Sex scandals, rows over terrorism, fears for its impact on social policy: the backlash against Big Tech has begun. Where will it end?

Evgeny Morozov in The Guardian

Just a decade ago, Silicon Valley pitched itself as a savvy ambassador of a newer, cooler, more humane kind of capitalism. It quickly became the darling of the elite, of the international media, and of that mythical, omniscient tribe: the “digital natives”. While an occasional critic – always easy to dismiss as a neo-Luddite – did voice concerns about their disregard for privacy or their geeky, almost autistic aloofness, public opinion was firmly on the side of technology firms.

Silicon Valley was the best that America had to offer; tech companies frequently occupied – and still do – top spots on lists of the world’s most admired brands. And there was much to admire: a highly dynamic, innovative industry, Silicon Valley has found a way to convert scrolls, likes and clicks into lofty political ideals, helping to export freedom, democracy and human rights to the Middle East and north Africa. Who knew that the only thing thwarting the global democratic revolution was capitalism’s inability to capture and monetise the eyeballs of strangers?

How things have changed. An industry once hailed for fuelling the Arab spring is today repeatedly accused of abetting Islamic State. An industry that prides itself on diversity and tolerance is now regularly in the news for cases of sexual harassment as well as the controversial views of its employees on matters such as gender equality. An industry that built its reputation on offering us free things and services is now regularly assailed for making other things – housing, above all– more expensive.

The Silicon Valley backlash is on. These days, one can hardly open a major newspaper – including such communist rags as the Financial Times and the Economist – without stumbling on passionate calls that demand curbs on the power of what is now frequently called “Big Tech”, from reclassifying digital platforms as utility companies to even nationalising them.

Meanwhile, Silicon Valley’s big secret – that the data produced by users of digital platforms often has economic value exceeding the value of the services rendered – is now also out in the open. Free social networking sounds like a good idea – but do you really want to surrender your privacy so that Mark Zuckerberg can run a foundation to rid the world of the problems that his company helps to perpetuate? Not everyone is so sure any longer. The Teflon industry is Teflon no more: the dirt thrown at it finally sticks – and this fact is lost on nobody.

Much of the brouhaha has caught Silicon Valley by surprise. Its ideas – disruption as a service, radical transparency as a way of being, an entire economy of gigs and shares – still dominate our culture. However, its global intellectual hegemony is built on shaky foundations: it stands on the post-political can-do allure of TED talks much more than in wonky thinktank reports and lobbying memorandums.

This is not to say that technology firms do not dabble in lobbying – here Alphabet is on a par with Goldman Sachs – nor to imply that they don’t steer academic research. In fact, on many tech policy issues it’s now difficult to find unbiased academics who have not received some Big Tech funding. Those who go against the grain find themselves in a rather precarious situation, as was recently shown by the fate of the Open Markets project at New America, an influential thinktank in Washington: its strong anti-monopoly stance appears to have angered New America’s chairman and major donor, Eric Schmidt, executive chairman of Alphabet. As a result, it was spun off from the thinktank.

Nonetheless, Big Tech’s political influence is not at the level of Wall Street or Big Oil. It’s hard to argue that Alphabet wields as much power over global technology policy as the likes of Goldman Sachs do over global financial and economic policy. For now, influential politicians – such as José Manuel Barroso, the former president of the European Commission – prefer to continue their careers at Goldman Sachs, not at Alphabet; it is also the former, not the latter, that fills vacant senior posts in Washington.

This will surely change. It’s obvious that the cheerful and utopian chatterboxes who make up TED talks no longer contribute much to boosting the legitimacy of the tech sector; fortunately, there’s a finite supply of bullshit on this planet. Big digital platforms will thus seek to acquire more policy leverage, following the playbook honed by the tobacco, oil and financial firms.

There are, however, two additional factors worth considering in order to understand where the current backlash against Big Tech might lead. First of all, short of a major privacy disaster, digital platforms will continue to be the world’s most admired and trusted brands – not least because they contrast so favourably with your average telecoms company or your average airline (say what you will of their rapaciousness, but tech firms don’t generally drag their customers off their flights).

And it is technology firms – American companies but also Chinese – that create the false impression that the global economy has recovered and everything is back to normal. Since January, the valuations of just four firms – Alphabet, Amazon, Facebook and Microsoft – have grown by an amount greater than the entire GDP of oil-rich Norway. Who would want to see this bubble burst? Nobody; in fact, those in power would rather see it grow some more.

The culture power of Silicon Valley can be gleaned from the simple fact that no sensible politician dares to go to Wall Street for photo ops; everyone goes to Palo Alto to unveil their latest pro-innovation policy. Emmanuel Macron wants to turn France into a startup, not a hedge fund. There’s no other narrative in town that makes centrist, neoliberal policies look palatable and inevitable at the same time; politicians, however angry they might sound about Silicon Valley’s monopoly power, do not really have an alternative project. It’s not just Macron: from Italy’s Matteo Renzi to Canada’s Justin Trudeau, all mainstream politicians who have claimed to offer a clever break with the past also offer an implicit pact with Big Tech – or, at least, its ideas – in the future.

Second, Silicon Valley, being the home of venture capital, is good at spotting global trends early on. Its cleverest minds had sensed the backlash brewing before the rest of us. They also made the right call in deciding that wonky memos and thinktank reports won’t quell our discontent, and that many other problems – from growing inequality to the general unease about globalisation – will eventually be blamed on an industry that did little to cause them.

Silicon Valley’s brightest minds realised they needed bold proposals – a guaranteed basic income, a tax on robots, experiments with fully privatised cities to be run by technology companies outside of government jurisdiction – that will sow doubt in the minds of those who might have otherwise opted for conventional anti-monopoly legislation. If technology firms can play a constructive role in funding our basic income, if Alphabet or Amazon can run Detroit or New York with the same efficiency that they run their platforms, if Microsoft can infer signs of cancer from our search queries: should we really be putting obstacles in their way?

In the boldness and vagueness of its plans to save capitalism, Silicon Valley might out-TED the TED talks. There are many reasons why such attempts won’t succeed in their grand mission even if they would make these firms a lot of money in the short term and help delay public anger by another decade. The main reason is simple: how could one possibly expect a bunch of rent-extracting enterprises with business models that are reminiscent of feudalism to resuscitate global capitalism and to establish a new New Deal that would constrain the greed of capitalists, many of whom also happen to be the investors behind these firms?

Data might seem infinite but there’s no reason to believe that the enormous profits made from it would simply smooth over the many contradictions of the current economic system. A self-proclaimed caretaker of global capitalism, Silicon Valley is much more likely to end up as its undertaker.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label thinktank. Show all posts

Showing posts with label thinktank. Show all posts

Sunday, 3 September 2017

Saturday, 30 November 2013

Heard a thinktank on the BBC? You haven't heard the whole story

When the BBC interviews someone about smoking, it's supposed to reveal if the thinktank they work for receives funding from tobacco companies

Mark Littlewood of the IEA spoke about cigarette packaging on Radio 4 this week. Not mentioned was that the institute receives funding from tobacco companies. Photograph: Alex Sturrock

Do the BBC's editorial guidelines count for anything? I ask because it disregards them every day, by failing to reveal the commercial interests of its contributors.

Let me give you an example. On Thursday the Today programme covered the plain packaging of cigarettes. It interviewed Mark Littlewood, director-general of the Institute of Economic Affairs, an organisation that calls itself a thinktank. Mishal Husain introduced Mark Littlewood as "the director of the Institute of Economic Affairs, and a smoker himself".

Fine. But should we not also have been informed that the Institute of Economic Affairs receives funding from tobacco companies? It's bad enough when the BBC interviews people about issues of great financial importance to certain corporations when it has no idea whether or not these people are funded by those corporations – and makes no effort to find out. It's even worse when those interests have already been exposed, yet the BBC still fails to mention them.

Both the Institute of Economic Affairs and the Adam Smith Institute have been funded by tobacco firms for years. The former has been funded by British American Tobacco since 1963, and has also been paid by Philip Morris and Japan Tobacco International. It has never come clean about this funding, and still refuses to say which other corporations sponsor it.

Yet, as you can see from its lists, the institute's spokespeople appear all over the media, arguing against any regulations tobacco companies don't like, without ever being obliged to reveal that tobacco companies help pay their wages.

Most of the so-called thinktanks flatly refuse to reveal their interests. I see the IEA, the Adam Smith Institute and other "thinktanks" which refuse to to say who funds them asindistinguishable from corporate lobbyists. I see them as doing the dirty work of corporations which won't put their own heads above the parapet because of the likely reputational damage.

I'm not the only one who sees them in this light. David Frum was formerly a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a rightwing pro-business thinktank. Drawing on his own experience, he explained that such groups "increasingly function as public-relations agencies".

The veteran corporate lobbyist Jeff Judson explained why thinktanks are so useful to corporations: "Lobbyists often work for specific clients who operate at the mercy of a regulator or lawmaker, making them vulnerable to retribution for daring to criticise or speak out. Thinktanks are virtually immune to retribution … Donors are confidential. The identity of donors to thinktanks is protected from involuntary disclosure."(Judson's confessions used to be available here. They have since been removed.)

Here's what Mark Littlewood said on the Today programme: "The evidence out of Australia, who, in their extreme unwisdom in my view, have offered to be the guinea pigs for planet earth on whether this policy works, having had plain packaging or standardised packaging in place for a year over there, the early evidence suggests no change at all on smoking prevalence. And, lo and behold, the black market in cigarettes has jumped markedly."

Mishal Husain then remarked, "Well that's one view, in a moment we'll hear that of the public health minister ..."

Yes, it is one view. The view of someone being paid by big tobacco. Should we not have known that?

Here's what the BBC's editorial guidelines say about such matters:

3.4.7: "We should make checks to establish the credentials of our contributors and to avoid being 'hoaxed'."

3.4.12: "We should normally identify on-air and online sources of information and significant contributors, and provide their credentials, so that our audiences can judge their status."

4.4.14: "We should not automatically assume that contributors from other organisations (such as academics, journalists, researchers and representatives of charities) are unbiased, and we may need to make it clear to the audience when contributors are associated with a particular viewpoint, if it is not apparent from their contribution or from the context in which their contribution is made."

3.4.7: "We should make checks to establish the credentials of our contributors and to avoid being 'hoaxed'."

3.4.12: "We should normally identify on-air and online sources of information and significant contributors, and provide their credentials, so that our audiences can judge their status."

4.4.14: "We should not automatically assume that contributors from other organisations (such as academics, journalists, researchers and representatives of charities) are unbiased, and we may need to make it clear to the audience when contributors are associated with a particular viewpoint, if it is not apparent from their contribution or from the context in which their contribution is made."

Every day people from thinktanks are interviewed by the BBC's news and current affairs programmes without any such safeguards being applied. There is no effort to establish their credentials, in order to avoid being hoaxed into promoting corporate lobbyists as independent thinkers. There is no effort to identify on whose behalf they are speaking, "so that our audiences can judge their status." There is no attempt to make it clear to the audience that contributors are funded by the companies whose products they are discussing.

I would have no problem with the BBC interviewing people from these thinktanks if their interests were disclosed. If these organisations refuse to say who funds them, they should not be allowed on air. Their financial interests in the issue under discussion should be mentioned by the presenter when they are introduced.

I've been banging on about this for years, with no result at all. It seems that the only thing the BBC responds to is formal complaints. So please complain.

Here are three things you can do:

• Use the corporation's online complaints form

• Take the issue to the BBC Trust

• Complain to Feedback on Radio 4

• Use the corporation's online complaints form

• Take the issue to the BBC Trust

• Complain to Feedback on Radio 4

Otherwise, expect our bastion of editorial values to keep collaborating in the time-honoured tradition of hoaxing us on behalf of corporate money.

Friday, 15 February 2013

Secret funding helped build vast network of climate denial thinktanks

Anonymous billionaires donated $120m to more than 100 anti-climate groups working to discredit climate change science

• How Donors Trust distributed millions to anti-climate groups

• How Donors Trust distributed millions to anti-climate groups

- Suzanne Goldenberg, US environment correspondent

- guardian.co.uk,

Climate sceptic groups are mobilising against Obama’s efforts to act on climate change in his second term. Photograph: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Conservative billionaires used a secretive funding route to channel nearly $120m (£77m) to more than 100 groups casting doubt about the science behind climate change, the Guardian has learned.

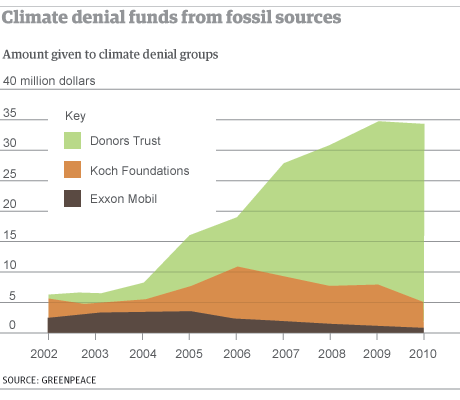

The funds, doled out between 2002 and 2010, helped build a vast network of thinktanks and activist groups working to a single purpose: to redefine climate change from neutral scientific fact to a highly polarising "wedge issue" for hardcore conservatives.

The millions were routed through two trusts, Donors Trust and the Donors Capital Fund, operating out of a generic town house in the northern Virginia suburbs of Washington DC. Donors Capital caters to those making donations of $1m or more.

Whitney Ball, chief executive of the Donors Trust told the Guardian that her organisation assured wealthy donors that their funds would never by diverted to liberal causes.

The funding stream far outstripped the support from more visible opponents of climate action such as the oil industry or the conservative billionaire Koch brothers. Photograph: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

The funding stream far outstripped the support from more visible opponents of climate action such as the oil industry or the conservative billionaire Koch brothers. Photograph: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

"We exist to help donors promote liberty which we understand to be limited government, personal responsibility, and free enterprise," she said in an interview.

By definition that means none of the money is going to end up with groups like Greenpeace, she said. "It won't be going to liberals."

Ball won't divulge names, but she said the stable of donors represents a wide range of opinion on the American right. Increasingly over the years, those conservative donors have been pushing funds towards organisations working to discredit climate science or block climate action.

Donors exhibit sharp differences of opinion on many issues, Ball said. They run the spectrum of conservative opinion, from social conservatives to libertarians. But in opposing mandatory cuts to greenhouse gas emissions, they found common ground.

"Are there both sides of an environmental issue? Probably not," she went on. "Here is the thing. If you look at libertarians, you tend to have a lot of differences on things like defence, immigration, drugs, the war, things like that compared to conservatives. When it comes to issues like the environment, if there are differences, they are not nearly as pronounced."

By 2010, the dark money amounted to $118m distributed to 102 thinktanks or action groups which have a record of denying the existence of a human factor in climate change, or opposing environmental regulations.

The money flowed to Washington thinktanks embedded in Republican party politics, obscure policy forums in Alaska and Tennessee, contrarian scientists at Harvard and lesser institutions, even to buy up DVDs of a film attacking Al Gore.

The ready stream of cash set off a conservative backlash against Barack Obama's environmental agenda that wrecked any chance of Congress taking action on climate change.

Graphic: climate denial funding

Graphic: climate denial funding

Those same groups are now mobilising against Obama's efforts to act on climate change in his second term. A top recipient of the secret funds on Wednesday put out a point-by-point critique of the climate content in the president's state of the union address.

And it was all done with a guarantee of complete anonymity for the donors who wished to remain hidden.

"The funding of the denial machine is becoming increasingly invisible to public scrutiny. It's also growing. Budgets for all these different groups are growing," said Kert Davies, research director of Greenpeace, which compiled the data on funding of the anti-climate groups using tax records.

"These groups are increasingly getting money from sources that are anonymous or untraceable. There is no transparency, no accountability for the money. There is no way to tell who is funding them," Davies said.

The trusts were established for the express purpose of managing donations to a host of conservative causes.

Such vehicles, called donor-advised funds, are not uncommon in America. They offer a number of advantages to wealthy donors. They are convenient, cheaper to run than a private foundation, offer tax breaks and are lawful.

That opposition hardened over the years, especially from the mid-2000s where the Greenpeace record shows a sharp spike in funds to the anti-climate cause.

In effect, the Donors Trust was bankrolling a movement, said Robert Brulle, a Drexel University sociologist who has extensively researched the networks of ultra-conservative donors.

"This is what I call the counter-movement, a large-scale effort that is an organised effort and that is part and parcel of the conservative movement in the United States " Brulle said. "We don't know where a lot of the money is coming from, but we do know that Donors Trust is just one example of the dark money flowing into this effort."

In his view, Brulle said: "Donors Trust is just the tip of a very big iceberg."

The rise of that movement is evident in the funding stream. In 2002, the two trusts raised less than $900,000 for the anti-climate cause. That was a fraction of what Exxon Mobil or the conservative oil billionaire Koch brothers donated to climate sceptic groups that year.

By 2010, the two Donor Trusts between them were channelling just under $30m to a host of conservative organisations opposing climate action or science. That accounted to 46% of all their grants to conservative causes, according to the Greenpeace analysis.

The funding stream far outstripped the support from more visible opponents of climate action such as the oil industry or the conservative billionaire Koch brothers, the records show. When it came to blocking action on the climate crisis, the obscure charity in the suburbs was outspending the Koch brothers by a factor of six to one.

"There is plenty of money coming from elsewhere," said John Mashey, a retired computer executive who has researched funding for climate contrarians. "Focusing on the Kochs gets things confused. You can not ignore the Kochs. They have their fingers in too many things, but they are not the only ones."

It is also possible the Kochs continued to fund their favourite projects using the anonymity offered by Donor Trust.

But the records suggest many other wealthy conservatives opened up their wallets to the anti-climate cause – an impression Ball wishes to stick.

She argued the media had overblown the Kochs support for conservative causes like climate contrarianism over the years. "It's so funny that on the right we think George Soros funds everything, and on the left you guys think it is the evil Koch brothers who are behind everything. It's just not true. If the Koch brothers didn't exist we would still have a very healthy organisation," Ball said.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)