It took corporate America a while to warm to Donald Trump. Some of his positions, especially on trade, horrified business leaders. Many of them favoured Ted Cruz or Scott Walker. But once Trump had secured the nomination, the big money began to recognise an unprecedented opportunity.

Trump was prepared not only to promote the cause of corporations in government, but to turn government into a kind of corporation, staffed and run by executives and lobbyists. His incoherence was not a liability, but an opening: his agenda could be shaped. And the dark money network already developed by some American corporations was perfectly positioned to shape it. Dark money is the term used in the US for the funding of organisations involved in political advocacy that are not obliged to disclose where the money comes from. Few people would see a tobacco company as a credible source on public health, or a coal company as a neutral commentator on climate change. In order to advance their political interests, such companies must pay others to speak on their behalf.

Soon after the second world war, some of America’s richest people began setting up a network of thinktanks to promote their interests. These purport to offer dispassionate opinions on public affairs. But they are more like corporate lobbyists, working on behalf of those who fund them.

We have no hope of understanding what is coming until we understand how the dark money network operates. The remarkable story of a British member of parliament provides a unique insight into this network, on both sides of the Atlantic. His name is Liam Fox. Six years ago, his political career seemed to be over when he resigned as defence secretary after being caught mixing his private and official interests. But today he is back on the front bench, and with a crucial portfolio: secretary of state for international trade.

In 1997, the year the Conservatives lost office to Tony Blair, Fox, who is on the hard right of the Conservative party, founded an organisation called The Atlantic Bridge. Its patron was Margaret Thatcher. On its advisory council sat future cabinet ministers Michael Gove, George Osborne, William Hague and Chris Grayling. Fox, a leading campaigner for Brexit, described the mission of Atlantic Bridge as “to bring people together who have common interests”. It would defend these interests from “European integrationists who would like to pull Britain away from its relationship with the United States”.

Atlantic Bridge was later registered as a charity. In fact it was part of the UK’s own dark money network: only after it collapsed did we discover the full story of who had funded it. Its main sponsor was the immensely rich Michael Hintze, who worked at Goldman Sachs before setting up the hedge fund CQS. Hintze is one of the Conservative party’s biggest donors. In 2012 he was revealed as a funder of the Global Warming Policy Foundation, which casts doubt on the science of climate change. As well as making cash grants and loans to Atlantic Bridge, he lent Fox his private jet to fly to and from Washington.

Another funder was the pharmaceutical company Pfizer. It paid for a researcher at Atlantic Bridge called Gabby Bertin. She went on to become David Cameron’s press secretary, and now sits in the House of Lords: Cameron gave her a life peerage in his resignation honours list.

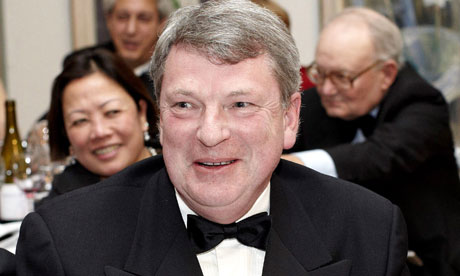

Trade secretary Liam Fox. Photograph: Daniel Leal-Olivas/AFP/Getty Images

In 2007, a group called the American Legislative Exchange Council (Alec) set up a sister organisation, the Atlantic Bridge Project. Alec is perhaps the most controversial corporate-funded thinktank in the US. It specialises in bringing together corporate lobbyists with state and federal legislators to develop “model bills”. The legislators and their families enjoy lavish hospitality from the group, then take the model bills home with them, to promote as if they were their own initiatives.

Alec has claimed that more than 1,000 of its bills are introduced by legislators every year, and one in five of them becomes law. It has been heavily funded by tobacco companies, the oil company Exxon, drug companies and Charles and David Koch – the billionaires who founded the first Tea Party organisations. Pfizer, which funded Bertin’s post at Atlantic Bridge, sits on Alec’s corporate board. Some of the most contentious legislation in recent years, such as state bills lowering the minimum wage, bills granting corporations immunity from prosecution and the “ag-gag” laws – forbidding people to investigate factory farming practices – were developed by Alec.

To run the US arm of Atlantic Bridge, Alec brought in its director of international relations, Catherine Bray. She is a British woman who had previously worked forthe Conservative MEP Richard Ashworth and the Ukip MEP Roger Helmer. Bray has subsequently worked for Conservative MEP and Brexit campaigner Daniel Hannan. Her husband is Wells Griffith, the battleground states director for Trump’s presidential campaign.

Among the members of Atlantic Bridge’s US advisory council were the ultra-conservative senators James Inhofe, Jon Kyl and Jim DeMint. Inhofe is reported to have received over $2m in campaign finance from coal and oil companies. Both Koch Industries and ExxonMobil have been major donors.

Kyl, now retired, is currently acting as the “sherpa” guiding Jeff Sessions’s nomination as Trump’s attorney general through the Senate. Jim DeMint resigned his seat in the Senate to become president of the Heritage Foundation – the thinktank founded with a grant from Joseph Coors of the Coors brewing empire, and built up with money from the banking and oil billionaire Richard Mellon Scaife. Like Alec, it has been richly funded by the Koch brothers. Heritage, under DeMint’s presidency, drove the attempt to ensure that Congress blocked the federal budget, temporarily shutting down the government in 2013. Fox’s former special adviser at the Ministry of Defence, an American called Luke Coffey, now works for the foundation.

Former Arizona senator Jon Kyl. Photograph: Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images

The Heritage Foundation is now at the heart of Trump’s administration. Its board members, fellows and staff comprise a large part of his transition team. Among them are Rebekah Mercer, who sits on Trump’s executive committee; Steven Groves and Jim Carafano (State Department); Curtis Dubay (Treasury); and Ed Meese, Paul Winfree, Russ Vought and John Gray (management and budget). CNN reports that “no other Washington institution has that kind of footprint in the transition”.

Trump’s extraordinary plan to cut federal spending by $10.5tn was drafted by the Heritage Foundation, which called it a “blueprint for a new administration”. Vought and Gray, who moved on to Trump’s team from Heritage, are now turning this blueprint into his first budget.

This will, if passed, inflict devastating cuts on healthcare, social security, legal aid, financial regulation and environmental protections; eliminate programmes to prevent violence against women, defend civil rights and fund the arts; and will privatise the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Trump, as you follow this story, begins to look less like a president and more like an intermediary, implementing an agenda that has been handed down to him.

In July last year, soon after he became trade secretary, Liam Fox flew to Washington. One of his first stops was a place he has visited often over the past 15 years: the office of the Heritage Foundation, where he spoke to, among others, Jim DeMint. A freedom of information request reveals that one of the topics raised at the meeting was the European ban on American chicken washed in chlorine: a ban that producers hope the UK will lift under a new trade agreement. Afterwards, Fox wrote to DeMint, looking forward to “working with you as the new UK government develops its trade policy priorities, including in high value areas that we discussed such as defence”.

How did Fox get to be in this position, after the scandal that brought him down in 2011? The scandal itself provides a clue: it involved a crossing of the boundaries between public and private interests. The man who ran the UK branch of Atlantic Bridge was his friend Adam Werritty, who operated out of Michael Hintze’s office building. Werritty’s work became entangled with Fox’s official business as defence secretary. Werritty, who carried a business card naming him as Fox’s adviser but was never employed by the Ministry of Defence, joined the secretary of state on numerous ministerial visits overseas, and made frequent visits to Fox’s office.

By the time details of this relationship began to leak, the charity commission had investigated Atlantic Bridge and determined that its work didn’t look very charitable. It had to pay back the tax from which it had been exempted (Hintze picked up the bill). In response, the trustees shut the organisation down. As the story about Werritty’s unauthorised involvement in government business began to grow, Fox made a number of misleading statements. He was left with no choice but to resign.

When Theresa May brought Fox back into government, it was as strong a signal as we might receive about the intentions of her government. The trade treaties that Fox is charged with developing set the limits of sovereignty. US food and environmental standards tend to be lower than Britain’s, and will become lower still if Trump gets his way. Any trade treaty we strike will create a common set of standards for products and services. Trump’s administration will demand that ours are adjusted downwards, so that US corporations can penetrate our markets without having to modify their practices. All the cards, post-Brexit vote, are in US hands: if the UK doesn’t cooperate, there will be no trade deal.

May needed someone who is unlikely to resist. She chose Fox, who has become an indispensable member of her team. The shadow diplomatic mission he developed through Atlantic Bridge plugs him straight into the Trump administration.

Long before Trump won, campaign funding in the US had systematically corrupted the political system. A new analysis by US political scientists finds an almost perfect linear relationship, across 32 years, between the money gathered by the two parties for congressional elections and their share of the vote. But there has also been a shift over these years: corporate donors have come to dominate this funding.

By tying our fortunes to those of the United States, the UK government binds us into this system. This is part of what Brexit was about: European laws protecting the public interest were portrayed by Conservative Eurosceptics as intolerable intrusions on corporate freedom. Taking back control from Europe means closer integration with the US. The transatlantic special relationship is a special relationship between political and corporate power. That power is cemented by the networks Liam Fox helped to develop.

In April 1938, President Franklin Roosevelt sent the US Congress the following warning: “The liberty of a democracy is not safe if the people tolerate the growth of private power to a point where it becomes stronger than their democratic state itself. That, in its essence, is fascism.” It is a warning we would do well to remember.