'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label mortality. Show all posts

Showing posts with label mortality. Show all posts

Friday, 5 January 2024

Sunday, 2 May 2021

Tuesday, 19 March 2019

The best form of self-help is … a healthy dose of unhappiness

We’re seeking solace in greater numbers than ever. But we’re more likely to find it in reality than in positive thinking writes Tim Lott in The Guardian

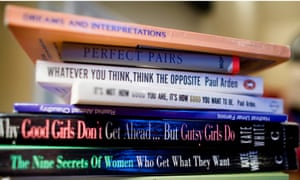

‘Self-help is almost as broad a genre as fiction.’ Photograph: Christopher Thomond/The Guardian

Booksellers have announced that sales of self-help books are at record levels. The cynics out there will sigh deeply in resignation, even though I suspect they don’t really have a clear idea of what a self-help book is (or could be). Then again, no one has much of an idea what a self-help book is. Is it popular psychology (such as Blink, or Daring Greatly)? Is it spirituality (The Power of Now, or A Course in Miracles)? Or a combination of both (The Road Less Travelled)?

Is it about “success” (The Seven Secrets of Successful People) or accumulating money (Mindful Money, or Think and Grow Rich)? Is Caitlin Moran’s How to Be a Woman self-help? Or the Essays of Montaigne?

Self-help – although I would prefer the term “self-curiosity” – is almost as broad a genre as fiction. Just as there are a lot of turkeys in literature, there are plenty in the self-help section, some of them remarkably successful despite – or because of – their idiocy. My personal nominations for the closest tosh-to-success correlation would include The Secret, You Can Heal Your Life and The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up – but that is narrowing down a very wide field.

In the minority are the intelligent and worthwhile books – but they can be found. I have enjoyed so-called pop psychology and spirituality books ever since I discovered Families and How to Survive Them by John Cleese and Robin Skynner in the 1980s, and Depression: The Way out of Your Prison by Dorothy Rowe at around the same time.

The Cleese book is a bit dated now, but Rowe’s set me off on a road that I am still following. She is what you might call a non-conforming Buddhist who introduced me to the writing of Alan Watts ( another non-conformer) whose The Meaning of Happiness and The Book have informed my life and worldview ever since.

The irony is that books of this particular stripe point you in a direction almost the opposite of most self-help books. Because, from How to Win Friends and Influence People through to The Power of Positive Thinking and Who Moved My Cheese?, “positive thinking” seems to be the unifying principle (although now partially supplanted by “mindfulness”).

The books I draw sustenance from contain the opposite wisdom. This isn’t negativity. It’s acceptance. Such thinking does not at first glance point you towards the destination of a happier life, which is probably why such tomes are far less popular than their bestselling peers. Yet these counter self-help books have a remarkable amount in common.

Most of them have Buddhism or Stoicism underpinning their thoughts. And they offer a different, and perhaps harder, road to happiness: not through effort, or willpower, or struggle with yourself, but through the forthright facing of facts that most of us prefer not to accept or think about.

Whether Seneca, or Nietzsche, Viktor Frankl or Rowe, Watts or Oliver Burkeman (The Antidote), or most recently Jordan B Peterson (12 Rules for Life), these thinkers all say much the same thing. Stop pretending. Get real.

It is not easy advice. Reality – now as ever – is unpopular, and for good reason. But the great thing about these self-help books is that, while giving sound advice, they are clear-eyed in acknowledging the truth: that happiness is not a given for anyone, there is no magic way of getting “it” – and that, crucially, pursuing it (or even believing in it), is one of the biggest obstacles to actually receiving it.

Such writers suggest the radical path to happiness comes from recognising the inevitability of unhappiness that comes as a result of the human birthright, that is, randomness, mortality, transitoriness, uncertainty and injustice. In other words, all the things we naturally shy away from and spend a huge amount of time and painful mental effort denying or trying not to think about.

Peterson perhaps puts it too strongly to say “life is catastrophe”, and the Buddha is out of date with “life is suffering”. Such strong medicine is understandably hard to take for many people in the comfortable and pleasure-seeking west. And despite what both Peterson and the Buddha say, not everyone suffers all that much.

Some people are just born happy or are lucky, or both, and are either incapable of feeling, or fortunate enough to never to have felt, a great deal in the way of pain or trauma. They are the people who never buy self-help books. But such individuals, I would suggest (although I can’t prove it), are the exception rather than the rule. The rest of us are simply pretending, to ourselves and to others, in order not to feel like failures.

But unhappiness is not failure. It is not pessimistic or morbid to say, for most of us, that life can be hard and that conflict is intrinsic to being and that mortality shadows our waking hours.

In fact it is life-affirming – because once you stop displacing these fears into everyday neuroses, life becomes tranquil, even when it is painful. And during those difficult times of loss and pain, to assert “this is the mixed package called life, and I embrace it in all its positive and negative aspects” shows real courage, rather than hiding in flickering, insubstantial fantasies of control, mysticism, virtue or wishful thinking.

That, as Dorothy Rowe says, is the real secret – that there is no secret.

Booksellers have announced that sales of self-help books are at record levels. The cynics out there will sigh deeply in resignation, even though I suspect they don’t really have a clear idea of what a self-help book is (or could be). Then again, no one has much of an idea what a self-help book is. Is it popular psychology (such as Blink, or Daring Greatly)? Is it spirituality (The Power of Now, or A Course in Miracles)? Or a combination of both (The Road Less Travelled)?

Is it about “success” (The Seven Secrets of Successful People) or accumulating money (Mindful Money, or Think and Grow Rich)? Is Caitlin Moran’s How to Be a Woman self-help? Or the Essays of Montaigne?

Self-help – although I would prefer the term “self-curiosity” – is almost as broad a genre as fiction. Just as there are a lot of turkeys in literature, there are plenty in the self-help section, some of them remarkably successful despite – or because of – their idiocy. My personal nominations for the closest tosh-to-success correlation would include The Secret, You Can Heal Your Life and The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up – but that is narrowing down a very wide field.

In the minority are the intelligent and worthwhile books – but they can be found. I have enjoyed so-called pop psychology and spirituality books ever since I discovered Families and How to Survive Them by John Cleese and Robin Skynner in the 1980s, and Depression: The Way out of Your Prison by Dorothy Rowe at around the same time.

The Cleese book is a bit dated now, but Rowe’s set me off on a road that I am still following. She is what you might call a non-conforming Buddhist who introduced me to the writing of Alan Watts ( another non-conformer) whose The Meaning of Happiness and The Book have informed my life and worldview ever since.

The irony is that books of this particular stripe point you in a direction almost the opposite of most self-help books. Because, from How to Win Friends and Influence People through to The Power of Positive Thinking and Who Moved My Cheese?, “positive thinking” seems to be the unifying principle (although now partially supplanted by “mindfulness”).

The books I draw sustenance from contain the opposite wisdom. This isn’t negativity. It’s acceptance. Such thinking does not at first glance point you towards the destination of a happier life, which is probably why such tomes are far less popular than their bestselling peers. Yet these counter self-help books have a remarkable amount in common.

Most of them have Buddhism or Stoicism underpinning their thoughts. And they offer a different, and perhaps harder, road to happiness: not through effort, or willpower, or struggle with yourself, but through the forthright facing of facts that most of us prefer not to accept or think about.

Whether Seneca, or Nietzsche, Viktor Frankl or Rowe, Watts or Oliver Burkeman (The Antidote), or most recently Jordan B Peterson (12 Rules for Life), these thinkers all say much the same thing. Stop pretending. Get real.

It is not easy advice. Reality – now as ever – is unpopular, and for good reason. But the great thing about these self-help books is that, while giving sound advice, they are clear-eyed in acknowledging the truth: that happiness is not a given for anyone, there is no magic way of getting “it” – and that, crucially, pursuing it (or even believing in it), is one of the biggest obstacles to actually receiving it.

Such writers suggest the radical path to happiness comes from recognising the inevitability of unhappiness that comes as a result of the human birthright, that is, randomness, mortality, transitoriness, uncertainty and injustice. In other words, all the things we naturally shy away from and spend a huge amount of time and painful mental effort denying or trying not to think about.

Peterson perhaps puts it too strongly to say “life is catastrophe”, and the Buddha is out of date with “life is suffering”. Such strong medicine is understandably hard to take for many people in the comfortable and pleasure-seeking west. And despite what both Peterson and the Buddha say, not everyone suffers all that much.

Some people are just born happy or are lucky, or both, and are either incapable of feeling, or fortunate enough to never to have felt, a great deal in the way of pain or trauma. They are the people who never buy self-help books. But such individuals, I would suggest (although I can’t prove it), are the exception rather than the rule. The rest of us are simply pretending, to ourselves and to others, in order not to feel like failures.

But unhappiness is not failure. It is not pessimistic or morbid to say, for most of us, that life can be hard and that conflict is intrinsic to being and that mortality shadows our waking hours.

In fact it is life-affirming – because once you stop displacing these fears into everyday neuroses, life becomes tranquil, even when it is painful. And during those difficult times of loss and pain, to assert “this is the mixed package called life, and I embrace it in all its positive and negative aspects” shows real courage, rather than hiding in flickering, insubstantial fantasies of control, mysticism, virtue or wishful thinking.

That, as Dorothy Rowe says, is the real secret – that there is no secret.

Tuesday, 10 May 2016

Dealing with parents' mortality

Rohit Brijnath in The Straits Times

My father, 81, and I talk occasionally about his death. At breakfast he, not an ailing man, can turn into a prophet of doom amidst spoonfuls of cereal. "I have two years left," he will pronounce, to which I reply that his predictions are unreliable since he has been saying this for the past six years. My mother, 83, laughs and he smiles. We are all, impossibly, trying to meet death with some humour and grace.

I am sounding braver than I actually feel for the inevitability of a parent's death is like a shadow that walks quietly with most of us. A 40-year-old woman I met recently revealed that when her parents are asleep, she stands over their beds in the dark, waiting for a tiny movement, a proof of life. Mortality is life's most towering lesson, not to be feared but gradually understood.

My parents' eventual death is hardly a preoccupation for me but for those of us who live on foreign shores, it's always there, lingering on the outskirts of our daily lives. It is hard to explain the two-second terror of the surprise phone call from our homes far away. I answer with a question that is always tense and terse: "Everything OK?" My father replies: "Of course, beta (son)."

Death will come, and somehow, it will always be imperfect. In old Bollywood films, parents made long, weepy speeches about family and love and then their heads fell dramatically to the side. Reality is never so scripted. The devilry of distance - I live two flights from my parents - means that it is unlikely we will be home in time. We do not want our parents to linger and yet the heart attack's unpredictable finality leaves no time for farewell. We are presuming, of course, that there is such a thing as a graceful goodbye. Perhaps it is in how we live with them that is more vital.

I talk occasionally to my parents about death, not because I am morbid but because I am inquisitive about mortality and because I do not want them to be scared or alone. Yet I find it is they who reassure me.

They return from frequent funerals, friends gone and family lost, and speak with voice softer but spirit intact. My father retreats deeper into his sofa and philosophy and tells me: "The whole, wonderful, joyful, exhilarating business of evolution would not exist if we were immortal." There can rarely be an equanimity about death - we all fear pain and indignity on the way there and we all feel loss - but sometimes we might strive for an acceptance that all things must finish.

Few other struggles are as impartial as ageing and illness, and the mortality of a parent. Every friend I spoke to carried a separate apprehension. A banker told me she is unafraid and yet had already asked close friends to attend her parents' funerals. Emotionally and practically, she knows she will need support. An executive, her parents still together after 61 years, sinks as she considers one parent left behind, like an old, steadied ship whose moorings have been cruelly cut. A flinty investigative journalist, bound to her mother who is her only parent alive, wonders about her sanity once left alone.

We feel hesitant often to raise some subjects with our parents as if they are too impertinent or inconvenient and yet practicality has a place. Was a will written, a DNR (Do Not Resuscitate) ordered, all these seemingly minor matters which leave shaken families divided in emergency rooms. Do we know what our parents wish and how they want to go?

Clarity is the great courtesy that my friend Sharda's mother offered her: no life support, no unnecessary surgery. Another pal, Samar, has a paper packet at home given to him a while ago by his parents and only recently did he find the nerve to peek in. No religious rituals, his parents wrote; our bodies to be donated for medical purposes, they noted.

I found nothing grim in this but saw it instead as a gentle gift to their son by giving him answers to questions he cannot bear to ask. There was also in the giving of their bodies to science a beautiful, moral clarity. In their 80s, they had understood that in death, they might be able to do what so few of us can do while living: save a life.

Samar sees his parents every day and I call India every second day. In my wrestle with the eventual truth of a parent-less planet, I have learnt five things. The first is contact. To hear, see, touch. To talk and to learn. My father recently mentioned in conversation about the composers Johann Strauss Senior and Junior. I didn't tell him I thought there was only one. So thanks, dad.

Second, to speak your mind, to leave nothing unsaid, for in the sharing of love a relationship comes alive. Not everyone can find the words but regret is an incurable ache.

Third, mine them for stories, of where they came from, hardship they hurdled, love they found, museums they visited, people they became, dreams they left behind, times they lived in, fears they wore. If I don't write them down, then stories dim and histories die and there is nothing to carry forward.

Fourth, and this my mother is teaching me, is to respect choice. "Fight, fight" against age, against illness, we tell our parents, often selfishly, but not everything must be raged against. Dylan Thomas was wrong, sometimes you have to go gentle into that good night. Sometimes, life has been enough, a weariness comes to rest, all accounts are settled and people want to turn to the wall, away from life and slip away. As my closest friend, Namita, still grieving over a mother she recently lost, told me: "There is a great love in letting people go."

Fifth, and I am lousy at this, don't steal their autonomy and instead respect their choices, hear their opinions, let them be free to arrange the rhythms of their life. My brothers and I are always trying to buy our parents a TV, a fridge, as if we cannot fathom that their life does not need a new shine. Yet it is fine as it is. So what if the letters on my mother's keyboard wore away, she has not forgotten the unique order of this alphabet.

Still I search for clarity amidst the clutter of life's incessant questions. I wade, like us all, through the truths of ageing and loss. I think of a relative who cannot find a way to open cupboards and wander through the accumulated life of her parents she has recently lost. I am moved by a friend, a civil servant whose father passed away a while ago and who tells me: "I don't fear death. I feel I have had a fulfilling stint with my mum." We are, all of us, a forest of crooked trees, leaning on each other.

I find reassurance in the reality that my parents, hardly wealthy, not poor, have lived rich lives. My mother now sits with the stillness of a painting and reads. My father writes to me: "I am not frightened by death. I will be sad that I can no longer look at Michelangelo's David, Picasso's Guernica, listen to the cool jazz of Bill Evans' piano or smell the aroma of a beautiful woman!" Today he has gone, as he does many Sundays, to listen and learn from a younger man about his beloved Strauss and Bach and Mozart. To this music, always he comes alive.

My father, 81, and I talk occasionally about his death. At breakfast he, not an ailing man, can turn into a prophet of doom amidst spoonfuls of cereal. "I have two years left," he will pronounce, to which I reply that his predictions are unreliable since he has been saying this for the past six years. My mother, 83, laughs and he smiles. We are all, impossibly, trying to meet death with some humour and grace.

I am sounding braver than I actually feel for the inevitability of a parent's death is like a shadow that walks quietly with most of us. A 40-year-old woman I met recently revealed that when her parents are asleep, she stands over their beds in the dark, waiting for a tiny movement, a proof of life. Mortality is life's most towering lesson, not to be feared but gradually understood.

My parents' eventual death is hardly a preoccupation for me but for those of us who live on foreign shores, it's always there, lingering on the outskirts of our daily lives. It is hard to explain the two-second terror of the surprise phone call from our homes far away. I answer with a question that is always tense and terse: "Everything OK?" My father replies: "Of course, beta (son)."

Death will come, and somehow, it will always be imperfect. In old Bollywood films, parents made long, weepy speeches about family and love and then their heads fell dramatically to the side. Reality is never so scripted. The devilry of distance - I live two flights from my parents - means that it is unlikely we will be home in time. We do not want our parents to linger and yet the heart attack's unpredictable finality leaves no time for farewell. We are presuming, of course, that there is such a thing as a graceful goodbye. Perhaps it is in how we live with them that is more vital.

I talk occasionally to my parents about death, not because I am morbid but because I am inquisitive about mortality and because I do not want them to be scared or alone. Yet I find it is they who reassure me.

They return from frequent funerals, friends gone and family lost, and speak with voice softer but spirit intact. My father retreats deeper into his sofa and philosophy and tells me: "The whole, wonderful, joyful, exhilarating business of evolution would not exist if we were immortal." There can rarely be an equanimity about death - we all fear pain and indignity on the way there and we all feel loss - but sometimes we might strive for an acceptance that all things must finish.

Few other struggles are as impartial as ageing and illness, and the mortality of a parent. Every friend I spoke to carried a separate apprehension. A banker told me she is unafraid and yet had already asked close friends to attend her parents' funerals. Emotionally and practically, she knows she will need support. An executive, her parents still together after 61 years, sinks as she considers one parent left behind, like an old, steadied ship whose moorings have been cruelly cut. A flinty investigative journalist, bound to her mother who is her only parent alive, wonders about her sanity once left alone.

We feel hesitant often to raise some subjects with our parents as if they are too impertinent or inconvenient and yet practicality has a place. Was a will written, a DNR (Do Not Resuscitate) ordered, all these seemingly minor matters which leave shaken families divided in emergency rooms. Do we know what our parents wish and how they want to go?

Clarity is the great courtesy that my friend Sharda's mother offered her: no life support, no unnecessary surgery. Another pal, Samar, has a paper packet at home given to him a while ago by his parents and only recently did he find the nerve to peek in. No religious rituals, his parents wrote; our bodies to be donated for medical purposes, they noted.

I found nothing grim in this but saw it instead as a gentle gift to their son by giving him answers to questions he cannot bear to ask. There was also in the giving of their bodies to science a beautiful, moral clarity. In their 80s, they had understood that in death, they might be able to do what so few of us can do while living: save a life.

Samar sees his parents every day and I call India every second day. In my wrestle with the eventual truth of a parent-less planet, I have learnt five things. The first is contact. To hear, see, touch. To talk and to learn. My father recently mentioned in conversation about the composers Johann Strauss Senior and Junior. I didn't tell him I thought there was only one. So thanks, dad.

Second, to speak your mind, to leave nothing unsaid, for in the sharing of love a relationship comes alive. Not everyone can find the words but regret is an incurable ache.

Third, mine them for stories, of where they came from, hardship they hurdled, love they found, museums they visited, people they became, dreams they left behind, times they lived in, fears they wore. If I don't write them down, then stories dim and histories die and there is nothing to carry forward.

Fourth, and this my mother is teaching me, is to respect choice. "Fight, fight" against age, against illness, we tell our parents, often selfishly, but not everything must be raged against. Dylan Thomas was wrong, sometimes you have to go gentle into that good night. Sometimes, life has been enough, a weariness comes to rest, all accounts are settled and people want to turn to the wall, away from life and slip away. As my closest friend, Namita, still grieving over a mother she recently lost, told me: "There is a great love in letting people go."

Fifth, and I am lousy at this, don't steal their autonomy and instead respect their choices, hear their opinions, let them be free to arrange the rhythms of their life. My brothers and I are always trying to buy our parents a TV, a fridge, as if we cannot fathom that their life does not need a new shine. Yet it is fine as it is. So what if the letters on my mother's keyboard wore away, she has not forgotten the unique order of this alphabet.

Still I search for clarity amidst the clutter of life's incessant questions. I wade, like us all, through the truths of ageing and loss. I think of a relative who cannot find a way to open cupboards and wander through the accumulated life of her parents she has recently lost. I am moved by a friend, a civil servant whose father passed away a while ago and who tells me: "I don't fear death. I feel I have had a fulfilling stint with my mum." We are, all of us, a forest of crooked trees, leaning on each other.

I find reassurance in the reality that my parents, hardly wealthy, not poor, have lived rich lives. My mother now sits with the stillness of a painting and reads. My father writes to me: "I am not frightened by death. I will be sad that I can no longer look at Michelangelo's David, Picasso's Guernica, listen to the cool jazz of Bill Evans' piano or smell the aroma of a beautiful woman!" Today he has gone, as he does many Sundays, to listen and learn from a younger man about his beloved Strauss and Bach and Mozart. To this music, always he comes alive.

Wednesday, 16 November 2011

Criticism of Schumacher - if you curtail growth, living standards drop

Schumacher was no radical – if you curtail growth, living standards drop

By suggesting it's

better to be economically poorer and spiritually richer, Schumacher

ignores links between growth and wellbeing

Consumer revolution … a customer inspects washing machines at a supermarket in Wuhan, China. Photograph: Darley Shen/Reuters

EF Schumacher's Small is Beautiful is widely viewed as a humanistic and radical tract. Nothing could be further from the truth. Viewed in its proper context it is both profoundly anti-human and deeply conservative.

The central idea in Schumacher's text is that there is a natural limit to economic growth. As he put it: "Economic growth, which viewed from the point of view of economics, physics, chemistry and technology, has no discernible limit, must necessarily run into decisive bottlenecks when viewed from the point of view of the environmental sciences."

Schumacher objected to organising the economy on a large scale precisely because he believed that more prosperity would damage the environment. He correctly understood that small-scale communities cannot produce nearly as much as those operating on a regional or global scale. A modern car, for example, typically relies on components, raw materials and know-how from around the globe. From the perspective of Schumacher's "Buddhist economics", it is better for people to be poorer in economic terms if they can be spiritually richer.

This argument flies against a huge weight of evidence showing that material advance is closely bound up with progress more generally. The past two centuries of modern economic growth have seen huge advances in human welfare along with technological innovation and social advance. Perhaps the most striking single indicator of this improvement is the increase in human life expectancy from about 30 in 1800 to nearly 70 today. Note that this is a global average, so it includes the billions of people who live in poor countries as well as the minority who live in rich ones.

Almost every other measure of wellbeing has increased hugely over the long term, including infant mortality, food consumption and level of education. Most of humanity, even in the developing world, has access to services our ancestors could only have dreamt of, including electricity, clean water, sanitation and mobile phones.

None of the arguments used by Schumacher's followers to counter this narrative of progress are convincing. Greens often side-step the broader case for growth by deriding the accumulation of consumer goods and services. Environmentalist arguments have more than a tinge of elitism, with comfortably middle-class greens scoffing at the masses for wanting flat-screen televisions and foreign holidays. It should also be remembered that some consumer goods, such as washing machines, have directly led to huge improvements in human welfare.

Anti-consumerism reveals more about the narrowness of the green vision than it does about economic growth. Viewing rising prosperity simply in terms of consumer goods is incredibly blinkered. Growth provides the resources for much else including airports, art galleries, hospitals, museums, power stations, railways, roads, schools and universities. Popular prosperity provides the bedrock for much that we value in contemporary society.

Another common green rebuttal to the benefits of growth is to point to the existence of inequality. Of course it is true that there are huge disparities both within countries as well as between the developed and developing world. The key question, however, is how best to tackle the problem. From Schumacher's perspective it is desirable to reduce the living standards of everyone except the poorest of the poor. His is a narrative of shared sacrifice and lower living standards for almost all. The alternative vision, the traditional position of the left, was to argue for plenty for everyone.

Finally, there is the argument about the environment itself. The most popular variant of the idea of a natural limit nowadays is that growth inevitably means runaway climate change. However, there is plenty of evidence to the contrary. There are many forms of energy, including nuclear, that do not emit greenhouse gases. There are also ways to adapt to global warming such as building higher sea walls. Since such measures are expensive it will take more resources to pay for them; which means more economic growth rather than less. If anything the green drive to curb prosperity is likely to undermine our capacity to tackle climate change.

Schumacher's fundamentally conservative argument chimes well with those who want to reconcile us to austerity. It suits those in power for the mass of the population to accept the need to make do with less. Under such circumstances it is no surprise that David Cameron, like his international peers, is keen for us to focus on individual contentment rather than material prosperity.

It is hard to imagine a more anti-human outlook than one advocating a sharp fall in living standards for the bulk of the world's population.

Tuesday, 30 August 2011

Why you won't find the meaning of life

By Spengler

Much as I admire the late Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist Viktor Frankl, who turned his horrific experience at Auschwitz into clinical insights, the notion of "man's search for meaning" seems inadequate. Just what about man qualifies him to search for meaning, whatever that might be?

The German playwright Bertolt Brecht warned us against the practice in The Threepenny Opera:

Ja, renne nach dem Gluck

Doch renne nicht zu sehr

Denn alle rennen nach dem Gluck

Das Gluck lauft hinterher.

(Sure, run after happiness, but don't run too hard, because while everybody's running after happiness, it moseys along somewhere behind them).

Brecht (1898-1956) was the kind of character who gave Nihilism a bad name, to be sure, but he had a point. There is something perverse in searching for the meaning of life. It implies that we don't like our lives and want to discover something different. If we don't like living to begin with, we are in deep trouble.

Danish philosopher, theologian and religious author Soren Kierkegaard portrayed his Knight of Faith as the sort of fellow who enjoyed a pot roast on Sunday afternoon. If that sort of thing doesn't satisfy us (feel free to substitute something else than eating), just what is it that we had in mind?

People have a good reason to look at life cross-eyed, because it contains a glaring flaw - that we are going to die, and we probably will become old and sick and frail before we do so. All the bric-a-brac we accumulate during our lifetimes will accrue to other people, if it doesn't go right into the trash, and all the little touches of self-improvement we added to our personality will disappear - the golf stance, the macrame skills, the ability to play the ukulele and the familiarity with the filmography of Sam Pekinpah.

These examples trivialize the problem, of course. If we search in earnest for the meaning of life, then we might make heroic efforts to invent our own identity. That is the great pastime of the past century's intellectuals. Jean-Paul Sartre, the sage and eventual self-caricature of Existentialism, instructed us that man's existence precedes his essence, and therefore can invent his own essence more or less as he pleases. That was a silly argument, but enormously influential.

Sartre reacted to the advice of Martin Heidegger (the German existentialist from whom Jean-Paul Sartre cribbed most of his metaphysics). Heidegger told us that our "being" really was being-unto-death, for our life would end, and therefore is shaped by how we deal with the certainty of death. (Franz Kafka put the same thing better: "The meaning of life is that it ends.") Heidegger (1889-1976) thought that to be "authentic" mean to submerge ourselves into the specific conditions of our time, which for him meant joining the Nazi party. That didn't work out too well, and after the war it became every existentialist for himself. Everyone had the chance to invent his own identity according to taste.

Few of us actually read Sartre (and most of us who do regret it), and even fewer read the impenetrable Heidegger, whom I have tried to make more accessible by glossing his thought in Ebonics (The secret that Leo Strauss never revealed, Asia Times Online, May 13, 2003.) But most of us remain the intellectual slaves of 20th century existentialism notwithstanding. We want to invent our own identities, which implies doing something unique.

This has had cataclysmic consequences in the arts. To be special, an artist must create a unique style, which means that there will be as many styles as artists. It used to be that artists were trained within a culture, so that thousands of artists and musicians painted church altar pieces and composed music for Sunday services for the edification of ordinary church-goers.

Out of such cultures came one or two artists like Raphael or Bach. Today's serious artists write for a miniscule coterie of aficionados in order to validate their own self-invention, and get university jobs if they are lucky, inflicting the same sort of misery on their students. By the time they reach middle age, most artists of this ilk come to understand that they have not found the meaning of life. In fact, they don't even like what they are doing, but as they lack professional credentials to do anything else, they keep doing it.

The high art of the Renaissance or Baroque, centered in the churches or the serious theater, has disappeared. Ordinary people can't be expected to learn a new style every time they encounter the work of a new artist (neither can critics, but they pretend to). The sort of art that appeals to a general audience has retreated into popular culture. That is not the worst sort of outcome. One of my teachers observes that the classical style of composition never will disappear, because the movies need it; it is the only sort of music that can tell a story.

Most people who make heroic efforts at originality learn eventually that they are destined for no such thing. If they are lucky, they content themselves with Kierkegaard's pot roast on Sunday afternoon and other small joys, for example tenure at a university. But no destiny is more depressing than that of the artist who truly manages to invent a new style and achieve recognition for it.

He recalls the rex Nemorensis, the priest of Diana at Nemi who according to Ovid won his office by murdering his predecessor, and will in turn be murdered by his eventual successor. The inventor of a truly new style has cut himself off from the past, and will in turn be cut off from the future by the next entrant who invents a unique and individual style.

The only thing worse than searching in vain for the meaning of life within the terms of the 20th century is to find it, for it can only be a meaning understood by the searcher alone, who by virtue of the discovery is cut off from future as well as past. That is why our image of the artist is a young rebel rather than an elderly sage. If our rebel artists cannot manage to die young, they do the next best thing, namely disappear from public view, like J D Salinger or Thomas Pynchon. The aging rebel is in the position of Diana's priest who sleeps with sword in hand and one eye open, awaiting the challenger who will do to him what he did to the last fellow to hold the job.

Most of us have no ambitions to become the next Jackson Pollack or Damien Hirst. Instead of Heidegger's being-unto-death, we acknowledge being-unto-cosmetic surgery, along with exercise, Botox and anti-oxidants. We attempt to stay young indefinitely. Michael Jackson, I argued in a July 2009 obituary, became a national hero because more than any other American he devoted his life to the goal of remaining an adolescent. His body lies moldering in the grave (in fact, it was moldering long before it reached the grave) but his spirit soars above an America that proposes to deal with the problem of mortality by fleeing from it. (See Blame Michael Jackson Asia Times Online, July 14, 2009.)

A recent book by the sociologist Eric Kaufmann (Will the Religious Inherit the Earth?) makes the now-common observation that secular people have stopped having children. As a secular writer, he bewails this turn of events, but concedes that it has occurred for a reason: "The weakest link in the secular account of human nature is that it fails to account for people's powerful desire to seek immortality for themselves and their loved ones."

Traditional society had to confront infant mortality as well as death by hunger, disease and war. That shouldn't be too troubling, however: "We may not be able to duck death completely, but it becomes so infrequent that we can easily forget about it."

That is a Freudian slip for the record books. Contrary to what Professor Kaufmann seems to be saying, the mortality rate for human beings remains at 100%, where it always was. But that is not how we think about it. We understand the concept of death, just not as it might apply to us.

If we set out to invent our own identities, then by definition we must abominate the identities of our parents and our teachers. Our children, should we trouble to bring any into the world, also will abominate ours. If self-invention is the path to the meaning of life, it makes the messy job of bearing and raising children a superfluous burden, for we can raise our children by no other means than to teach them contempt for us, both by instruction, and by the example of set in showing contempt to our own parents.

That is why humanity has found no other way to perpetuate itself than by the continuity of tradition. A life that is worthwhile is one that is worthwhile in all its phases, from youth to old age. Of what use are the elderly? In a viable culture they are the transmitters of the accumulated wisdom of the generations. We will take the trouble to have children of our own only when we anticipate that they will respect us in our declining years, not merely because they tolerate us, but because we will have something yet to offer to the young.

In that case, we do not discover the meaning of life. We accept it, rather, as it is handed down to us. Tradition by itself is no guarantee of cultural viability. Half of the world's 6,700 languages today are spoken by small tribes in New Guinea, whose rate of extinction is frightful. Traditions perfected over centuries of isolated existence in Neolithic society can disappear in a few years in the clash with modernity. But there are some traditions in the West that have survived for millennia and have every hope of enduring for millennia still.

For those of you who still are searching for the meaning of life, the sooner you figure out that the search itself is the problem, the better off you will be. Since the Epic of Gilgamesh in the third millennium BC, our search has not been for meaning, but for immortality. And as the gods told Gilgamesh, you can't find immortality by looking for it. Better to find a recipe for pot roast.

Spengler is channeled by David P Goldman. View comments on this article in Spengler's Expat Bar forum.

(Copyright 2011 Asia Times Online (Holdings) Ltd. All rights reserved. Please contact us about sales, syndication and republishing.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)