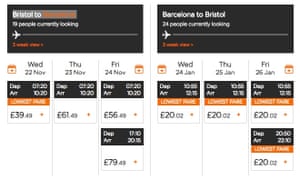

You wait 24 hours to book that flight, only to find it’s gone up by £100. You wait until Black Friday to buy that leather jacket and, sure enough, it’s been marked down. Today’s consumers are getting comfortable with the idea that prices online can fluctuate, not just at sale time, but several times over the course of a single day. Anyone who has booked a holiday on the internet is familiar with the concept, if not with its name. It’s known as dynamic pricing: when the cost of goods or services ebbs and flows in response to the slightest shifts in supply and demand, be it fresh croissants in the morning, a bargain TV or an Uber during a late-night “surge”.

Sports teams, entertainment venues and theme parks have started to use dynamic pricing methods, too, taking their cues from airlines and hotels to calibrate a range of ticketing deals that ensure they fill as many seats as possible. Last month, Regal, the US cinema chain, announced it would trial a form of dynamic ticket pricing at many of its multiplexes in 2018, in the hope of boosting its box office revenue. Digonex, one of the leading dynamic ticketing firms in the US, has consulted for Derby County and Manchester City football clubs in the UK. “In five years, dynamic pricing will be common practice in the attractions space,” says the company’s CEO, Greg Loewen. “The same goes for many other industries: movies, parking, tour operators.” Amazon, the world’s largest online retailer, tweaks countless prices every day. Savvy shoppers have learned to wait for bargains with the help of other sites such as CamelCamelCamel.com, which analyses Amazon price drops and lists the biggest. On a single day on Amazon.co.uk last week, those included a Samsung Galaxy S7 phone, down 14% from £510.29 to £439, and a pack of six 300g jars of Ovaltine, down 33% from £17.94 to £12.

Physical retailers can’t match the agility of their online rivals, not least because changing prices requires altering labels. But “smart shelves” – already common in European supermarkets – are coming to the UK, with digital price displays that allow retailers to offer deals at different times of day, along with information about the products. Sainsbury’s, Morrisons and Tesco have all trialled electronic pricing systems in select stores. Marks & Spencer conducted an electronic pricing experiment last year, selling sandwiches more cheaply during the morning rush hour to encourage commuters to buy their lunch early.

Toby Pickard, senior innovations and trends analyst at the grocery research firm IGD, says this new technology will benefit retailers by enabling them “to gain more data about the products they sell; for example, they can closely gauge how prices fluctuating throughout the day may alter shoppers’ purchasing habits, or if on-shelf digital product reviews increase sales.” IGD’s research suggests there is an appetite for this sort of tech from consumers, too. For example, says Pickard: “Four in 10 shoppers say they are interested in being alerted to offers on their phone while in-store.”

FacebookTwitterPinterest M&S experimented with pricing to encourage commuters to buy their lunch early. Photograph: Luke Johnson/Commissioned for The Guardian

Earlier this year, the Luxembourg-based computer firm SES took a majority stake in the Irish software firm MarketHub. Together, they are bringing data analysis and smart-shelf-style systems to some 14,000 stores in 54 countries including the UK. MarketHub says two Spar stores in London have succeeded in raising revenue and decreasing waste since introducing its technology. For the firm’s CEO Roy Horgan, though, there’s a big difference between what MarketHub offers and dynamic pricing per se. “I don’t see dynamic pricing happening in major retailers,” he says. “Supermarkets have huge, complicated logistics systems. They can’t react in real time to what’s going in their stores the way Amazon can. [Physical retailers] want to discount, to have more relevant deals, fewer promotions, better value and more customer loyalty. That’s not about changing the price of individual products, it’s more about changing deals.”

As examples, Horgan suggests offering cheap lunch deals in the morning (à la M&S), so that workers don’t have to queue up at lunchtime, or guiding shoppers with limited budgets to discounted ingredients for an evening meal. “That’s not dynamic pricing,” he says. “It’s just agile retail.”

A recent survey of US consumers by Retail Systems Research (RSR) found that 71% didn’t care for the idea of dynamic pricing, though millennials were more amenable to the concept, with 14% of younger shoppers saying they “loved” it. Perhaps that ought not to be surprising, given the younger generation’s greater familiarity with browsing for bargains online.

“Consumers always love it when they can get a great deal, and dynamic pricing isn’t just about raising prices – it often leads to lowering them,” says Loewen. “In general, we have found that when prices are transparent to consumers and they understand the ‘rules of the game’, they adapt to dynamic pricing fairly seamlessly and even embrace it.”

Simon Read, a money and personal finance writer, says: “If you’re desperate for an item and it’s the last available, you are likely to pay a premium when dynamic pricing comes into play.” But dynamic pricing can also play to the consumer’s benefit, he explains.

“The truth is that retailers want to flog their wares at whatever price they can get. If you want to take advantage of dynamic pricing, you’ll need to find out when retailers are desperate to sell. In bricks-and-mortar stores that means shopping at quiet times – in the morning – or waiting until closing time when grocers need to clear their shelves.” If you’re shopping online, Read says, research the normal price of an item before buying it, so as not to be caught out. “It’s also a good idea to leave things in your shopping basket at most online retailers rather than buying immediately. After a day or two, you will often get an email offering a decent reduction.”

Those consumers who are suspicious of dynamic pricing may also be confusing it with (the far more controversial) personalised pricing, whereby specific customers are asked to pay different amounts for the same product, tailored to what the retailer thinks they can and will spend – using personal data points that might one day include, for instance, our credit rating. In 2014, the US Department of Transportation approved a system allowing airlines and travel companies to collect passengers’ data to present them with “personalised offerings” based on their address, their marital status, their birthday and their travel history. It’s not hard to imagine that the fares you are offered might be higher than for others if, say, you live in an affluent postcode and your husband’s birthday is coming up.

Airlines use dynamic pricing on flight tickets. Photograph: Easyjet

In 2012, the travel site Orbitz was found to be adjusting its prices for users of Apple Mac computers, after finding that they were prepared to spend up to 30% more on hotel rooms than other customers. That same year, the Wall Street Journal revealed that the Staples website offered products at different pricesdepending on the user’s proximity to rival stores. In 2014, a study conducted by Northeastern University in Boston found that several major e-commerce sites such as Home Depot and Walmart were manipulating prices based on the browsing history of individual customers. “Most people assume the internet is a neutral environment like the high street, where the price you see is the same as the one everyone else sees,” says Ariel Ezrachi, director of the University of Oxford Centre for Competition Law and Policy. “But on the high street you’re anonymous; online, the seller has information about you, and about your other buying options.”

Dynamic pricing, says Ezrachi, is simply a way for businesses to respond nimbly to market trends, and thus is within the bounds of what consumers already accept as market dynamics. “Personalised pricing is much more problematic. It’s based on asymmetricity of information; it’s only possible because the shopper doesn’t know what information the seller has about them, and because the seller is able to create an environment where the shopper believes they are seeing the market price.”

The ethics of pricing based on an individual’s personal data are vexed: some consumers will find it manipulative and insist on its regulation; others may feel it’s fair – socially beneficial, even – to charge wealthy customers more for a product or service. “You will find people arguing in different directions,” Ezrachi says. Loyalty cards have long enabled supermarkets and other major retailers to offer personalised offers based on the spending habits of repeat customers. B&Q has tested electronic price tags that display different prices to different customers using information gleaned from their phones (the company made clear that their intention was to “reward regular customers with discounts”, not to raise the price for more profligate shoppers). In the US, Coca-Cola and Albertsons supermarkets have experimented with targeting shoppers in-store by sending personalised offers to their phones when they approach the soft drinks aisle in an Albertsons store.

Horgan resists the idea that supermarkets will embrace personalised pricing. “In the airline industry, we have more freedom, information and choice on airlines than we’ve ever had before, and that is all dynamic-pricing led. But nobody’s loyal to Ryanair; they’re loyal to the deal. Retail is different,” he says. “If I have five pounds in my pocket and a family of four to feed, I want to know I can generate a recipe that is nutritious for them, and I want an app that can navigate me around the store to find a deal on [the necessary ingredients]. To me, that is personalised retail. But any [bricks and mortar] retailer who charges different prices to different people for the same product is an idiot. They’re only going to lose loyalty.”

Loewen agrees that personalised pricing carries as many dangers as opportunities for retailers. “Consumers are more empowered and informed than ever before, and any pricing strategy that seeks to fool or mislead them is unlikely to be successful for long,” he says. Nevertheless, in the dawning era of dynamic pricing, personalised pricing and agile retailing, the days of fixed prices seem to be coming to an end. And although the technology may be more advanced, in some ways dynamic pricing is simply a return to the days long before supermarkets, when traders would judge how high or low a price to haggle from a customer based on factors as simple as the sound of their accent, or the cut of their cloak.

No comments:

Post a Comment