge increase for an area that had a population of about 330,000 last year.

The rate at which new wells are brought into production in the Permian was already expected to slow, in part because of a shortage of pipeline capacity. If the fall in prices is sustained, it could mean the industry slows further across the US, raising questions too for the White House.

The gains to consumers from lower fuel prices will be offset by the hit to investment. The oil-dependent economies of Texas and North Dakota would bear the brunt of the hit, but it would also extend to other industries such as steelmaking, which has benefited from the boom in pipeline construction.

Bernadette Johnson, vice-president of market intelligence at Drillinginfo, a research group, says there are several oil producing regions, such as the Denver-Julesburg Basin of Colorado, Wyoming and Nebraska, where a fall in US crude from $60 to $50 would make a significant difference to the economics.

“The companies think that it may just be a temporary thing, and that prices will rebound,” she says. “If the oil price stays where it is, we will see companies start to react.”

Yet while there may be a temporary slowdown, there is a general confidence in the US industry that its growth can continue. US officials say they are not concerned about the impact of lower oil prices, arguing that the industry will be able to continue to grow thanks to technological improvements and efficiency gains. Others are more sceptical, noting that US production contracted in 2016 when prices were at their nadir.

Will Giraud, executive vice-president of Concho Resources, one of the leading producers in the Permian Basin — where production is approaching 3.7m b/d — told investors last month: “I think there are several more years of very high growth, and it’s likely that the Permian gets into the 5m-6m or maybe even 7m b/d of production and then sustains that for a decent period.”

In the face of rampant US shale output, Saudi Arabia looks like it may still decide that angering Mr Trump is a price worth paying for a production cut that props up the oil price, whatever the heightened risks from the Khashoggi affair. But regardless of what the Saudis decide, the flow of oil from places such as Odessa will keep quietly eroding one of the old certainties that underpinned their relationship with the US. As Mr Brower at RS Energy puts it: “The pressures that Saudi Arabia are under are already immense.”