'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label corporation. Show all posts

Showing posts with label corporation. Show all posts

Friday, 25 February 2022

Tuesday, 8 December 2020

Milton Friedman was wrong on the corporation

The doctrine that has guided economists and businesses for 50 years needs re-evaluation writes MARTIN WOLF in The FT

What should be the goal of the business corporation? For a long time, the prevailing view in English-speaking countries and, increasingly, elsewhere was that advanced by the economist Milton Friedman in a New York Times article, “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase Its Profits”, published in September 1970. I used to believe this, too. I was wrong.

What should be the goal of the business corporation? For a long time, the prevailing view in English-speaking countries and, increasingly, elsewhere was that advanced by the economist Milton Friedman in a New York Times article, “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase Its Profits”, published in September 1970. I used to believe this, too. I was wrong.

The article deserves to be read in full. But its kernel is in its conclusion: “there is one and only one social responsibility of business — to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.” The implications of this position are simple and clear. That is its principal virtue. But, as H L Mencken is supposed to have said (though may not have done), “for every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong”. This is a powerful example of that truth.

After 50 years, the doctrine needs re-evaluation. Suitably, given Friedman’s connection with the University of Chicago, the Stigler Center at its Booth School of Business has just published an ebook, Milton Friedman 50 Years Later, containing diverse views. In an excellent concluding article, Luigi Zingales, who promoted the debate, tries to give a balanced assessment. Yet, in my view, his analysis is devastating. He asks a simple question: “Under what conditions is it socially efficient for managers to focus only on maximising shareholder value?”

His answer is threefold: “First, companies should operate in a competitive environment, which I will define as firms being both price- and rule-takers. Second, there should not be externalities (or the government should be able to address perfectly these externalities through regulation and taxation). Third, contracts are complete, in the sense that we can specify in a contract all relevant contingencies at no cost.”

Needless to say, none of these conditions holds. Indeed, the existence of the corporation shows that they do not hold. The invention of the corporation allowed the creation of huge entities, in order to exploit economies of scale. Given their scale, the notion of businesses as price-takers is absurd. Externalities, some of them global, are evidently pervasive. Corporations also exist because contracts are incomplete. If it were possible to write contracts that specified every eventuality, the ability of management to respond to the unexpected would be redundant. Above all, corporations are not rule-takers but rather rulemakers. They play games whose rules they have a big role in creating, via politics.

My contribution to the ebook emphasises this last point by asking what a good “game” would look like. “It is one”, I argue, “in which companies would not promote junk science on climate and the environment; it is one in which companies would not kill hundreds of thousands of people, by promoting addiction to opiates; it is one in which companies would not lobby for tax systems that let them park vast proportions of their profits in tax havens; it is one in which the financial sector would not lobby for the inadequate capitalisation that causes huge crises; it is one in which copyright would not be extended and extended and extended; it is one in which companies would not seek to neuter an effective competition policy; it is one in which companies would not lobby hard against efforts to limit the adverse social consequences of precarious work; and so on and so forth.”

It is true, as many authors in this compendium argue, that the limited liability business corporation was (and is) a brilliant institutional innovation. It is true, too, that making corporate objectives more complex is likely to be problematic. So when Steve Kaplan of the Booth School asks how corporations should trade off many different goals, I have sympathy. Similarly, when business leaders tell us they are now going to serve the wider needs of society, I ask: first, do I believe they will do so; second, do I believe they know how to do so; and, last, who elected them to do so?

Yet the problems with the grossly unbalanced economic, social and political power inherent in the current situation are vast. On this, the contribution of Anat Admati of Stanford University is compelling. She notes that corporations have obtained a host of political and civil rights but lack corresponding obligations. Among other things, people are rarely held criminally liable for corporate crimes. Purdue Pharma, now in bankruptcy, pleaded guilty to criminal charges for its handling of the painkiller OxyContin, which addicted vast numbers of people. Individuals are routinely imprisoned for dealing illegal drugs, but as she points out “no individual within Purdue want to jail”.

Not least, unbridled corporate power has been a factor behind the rise of populism, especially rightwing populism. Consider how one goes about persuading people to accept Friedman’s libertarian economic ideas. In a universal-suffrage democracy, it is really difficult. To win, libertarians have had to ally themselves with ancillary causes — culture wars, racism, misogyny, nativism, xenophobia and nationalism. Much of this has of course been sotto voce and so plausibly deniable.

The 2008 financial crisis, and the subsequent bailout of those whose behaviour caused it, made selling a deregulated free-market even harder. So, it became politically essential for libertarians to double down on those ancillary causes. Mr Trump was not the person they wanted: he was erratic and unprincipled, but he was the political entrepreneur best suited to winning the presidency. He has given them what they most wanted: tax cuts and deregulation.

There are many arguments to be had over how corporations should change. But the biggest issue by far is how to create good rules of the game on competition, labour, the environment, taxation and so forth. Friedman assumed either that none of this mattered or that a working democracy would survive prolonged attack by people who thought as he did. Neither assumption proved correct. The challenge is to create good rules of the game, via politics. Today, we cannot.

Wednesday, 21 December 2016

Celebrity isn’t just harmless fun – it’s the smiling face of the corporate machine

Our failure to understand the link between fame and big business made the rise of Trump inevitable

George Monbiot in The Guardian

‘It is pointless to ask what Kim Kardashian does to earn her living: her role is to exist in our minds’. Photograph: Eduardo Munoz/Reuters

‘It is pointless to ask what Kim Kardashian does to earn her living: her role is to exist in our minds’. Photograph: Eduardo Munoz/Reuters

George Monbiot in The Guardian

‘It is pointless to ask what Kim Kardashian does to earn her living: her role is to exist in our minds’. Photograph: Eduardo Munoz/Reuters

‘It is pointless to ask what Kim Kardashian does to earn her living: her role is to exist in our minds’. Photograph: Eduardo Munoz/Reuters

Now that a reality TV star is preparing to become president of the United States, can we agree that celebrity culture is more than just harmless fun – that it might, in fact, be an essential component of the systems that govern our lives?

The rise of celebrity culture did not happen by itself. It has long been cultivated by advertisers, marketers and the media. And it has a function. The more distant and impersonal corporations become, the more they rely on other people’s faces to connect them to their customers.

Corporation means body; capital means head. But corporate capital has neither head nor body. It is hard for people to attach themselves to a homogenised franchise owned by a hedge fund whose corporate identity consists of a filing cabinet in Panama City. So the machine needs a mask. It must wear the face of someone we see as often as we see our next-door neighbours. It is pointless to ask what Kim Kardashian does to earn her living: her role is to exist in our minds. By playing our virtual neighbour, she induces a click of recognition on behalf of whatever grey monolith sits behind her this week.

An obsession with celebrity does not lie quietly beside the other things we value; it takes their place. A study published in the journal Cyberpsychology reveals that an extraordinary shift appears to have taken place between 1997 and 2007 in the US. In 1997, the dominant values (as judged by an adult audience) expressed by the shows most popular among nine- to 11 year-olds were community feeling, followed by benevolence. Fame came 15th out of the 16 values tested. By 2007, when shows such as Hannah Montana prevailed, fame came first, followed by achievement, image, popularity and financial success. Community feeling had fallen to 11th, benevolence to 12th.

A paper in the International Journal of Cultural Studies found that, among the people it surveyed in the UK, those who follow celebrity gossip most closely are three times less likely than people interested in other forms of news to be involved in local organisations, and half as likely to volunteer. Virtual neighbours replace real ones.

The blander and more homogenised the product, the more distinctive the mask it needs to wear. This is why Iggy Pop was used to promote motor insurance and Benicio del Toro is used to sell Heineken. The role of such people is to suggest that there is something more exciting behind the logo than office blocks and spreadsheets. They transfer their edginess to the company they represent. As soon they take the cheque that buys their identity, they become as processed and meaningless as the item they are promoting.

The celebrities you see most often are the most lucrative products, extruded through a willing media by a marketing industry whose power no one seeks to check. This is why actors and models now receive such disproportionate attention, capturing much of the space once occupied by people with their own ideas: their expertise lies in channelling other people’s visions.

A database search by the anthropologist Grant McCracken reveals that in the US actors received 17% of the cultural attention accorded to famous people between 1900 and 1910: slightly less than physicists, chemists and biologists combined. Film directors received 6% and writers 11%. Between 1900 and 1950, actors had 24% of the coverage, and writers 9%. By 2010, actors accounted for 37% (over four times the attention natural scientists received), while the proportion allocated to both film directors and writers fell to 3%.

You don’t have to read or watch many interviews to see that the principal qualities now sought in a celebrity are vapidity, vacuity and physical beauty. They can be used as a blank screen on to which anything can be projected. With a few exceptions, those who have least to say are granted the greatest number of platforms on which to say it.

This helps to explain the mass delusion among young people that they have a reasonable chance of becoming famous. A survey of 16-year-olds in the UKrevealed that 54% of them intend to become celebrities.

As soon as celebrities forget their allotted role, the hounds of hell are let loose upon them. Lily Allen was the media’s darling when she was advertising John Lewis. Gary Lineker couldn’t put a foot wrong when he stuck to selling junk food to children. But when they expressed sympathy for refugees, they were torn to shreds. When you take the corporate shilling, you are supposed to stop thinking for yourself.

Celebrity has a second major role: as a weapon of mass distraction. The survey published in the IJCS I mentioned earlier also reveals that people who are the most interested in celebrity are the least engaged in politics, the least likely to protest and the least likely to vote. This appears to shatter the media’s frequent, self-justifying claim that celebrities connect us to public life.

The survey found that people fixated by celebrity watch the news on average as much as others do, but they appear to exist in a state of permanent diversion. If you want people to remain quiescent and unengaged, show them the faces of Taylor Swift, Shia LaBeouf and Cara Delevingne several times a day.

In Trump we see a perfect fusion of the two main uses of celebrity culture: corporate personification and mass distraction. His celebrity became a mask for his own chaotic, outsourced and unscrupulous business empire. His public image was the perfect inversion of everything he and his companies represent. As presenter of the US version of The Apprentice, this spoilt heir to humongous wealth became the face of enterprise and social mobility. During the presidential elections, his noisy persona distracted people from the intellectual void behind the mask, a void now filled by more lucid representatives of global capital.

Celebrities might inhabit your life, but they are not your friends. Regardless of the intentions of those on whom it is bequeathed, celebrity is the lieutenant of exploitation. Let’s turn our neighbours back into our neighbours, and turn our backs on those who impersonate them.

The rise of celebrity culture did not happen by itself. It has long been cultivated by advertisers, marketers and the media. And it has a function. The more distant and impersonal corporations become, the more they rely on other people’s faces to connect them to their customers.

Corporation means body; capital means head. But corporate capital has neither head nor body. It is hard for people to attach themselves to a homogenised franchise owned by a hedge fund whose corporate identity consists of a filing cabinet in Panama City. So the machine needs a mask. It must wear the face of someone we see as often as we see our next-door neighbours. It is pointless to ask what Kim Kardashian does to earn her living: her role is to exist in our minds. By playing our virtual neighbour, she induces a click of recognition on behalf of whatever grey monolith sits behind her this week.

An obsession with celebrity does not lie quietly beside the other things we value; it takes their place. A study published in the journal Cyberpsychology reveals that an extraordinary shift appears to have taken place between 1997 and 2007 in the US. In 1997, the dominant values (as judged by an adult audience) expressed by the shows most popular among nine- to 11 year-olds were community feeling, followed by benevolence. Fame came 15th out of the 16 values tested. By 2007, when shows such as Hannah Montana prevailed, fame came first, followed by achievement, image, popularity and financial success. Community feeling had fallen to 11th, benevolence to 12th.

A paper in the International Journal of Cultural Studies found that, among the people it surveyed in the UK, those who follow celebrity gossip most closely are three times less likely than people interested in other forms of news to be involved in local organisations, and half as likely to volunteer. Virtual neighbours replace real ones.

The blander and more homogenised the product, the more distinctive the mask it needs to wear. This is why Iggy Pop was used to promote motor insurance and Benicio del Toro is used to sell Heineken. The role of such people is to suggest that there is something more exciting behind the logo than office blocks and spreadsheets. They transfer their edginess to the company they represent. As soon they take the cheque that buys their identity, they become as processed and meaningless as the item they are promoting.

The celebrities you see most often are the most lucrative products, extruded through a willing media by a marketing industry whose power no one seeks to check. This is why actors and models now receive such disproportionate attention, capturing much of the space once occupied by people with their own ideas: their expertise lies in channelling other people’s visions.

A database search by the anthropologist Grant McCracken reveals that in the US actors received 17% of the cultural attention accorded to famous people between 1900 and 1910: slightly less than physicists, chemists and biologists combined. Film directors received 6% and writers 11%. Between 1900 and 1950, actors had 24% of the coverage, and writers 9%. By 2010, actors accounted for 37% (over four times the attention natural scientists received), while the proportion allocated to both film directors and writers fell to 3%.

You don’t have to read or watch many interviews to see that the principal qualities now sought in a celebrity are vapidity, vacuity and physical beauty. They can be used as a blank screen on to which anything can be projected. With a few exceptions, those who have least to say are granted the greatest number of platforms on which to say it.

This helps to explain the mass delusion among young people that they have a reasonable chance of becoming famous. A survey of 16-year-olds in the UKrevealed that 54% of them intend to become celebrities.

As soon as celebrities forget their allotted role, the hounds of hell are let loose upon them. Lily Allen was the media’s darling when she was advertising John Lewis. Gary Lineker couldn’t put a foot wrong when he stuck to selling junk food to children. But when they expressed sympathy for refugees, they were torn to shreds. When you take the corporate shilling, you are supposed to stop thinking for yourself.

Celebrity has a second major role: as a weapon of mass distraction. The survey published in the IJCS I mentioned earlier also reveals that people who are the most interested in celebrity are the least engaged in politics, the least likely to protest and the least likely to vote. This appears to shatter the media’s frequent, self-justifying claim that celebrities connect us to public life.

The survey found that people fixated by celebrity watch the news on average as much as others do, but they appear to exist in a state of permanent diversion. If you want people to remain quiescent and unengaged, show them the faces of Taylor Swift, Shia LaBeouf and Cara Delevingne several times a day.

In Trump we see a perfect fusion of the two main uses of celebrity culture: corporate personification and mass distraction. His celebrity became a mask for his own chaotic, outsourced and unscrupulous business empire. His public image was the perfect inversion of everything he and his companies represent. As presenter of the US version of The Apprentice, this spoilt heir to humongous wealth became the face of enterprise and social mobility. During the presidential elections, his noisy persona distracted people from the intellectual void behind the mask, a void now filled by more lucid representatives of global capital.

Celebrities might inhabit your life, but they are not your friends. Regardless of the intentions of those on whom it is bequeathed, celebrity is the lieutenant of exploitation. Let’s turn our neighbours back into our neighbours, and turn our backs on those who impersonate them.

Monday, 25 April 2016

TTIP is a very bad excuse to vote for Brexit

Nick Dearden in The Guardian

Barack Obama gave TTIP the hard sell, but leaving the EU would only make the controversial trade deal more likely – and possibly worse

‘In Berlin, 250,000 people took to the streets last October to protest about TTIP.’ Photograph: Axel Schmidt/Getty Images

Barack Obama’s key message to Europe’s leaders last week was “let’s speed up TTIP”. The US-EU trade deal, formally called the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, has been mired in controversy on both sides of the Atlantic. The “free trade” agenda has become poison in the US primaries, forcing even pro-trade Hillary Clinton to re-examine TTIP.

The next round of talks begin on Monday in New York and Obama is worried – unless serious progress is made in coming months, his trade legacy may be doomed. The problem for the US president is selling TTIP at the same time as trying to warn against the dangers of Brexit. This is a tough ask because TTIP has been a godsend for Brexit campaigners, who argue that the deal is a major reason to cut loose from Brussels.

It’s true that TTIP is a symbol of all that’s wrong with Europe: dreamed up by corporate lobbyists, TTIP is less about trade and more about giving big business sweeping new powers over our society. It is a blueprint for deregulation and privatisation. As such it makes a good case for Brexit.

Until you remember that the British government has done everything possible to push the most extreme version of TTIP, just as they’ve fought against pretty much every financial regulation, from bankers bonuses to a financial transaction tax. While Germany and France were concerned about TTIP’s corporate court system – which allows foreign business to sue governments for “unfair” laws like putting cigarettes in plain packets – the UK secretly wrote to the European commission president demanding he retain it.

At the heart of TTIP is a radical agenda of deregulation. The ambition is that everything from food standards to financial policies are “standardised” in the US and EU, with big business gaining new powers over the process. This could have been inspired by David Cameron’s own programme of stripping away laws that annoy big business, no matter how important they are for people and the environment.

Cameron’s policy means scrapping two laws for every one brought in and giving every regulatory body the duty to have regard to the desirability of “promoting economic growth”. That could include the equality and human rights commission and the health and safety executive. The TUC described Britain as “exporting their anti-worker position into Europe and it is spreading like a bad outbreak of gastric flu”.

Brexit wouldn’t necessarily stop TTIP anyway – that’s all down to the transition process. At the very least, Britain would need to adopt many of TTIP’s provisions in order to remain in the single market.

But it gets worse: every scenario for Brexit is premised on extreme free trade agreements coupled with looser regulation to make us more competitive. “Outcompeting” the EU through lower standards is the strategy. High-profile supporters of the Brexit campaign have repeatedly said that they believe the UK would be able to realise a more “ambitious” and faster free trade deal if we stood alone. There’s every reason to think that Brexit will turn the UK into a paradise for free market capitalism: a TTIP on steroids.

Barack Obama’s key message to Europe’s leaders last week was “let’s speed up TTIP”. The US-EU trade deal, formally called the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, has been mired in controversy on both sides of the Atlantic. The “free trade” agenda has become poison in the US primaries, forcing even pro-trade Hillary Clinton to re-examine TTIP.

The next round of talks begin on Monday in New York and Obama is worried – unless serious progress is made in coming months, his trade legacy may be doomed. The problem for the US president is selling TTIP at the same time as trying to warn against the dangers of Brexit. This is a tough ask because TTIP has been a godsend for Brexit campaigners, who argue that the deal is a major reason to cut loose from Brussels.

It’s true that TTIP is a symbol of all that’s wrong with Europe: dreamed up by corporate lobbyists, TTIP is less about trade and more about giving big business sweeping new powers over our society. It is a blueprint for deregulation and privatisation. As such it makes a good case for Brexit.

Until you remember that the British government has done everything possible to push the most extreme version of TTIP, just as they’ve fought against pretty much every financial regulation, from bankers bonuses to a financial transaction tax. While Germany and France were concerned about TTIP’s corporate court system – which allows foreign business to sue governments for “unfair” laws like putting cigarettes in plain packets – the UK secretly wrote to the European commission president demanding he retain it.

At the heart of TTIP is a radical agenda of deregulation. The ambition is that everything from food standards to financial policies are “standardised” in the US and EU, with big business gaining new powers over the process. This could have been inspired by David Cameron’s own programme of stripping away laws that annoy big business, no matter how important they are for people and the environment.

Cameron’s policy means scrapping two laws for every one brought in and giving every regulatory body the duty to have regard to the desirability of “promoting economic growth”. That could include the equality and human rights commission and the health and safety executive. The TUC described Britain as “exporting their anti-worker position into Europe and it is spreading like a bad outbreak of gastric flu”.

Brexit wouldn’t necessarily stop TTIP anyway – that’s all down to the transition process. At the very least, Britain would need to adopt many of TTIP’s provisions in order to remain in the single market.

But it gets worse: every scenario for Brexit is premised on extreme free trade agreements coupled with looser regulation to make us more competitive. “Outcompeting” the EU through lower standards is the strategy. High-profile supporters of the Brexit campaign have repeatedly said that they believe the UK would be able to realise a more “ambitious” and faster free trade deal if we stood alone. There’s every reason to think that Brexit will turn the UK into a paradise for free market capitalism: a TTIP on steroids.

-----

What is TTIP and why should we be angry about it?

--------

Is there any hope? Yes – the movement to defeat TTIP received the support of well over 3 million Europeans in a little over a year. In Berlin, 250,000 people took to the streets last October. The deal was meant to be signed by now – but together, Europe’s people have seriously stalled things. Would it really be possible to stop such a move if we couldn’t link up with campaigners across Europe? If being in the EU has brought us TTIP, it has also brought us the means to stop it.

Europe also allows the potential to take on the corporate power which TTIP symbolises: the biggest threat to our sovereignty. Even in the best of circumstances, there is only so much a small nation state can do against the size and power of global big business. But through being in Europe we could stop tax avoidance, introduce a financial transactions tax, hold corporations legally responsible for their human rights abuses, enforce world-leading climate targets, develop new forms of public ownership of key resources. At least, we could if Britain stopped standing in the way.

Obama’s rationale for avoiding Brexit is quite different. The US establishment has always been interested in Britain’s role as a fifth column in Europe, undermining a social Europe on behalf of global (read US) corporations. Reclaiming our sovereignty means not playing this role, and instead working with those in Europe who want to build a different world. Another Europe is possible.

What is TTIP and why should we be angry about it?

--------

Is there any hope? Yes – the movement to defeat TTIP received the support of well over 3 million Europeans in a little over a year. In Berlin, 250,000 people took to the streets last October. The deal was meant to be signed by now – but together, Europe’s people have seriously stalled things. Would it really be possible to stop such a move if we couldn’t link up with campaigners across Europe? If being in the EU has brought us TTIP, it has also brought us the means to stop it.

Europe also allows the potential to take on the corporate power which TTIP symbolises: the biggest threat to our sovereignty. Even in the best of circumstances, there is only so much a small nation state can do against the size and power of global big business. But through being in Europe we could stop tax avoidance, introduce a financial transactions tax, hold corporations legally responsible for their human rights abuses, enforce world-leading climate targets, develop new forms of public ownership of key resources. At least, we could if Britain stopped standing in the way.

Obama’s rationale for avoiding Brexit is quite different. The US establishment has always been interested in Britain’s role as a fifth column in Europe, undermining a social Europe on behalf of global (read US) corporations. Reclaiming our sovereignty means not playing this role, and instead working with those in Europe who want to build a different world. Another Europe is possible.

Sunday, 27 March 2016

The Death of Democracy - Say no to Free Trade Agreements

David Malone on why TTIP (free trade agreements) are anti-democratic and against the people.

Tuesday, 8 April 2014

How have these corporations colonised our public life?

Our politicians have delegated power to global giants engineering a world of conformity and consumerism

One of Unilever's ‘real women' series of advertisements for Dove. Photograph: PA

How do you engineer a bland, depoliticised world, a consensus built around consumption and endless growth, a dream world of materialism and debt and atomisation, in which all relations can be prefixed with a dollar sign, in which we cease to fight for change? You delegate your powers to companies whose profits depend on this model.

Power is shifting: to places in which we have no voice or vote. Domestic policies are forged by special advisers and spin doctors, by panels and advisory committees stuffed with lobbyists. The self-hating state withdraws its own authority to regulate and direct. Simultaneously, the democratic vacuum at the heart of global governance is being filled, without anything resembling consent, by international bureaucrats and corporate executives. The NGOs permitted – often as an afterthought – to join them intelligibly represent neither civil society nor electorates. (And please spare me that guff about consumer democracy or shareholder democracy: in both cases some people have more votes than others, and those with the most votes are the least inclined to press for change.)

To me, the giant consumer goods company Unilever, with which I clashed over the issue of palm oil a few days ago, symbolises these shifting relationships. I can think of no entity that has done more to blur the lines between the role of the private sector and the role of the public sector. If you blotted out its name while reading its web pages, you could mistake it for an agency of the United Nations.

It seems to have representation almost everywhere. Its people inhabit (to name a few) the British government's Ecosystem Markets Task Force and Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, the G8'sNew Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition, the World Food Programme, the Global Green Growth Forum, the UN's Scaling Up Nutrition programme, its Sustainable Development Solutions Network, Global Compact and the UN High Level Panel on global development.

Sometimes Unilever uses this power well. Its efforts to reduce its own use of energy and water and its production of waste, and to project these changes beyond its own walls,look credible and impressive. Sometimes its initiatives look to me like self-serving bullshit.

Its "Dove self-esteem project", for instance, claims to be "helping millions of young people to improve their self-esteem through educational programmes". One of its educational videos maintains that beauty "couldn't be more critical to your happiness", which is surely the belief that trashes young people's self-esteem in the first place. But of course you can recover it by plastering yourself with Dove-branded gloop: Unilever reports that 82% of women in Canada who are aware of its project "would be more likely to purchase Dove".

Sometimes it seems to play both ends of the game. For instance, it says it is reducing the amount of salt and fat and sugar in its processed foods. But it also hosted and chaired, before the last election, the Conservative party's public health commission, which was seen by health campaigners as an excuse for avoiding effective action on obesity, poor diets and alcohol abuse. This body helped to purge government policy of such threats as further advertising restrictions and the compulsory traffic-light labelling of sugar, salt and fat.

The commission then produced a "responsibility deal" between government and business, on the organising board of which Unilever still sits. Under this deal, the usual relationship between lobbyists and government is reversed. The corporations draft government policy, which is then sent to civil servants for comment. Regulation is replaced by voluntarism. The Guardian has named Unilever as one of the companies that refused to sign the deal's voluntary pledge on calorie reduction.

This is not to suggest that everything these panels and alliances and boards and forums propose is damaging. But as the development writer Lou Pingeot points out, their analysis of the world's problems is partial and self-serving, casting corporations as the saviours of the world's people but never mentioning their role in causing many of the problems (such as financial crisis, land-grabbing, tax loss, obesity, malnutrition, climate change, habitat destruction, poverty, insecurity) they claim to address. Most of their proposed solutions either require passivity from governments (poverty will be solved by wealth trickling down through a growing economy) or the creation of a more friendly environment for business.

At best, these corporate-dominated panels are mostly useless: preening sessions in which chief executives exercise messiah complexes. At their worst, they are a means by which global companies reshape politics in their own interests, universalising – in the name of conquering want and exploitation – their exploitative business practices.

Almost every political agent – including some of the NGOs that once opposed them – is in danger of being loved to death by these companies. In February the Guardian signed a seven-figure deal with Unilever, which, the publisher claimed, is "centred on the shared values of sustainable living and open storytelling". The deal launched an initiative called Guardian Labs, which will help brands find "more engaging ways to tell their story". The Guardian points out that it has guidelines covering such sponsorship deals to ensure editorial independence.

I recognise and regret the fact that all newspapers depend for their survival on corporate money (advertising and sponsorship probably account, in most cases, for about 70% of their income). But this, to me, looks like another step down the primrose path. As the environmental campaigner Peter Gerhardt puts it, companies like Unilever "try to stakeholderise every conflict". By this, I think, he means that they embrace their critics, involving them in a dialogue that is open in the sense that a lobster pot is open, breaking down critical distance and identity until no one knows who they are any more.

Yes, I would prefer that companies were like Unilever rather than Goldman Sachs, Cargill or Exxon, in that it seems to have a keen sense of what a responsible company should do, even if it doesn't always do it. But it would be better still if governments and global bodies stopped delegating their powers to corporations. They do not represent us and they have no right to run our lives.

Tuesday, 11 March 2014

Give and take in the EU-US trade deal? Sure. We give, the corporations take

I have three challenges for the architects of a proposed transatlantic trade deal. If they reject them, they reject democracy

Illustration by Daniel Pudles

Nothing threatens democracy as much as corporate power. Nowhere do corporations operate with greater freedom than between nations, for here there is no competition. With the exception of the European parliament, there is no transnational democracy, anywhere. All other supranational bodies – the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the United Nations, trade organisations and the rest – work on the principle of photocopy democracy (presumed consent is transferred, copy by copy, to ever-greyer and more remote institutions) or no democracy at all.

When everything has been globalised except our consent, corporations fill the void. In a system that governments have shown no interest in reforming, global power is often scarcely distinguishable from corporate power. It is exercised through backroom deals between bureaucrats and lobbyists.

This is how negotiations over the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership(TTIP) began. The TTIP is a proposed single market between the United States and the European Union, described as "the biggest trade deal in the world". Corporate lobbyists secretly boasted that they would "essentially co-write regulation". But, after some of their plans were leaked and people responded with outrage, democracy campaigners have begun to extract a few concessions. The talks have just resumed, and there's a sense that we cannot remain shut out.

This trade deal has little to do with removing trade taxes (tariffs). As the EU's chief negotiator says, about 80% of it involves "discussions on regulations which protect people from risks to their health, safety, environment, financial and data security". Discussions on regulations means aligning the rules in the EU with those in the US. But Karel De Gucht, the European trade commissioner, maintains that European standards "are not up for negotiation. There is no 'give and take'." An international treaty without give and take? That is a novel concept. A treaty with the US without negotiation? That's not just novel, that's nuts.

You cannot align regulations on both sides of the Atlantic without negotiation. The idea that the rules governing the relationship between business, citizens and the natural world will be negotiated upwards, ensuring that the strongest protections anywhere in the trading bloc will be applied universally, is simply not credible when governments on both sides of the Atlantic have promised to shred what they dismissively call red tape. There will be negotiation. There will be give and take. The result is that regulations are likely to be levelled down. To believe otherwise is to live in fairyland.

Last month, the Financial Times reported that the US is using these negotiations "to push for a fundamental change in the way business regulations are drafted in the EU to allow business groups greater input earlier in the process". At first, De Gucht said that this was "impossible". Then he said he is "ready to work in that direction". So much for no give and take.

But this is not all that democracy must give so that corporations can take. The most dangerous aspect of the talks is the insistence on both sides on a mechanism called investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS). ISDS allows corporations to sue governments at offshore arbitration panels of corporate lawyers, bypassing domestic courts. Inserted into other trade treaties, it has been used by big business to strike down laws that impinge on its profits: the plain packaging of cigarettes; tougher financial rules; stronger standards on water pollution and public health; attempts to leave fossil fuels in the ground.

At first, De Gucht told us there was nothing to see here. But in January the man who doesn't do give and take performed a handbrake turn and promised that there would be a three-month public consultation on ISDS, beginning in "early March". The transatlantic talks resumed on Monday. So far there's no sign of the consultation.

And still there remains that howling absence: a credible explanation of why ISDS is necessary. As Kenneth Clarke, the British minister promoting the TTIP, admits: "It was designed to support businesses investing in countries where the rule of law is unpredictable, to say the least." So what is it doing in a US-EU treaty? A report commissioned by the UK government found that ISDS "is highly unlikely to encourage investment" and is "likely to provide the UK with few or no benefits". But it could allow corporations on both sides of the ocean to sue the living daylights out of governments that stand in their way.

Unlike Karel De Gucht, I believe in give and take. So instead of rejecting the whole idea, here are some basic tests which would determine whether or not the negotiators give a fig about democracy.

First, all negotiating positions, on both sides, would be released to the public as soon as they are tabled. Then, instead of being treated like patronised morons, we could debate these positions and consider their impacts.

Second, every chapter of the agreement would be subject to a separate vote in the European parliament. At present the parliament will be invited only to adopt or reject the whole package: when faced with such complexity, that's a meaningless choice.

Third, the TTIP would contain a sunset clause. After five years it would be reconsidered. If it has failed to live up to its promise of enhanced economic performance, or if it reduces public safety or public welfare, it could then be scrapped. I accept that this would be almost unprecedented: most such treaties, unlike elected governments, are "valid indefinitely". How democratic does that sound?

So here's my challenge to Mr De Gucht and Mr Clarke and the others who want us to shut up and take our medicine: why not make these changes? If you reject them, how does that square with your claims about safeguarding democracy and the public interest? How about a little give and take?

Tuesday, 16 July 2013

Cigarette packaging: the corporate smokescreen

Noble sentiments about individual liberty are being used to bend democracy to the will of the tobacco industry

BETA

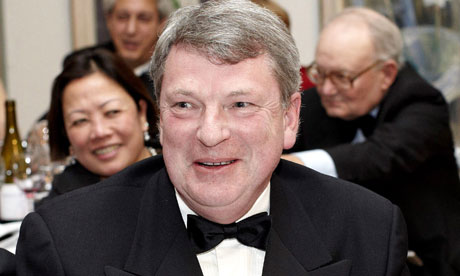

'Lynton Crosby personifies the new dispensation, in which men and women glide between corporations and politics, and appear to act as agents for big business within government.' Photograph: David Hartley / Rex Features

It's a victory for the hidden persuaders, the astroturfers, sock puppets, purchased scholars and corporate moles. On Friday the government announced that it will not oblige tobacco companies to sell cigarettes in plain packaging. How did it happen? The public was overwhelmingly in favour. The evidence that plain packets will discourage young people from smoking is powerful. But it fell victim to a lobbying campaign that was anything but plainly packaged.

Tobacco companies are not allowed to advertise their products. Nor, as they are so unpopular, can they appeal directly to the public. So they spend their cash on astroturfing(fake grassroots campaigns) and front groups. There is plenty of money to be made by people unscrupulous enough to take it.

Much of the anger about this decision has been focused on Lynton Crosby. Crosby is David Cameron's election co-ordinator. He also runs a lobbying company that works for the cigarette firms Philip Morris and British American Tobacco. He personifies the new dispensation, in which men and women glide between corporations and politics, and appear to act as agents for big business within government. The purpose of today's technocratic politics is to make democracy safe for corporations: to go through the motions of democratic consent while reshaping the nation at their behest.

But even if Crosby is sacked, the infrastructure of hidden persuasion will remain intact. Nor will it be affected by the register of lobbyists that David Cameron will announce on Tuesday, antiquated before it is launched.

Nanny state, health police, red tape, big government: these terms have been devised or popularised by corporate front groups. The companies who fund them are often ones that cause serious harm to human welfare. The front groups campaign not only against specific regulations, but also against the very principle of the democratic restraint of business.

I see the "free market thinktanks" as the most useful of these groups. Their purpose, I believe, is to invest corporate lobbying with authority. Mark Littlewood, the head of one of these thinktanks – the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) – has described plain packaging as "the latest ludicrous move in the unending, ceaseless, bullying war against those who choose to produce and consume tobacco". Over the past few days he's been in the media repeatedly, railing against the policy. So do the IEA's obsessions just happen to coincide with those of the cigarette firms? The IEA refuses to say who its sponsors are and how much they pay. But as a result of persistent digging, we now know that British American Tobacco, Philip Morris and Japan Tobacco International have been funding the institute – in BAT's case since 1963. British American Tobacco has admitted that it gave the institute £20,000 last year and that it's "planning to increase our contribution in 2013 and 2014".

Otherwise it's a void. The IEA tells me, "We do not accept any earmarked money for commissioned research work from any company." Really? But whether companies pay for specific publications or whether they continue to fund a body that – by the purest serendipity – publishes books and pamphlets that concur with the desires of its sponsors, surely makes no difference.

The institute has almost unrivalled access to the BBC and other media, where it promotes the corporate agenda without ever being asked to disclose its interests. Because they remain hidden, it retains a credibility its corporate funders lack. Amazingly, since 2011 Mark Littlewood has also been the government's adviser on cutting the regulations that business doesn't like. Corporate conflicts of interest intrude into the heart of this country's political life.

In 2002, a letter sent by the philosopher Roger Scruton to Japan Tobacco International (which manufactures Camel, Winston and Silk Cut) was leaked. In the letter, Professor Scruton complained that the £4,500 a month JTI was secretly paying him to place pro-tobacco articles in newspapers was insufficient: could they please raise it to £5,500?

Scruton was also working for the Institute of Economic Affairs, through which he published a major report attacking the World Health Organisation for trying to regulate tobacco. When his secret sponsorship was revealed, the IEA pronounced itself shocked: shocked to find that tobacco funding is going on in here. It claimed that "in the past we have relied on our authors to come forward with any competing interests, but that is going to change ... we are developing a policy to ensure it doesn't happen again." Oh yes? Eleven years later I have yet to find a declaration in any IEA publication that the institute (let alone the author) has been taking money from companies with an interest in its contents.

The IEA is one of several groups that appear to be used as a political battering ram by tobacco companies. On the TobaccoTactics website you can find similarly gruesome details about the financial interests and lobbying activities of, for example, the Adam Smith Institute and the Common Sense Alliance.

Even where tobacco funding is acknowledged, only half the story is told. Forest, a group that admits that "most of our money is donated by UK-based tobacco companies", has spawned a campaign against plain packaging called Hands Off Our Packs. The Department of Health has published some remarkable documents, alleging the blatant rigging of signatures on a petition launched by this campaign. Hands Off Our Packs is run by Angela Harbutt. She lives with Mark Littlewood.

Libertarianism in the hands of these people is a racket. All those noble sentiments about individual liberty, limited government and economic freedom are nothing but a smokescreen, a disguised form of corporate advertising. Whether Mark Littlewood, Lynton Crosby or David Cameron articulate it, it means the same thing: ideological cover for the corporations and the very rich.

Arguing against plain packaging on the Today programme, Mark Field MP, who came across as the transcendental form of an amoral, bumbling Tory twit, recited the usual tobacco company talking points, with their usual disingenuous disclaimers. In doing so, he made a magnificent slip of the tongue. "We don't want to encourage young people to take up advertising ... er, er, to take up tobacco smoking." He got it right the first time.

Wednesday, 10 July 2013

In today's corporations the buck never stops. Welcome to the age of irresponsibility

Our largest companies have become so complex that no one's expected to fully know what's going on. Yet the rewards are bigger than ever

Hon Ha's Foxconn plant in Shenzhen, China, in 2010. That year there were 12 suicides in the 300,000-strong workforce. 'The top managers of Apple escaped blame because these deaths happened in factories in another country (China) owned by a company from yet another country (Hon Hai, the Taiwanese multinational).' Photograph: Qilai Shen

George Osborne confirmed on Monday that he would accept the recommendation of Britain's parliamentary commission on banking standards and add to his banking reform bill a new offence of "reckless misconduct in the management of a bank".

That is a bit of a setback for the managerial class, but it still does not sufficiently change the overall picture that it is a great time to be a top manager in the corporate world, especially in the US and Britain.

Not only do they give you a good salary and handsome bonus, but they are really understanding when you fail to live up to expectations. If they want to show you the door in the middle of your term, they will give you millions of dollars, even tens of millions, in "termination payment". Even if you have totally screwed up, the worst that can happen is that they take away your knighthood or make you give up, say, a third of your multimillion-pound pension pot.

Even better, the buck never stops at your desk. It usually stops at the lowest guy in the food chain – a rogue trader or some owner of a two-bit factory in Bangladesh. Occasionally you may have to blame your main supplier, but rarely your own company, and never yourself.

Welcome to the age of irresponsibility.

The largest companies today are so complex that top managers are not even expected to know fully what is really going on in them. These companies have also increasingly outsourced activities to multiple layers of subcontractors in supply chains crisscrossing the globe.

Increasing complexity not only lowers the quality of decisions, as it creates an information overload, but makes it more difficult to pin down responsibilities. A number of recent scandals have brought home this reality.

The multiple suicides of workers in Foxconn factories in China have revealed Victorian labour conditions down the supply chains for the most futuristic Apple products. But the top managers of Apple escaped blame because these deaths happened in factories in another country (China) owned by a company from yet another country (Hon Hai, the Taiwanese multinational).

No one at the top of the big supermarkets took serious responsibility in the horsemeat scandal because, it was accepted, they could not be expected to police supply chains running from Romania through the Netherlands, Cyprus and Luxembourg to France (and that is only one of several chains involved).

The problem is even more serious in the financial sector, which these days deals in assets that involve households (in the case of mortgages), companies and governments all over the world. On top of that these financial assets are combined, sliced and diced many times over, to produce highly complicated "derivative" products. The result is an exponential increase in complexity.

Andy Haldane, executive director of financial stability at the Bank of England, once pointed out that in order to fully understand a CDO2 – one of the more complicated financial derivatives (but not the most complicated) – a prospective investor needs to absorb more than a billion pages of information. I have come across bankers who confessed that they had derivative contracts running to a few hundred pages, which they naturally didn't have time to read.

Given this level of complexity, financial companies have come to rely heavily on countless others – stock analysts, financial journalists, credit-rating agencies, you name it – for information and, more importantly, making judgments. This means that when something goes wrong, they can always blame others: poor people in Florida who bought houses they cannot afford; "irresponsible" foreign governments; misleading foreign stock analysts; and, yes, incompetent credit-rating agencies.

The result is an economic system in which no one in "responsible" positions takes any serious responsibility. Unless radical action is taken, we will see many more financial crises and corporate scandals in the years to come.

The first thing we need is to modernise our sense of crime and punishment. Most of us still instinctively subscribe to the primeval notion of crime as a direct physical act – killing someone, stealing silver. But in the modern economy, with a complex division of labour, indirect non-physical acts can also seriously harm people. If misbehaving financiers and incompetent regulators cause an economic crisis, they can indirectly kill people by subjecting them to unemployment-related stress and by reducing public health expenditure, as shown by books like The Body Politic. We need to accept the seriousness of these "long-distance crimes" and strengthen punishments for them.

More importantly, we need to simplify our economic system so that responsibilities are easier to determine. This is not to say we have to go back to the days of small workshops owned by a single capitalist: increased complexity is inevitable if we are to increase productivity. However, much of the recent rise in complexity has been designed to make money for certain people, at the cost of social productivity. Such socially unproductive complexity needs to be reduced.

Financial derivatives are the most obvious examples. Given their potential to exponentially increase the complexity of the financial system – and thus the degree of irresponsibility within it – we should only allow such products when their creators can prove their productivity and safety, similar to how the drug approval process works.

The negative potential of outsourcing in non-financial industries may not be as great as that of financial derivatives, but the buying companies should be made far more accountable for making their subcontractors comply with rules regarding product safety, working conditions and environmental standards.

Without measures to simplify the system and recalibrate our sense of crime and punishment, the age of irresponsibility will destroy us all.

Friday, 15 February 2013

Big UK tax avoiders will easily get round new government policy

These new proposals to beat tax avoidance won't work, as they expect opaque corporations to come clean

'Starbucks, Google, Amazon, Microsoft and others can continue to route transactions through offshore subsidiaries and suck out profits through loans, royalties and management fee programmes and thus reduce their taxable profits in the UK.' Photograph: Kerim Okten/EPA

The UK government has finally responded to public anger about organised tax avoidance. The key policy is that from April 2013, potential suppliers to central government for contracts of £2m or more will have to declare whether they indulged in tax avoidance. Those with a history of indulgence in aggressive tax avoidance schemes during the previous 10 years, as evidenced by negative tax tribunal decisions and court cases, could be barred from contracts. Their existing contracts could also be terminated. The policy is high on gimmicks and empty gestures, and short on substance.

The proposed policy only applies to bidders for central government contracts. Thus tax avoiders can continue to make profits from local government, government agencies and other government-funded organisations – including universities, hospitals, schools and public bodies. Banks, railway companies, gas, electricity, water, steel, biotechnology, motor vehicle and arms companies receive taxpayer-funded loans, guarantees and subsidies, but their addiction to tax avoidance will not be touched by the proposed policy.

The policy will apply to one bidder, or a company, at a time and not to all members of a group of companies even though they will share the profits. Thus, one subsidiary in a group can secure a government contract by claiming to be clean, while other affiliates and subsidiaries can continue to rob the public purse through tax avoidance. There is nothing to prevent a company from forming another subsidiary for the sole purpose of bidding for a contract while continuing with nefarious practices elsewhere.

Starbucks, Google, Amazon, Microsoft and others can continue to route transactions through offshore subsidiaries and suck out profits through loans, royalties and management fee programmes and thus reduce their taxable profits in the UK. Such strategies are not covered by the government policy and these companies can continue to receive taxpayer-funded contracts.

The policy will not apply to the tax avoidance industry, consisting of accountants, lawyers and finance experts devising new dodges. Earlier this week, a US court declared that an avoidance scheme jointly developed and marketed by UK-based Barclays Bank and accountancy firm KPMG was unlawful. The scheme, codenamed Stars – or Structured Trust Advantaged Repackaged Securities – enabled its participants to manufacture artificial tax credits on loans. This scheme was sold to the US-based Bank of New York Mellon (BNYM). The US tax authorities launched a test case and a court rejected BNYM's claim for tax credits of $900m. The presiding judge said that that avoidance scheme "was an elaborate series of pre-arranged steps designed as a subterfuge for generating, monetising and transferring the value of foreign tax credits among the Stars participants" (page 25). It "lacked economic substance" (page 53) and was a "sham" transaction (page 54). Whether equivalent schemes have been used by UK corporations is not yet known.

The above case highlights a number of issues. The UK-based organisations causing havoc in the US, Africa, Asia and elsewhere will not be restrained. They can still secure taxpayer-funded contracts in the UK. Now suppose that the Bank of New York Mellon scheme was applied by Barclays Bank to its own affairs and declared to be unlawful by a UK court. If so, possibly Barclays may be deterred from bidding for a central government contract, but there will be no penalties for KPMG as accountancy firms are not covered by the proposed rules.

The recent inquiry by the public accounts committee into the operations of PricewaterhouseCoopers, Deloitte, KPMG and Ernst & Young noted that the firms are the centre of a global tax avoidance industry. Even though a US court has declared one of these schemes to be unlawful, the UK government does not investigate them, close them, or recover legal costs of fighting the schemes devised by them. No accountancy firm has ever been disciplined by any professional accountancy body for peddling avoidance schemes, even when they have been shown to be unlawful. The firms continue to act as advisers to government departments, make profits from taxpayers through private finance initiative, information technology and consultancy contracts. There is clearly no business like accountancy business.

The proposed government policy will not work. It expects corporations who can construct opaque corporate structures and sham transactions to come clean. That will not happen. In addition, a government loth to invest in public regulation will not have the sufficient manpower to police any self-certifications by big business.

An effective policy should prevent tax avoiders and their advisers from making any profit from taxpayers. It should apply to all the players in the tax avoidance industry, regardless of whether their schemes are peddled at home or abroad.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)