BY

Asked how he assesses his teachers, Mr Matti Koivusalo shrugs matter-of-factly that he has “no means” to do so. “There is no evaluation whatsoever for teachers. Everything is based on trust,” says the Principal of Haaga Comprehensive School in Helsinki.

Indeed, the “open” school culture means any feedback quickly reaches his ears, says Mr Koivusalo, who looks after 50 teachers and 600 pupils in grades one through nine (the equivalent of Primary 1 to Secondary 3 in Singapore).

It is easy to see how: Along the school’s hallway, pupils look up from their mobile phones and greet him as he walks past; some engage him in friendly banter. At the school cafeteria where free lunches are served daily — an established practice at all Finnish schools — teachers join him for lunch and chat about how their day has gone.

Said Mr Koivusalo: “If something bad happens, I’ll hear about it in five minutes … The atmosphere is such that (students and teachers) can come and talk about it freely without being afraid.”

Even so, sackings are rare in Finnish schools, say educators. Mr Vesa Valkila, one of the principals at Turku University teacher training school, tried to explain: “Finnish teachers have a lot of freedom and are trusted … that really motivates a lot of them to do their best.”

LEFT TO TEACH

In Finland, a small country of 5.4 million people, its education system operates on this singular principle of trust.

The country’s model shot to global attention after Finnish pupils repeatedly excelled in international tests such as the Programme for International Student Assessment — despite having practically no mandated standardised exams, rankings or competition.

Schools take in students of all varying abilities, including those with learning disabilities, under one roof. The curious result is that, the differences between its weakest and strongest students are the smallest in the world, according to a Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) survey.

School leaders across Finland tell TODAY the same thing: “We trust our teachers”.

There are no national examinations in the first nine years of Finnish formal schooling, and schools and teachers are pretty much left on their own to educate their charges.

As Ms Armi Mikkola, counsellor of education at the Ministry of Education and Culture put it: “The administration is for support and not for inspection … Trust is part of Finnish society, it is a culture.”

Nevertheless, “with trust, there are some risks”, admitted Professor Jouni Valijarvi, Director of the Finnish Institute for Educational Research.

To mitigate risks of having underperforming teachers in schools, a stringent teacher selection process and rigorous teacher training is integral to the system, he said. “It is very important that we can say all schools are good schools,” added Prof Valijarvi. “Because in every school, we’ve highly-trained and qualified teachers”.

SELECTING THE VERY BEST

Yearly, 7,000 teaching aspirants apply to be class teachers (teaching the equivalent of Primary 1 to 6). Typically, there are just 800 spots available.

To teach secondary and upper secondary students (Secondary 1 to Junior College equivalent), 6,000 vie for 1,500 subject teacher positions yearly. Universities cherry-pick from this large pool of applicants, with two different selection processes for each category.

For class teachers, to prepare applicants for an entrance test, authorities will release study materials online on education-related topics such as pedagogical research studies. During the four-hour test, applicants answer about 100 multiple-choice questions. Even so, acing the entrance test does not guarantee a spot in one of the 11 universities offering teacher education.

In phase two, depending on the applicant’s university of choice (they are given up to three picks), there could be a psychometric test along with an interview, or an observed group activity. Some universities also select based on an applicant’s matriculation exam results — the only national examinations taken by Finnish pupils, at the age of 18.

Ms Anna Vaatainen, a student teacher at the University of Turku, is one who succeeded on her second try.

In her first attempt, she was invited by the University of Jyvaskyla for an interview but did not make it through. She went on to obtain a social work degree, and worked in an orphanage for four months, before deciding to give teacher education another go.

This time, after “studying very hard” for the entrance test again, she and three other applicants were tasked by the University of Turku to plan an imaginary school’s sports day. “I am better around people so this group activity might have worked for me,” she said.

Those hoping to be a subject teacher undergo a similar selection process, having to first pass an entrance test set by their subject faculty of choice. They will then apply to the faculty of education, which may require an aptitude test and interview.

The result is that you ensure true commitment to the job. Mr Jari Kouvalainen, a student teacher at the University of Eastern Finland, said: “Because we have to get through this really hard test, you have to be really motivated. With another five years of study, you’re really committed to this career”.

RESEARCH-BASED TRAINING

In the ’70s, Finnish officials moved teacher training under the universities, subsequently implementing a five-year master’s degree programme for all who want to become teachers. A combination of theory, practice and research was key to teacher education, they decided.

Class teachers major in the educational sciences and teach most subjects including Mathematics and Science at the primary levels. Teacher educators say that teaching younger children requires strong pedagogical skills to motivate and excite learners, and not just the transfer of academic knowledge at this stage.

By contrast, subject teachers major in their teaching subjects, while also having to complete pedagogical modules and teaching practicums. In-depth knowledge in their teaching areas is crucial, to give them the confidence to explain complex theories and tackle difficult questions.

Ms Anneli Rautiainen, head of professional development of teachers at the Finnish National Board of Education, thinks that research-based teacher education accounts for the high quality of teaching in Finnish schools today.

“The fact that we have a Master’s degree for teacher initial education is very important. As research-based teachers, they can analyse learning situations and know how to support their students better,” she said.

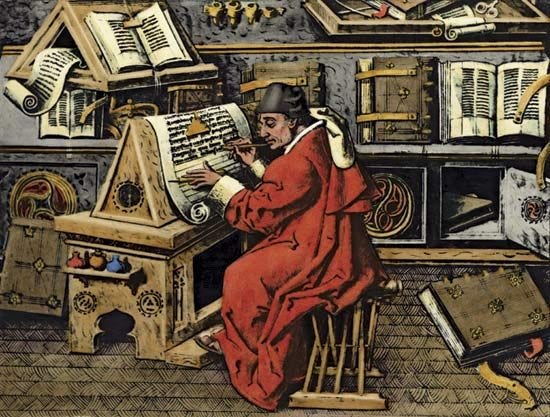

Student teacher Ms Tuula Hurtig agrees that conducting research has honed her critical thinking abilities and improved her teaching methods. Graduating as a history and civics teacher this year, her thesis involved research into how historical pictures impacted her students’ learning.

GETTING FIELD EXPERIENCE

Head of teacher education at University of Helsinki, Professor Jari Lavonen, calls research-based teacher education vital — it combines with field practice to keep student-teachers in touch with classroom realities and “thinking about their teaching methods”, he said.

All student teachers undergo multiple teaching practicums as part of their five-year programme. Each one lasts between two weeks and a year.

Guided by teacher mentors, student teachers are attached to teacher-training schools set up by the universities, where they plan, teach and observe lessons. These 12 teacher training schools across Finland function as normal schools, with pupils coming from nearby homes. These schools also partner regularly with universities to produce the latest research in education.

Final-year student teacher Mikko Honkamaki, from the University of Jyvaskyla, worked with different mentors during each of his four practicuums — which broadened his perspective on various teaching styles — and got advice before and after each lesson. He also got to observe and critique fellow student-teachers, and vice-versa.

“Watching my peers forced me to focus on my own way of giving instructions ... Receiving and giving feedback has also been crucial to my growth as a professional,” he said.

LEEWAY TO DECIDE

It was a cold winter’s morning when TODAY visited Maininki School in Espoo city, half an hour outside Helsinki, and Ms Rose-Marie Mod-Sandberg was conducting an English Language lesson with her eight-graders (Secondary 2 equivalent).

The classroom was quiet as some students had fallen ill; it was a smaller than usual group. Ms Mod-Sandberg, 55, decided to get her pupils to share about their favourite American cities and imagine what they would do if they got there. As the mood lightened, she gave out worksheets which each student completed on their own.

She has the leeway to tailor her lessons according to her students’ abilities or interests on that very day itself, she told us. For instance, if the children were keen on a topic that was meant only for next year, she could dive into it. And if they seemed more tired than usual — such as after a strenuous Physical Education lesson — she could choose to do something less demanding, and pick things up later.

“If I want to teach a topic, I can teach it anyway and anytime I like,” she said. “Finnish teachers undergo a long training, so (school leaders) can trust us to be professional and to act in the pupils’ interest”.

MORE THAN MONEY’S WORTH

In Finnish schools, teachers typically teach from 8am to 2pm before heading off to plan lessons or attend to parents’ queries. They are not required to take charge of after-school activities such as arts or sports clubs — usually run by private community organisations — and those who do so, are remunerated accordingly.

Schools leaders also said that a layer of stress is removed for teachers as there is no evaluation process linked to their salaries. In fact, the pay structure is relatively flat where pay increases with years of experience and teaching hours.

According to the latest OECD data, Finland’s average annual wage is S$59,852 or approximately S$5,000 a month. For those teaching at the primary level, annual salaries start at S$35,883 (about S$ 3,000 a month). After 20 years, their pay reaches a maximum level of S$64, 530 (S$5,400 a month).

Nevertheless, pay is not a main issue for Finnish teachers, said those TODAY spoke to. People are attracted to the career due to the high status that education is accorded in Finland and the autonomy given to teachers.

The government provides free education in the first nine years of a child’s school life, while schools receive funds to invest in slower learners. Teachers also hold a place in Finnish history, often cited as important figures alongside priests and doctors.

“Young people still see working as a teacher as very creative and independent, where teachers can make a difference in their pupils’ lives,” said Mr Olli Maatta, a teacher trainer at Helsinki Normal Lyceum, a regular Finnish school owned by the University of Helsinki for trainee teachers to serve their attachments.

At Haaga Comprehensive School, the school bell rings and children burst out of their classrooms into the snow-filled courtyard, throwing snowballs at one another and sledding down mini snow hills.

Starring out of his window as one of his teachers leads pupils back from a skiing lesson, principal Mr Koivusalo observes: “The role of an educator is very important. If a teacher loves his job, the children know it and they will want to come to school.”

Ng Jing Yng is a senior reporter with TODAY covering the education beat. She spent one and a half weeks visiting schools in three Finnish cities — Helsinki, Jyvaskyla and Turku — ranging from primary through to upper secondary (JC equivalent) levels. She spoke to students, educators, university faculty who train teachers and officials.