'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label corporations. Show all posts

Showing posts with label corporations. Show all posts

Wednesday, 31 July 2024

Wednesday, 8 October 2014

Our bullying corporations are the new enemy within

The demands of business dominate our politicians and embed inequality. It’s a full-blown assault on democracy

The more power you possess, the more insecure you feel. The paranoia of power drives people towards absolutism. But it doesn’t work. Far from curing them of the conviction that they are threatened and beleaguered, greater control breeds greater paranoia.

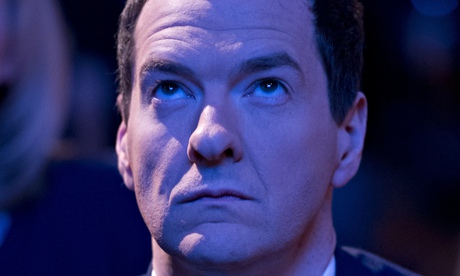

On Friday, the chancellor of the exchequer, George Osborne, claimed that business is under political attack on a scale it has not faced since the fall of the Berlin Wall. He was speaking at the Institute of Directors, where he was introduced with the claim that “we are in a generational struggle to defend the principles of the free market against people who want to undermine it or strip it away”. A few days before, while introducing Osborne at the Conservative party conference, Digby Jones, former head of the Confederation of British Industry, warned that companies are at risk of being killed by “regulation from ‘big government’” and of drowning “in the mire of anti-business mood music encouraged by vote-seekers”. Where is that government and who are these vote-seekers? They are a figment of his imagination.

Where, with the exception of the Greens and Plaid Cymru – who have four MPs between them – are the political parties calling for greater restraints on corporate power? When David Cameron boasts that he is “rolling out the red carpet” for multinational corporations, “cutting their red tape, cutting their taxes”, promising always to set “the most competitive corporate taxes in the G20: lower than Germany, lower than Japan, lower than the United States”, all Labour can say is “us too”.

Its shadow business secretary, Chuka Umunna, once a fierce campaigner against tax avoidance, accepted a donation by a company which delivers “tailored tax solutions to individuals and organisations internationally”. The shadow chancellor, Ed Balls, cannot open his lips without clamping them around the big business boot. There’s no better illustration of the cross-party corporate consensus than the platform the Tories gave to Jones to voice his paranoia. Jones was ennobled by Tony Blair and appointed as a minister in the Labour government. Now he rolls up at the Conservative conference to applaud Osborne as the man who “did what was right for our country. A personal pat on the back for that.” A pat on the head would have been more appropriate – you can see which way power flows.

The corporate consensus is enforced not only by the lack of political choice, but by an assault on democracy itself. Steered by business lobbyists, the EU and the US are negotiating a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. This would suppress the ability of governments to put public interest ahead of profit. It could expose Britain to cases like El Salvador’s, where an Australian company is suing the government before a closed tribunal of corporate lawyers for $300m (nearly half the country’s annual budget) in potential profits foregone. Why? Because El Salvador refused permission for a gold mine that would poison people’s drinking water.

Last month the Commons public accounts committee found that the British government has inserted a remarkable clause into contracts with the companies to whom it is handing the probation service (one of the maddest privatisations of all). If a future government seeks to cancel these contracts (Labour has said it will) it would have to pay the companies the money they would otherwise have made over the next 10 years. Yes, 10 years. The penalty would amount to between £300m and £400m.

Windfalls like this are everywhere: think of the billion pounds the government threw into the air when it sold Royal Mail, or the massive state subsidies quietly being channelled to the private train companies. When Cameron told the Conservative party conference “there’s no reward without effort; no wealth without work; no success without sacrifice”, he was talking cobblers. Thanks to his policies, shareholders and corporate executives become stupendously rich by sitting in the current with their mouths open.

Ours is a toll-booth economy, unchallenged by any major party, in which companies which have captured essential public services – water, energy, trains – charge extraordinary fees we have no choice but to pay. If there is a “generational struggle to defend the principles of the free market”, it’s a struggle against the corporations, which have replaced the market with a state-endorsed oligarchy.

It’s because of the power of corporations that the minimum wage remains so low, while executives cream off millions. It’s because of this power that most people in poverty are in work, and the state must pay billions to supplement their appalling wages. It’s because of this power that, in the midst of a crisis so severe that the world has lost over 50% of its vertebrate wildlife in just 40 years, the government is organising a bonfire of environmental protection. It’s because of this power that instead of innovative taxation (such as a financial transactions tax and land value taxation) we have permanent austerity for the poor. It’s because of this power that billions are still pumped into tax havens. It’s because of this power that Britain is becoming a tax haven in its own right.

And still they want more. Through a lobbying industry and a political funding system, successive governments have failed to reform, corporations select and buy and bully the political class to prevent effective challenge to their hegemony. Any politician brave enough to stand up to them is relentlessly hounded by the corporate media. Corporations are the enemy within.

So it’s depressing to see charities falling over themselves to assure Osborne that they are not, as he alleged last week, putting the counter view to the “business argument”.“We don’t recognise the divide he draws between the concerns of businesses and charities,” says Oxfam. People “should be celebrating not denigrating the relationship between business and charities”, says the National Council for Voluntary Organisations. These are good groups, doing good work. But if, in the face of a full-spectrum assault by corporate power on everything they exist to defend, they cannot stand up and name the problem, you have to wonder what they are for.

There’s a generational struggle taking place all right: a struggle over what remains of our democracy. It’s time we joined it.

Monday, 7 April 2014

Arundhati Roy explains how corporations run India and why they want Narendra Modi as prime minister

by Charlie Smith on Mar 30, 2014 at 1:51 pm

Indian author Arundhati Roy wants the world to know that her country is under the control of its largest corporations.

"Wealth has been concentrated in fewer and fewer hands," Roy tells the Georgia Straight by phone from New York. "And these few corporations now run the country and, in some ways, run the political parties. They run the media."

The Delhi-based novelist and nonfiction writer argues that this is having devastating consequences for hundreds of millions of the poorest people in India, not to mention the middle class.

Roy spoke to the Straight in advance of a public lecture on Tuesday (April 1) at 8 p.m. at St. Andrew's–Wesley United Church at the corner of Burrard and Nelson streets. She says it will be her first visit to Vancouver.

In recent years, she has researched how the richest Indian corporations—such as Reliance, Tata, Essar, and Infosys—are employing similar tactics as those of the U.S.-based Rockefeller and Ford foundations.

She points out that the Rockefeller and Ford foundations have worked closely in the past with the State Department and Central Intelligence Agency to further U.S. government and corporate objectives.

Now, she maintains that Indian companies are distributing money through charitable foundations as a means of controlling the public agenda through what she calls "perception management".

She acknowledges that the Tata Group has been doing this for decades, but says that more recently, other large corporations have begun copying this approach.

Private money replaces public funding

According to her, the overall objective is to blunt criticism of neoliberal policies that promote inequality.

"Slowly, they decide the curriculum," Roy maintains. "They control the public imagination. As public money gets pulled out of health care and education and all of this, NGOs funded by these major financial corporations and other kinds of financial instruments move in, doing the work that missionaries used to do during colonialism—giving the impression of being charitable organizations, but actually preparing the world for the free markets of corporate capital."

She was awarded the Booker Prize in 1997 for The God of Small Things. Since then, she has gone on to become one of India's leading social critics, railing against mining and power projects that displace the poor.

She's also written about poverty-stricken villagers in the Naxalite movement who are taking up arms across several Indian states to defend their traditional way of life.

"I'm a great admirer of the wisdom and the courage that people in the resistance movement show," she says. "And they are where my own understanding comes from."

One of her greatest concerns is how foundation-funded NGOs "defuse people's movements and...vacuum political anger and send them down a blind alley".

"It's very important to keep the oppressed divided," she says. "That's the whole colonial game, and it's very easy in India because of the diversity."

Roy writes a book on capitalism

In 2010, there was an attempt to lay a charge of sedition against her after she suggested that Kashmir is not integral to India's existence. This northern state has been at the centre of a long-running territorial dispute between India and Pakistan.

"There's supposed to be some police inquiry, which hasn't really happened," Roy tells the Straight. "That's how it is in India. They...hope that the idea of it hanging over your head is going to work its magic, and you're going to be more cautious."

Clearly, it's had little effect in silencing her. In her upcoming new book Capitalism: A Ghost Story, Roy explores how the 100 richest people in India ended up controlling a quarter of the country's gross-domestic product.

The book is inspired by a lengthy 2012 article with the same title, which appeared in India's Outlook magazine.

In the essay, she wrote that the "ghosts" are the 250,000 debt-ridden farmers who've committed suicide, as well as "800 million who have been impoverished and dispossessed to make way for us". Many live on less than 40 Canadian cents per day.

"In India, the 300 million of us who belong to the post-IMF 'reforms' middle class—the market—live side by side with spirits of the nether world, the poltergeists of dead rivers, dry wells, bald mountains and denuded forests," Roy wrote.

The essay examined how foundations rein in Indian feminist organizations, nourish right-wing think tanks, and co-opt scholars from the community of Dalits, often referred to in the West as the "untouchables".

For example, she pointed out that the Reliance Group's Observer Research Foundation has a stated goal of achieving consensus in favour of economic reforms.

Roy noted that the ORF promotes "strategies to counter nuclear, biological and chemical threats". She also revealed that the ORF's partners include weapons makers Raytheon and Lockheed Martin.

Anna Hazare called a corporate mascot

In her interview with the Straight, Roy claims that the high-profile India Against Corruption campaign is another example of corporate meddling.

According to Roy, the movement's leader, Anna Hazare, serves as a front for international capital to gain greater access to India's resources by clearing away any local obstacles.

With his white cap and traditional white Indian attire, Hazare has received global acclaim by acting as a modern-day Mahatma Gandhi, but Roy characterizes both of them as "deeply disturbing". She also describes Hazare as a "sort of mascot" to his corporate backers.

In her view, "transparency" and "rule of law" are code words for allowing corporations to supplant "local crony capital". This can be accomplished by passing laws that advance corporate interests.

She says it's not surprising that the most influential Indian capitalists would want to shift public attention to political corruption just as average Indians were beginning to panic over the slowing Indian economy. In fact, Roy adds, this panic turned into rage as the middle class began to realize that "galloping economic growth has frozen".

"For the first time, the middle classes were looking at corporations and realizing that they were a source of incredible corruption, whereas earlier, there was this adoration of them," she says. "Just then, the India Against Corruption movement started. And the spotlight turned right back onto the favourite punching bag—the politicians—and the corporations and the corporate media and everyone else jumped onto this, and gave them 24-hour coverage."

Her essay in Outlook pointed out that Hazare's high-profile allies, Arvind Kerjiwal and Kiran Bedi, both operate NGOs funded by U.S. foundations.

"Unlike the Occupy Wall Street movement in the US, the Hazare movement did not breathe a word against privatisation, corporate power or economic 'reforms'," she wrote in Outlook.

Narendra Modi seen as right-wing saviour

Meanwhile, Roy tells the Straight that corporate India is backing Narendra Modi as the country's next prime minister because the ruling Congress party hasn't been sufficiently ruthless against the growing resistance movement.

"I think the coming elections are all about who is going to crank up the military assault on troublesome people," she predicts.

In several states, armed rebels have prevented massive mining and infrastructure projects that would have displaced massive numbers of people.

Many of these industrial developments were the subject of memoranda of understanding signed in 2004.

Modi, head of the Hindu nationalist BJP coalition, became infamous in 2002 when Muslims were massacred in the Indian state of Gujarat, where he was the chief minister. The official death tollexceeded 1,000, though some say the figures are higher.

Police reportedly stood by as Hindu mobs went on a killing spree. Many years later, a senior police officer alleged that Modi deliberately allowed the slaughter, though Modi has repeatedly denied this.

The atrocities were so appalling that the American government refused to grant Modi a visitor's visa to travel to the United States.

But now, he's a political darling to many in the Indian elite, according to Roy. A Wall Street Journal report recently noted that the United States is prepared to give Modi a visa if he becomes prime minister.

"The corporations are all backing Modi because they think that [Prime Minister] Manmohan [Singh] and the Congress government hasn't shown the nerve it requires to actually send in the army into places like Chhattisgarh and Orissa," she says.

She also labels Modi as a politician who's capable of "mutating", depending on the circumstances.

"From being this openly sort of communal hatred-spewing saccharine person, he then put on the suit of a corporate man, and, you know, is now trying to play the role of the statesmen, which he's not managing to do really," Roy says.

Roy sees parallels between Congress and BJP

India's national politics are dominated by two parties, the Congress and the BJP.

The Congress maintains a more secular stance and is often favoured by those who want more accommodation for minorities, be they Muslim, Sikh, or Christian. In American terms, the Congress is the equivalent of the Democratic Party.

The BJP is actually a coalition of right-wing parties and more forcefully advances the notion that India is a Hindu nation. It often calls for a harder line against Pakistan. In this regard, the BJP could be seen as the Republicans of India.

But just as left-wing U.S. critics such as Ralph Nader and Noam Chomsky see little difference between the Democrats and Republicans in office, Roy says there is not a great deal distinguishing the Congress from the BJP.

"I've said quite often, the Congress has done by night what the BJP does by day," she declares. "There isn't any real difference in their economic policy."

Whereas senior BJP leaders encouraged wholesale mob violence against Muslims in Gujarat, she notes that Congress leaders played a similar role in attacks on Sikhs in Delhi following the 1984 assassination of then–prime minister Indira Gandhi.

"It was genocidal violence and even today, nobody has been punished," Roy says.

As a result, each party can accuse the other of fomenting communal violence.

In the meantime, there are no serious efforts at reconciliation for the victims.

"The guilty should be punished," she adds. "Everyone knows who they are, but that will not happen. That is the thing about India. You may go to prison for assaulting a woman in a lift or killing one person, but if you are part of a massacre, then the chances of your not being punished are very high."

However, she acknowledges that there is "some difference" in the two major parties' stated idea of India.

The BJP, for example, is "quite open about its belief in the Hindu India...where everybody else lives as, you know, second-class citizens".

"Hindu is also a very big and baggy word," she says to clarify her remark. "We're really talking about an upper-caste Hindu nation. And the Congress states that it has a secular vision, but in the actual playing out of how democracy works, all of them are involved with creating vote banks, setting community against community. Obviously, the BJP is more vicious at that game."

Inequality linked to caste system

The Straight asks why internationally renowned authors such as Salman Rushdie and Vikram Seth or major Indian film stars like Shahrukh Khan or the Bachchan family don't speak forcefully against the level of inequality in India.

"Well, I think we're a country whose elite is capable of an immense amount of self-deception and an immense amount of self-regard," she replies.

Roy maintains that Hinduism's caste system has ingrained the Indian elite to accept the idea of inequality "as some kind of divinely sanctioned thing".

According to her, the rich believe "that people who are from the lower classes don't deserve what those from the upper classes deserve".

Her comments on corporate power echo some of the ideas of Canadian activist and author Naomi Klein.

"Of course, I know Naomi very well," Roy reveals. "I think she's such a fine thinker and of course, she's influenced me."

Roy also expresses admiration for the work of Indian journalist Palagummi Sainath, author of the 1992 classic Everybody Loves a Good Drought: Stories from India's Poorest Districts.

However, she suggests that the concentration of media ownership in India makes it very difficult for most reporters to reveal the extent of corporate control over society.

"In India, if you're a really good journalist, your life is in jeopardy because there is no place for you in a media that's structured like that," Roy says.

On occasions, mobs have shown up outside her home after she's made controversial

statements in the media.

She says that in those instances, they seemed more interested in performing for the television cameras than in attacking her.

However, she emphasizes that other human-rights activists in India have had their offices trashed by demonstrators, and some have been beaten up or killed for speaking out against injustice.

Roy adds that thousands of political prisoners are locked up in Indian jails for sedition or for violating the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act.

This is one reason why she argues that it's a fallacy to believe that because India holds regular elections, it's a democratic country.

"There isn't a single institution anymore which an ordinary person can approach for justice: not the judiciary, not the local political representative," Roy maintains. "All the institutions have been hollowed out and just the shell has been put back. So democracy and these festivals of elections is when everyone can let off steam and feel that they have some say over their lives."

In the end, she says it's the corporations that fund major parties, which end up doing their bidding.

"We are really owned and run by a few corporations, who can shut India down when they want," Roy says.

Wednesday, 31 October 2012

A roll call of corporate rogues who are milking the country

Police officers

protect a Starbucks outlet in Oxford Street during the TUC

anti-austerity protest in London on 20 October 2012. Photograph: Suzanne

Plunkett/Reuters

Those at the sharp end are being hit hardest: from cuts to disability and housing benefits, tax credits and the educational maintenance allowance and now increases in council tax while NHS waiting lists are lengthening, food banks are mushrooming across the country and charities report sharp increases in the number of children going hungry. All this to pay for the collapse in corporate investment and tax revenues triggered by the greatest crash since the 30s.

At the other end of the spectrum though, things are going swimmingly. The richest 1,000 people in Britain have seen their wealth increase by £155bn since the crisis began – more than enough to pay off the whole government deficit of £119bn at a stroke. Anyone earning over £1m a year can look forward to a £42,000 tax cut in the spring, while firms have been rewarded with a 2% cut in corporation tax to 24%.

Not that many of them pay anything like that, even now. The scale of tax avoidance by high-street brand multinationals has now become clear, in no small part thanks to campaigning groups such as UK Uncut. Asda, Google, Apple, eBay, Ikea, Starbucks, Vodafone: all pay minimal tax on massive UK revenues, mostly by diverting profits earned in Britain to their parent companies, or lower tax jurisdictions via royalty and service payments or transfer pricing.

Four US companies – Amazon, Facebook, Google and Starbucks – have paid just £30m tax on sales of £3.1bn over the last four years, according to a Guardian analysis. Apple is estimated to have avoided over £550m in tax on more than £2bn worth of sales in Britain by channelling business through Ireland, while Starbucks has paid no corporation tax in Britain for the last three years.

The Tory MP and tax lawyer Charlie Elphicke estimates 19 US-owned multinationals are paying an effective tax rate of 3% on British profits, instead of the standard rate of 26%. It's all entirely legal, of course. But taken together with the multiple individual tax scams of the elite, this roll call of corporate infamy has become an intolerable scandal, when taxes are rising and jobs, benefits and pay being cut for the majority.

Not only that, but collecting the taxes that these companies have wriggled out of would go a long way to shrinking the deficit for which working- and middle-class Britain's living standards are being sacrificed. The total tax gap between what's owed and collected has been estimated by Richard Murphy of Tax Research UK at £120bn a year: £25bn in legal tax avoidance, £70bn in fraudulent tax evasion and £25bn in late payments.

Revenue and Customs' own last guess of £35bn has been widely recognised as a serious underestimate. But even allowing for the fact that it would never be possible to close the entire gap, those figures give a sense of what resources could be mobilised with a determined crackdown. Set them, for instance, against the £83bn in cuts planned for this parliament (including £18bn in welfare) – or the £1.2bn estimated annual benefit fraud bill – and you get a sense of what's at stake.

Cameron and Osborne wring their hands at the "moral repugnance" of "aggressive avoidance", but are doing nothing serious about it whatever. They've been toying with a general "anti-abuse" principle. But it would only catch a handful of the kind of personal dodges the comedian Jimmy Carr signed up to, not the massive profit-shuffling corporate giants have been dining off.

Meanwhile, ministers are absurdly slashing the tax inspection workforce, and even introducing a new incentive for British multinationals to move their operations inbusiness to overseas tax havens. The scheme would, accountants KPMG have been advising clients, offer an "effective UK tax rate of 5.5%" from 2014 (and cut British tax revenues into the bargain).

It's not as if there aren't any number of measures that would plug the loopholes and slash tax avoidance and evasion. They include a general anti-avoidance principle (of the kind the Labour MP Michael Meacher has been pushing in a private member's bill) that would outlaw any transaction whose primary purpose was avoidance rather than economic; minimum tax (backed even by the Conservative Elphicke); and country-by-country financial reporting, and unitary taxation, to expose transfer pricing and limit profit-siphoning.

The latter would work better with international agreement. But there is already majority support in the European Union, and it is governments in countries such as Britain – where the City is itself a tax haven – that are resisting reform. When you realise how closely the tax avoidance industry is tied up with government and drawing up tax law, that's perhaps not so surprising.

But when austerity and cuts are sucking demand out of the economy, fuelling poverty and joblessness and actually widening the deficit, the need to step up the pressure for corporations and the wealthy to pay their share as part of a wider recovery strategy couldn't be more obvious.

The target has to shift from "welfare scroungers" to tax dodgers, and the campaign go national. Companies that are milking the country at the expense of the majority are especially vulnerable to brand damage. Forcing them to pay up is a matter of both social justice and economic necessity.

Tuesday, 8 May 2012

Extend Freedom of Information to the Private Sector

Freedom of information: my monstrous idea will keep corporate tyrants at bay

Extending transparency laws to the private sector would make the likes of News International think twice before misbehaving

Illustration by Daniel Pudles

There are several means by which they do so: the privatisation and outsourcing of public services; the stuffing of public committees with corporate executives; and the reshaping of laws and regulations to favour big business. In the UK, the Health and Social Care Act extends the corporate domain in ways unimaginable even five years ago.

With these increasing powers come diminishing obligations. Through repeated cycles of deregulation, governments release big business from its duty of care towards both people and the planet. While citizens are subject to ever more control – as the state extends surveillance and restricts our freedom to protest and assemble – companies are subject to ever less.

In this column I will make a proposal that sounds – at first – monstrous, but I hope to persuade you is both reasonable and necessary: that freedom of information laws should be extended to the private sector.

The very idea of a corporation is made possible only by a blurring of the distinction between private and public. Limited liability socialises risks that would otherwise be carried by a company's owners and directors, exempting them from the costs of the debts they incur or the disasters they cause. The bailouts introduced us to an extreme form of this exemption: men like Fred Goodwin and Matt Ridley are left in peace to count their money while everyone else must pay for their mistakes.

So I am asking only for the exercise of that long-standing Conservative maxim – no rights without responsibilities. If you benefit from limited liability, the public should be permitted to scrutinise your business.

Companies already have certain obligations towards transparency, such as the publication of financial statements and annual reports. But these tell us only a little of what we need to know. In News International's annual report, you will find none of the information disclosed at the Leveson inquiry, though it is of pressing public interest. In fact it is only due to a combination of the Guardian's persistence and pure chance (the discovery that Milly Dowler's phone had been hacked) that we know anything about the wide-ranging assault on democracy engineered by that company.

Privatisation and outsourcing ensure that private business is, or should be, everyone's business. Private companies now provide services we are in no position to refuse, yet, unlike the state bodies they replace, they are not subject to the Freedom of Information Act. The results can be catastrophic for public accounts.

Just as the Blair government did while imposing the disastrous private finance initiative, the Bullingdon boys now shield their schemes from public scrutiny behind the corporate information wall. Companies are once again striking remarkable deals, hatched in secret, at the expense of taxpayers, pupils and patients. Last week, for example, we learned that Circle Healthcare will be able to extract millions of pounds a year from a public hospital, Hinchingbrooke, which is in deep financial trouble. Crucial information about the deal remains secret on the grounds of Circle's "commercial confidentiality".

The principle of corporate transparency is already established in English law. The Freedom of Information Act has a clause enabling the government to extend it to companies with public contracts. Unsurprisingly, it has not been exercised. The environmental information rules of 2004 define a public authority as any body providing public services, which includes corporations. Why should this not apply universally?

The Campaign for Freedom of Information points out that the Scottish government almost adopted this idea: it proposed extending the transparency laws to major government contractors. But though this plan was overwhelmingly popular, it was dropped last year on the grounds that the contractors were opposed to it. (Who would have guessed?) South Africa, by contrast, provides a general right of access to the records of private bodies. The ANC, aware of how corporations assisted apartheid, recognises that the state is not the only threat to democracy.

Freedom of information is never absolute, nor should it be. Companies should retain the right, as they do in South Africa, to protect material that is of genuine commercial confidentiality; though they should not be allowed to use that as an excuse to withhold everything that might embarrass them. The information commissioner should decide where the line falls, just as he does for public bodies today.

The purpose of this monstrous proposal is not just to shine a light into the rattling cupboards of private companies, but to change the way in which they behave. A body that acts as if the world is watching presents less of a threat to the public interest than a body that knows it won't get caught. Would News International have acted as it did if its emails could have been revealed as a matter of course rather than a matter of chance? If it is true that "governments don't rule the world, Goldman Sachs rules the world", should we not be entitled to know what Goldman Sachs is up to? Is that not the only means we have of preventing its unelected power from becoming tyrannical?

I realise that it is not a good time to be making this request: far from extending our transparency laws, Cameron hints that he wants to roll them back. But unless we decide what we want and how we mean to obtain it – however remote it might now seem – we have no means of making social progress. If we are to reclaim power from the corporations that have seized it, first we need to know what that power looks like.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)