'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Amazon. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Amazon. Show all posts

Saturday, 30 September 2023

Sunday, 19 September 2021

Thursday, 26 November 2020

Monday, 6 April 2020

We're not all in coronavirus together

‘The virus does not discriminate,” suggested Michael Gove after both Boris Johnson and the health secretary, Matt Hancock, were struck down by Covid-19. But societies do. And in so doing, they ensure that the devastation wreaked by the virus is not equally shared writes Kenan Malik in The Guardian

We can see this in the way that the low paid both disproportionately have to continue to work and are more likely to be laid off; in the sacking of an Amazon worker for leading a protest against unsafe conditions; in the rich having access to coronavirus tests denied to even most NHS workers.

But to see most clearly how societies allow the virus to discriminate, look not at London or Rome or New York but at Delhi and Johannesburg and Lagos. Here, “social distancing” means something very different than it does to Europeans or Americans. It is less about the physical space between people than the social space between the rich and poor that means only the privileged can maintain any kind of social isolation.

In the Johannesburg township of Alexandra, somewhere between 180,000 and 750,000 people live in an estimated 20,000 shacks. Through it runs South Africa’s most polluted river, the Jukskei, whose water has tested positive for cholera and has run black from sewage. Makoko is often called Lagos’s “floating slum” because a third of the shacks are built on stilts over a fetid lagoon. No one is sure how many people live there, but it could be up to 300,000. Dharavi, in Mumbai, is the word’s largest slum. Like Makoko and Alexandra, it nestles next to fabulously rich areas, but the million people estimated to live there are squashed into less than a square mile of land that was once a rubbish tip.

In such neighbourhoods, what can social distancing mean? Extended families often live in one- or two-room shacks. The houses may be scrubbed and well kept but many don’t have lavatories, electricity or running water. Communal latrines and water points are often shared by thousands. Diseases from diarrhoea to typhoid stalked such neighbourhoods well before coronavirus.

FacebookTwitterPinterest People in their shanties at Dharavi during the coronavirus lockdown in Mumbai. Photograph: Rajanish Kakade/AP

South Africa, Nigeria and India have all imposed lockdowns. Alexandra and Dharavi have both reported their first cases of coronavirus. But in these neighbourhoods, the idea of protecting oneself from coronavirus must seem as miraculous as clean water.

Last week, tens of thousands of Indian workers, suddenly deprived of the possibility of pay, and with most public transport having been shut down, decided to walk back to their home villages, often hundreds of miles away, in the greatest mass exodus since partition. Four out of five Indians work in the informal sector. Almost 140 million, more than a quarter of India’s working population, are migrants from elsewhere in the country. Yet their needs had barely figured in the thinking of policymakers, who seemed shocked by the actions of the workers.

India’s great exodus shows that “migration” is not, as we imagine in the west, merely external migration, but internal migration, too. Internal migrants, whether in India, Nigeria or South Africa, are often treated as poorly as external ones and often for the same reason – they are not seen as “one of us” and so denied basic rights and dignities. In one particularly shocking incident, hundreds of migrants returning to the town of Bareilly, in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, were sprayed by officials with chemicals usually used to sanitise buses. They might as well have been vermin, not just metaphorically but physically, too.

All this should make us think harder about what we mean by “community”. In Britain, the pandemic has led to a flowering of social-mindedness and community solidarity. Where I live in south London, a mutual aid group has sprung up to help self-isolating older people. The food bank has gained a new throng of volunteers. Such welcome developments have been replicated in hundreds of places around the country.

FacebookTwitterPinterest South African National Defence Force soldiers enforce lockdown in Johannesburg’s Alexandra township on 28 March 2020. Photograph: Luca Sola/AFP via Getty Images

But the idea of a community is neither as straightforward nor as straightforwardly good as we might imagine. When Donald Trump reportedly offers billions of dollars to a German company to create a vaccine to be used exclusively for Americans, when Germany blocks the export of medical equipment to Italy, when Britain, unlike Portugal, refuses to extend to asylum seekers the right to access benefits and healthcare during the coronavirus crisis, each does so in the name of protecting a particular community or nation.

The rhetoric of community and nation can become a means not just to discount those deemed not to belong but also to obscure divisions within. In India, Narendra Modi’s BJP government constantly plays to nationalist themes, eulogising Mother India, or Bhārat Mata. But it’s a nationalism that excludes many groups, from Muslims to the poor. In Dharavi and Alexandra and Makoko, and many similar places, it will not simply be coronavirus but also the willingness of the rich, both in poor countries and in wealthier nations, to ignore gross inequalities that will kill.

In Britain in recent weeks, there has been a welcome, belated recognition of the importance of low-paid workers. Yet in the decade before that, their needs were sacrificed to the demands of austerity, under the mantra of “we’re all in it together”. We need to beware of the same happening after the pandemic, too, of the rhetoric of community and nation being deployed to protect the interests of privileged groups. We need to beware, too, that in a world that many insist will be more nationalist, and less global, we don’t simply ignore what exists in places such as Alexandra and Makoko and Dharavi.

“We’re all at risk from the virus,” observed Gove. That’s true. It is also true that societies, both nationally and globally, are structured in ways that ensure that some face far more risk than others – and not just from coronavirus.

We can see this in the way that the low paid both disproportionately have to continue to work and are more likely to be laid off; in the sacking of an Amazon worker for leading a protest against unsafe conditions; in the rich having access to coronavirus tests denied to even most NHS workers.

But to see most clearly how societies allow the virus to discriminate, look not at London or Rome or New York but at Delhi and Johannesburg and Lagos. Here, “social distancing” means something very different than it does to Europeans or Americans. It is less about the physical space between people than the social space between the rich and poor that means only the privileged can maintain any kind of social isolation.

In the Johannesburg township of Alexandra, somewhere between 180,000 and 750,000 people live in an estimated 20,000 shacks. Through it runs South Africa’s most polluted river, the Jukskei, whose water has tested positive for cholera and has run black from sewage. Makoko is often called Lagos’s “floating slum” because a third of the shacks are built on stilts over a fetid lagoon. No one is sure how many people live there, but it could be up to 300,000. Dharavi, in Mumbai, is the word’s largest slum. Like Makoko and Alexandra, it nestles next to fabulously rich areas, but the million people estimated to live there are squashed into less than a square mile of land that was once a rubbish tip.

In such neighbourhoods, what can social distancing mean? Extended families often live in one- or two-room shacks. The houses may be scrubbed and well kept but many don’t have lavatories, electricity or running water. Communal latrines and water points are often shared by thousands. Diseases from diarrhoea to typhoid stalked such neighbourhoods well before coronavirus.

FacebookTwitterPinterest People in their shanties at Dharavi during the coronavirus lockdown in Mumbai. Photograph: Rajanish Kakade/AP

South Africa, Nigeria and India have all imposed lockdowns. Alexandra and Dharavi have both reported their first cases of coronavirus. But in these neighbourhoods, the idea of protecting oneself from coronavirus must seem as miraculous as clean water.

Last week, tens of thousands of Indian workers, suddenly deprived of the possibility of pay, and with most public transport having been shut down, decided to walk back to their home villages, often hundreds of miles away, in the greatest mass exodus since partition. Four out of five Indians work in the informal sector. Almost 140 million, more than a quarter of India’s working population, are migrants from elsewhere in the country. Yet their needs had barely figured in the thinking of policymakers, who seemed shocked by the actions of the workers.

India’s great exodus shows that “migration” is not, as we imagine in the west, merely external migration, but internal migration, too. Internal migrants, whether in India, Nigeria or South Africa, are often treated as poorly as external ones and often for the same reason – they are not seen as “one of us” and so denied basic rights and dignities. In one particularly shocking incident, hundreds of migrants returning to the town of Bareilly, in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, were sprayed by officials with chemicals usually used to sanitise buses. They might as well have been vermin, not just metaphorically but physically, too.

All this should make us think harder about what we mean by “community”. In Britain, the pandemic has led to a flowering of social-mindedness and community solidarity. Where I live in south London, a mutual aid group has sprung up to help self-isolating older people. The food bank has gained a new throng of volunteers. Such welcome developments have been replicated in hundreds of places around the country.

FacebookTwitterPinterest South African National Defence Force soldiers enforce lockdown in Johannesburg’s Alexandra township on 28 March 2020. Photograph: Luca Sola/AFP via Getty Images

But the idea of a community is neither as straightforward nor as straightforwardly good as we might imagine. When Donald Trump reportedly offers billions of dollars to a German company to create a vaccine to be used exclusively for Americans, when Germany blocks the export of medical equipment to Italy, when Britain, unlike Portugal, refuses to extend to asylum seekers the right to access benefits and healthcare during the coronavirus crisis, each does so in the name of protecting a particular community or nation.

The rhetoric of community and nation can become a means not just to discount those deemed not to belong but also to obscure divisions within. In India, Narendra Modi’s BJP government constantly plays to nationalist themes, eulogising Mother India, or Bhārat Mata. But it’s a nationalism that excludes many groups, from Muslims to the poor. In Dharavi and Alexandra and Makoko, and many similar places, it will not simply be coronavirus but also the willingness of the rich, both in poor countries and in wealthier nations, to ignore gross inequalities that will kill.

In Britain in recent weeks, there has been a welcome, belated recognition of the importance of low-paid workers. Yet in the decade before that, their needs were sacrificed to the demands of austerity, under the mantra of “we’re all in it together”. We need to beware of the same happening after the pandemic, too, of the rhetoric of community and nation being deployed to protect the interests of privileged groups. We need to beware, too, that in a world that many insist will be more nationalist, and less global, we don’t simply ignore what exists in places such as Alexandra and Makoko and Dharavi.

“We’re all at risk from the virus,” observed Gove. That’s true. It is also true that societies, both nationally and globally, are structured in ways that ensure that some face far more risk than others – and not just from coronavirus.

Monday, 9 December 2019

Friday, 7 September 2018

Is this good customer service from Amazon?

by Girish Menon

Amazon's Jeff Bezos, who claims excellent customer service as his motto, should be able to answer this one.

On July 10, 2018 I ordered a book from Amazon India, It was to be delivered only after three weeks. An Amazon courier delivered the book and I gave him the money expecting the packet to be the real goods. It wasn't. I had to then run around and call Amazon to get the real book. They collected their original material and told me they'd deliver the goods after another three weeks. They have not yet delivered the book. When I spoke to myriads of Amazon officials all I requested them was to send me the book to my new address. They refused. All they were willing to do is to give me a refund. Is this good customer service?

It is now nearly two months since I placed my order. Amazon still hold my money and refuse to deliver the goods to my new address. I have spent over three hours complaining and am none the wiser.

-----

Amazon's Jeff Bezos, who claims excellent customer service as his motto, should be able to answer this one.

On July 10, 2018 I ordered a book from Amazon India, It was to be delivered only after three weeks. An Amazon courier delivered the book and I gave him the money expecting the packet to be the real goods. It wasn't. I had to then run around and call Amazon to get the real book. They collected their original material and told me they'd deliver the goods after another three weeks. They have not yet delivered the book. When I spoke to myriads of Amazon officials all I requested them was to send me the book to my new address. They refused. All they were willing to do is to give me a refund. Is this good customer service?

It is now nearly two months since I placed my order. Amazon still hold my money and refuse to deliver the goods to my new address. I have spent over three hours complaining and am none the wiser.

-----

Sunday, 5 August 2018

The empty rituals of daily lives

Tabish Khair in The Hindu

Just as religious rituals move the practitioner away from the immensity of faith, secular rituals move citizens’ attention away from real issues

Serious religious thinkers have tended to distinguish between ritual and religion. Some, of course, have distinguished between spirituality and religion too, mostly because they have associated religion with rituals.

Now, rituals have their uses, as long as we employ them in the full awareness that they are arbitrary and man-made. This applies to secular matters as well as religious ones: I like my ritual of a morning cup of coffee with a biscuit or two, but I do not assume that this is god-ordained or that my day will not commence unless I have my cup of coffee. So, I am not talking of rituals of this sort. I am talking of rituals that are made ‘essential’ to either religion or secular life.

The matter with religion is clear enough. The reason why religious but nonconforming thinkers, like Kabir, railed against rituals was that they perceived how rituals are used, in the name of religion, to control, influence and exploit people. They also felt that rituals are worldly matters and have nothing to do with the divine. The priestly classes insist on rituals, as if god would care about the colour of your dress, the posture of your prayer, the number of your beads, etc. Rituals proliferate in religions because they allow the priestly classes to control and exploit ordinary believers. Instead of being used as an option, the coffee cup ritual becomes a necessity imposed on the ordinary believer, often at great cost.

Rituals in secular life

This much is clear enough about religion, and explains why so many religious thinkers — apart from the accredited priestly classes, whether mullahs or pandits — tended to criticise rituals or blind observance of rituals. But how, you might be asking, do rituals work in the secular sphere? Because such rituals are not confined to religion. They also exist in secular life, and are used by various ‘priestly classes’ to mislead, control and exploit ordinary people. I suspect that basically religious people, conditioned to associate belief with rituals, are likely to be misled by rituals in secular life too.

A ritual in secular life is like a ritual in religion: it is demanding, obsessive, unavoidable, essential. It is the one thing that you ‘need’ to do in order to have a good life (in this world or the next, or both). Or so the priestly classes claim. Because when you really look at this ‘essential’ ritual, it falls apart. It is not necessary; you can do without it. You can understand the world in other ways, live your life differently. But no, the priestly classes claim, you have to practice this ritual — or you will suffer and probably be damned for all eternity!

Rituals of prosperity

Think of the rituals that we are surrounded by in ordinary secular life. Think, for instance, of all those economic figures trotted out by national economists in all countries to show that the nation is progressing. GNP. Average national income. The rising value of shares in the stock market. These are rituals of prosperity, because if you really look into them, they mean nothing. Or they mean nothing because they have been turned from actual, though limited, indicators into sweeping rituals: empty practices.

A rise in GNP, the average national income, or the share market can indicate some types of prosperity, but these are not enough — and they are misleading when trotted out in ritualistic fashion by politicians. In each case, there is a good chance that some people might be gaining and many more losing. Take the situation of Amazon: the company is thriving, but, at least in the U.S., it is reputed to offer its workers a very meagre wage package and unsatisfactory working conditions. To think that the profits being made by Amazon is percolating down to its workers is to make a mistake. But that is the mistake we make when we simply note the net value of Amazon or the rise in its shares. Such figures play the role of empty rituals.

With countries, the matter is even more complex, as the prosperity of a country depends on factors other than financial ones. Hence, politicians who give us general figures and averages, whether correct or not, are indulging in empty rituals.

Of course, figures are not the only rituals practiced by politicians in power, the apex of the secular priestly classes. For instance, it is a ritual to construct a highway without making a sustained effort to improve the existing highways, to create a super-city without a sustained effort to improve the urban infrastructure in existing cities, to raise the statue of a great leader and ignore the best aspects of his example.

These acts and decisions are rituals because they are empty and misleading. Just as a ritual in religion moves the practitioner away from the endless immensity of faith to a delusive shortcut, a ritual in secular life moves citizens’ attention away from all the real issues and offers a soupçon of misleading satisfaction. I fear that we Indians might or might not be a spiritual people, but we do have a certain tendency to indulge — and let others indulge — in empty rituals in religious as well as secular life.

Serious religious thinkers have tended to distinguish between ritual and religion. Some, of course, have distinguished between spirituality and religion too, mostly because they have associated religion with rituals.

Now, rituals have their uses, as long as we employ them in the full awareness that they are arbitrary and man-made. This applies to secular matters as well as religious ones: I like my ritual of a morning cup of coffee with a biscuit or two, but I do not assume that this is god-ordained or that my day will not commence unless I have my cup of coffee. So, I am not talking of rituals of this sort. I am talking of rituals that are made ‘essential’ to either religion or secular life.

The matter with religion is clear enough. The reason why religious but nonconforming thinkers, like Kabir, railed against rituals was that they perceived how rituals are used, in the name of religion, to control, influence and exploit people. They also felt that rituals are worldly matters and have nothing to do with the divine. The priestly classes insist on rituals, as if god would care about the colour of your dress, the posture of your prayer, the number of your beads, etc. Rituals proliferate in religions because they allow the priestly classes to control and exploit ordinary believers. Instead of being used as an option, the coffee cup ritual becomes a necessity imposed on the ordinary believer, often at great cost.

Rituals in secular life

This much is clear enough about religion, and explains why so many religious thinkers — apart from the accredited priestly classes, whether mullahs or pandits — tended to criticise rituals or blind observance of rituals. But how, you might be asking, do rituals work in the secular sphere? Because such rituals are not confined to religion. They also exist in secular life, and are used by various ‘priestly classes’ to mislead, control and exploit ordinary people. I suspect that basically religious people, conditioned to associate belief with rituals, are likely to be misled by rituals in secular life too.

A ritual in secular life is like a ritual in religion: it is demanding, obsessive, unavoidable, essential. It is the one thing that you ‘need’ to do in order to have a good life (in this world or the next, or both). Or so the priestly classes claim. Because when you really look at this ‘essential’ ritual, it falls apart. It is not necessary; you can do without it. You can understand the world in other ways, live your life differently. But no, the priestly classes claim, you have to practice this ritual — or you will suffer and probably be damned for all eternity!

Rituals of prosperity

Think of the rituals that we are surrounded by in ordinary secular life. Think, for instance, of all those economic figures trotted out by national economists in all countries to show that the nation is progressing. GNP. Average national income. The rising value of shares in the stock market. These are rituals of prosperity, because if you really look into them, they mean nothing. Or they mean nothing because they have been turned from actual, though limited, indicators into sweeping rituals: empty practices.

A rise in GNP, the average national income, or the share market can indicate some types of prosperity, but these are not enough — and they are misleading when trotted out in ritualistic fashion by politicians. In each case, there is a good chance that some people might be gaining and many more losing. Take the situation of Amazon: the company is thriving, but, at least in the U.S., it is reputed to offer its workers a very meagre wage package and unsatisfactory working conditions. To think that the profits being made by Amazon is percolating down to its workers is to make a mistake. But that is the mistake we make when we simply note the net value of Amazon or the rise in its shares. Such figures play the role of empty rituals.

With countries, the matter is even more complex, as the prosperity of a country depends on factors other than financial ones. Hence, politicians who give us general figures and averages, whether correct or not, are indulging in empty rituals.

Of course, figures are not the only rituals practiced by politicians in power, the apex of the secular priestly classes. For instance, it is a ritual to construct a highway without making a sustained effort to improve the existing highways, to create a super-city without a sustained effort to improve the urban infrastructure in existing cities, to raise the statue of a great leader and ignore the best aspects of his example.

These acts and decisions are rituals because they are empty and misleading. Just as a ritual in religion moves the practitioner away from the endless immensity of faith to a delusive shortcut, a ritual in secular life moves citizens’ attention away from all the real issues and offers a soupçon of misleading satisfaction. I fear that we Indians might or might not be a spiritual people, but we do have a certain tendency to indulge — and let others indulge — in empty rituals in religious as well as secular life.

Saturday, 13 January 2018

The lesson for diagnosing a bubble

Tim Harford in The Financial Times

Here are three noteworthy pronouncements about bubbles.

“Prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” That was Professor Irving Fisher in 1929, prominently reported barely a week before the most brutal stock market crash of the 20th century. He was a rich man, and the greatest economist of the age. The great crash destroyed both his finances and his reputation.

“Those who sound the alarm of an approaching . . . crisis have somewhat exaggerated the danger.” That was a renowned commentator who shall remain nameless for now.

“We are currently showing signs of entering the blow-off or melt-up phase of this very long bull market.” That was investor Jeremy Grantham on January 3 this year. The normally bearish Mr Grantham mused that while shares seem expensive, historical precedents make it plausible that the S&P 500 will soar from present levels of around 2,700 to more than 3,500 before the crash occurs.

Mr Grantham’s speculation is striking because he has tended to be a savvy bubble watcher in the past. But as any toddler can attest, it is not an easy thing to catch one before it bursts.

There are two obvious ways to diagnose a bubble. One is to look at the fundamentals: if the price of an asset is unmoored from the cash flow it is likely to generate, that is a warning sign. (It is anyone’s guess what this implies for bitcoin, an asset that has no cash flow at all.)

The other approach is to look around: are people giddy with excitement? Can the media talk of little else? Are taxi drivers offering stock tips?

At the moment, however, these two approaches tell a different story about US stocks. They are expensive by most reasonable measures. But there are few other signs of speculative mania. The price rise has been steady, broad-based and was hardly the leading news of 2017. Given how expensive bonds are, it is hardly a surprise that stocks also seem pricey. No wonder investors and commentators are unsure what to say or do.

It seems all so much easier with hindsight: looking back, we can all enjoy a laugh at the Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, to borrow the title of Charles Mackay’s famous 1841 book, which chuckles at the South Sea bubble and tulip mania.

Yet even with hindsight things are not always clear. For example, I first became aware of the incipient dotcom bubble in the late 1990s, when a senior colleague told me that the upstart online bookseller Amazon.com was valued at more than every bookseller on the planet. A clearer instance of mania could scarcely be imagined.

But Amazon is worth much more today than at the height of the bubble, and comparing it with any number of booksellers now seems quaint. The dotcom bubble was mad and my colleague correctly diagnosed the lunacy, but he should still have bought and held Amazon stock.

Tales of the great tulip mania in 17th-century Holland seem clearer — most notoriously, the Semper Augustus bulb that sold for the price of an Amsterdam mansion.

“The population, even to its lowest dregs, embarked in the tulip trade,” sneered Mackay more than 200 years later.

But the tale grows murkier still. The economist Peter Garber, author of Famous First Bubbles, points out that a rare tulip bulb could serve as the breeding stock for generations of valuable flowers; as its descendants became numerous, one would expect the price of individual bulbs to fall.

Some of the most spectacular prices seem to have been empty tavern wagers by almost-penniless braggarts, ignored by serious traders but much noticed by moralists. The idea that Holland was economically convulsed is hard to support: the historian Anne Goldgar, author of Tulipmania, has been unable to find anyone who actually went bankrupt as a result.

It is easy to laugh at the follies of the past, especially if they have been exaggerated for the purposes of sermonising or for comic effect. Charles Mackay copied and exaggerated the juiciest reports he could find in order to get his point across. Then there is the matter of his own record as a financial guru. That comment, this time in full, “those who sound the alarm of an approaching railway crisis have somewhat exaggerated the danger”, was Mackay himself, writing in the Glasgow Argus in 1845, in full-throated support of the idea that the railway investment boom of the time would return a healthy profit to investors. It was, instead, a financial disaster. In the words of mathematician and bubble scholar Andrew Odlyzko, it was “by many measures the greatest technology mania in history, and its collapse was one of the greatest financial crashes”.

Oddly, Mackay barely mentions the railway mania in subsequent editions of his book — nor his own role as cheerleader. This is a lesson to us all. It’s very easy to scoff at past bubbles; it is not so easy to know how to react when one may — or may not — be surrounded by one.

Monday, 20 November 2017

The rise of dynamic and personalised pricing

Tim Walker in The Guardian

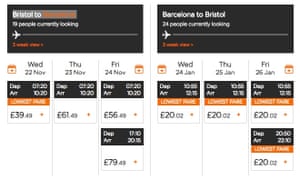

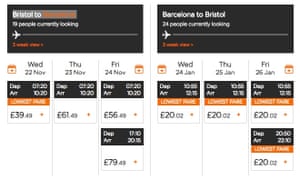

You wait 24 hours to book that flight, only to find it’s gone up by £100. You wait until Black Friday to buy that leather jacket and, sure enough, it’s been marked down. Today’s consumers are getting comfortable with the idea that prices online can fluctuate, not just at sale time, but several times over the course of a single day. Anyone who has booked a holiday on the internet is familiar with the concept, if not with its name. It’s known as dynamic pricing: when the cost of goods or services ebbs and flows in response to the slightest shifts in supply and demand, be it fresh croissants in the morning, a bargain TV or an Uber during a late-night “surge”.

Sports teams, entertainment venues and theme parks have started to use dynamic pricing methods, too, taking their cues from airlines and hotels to calibrate a range of ticketing deals that ensure they fill as many seats as possible. Last month, Regal, the US cinema chain, announced it would trial a form of dynamic ticket pricing at many of its multiplexes in 2018, in the hope of boosting its box office revenue. Digonex, one of the leading dynamic ticketing firms in the US, has consulted for Derby County and Manchester City football clubs in the UK. “In five years, dynamic pricing will be common practice in the attractions space,” says the company’s CEO, Greg Loewen. “The same goes for many other industries: movies, parking, tour operators.” Amazon, the world’s largest online retailer, tweaks countless prices every day. Savvy shoppers have learned to wait for bargains with the help of other sites such as CamelCamelCamel.com, which analyses Amazon price drops and lists the biggest. On a single day on Amazon.co.uk last week, those included a Samsung Galaxy S7 phone, down 14% from £510.29 to £439, and a pack of six 300g jars of Ovaltine, down 33% from £17.94 to £12.

Physical retailers can’t match the agility of their online rivals, not least because changing prices requires altering labels. But “smart shelves” – already common in European supermarkets – are coming to the UK, with digital price displays that allow retailers to offer deals at different times of day, along with information about the products. Sainsbury’s, Morrisons and Tesco have all trialled electronic pricing systems in select stores. Marks & Spencer conducted an electronic pricing experiment last year, selling sandwiches more cheaply during the morning rush hour to encourage commuters to buy their lunch early.

Toby Pickard, senior innovations and trends analyst at the grocery research firm IGD, says this new technology will benefit retailers by enabling them “to gain more data about the products they sell; for example, they can closely gauge how prices fluctuating throughout the day may alter shoppers’ purchasing habits, or if on-shelf digital product reviews increase sales.” IGD’s research suggests there is an appetite for this sort of tech from consumers, too. For example, says Pickard: “Four in 10 shoppers say they are interested in being alerted to offers on their phone while in-store.”

FacebookTwitterPinterest M&S experimented with pricing to encourage commuters to buy their lunch early. Photograph: Luke Johnson/Commissioned for The Guardian

Earlier this year, the Luxembourg-based computer firm SES took a majority stake in the Irish software firm MarketHub. Together, they are bringing data analysis and smart-shelf-style systems to some 14,000 stores in 54 countries including the UK. MarketHub says two Spar stores in London have succeeded in raising revenue and decreasing waste since introducing its technology. For the firm’s CEO Roy Horgan, though, there’s a big difference between what MarketHub offers and dynamic pricing per se. “I don’t see dynamic pricing happening in major retailers,” he says. “Supermarkets have huge, complicated logistics systems. They can’t react in real time to what’s going in their stores the way Amazon can. [Physical retailers] want to discount, to have more relevant deals, fewer promotions, better value and more customer loyalty. That’s not about changing the price of individual products, it’s more about changing deals.”

As examples, Horgan suggests offering cheap lunch deals in the morning (à la M&S), so that workers don’t have to queue up at lunchtime, or guiding shoppers with limited budgets to discounted ingredients for an evening meal. “That’s not dynamic pricing,” he says. “It’s just agile retail.”

A recent survey of US consumers by Retail Systems Research (RSR) found that 71% didn’t care for the idea of dynamic pricing, though millennials were more amenable to the concept, with 14% of younger shoppers saying they “loved” it. Perhaps that ought not to be surprising, given the younger generation’s greater familiarity with browsing for bargains online.

“Consumers always love it when they can get a great deal, and dynamic pricing isn’t just about raising prices – it often leads to lowering them,” says Loewen. “In general, we have found that when prices are transparent to consumers and they understand the ‘rules of the game’, they adapt to dynamic pricing fairly seamlessly and even embrace it.”

Simon Read, a money and personal finance writer, says: “If you’re desperate for an item and it’s the last available, you are likely to pay a premium when dynamic pricing comes into play.” But dynamic pricing can also play to the consumer’s benefit, he explains.

“The truth is that retailers want to flog their wares at whatever price they can get. If you want to take advantage of dynamic pricing, you’ll need to find out when retailers are desperate to sell. In bricks-and-mortar stores that means shopping at quiet times – in the morning – or waiting until closing time when grocers need to clear their shelves.” If you’re shopping online, Read says, research the normal price of an item before buying it, so as not to be caught out. “It’s also a good idea to leave things in your shopping basket at most online retailers rather than buying immediately. After a day or two, you will often get an email offering a decent reduction.”

Those consumers who are suspicious of dynamic pricing may also be confusing it with (the far more controversial) personalised pricing, whereby specific customers are asked to pay different amounts for the same product, tailored to what the retailer thinks they can and will spend – using personal data points that might one day include, for instance, our credit rating. In 2014, the US Department of Transportation approved a system allowing airlines and travel companies to collect passengers’ data to present them with “personalised offerings” based on their address, their marital status, their birthday and their travel history. It’s not hard to imagine that the fares you are offered might be higher than for others if, say, you live in an affluent postcode and your husband’s birthday is coming up.

Airlines use dynamic pricing on flight tickets. Photograph: Easyjet

In 2012, the travel site Orbitz was found to be adjusting its prices for users of Apple Mac computers, after finding that they were prepared to spend up to 30% more on hotel rooms than other customers. That same year, the Wall Street Journal revealed that the Staples website offered products at different pricesdepending on the user’s proximity to rival stores. In 2014, a study conducted by Northeastern University in Boston found that several major e-commerce sites such as Home Depot and Walmart were manipulating prices based on the browsing history of individual customers. “Most people assume the internet is a neutral environment like the high street, where the price you see is the same as the one everyone else sees,” says Ariel Ezrachi, director of the University of Oxford Centre for Competition Law and Policy. “But on the high street you’re anonymous; online, the seller has information about you, and about your other buying options.”

Dynamic pricing, says Ezrachi, is simply a way for businesses to respond nimbly to market trends, and thus is within the bounds of what consumers already accept as market dynamics. “Personalised pricing is much more problematic. It’s based on asymmetricity of information; it’s only possible because the shopper doesn’t know what information the seller has about them, and because the seller is able to create an environment where the shopper believes they are seeing the market price.”

The ethics of pricing based on an individual’s personal data are vexed: some consumers will find it manipulative and insist on its regulation; others may feel it’s fair – socially beneficial, even – to charge wealthy customers more for a product or service. “You will find people arguing in different directions,” Ezrachi says. Loyalty cards have long enabled supermarkets and other major retailers to offer personalised offers based on the spending habits of repeat customers. B&Q has tested electronic price tags that display different prices to different customers using information gleaned from their phones (the company made clear that their intention was to “reward regular customers with discounts”, not to raise the price for more profligate shoppers). In the US, Coca-Cola and Albertsons supermarkets have experimented with targeting shoppers in-store by sending personalised offers to their phones when they approach the soft drinks aisle in an Albertsons store.

Horgan resists the idea that supermarkets will embrace personalised pricing. “In the airline industry, we have more freedom, information and choice on airlines than we’ve ever had before, and that is all dynamic-pricing led. But nobody’s loyal to Ryanair; they’re loyal to the deal. Retail is different,” he says. “If I have five pounds in my pocket and a family of four to feed, I want to know I can generate a recipe that is nutritious for them, and I want an app that can navigate me around the store to find a deal on [the necessary ingredients]. To me, that is personalised retail. But any [bricks and mortar] retailer who charges different prices to different people for the same product is an idiot. They’re only going to lose loyalty.”

Loewen agrees that personalised pricing carries as many dangers as opportunities for retailers. “Consumers are more empowered and informed than ever before, and any pricing strategy that seeks to fool or mislead them is unlikely to be successful for long,” he says. Nevertheless, in the dawning era of dynamic pricing, personalised pricing and agile retailing, the days of fixed prices seem to be coming to an end. And although the technology may be more advanced, in some ways dynamic pricing is simply a return to the days long before supermarkets, when traders would judge how high or low a price to haggle from a customer based on factors as simple as the sound of their accent, or the cut of their cloak.

You wait 24 hours to book that flight, only to find it’s gone up by £100. You wait until Black Friday to buy that leather jacket and, sure enough, it’s been marked down. Today’s consumers are getting comfortable with the idea that prices online can fluctuate, not just at sale time, but several times over the course of a single day. Anyone who has booked a holiday on the internet is familiar with the concept, if not with its name. It’s known as dynamic pricing: when the cost of goods or services ebbs and flows in response to the slightest shifts in supply and demand, be it fresh croissants in the morning, a bargain TV or an Uber during a late-night “surge”.

Sports teams, entertainment venues and theme parks have started to use dynamic pricing methods, too, taking their cues from airlines and hotels to calibrate a range of ticketing deals that ensure they fill as many seats as possible. Last month, Regal, the US cinema chain, announced it would trial a form of dynamic ticket pricing at many of its multiplexes in 2018, in the hope of boosting its box office revenue. Digonex, one of the leading dynamic ticketing firms in the US, has consulted for Derby County and Manchester City football clubs in the UK. “In five years, dynamic pricing will be common practice in the attractions space,” says the company’s CEO, Greg Loewen. “The same goes for many other industries: movies, parking, tour operators.” Amazon, the world’s largest online retailer, tweaks countless prices every day. Savvy shoppers have learned to wait for bargains with the help of other sites such as CamelCamelCamel.com, which analyses Amazon price drops and lists the biggest. On a single day on Amazon.co.uk last week, those included a Samsung Galaxy S7 phone, down 14% from £510.29 to £439, and a pack of six 300g jars of Ovaltine, down 33% from £17.94 to £12.

Physical retailers can’t match the agility of their online rivals, not least because changing prices requires altering labels. But “smart shelves” – already common in European supermarkets – are coming to the UK, with digital price displays that allow retailers to offer deals at different times of day, along with information about the products. Sainsbury’s, Morrisons and Tesco have all trialled electronic pricing systems in select stores. Marks & Spencer conducted an electronic pricing experiment last year, selling sandwiches more cheaply during the morning rush hour to encourage commuters to buy their lunch early.

Toby Pickard, senior innovations and trends analyst at the grocery research firm IGD, says this new technology will benefit retailers by enabling them “to gain more data about the products they sell; for example, they can closely gauge how prices fluctuating throughout the day may alter shoppers’ purchasing habits, or if on-shelf digital product reviews increase sales.” IGD’s research suggests there is an appetite for this sort of tech from consumers, too. For example, says Pickard: “Four in 10 shoppers say they are interested in being alerted to offers on their phone while in-store.”

FacebookTwitterPinterest M&S experimented with pricing to encourage commuters to buy their lunch early. Photograph: Luke Johnson/Commissioned for The Guardian

Earlier this year, the Luxembourg-based computer firm SES took a majority stake in the Irish software firm MarketHub. Together, they are bringing data analysis and smart-shelf-style systems to some 14,000 stores in 54 countries including the UK. MarketHub says two Spar stores in London have succeeded in raising revenue and decreasing waste since introducing its technology. For the firm’s CEO Roy Horgan, though, there’s a big difference between what MarketHub offers and dynamic pricing per se. “I don’t see dynamic pricing happening in major retailers,” he says. “Supermarkets have huge, complicated logistics systems. They can’t react in real time to what’s going in their stores the way Amazon can. [Physical retailers] want to discount, to have more relevant deals, fewer promotions, better value and more customer loyalty. That’s not about changing the price of individual products, it’s more about changing deals.”

As examples, Horgan suggests offering cheap lunch deals in the morning (à la M&S), so that workers don’t have to queue up at lunchtime, or guiding shoppers with limited budgets to discounted ingredients for an evening meal. “That’s not dynamic pricing,” he says. “It’s just agile retail.”

A recent survey of US consumers by Retail Systems Research (RSR) found that 71% didn’t care for the idea of dynamic pricing, though millennials were more amenable to the concept, with 14% of younger shoppers saying they “loved” it. Perhaps that ought not to be surprising, given the younger generation’s greater familiarity with browsing for bargains online.

“Consumers always love it when they can get a great deal, and dynamic pricing isn’t just about raising prices – it often leads to lowering them,” says Loewen. “In general, we have found that when prices are transparent to consumers and they understand the ‘rules of the game’, they adapt to dynamic pricing fairly seamlessly and even embrace it.”

Simon Read, a money and personal finance writer, says: “If you’re desperate for an item and it’s the last available, you are likely to pay a premium when dynamic pricing comes into play.” But dynamic pricing can also play to the consumer’s benefit, he explains.

“The truth is that retailers want to flog their wares at whatever price they can get. If you want to take advantage of dynamic pricing, you’ll need to find out when retailers are desperate to sell. In bricks-and-mortar stores that means shopping at quiet times – in the morning – or waiting until closing time when grocers need to clear their shelves.” If you’re shopping online, Read says, research the normal price of an item before buying it, so as not to be caught out. “It’s also a good idea to leave things in your shopping basket at most online retailers rather than buying immediately. After a day or two, you will often get an email offering a decent reduction.”

Those consumers who are suspicious of dynamic pricing may also be confusing it with (the far more controversial) personalised pricing, whereby specific customers are asked to pay different amounts for the same product, tailored to what the retailer thinks they can and will spend – using personal data points that might one day include, for instance, our credit rating. In 2014, the US Department of Transportation approved a system allowing airlines and travel companies to collect passengers’ data to present them with “personalised offerings” based on their address, their marital status, their birthday and their travel history. It’s not hard to imagine that the fares you are offered might be higher than for others if, say, you live in an affluent postcode and your husband’s birthday is coming up.

Airlines use dynamic pricing on flight tickets. Photograph: Easyjet

In 2012, the travel site Orbitz was found to be adjusting its prices for users of Apple Mac computers, after finding that they were prepared to spend up to 30% more on hotel rooms than other customers. That same year, the Wall Street Journal revealed that the Staples website offered products at different pricesdepending on the user’s proximity to rival stores. In 2014, a study conducted by Northeastern University in Boston found that several major e-commerce sites such as Home Depot and Walmart were manipulating prices based on the browsing history of individual customers. “Most people assume the internet is a neutral environment like the high street, where the price you see is the same as the one everyone else sees,” says Ariel Ezrachi, director of the University of Oxford Centre for Competition Law and Policy. “But on the high street you’re anonymous; online, the seller has information about you, and about your other buying options.”

Dynamic pricing, says Ezrachi, is simply a way for businesses to respond nimbly to market trends, and thus is within the bounds of what consumers already accept as market dynamics. “Personalised pricing is much more problematic. It’s based on asymmetricity of information; it’s only possible because the shopper doesn’t know what information the seller has about them, and because the seller is able to create an environment where the shopper believes they are seeing the market price.”

The ethics of pricing based on an individual’s personal data are vexed: some consumers will find it manipulative and insist on its regulation; others may feel it’s fair – socially beneficial, even – to charge wealthy customers more for a product or service. “You will find people arguing in different directions,” Ezrachi says. Loyalty cards have long enabled supermarkets and other major retailers to offer personalised offers based on the spending habits of repeat customers. B&Q has tested electronic price tags that display different prices to different customers using information gleaned from their phones (the company made clear that their intention was to “reward regular customers with discounts”, not to raise the price for more profligate shoppers). In the US, Coca-Cola and Albertsons supermarkets have experimented with targeting shoppers in-store by sending personalised offers to their phones when they approach the soft drinks aisle in an Albertsons store.

Horgan resists the idea that supermarkets will embrace personalised pricing. “In the airline industry, we have more freedom, information and choice on airlines than we’ve ever had before, and that is all dynamic-pricing led. But nobody’s loyal to Ryanair; they’re loyal to the deal. Retail is different,” he says. “If I have five pounds in my pocket and a family of four to feed, I want to know I can generate a recipe that is nutritious for them, and I want an app that can navigate me around the store to find a deal on [the necessary ingredients]. To me, that is personalised retail. But any [bricks and mortar] retailer who charges different prices to different people for the same product is an idiot. They’re only going to lose loyalty.”

Loewen agrees that personalised pricing carries as many dangers as opportunities for retailers. “Consumers are more empowered and informed than ever before, and any pricing strategy that seeks to fool or mislead them is unlikely to be successful for long,” he says. Nevertheless, in the dawning era of dynamic pricing, personalised pricing and agile retailing, the days of fixed prices seem to be coming to an end. And although the technology may be more advanced, in some ways dynamic pricing is simply a return to the days long before supermarkets, when traders would judge how high or low a price to haggle from a customer based on factors as simple as the sound of their accent, or the cut of their cloak.

Monday, 30 October 2017

Big Tech and Amazon: too powerful to break up?

While Google, Facebook and Twitter are set for a grilling in Congress over Russia, it is the online retailer that is drawing intense scrutiny

David J Lynch in The Financial Times

Amazon executives will not be present on Tuesday when three other major internet companies endure a grilling before Congress. But it may just be a matter of time before Washington’s new appetite for regulating the digital economy reaches the e-commerce giant.

Amazon executives will not be present on Tuesday when three other major internet companies endure a grilling before Congress. But it may just be a matter of time before Washington’s new appetite for regulating the digital economy reaches the e-commerce giant.

Lawyers for Google, Facebook and Twitter will occupy this week’s spotlight in front of the Senate intelligence and judiciary committees, which are probing the companies’ unwitting role in Russia’s 2016 election meddling. Already, there is talk of legislation requiring them to disclose more about their operations.

The controversy over the industry’s dissemination of Russian “fake news” highlights a broader souring of attitudes toward the online platforms, triggered by unease over their sheer size and power, which spans the political spectrum. From progressives like Elizabeth Warren, Massachusetts senators, to Steve Bannon, President Donald Trump’s former chief strategist, who runs the nationalist media site Breitbart, there is growing support for reining in, or even breaking up, the digital groups that dominate the US economy.

“The worm has turned,” says Scott Galloway, a marketing professor at New York University and author of The Four: the Hidden DNA of Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google. “No doubt about it.”

Though unaffected by the Russia allegations Amazon — whose $136bn in revenues last year topped the combined sales of Google parent Alphabet and Facebook — is a target of demands for more assertive antitrust enforcement. Its dominance has also raised questions about whether existing legislation needs to be rewritten for the internet age.

The online retailer’s relentless expansion into new businesses, including groceries and small business lending, and its control of data on the millions of third-party vendors that use its sales platform, warehouses and delivery services, have some analysts likening it to a 21st century version of the corporate trusts such as Standard Oil that throttled American competition a century ago.

“Amazon has big antitrust problems in its future,” says Scott Cleland, a technology policy official in the George HW Bush administration and president of Precursor, a research consultancy. “If there is a minimally interested, fair-minded antitrust effort in the Trump administration, Amazon’s got trouble.”

For now, Mr Cleland’s remains a minority view. Most experts say the company has yet to engage in the classic anti-competitive behaviour that the antitrust laws are designed to prevent. Under the prevailing interpretation of this doctrine, which prizes consumer welfare above all else, champion price-cutter Amazon has little reason to worry. Indeed, US regulators this summer performed only a brief review before approving Amazon’s nearly $14bn acquisition of the upmarket grocer Whole Foods.

Amazon and the other platforms remain popular with consumers, thanks to their low prices or “free” services. But companies that were once seen as avatars of American innovation and achievement are now increasingly treated with scepticism. Mr Bannon has said that companies such as Google and Facebook are so essential to daily life that they should be regulated as public utilities.

The digital platforms “dominate the economy and their respective markets like few businesses in the modern era”, says the bipartisan New Center project of Republican William Kristol and Democrat Bill Galston. It notes that nearly half of all e-commerce passes through Amazon while Facebook controls 77 per cent of mobile social traffic and Google has 81 per cent of the search engine market.

The online retailer stands alone in its cross-market reach, dominating product search, hardware and cloud computing while also serving as an indispensable conduit for other vendors to reach consumers, says Mr Galloway. Last year, 55 per cent of product searches began on Amazon, topping Google.

“They’re winning at everything,” he says. “This company is firing on all 12,000 cylinders.”

Yet even as calls to break up the nation’s big banks after the global financial crisis have faded, talk that the digital giants have grown too large gets ever louder. The downside of economic concentration features prominently in the Democratic party’s “Better Deal” programme for the 2018 Congressional elections. It calls for an intensification in antitrust enforcement and blames stagnant wages, rising prices and disappointing growth on insufficient competition.

An anti-monopoly push will “almost certainly” be a major part of the 2020 presidential campaign, predicts Barry Lynn of the Open Markets initiative.

Silicon Valley’s tradition of funding the party could complicate the Democrats’ anti-monopoly push. In the 2016 election, the internet industry gave 74 per cent of its $12.3m in congressional campaign contributions to Democrats. Internet company executives and their corporate political action committees, which pool individual contributions in accord with the federal prohibition on direct corporate political spending, also gave Hillary Clinton’s campaign more than $6.3m while Mr Trump pulled in less than $100,000, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

Individuals and the PACs associated with Google parent Alphabet topped the industry’s list of total political contributors with $8.1m while Amazon ranked fourth with about $1.4m.

Amazon has moved a long way from its roots since launching two decades ago to sell books and nothing but books. Now, it sells just about everything to everybody: nearly 400m products including its own batteries, shirts and baby wipes. It operates a media studio and provides cloud computing space to customers such as the Central Intelligence Agency while running the Marketplace sales platform for other vendors, a delivery and logistics network and a payment service. The company Jeff Bezos launched in 1994 also now makes popular electronics, including the Kindle ereader and the Alexa voice-activated device.

Its growth has been astronomical. Amazon expects to record at least $173bn in annual sales this year — that would nearly double its 2014 figure. It employs 542,000 workers, more than twice its mid-2016 payroll, thanks in part to the Whole Foods deal, and its $1,100 share price has roughly doubled in just 20 months.

By almost any measure, Amazon is a fantastically successful company. Maybe too successful, its detractors say. Mr Trump has periodically suggested antitrust action against the online giant, saying of Mr Bezos last year: “He’s got a huge antitrust problem because he’s controlling so much; Amazon is controlling so much.”

In August, the president returned to the subject, taking aim at the company’s impact on bricks-and-mortar retailers. “Towns, cities and states throughout the US are being hurt — many jobs being lost!” he tweeted.

Still, most politicians regard Amazon as a potential economic boon. Some 238 communities answered the company’s request to identify sites for its planned second headquarters. It is not hard to see why: the $5bn project will directly create work for 50,000 people, plus “tens of thousands of additional jobs and tens of billions of dollars in additional investment in the surrounding community”, Amazon says.

Even critics of the company’s size, such as Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey, overcame their concerns. “Amazon would make the right business choice by coming here,” Mr Booker told a press conference last month in Newark.

Amazon, which declined to comment for this story, recognises its potential political problem. The company is on track to spend nearly $13m this year on lobbying the federal government compared with just $2.5m five years ago. In 2016 it added an antitrust lawyer, Seth Bloom, with experience on Capitol Hill and in the justice department.

Though the Trump administration approved the Whole Foods purchase, Amazon’s antitrust concerns have not evaporated. Congressman Keith Ellison, deputy chairman of the Democratic National Committee, who favours a break-up of all the digital players, says the online retailer should spin off its $12bn-a-year cloud computing business known as Amazon Web Services.

“I do think they should be forced to sell off huge parts,” he says. “They’re too big.”

The view is echoed by Mr Kristol, a prominent former official in the Reagan and George HW Bush administrations, who says the tech giants’ dominance hurts workers, consumers and the overall economy. His New Center project, aimed at overcoming political polarisation, supports tougher antitrust enforcement to address “monopolistic behaviour” in the technology sector.

Even among pro-market conservatives, sentiment is shifting on the need for greater government intervention. “People are at least open to the argument that concentration of power is a problem even if there’s no immediate cost paid by consumers,” Mr Kristol says.

US law does not prohibit monopolies so long as they arise through legitimate means. But companies are not permitted to exploit their dominance in one market to control another.

Competition authorities in the EU have moved more aggressively to corral the internet groups. Earlier this month the EU ordered Amazon to pay $290m in back taxes to Luxembourg after Margrethe Vestager, the EU competition chief, said the online retailer had benefited from special treatment.

Ms Vestager has also gone after American internet companies on antitrust grounds, levying a €2.4bn fine on Google in June and reaching a negotiated settlement with Amazon over its ebook distribution contracts. In May, Amazon agreed to scrap contract clauses requiring publishers to offer it terms that were as good or better than those offered to its competitors.

Amazon’s critics say that its role as an essential e-commerce platform for more than 2m other vendors and its control of data on their sales warrant government action. Last year, in a speech that ignited the Democrats’ renewed interest in anti-monopoly efforts, Ms Warren said companies like Amazon provide a platform “that lots of other companies depend on for survival”, adding, “the platform can become a tool to snuff out competition.” For its part, Amazon says it faces “intense competition”.

Critics remain unconvinced. Its control over a vast cache of customer data gives it “unprecedented . . . advantages in penetrating new industries and new markets”, according to Amir Konigsberg, chief executive and co-founder of Twiggle, which sells search and analytics software to Amazon competitors.

There’s no question that the company has grown through innovation and by meeting customer needs. But gobbling up rivals and would-be rivals has also been part of the equation. Since 2005, Amazon has acquired more than 60 companies including some that were at first reluctant to sell, such as Zappos, the online shoe retailer.

“It’s a dominant platform and a vertically integrated dominant platform,” says Lina Khan, author of an influential Yale Law Journal article earlier this year that ignited the debate. “It acts as a gatekeeper . . . It’s closing off the market to new entrants.”

Ms Khan says Amazon also has priced goods and services — such as its unlimited two-day Amazon Prime delivery service — below cost. By prioritising growth over profits, the company has unfairly squeezed competitors, she says.

Though Mr Cleland says antitrust enforcers could make a case against Amazon under the prevailing interpretation of US law, most analysts say a genuine push to break up or constrain the tech giants requires rethinking the antitrust orthodoxy of the past 40 years. The so-called Chicago School of antitrust theory, which focuses on consumer prices and innovation, is ill-equipped to cope with the internet world’s structural tendency to produce winner-takes-all outcomes.

“The rhetoric around consumer prices can disable antitrust law,” says Ms Khan. “These platforms present new issues.”

Wednesday, 30 August 2017

We need to nationalise Google, Facebook and Amazon. Here’s why

A crisis is looming. These monopoly platforms hoovering up our data have no competition: they’re too big to serve the public interest

Nick Srnicek in The Guardian

For the briefest moment in March 2014, Facebook’s dominance looked under threat. Ello, amid much hype, presented itself as the non-corporate alternative to Facebook. According to the manifesto accompanying its public launch, Ello would never sell your data to third parties, rely on advertising to fund its service, or require you to use your real name.

The hype fizzled out as Facebook continued to expand. Yet Ello’s rapid rise and fall is symptomatic of our contemporary digital world and the monopoly-style power accruing to the 21st century’s new “platform” companies, such as Facebook, Google and Amazon. Their business model lets them siphon off revenues and data at an incredible pace, and consolidate themselves as the new masters of the economy. Monday brought another giant leap as Amazon raised the prospect of an international grocery price war by slashing prices on its first day in charge of the organic retailer Whole Foods.

The platform – an infrastructure that connects two or more groups and enables them to interact – is crucial to these companies’ power. None of them focuses on making things in the way that traditional companies once did. Instead, Facebook connects users, advertisers, and developers; Uber, riders and drivers; Amazon, buyers and sellers.

Reaching a critical mass of users is what makes these businesses successful: the more users, the more useful to users – and the more entrenched – they become. Ello’s rapid downfall occurred because it never reached the critical mass of users required to prompt an exodus from Facebook – whose dominance means that even if you’re frustrated by its advertising and tracking of your data, it’s still likely to be your first choice because that’s where everyone is, and that’s the point of a social network. Likewise with Uber: it makes sense for riders and drivers to use the app that connects them with the biggest number of people, regardless of the sexism of Travis Kalanick, the former chief executive, or the ugly ways in which it controls drivers, or the failures of the company to report serious sexual assaults by its drivers.

Network effects generate momentum that not only helps these platforms survive controversy, but makes it incredibly difficult for insurgents to replace them.

As a result, we have witnessed the rise of increasingly formidable platform monopolies. Google, Facebook and Amazon are the most important in the west. (China has its own tech ecosystem.) Google controls search, Facebook rules social media, and Amazon leads in e-commerce. And they are now exerting their power over non-platform companies – a tension likely to be exacerbated in the coming decades. Look at the state of journalism: Google and Facebook rake in record ad revenues through sophisticated algorithms; newspapers and magazines see advertisers flee, mass layoffs, the shuttering of expensive investigative journalism, and the collapse of major print titles like the Independent. A similar phenomenon is happening in retail, with Amazon’s dominance undermining old department stores.

These companies’ power over our reliance on data adds a further twist. Data is quickly becoming the 21st-century version of oil – a resource essential to the entire global economy, and the focus of intense struggle to control it. Platforms, as spaces in which two or more groups interact, provide what is in effect an oil rig for data. Every interaction on a platform becomes another data point that can be captured and fed into an algorithm. In this sense, platforms are the only business model built for a data-centric economy.

More and more companies are coming to realise this. We often think of platforms as a tech-sector phenomenon, but the truth is that they are becoming ubiquitous across the economy. Uber is the most prominent example, turning the staid business of taxis into a trendy platform business. Siemens and GE, two powerhouses of the 20th century, are fighting it out to develop a cloud-based system for manufacturing. Monsanto and John Deere, two established agricultural companies, are trying to figure out how to incorporate platforms into farming and food production.

And this poses problems. At the heart of platform capitalism is a drive to extract more data in order to survive. One way is to get people to stay on your platform longer. Facebook is a master at using all sorts of behavioural techniques to foster addictions to its service: how many of us scroll absentmindedly through Facebook, barely aware of it?

Another way is to expand the apparatus of extraction. This helps to explain why Google, ostensibly a search engine company, is moving into the consumer internet of things (Home/Nest), self-driving cars (Waymo), virtual reality (Daydream/Cardboard), and all sorts of other personal services. Each of these is another rich source of data for the company, and another point of leverage over their competitors.

Others have simply bought up smaller companies: Facebook has swallowed Instagram ($1bn), WhatsApp ($19bn), and Oculus ($2bn), while investing in drone-based internet, e-commerce and payment services. It has even developed a tool that warns when a start-up is becoming popular and a possible threat. Google itself is among the most prolific acquirers of new companies, at some stages purchasing a new venture every week. The picture that emerges is of increasingly sprawling empires designed to vacuum up as much data as possible.

But here we get to the real endgame: artificial intelligence (or, less glamorously, machine learning). Some enjoy speculating about wild futures involving a Terminator-style Skynet, but the more realistic challenges of AI are far closer. In the past few years, every major platform company has turned its focus to investing in this field. As the head of corporate development at Google recently said, “We’re definitely AI first.”

Tinkering with minor regulations while AI companies amass power won’t do

All the dynamics of platforms are amplified once AI enters the equation: the insatiable appetite for data, and the winner-takes-all momentum of network effects. And there is a virtuous cycle here: more data means better machine learning, which means better services and more users, which means more data. Currently Google is using AI to improve its targeted advertising, and Amazon is using AI to improve its highly profitable cloud computing business. As one AI company takes a significant lead over competitors, these dynamics are likely to propel it to an increasingly powerful position.

What’s the answer? We’ve only begun to grasp the problem, but in the past, natural monopolies like utilities and railways that enjoy huge economies of scale and serve the common good have been prime candidates for public ownership. The solution to our newfangled monopoly problem lies in this sort of age-old fix, updated for our digital age. It would mean taking back control over the internet and our digital infrastructure, instead of allowing them to be run in the pursuit of profit and power. Tinkering with minor regulations while AI firms amass power won’t do. If we don’t take over today’s platform monopolies, we risk letting them own and control the basic infrastructure of 21st-century society.

Nick Srnicek in The Guardian

For the briefest moment in March 2014, Facebook’s dominance looked under threat. Ello, amid much hype, presented itself as the non-corporate alternative to Facebook. According to the manifesto accompanying its public launch, Ello would never sell your data to third parties, rely on advertising to fund its service, or require you to use your real name.

The hype fizzled out as Facebook continued to expand. Yet Ello’s rapid rise and fall is symptomatic of our contemporary digital world and the monopoly-style power accruing to the 21st century’s new “platform” companies, such as Facebook, Google and Amazon. Their business model lets them siphon off revenues and data at an incredible pace, and consolidate themselves as the new masters of the economy. Monday brought another giant leap as Amazon raised the prospect of an international grocery price war by slashing prices on its first day in charge of the organic retailer Whole Foods.

The platform – an infrastructure that connects two or more groups and enables them to interact – is crucial to these companies’ power. None of them focuses on making things in the way that traditional companies once did. Instead, Facebook connects users, advertisers, and developers; Uber, riders and drivers; Amazon, buyers and sellers.

Reaching a critical mass of users is what makes these businesses successful: the more users, the more useful to users – and the more entrenched – they become. Ello’s rapid downfall occurred because it never reached the critical mass of users required to prompt an exodus from Facebook – whose dominance means that even if you’re frustrated by its advertising and tracking of your data, it’s still likely to be your first choice because that’s where everyone is, and that’s the point of a social network. Likewise with Uber: it makes sense for riders and drivers to use the app that connects them with the biggest number of people, regardless of the sexism of Travis Kalanick, the former chief executive, or the ugly ways in which it controls drivers, or the failures of the company to report serious sexual assaults by its drivers.

Network effects generate momentum that not only helps these platforms survive controversy, but makes it incredibly difficult for insurgents to replace them.

As a result, we have witnessed the rise of increasingly formidable platform monopolies. Google, Facebook and Amazon are the most important in the west. (China has its own tech ecosystem.) Google controls search, Facebook rules social media, and Amazon leads in e-commerce. And they are now exerting their power over non-platform companies – a tension likely to be exacerbated in the coming decades. Look at the state of journalism: Google and Facebook rake in record ad revenues through sophisticated algorithms; newspapers and magazines see advertisers flee, mass layoffs, the shuttering of expensive investigative journalism, and the collapse of major print titles like the Independent. A similar phenomenon is happening in retail, with Amazon’s dominance undermining old department stores.

These companies’ power over our reliance on data adds a further twist. Data is quickly becoming the 21st-century version of oil – a resource essential to the entire global economy, and the focus of intense struggle to control it. Platforms, as spaces in which two or more groups interact, provide what is in effect an oil rig for data. Every interaction on a platform becomes another data point that can be captured and fed into an algorithm. In this sense, platforms are the only business model built for a data-centric economy.

More and more companies are coming to realise this. We often think of platforms as a tech-sector phenomenon, but the truth is that they are becoming ubiquitous across the economy. Uber is the most prominent example, turning the staid business of taxis into a trendy platform business. Siemens and GE, two powerhouses of the 20th century, are fighting it out to develop a cloud-based system for manufacturing. Monsanto and John Deere, two established agricultural companies, are trying to figure out how to incorporate platforms into farming and food production.

And this poses problems. At the heart of platform capitalism is a drive to extract more data in order to survive. One way is to get people to stay on your platform longer. Facebook is a master at using all sorts of behavioural techniques to foster addictions to its service: how many of us scroll absentmindedly through Facebook, barely aware of it?

Another way is to expand the apparatus of extraction. This helps to explain why Google, ostensibly a search engine company, is moving into the consumer internet of things (Home/Nest), self-driving cars (Waymo), virtual reality (Daydream/Cardboard), and all sorts of other personal services. Each of these is another rich source of data for the company, and another point of leverage over their competitors.

Others have simply bought up smaller companies: Facebook has swallowed Instagram ($1bn), WhatsApp ($19bn), and Oculus ($2bn), while investing in drone-based internet, e-commerce and payment services. It has even developed a tool that warns when a start-up is becoming popular and a possible threat. Google itself is among the most prolific acquirers of new companies, at some stages purchasing a new venture every week. The picture that emerges is of increasingly sprawling empires designed to vacuum up as much data as possible.

But here we get to the real endgame: artificial intelligence (or, less glamorously, machine learning). Some enjoy speculating about wild futures involving a Terminator-style Skynet, but the more realistic challenges of AI are far closer. In the past few years, every major platform company has turned its focus to investing in this field. As the head of corporate development at Google recently said, “We’re definitely AI first.”

Tinkering with minor regulations while AI companies amass power won’t do

All the dynamics of platforms are amplified once AI enters the equation: the insatiable appetite for data, and the winner-takes-all momentum of network effects. And there is a virtuous cycle here: more data means better machine learning, which means better services and more users, which means more data. Currently Google is using AI to improve its targeted advertising, and Amazon is using AI to improve its highly profitable cloud computing business. As one AI company takes a significant lead over competitors, these dynamics are likely to propel it to an increasingly powerful position.

What’s the answer? We’ve only begun to grasp the problem, but in the past, natural monopolies like utilities and railways that enjoy huge economies of scale and serve the common good have been prime candidates for public ownership. The solution to our newfangled monopoly problem lies in this sort of age-old fix, updated for our digital age. It would mean taking back control over the internet and our digital infrastructure, instead of allowing them to be run in the pursuit of profit and power. Tinkering with minor regulations while AI firms amass power won’t do. If we don’t take over today’s platform monopolies, we risk letting them own and control the basic infrastructure of 21st-century society.

Thursday, 24 August 2017