'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label stoicism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label stoicism. Show all posts

Thursday, 12 January 2023

Saturday, 1 June 2019

The winner’s wisdom of Silicon Valley Stoics

Letting go of comfort and control makes sense — if you already have those things writes Janan Ganesh in The FT.

The late George Michael used to hail marijuana as the optimal drug — for those who have already achieved their ambitions. For the rest of us, he warned, its mellowing properties would sap our drive. “You’ve got to be in the right position in life,” said a man who kept houses in both Hampstead and Highgate, which, if you know Manhattan better, is like keeping homes on East 75th Street and West 75th Street.

An idea that works for an established winner can be utterly ruinous for a mere aspirant.

For some reason, this insight comes to mind whenever I encounter the modern fad for Stoicism. Which, given that I have access to the internet, and to the state of California, is rather a lot.

In common parlance, Stoicism used to mean nothing more specific than a kind of grin-and-bear-it fortitude. But in recent years, the actual philosophy of Seneca and Marcus Aurelius has rallied too, if in glib and half-understood form.

The new Stoicism calls for — and here I paraphrase — a virtuous rather than joy-centred life. It often takes the guise of self-denial: the modern Stoic volunteers for ice baths and sparse diets. It also manifests as a certain detachment from the vicissitudes of life. The modern Stoic does not rail against external variables. Enemies, disasters and random surprises are all part of the natural order.

You can recognise the parallels with the Zen vogue of yesteryear. And you can guess who has fallen hardest for this creed. It has made deep inroads into the educated rich, and into the tech cognoscenti in particular. Through their cultural reach — the podcasts, the Ted talks — it is fanning out from Silicon Valley to other pockets of well-fed ennui.

There is a something to be said for this elevated version of self-help. Certain habits I keep, such as a minimal intake of media, are unconsciously neo-Stoic. And while some of its followers would fall for any passing -ism or -ology (Tim Ferriss, Arianna Huffington), others have brains like industrial lasers.

All the more reason, then, for the smarter among them to insert a qualifier: letting go of comfort and control makes perfect sense (and I really must resort to italics here) once you already have these things. The new Stoicism is a kind of victor’s wisdom. It simplifies the lives of people who are beset with extreme surplus. This is not a universal problem. Modern Stoics should not pretend to universal (or even broad) relevance. “Very little is needed to make a happy life”, wrote Marcus Aurelius, the ultimate owner of everything in the known world at the time. At least he did not try this line on the masses. His Meditations were never meant for publication. Would that his 21st-century heirs were so coy.

As a way of de-stressing powerful millionaires, neo-Stoic thought is hard to fault. For those striving for some power and millions to be stressed about, it rather speaks over their heads. Most of us aspire to material comforts or (another Stoic no-no) popularity. It is fine to achieve these things and then decide to keep them in check, lest they drive one mad. But to warn others off them, or pretend they can get them by not craving them, is life advice at its most de haut en bas.

You will notice that the smarmy de-emphasis on earthly pleasures stops well short of total renunciation. Like some credulous Sloane on an equatorial gap year, the modern Stoic idealises hardship precisely because they can pick and choose their exposure to it. “Practising poverty,” they call it, with Marie Antoinette’s self-awareness.

Perhaps the worst of it is the deception of those who are just starting out in life. Unless “22 Stoic Truth-Bombs From Marcus Aurelius That Will Make You Unf***withable” is pitched at retirees, the internet crawls with bad Stoic advice for the young. The premise is that what answers to the needs of those in the 99th percentile of wealth and power is at all relevant to those trying to break out of, say, the 50th. The new Stoicism is not useless. It promises a measure of serenity in a world that militates against it. You’ve just got to be in the right position in life.

The late George Michael used to hail marijuana as the optimal drug — for those who have already achieved their ambitions. For the rest of us, he warned, its mellowing properties would sap our drive. “You’ve got to be in the right position in life,” said a man who kept houses in both Hampstead and Highgate, which, if you know Manhattan better, is like keeping homes on East 75th Street and West 75th Street.

An idea that works for an established winner can be utterly ruinous for a mere aspirant.

For some reason, this insight comes to mind whenever I encounter the modern fad for Stoicism. Which, given that I have access to the internet, and to the state of California, is rather a lot.

In common parlance, Stoicism used to mean nothing more specific than a kind of grin-and-bear-it fortitude. But in recent years, the actual philosophy of Seneca and Marcus Aurelius has rallied too, if in glib and half-understood form.

The new Stoicism calls for — and here I paraphrase — a virtuous rather than joy-centred life. It often takes the guise of self-denial: the modern Stoic volunteers for ice baths and sparse diets. It also manifests as a certain detachment from the vicissitudes of life. The modern Stoic does not rail against external variables. Enemies, disasters and random surprises are all part of the natural order.

You can recognise the parallels with the Zen vogue of yesteryear. And you can guess who has fallen hardest for this creed. It has made deep inroads into the educated rich, and into the tech cognoscenti in particular. Through their cultural reach — the podcasts, the Ted talks — it is fanning out from Silicon Valley to other pockets of well-fed ennui.

There is a something to be said for this elevated version of self-help. Certain habits I keep, such as a minimal intake of media, are unconsciously neo-Stoic. And while some of its followers would fall for any passing -ism or -ology (Tim Ferriss, Arianna Huffington), others have brains like industrial lasers.

All the more reason, then, for the smarter among them to insert a qualifier: letting go of comfort and control makes perfect sense (and I really must resort to italics here) once you already have these things. The new Stoicism is a kind of victor’s wisdom. It simplifies the lives of people who are beset with extreme surplus. This is not a universal problem. Modern Stoics should not pretend to universal (or even broad) relevance. “Very little is needed to make a happy life”, wrote Marcus Aurelius, the ultimate owner of everything in the known world at the time. At least he did not try this line on the masses. His Meditations were never meant for publication. Would that his 21st-century heirs were so coy.

As a way of de-stressing powerful millionaires, neo-Stoic thought is hard to fault. For those striving for some power and millions to be stressed about, it rather speaks over their heads. Most of us aspire to material comforts or (another Stoic no-no) popularity. It is fine to achieve these things and then decide to keep them in check, lest they drive one mad. But to warn others off them, or pretend they can get them by not craving them, is life advice at its most de haut en bas.

You will notice that the smarmy de-emphasis on earthly pleasures stops well short of total renunciation. Like some credulous Sloane on an equatorial gap year, the modern Stoic idealises hardship precisely because they can pick and choose their exposure to it. “Practising poverty,” they call it, with Marie Antoinette’s self-awareness.

Perhaps the worst of it is the deception of those who are just starting out in life. Unless “22 Stoic Truth-Bombs From Marcus Aurelius That Will Make You Unf***withable” is pitched at retirees, the internet crawls with bad Stoic advice for the young. The premise is that what answers to the needs of those in the 99th percentile of wealth and power is at all relevant to those trying to break out of, say, the 50th. The new Stoicism is not useless. It promises a measure of serenity in a world that militates against it. You’ve just got to be in the right position in life.

Tuesday, 19 March 2019

The best form of self-help is … a healthy dose of unhappiness

We’re seeking solace in greater numbers than ever. But we’re more likely to find it in reality than in positive thinking writes Tim Lott in The Guardian

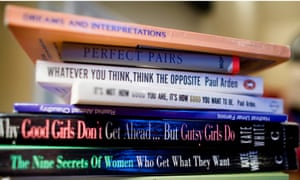

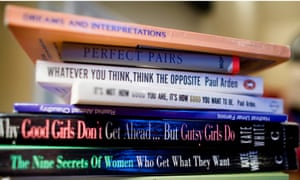

‘Self-help is almost as broad a genre as fiction.’ Photograph: Christopher Thomond/The Guardian

Booksellers have announced that sales of self-help books are at record levels. The cynics out there will sigh deeply in resignation, even though I suspect they don’t really have a clear idea of what a self-help book is (or could be). Then again, no one has much of an idea what a self-help book is. Is it popular psychology (such as Blink, or Daring Greatly)? Is it spirituality (The Power of Now, or A Course in Miracles)? Or a combination of both (The Road Less Travelled)?

Is it about “success” (The Seven Secrets of Successful People) or accumulating money (Mindful Money, or Think and Grow Rich)? Is Caitlin Moran’s How to Be a Woman self-help? Or the Essays of Montaigne?

Self-help – although I would prefer the term “self-curiosity” – is almost as broad a genre as fiction. Just as there are a lot of turkeys in literature, there are plenty in the self-help section, some of them remarkably successful despite – or because of – their idiocy. My personal nominations for the closest tosh-to-success correlation would include The Secret, You Can Heal Your Life and The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up – but that is narrowing down a very wide field.

In the minority are the intelligent and worthwhile books – but they can be found. I have enjoyed so-called pop psychology and spirituality books ever since I discovered Families and How to Survive Them by John Cleese and Robin Skynner in the 1980s, and Depression: The Way out of Your Prison by Dorothy Rowe at around the same time.

The Cleese book is a bit dated now, but Rowe’s set me off on a road that I am still following. She is what you might call a non-conforming Buddhist who introduced me to the writing of Alan Watts ( another non-conformer) whose The Meaning of Happiness and The Book have informed my life and worldview ever since.

The irony is that books of this particular stripe point you in a direction almost the opposite of most self-help books. Because, from How to Win Friends and Influence People through to The Power of Positive Thinking and Who Moved My Cheese?, “positive thinking” seems to be the unifying principle (although now partially supplanted by “mindfulness”).

The books I draw sustenance from contain the opposite wisdom. This isn’t negativity. It’s acceptance. Such thinking does not at first glance point you towards the destination of a happier life, which is probably why such tomes are far less popular than their bestselling peers. Yet these counter self-help books have a remarkable amount in common.

Most of them have Buddhism or Stoicism underpinning their thoughts. And they offer a different, and perhaps harder, road to happiness: not through effort, or willpower, or struggle with yourself, but through the forthright facing of facts that most of us prefer not to accept or think about.

Whether Seneca, or Nietzsche, Viktor Frankl or Rowe, Watts or Oliver Burkeman (The Antidote), or most recently Jordan B Peterson (12 Rules for Life), these thinkers all say much the same thing. Stop pretending. Get real.

It is not easy advice. Reality – now as ever – is unpopular, and for good reason. But the great thing about these self-help books is that, while giving sound advice, they are clear-eyed in acknowledging the truth: that happiness is not a given for anyone, there is no magic way of getting “it” – and that, crucially, pursuing it (or even believing in it), is one of the biggest obstacles to actually receiving it.

Such writers suggest the radical path to happiness comes from recognising the inevitability of unhappiness that comes as a result of the human birthright, that is, randomness, mortality, transitoriness, uncertainty and injustice. In other words, all the things we naturally shy away from and spend a huge amount of time and painful mental effort denying or trying not to think about.

Peterson perhaps puts it too strongly to say “life is catastrophe”, and the Buddha is out of date with “life is suffering”. Such strong medicine is understandably hard to take for many people in the comfortable and pleasure-seeking west. And despite what both Peterson and the Buddha say, not everyone suffers all that much.

Some people are just born happy or are lucky, or both, and are either incapable of feeling, or fortunate enough to never to have felt, a great deal in the way of pain or trauma. They are the people who never buy self-help books. But such individuals, I would suggest (although I can’t prove it), are the exception rather than the rule. The rest of us are simply pretending, to ourselves and to others, in order not to feel like failures.

But unhappiness is not failure. It is not pessimistic or morbid to say, for most of us, that life can be hard and that conflict is intrinsic to being and that mortality shadows our waking hours.

In fact it is life-affirming – because once you stop displacing these fears into everyday neuroses, life becomes tranquil, even when it is painful. And during those difficult times of loss and pain, to assert “this is the mixed package called life, and I embrace it in all its positive and negative aspects” shows real courage, rather than hiding in flickering, insubstantial fantasies of control, mysticism, virtue or wishful thinking.

That, as Dorothy Rowe says, is the real secret – that there is no secret.

Booksellers have announced that sales of self-help books are at record levels. The cynics out there will sigh deeply in resignation, even though I suspect they don’t really have a clear idea of what a self-help book is (or could be). Then again, no one has much of an idea what a self-help book is. Is it popular psychology (such as Blink, or Daring Greatly)? Is it spirituality (The Power of Now, or A Course in Miracles)? Or a combination of both (The Road Less Travelled)?

Is it about “success” (The Seven Secrets of Successful People) or accumulating money (Mindful Money, or Think and Grow Rich)? Is Caitlin Moran’s How to Be a Woman self-help? Or the Essays of Montaigne?

Self-help – although I would prefer the term “self-curiosity” – is almost as broad a genre as fiction. Just as there are a lot of turkeys in literature, there are plenty in the self-help section, some of them remarkably successful despite – or because of – their idiocy. My personal nominations for the closest tosh-to-success correlation would include The Secret, You Can Heal Your Life and The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up – but that is narrowing down a very wide field.

In the minority are the intelligent and worthwhile books – but they can be found. I have enjoyed so-called pop psychology and spirituality books ever since I discovered Families and How to Survive Them by John Cleese and Robin Skynner in the 1980s, and Depression: The Way out of Your Prison by Dorothy Rowe at around the same time.

The Cleese book is a bit dated now, but Rowe’s set me off on a road that I am still following. She is what you might call a non-conforming Buddhist who introduced me to the writing of Alan Watts ( another non-conformer) whose The Meaning of Happiness and The Book have informed my life and worldview ever since.

The irony is that books of this particular stripe point you in a direction almost the opposite of most self-help books. Because, from How to Win Friends and Influence People through to The Power of Positive Thinking and Who Moved My Cheese?, “positive thinking” seems to be the unifying principle (although now partially supplanted by “mindfulness”).

The books I draw sustenance from contain the opposite wisdom. This isn’t negativity. It’s acceptance. Such thinking does not at first glance point you towards the destination of a happier life, which is probably why such tomes are far less popular than their bestselling peers. Yet these counter self-help books have a remarkable amount in common.

Most of them have Buddhism or Stoicism underpinning their thoughts. And they offer a different, and perhaps harder, road to happiness: not through effort, or willpower, or struggle with yourself, but through the forthright facing of facts that most of us prefer not to accept or think about.

Whether Seneca, or Nietzsche, Viktor Frankl or Rowe, Watts or Oliver Burkeman (The Antidote), or most recently Jordan B Peterson (12 Rules for Life), these thinkers all say much the same thing. Stop pretending. Get real.

It is not easy advice. Reality – now as ever – is unpopular, and for good reason. But the great thing about these self-help books is that, while giving sound advice, they are clear-eyed in acknowledging the truth: that happiness is not a given for anyone, there is no magic way of getting “it” – and that, crucially, pursuing it (or even believing in it), is one of the biggest obstacles to actually receiving it.

Such writers suggest the radical path to happiness comes from recognising the inevitability of unhappiness that comes as a result of the human birthright, that is, randomness, mortality, transitoriness, uncertainty and injustice. In other words, all the things we naturally shy away from and spend a huge amount of time and painful mental effort denying or trying not to think about.

Peterson perhaps puts it too strongly to say “life is catastrophe”, and the Buddha is out of date with “life is suffering”. Such strong medicine is understandably hard to take for many people in the comfortable and pleasure-seeking west. And despite what both Peterson and the Buddha say, not everyone suffers all that much.

Some people are just born happy or are lucky, or both, and are either incapable of feeling, or fortunate enough to never to have felt, a great deal in the way of pain or trauma. They are the people who never buy self-help books. But such individuals, I would suggest (although I can’t prove it), are the exception rather than the rule. The rest of us are simply pretending, to ourselves and to others, in order not to feel like failures.

But unhappiness is not failure. It is not pessimistic or morbid to say, for most of us, that life can be hard and that conflict is intrinsic to being and that mortality shadows our waking hours.

In fact it is life-affirming – because once you stop displacing these fears into everyday neuroses, life becomes tranquil, even when it is painful. And during those difficult times of loss and pain, to assert “this is the mixed package called life, and I embrace it in all its positive and negative aspects” shows real courage, rather than hiding in flickering, insubstantial fantasies of control, mysticism, virtue or wishful thinking.

That, as Dorothy Rowe says, is the real secret – that there is no secret.

Wednesday, 21 November 2012

School reports: the 15 best school reports submitted to the Telegraph

“The improvement in his handwriting has revealed his inability to spell.”

“Give him the job and he will finish the tools.”

“Rugby: Hobbs has useful speed when he runs in the right direction.”

“French is a foreign language to Fowler.”

“The stick and carrot must be very much in evidence before this particular donkey decides to exert itself.”

“He has given me a new definition of stoicism: he grins and I bear it.”

“At least his education hasn’t gone to his head.”

“Would be lazy but for absence.”

“The tropical forests are safe when John enters the woodwork room, for his projects are small and progress is slow.

“Henry Ford once said history is bunk. Yours most certainly is.”

“For this pupil all ages are dark.”

“He has an overdeveloped unawareness.”

“This boy does not need a Scripture teacher. He needs a missionary.”

“About as energetic as an absentee miner.”

“Unlike the poor, Graham is seldom with us.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)