The UK drinks industry lobbied vigorously against a minimum price. Photograph: Johnny Green/PA

It was a classic exchange. Neil Goulden, chair of the Association of British Bookmakers, did his best to defend the indefensible. We must place the problem of addictive fixed-odds betting machines in context, he told Radio 4's Today programme last week. They constitute only a small part of the industry's total revenues; there are very few problem gamblers. Britain has the best regulated and most socially responsible gaming industry in the world. Obviously voluntary efforts, which had already achieved much, needed to go further. But there was no need for more intervention.

Later, in the House of Commons, the prime minister, keenly aware that Ed Miliband has thrived when combining the cost of living crisis with example after example of predatory capitalism, was not going to allow himself to be painted as the friend of the betting and casino industries. But equally, he had to keep alive his deep conviction that regulation, always " burdensome", should be avoided as a matter of principle and, if conceded, kept as minimal as possible.

Yes, he understood the leader of the opposition's concern that ordinary high-street betting shops were being turned into mini-casinos via these machines and were proliferating in some of the most deprived parts of the country. But a "review", he claimed, of unspecified provenance was under way. There was no need to support the Labour party's proposals. The issue was kicked into the long grass.

Last week witnessed a procession of examples where successive industries demonstrated their unnerving and effective capacity to block efforts at making them work more in the social and public interest. The

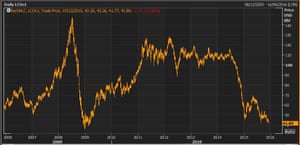

British Medical Journal revealed in a powerful article that the UK drinks industry had enjoyed no fewer than

130 meetings with ministers in the run-up to last July's abandonment of the commitment to set a minimum price of 40p for an unit of

alcohol. The evidence from Sheffield University's alcohol research department is unambiguous: the higher the price, the less is consumed, lowering crime and death rates alike.

Yet purposeful intervention even for these high stakes is not what Conservative ministers or rightwing thinktanks believe in. Better a world of voluntary codes of practice and forums promoting responsibility than anything with teeth that might "burden" business or – shedding crocodile tears – "penalise the poor". Indeed, it was in precisely those terms that the health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, discussed minimum alcohol pricing with Asda chief executive, Andy Clarke. In case we were in any doubt, the public health minister,

Jane Ellison, spelled out the Conservative position, preferring a " collaborative approach on public health" in a "voluntary way" in which business is a "partner".

Collaboration, voluntary, partnership and social responsibility are good words. Regulation, legislation, quotas and tax are bad words, for, it is alleged, these are just the sort of things to raise prices and disadvantage hard-pressed consumers. Thus already the sugar industry, confronting the newly created

Action on Sugar Campaign to lower the sugar content in food, is reaching for the same Goulden armament. British housebuilders, fighting off proposals to landscape new developments so that rainwater runs off naturally, plead that house prices will rise as a result, and thus four years after the

2010 Flood Defence Act, requiring such development to improve our much-depleted flood defences, there is still no agreement.

Part of the problem is that in the indiscriminate drive to create a smaller government, the

Department of the Environment, reeling from cuts, has not the manpower to follow through on legislation. But the problem is made worse because the environment secretary,

Owen Paterson, believes, like Jeremy Hunt at health and many other colleagues, that essentially their job is to do whatever business says.

Obviously in a capitalist economy, private business is a principal driver of growth. Great entrepreneurship in action is fabulous, but crucially it never emerges from private action alone. There is always some pubic agency involved in, and often leading, the risk-taking. Yet the fiction of our times is that all business is entrepreneurial, all business aims to behave well, all business accepts that it should pay the social costs of its activities and that any effort to shape business activity is counterproductive. These are the propositions that underpin the stance of the business lobbyist – and of the minister welcoming him or her. The public, if it only knew, would surely despair.

The lack of regulation and legislation for which the business lobbyists press is rarely to support entrepreneurship; in most instances, it is a sophisticated form of corporate welfare. It will not be British bookmakers who pick up the costs of addictive gambling in welfare bills and housing benefit; no drinks company will foot the NHS's bill for alcohol-related illness or police bill for crime; no sugar company the bill for obesity. Housebuilders will cheerfully direct rainwater cheaply into the sewerage system and the water companies will then raise water charges and expect state guarantees for improving the system.

The deal is clear: pass on the maximum cost to the state, minimise one's own obligations including tax payments, and insist anything else will cost jobs and penalise consumers. Corporate welfare works. Bookmaker William Hill, for example, declares £293m profit on a turnover of £1.3bn, and pays a mere £48m in tax. Drinks multinational Diageo pays £66m of UK tax on its £1.75 bn of UK turnover. Executive pay is stunning; indeed, it even provoked a

shareholder revolt at William Hill last year.

The low regulation lobby is in effect creating high-return, low-risk business fiefdoms largely free of social and public obligations. Worse, shareholders and investors set these returns against what they might expect investing in frontier technologies and innovation. Why do that when you can make more certain and higher profits in pay-day lending, bookmaking or the drinks business? The Cameron-Osborne-Hunt-Paterson mantra leads straight to a low innovation economy and a high-stress, low-wellbeing society, while offering unnecessarily high returns to those at the top.

Reality is very different. Business is part of the society in which it trades. Regulation and legislation, far from burdens, are crucial grit in the capitalist oyster. They are proposed in our democracy because they will reduce public and social costs that otherwise society has to bear. By obliging business to accept the costs it creates, it raises genuine innovation. It is time to call time. We don't want ministers acting as surrogate corporate lobbyists. We need them to fashion a new compact between business and society.