Amol Rajan in BBC

In a briefing and accompanying editorial earlier this summer, that distinguished newspaper (it's a magazine, but still calls itself a newspaper, and I'm happy to indulge such eccentricity) argued that data is today what oil was a century ago.

As The Economist put it, "A new commodity spawns a lucrative, fast-growing industry, prompting anti-trust regulators to step in to restrain those who control its flow." Never mind that data isn't particularly new (though the volume may be) - this argument does, at first glance, have much to recommend it.

Just as a century ago those who got to the oil in the ground were able to amass vast wealth, establish near monopolies, and build the future economy on their own precious resource, so data companies like Facebook and Google are able to do similar now. With oil in the 20th century, a consensus eventually grew that it would be up to regulators to intervene and break up the oligopolies - or oiliogopolies - that threatened an excessive concentration of power.

Many impressive thinkers have detected similarities between data today and oil in yesteryear. John Thornhill, the Financial Times's Innovation Editor, has used the example of Alaska to argue that data companies should pay a universal basic income, another idea that has become highly fashionable in policy circles.

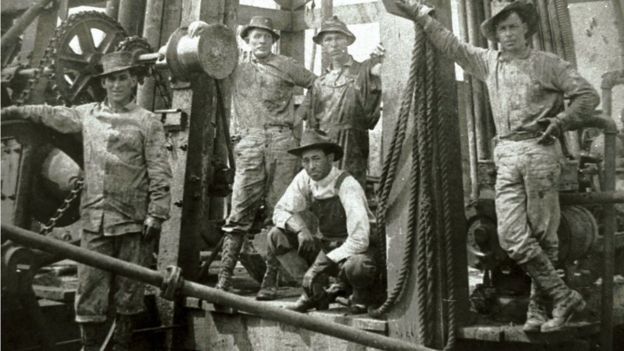

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESImage caption A drilling crew poses for a photograph at Spindletop Hill in Beaumont, Texas where the first Texas oil gusher was discovered in 1901.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESImage caption A drilling crew poses for a photograph at Spindletop Hill in Beaumont, Texas where the first Texas oil gusher was discovered in 1901.At first I was taken by the parallels between data and oil. But now I'm not so sure. As I argued in a series of tweets last week, there are such important differences between data today and oil a century ago that the comparison, while catchy, risks spreading a misunderstanding of how these new technology super-firms operate - and what to do about their power.

The first big difference is one of supply. There is a finite amount of oil in the ground, albeit that is still plenty, and we probably haven't found all of it. But data is virtually infinite. Its supply is super-abundant. In terms of basic supply, data is more like sunlight than oil: there is so much of it that our principal concern should be more what to do with it than where to find more, or how to share that which we've already found.

Data can also be re-used, and the same data can be used by different people for different reasons. Say I invented a new email address. I might use that to register for a music service, where I left a footprint of my taste in music; a social media platform on which I upload photos of my baby son; and a search engine, where I indulge my fascination with reggae.

If, through that email address, a data company were able to access information about me or my friends, the music service, the social network and the search engine might all benefit from that one email address and all that is connected to it. This is different from oil. If a major oil company get to an oil field in, say, Texas, they alone will have control of the oil there - and once they've used it up, it's gone.

Legitimate fears

This points to another key difference: who controls the commodity. There are very legitimate fears about the use and abuse of personal data online - for instance, by foreign powers trying to influence elections. And very few people have a really clear idea about the digital footprint they have left online. If they did know, they might become obsessed with security. I know a few data fanatics who own several phones and indulge data-savvy habits, such as avoiding all text messages in favour of WhatsApp, which is encrypted.

But data is something which - in theory if not in practice - the user can control, and which ideally - though again the practice falls well short - spreads by consent. Going back to that oil company, it's largely up to them how they deploy the oil in the ground beneath Texas: how many barrels they take out every day, what price they sell it for, who they sell it to.

With my email address, it's up to me whether to give it to that music service, social network, or search engine. If I don't want people to know that I have an unhealthy obsession with bands such as The Wailers, The Pioneers and The Ethiopians, I can keep digitally schtum.

Now, I realise that in practice, very few people feel they have control over their personal data online; and retrieving your data isn't exactly easy. If I tried to reclaim, or wipe from the face of the earth, all the personal data that I've handed over to data companies, it'd be a full time job for the rest of my life and I'd never actually achieve it. That said, it is largely as a result of my choices that these firms have so much of my personal data.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESImage captionServers for data storage in Hafnarfjordur, Iceland, which is trying to make a name for itself in the business of data centres - warehouses that consume enormous amounts of energy to store the information of 3.2 billion internet users.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESImage captionServers for data storage in Hafnarfjordur, Iceland, which is trying to make a name for itself in the business of data centres - warehouses that consume enormous amounts of energy to store the information of 3.2 billion internet users.

The final key difference is that the data industry is much faster to evolve than the oil industry was. Innovation is in the very DNA of big data companies, some of whose lifespans are pitifully short. As a result, regulation is much harder. That briefing in The Economist actually makes the point well that a previous model of regulation may not necessarily work for these new companies, who are forever adapting. That is not to say they should not be regulated; rather, that regulating them is something we haven't yet worked out how to do.

It is because the debate over regulation of these companies is so live that I think we need to interrogate superficially attractive ideas such as 'data is the new oil'. In fact, whereas finite but plentiful oil supplied a raw material for the industrial economy, data is a super-abundant resource in a post-industrial economy. Data companies increasingly control, and redefine, the nature of our public domain, rather than power our transport, or heat our homes.

Data today has something important in common with oil a century ago. But the tech titans are more media moguls than oil barons.

It is because the debate over regulation of these companies is so live that I think we need to interrogate superficially attractive ideas such as 'data is the new oil'. In fact, whereas finite but plentiful oil supplied a raw material for the industrial economy, data is a super-abundant resource in a post-industrial economy. Data companies increasingly control, and redefine, the nature of our public domain, rather than power our transport, or heat our homes.

Data today has something important in common with oil a century ago. But the tech titans are more media moguls than oil barons.

233 Comments

233 Comments