'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label textbook. Show all posts

Showing posts with label textbook. Show all posts

Tuesday, 26 August 2025

Sunday, 14 February 2021

Distorting Narratives for Nation States

Nadeem F Paracha in The Dawn

In the last few years, my research, in areas such as religious extremism, historical distortions in school textbooks, the culture of conspiracy theories and reactionary attitudes towards science, has produced findings that are a lot more universal than one suspected.

This century’s second decade (2010-2020) saw some startling political and social tendencies in Europe and the US, which mirrored those in developing countries. Before the mentioned decade, these tendencies had been repeatedly commented upon in the West, as if they were entirely specific to poorer regions. Even though many Western historians, while discussing the presence of religious extremism, superstition or political upheavals in developing countries, agreed that these existed in developed countries as well, they insisted that these were only largely present in their own countries during their teething years.

In 2012, at a conference in London, I heard a British political scientist and an American historian emphasise that the problems that developing countries face — i.e. religiously-motivated violence, a suspect disposition towards science, and continual political disruption — were present at one time in developed countries as well, but had been overcome through an evolutionary process, and by the construction of political and economic systems that were self-correcting in times of crisis. What these two gentlemen were suggesting was that most developing countries were still at a stage that the developed countries had been two hundred years or so ago.

However, eight years after that conference, Europe and the US, it seems, have been flung back two hundred years in the past. Mainstream political structures there have been invaded by firebrand right-wing populists, dogmatic ‘cultural warriors’ from the left and the right are battling it out to define what is ‘good’ and what is ‘evil’ — in the process, wrecking the carefully constructed pillars of the Enlightenment era on which their nations’ whole existential meaning rests — the most outlandish conspiracy theories have migrated from the edges of the lunatic fringe into the mainstream, and science is being perceived as a demonic force out to destroy faith.

Take for instance, the practice of authoring distorted textbooks. Over the years, some excellent research cropped up in Pakistan and India that systematically exposed how historical distortions and religious biases in textbooks have contributed (and still are contributing) to episodes of bigotry in both the countries. During my own research in this area, I began to notice that this problem was not restricted to developing countries alone.

In 1971, a joint study by a group of American and British historians showed that out of the 36 British and American school textbooks that they examined, no less than 25 contained inaccurate information and ideological bias. In 2007, the American sociologist James W. Loewen surveyed 18 American history texts and found them to be “marred by an embarrassing combination of blind patriotism, sheer misinformation, and outright lies.” He published his findings in the aptly titled book Lies My Teacher Told Me.

In 2020, 181 historians in the UK wrote an open letter demanding changes to the history section of the British Home Office’s citizenship test. The campaign was initiated by the British professor of history and archeology Frank Trentmann. A debate on the issue, through an exchange of letters between Trentmann and Stephen Parkinson, a former Home Office special adviser, was published in the August 23, 2020 issue of The Spectator. Trentmann laments that the problem lay in a combination of errors, omissions and distortions in the history section pages, which were also littered with mistakes.

Not only are historical distortions in textbooks a universal practice, but the many ways that this is done are equally universal and cut across competing ideologies. In Textbooks as Propaganda, the historian Joanna Wojdon demonstrates the methods that were used by the state in this respect in communist Poland (1944-1989).

The methods of distortions in this case were similar to the ones that were used in various former communist dictatorships such the Soviet Union and its satellite states in East Europe, and in China. The same methods in this context were also employed by totalitarian regimes in Nazi Germany, and in fascist Italy and Spain.

And if one examines the methods of distorting history textbooks, as examined by Loewen in the US and Trentmann in the UK, one can come across various similarities between how it is done in liberal democracies and how it was done in totalitarian set-ups.

I once shared this observation with an American academic in 2018. He somewhat agreed but argued that because of the Cold War (1945-1991) many democratic countries were pressed to adopt certain propaganda techniques that were originally devised by communist regimes. I tend to disagree. Because if this were a reason, then how is one to explain the publication of the book The Menace of Nationalism in Education by Jonathan French Scott in 1926 — almost 20 years before the start of the Cold War?

Scott meticulously examined history textbooks being taught in France, Germany, Britain and the US in the 1920s. It is fascinating to see how the methods used to write textbooks, described by Scott as tools of indoctrination, are quite similar to those applied in communist and fascist dictatorships, and how they are being employed in both developing as well as developed countries.

In a nutshell, no matter what ideological bent is being welded into textbooks in various countries, it has always been about altering history through engineered stories as a means of promoting particular agendas. This is done by concocting events that did not happen, altering those that did take place, or omitting events altogether.

It was Scott who most clearly understood this as a problem that is inherent in the whole idea of the nation state, which is largely constructed by clubbing people together as ‘nations’, not only within physical but also ideological boundaries.

This leaves nation states always feeling vulnerable and fearing that the glue that binds a nation together, through largely fabricated and manufactured ideas of ethnic, religious or racial homogeneity, will wear off. Thus the need is felt to keep it intact through continuous historical distortions.

In the last few years, my research, in areas such as religious extremism, historical distortions in school textbooks, the culture of conspiracy theories and reactionary attitudes towards science, has produced findings that are a lot more universal than one suspected.

This century’s second decade (2010-2020) saw some startling political and social tendencies in Europe and the US, which mirrored those in developing countries. Before the mentioned decade, these tendencies had been repeatedly commented upon in the West, as if they were entirely specific to poorer regions. Even though many Western historians, while discussing the presence of religious extremism, superstition or political upheavals in developing countries, agreed that these existed in developed countries as well, they insisted that these were only largely present in their own countries during their teething years.

In 2012, at a conference in London, I heard a British political scientist and an American historian emphasise that the problems that developing countries face — i.e. religiously-motivated violence, a suspect disposition towards science, and continual political disruption — were present at one time in developed countries as well, but had been overcome through an evolutionary process, and by the construction of political and economic systems that were self-correcting in times of crisis. What these two gentlemen were suggesting was that most developing countries were still at a stage that the developed countries had been two hundred years or so ago.

However, eight years after that conference, Europe and the US, it seems, have been flung back two hundred years in the past. Mainstream political structures there have been invaded by firebrand right-wing populists, dogmatic ‘cultural warriors’ from the left and the right are battling it out to define what is ‘good’ and what is ‘evil’ — in the process, wrecking the carefully constructed pillars of the Enlightenment era on which their nations’ whole existential meaning rests — the most outlandish conspiracy theories have migrated from the edges of the lunatic fringe into the mainstream, and science is being perceived as a demonic force out to destroy faith.

Take for instance, the practice of authoring distorted textbooks. Over the years, some excellent research cropped up in Pakistan and India that systematically exposed how historical distortions and religious biases in textbooks have contributed (and still are contributing) to episodes of bigotry in both the countries. During my own research in this area, I began to notice that this problem was not restricted to developing countries alone.

In 1971, a joint study by a group of American and British historians showed that out of the 36 British and American school textbooks that they examined, no less than 25 contained inaccurate information and ideological bias. In 2007, the American sociologist James W. Loewen surveyed 18 American history texts and found them to be “marred by an embarrassing combination of blind patriotism, sheer misinformation, and outright lies.” He published his findings in the aptly titled book Lies My Teacher Told Me.

In 2020, 181 historians in the UK wrote an open letter demanding changes to the history section of the British Home Office’s citizenship test. The campaign was initiated by the British professor of history and archeology Frank Trentmann. A debate on the issue, through an exchange of letters between Trentmann and Stephen Parkinson, a former Home Office special adviser, was published in the August 23, 2020 issue of The Spectator. Trentmann laments that the problem lay in a combination of errors, omissions and distortions in the history section pages, which were also littered with mistakes.

Not only are historical distortions in textbooks a universal practice, but the many ways that this is done are equally universal and cut across competing ideologies. In Textbooks as Propaganda, the historian Joanna Wojdon demonstrates the methods that were used by the state in this respect in communist Poland (1944-1989).

The methods of distortions in this case were similar to the ones that were used in various former communist dictatorships such the Soviet Union and its satellite states in East Europe, and in China. The same methods in this context were also employed by totalitarian regimes in Nazi Germany, and in fascist Italy and Spain.

And if one examines the methods of distorting history textbooks, as examined by Loewen in the US and Trentmann in the UK, one can come across various similarities between how it is done in liberal democracies and how it was done in totalitarian set-ups.

I once shared this observation with an American academic in 2018. He somewhat agreed but argued that because of the Cold War (1945-1991) many democratic countries were pressed to adopt certain propaganda techniques that were originally devised by communist regimes. I tend to disagree. Because if this were a reason, then how is one to explain the publication of the book The Menace of Nationalism in Education by Jonathan French Scott in 1926 — almost 20 years before the start of the Cold War?

Scott meticulously examined history textbooks being taught in France, Germany, Britain and the US in the 1920s. It is fascinating to see how the methods used to write textbooks, described by Scott as tools of indoctrination, are quite similar to those applied in communist and fascist dictatorships, and how they are being employed in both developing as well as developed countries.

In a nutshell, no matter what ideological bent is being welded into textbooks in various countries, it has always been about altering history through engineered stories as a means of promoting particular agendas. This is done by concocting events that did not happen, altering those that did take place, or omitting events altogether.

It was Scott who most clearly understood this as a problem that is inherent in the whole idea of the nation state, which is largely constructed by clubbing people together as ‘nations’, not only within physical but also ideological boundaries.

This leaves nation states always feeling vulnerable and fearing that the glue that binds a nation together, through largely fabricated and manufactured ideas of ethnic, religious or racial homogeneity, will wear off. Thus the need is felt to keep it intact through continuous historical distortions.

Sunday, 6 January 2019

Saturday, 7 May 2016

Is it science or theology?

Pervez Hoodbhoy in The Dawn

When Pakistani students open a physics or biology textbook, it is sometimes unclear whether they are actually learning science or, instead, theology. The reason: every science textbook, published by a government-run textbook board in Pakistan, by law must contain in its first chapter how Allah made our world, as well as how Muslims and Pakistanis have created science.

I have no problem with either. But the first properly belongs to Islamic Studies, the second to Islamic or Pakistani history. Neither legitimately belongs to a textbook on a modern-day scientific subject. That’s because religion and science operate very differently and have widely different assumptions. Religion is based on belief and requires the existence of a hereafter, whereas science worries only about the here and now.

Demanding that science and faith be tied together has resulted in national bewilderment and mass intellectual enfeeblement. Millions of Pakistanis have studied science subjects in school and then gone on to study technical, science-based subjects in college and university. And yet most — including science teachers — would flunk if given even the simplest science quiz.

How did this come about? Let’s take a quick browse through a current 10th grade physics book. The introductory section has the customary holy verses. These are followed by a comical overview of the history of physics. Newton and Einstein — the two greatest names — are unmentioned. Instead there’s Ptolemy the Greek, Al-Kindi, Al-Beruni, Ibn-e-Haytham, A.Q. Khan, and — amusingly — the heretical Abdus Salam.

The end-of-chapter exercises test the mettle of students with such questions as: Mark true/false; A) The first revelation sent to the Holy Prophet (PBUH) was about the creation of Heaven? B) The pin-hole camera was invented by Ibn-e-Haytham? C) Al-Beruni declared that Sind was an underwater valley that gradually filled with sand? D) Islam teaches that only men must acquire knowledge?

Dear Reader: You may well gasp in disbelief, or just hold your head in despair. How could Pakistan’s collective intelligence and the quality of what we teach our children have sunk so low? To see more such questions, or to check my translation from Urdu into English, please visit the websitehttp://eacpe.org/ where relevant pages from the above text (as well as from those discussed below) have been scanned and posted.

Take another physics book — this one (English) is for sixth-grade students. It makes abundantly clear its discomfort with the modern understanding of our universe’s beginning. The theory of the Big Bang is attributed to “a priest, George Lamaitre [sic] of Belgium”. The authors cunningly mention his faith hoping to discredit his science. Continuing, they declare that “although the Big Bang Theory is widely accepted, it probably will never be proved”.

While Georges Lemaître was indeed a Catholic priest, he was so much more. A professor of physics, he worked out the expanding universe solution to Einstein’s equations. Lemaître insisted on separating science from religion; he had publicly chided Pope Pius XII when the pontiff grandly declared that Lemaître’s results provided a scientific validation to Catholicism.

Local biology books are even more schizophrenic and confusing than the physics ones. A 10th-grade book starts off its section on ‘Life and its Origins’ unctuously quoting one religious verse after another. None of these verses hint towards evolution, and many Muslims believe that evolution is counter-religious. Then, suddenly, a full page annotated chart hits you in the face. Stolen from some modern biology book written in some other part of the world, it depicts various living organisms evolving into apes and then into modern humans. Ouch!

Such incoherent babble confuses the nature of science — its history, purpose, method, and fundamental content. If the authors are confused, just imagine the impact on students who must learn this stuff. What weird ideas must inhabit their minds!

Compounding scientific ignorance is prejudice. Most students have been persuaded into believing that Muslims alone invented science. And that the heroes of Muslim science such as Ibn-e-Haytham, Al-Khwarizmi, Omar Khayyam, Ibn-e-Sina, etc owed their scientific discoveries to their strong religious beliefs. This is wrong.

Science is the cumulative effort of humankind with its earliest recorded origins in Babylon and Egypt about 6,000 years ago, thereafter moving to China and India, and then Greece. It was a millennium later that science reached the lands of Islam, where it flourished for 400 years before moving on to Europe. Omar Khayyam, a Muslim, was doubtless a brilliant mathematician. But so was Aryabhatta, a Hindu. What does their faith have to do with their science? Natural geniuses have existed everywhere and at all times.

Today’s massive infusion of religion into the teaching of science dates to the Ziaul Haq days. It was not just school textbooks that were hijacked. In the 1980s, as an applicant to a university teaching position in whichever department, the university’s selection committee would first check your faith.

In those days a favourite question at Quaid-e-Azam University (as probably elsewhere) was to have a candidate recite Dua-i-Qunoot, a rather difficult prayer. Another was to name each of the Holy Prophet’s wives, or be quizzed about the ideology of Pakistan. Deftly posed questions could expose the particularities of the candidate’s sect, personal degree of adherence, and whether he had been infected by liberal ideas.

Most applicants meekly submitted to the grilling. Of these many rose to become today’s chairmen, deans, and vice-chancellors. The bolder ones refused, saying that the questions asked were irrelevant. With strong degrees earned from good overseas universities, they did not have to submit to their bullying inquisitors. Decades later, they are part of a widely dispersed diaspora. Though lost to Pakistan, they have done very well for themselves.

Science has no need for Pakistan; in the rest of the world it roars ahead. But Pakistan needs science because it is the basis of a modern economy and it enables people to gain decent livelihoods. To get there, matters of faith will have to be cleanly separated from matters of science. This is how peoples around the world have managed to keep their beliefs intact and yet prosper. Pakistan can too, but only if it wants.

When Pakistani students open a physics or biology textbook, it is sometimes unclear whether they are actually learning science or, instead, theology. The reason: every science textbook, published by a government-run textbook board in Pakistan, by law must contain in its first chapter how Allah made our world, as well as how Muslims and Pakistanis have created science.

I have no problem with either. But the first properly belongs to Islamic Studies, the second to Islamic or Pakistani history. Neither legitimately belongs to a textbook on a modern-day scientific subject. That’s because religion and science operate very differently and have widely different assumptions. Religion is based on belief and requires the existence of a hereafter, whereas science worries only about the here and now.

Demanding that science and faith be tied together has resulted in national bewilderment and mass intellectual enfeeblement. Millions of Pakistanis have studied science subjects in school and then gone on to study technical, science-based subjects in college and university. And yet most — including science teachers — would flunk if given even the simplest science quiz.

How did this come about? Let’s take a quick browse through a current 10th grade physics book. The introductory section has the customary holy verses. These are followed by a comical overview of the history of physics. Newton and Einstein — the two greatest names — are unmentioned. Instead there’s Ptolemy the Greek, Al-Kindi, Al-Beruni, Ibn-e-Haytham, A.Q. Khan, and — amusingly — the heretical Abdus Salam.

The end-of-chapter exercises test the mettle of students with such questions as: Mark true/false; A) The first revelation sent to the Holy Prophet (PBUH) was about the creation of Heaven? B) The pin-hole camera was invented by Ibn-e-Haytham? C) Al-Beruni declared that Sind was an underwater valley that gradually filled with sand? D) Islam teaches that only men must acquire knowledge?

Dear Reader: You may well gasp in disbelief, or just hold your head in despair. How could Pakistan’s collective intelligence and the quality of what we teach our children have sunk so low? To see more such questions, or to check my translation from Urdu into English, please visit the websitehttp://eacpe.org/ where relevant pages from the above text (as well as from those discussed below) have been scanned and posted.

Take another physics book — this one (English) is for sixth-grade students. It makes abundantly clear its discomfort with the modern understanding of our universe’s beginning. The theory of the Big Bang is attributed to “a priest, George Lamaitre [sic] of Belgium”. The authors cunningly mention his faith hoping to discredit his science. Continuing, they declare that “although the Big Bang Theory is widely accepted, it probably will never be proved”.

While Georges Lemaître was indeed a Catholic priest, he was so much more. A professor of physics, he worked out the expanding universe solution to Einstein’s equations. Lemaître insisted on separating science from religion; he had publicly chided Pope Pius XII when the pontiff grandly declared that Lemaître’s results provided a scientific validation to Catholicism.

Local biology books are even more schizophrenic and confusing than the physics ones. A 10th-grade book starts off its section on ‘Life and its Origins’ unctuously quoting one religious verse after another. None of these verses hint towards evolution, and many Muslims believe that evolution is counter-religious. Then, suddenly, a full page annotated chart hits you in the face. Stolen from some modern biology book written in some other part of the world, it depicts various living organisms evolving into apes and then into modern humans. Ouch!

Such incoherent babble confuses the nature of science — its history, purpose, method, and fundamental content. If the authors are confused, just imagine the impact on students who must learn this stuff. What weird ideas must inhabit their minds!

Compounding scientific ignorance is prejudice. Most students have been persuaded into believing that Muslims alone invented science. And that the heroes of Muslim science such as Ibn-e-Haytham, Al-Khwarizmi, Omar Khayyam, Ibn-e-Sina, etc owed their scientific discoveries to their strong religious beliefs. This is wrong.

Science is the cumulative effort of humankind with its earliest recorded origins in Babylon and Egypt about 6,000 years ago, thereafter moving to China and India, and then Greece. It was a millennium later that science reached the lands of Islam, where it flourished for 400 years before moving on to Europe. Omar Khayyam, a Muslim, was doubtless a brilliant mathematician. But so was Aryabhatta, a Hindu. What does their faith have to do with their science? Natural geniuses have existed everywhere and at all times.

Today’s massive infusion of religion into the teaching of science dates to the Ziaul Haq days. It was not just school textbooks that were hijacked. In the 1980s, as an applicant to a university teaching position in whichever department, the university’s selection committee would first check your faith.

In those days a favourite question at Quaid-e-Azam University (as probably elsewhere) was to have a candidate recite Dua-i-Qunoot, a rather difficult prayer. Another was to name each of the Holy Prophet’s wives, or be quizzed about the ideology of Pakistan. Deftly posed questions could expose the particularities of the candidate’s sect, personal degree of adherence, and whether he had been infected by liberal ideas.

Most applicants meekly submitted to the grilling. Of these many rose to become today’s chairmen, deans, and vice-chancellors. The bolder ones refused, saying that the questions asked were irrelevant. With strong degrees earned from good overseas universities, they did not have to submit to their bullying inquisitors. Decades later, they are part of a widely dispersed diaspora. Though lost to Pakistan, they have done very well for themselves.

Science has no need for Pakistan; in the rest of the world it roars ahead. But Pakistan needs science because it is the basis of a modern economy and it enables people to gain decent livelihoods. To get there, matters of faith will have to be cleanly separated from matters of science. This is how peoples around the world have managed to keep their beliefs intact and yet prosper. Pakistan can too, but only if it wants.

Wednesday, 25 March 2015

Why Bank of England employees are reading my A-level economics textbook

Alain Anderton in The Guardian

A Freedom of Information request by the Times, showed that Economics, my A-level textbook and the “bible for those seeking a handle on basic economics”, was the most issued book from the library of the Bank of England. Since it was first published in 1991, the book has been the bestselling text in the A-level economics market. Generations of economists have learned their basic economics from studying it. However, it isn’t the economists at the Bank of England who are borrowing the book now. The bank has helpfully explained that it provides development for secretaries, graduates and school leavers. Panic over – the Bank of England is not being run by economists consulting a school textbook.

What is good about this news is that it means the Bank of England is serious about education and professional development. In Economics, you will find out that these are essential for the growth of the economy. They raise productivity levels of workers and contribute to our national wellbeing. Other topical points raised in the book include the fact that increasing the supply of oil on to world markets will lead to a fall in the price of oil; if you cut government spending, at least in the short term, aggregate demand will fall and so will GDP; that global warming is the result of market failure; and that directors and managers of companies might be more concerned with maximising their own benefits than the benefits of the shareholders of the company.

It is also good news that people want to find out about economics. Since the financial crisis of 2008, the numbers of people studying A-level economics have more than doubled, suggesting that these uncertain times have sparked the curiosity of 16- to 18-year-olds about the world in which they live.

Economics at A-level is fundamentally about studying models: ways of looking at the world and making sense of it. But it is also about evaluating the world around us. Was there an alternative for the UK to fiscal austerity in 2010? Does it matter that the UK persistently runs a current account deficit on the balance of payments? Should we regulate banks more? Would a significant rise in the minimum wage be good or bad and for whom? In A-level exams, only candidates who can show they understand basic economic models and appreciate that there are many sides to each issue will get top marks.

Should our politicians be studying some basic economics? The answer to that is obviously yes. What is particularly disheartening about much current political discourse is the failure of politicians to admit that there will be costs and disadvantages to their policies. Our adversarial system means that any such admission is seized upon by the media and blown up out of all proportion. The simple fact is that almost any economic decision has its costs and benefits.

The first concept an A-level student may well learn is the principle of opportunity cost. If you buy a car, you lose the benefits of what you could otherwise have bought with that money. If the government cuts taxes, what are the benefits that are going to be lost as a result of that decision, benefits like higher government spending or a lower national debt? However, to some extent we get the politicians we deserve. Too many people seem to think that there are simple answers to complex problems; we don’t want to pay for the choices we make. For example, we want high-quality public services but we don’t want to pay for them in taxes.

Our grasp of economics would be more mature if the acceptance of costs and benefits that are being acknowledged in classrooms were also being acknowledged at our dinner tables, in our local council chambers and in parliament.

A Freedom of Information request by the Times, showed that Economics, my A-level textbook and the “bible for those seeking a handle on basic economics”, was the most issued book from the library of the Bank of England. Since it was first published in 1991, the book has been the bestselling text in the A-level economics market. Generations of economists have learned their basic economics from studying it. However, it isn’t the economists at the Bank of England who are borrowing the book now. The bank has helpfully explained that it provides development for secretaries, graduates and school leavers. Panic over – the Bank of England is not being run by economists consulting a school textbook.

What is good about this news is that it means the Bank of England is serious about education and professional development. In Economics, you will find out that these are essential for the growth of the economy. They raise productivity levels of workers and contribute to our national wellbeing. Other topical points raised in the book include the fact that increasing the supply of oil on to world markets will lead to a fall in the price of oil; if you cut government spending, at least in the short term, aggregate demand will fall and so will GDP; that global warming is the result of market failure; and that directors and managers of companies might be more concerned with maximising their own benefits than the benefits of the shareholders of the company.

It is also good news that people want to find out about economics. Since the financial crisis of 2008, the numbers of people studying A-level economics have more than doubled, suggesting that these uncertain times have sparked the curiosity of 16- to 18-year-olds about the world in which they live.

Economics at A-level is fundamentally about studying models: ways of looking at the world and making sense of it. But it is also about evaluating the world around us. Was there an alternative for the UK to fiscal austerity in 2010? Does it matter that the UK persistently runs a current account deficit on the balance of payments? Should we regulate banks more? Would a significant rise in the minimum wage be good or bad and for whom? In A-level exams, only candidates who can show they understand basic economic models and appreciate that there are many sides to each issue will get top marks.

Should our politicians be studying some basic economics? The answer to that is obviously yes. What is particularly disheartening about much current political discourse is the failure of politicians to admit that there will be costs and disadvantages to their policies. Our adversarial system means that any such admission is seized upon by the media and blown up out of all proportion. The simple fact is that almost any economic decision has its costs and benefits.

The first concept an A-level student may well learn is the principle of opportunity cost. If you buy a car, you lose the benefits of what you could otherwise have bought with that money. If the government cuts taxes, what are the benefits that are going to be lost as a result of that decision, benefits like higher government spending or a lower national debt? However, to some extent we get the politicians we deserve. Too many people seem to think that there are simple answers to complex problems; we don’t want to pay for the choices we make. For example, we want high-quality public services but we don’t want to pay for them in taxes.

Our grasp of economics would be more mature if the acceptance of costs and benefits that are being acknowledged in classrooms were also being acknowledged at our dinner tables, in our local council chambers and in parliament.

Monday, 11 November 2013

Economics lecturers accused of clinging to pre-crash fallacies

Academic says courses changed little since 2008 and students taught 'theories now known to be untrue'

- Phillip Inman, economics correspondent

- The Guardian,

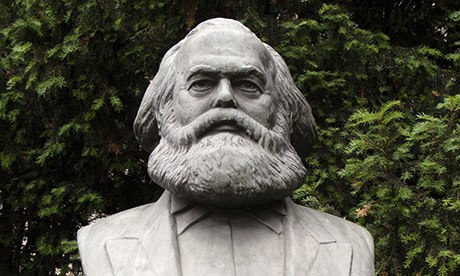

Economics departments have been accused of ignoring critics of the free market such as Karl Marx. Photograph: Alamy

Economics teaching at Britain's universities has come under fire from a leading academic who accused lecturers of presenting "things that are known to be untrue" to preserve theories that claim to show how the economy works.

The Treasury is hosting a conference in London on Monday to discuss the crisis in economics teaching, which critics say has remained largely unchanged since the 2008 financial crash despite the failure of many in the profession to spot the looming credit crunch and worst recession for 100 years.

Michael Joffe, professor of economics at Imperial College, London, said he was disturbed by the way economics textbooks continued to discuss concepts and models as facts when they were debunked decades ago.

He said: "What if economics was based more on empirical studies and empirical evidence? There are lots of studies and economists are often very good at finding the evidence for how things work, but it does not feed into or challenge what's in the textbooks.

"I asked a textbook author recently why a theory that is known to be wrong is still appearing in his book he said to me that his publisher would expect it to be there."

Joffe, a former biologist, called for more evidence in economic teaching in the October edition of the Royal Economic Society newsletter. He said many reformers had called for economics courses to embrace the teachings of Marx and Keynes to undermine the dominance of neoclassical free-market theories, but the aim should be to provide students with analysis based on the way the world works, not the way theories argue it ought to work.

"There is a lot that is taught on economics courses that bears little relation to the way things work in the real world," he said.

The Treasury-hosted conference will debate the state of economics teaching, with leading figures from the profession invited to speak, including Bank of England director Andy Haldane. Sponsored by the Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET), it aims to highlight reforms to address the shortcomings of the core economics curriculum.

Headed by economics professor Eric Beinhocker of Oxford University, the INET has grown into a large international lobby group with the aim of reforming mainstream economic teaching in the world's leading colleges.

The conference comes only a fortnight after Manchester University economics students criticised orthodox free-market teaching on their course, arguing that alternative ways of thinking have been pushed to the margins.

Members of the Post-Crash Economics Society said their course was dominated by models and equations that trained undergraduates for City jobs without a broader understanding of the way economies and businesses work.

Joe Earle, a spokesman for the society and a final-year undergraduate, said academic departments were ignoring the crisis in the profession and that, by neglecting global developments and critics of the free market such as Keynes and Marx, the study of economics was "in danger of losing its broader relevance".

The profession has been criticised for its adherence to models of a free market that claim to show demand and supply continually rebalancing over relatively short periods of time – in contrast to the decade-long mismatches that came ahead of the banking crash in key markets such as housing and exotic derivatives, where asset bubbles ballooned.

Joffe said university economics department were continuing to teach concepts that had been disproved. In one example he said the idea that companies suffer "dis-economies of scale" when they increase production beyond certain capacity was true in only a small number of firms.

The U-shaped curve shows that unit costs are high when production begins and become cheaper as economies of scale allow a company to spread costs over more units. Units become more expensive to produce after a factory reaches capacity.

Joffe said: "We ought to stop teaching the U shape as the typical relationship between costs and scale, for the simple reason that it is false."

Sunday, 20 October 2013

Ethics, Economics, Education

The decision of the courts against a photocopying shop that provided course-material to Delhi University students will have global repercussions

ALI KHAN MAHMUDABAD in outlook India

The right to education is fundamental to the development of any society. Implicit within this right is the right to access knowledge without being constrained by one's socio-economic background. The state, which is the mediator between private interest and public good, has a duty to enforce these rights. A court case in India instituted last year by Taylor and Francis, Cambridge University Press and its Oxford equivalent against Delhi University and Rameshwari Photocopy Services is being heard again and will force the judicial system not only to address technical and legal questions concerning copyright but deeper questions about what constitutes the public good.

The case concerns the photocopying and sale of books printed by these publishing houses, as buying the originals, even the Indian editions, is beyond the means of most students. In fact, has been established through empirical studies by academics like Shamshad Basheer, often only short sections of these books are copied to make course-packs as is done in the US under the 'fair use' laws. A bare reading of the copyright laws in India might lead some to the conclusion that the photocopying is illegal as the photocopying house, an official licensee of Delhi University, is making a profit. At the same time the carefully worded section 52 of the Indian copyright act makes certain provisions, as has been argued by Niraj Kishan Kaul the advocate for the University of Delhi and goes to great lengths to differentiate between ‘reproduction of work’ and ‘issuing copies of work’ and sub-clauses that allow for an exception to be made for students and teachers.

The court granted temporary relief to the petitioners and stopped the photostat shop from making any copies and on the last hearing on the 1st of October listed the matter for the 21st of October.

Interestingly, copyright laws have not always been restrictive. In 1790 a copyright law was passed in America, actually permitting the re-printing of foreign material, as copyright was deemed a privilege and not a right, which led to an entire industry being built around material that otherwise might have been deemed ‘pirated.’ So although today America is a stickler for enforcing copyright laws, its own market was initially built by breaking these very rules.

What is perhaps of as great importance as a discussion of the technical aspects of the law is a conversation about the value of the service being provided by the Rameshwari Photocopying Services and, crucially, what the stance of the university presses says about their approach to knowledge dissemination.

The argument that the authors of academic works suffer is largely redundant as most academic presses give relatively modest remuneration to the writers. Furthermore, many of the people mentioned in the lawsuit, including noted academics such as Amartya Sen amongst others, have actually written an open letter opposing the case. Notably, there are very few countries in the world in which academics are remunerated in a manner which is commensurate with the role they play in today’s world: writing the history of the future of coming generations. Most academics do what they do because of a love of the subject and of course there are those who are able to cash in on their expertise but these form the exception rather than the norm. The argument for a loss of income to the publishing house is also questionable since the closing down of shops such as the Rameshwari Services will not mean that the students will suddenly be able to buy original prints as these will still be too expensive.

In a section entitled ‘what we do’ the Cambridge University Press website states in big bold letters that its purpose is “to further the University’s objective of advancing learning, knowledge and research.’ Beneath this admirably expressed goal, in smaller font, the blurb talks of 'the global market place,’ ‘their 50 global offices’ and ‘the distribution of their products.’ The two parts of the section speak volumes about the press’ approach in fulfilling its objectives and indeed this is symptomatic of a system that encourages institutions or indeed individuals to profess an ethical approach to economics but one which is in actual fact often under girded by a fine print that almost inevitably puts self-interest before anything else. The Oxford University Press website states similar aims and interestingly even acknowledges that "access to research helps push the boundaries of research."

Of course any institution needs to be self-sufficient but at the same time in many countries those institutions that are deemed to be serving a public good are granted tax-free charitable status, as is the case with both the university presses. This of course in effect means that the taxpayer subsidizes them.

The case instituted by these publishing houses then seems to be part of the worrying effort to commercialize education by making it bend to the ‘logic’ of the market. India is already facing the effects of unregulated private educational institutions that are often used to launder money and which essentially offer a degree on payment service. The publishing houses then are acting in a manner which is no different from the way in which certain corporate entities bully smaller organisations out of the market. The difference is that the some of the students who buy photocopied material might well end up publishing material with the university presses because ultimately both are part of the same system. In a recent statement the spokesperson for the Cambridge Press even said that their primary purpose is "not as a commercial organisation."

In a speech in the House of Commons on the 5th of February 1841 Lord Macaulay, while accepting its necessity, dubbed copyright ‘a tax on readers for the purpose of giving a bounty to writers…for one of the most salutary and innocent of human pleasures.’ Later in the speech, he gave the example of Milton’s poetry, the sole copyright of which lay with a bookseller called Tonson who once took a rival to court for publishing a cheap version of Paradise Lost, after its performance at the Garrick theatre. Macaulay then concluded that the effects of this monopoly led to a situation where ‘the reader is pillaged; and the writer’s family is not enriched.’

The decision of the Indian courts will have global repercussions, as has been the case in its rulings against big pharmaceutical companies. The practice of making course-books is found in many other countries such as Nigeria, Peru and Iran, with the latter also suffering as sanctions mean that many journals cannot be accessed, let alone copied. In Syria, just outside the University of Damascus, in the underpass beneath the Mezze autostradde were a number of shops that provided cheap copies to students who otherwise would not have had access to key material.

In a world delineated by bottom lines, fine prints and sub-clauses, in which freedom in essence translates into 'consumerist freedom,' it is easy to speak of ideals and values but much harder to put them into action. As Harvard philosopher Michael Sandel argues, the more we treat everything as a product to be sold or bought, including our education, our bodies and even our emotions, the more we devalue their intrinsic worth and so what is needed is 'bringing ethics, morality and virtue into public discourse.' For students, any society's real assets, the closure of the small yet crucial services provided by shops that produce photocopied coursework would only add one more obstacle in a country that is already riven with economic disparities.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.png)