Ramachandra Guha in NDTV

When, towards the end of the first decade of the present century, Narendra Modi began speaking frequently about something he called the 'Gujarat Model', it was the second time a state of the Indian Union had that grand, self-promoting, suffix added to its name. The first was Kerala. The origins of the term 'Kerala Model' go back to a study done in the 1970s by economists associated with the Centre for Development Studies in Thiruvananthapuram. This showed that when it came to indices of population (as in declining birth rates), education (as in remarkably high literacy for women) and health (as in lower infant mortality and higher life expectancy), this small state in a desperately poor country had done as well - and sometimes better - than parts of Europe and North America.

Boosted to begin with by economists and demographers, Kerala soon came in for praise from sociologists and political scientists. The former argued that caste and class distinctions had radically diminished in Kerala over the course of the 20th century; the latter showed that, when it came to implementing the provisions of the 73rd and 74th Amendments to the Constitution, Kerala was ahead of other states. More power had been devolved to municipalities and panchayats than elsewhere in India.

Success, as John F. Kennedy famously remarked, has many fathers (while failure is an orphan). When these achievements of the state of Kerala became widely known, many groups rushed to claim their share of the credit. The communists, who had been in power for long stretches, said it was their economic radicalism that did it. Followers of Sri Narayana Guru (1855-1928) said it was the egalitarianism promoted by that great social reformer which led to much of what followed. Those still loyal to the royal houses of Travancore and Cochin observed that when it came to education, and especially girls' education, their Rulers were more progressive than Maharajas and Nawabs elsewhere. The Christian community of Kerala also chipped in, noting that some of the best schools, colleges, and hospitals were run by the Church. It was left to that fine Australian historian of Kerala and India, Robin Jeffrey, to critically analyse all these claims, and demonstrate in what order and what magnitude they contributed. His book Politics, Women and Wellbeing remains the definitive work on the subject.

Such were the elements of the 'Kerala Model'. What did the 'Gujarat Model' that Narendra Modi began speaking of, c. 2007, comprise? Mr Modi did not himself ever define it very precisely. But there is little doubt that the coinage itself was inspired and provoked by what had preceded it. The Gujarat Model would, Mr Modi was suggesting, be different from, and better than, the Kerala Model. Among the noticeable weaknesses of the latter was that it did not really encourage private enterprise. Marxist ideology and trade union politics both inhibited this. On the other hand, the Vibrant Gujarat Summits organized once every two years when Mr Modi was Chief Minister were intended precisely to attract private investment.

This openness to private capital was, for Mr Modi's supporters, undoubtedly the most attractive feature of what he was marketing as the 'Gujarat Model'. It was this that brought to him the support of big business, and of small business as well, when he launched his campaign for Prime Minister. Young professionals, disgusted by the cronyism and corruption of the UPA regime, flocked to his support, seeing him as a modernizing Messiah who would make India an economic powerhouse.

With the support of these groups, and many others, Narendra Modi was elected Prime Minister in May 2014.

There were other aspects of the Gujarat Model that Narendra Modi did not speak about, but which those who knew the state rather better than the Titans of Indian industry were perfectly aware of. These included the relegation of minorities (and particularly Muslims) to second-class status; the centralization of power in the Chief Minister and the creation of a cult of personality around him; attacks on the independence and autonomy of universities; curbs on the freedom of the press; and, not least, a vengeful attitude towards critics and political rivals.

These darker sides of the Gujarat Model were all played down in Mr Modi's Prime Ministerial campaign. But in the six years since he has been in power at the Centre, they have become starkly visible. The communalization of politics and of popular discourse, the capturing of public institutions, the intimidation of the press, the use of the police and investigating agencies to harass opponents, and, perhaps above all, the deification of the Great Leader by the party, the Cabinet, the Government, and the Godi Media - these have characterized the Prime Ministerial tenure of Narendra Modi. Meanwhile, the most widely advertised positive feature of the Gujarat Model before 2014 has proved to be a dud. Far from being a free-market reformer, Narendra Modi has demonstrated that he is an absolute statist in economic matters. As an investment banker who once enthusiastically supported him recently told me in disgust: "Narendra Modi is our most left-wing Prime Minister ever - he is even more left-wing than Jawaharlal Nehru".

Which brings me back to the Kerala Model, which the Gujarat Model sought to replace or supplant. Talked about a great deal in the 1980s and 1990s, in recent years, the term was not much heard in policy discourse any more. It had fallen into disuse, presumably consigned to the dustbin of history. The onset of COVID-19 has now thankfully rescued it, and indeed brought it back to centre-stage. For in how it has confronted, tackled, and tamed the COVID crisis, Kerala has once again showed itself to be a model for India - and perhaps the world.

There has been some excellent reporting on how Kerala flattened the curve. It seems clear that there is a deeper historical legacy behind the success of this state. Because the people of Kerala are better educated, they have followed the practices in their daily life least likely to allow community transmission. Because they have such excellent health care, if people do test positive, they can be treated promptly and adequately. Because caste and gender distinctions are less extreme than elsewhere in India, access to health care and medical information is less skewed. Because decentralization of power is embedded in systems of governance, panchayat heads do not have to wait for a signal from a Big Boss before deciding to act. There are two other features of Kerala's political culture that have helped them in the present context; its top leaders are generally more grounded and less imperious than elsewhere, and bipartisanship comes more easily to the state's politicians.

The state of Kerala is by no means perfect. While there have been no serious communal riots for many decades, in everyday life there is still some amount of reserve in relations between Hindus, Christians and Muslims. Casteism and patriarchy have been weakened, but by no means eliminated. The intelligentsia still remain unreasonably suspicious of private enterprise, which will hurt the state greatly in the post-COVID era, after remittances from the Gulf have dried up.

For all their flaws, the state and people of Kerala have many things to teach us, who live in the rest of India. We forgot about their virtues in the past decade, but now these virtues are once more being discussed, to both inspire and chastise us. The success of the state in the past and in the present have rested on science, transparency, decentralization, and social equality. These are, as it were, the four pillars of the Kerala Model. On the other hand, the four pillars of the Gujarat Model are superstition, secrecy, centralization, and communal bigotry. Give us the first over the second, any day.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label trade union. Show all posts

Showing posts with label trade union. Show all posts

Saturday, 25 April 2020

Sunday, 26 March 2017

Populism is the result of global economic failure

Larry Elliott in The Guardian

The rise of populism has rattled the global political establishment. Brexit came as a shock, as did the victory of Donald Trump. Much head-scratching has resulted as leaders seek to work out why large chunks of their electorates are so cross.

The answer seems pretty simple. Populism is the result of economic failure. The 10 years since the financial crisis have shown that the system of economic governance that has held sway for the past four decades is broken. Some call this approach neoliberalism. Perhaps a better description would be unpopulism.

Unpopulism meant tilting the balance of power in the workplace in favour of management and treating people like wage slaves. Unpopulism was rigged to ensure that the fruits of growth went to the few not to the many. Unpopulism decreed that those responsible for the global financial crisis got away with it while those who were innocent bore the brunt of austerity.

Anybody seeking to understand why Trump won the US presidential election should take a look at what has been happening to the division of the economic spoils. The share of national income that went to the bottom 90% of the population held steady at around 66% from 1950 to 1980. It then began a steep decline, falling to just over 50% when the financial crisis broke in 2007.

Similarly, it is no longer the case that everybody benefits when the US economy is doing well. During the business cycle upswing between 1961 and 1969, the bottom 90% of Americans took 67% of the income gains. During the Reagan expansion two decades later they took 20%. During the Greenspan housing bubble of 2001 to 2007, they got just two cents in every extra dollar of national income generated while the richest 10% took the rest.

Those responsible for global financial crisis got away with it while those who were innocent bore the brunt of austerity

The US economist Thomas Palley* says that up until the late 1970s countries operated a virtuous circle growth model in which wages were the engine of demand growth.

“Productivity growth drove wage growth which fueled demand growth. That promoted full employment which provided the incentive to invest, which drove further productivity growth,” he says.

Unpopulism was touted as the antidote to the supposedly-failed policies of the post-war era. It promised higher growth rates, higher investment rates, higher productivity rates and a trickle down of income from rich to poor. It has delivered none of these things.

James Montier and Philip Pilkington of the global investment firm GMO say that the system that arose in the 1970s was characterised by four significant economic policies: the abandonment of full employment and its replacement with inflation targeting; an increase in the globalisation of the flows of people, capital and trade; a focus on shareholder maximisation rather than reinvestment and growth; and the pursuit of flexible labour markets and the disruption of trade unions and workers’ organisations.

To take just the last of these four pillars, the idea was that trade unions and minimum wages were impediments to an efficient labour market. Collective bargaining and statutory pay floors would result in workers being paid more than the market rate, with the result that unemployment would inevitably rise.

Unpopulism decreed that the real value of the US minimum wage should be eroded. But unemployment is higher than it was when the minimum wage was worth more. Nor is there any correlation between trade union membership and unemployment. If anything, international comparisons suggest that those countries with higher trade union density have lower jobless rates. The countries that have higher minimum wages do not have higher unemployment rates.

“Labour market flexibility may sound appealing, but it is based on a theory that runs completely counter to all the evidence we have,” Montier and Pilkington note. “The alternative theory suggests that labour market flexibility is by no means desirable as it results in an economy with a bias to stagnate that can only maintain high rates of employment and economic growth through debt-fuelled bubbles that inevitably blow up, leading to the economy tipping back into stagnation.”

This quest for ever-greater labour-market flexibility has had some unexpected consequences. The bill in the UK for tax credits spiralled quickly once firms realised that they could pay poverty wages and let the state pick up the bill. Access to a global pool of low-cost labour meant there was less of an incentive to invest in productivity-enhancing equipment.

The abysmally-low levels of productivity growth since the crisis have encouraged the belief that this is a recent phenomenon, but as Andy Haldane, the Bank of England’s chief economist, noted last week, the trend started in most advanced countries in the 1970s.

“Certainly, the productivity puzzle is not something which has emerged since the global financial crisis, though it seems to have amplified pre-existing trends,” Haldane said.

Bolshie trade unions certainly can’t be blamed for Britain’s lost productivity decade. The orthodox view in the 1970s was that attempts to make the UK more efficient were being thwarted by shop stewards who modeled themselves on Fred Kite, the character played by Peter Sellers in I’m Alright Jack. Haldane puts the blame elsewhere: on poor management, which has left the UK with a big gap between frontier firms and a long tail of laggards. “Firms which export have systematically higher levels of productivity than domestically-oriented firms, on average by around a third. The same is true, even more dramatically, for foreign-owned firms. Their average productivity is twice that of domestically-oriented firms.”

Wolfgang Streeck: the German economist calling time on capitalism

Read more

Populism is seen as irrational and reprehensible. It is neither. It seems entirely rational for the bottom 90% of the US population to question why they are getting only 2% of income gains. It hardly seems strange that workers in Britain should complain at the weakest decade for real wage growth since the Napoleonic wars.

It has also become clear that ultra-low interest rates and quantitative easing are merely sticking-plaster solutions. Populism stems from a sense that the economic system is not working, which it clearly isn’t. In any other walk of life, a failed experiment results in change. Drugs that are supposed to provide miracle cures but are proved not to work are quickly abandoned. Businesses that insist on continuing to produce goods that consumers don’t like go bust. That’s how progress happens.

The good news is that the casting around for new ideas has begun. Trump has advocated protectionism. Theresa May is consulting on an industrial strategy. Montier and Pilkington suggest a commitment to full employment, job guarantees, re-industrialisation and a stronger role for trade unions. The bad news is that time is running short. More and more people are noticing that the emperor has no clothes.

Even if the polls are right this time and Marine Le Pen fails to win the French presidency, a full-scale political revolt is only another deep recession away. And that’s easy enough to envisage.

The rise of populism has rattled the global political establishment. Brexit came as a shock, as did the victory of Donald Trump. Much head-scratching has resulted as leaders seek to work out why large chunks of their electorates are so cross.

The answer seems pretty simple. Populism is the result of economic failure. The 10 years since the financial crisis have shown that the system of economic governance that has held sway for the past four decades is broken. Some call this approach neoliberalism. Perhaps a better description would be unpopulism.

Unpopulism meant tilting the balance of power in the workplace in favour of management and treating people like wage slaves. Unpopulism was rigged to ensure that the fruits of growth went to the few not to the many. Unpopulism decreed that those responsible for the global financial crisis got away with it while those who were innocent bore the brunt of austerity.

Anybody seeking to understand why Trump won the US presidential election should take a look at what has been happening to the division of the economic spoils. The share of national income that went to the bottom 90% of the population held steady at around 66% from 1950 to 1980. It then began a steep decline, falling to just over 50% when the financial crisis broke in 2007.

Similarly, it is no longer the case that everybody benefits when the US economy is doing well. During the business cycle upswing between 1961 and 1969, the bottom 90% of Americans took 67% of the income gains. During the Reagan expansion two decades later they took 20%. During the Greenspan housing bubble of 2001 to 2007, they got just two cents in every extra dollar of national income generated while the richest 10% took the rest.

Those responsible for global financial crisis got away with it while those who were innocent bore the brunt of austerity

The US economist Thomas Palley* says that up until the late 1970s countries operated a virtuous circle growth model in which wages were the engine of demand growth.

“Productivity growth drove wage growth which fueled demand growth. That promoted full employment which provided the incentive to invest, which drove further productivity growth,” he says.

Unpopulism was touted as the antidote to the supposedly-failed policies of the post-war era. It promised higher growth rates, higher investment rates, higher productivity rates and a trickle down of income from rich to poor. It has delivered none of these things.

James Montier and Philip Pilkington of the global investment firm GMO say that the system that arose in the 1970s was characterised by four significant economic policies: the abandonment of full employment and its replacement with inflation targeting; an increase in the globalisation of the flows of people, capital and trade; a focus on shareholder maximisation rather than reinvestment and growth; and the pursuit of flexible labour markets and the disruption of trade unions and workers’ organisations.

To take just the last of these four pillars, the idea was that trade unions and minimum wages were impediments to an efficient labour market. Collective bargaining and statutory pay floors would result in workers being paid more than the market rate, with the result that unemployment would inevitably rise.

Unpopulism decreed that the real value of the US minimum wage should be eroded. But unemployment is higher than it was when the minimum wage was worth more. Nor is there any correlation between trade union membership and unemployment. If anything, international comparisons suggest that those countries with higher trade union density have lower jobless rates. The countries that have higher minimum wages do not have higher unemployment rates.

“Labour market flexibility may sound appealing, but it is based on a theory that runs completely counter to all the evidence we have,” Montier and Pilkington note. “The alternative theory suggests that labour market flexibility is by no means desirable as it results in an economy with a bias to stagnate that can only maintain high rates of employment and economic growth through debt-fuelled bubbles that inevitably blow up, leading to the economy tipping back into stagnation.”

This quest for ever-greater labour-market flexibility has had some unexpected consequences. The bill in the UK for tax credits spiralled quickly once firms realised that they could pay poverty wages and let the state pick up the bill. Access to a global pool of low-cost labour meant there was less of an incentive to invest in productivity-enhancing equipment.

The abysmally-low levels of productivity growth since the crisis have encouraged the belief that this is a recent phenomenon, but as Andy Haldane, the Bank of England’s chief economist, noted last week, the trend started in most advanced countries in the 1970s.

“Certainly, the productivity puzzle is not something which has emerged since the global financial crisis, though it seems to have amplified pre-existing trends,” Haldane said.

Bolshie trade unions certainly can’t be blamed for Britain’s lost productivity decade. The orthodox view in the 1970s was that attempts to make the UK more efficient were being thwarted by shop stewards who modeled themselves on Fred Kite, the character played by Peter Sellers in I’m Alright Jack. Haldane puts the blame elsewhere: on poor management, which has left the UK with a big gap between frontier firms and a long tail of laggards. “Firms which export have systematically higher levels of productivity than domestically-oriented firms, on average by around a third. The same is true, even more dramatically, for foreign-owned firms. Their average productivity is twice that of domestically-oriented firms.”

Wolfgang Streeck: the German economist calling time on capitalism

Read more

Populism is seen as irrational and reprehensible. It is neither. It seems entirely rational for the bottom 90% of the US population to question why they are getting only 2% of income gains. It hardly seems strange that workers in Britain should complain at the weakest decade for real wage growth since the Napoleonic wars.

It has also become clear that ultra-low interest rates and quantitative easing are merely sticking-plaster solutions. Populism stems from a sense that the economic system is not working, which it clearly isn’t. In any other walk of life, a failed experiment results in change. Drugs that are supposed to provide miracle cures but are proved not to work are quickly abandoned. Businesses that insist on continuing to produce goods that consumers don’t like go bust. That’s how progress happens.

The good news is that the casting around for new ideas has begun. Trump has advocated protectionism. Theresa May is consulting on an industrial strategy. Montier and Pilkington suggest a commitment to full employment, job guarantees, re-industrialisation and a stronger role for trade unions. The bad news is that time is running short. More and more people are noticing that the emperor has no clothes.

Even if the polls are right this time and Marine Le Pen fails to win the French presidency, a full-scale political revolt is only another deep recession away. And that’s easy enough to envisage.

Wednesday, 10 August 2016

Corbyn supporters are not delusional Leninists but ordinary, fed-up voters

Ellie Mae O'Hagan in The Guardian

'We're not cult members': Labour supporters at Corbyn rallies

I am, of course, talking about the people who support Jeremy Corbyn – 12,000 of whom have joined Momentum, the activist movement that propelled Corbyn to power. And after Monday’s high court win and a clean sweep in the elections to Labour’s national executive committee, support for Corbyn shows no signs of abating – despite continued suggestions that those supporters are nothing more than an abusive rabble. How many of the journalists writing panicked screeds about these awful people have actually met any of them, do you think? I ask because writing about the Corbyn phenomenon over the last year means I’ve met probably hundreds of his supporters and to be honest, I find dealing with them the most pleasant element of writing about Corbyn.

A couple of months ago, I went to a political event that included a branch of Momentum. All young women; they were energetic, funny and very friendly. Two weeks ago, I had a debate with a Momentum member about Corbyn’s media strategy. Of the two of us, it was me who was the ruder, more impatient one. When Corbyn ran for leadership last year, I visited phone banks for him dozens of times, and spent hours in the company of the very people who went on to found Momentum. I told myself I was researching a piece; actually I think I just liked talking to them.

Sure, my experiences of these Corbyn supporters might not be representative. But they do suggest that the depiction of them as a madcap bunch of deluded cultists is not representative either. Broadly speaking, the media has failed to understand the political moment in the Labour party; it has shown a damning lack of interest in the fact that people who had previously written off party politics are now flocking towards it in their hundreds of thousands – preferring instead to dismiss them as an angry mob.

One half of that description is accurate, however. Corbyn supporters may not be a mob, but they are angry. And to understand why, it is useful to consider the words of the academic Jeremy Gilbert, a longstanding Labour member and activist who has joined Momentum: “Momentum is simply trying to give a voice to a body of opinion which has been widespread throughout the country for many years, but has been denied any kind of place in our public life since the early days of New Labour. It is a body of opinion which believes, with good reason, that the embrace of neoliberal economics and neoconservative foreign policy under Blair was a disaster … Naturally some of those voices, suppressed for so long, sound raucous, aggressive and uncouth.”

The anger that commentators detect in the Corbyn movement, in my experience, is not a symptom of the fact that it has been infiltrated by bullies – but that its members feel as though the Labour coup is as much an attack on their right to participate in public discourse as it is on Corbyn.

Everything the left traditionally stands for – from human rights and socialism to a foreign policy driven by diplomacy – has been, at best, marginalised and, at worst, actively mocked in mainstream political discourse since the 1970s. And nowhere is this more apparent than in the depiction of the trade unions, the last bastions of organised British socialism, as insidious barons intent on wrecking British life (a claim that sounds particularly ludicrous when made by newspapers who supported the Conservatives at the last election – a party consisting of members of the actual landed gentry).

I am yet to meet a single Corbynite who is naive about Corbyn’s failings as a leader, the great challenges he faces, or who does not want to win a general election. But the reason so many have coalesced around him anyway is because they view his leadership as the only opportunity they have had in at least 30 years to see their views finally represented in public life. The Labour rebels’ attempt to unseat him is, in their minds, as much an attempt to excommunicate the wider left as it is to get rid of Corbyn himself. Perhaps the most salient evidence of this is the decision to charge affiliate members £25 to vote in the leadership election, and ban outright members who joined fewer than six months ago – a decision that has now been overturned in court.

Worse still for Corbyn supporters, the policy positions they have taken over the last 30 years have often been proven right. Lack of social housing has led to a spiralling housing crisis; the deregulation of the financial industry would have caused economic collapse had it not been for state intervention; queasiness around public ownership has caused escalating transport costs and arguably the shambles that is Southern Railway; inequality is the UK’s most pressing social issue; a reluctance to rein in fossil fuel companies has led to a climate emergency; and even Tony Blair accepts that the Iraq war may have led to the rise of Isis. This is why so many Corbyn supporters are upset by the coup, and why they have decided to back him unequivocally, in spite of the incompetence that has at times been part of his leadership.

I have a lot of sympathy with Owen Smith supporters who are horrified by Labour’s poll ratings. But I have zero sympathy with those in the party who have been utterly unwilling to engage with Corbyn supporters, and who have not reflected on why they lost control of their party to someone they so clearly regard as useless. There are simply not enough delusional Leninists in Britain to make up the entirety of Corbyn’s support – these are ordinary British voters who want radical solutions to a growing number of crises. And until they are listened to and taken seriously, Corbyn and the movement keeping him in power is not going anywhere.

‘Members of Momentum feel as though the Labour coup is as much an attack on their right to participate in public discourse as it is on Jeremy Corbyn.’ Photograph: Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images

Lock up your children, for there is a sinister force taking root in modern Britain. It is a cult, with followers like those of mass murderer Charles Manson, shrouded in a cloud of spite and acrimony. The worst thing about this terrifying insurgency? My mum is part of it.

Lock up your children, for there is a sinister force taking root in modern Britain. It is a cult, with followers like those of mass murderer Charles Manson, shrouded in a cloud of spite and acrimony. The worst thing about this terrifying insurgency? My mum is part of it.

'We're not cult members': Labour supporters at Corbyn rallies

I am, of course, talking about the people who support Jeremy Corbyn – 12,000 of whom have joined Momentum, the activist movement that propelled Corbyn to power. And after Monday’s high court win and a clean sweep in the elections to Labour’s national executive committee, support for Corbyn shows no signs of abating – despite continued suggestions that those supporters are nothing more than an abusive rabble. How many of the journalists writing panicked screeds about these awful people have actually met any of them, do you think? I ask because writing about the Corbyn phenomenon over the last year means I’ve met probably hundreds of his supporters and to be honest, I find dealing with them the most pleasant element of writing about Corbyn.

A couple of months ago, I went to a political event that included a branch of Momentum. All young women; they were energetic, funny and very friendly. Two weeks ago, I had a debate with a Momentum member about Corbyn’s media strategy. Of the two of us, it was me who was the ruder, more impatient one. When Corbyn ran for leadership last year, I visited phone banks for him dozens of times, and spent hours in the company of the very people who went on to found Momentum. I told myself I was researching a piece; actually I think I just liked talking to them.

Sure, my experiences of these Corbyn supporters might not be representative. But they do suggest that the depiction of them as a madcap bunch of deluded cultists is not representative either. Broadly speaking, the media has failed to understand the political moment in the Labour party; it has shown a damning lack of interest in the fact that people who had previously written off party politics are now flocking towards it in their hundreds of thousands – preferring instead to dismiss them as an angry mob.

One half of that description is accurate, however. Corbyn supporters may not be a mob, but they are angry. And to understand why, it is useful to consider the words of the academic Jeremy Gilbert, a longstanding Labour member and activist who has joined Momentum: “Momentum is simply trying to give a voice to a body of opinion which has been widespread throughout the country for many years, but has been denied any kind of place in our public life since the early days of New Labour. It is a body of opinion which believes, with good reason, that the embrace of neoliberal economics and neoconservative foreign policy under Blair was a disaster … Naturally some of those voices, suppressed for so long, sound raucous, aggressive and uncouth.”

The anger that commentators detect in the Corbyn movement, in my experience, is not a symptom of the fact that it has been infiltrated by bullies – but that its members feel as though the Labour coup is as much an attack on their right to participate in public discourse as it is on Corbyn.

Everything the left traditionally stands for – from human rights and socialism to a foreign policy driven by diplomacy – has been, at best, marginalised and, at worst, actively mocked in mainstream political discourse since the 1970s. And nowhere is this more apparent than in the depiction of the trade unions, the last bastions of organised British socialism, as insidious barons intent on wrecking British life (a claim that sounds particularly ludicrous when made by newspapers who supported the Conservatives at the last election – a party consisting of members of the actual landed gentry).

I am yet to meet a single Corbynite who is naive about Corbyn’s failings as a leader, the great challenges he faces, or who does not want to win a general election. But the reason so many have coalesced around him anyway is because they view his leadership as the only opportunity they have had in at least 30 years to see their views finally represented in public life. The Labour rebels’ attempt to unseat him is, in their minds, as much an attempt to excommunicate the wider left as it is to get rid of Corbyn himself. Perhaps the most salient evidence of this is the decision to charge affiliate members £25 to vote in the leadership election, and ban outright members who joined fewer than six months ago – a decision that has now been overturned in court.

Worse still for Corbyn supporters, the policy positions they have taken over the last 30 years have often been proven right. Lack of social housing has led to a spiralling housing crisis; the deregulation of the financial industry would have caused economic collapse had it not been for state intervention; queasiness around public ownership has caused escalating transport costs and arguably the shambles that is Southern Railway; inequality is the UK’s most pressing social issue; a reluctance to rein in fossil fuel companies has led to a climate emergency; and even Tony Blair accepts that the Iraq war may have led to the rise of Isis. This is why so many Corbyn supporters are upset by the coup, and why they have decided to back him unequivocally, in spite of the incompetence that has at times been part of his leadership.

I have a lot of sympathy with Owen Smith supporters who are horrified by Labour’s poll ratings. But I have zero sympathy with those in the party who have been utterly unwilling to engage with Corbyn supporters, and who have not reflected on why they lost control of their party to someone they so clearly regard as useless. There are simply not enough delusional Leninists in Britain to make up the entirety of Corbyn’s support – these are ordinary British voters who want radical solutions to a growing number of crises. And until they are listened to and taken seriously, Corbyn and the movement keeping him in power is not going anywhere.

Thursday, 1 October 2015

The Tories are setting up their own trade union movement

Jon Stone in The Independent

The Conservative party is launching a new organisation to represent trade unionists who have Tory sympathies, it has said.

Robert Halfon, the Conservatives’ deputy chairman, said his party was now “the party of working people” and that “militant” union leaders were putting workers’ off existing structures.

“We want to provide a voice for Conservative-minded trade unionists and moderate trade unionists and this week we will announcing a new organisation in the Conservative party called the Conservative Workers and Trade Unionists movement and that is going to be a voice for Conservative trade unionists,” he said in an interview with parliament’s The House magazine.

“We are recreating the Conservative trade union workers’ movement. There will be a new website and people will be able to join. There will be a voice for moderate trade unionists who feel they may have sympathy with the Conservatives or even just feel that they’re not being represented by militant trade union leaders.”

The organisation could act as a caucus within existing workplace trade unions and allow the Tories to stand candidates in internal elections. It will be formally announced at the party’s conference in Manchester next week.

Robert Halfon: Deputy Conservative Chairman

The announcement comes as the Conservative government launches the biggest crackdown on trade unionists for 30 years.

Business Secretary Sajid Javid is moving to criminalise unlawful picketing, as well as new rules making it harder for workers to strike legally.

New financing rules will also make it far more difficult for trade unions to direct funds to Labour, the political party they founded.

Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn described the claim the Tories were a party for workers as an “absurd lie” in his speech to Labour’s annual conference in Brighton.

He pointed to cuts to tax credits that would leave people in work worse off, even after a steep rise in the minimum wage.

“We’ll fight this every inch of the way and we’ll campaign at the workplace, in every community against this Tory broken promise and to expose the absurd lie that the Tories are on the side of working people, that they are giving Britain a pay rise,” Mr Corbyn said.

Research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies found that the rebranded higher minimum wage introduced by George Osborne in the Budget came “nowhere near” to compensating for benefit cuts.

Other research conducted by the institute found that the sharpest benefit cuts would fall on people with jobs.

The Conservative party is launching a new organisation to represent trade unionists who have Tory sympathies, it has said.

Robert Halfon, the Conservatives’ deputy chairman, said his party was now “the party of working people” and that “militant” union leaders were putting workers’ off existing structures.

“We want to provide a voice for Conservative-minded trade unionists and moderate trade unionists and this week we will announcing a new organisation in the Conservative party called the Conservative Workers and Trade Unionists movement and that is going to be a voice for Conservative trade unionists,” he said in an interview with parliament’s The House magazine.

“We are recreating the Conservative trade union workers’ movement. There will be a new website and people will be able to join. There will be a voice for moderate trade unionists who feel they may have sympathy with the Conservatives or even just feel that they’re not being represented by militant trade union leaders.”

The organisation could act as a caucus within existing workplace trade unions and allow the Tories to stand candidates in internal elections. It will be formally announced at the party’s conference in Manchester next week.

Robert Halfon: Deputy Conservative Chairman

The announcement comes as the Conservative government launches the biggest crackdown on trade unionists for 30 years.

Business Secretary Sajid Javid is moving to criminalise unlawful picketing, as well as new rules making it harder for workers to strike legally.

New financing rules will also make it far more difficult for trade unions to direct funds to Labour, the political party they founded.

Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn described the claim the Tories were a party for workers as an “absurd lie” in his speech to Labour’s annual conference in Brighton.

He pointed to cuts to tax credits that would leave people in work worse off, even after a steep rise in the minimum wage.

“We’ll fight this every inch of the way and we’ll campaign at the workplace, in every community against this Tory broken promise and to expose the absurd lie that the Tories are on the side of working people, that they are giving Britain a pay rise,” Mr Corbyn said.

Research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies found that the rebranded higher minimum wage introduced by George Osborne in the Budget came “nowhere near” to compensating for benefit cuts.

Other research conducted by the institute found that the sharpest benefit cuts would fall on people with jobs.

Sunday, 23 August 2015

Once, firms cherished their workers. Now they are seen as disposable

Will Hutton in The Guardian

July 1909: a street in Bournville village near Birmingham, a new town founded by chocolate manufacturer and social reformer George Cadbury. Photograph: Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

More than 100 years ago, the Cadbury family built a model town, Bournville, for their workers, away from the overcrowded tenements of central Birmingham. Cadbury’s vast chocolate factory was at the centre of thousands of purpose-built villas, a village green, schools, churches and civic halls.

The message was clear. Cadbury cherished and invested in their workers, expecting commitment and loyalty back, which they got. Sir Adrian Cadbury, now in his 80s, still proudly shows visitors how his Quaker forefathers felt a genuine sense of responsibility to their workers. His family believed in capitalism for a purpose – innovation and human betterment.

Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, would regard the Cadbury family as crazed. His relationship with his workforce is entirely transactional: they are to give their heart and soul to Amazon, undertaking to follow Amazon’s “leadership principles”, set on a laminated card given to every employee, and can expect to be summarily sacked if they don’t make the grade. These injunctions are aimed at not only Amazon’s fork-lift truck drivers and packagers but also at its executive workforce.

At first glance, the principles seem unexceptional, exhorting “ Amazonians” to be obsessed with customers, drive for the best and think big. In practice, they mean workers have to be available to Amazon virtually every waking hour, as a devastating article claimed in last week’s New York Times. The workers should attack each other’s ideas in the name of “creative challenge” and buy into the paranoid culture Bezos believes is essential to business success, with their hourly performance fed into computers for Big Brother Bezos to monitor.

Working at Amazon has become synonymous with stress, conflict and tears – or, if you swim rather than sink, a chance to flourish. It is, as one former executive described it, “purposeful Darwinism”: if the majority of the workforce can flourish in such a culture, you have a successful company. Bezos would claim in his defence that he has founded the US’s most valuable retailer that ships two billion items a year. Cadbury ended up being taken over. Better his approach to capitalism than defunct Quakers, except now everyone is expendable. This is the route to success. Or is it?

The nature of firms is changing. The capitalist world of the so-called golden age between 1945 and the first oil crisis in 1974 was defined by Cadbury-type companies. Even if they didn’t build estates in which their workers could live, big companies offered paid holidays, guaranteed pensions related to your final salary, sickness benefit and recognised trade unions. Above all, they offered the chance of a career and personal progression.

This was the domain of the corporation man commuting to a steady job in a steady office in a steady company with their blue-collar counterparts no less secure in a steady factor. It delivered though. If western economies could again grow consistently at 3% or 4%, underpinned by matching growth in productivity, there would be delight all round.

The companies were much more exciting than they looked. They were purposeful – repositories of skills and knowledge, seeking out new markets, applying new technologies with an appetite for growth. In Britain, great companies such as ICI, Glaxo, EMI, Unilever, Thorn, British Aircraft Corporation, Marconi along with Cadbury were centres of growth and innovation.

A critical doctrine at the time was they were held back by trade unions and soft economic policy that encouraged inflation. The proof that inflation was so damaging is scant and beyond the print, coal, rail and motor industries, British trade unions were pretty weak and pliant. What instead held these companies back was the evaporation of the guaranteed markets of empire. Second, a short-term, gentlemanly, disengaged financial system was unable to mobilise resource behind these companies and their greater purpose as imperial markets shrank. That wasn’t widely understood then – and certainly not now. Instead, the economic problem was defined as pampered, unionised workers, a view further entrenched by an avalanche of free-market economics from the US. Worker privileges and rights must cease.

So to the firm of today. The new model firm no longer has workers who are members of the organisation in a relationship of mutual respect and shared mission with committed, long-term owners; rather, the new ownerless corporation with its tourist shareholders employs contractors who have to pay for benefits themselves and can be hired and fired at will.

They are throwaway people, middle-class workers at risk as much as their working-class peers. Unions are not welcome; pension benefits are scaled back; sickness, paternity and maternity benefits are pitched at the regulatory minimum. Last week, the Citizens Advice Bureau said it estimated that 460,000 people nationwide had been defined by employers as self-employed (and thus entitled to no company benefits), even though they worked regularly for one employer, often in office roles. It is the same approach that has delivered 1.4 million zero-hours contracts. All this allegedly is to serve growth. Except over the last 20 years, growth, productivity and innovation in both Britain and America have collapsed. These new firms whose only purpose is short-term profit with contractualised workforces turn out to be poor creators of long-term value. The exceptions, paradoxically, are the great hi-tech companies such as Amazon, Google, Apple and Facebook.

The alchemy of their success is they combine innovative technology, produce at continental scale, invest heavily and commit to a great purpose, usually because of the powerful personal commitment of the founder. Bezos may have constructed a Darwinian work environment but it is all “to be the Earth’s most customer-centric company”. He has invested hugely to achieve that end, but his workplaces, by contrast, seem terrible.

But even Bezos does not want to be depicted as an employer with no moral centre: he urged his employees to read the offending article and refer examples of bad practice to his human resources department.

Ultimately, long-term value creation can’t be done by treating your workforces as cattle. It’s the great debate about today’s capitalism. It would be a triumph if it was taken more seriously in Britain.

More than 100 years ago, the Cadbury family built a model town, Bournville, for their workers, away from the overcrowded tenements of central Birmingham. Cadbury’s vast chocolate factory was at the centre of thousands of purpose-built villas, a village green, schools, churches and civic halls.

The message was clear. Cadbury cherished and invested in their workers, expecting commitment and loyalty back, which they got. Sir Adrian Cadbury, now in his 80s, still proudly shows visitors how his Quaker forefathers felt a genuine sense of responsibility to their workers. His family believed in capitalism for a purpose – innovation and human betterment.

Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, would regard the Cadbury family as crazed. His relationship with his workforce is entirely transactional: they are to give their heart and soul to Amazon, undertaking to follow Amazon’s “leadership principles”, set on a laminated card given to every employee, and can expect to be summarily sacked if they don’t make the grade. These injunctions are aimed at not only Amazon’s fork-lift truck drivers and packagers but also at its executive workforce.

At first glance, the principles seem unexceptional, exhorting “ Amazonians” to be obsessed with customers, drive for the best and think big. In practice, they mean workers have to be available to Amazon virtually every waking hour, as a devastating article claimed in last week’s New York Times. The workers should attack each other’s ideas in the name of “creative challenge” and buy into the paranoid culture Bezos believes is essential to business success, with their hourly performance fed into computers for Big Brother Bezos to monitor.

Working at Amazon has become synonymous with stress, conflict and tears – or, if you swim rather than sink, a chance to flourish. It is, as one former executive described it, “purposeful Darwinism”: if the majority of the workforce can flourish in such a culture, you have a successful company. Bezos would claim in his defence that he has founded the US’s most valuable retailer that ships two billion items a year. Cadbury ended up being taken over. Better his approach to capitalism than defunct Quakers, except now everyone is expendable. This is the route to success. Or is it?

The nature of firms is changing. The capitalist world of the so-called golden age between 1945 and the first oil crisis in 1974 was defined by Cadbury-type companies. Even if they didn’t build estates in which their workers could live, big companies offered paid holidays, guaranteed pensions related to your final salary, sickness benefit and recognised trade unions. Above all, they offered the chance of a career and personal progression.

This was the domain of the corporation man commuting to a steady job in a steady office in a steady company with their blue-collar counterparts no less secure in a steady factor. It delivered though. If western economies could again grow consistently at 3% or 4%, underpinned by matching growth in productivity, there would be delight all round.

The companies were much more exciting than they looked. They were purposeful – repositories of skills and knowledge, seeking out new markets, applying new technologies with an appetite for growth. In Britain, great companies such as ICI, Glaxo, EMI, Unilever, Thorn, British Aircraft Corporation, Marconi along with Cadbury were centres of growth and innovation.

A critical doctrine at the time was they were held back by trade unions and soft economic policy that encouraged inflation. The proof that inflation was so damaging is scant and beyond the print, coal, rail and motor industries, British trade unions were pretty weak and pliant. What instead held these companies back was the evaporation of the guaranteed markets of empire. Second, a short-term, gentlemanly, disengaged financial system was unable to mobilise resource behind these companies and their greater purpose as imperial markets shrank. That wasn’t widely understood then – and certainly not now. Instead, the economic problem was defined as pampered, unionised workers, a view further entrenched by an avalanche of free-market economics from the US. Worker privileges and rights must cease.

So to the firm of today. The new model firm no longer has workers who are members of the organisation in a relationship of mutual respect and shared mission with committed, long-term owners; rather, the new ownerless corporation with its tourist shareholders employs contractors who have to pay for benefits themselves and can be hired and fired at will.

They are throwaway people, middle-class workers at risk as much as their working-class peers. Unions are not welcome; pension benefits are scaled back; sickness, paternity and maternity benefits are pitched at the regulatory minimum. Last week, the Citizens Advice Bureau said it estimated that 460,000 people nationwide had been defined by employers as self-employed (and thus entitled to no company benefits), even though they worked regularly for one employer, often in office roles. It is the same approach that has delivered 1.4 million zero-hours contracts. All this allegedly is to serve growth. Except over the last 20 years, growth, productivity and innovation in both Britain and America have collapsed. These new firms whose only purpose is short-term profit with contractualised workforces turn out to be poor creators of long-term value. The exceptions, paradoxically, are the great hi-tech companies such as Amazon, Google, Apple and Facebook.

The alchemy of their success is they combine innovative technology, produce at continental scale, invest heavily and commit to a great purpose, usually because of the powerful personal commitment of the founder. Bezos may have constructed a Darwinian work environment but it is all “to be the Earth’s most customer-centric company”. He has invested hugely to achieve that end, but his workplaces, by contrast, seem terrible.

But even Bezos does not want to be depicted as an employer with no moral centre: he urged his employees to read the offending article and refer examples of bad practice to his human resources department.

Ultimately, long-term value creation can’t be done by treating your workforces as cattle. It’s the great debate about today’s capitalism. It would be a triumph if it was taken more seriously in Britain.

Friday, 22 August 2014

For a shining example of trade unionism, look no further than football

The Professional Footballers’ Association shows what can be achieved when everyone is working for the same goal

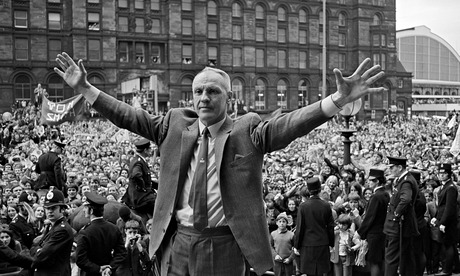

“The socialism I believe in is everybody working for the same goal and everybody having a share in the rewards. That’s how I see football, that’s how I see life.” So said Bill Shankly, legend of Liverpool Football Club.

Liverpool fans (like me) who lovingly quote Shankly’s words are often told that we’re idealists; that his egalitarian vision is a far cry from the reality of contemporary football. But although socialism is going a bit far, Shankly may have had a point: because it is in British professional football that we find one of the most successful examples of modern trade unionism.

The Professional Footballers’ Association (PFA) is the only trade union in the country to have 100% membership, and its principle success lies in its remarkable collective bargaining agreement, which applies to all professional footballers. It offers players numerous protections, including sickness arrangements, insurance in case of injury, post-retirement obligations and disciplinary proceedings (in which the PFA plays a central part).

Collective bargaining is the mechanism that allows workers to negotiate with employers as a whole workforce instead of as individuals. It puts workers in a more powerful position to obtain better terms and conditions, and can establish industry standards. Areport released this week by the Institute for Employment Rights demonstrates that collective bargaining can reduce pay inequality, narrow the gender pay gap, and protect employees from wage cuts during times of financial crisis. It can also reduce income inequality across society. The report notes: “When collective bargaining coverage began to fall in the 1980s, average wages also fell. As the number of workers covered by collective agreements has continued to decline, income inequality has rapidly grown.”

As only one in four British workers are now covered by collective bargaining, the PFA’s agreement is quite exceptional. In practice it means that all footballers are subject to exactly the same terms and conditions, regardless of whom they play for: a player for Luton Town will be treated in exactly the same way by his club as Cesc Fábregas will be for Chelsea. The ethos behind it is that every player puts in the same 90 minutes and should be valued in the same way.

In this respect, the PFA’s agreement is about building solidarity between leagues: the players in better negotiating positions (such as Fábregas) use their power, through the PFA, to improve the terms and conditions of every union member. As the career of a professional footballer lasts an average of just eight years, good terms and conditions are vital – especially for the players who are not in the position to earn top salaries or be offered sponsorship deals.

The PFA has fought to establish itself as an essential part of the professional game and is involved in all key decisions on regulations and how football is run in England. It recently played a pivotal role in ensuring that Portsmouth survived after its financial troubles, which was made possible by applying the “football creditors rule”. This rule is a protection negotiated by the union, which prioritises the players as creditors and imposes an obligation on any new owners to work with the union and honour existing contracts. As a result of this regulation and the solidarity of the players, every one of the 60 clubs that have gone into administration have survived, and remain an integral part of their communities.

Contradicting some employers who seek to undermine the strength of trade unions in workplaces, the PFA has demonstrated that unions – and by extension, workers themselves – are an essential component of industry, and can be good for employers too if they are trusted to take an active role in negotiations.

The case of Portsmouth FC begs the question of what other businesses might have survived administration during the past four years of recession if all unions were afforded the same level of trust that the PFA has been. Of course, the PFA is helped by the fact that footballers’ skills are very specific, but there is no reason why other industries can’t emulate its success by promoting trade unions in the workplace. Not doing so forces workers into a battle with employers, which doesn’t seem beneficial to either party.

What I find so extraordinary about the PFA is that it contradicts rightwing arguments that collective bargaining and trade unions are bad for business. When Governor Scott Walker outlawed collective bargaining in Wisconsin in 2012, he said: “The action today will help ensure Wisconsin has a business climate.”

We’ve been told for so long that better trade union rights will destroy the economy, and yet here is evidence of the benefits of strong trade unions being beamed into the living rooms of millions of people every weekend. As Nick Cusack, assistant chief executive of the PFA, puts it: “The PFA is the players’ greatest supporter. It shows trade unions can achieve a great deal of protections for workers. We’d like to see similar protections for workers across all industries.”

So there you have it. If you’re thinking of approaching your manager to get a better deal on your sick leave, think again. You might be better off talking to Wayne Rooney.

Tuesday, 1 July 2014

The real enemies of press freedom are in the newsroom

The principal threat to expression comes not from state regulation but from censorship by editors and proprietors

‘A political monoculture afflicts much of the press. Reports that might reveal a different side of the story remain unwritten.' Photograph: Tetra Images/Corbis

Three hundred years of press freedom are at risk, the newspapers cry. The government's proposed press regulator, they warn, threatens their independence. They have a respectable case, when you can extract it from the festoons of sticky humbug. Because of the shocking failures, so far, of self-regulation, I'm marginally in favour of the state solution. But I can also see the dangers.

Those who cry loudest against the regulator, however, recognise only one kind of freedom. In countries such as ours, the principal threat to freedom of expression comes not from government but from within the media. Censorship, in most cases, happens in the newsroom.

No newspaper has been more outspoken about what it calls "a chill over press freedom" than the Daily Mail. Though I agree with almost nothing it says, I would defend its freedom from state censorship as fiercely as I would defend the Guardian's. But, to judge by what it publishes, within the paper there is no freedom at all. There is just one line – echoed throughout its pages – on Europe, social security, state spending, tax, regulation, immigration, sentencing, trade unions and workers' rights. Labour is always too far to the left, even when it stands for nothing at all. Witness the self-defeating headline on Monday: "Red Ed 'won't unveil any policies in case they scare off voters'." Ed is red even when he's grey.

This suggests either that any article offering dissenting views is purged with totalitarian rigour, or general secretary Paul Dacre's terrified minions, knowing what is expected of them, never make such mistakes in the first place.

A similar political monoculture afflicts much of the press. Reports that might reveal a different side of the story remain unwritten. A free market in news is not the same as a free press, unless freedom is defined so narrowly that it refers only to the power of government, rather than to the power of money.

The monomania of the proprietors – or the editors they appoint in their own image – is compounded by an insidious, incestuous culture. The hacking trial revealed a world, as Suzanne Moore notes, of "sleepovers, dinners, flowers and presents ... in which genuine friendship is replaced by nightmare networking". A world in which one prime minister becomes godfather to a proprietor's child and another borrows an editor's horse, and an industry that is supposed to hold power to account brokers a seamless marriage between loot and boot.

On Mount Olympus, the gods pronounce upon issues that afflict only mortals: columnists with private-health plans support the savaging of the NHS; editors who educate their children privately heap praise upon Michael Gove, knowing that their progeny won't suffer his assault on state schools.

It doesn't matter, the defenders of these papers say: there are plenty of outlets, so balance can be found across the spectrum. But the great majority of papers, local as well as national, are owned by exceedingly rich people or their companies, and reflect their views. The owners, in the words of Max Hastings, once editor of the Daily Telegraph, are members of "the rich men's trade union", who "feel an instinctive sympathy for fellow multimillionaires". The field as a whole is unbalanced.

So pervasive are these voices that they seem to dominate even outlets they do not own. As Robert Peston, the BBC's economics editor, said last month, BBC News "is completely obsessed by the agenda set by newspapers ... if we think the Mail and Telegraph will lead with this, we should. It's part of the culture."

An analysis by researchers at Cardiff University found a deep and growing bias in the BBC in favour of bosses and against trade unions: five to one on the 6 o'clock news in 2007; 19 to one in 2012. Coverage of the banking crisis – caused by bankers – was overwhelmingly dominated, another study shows, by interviews with, er, bankers. As a result there was little serious challenge to their demand for bailouts and their resistance to regulation. Mike Berry, who conducted the research, says the BBC "tends to reproduce a Conservative, Eurosceptic, pro-business version of the world".

Last week, a brilliant and popular columnist for the Times, Simon Barnes, was sacked after 32 years. He was told that the paper could no longer afford his wages. But he wondered whether it might have something to do with the fierce campaign he's been waging against the owners of grouse moors, who have been wiping out the rare hen harriers that eat their quarry. It seems at first glance ridiculous: why would someone be sacked for grousing about grouse? But after experiencing the furious seigneurial affront with which a former senior editor at the Times, Magnus Linklater, responded to my enquiries about his 4,000-acre estate in Scotland and his failure to declare this interest while excoriating the RSPB for trying to protect hen harriers, I'm not so sure. This issue is of disproportionate interest to the rich men's trade union.

The two explanations might not be incompatible: if a paper owned by a crabby oligarch wanted to sack people for reasons of economy, it might look first at those engendering complaints among the owner's fellow moguls. The Times has yet to give me a comment.

Over the past few weeks, Private Eye has published several alarming claims about what it sees as censorship by the Telegraph on behalf of its advertisers. It says that extra stars have been added to film reviews, and that a story claiming HSBC had overstated its assets was spiked from on high so as not to offend the companies that pay the rent. The Telegraph told me: "We do not comment on inaccurate pieces from a satirical magazine like Private Eye."

Whatever the truth in these cases may be, it does not take journalists long to learn where the snakes lurk and the ladders begin. As the journalist Hannen Swaffer remarked long ago: "Freedom of the press ... is freedom to print such of the proprietor's prejudices as the advertisers don't object to." Yes, let's fight censorship: of the press and by the press.

Sunday, 19 May 2013

Exit Europe from the left

Most Britons dislike the European Union. If trade unions don't articulate their concerns, the hard right will

A protest in Brussels. 'Millions of personal tragedies of lost homes, jobs, pensions and services are testament to the sick joke of 'social Europe'.' Photograph: Thierry Roge/Reuters

For years the electorate has overwhelmingly opposed Britain's membership of the European Union – particularly those who work for a living. Yet while movements in other countries that are critical of the EU are led by the left, in Britain they are dominated by the hard right, and working-class concerns are largely ignored.

This is particularly strange when you consider that the EU is largely a Tory neoliberal project. Not only did the Conservative prime minister Edward Heath take Britain into the common market in 1973, but Margaret Thatcher campaigned to stay in it in the 1975 referendum, and was one of the architects of the Single European Act – which gave us the single market, EU militarisation and eventually the struggling euro.

After the Tories dumped the born-again Eurosceptic Thatcher, John Major rammed through the Maastricht treaty and embarked on the disastrous privatisation of our railways using EU directives – a model now set to be rolled out across the continent.

Even now, the majority of David Cameron's Tories will campaign for staying in the EU if we do get the referendum the electorate so clearly wants. And most of the left seems to be lining up alongside them. My union stood in the last European elections under the No2EU-Yes to Democracy coalition, which set out to give working people a voice that had been denied them by the political establishment. We also set out to challenge the rancid politics of the racist British National party, yet the BNP received far more media coverage. Today it is Ukip that is enjoying the media spotlight. Its rightwing Thatcherite rhetoric and assorted cranky hobby horses are a gift to a political establishment that seeks to project a narrow agenda of continued EU membership.

But the reality is that Ukip supports the EU agenda of privatisation, cuts and austerity. Nigel Farage's only problem with this government's assault on our public services is that it doesn't go far enough. Ukip opposes the renationalisation of our rail network as much as any Eurocrat. Yet Ukip has filled the political vacuum created when the Labour party and parts of the trade union movement adopted the position of EU cheerleaders, believing in the myth of "social Europe".

Social EU legislation, which supposedly leads to better working conditions, has not saved one job and is riddled with opt-outs for employers to largely ignore any perceived benefits they may bring to workers. But it is making zero-hour contracts and agency-working the norm while undermining collective bargaining and full-time, secure employment. Meanwhile, 10,000 manufacturing jobs in the East Midlands still hang in the balance because EU law demanded that the crucial Thameslink contract go to Siemens in Germany rather than Bombardier in Derby.

Today, unemployment in the eurozone is at a record 12%. In the countries hit hardest by the "troika" of banks and bureaucrats, youth unemployment tops 60% and the millions of personal tragedies of lost homes, jobs, pensions and services are testament to the sick joke of "social Europe".

The raft of EU treaties are, as Tony Benn once said, nothing more than a cast-iron manifesto for capitalism that demands the chaos of the complete free movement of capital, goods, services and labour. It is clear that Greece, Spain, Cyprus and the rest need investment, not more austerity and savage cuts to essential public services, but, locked in the eurozone, the only option left is exactly that.

What's more, the EU sees the current crisis as an opportunity to speed up its privatisation drive. Mass unemployment and economic decline is a price worth paying in order to impose structural adjustment in favour of monopoly capitalism.

In Britain and across the EU, healthcare, education and every other public service face the same business model of privatisation and fragmentation. Indeed, the clause in the Health and Social Care Act demanding privatisation of every aspect of our NHS was defended by the Lib Dems on the basis of EU competition law.

But governments do not have to carry out such EU policies: they could carry out measures on behalf of those who elect them. That means having democratic control over capital flows, our borders and the future of our economy for the benefit of everyone.

The only rational course to take is to leave the EU so that elected governments regain the democratic power to decide matters on behalf of the people they serve.

Wednesday, 6 March 2013

If bankers leave the country, it would be no loss

Ignore their howls of protest.

They took home unheard of sums. Only in Britain do ministers dance to their tune. But public fury cannot be defied for ever

Illustration by Belle Mellor

The peasants are revolting across Europe. They want bankers' blood and mean to get it. Until now, public response to the credit crunch has been one of general bafflement and wrist-slapping. The banks persuaded the world it was all an act of fate. As it was, they were too big to fail and their leaders too saintly to atone for it. For four years, British banks were showered with nearly half a trillion pounds of public and printed money. They duly recovered and stayed rich, while everyone else went poor.

The worm has turned. The banks and government alike have failed to deliver recovery. The people want revenge, and have found it – of all places – in the European parliament. It has declared that EU bankers cannot get bonuses bigger than their salaries, or twice as big if shareholders approve. This applies wherever EU bankers work, and to any overseas banker working in the EU.

Meanwhile, a Swiss referendum now requires top executives to seek explicit shareholder approval for their pay, with a ban on golden hellos and goodbyes. The Netherlands is talking of a tighter 20% cap on bonuses. Even laissez-faire Britain has seen the National Association of Pension Funds demand that boards keep executive pay rises down to inflation.

Europe's once omnipotent banking lobby has been all but neutered by the scale of scandal. The German government caved in to the EU parliament under pressure from the opposition Social Democrats. This was after the Libor scandal revealed Deutsche Bank cutting one trader's bonus by £34m, thus implying a staggering original sum. The Swiss campaign was kicked into life by the drugs firm Novartis giving its departing chairman a $76m gift. Some 68% of Swiss voted for the new curb.

Only in Britain do ministers still dance to the bankers' tune. Last month RBS executives brushed aside their state shareholder and paid themselves £600m in bonuses after posting a £5bn loss. Loss-making Lloyds dipped into its till and gave senior staff an extra £365m. Money-laundering HSBC announced 78 of its London executives would take home more than £1m each. They all say bonuses were unrelated to fines or losses, but they always say that. George Osborne was humiliated in Brussels on Tuesday by having to plead their fruitless cause.

Last year the City of London's much-heralded "shareholder spring" got nowhere. Revolts against executive pay at WPP, Barclays, Trinity Mirror and elsewhere had little noticeable impact. While overall pay stagnated, that of top executives rose 12%. Opinion polls showed the public overwhelmingly hostile to top pay. Only the government and the London mayor stand between the very rich and a furious public. The peasants' revolt means that even British ministers cannot defy opinion for ever.

The reality is that the banking community has allowed this thirst for revenge to build up for over four years, and it just did not care. Ever since the 1980s and financial deregulation, the profession took home sums of money unheard of in any other line of work.

This had nothing to do with free markets, except within a tight group of high-rolling traders. Modern bankers derive "economic rent" from exploiting oligopolistic cartels in financial services, with shareholders kept at one remove. The astronomical traders' bonuses are asymmetric returns on cash that properly belongs to depositors and shareholders whose money bears the risk. In any other business such bonuses would be regarded as theft from the firm.

For four years the British government – Labour and the coalition – huffed and puffed but was too terrified of the banks to act. Regulators were suborned by lobbyists and ministers, their offices packed with seconded bankers, and did as they were told. They gave huge sums to the banks in the belief that this was benefiting the demand economy. In Britain, some £400bn of cash was "pumped into the economy" via the banks. They merely traded or hoarded it, to their ever greater enrichment. The money vanished. A thousand pounds handed to every British citizen would have had more impact on the economy.

Last year, as if learning nothing, the Treasury gave the banks another £80bn to boost business and mortgage lending. This week it was predictably revealed that lending to small businesses actually fell as result. It was like giving money to a drunk and telling him to support his children. Never in the history of money can policy have been so glaringly inept. The banks laughed.

No trade unions are fiercer in defending their interests than the rich professions. As we saw this week with lawyers, cut their largesse and they threaten to take it out on the poor, the economy, the government, everyone. The banks howl that the bonus cap means their greed will go "offshore". This seems exaggerated. But the EU curbs could possibly see the start of the high-rollers moving out of over-regulated Europe towards the Americas and Asia.

This would not be wholly good news for Britain: finance has been the boom industry of the past quarter-century. But more likely is that the more toxic activities will go, and that is no loss. Either way, the banks have themselves to blame. They flew their golden wings too near the sun, and rage has melted them. They have only one plea on their side. The culture of greed in the City was nothing to the culture of ineptitude at the Bank of England and the Treasury. They pumped out the money. Never in British economic history can so much have been so wasted on so fruitless a cause. And still no hint of remorse.

Sunday, 3 February 2013

Inequality for All – another Inconvenient Truth?

The powerful documentary Inequality for All was an unexpected hit at the recent Sundance film festival, arguing that US capitalism has fatally abandoned the middle classes while making the super-rich richer. Can its star, economist Robert Reich, do for economics what Al Gore did for the environment?

Former US labour secretary Robert Reich at an Occupy Los Angeles rally in 2011. Photograph: David Mcnew/Getty Images

In one sense, Inequality for All is absolutely the film of the moment. We are living through tumultuous times. The economy has tanked. Austerity has cut a swath through the country. We're on the verge of a triple-dip recession. And, in another, parallel universe, a small cohort of alien beings – or as we know them, bankers – are currently engaged in trying to figure out what to spend their multimillion-pound bonuses on. Who wouldn't want to know what's going on? Or how it happened? Or why? Or if it is really true that the next generation down is well and truly shafted?

And yet… what sucker would try to make a film about it? It's not exactly Skyfall. Where would you even start? Because there are some films that practically beg to be made. And then there's Inequality for All; the kind of film that you can't quite believe that anybody, ever, considered a good idea, let alone had the passion and commitment to give it two years of their life.

How did you even come up with the idea of making a film about economics? I ask the director Jacob Kornbluth. "I know! People would roll their eyes when I told them. They'd say it's a terrible idea for a film." On paper it is, indeed, a terrible idea. A 90-minutedocumentary on income inequality: or why the rich have got richer and the rest of us haven't (I say "us" because although it's focused on America, we're snapping at their heels) and which traces a line back to the 1970s, when things stopped getting better for the vast majority of ordinary working people and started getting worse.

"It always sounded so dry," says Kornbluth. "But then I'd tell people it's An Inconvenient Truth for the economy and they'd go, Ah!"

In fact, Inequality for All, which premiered at the Sundance film festival a fortnight ago, is anything but dry. It won not just rave reviews but also the special jury prize and a major cinema distribution deal, and while it owes an obvious debt to Al Gore's An Inconvenient Truth, it is, in many ways, a much better, more human and surprising film. Not least because, incredibly enough, it's actually pretty funny. And, in large part, this is down to its star, Robert Reich.