'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label slaughter. Show all posts

Showing posts with label slaughter. Show all posts

Tuesday, 14 November 2023

Tuesday, 7 May 2019

Red Meat Republic - The Story of Beef

Exploitation and predatory pricing drove the transformation of the US beef industry – and created the model for modern agribusiness. By Joshua Specht in The Guardian

The meatpacking mogul Jonathan Ogden Armour could not abide socialist agitators. It was 1906, and Upton Sinclair had just published The Jungle, an explosive novel revealing the grim underside of the American meatpacking industry. Sinclair’s book told the tale of an immigrant family’s toil in Chicago’s slaughterhouses, tracing the family’s physical, financial and emotional collapse. The Jungle was not Armour’s only concern. The year before, the journalist Charles Edward Russell’s book The Greatest Trust in the World had detailed the greed and exploitation of a packing industry that came to the American dining table “three times a day … and extorts its tribute”.

In response to these attacks, Armour, head of the enormous Chicago-based meatpacking firm Armour & Co, took to the Saturday Evening Post to defend himself and his industry. Where critics saw filth, corruption and exploitation, Armour saw cleanliness, fairness and efficiency. If it were not for “the professional agitators of the country”, he claimed, the nation would be free to enjoy an abundance of delicious and affordable meat.

Armour and his critics could agree on this much: they lived in a world unimaginable 50 years before. In 1860, most cattle lived, died and were consumed within a few hundred miles’ radius. By 1906, an animal could be born in Texas, slaughtered in Chicago and eaten in New York. Americans rich and poor could expect to eat beef for dinner. The key aspects of modern beef production – highly centralised, meatpacker-dominated and low-cost – were all pioneered during that period.

For Armour, cheap beef and a thriving centralised meatpacking industry were the consequence of emerging technologies such as the railroad and refrigeration coupled with the business acumen of a set of honest and hard-working men like his father, Philip Danforth Armour. According to critics, however, a capitalist cabal was exploiting technological change and government corruption to bankrupt traditional butchers, sell diseased meat and impoverish the worker.

Ultimately, both views were correct. The national market for fresh beef was the culmination of a technological revolution, but it was also the result of collusion and predatory pricing. The industrial slaughterhouse was a triumph of human ingenuity as well as a site of brutal labour exploitation. Industrial beef production, with all its troubling costs and undeniable benefits, reflected seemingly contradictory realities.

Beef production would also help drive far-reaching changes in US agriculture. Fresh-fruit distribution began with the rise of the meatpackers’ refrigerator cars, which they rented to fruit and vegetable growers. Production of wheat, perhaps the US’s greatest food crop, bore the meatpackers’ mark. In order to manage animal feed costs, Armour & Co and Swift & Co invested heavily in wheat futures and controlled some of the country’s largest grain elevators. In the early 20th century, an Armour & Co promotional map announced that “the greatness of the United States is founded on agriculture”, and depicted the agricultural products of each US state, many of which moved through Armour facilities.

Beef was a paradigmatic industry for the rise of modern industrial agriculture, or agribusiness. As much as a story of science or technology, modern agriculture is a compromise between the unpredictability of nature and the rationality of capital. This was a lurching, violent process that sawmeatpackers displace the risks of blizzards, drought, disease and overproduction on to cattle ranchers. Today’s agricultural system works similarly. In poultry, processors like Perdue and Tyson use an elaborate system of contracts and required equipment and feed purchases to maximise their own profits while displacing risk on to contract farmers. This is true with crop production as well. As with 19th-century meatpacking, relatively small actors conduct the actual growing and production, while companies like Monsanto and Cargill control agricultural inputs and market access.

The transformations that remade beef production between the end of the American civil war in 1865 and the passage of the Federal Meat Inspection Act in 1906 stretched from the Great Plains to the kitchen table. Before the civil war, cattle raising was largely regional, and in most cases, the people who managed cattle out west were the same people who owned them. Then, in the 1870s and 80s, improved transport, bloody victories over the Plains Indians, and the American west’s integration into global capital markets sparked a ranching boom. Meanwhile, Chicago meatpackers pioneered centralised food processing. Using an innovative system of refrigerator cars and distribution centres, they began to distribute fresh beef nationwide. Millions of cattle were soon passing through Chicago’s slaughterhouses each year. By 1890, the Big Four meatpacking companies – Armour & Co, Swift & Co, Morris & Co and the GH Hammond Co – directly or indirectly controlled the majority of the nation’s beef and pork.

But in the 1880s, the big Chicago meatpackers faced determined opposition at every stage from slaughter to sale. Meatpackers fought with workers as they imposed a brutally exploitative labour regime. Meanwhile, attempts to transport freshly butchered beef faced opposition from railroads who found higher profits transporting live cattle east out of Chicago and to local slaughterhouses in eastern cities. Once pre-slaughtered and partially processed beef – known as “dressed beef” – reached the nation’s many cities and towns, the packers fought to displace traditional butchers and woo consumers sceptical of eating meat from an animal slaughtered a continent away.

The consequences of each of these struggles persist today. A small number of firms still control most of the country’s – and by now the world’s – beef. They draw from many comparatively small ranchers and cattle feeders, and depend on a low-paid, mostly invisible workforce. The fact that this set of relationships remains so stable, despite the public’s abstract sense that something is not quite right, is not the inevitable consequence of technological change but the direct result of the political struggles of the late 19th century.

In the slaughterhouse, someone was always willing to take your place. This could not have been far from the mind of 14-year-old Vincentz Rutkowski as he stooped, knife in hand, in a Swift & Co facility in summer 1892. For up to 10 hours each day, Vincentz trimmed tallow from cattle paunches. The job required strong workers who were low to the ground, making it ideal for boys like Rutkowski, who had the beginnings of the strength but not the size of grown men. For the first two weeks of his employment, Rutkowski shared his job with two other boys. As they became more skilled, one of the boys was fired. Another few weeks later, the other was also removed, and Rutkowski was expected to do the work of three people.

The morning that final co-worker left, on 30 June, Rutkowski fell behind the disassembly line’s frenetic pace. After just three hours of working alone, the boy failed to dodge a carcass swinging toward him. It struck his knife hand, driving the tool into his left arm near the elbow. The knife cut muscle and tendon, leaving Rutkowski with lifelong injuries.

The labour regime that led to Rutkowski’s injury was integral to large-scale meatpacking. A packinghouse was a masterpiece of technological and organisational achievement, but that was not enough to slaughter millions of cattle annually. Packing plants needed cheap, reliable and desperate labour. They found it via the combination of mass immigration and a legal regime that empowered management, checked the nascent power of unions and provided limited liability for worker injury. The Big Four’s output depended on worker quantity over worker quality.

Meatpacking lines, pioneered in the 1860s in Cincinnati’s pork packinghouses, were the first modern production lines. The innovation was that they kept products moving continuously, eliminating downtime and requiring workers to synchronise their movements to keep pace. This idea was enormously influential. In his memoirs, Henry Ford explained that his idea for continuous motion assembly “came in a general way from the overhead trolley that the Chicago packers use in dressing beef”.

A Swift and Company meatpacking house in Chicago, circa 1906. Photograph: Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

Packing plants relied on a brilliant intensification of the division of labour. This division increased productivity because it simplified slaughter tasks. Workers could then be trained quickly, and because the tasks were also synchronised, everyone had to match the pace of the fastest worker.

When cattle first entered one of these slaughterhouses, they encountered an armed man walking toward them on an overhead plank. Whether by a hammer swing to the skull or a spear thrust to the animal’s spinal column, the (usually achieved) goal was to kill with a single blow. Assistants chained the animal’s legs and dragged the carcass from the room. The carcass was hoisted into the air and brought from station to station along an overhead rail.

Next, a worker cut the animal’s throat and drained and collected its blood while another group began skinning the carcass. Even this relatively simple process was subdivided throughout the period. Initially the work of a pair, nine different workers handled skinning by 1904. Once the carcass was stripped, gutted and drained of blood, it went into another room, where highly trained butchers cut the carcass into quarters. These quarters were stored in giant refrigerated rooms to await distribution.

But profitability was not just about what happened inside slaughterhouses. It also depended on what was outside: throngs of men and women hoping to find a day’s or a week’s employment. An abundant labour supply meant the packers could easily replace anyone who balked at paltry salaries or, worse yet, tried to unionise. Similarly, productivity increases heightened the risk of worker injury, and therefore were only effective if people could be easily replaced. Fortunately for the packers, late 19th-century Chicago was full of people desperate for work.

Seasonal fluctuations and the vagaries of the nation’s cattle markets further conspired to marginalise slaughterhouse labour. Though refrigeration helped the meatpackers “defeat the seasons” and secure year-round shipping, packing remained seasonal. Packers had to reckon with cattle’s reproductive cycles, and distribution in hot weather was more expensive. The number of animals processed varied day to day and month to month. For packinghouse workers, the effect was a world in which an individual day’s labour might pay relatively well but busy days were punctuated with long stretches of little or no work. The least skilled workers might only find a few weeks or months of employment at a time.

The work was so competitive and the workers so desperate that, even when they had jobs, they often had to wait, without pay, if there were no animals to slaughter. Workers would be fired if they did not show up at a specified time before 9am, but then might wait, unpaid, until 10am or 11am for a shipment. If the delivery was very late, work might continue until late into the night.

Though the division of labour and throngs of unemployed people were crucial to operating the Big Four’s disassembly lines, these factors were not sufficient to maintain a relentless production pace. This required intervention directly on the line. Fortunately for the packers, they could exploit a core aspect of continuous-motion processing: if one person went faster, everyone had to go faster. The meatpackers used pace-setters to force other workers to increase their speed. The packers would pay this select group – roughly one in 10 workers – higher wages and offer secure positions that they only kept if they maintained a rapid pace, forcing the rest of the line to keep up. These pace-setters were resented by their co-workers, and were a vital management tool.

Close supervision of foremen was equally important. Management kept statistics on production-line output, and overseers who slipped in production could lose their jobs. This encouraged foremen to use tactics that management did not want to explicitly support. According to one retired foreman, he was “always trying to cut down wages in every possible way … some of [the foremen] got a commission on all expenses they could save below a certain point”. Though union officials vilified foremen, their jobs were only marginally less tenuous than those of their underlings.

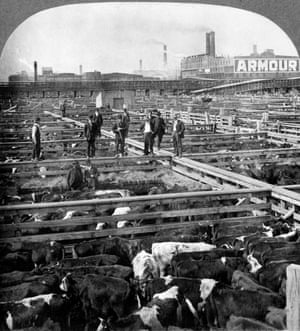

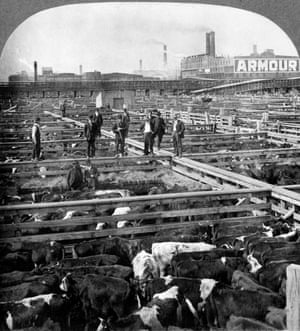

Union Stock Yard in Chicago in 1909. Photograph: Science History Images/Alamy

The effectiveness of de-skilling on the disassembly line rested on an increase in the wages of a few highly skilled positions. Though these workers individually made more money, their employers secured a precipitous decrease in average wages. Previously, a gang composed entirely of general-purpose butchers might all be paid 35 cents an hour. In the new regime, a few highly specialised butchers would receive 50 cents or more an hour, but the majority of other workers would be paid much less than 35 cents. Highly paid workers were given the only jobs in which costly mistakes could be made – damage to hides or expensive cuts of meat – protecting against mistakes or sabotage from the irregularly employed workers. The packers also believed (sometimes erroneously) that the highly paid workers – popularly known as the “butcher aristocracy” – would be more loyal to management and less willing to cooperate with unionisation attempts.

The overall trend was an incredible intensification of output. Splitters, one of the most skilled positions, provide a good example. The economist John Commons wrote that in 1884, “five splitters in a certain gang would get out 800 cattle in 10 hours, or 16 per hour for each man, the wages being 45 cents. In 1894 the speed had been increased so that four splitters got out 1,200 in 10 hours, or 30 per hour for each man – an increase of nearly 100% in 10 years.” Even as the pace increased, the process of de-skilling ensured that wages were constantly moving downward, forcing employees to work harder for less money.

The fact that meatpacking’s profitability depended on a brutal labour regime meant conflicts between labour and management were ongoing, and at times violent. For workers, strikes during the 1880s and 90s were largely unsuccessful. This was the result of state support for management, a willing pool of replacement workers and extreme hostility to any attempts to organise. At the first sign of unrest, Chicago packers would recruit replacement workers from across the US and threaten to permanently fire and blacklist anyone associated with labour organisers. But state support mattered most of all; during an 1886 fight, for instance, authorities “garrisoned over 1,000 men … to preserve order and protect property”. Even when these troops did not clash with strikers, it had a chilling effect on attempts to organise. Ultimately, packinghouse workers could not organise effectively until the very end of the 19th century.

The genius of the disassembly line was not merely in creating productivity gains through the division of labour; it was also that it simplified labour enough that the Big Four could benefit from a growing surplus of workers and a business-friendly legal regime. If the meatpackers needed purely skilled labour, they could not exploit desperate throngs outside their gates. If a new worker could be trained in hours and government was willing to break strikes and limit injury liability, workers became disposable. This enabled the dangerous – and profitable – increases in production speed that maimed Vincentz Rutkowski.

Centralisation of cattle slaughter in Chicago promised high profits. Chicago’s stockyards had started as a clearinghouse for cattle – a point from which animals were shipped live to cities around the country. But when an animal is shipped live, almost 40% of the travelling weight is blood, bones, hide and other inedible parts. The small slaughterhouses and butchers that bought live animals in New York or Boston could sell some of these by-products to tanners or fertiliser manufacturers, but their ability to do so was limited. If the animals could be slaughtered in Chicago, the large packinghouses could realise massive economies of scale on the by-products. In fact, these firms could undersell local slaughterhouses on the actual meat and make their profits on the by-products.

This model only became possible with refinements in refrigerated shipping technology, starting in the 1870s. Yet simply because technology created a possibility did not make its adoption inevitable. Refrigeration sparked a nearly decade-long conflict between the meatpackers and the railroads. American railroads had invested heavily in railcars and other equipment for shipping live cattle, and fought dressed-beef shipment tonne by tonne, charging different prices for moving a given weight of dressed beef from a similar weight of live cattle. They justified this difference by claiming their goal was to provide the same final cost for beef to consumers – what the railroads called a “principle of neutrality”.

Since beef from animals slaughtered locally was more expensive than Chicago dressed beef, the railroads would charge the Chicago packers more to even things out. This would protect railroad investments by eliminating the packers’ edge, and it could all be justified as “neutral”. Though this succeeded for a time, the packers would defeat this strategy by taking a circuitous route along Canada’s Grand Trunk Railway, a line that was happy to accept dressed-beef business it had no chance of securing otherwise.

Eventually, American railroads abandoned their differential pricing as they saw the collapse of live cattle shipping and became greedy for a piece of the burgeoning dressed-beef trade. But even this was not enough to secure the dominance of the Chicago houses. They also had to contend with local butchers.

In 1889 Henry Barber entered Ramsey County, Minnesota, with 100lb of contraband: fresh beef from an animal slaughtered in Chicago. Barber was no fly-by-night butcher, and was well aware of an 1889 law requiring all meat sold in Minnesota to be inspected locally prior to slaughter. Shortly after arriving, he was arrested, convicted and sentenced to 30 days in jail. But with the support of his employer, Armour & Co, Barber aggressively challenged the local inspection measure.

‘Cows carry flesh, but they carry personality too’: the hard lessons of farming

Today, most local butchers have gone bankrupt and marginal ranchers have had little choice but to accept their marginality. In the US, an increasingly punitive immigration regime makes slaughterhouse work ever more precarious, and “ag-gag” laws that define animal-rights activism as terrorism keep slaughterhouses out of the public eye. The result is that our means of producing our food can seem inevitable, whatever creeping sense of unease consumers might feel. But the history of the beef industry reminds us that this method of producing food is a question of politics and political economy, rather than technology and demographics. Alternate possibilities remain hazy, but if we understand this story as one of political economy, we might be able to fulfil Armour & Company’s old credo – “We feed the world”– using a more equitable system.

The meatpacking mogul Jonathan Ogden Armour could not abide socialist agitators. It was 1906, and Upton Sinclair had just published The Jungle, an explosive novel revealing the grim underside of the American meatpacking industry. Sinclair’s book told the tale of an immigrant family’s toil in Chicago’s slaughterhouses, tracing the family’s physical, financial and emotional collapse. The Jungle was not Armour’s only concern. The year before, the journalist Charles Edward Russell’s book The Greatest Trust in the World had detailed the greed and exploitation of a packing industry that came to the American dining table “three times a day … and extorts its tribute”.

In response to these attacks, Armour, head of the enormous Chicago-based meatpacking firm Armour & Co, took to the Saturday Evening Post to defend himself and his industry. Where critics saw filth, corruption and exploitation, Armour saw cleanliness, fairness and efficiency. If it were not for “the professional agitators of the country”, he claimed, the nation would be free to enjoy an abundance of delicious and affordable meat.

Armour and his critics could agree on this much: they lived in a world unimaginable 50 years before. In 1860, most cattle lived, died and were consumed within a few hundred miles’ radius. By 1906, an animal could be born in Texas, slaughtered in Chicago and eaten in New York. Americans rich and poor could expect to eat beef for dinner. The key aspects of modern beef production – highly centralised, meatpacker-dominated and low-cost – were all pioneered during that period.

For Armour, cheap beef and a thriving centralised meatpacking industry were the consequence of emerging technologies such as the railroad and refrigeration coupled with the business acumen of a set of honest and hard-working men like his father, Philip Danforth Armour. According to critics, however, a capitalist cabal was exploiting technological change and government corruption to bankrupt traditional butchers, sell diseased meat and impoverish the worker.

Ultimately, both views were correct. The national market for fresh beef was the culmination of a technological revolution, but it was also the result of collusion and predatory pricing. The industrial slaughterhouse was a triumph of human ingenuity as well as a site of brutal labour exploitation. Industrial beef production, with all its troubling costs and undeniable benefits, reflected seemingly contradictory realities.

Beef production would also help drive far-reaching changes in US agriculture. Fresh-fruit distribution began with the rise of the meatpackers’ refrigerator cars, which they rented to fruit and vegetable growers. Production of wheat, perhaps the US’s greatest food crop, bore the meatpackers’ mark. In order to manage animal feed costs, Armour & Co and Swift & Co invested heavily in wheat futures and controlled some of the country’s largest grain elevators. In the early 20th century, an Armour & Co promotional map announced that “the greatness of the United States is founded on agriculture”, and depicted the agricultural products of each US state, many of which moved through Armour facilities.

Beef was a paradigmatic industry for the rise of modern industrial agriculture, or agribusiness. As much as a story of science or technology, modern agriculture is a compromise between the unpredictability of nature and the rationality of capital. This was a lurching, violent process that sawmeatpackers displace the risks of blizzards, drought, disease and overproduction on to cattle ranchers. Today’s agricultural system works similarly. In poultry, processors like Perdue and Tyson use an elaborate system of contracts and required equipment and feed purchases to maximise their own profits while displacing risk on to contract farmers. This is true with crop production as well. As with 19th-century meatpacking, relatively small actors conduct the actual growing and production, while companies like Monsanto and Cargill control agricultural inputs and market access.

The transformations that remade beef production between the end of the American civil war in 1865 and the passage of the Federal Meat Inspection Act in 1906 stretched from the Great Plains to the kitchen table. Before the civil war, cattle raising was largely regional, and in most cases, the people who managed cattle out west were the same people who owned them. Then, in the 1870s and 80s, improved transport, bloody victories over the Plains Indians, and the American west’s integration into global capital markets sparked a ranching boom. Meanwhile, Chicago meatpackers pioneered centralised food processing. Using an innovative system of refrigerator cars and distribution centres, they began to distribute fresh beef nationwide. Millions of cattle were soon passing through Chicago’s slaughterhouses each year. By 1890, the Big Four meatpacking companies – Armour & Co, Swift & Co, Morris & Co and the GH Hammond Co – directly or indirectly controlled the majority of the nation’s beef and pork.

But in the 1880s, the big Chicago meatpackers faced determined opposition at every stage from slaughter to sale. Meatpackers fought with workers as they imposed a brutally exploitative labour regime. Meanwhile, attempts to transport freshly butchered beef faced opposition from railroads who found higher profits transporting live cattle east out of Chicago and to local slaughterhouses in eastern cities. Once pre-slaughtered and partially processed beef – known as “dressed beef” – reached the nation’s many cities and towns, the packers fought to displace traditional butchers and woo consumers sceptical of eating meat from an animal slaughtered a continent away.

The consequences of each of these struggles persist today. A small number of firms still control most of the country’s – and by now the world’s – beef. They draw from many comparatively small ranchers and cattle feeders, and depend on a low-paid, mostly invisible workforce. The fact that this set of relationships remains so stable, despite the public’s abstract sense that something is not quite right, is not the inevitable consequence of technological change but the direct result of the political struggles of the late 19th century.

In the slaughterhouse, someone was always willing to take your place. This could not have been far from the mind of 14-year-old Vincentz Rutkowski as he stooped, knife in hand, in a Swift & Co facility in summer 1892. For up to 10 hours each day, Vincentz trimmed tallow from cattle paunches. The job required strong workers who were low to the ground, making it ideal for boys like Rutkowski, who had the beginnings of the strength but not the size of grown men. For the first two weeks of his employment, Rutkowski shared his job with two other boys. As they became more skilled, one of the boys was fired. Another few weeks later, the other was also removed, and Rutkowski was expected to do the work of three people.

The morning that final co-worker left, on 30 June, Rutkowski fell behind the disassembly line’s frenetic pace. After just three hours of working alone, the boy failed to dodge a carcass swinging toward him. It struck his knife hand, driving the tool into his left arm near the elbow. The knife cut muscle and tendon, leaving Rutkowski with lifelong injuries.

The labour regime that led to Rutkowski’s injury was integral to large-scale meatpacking. A packinghouse was a masterpiece of technological and organisational achievement, but that was not enough to slaughter millions of cattle annually. Packing plants needed cheap, reliable and desperate labour. They found it via the combination of mass immigration and a legal regime that empowered management, checked the nascent power of unions and provided limited liability for worker injury. The Big Four’s output depended on worker quantity over worker quality.

Meatpacking lines, pioneered in the 1860s in Cincinnati’s pork packinghouses, were the first modern production lines. The innovation was that they kept products moving continuously, eliminating downtime and requiring workers to synchronise their movements to keep pace. This idea was enormously influential. In his memoirs, Henry Ford explained that his idea for continuous motion assembly “came in a general way from the overhead trolley that the Chicago packers use in dressing beef”.

A Swift and Company meatpacking house in Chicago, circa 1906. Photograph: Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

Packing plants relied on a brilliant intensification of the division of labour. This division increased productivity because it simplified slaughter tasks. Workers could then be trained quickly, and because the tasks were also synchronised, everyone had to match the pace of the fastest worker.

When cattle first entered one of these slaughterhouses, they encountered an armed man walking toward them on an overhead plank. Whether by a hammer swing to the skull or a spear thrust to the animal’s spinal column, the (usually achieved) goal was to kill with a single blow. Assistants chained the animal’s legs and dragged the carcass from the room. The carcass was hoisted into the air and brought from station to station along an overhead rail.

Next, a worker cut the animal’s throat and drained and collected its blood while another group began skinning the carcass. Even this relatively simple process was subdivided throughout the period. Initially the work of a pair, nine different workers handled skinning by 1904. Once the carcass was stripped, gutted and drained of blood, it went into another room, where highly trained butchers cut the carcass into quarters. These quarters were stored in giant refrigerated rooms to await distribution.

But profitability was not just about what happened inside slaughterhouses. It also depended on what was outside: throngs of men and women hoping to find a day’s or a week’s employment. An abundant labour supply meant the packers could easily replace anyone who balked at paltry salaries or, worse yet, tried to unionise. Similarly, productivity increases heightened the risk of worker injury, and therefore were only effective if people could be easily replaced. Fortunately for the packers, late 19th-century Chicago was full of people desperate for work.

Seasonal fluctuations and the vagaries of the nation’s cattle markets further conspired to marginalise slaughterhouse labour. Though refrigeration helped the meatpackers “defeat the seasons” and secure year-round shipping, packing remained seasonal. Packers had to reckon with cattle’s reproductive cycles, and distribution in hot weather was more expensive. The number of animals processed varied day to day and month to month. For packinghouse workers, the effect was a world in which an individual day’s labour might pay relatively well but busy days were punctuated with long stretches of little or no work. The least skilled workers might only find a few weeks or months of employment at a time.

The work was so competitive and the workers so desperate that, even when they had jobs, they often had to wait, without pay, if there were no animals to slaughter. Workers would be fired if they did not show up at a specified time before 9am, but then might wait, unpaid, until 10am or 11am for a shipment. If the delivery was very late, work might continue until late into the night.

Though the division of labour and throngs of unemployed people were crucial to operating the Big Four’s disassembly lines, these factors were not sufficient to maintain a relentless production pace. This required intervention directly on the line. Fortunately for the packers, they could exploit a core aspect of continuous-motion processing: if one person went faster, everyone had to go faster. The meatpackers used pace-setters to force other workers to increase their speed. The packers would pay this select group – roughly one in 10 workers – higher wages and offer secure positions that they only kept if they maintained a rapid pace, forcing the rest of the line to keep up. These pace-setters were resented by their co-workers, and were a vital management tool.

Close supervision of foremen was equally important. Management kept statistics on production-line output, and overseers who slipped in production could lose their jobs. This encouraged foremen to use tactics that management did not want to explicitly support. According to one retired foreman, he was “always trying to cut down wages in every possible way … some of [the foremen] got a commission on all expenses they could save below a certain point”. Though union officials vilified foremen, their jobs were only marginally less tenuous than those of their underlings.

Union Stock Yard in Chicago in 1909. Photograph: Science History Images/Alamy

The effectiveness of de-skilling on the disassembly line rested on an increase in the wages of a few highly skilled positions. Though these workers individually made more money, their employers secured a precipitous decrease in average wages. Previously, a gang composed entirely of general-purpose butchers might all be paid 35 cents an hour. In the new regime, a few highly specialised butchers would receive 50 cents or more an hour, but the majority of other workers would be paid much less than 35 cents. Highly paid workers were given the only jobs in which costly mistakes could be made – damage to hides or expensive cuts of meat – protecting against mistakes or sabotage from the irregularly employed workers. The packers also believed (sometimes erroneously) that the highly paid workers – popularly known as the “butcher aristocracy” – would be more loyal to management and less willing to cooperate with unionisation attempts.

The overall trend was an incredible intensification of output. Splitters, one of the most skilled positions, provide a good example. The economist John Commons wrote that in 1884, “five splitters in a certain gang would get out 800 cattle in 10 hours, or 16 per hour for each man, the wages being 45 cents. In 1894 the speed had been increased so that four splitters got out 1,200 in 10 hours, or 30 per hour for each man – an increase of nearly 100% in 10 years.” Even as the pace increased, the process of de-skilling ensured that wages were constantly moving downward, forcing employees to work harder for less money.

The fact that meatpacking’s profitability depended on a brutal labour regime meant conflicts between labour and management were ongoing, and at times violent. For workers, strikes during the 1880s and 90s were largely unsuccessful. This was the result of state support for management, a willing pool of replacement workers and extreme hostility to any attempts to organise. At the first sign of unrest, Chicago packers would recruit replacement workers from across the US and threaten to permanently fire and blacklist anyone associated with labour organisers. But state support mattered most of all; during an 1886 fight, for instance, authorities “garrisoned over 1,000 men … to preserve order and protect property”. Even when these troops did not clash with strikers, it had a chilling effect on attempts to organise. Ultimately, packinghouse workers could not organise effectively until the very end of the 19th century.

The genius of the disassembly line was not merely in creating productivity gains through the division of labour; it was also that it simplified labour enough that the Big Four could benefit from a growing surplus of workers and a business-friendly legal regime. If the meatpackers needed purely skilled labour, they could not exploit desperate throngs outside their gates. If a new worker could be trained in hours and government was willing to break strikes and limit injury liability, workers became disposable. This enabled the dangerous – and profitable – increases in production speed that maimed Vincentz Rutkowski.

Centralisation of cattle slaughter in Chicago promised high profits. Chicago’s stockyards had started as a clearinghouse for cattle – a point from which animals were shipped live to cities around the country. But when an animal is shipped live, almost 40% of the travelling weight is blood, bones, hide and other inedible parts. The small slaughterhouses and butchers that bought live animals in New York or Boston could sell some of these by-products to tanners or fertiliser manufacturers, but their ability to do so was limited. If the animals could be slaughtered in Chicago, the large packinghouses could realise massive economies of scale on the by-products. In fact, these firms could undersell local slaughterhouses on the actual meat and make their profits on the by-products.

This model only became possible with refinements in refrigerated shipping technology, starting in the 1870s. Yet simply because technology created a possibility did not make its adoption inevitable. Refrigeration sparked a nearly decade-long conflict between the meatpackers and the railroads. American railroads had invested heavily in railcars and other equipment for shipping live cattle, and fought dressed-beef shipment tonne by tonne, charging different prices for moving a given weight of dressed beef from a similar weight of live cattle. They justified this difference by claiming their goal was to provide the same final cost for beef to consumers – what the railroads called a “principle of neutrality”.

Since beef from animals slaughtered locally was more expensive than Chicago dressed beef, the railroads would charge the Chicago packers more to even things out. This would protect railroad investments by eliminating the packers’ edge, and it could all be justified as “neutral”. Though this succeeded for a time, the packers would defeat this strategy by taking a circuitous route along Canada’s Grand Trunk Railway, a line that was happy to accept dressed-beef business it had no chance of securing otherwise.

Eventually, American railroads abandoned their differential pricing as they saw the collapse of live cattle shipping and became greedy for a piece of the burgeoning dressed-beef trade. But even this was not enough to secure the dominance of the Chicago houses. They also had to contend with local butchers.

In 1889 Henry Barber entered Ramsey County, Minnesota, with 100lb of contraband: fresh beef from an animal slaughtered in Chicago. Barber was no fly-by-night butcher, and was well aware of an 1889 law requiring all meat sold in Minnesota to be inspected locally prior to slaughter. Shortly after arriving, he was arrested, convicted and sentenced to 30 days in jail. But with the support of his employer, Armour & Co, Barber aggressively challenged the local inspection measure.

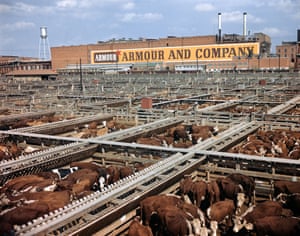

A cattle stockyard in Texas in the 1960s. Photograph: ClassicStock/Alamy

Barber’s arrest was part of a plan to provoke a fight over the Minnesota law, which Armour & Co had lobbied against since it was first drawn up. In federal court, Barber’s lawyers alleged that the statute under which he was convicted violated federal authority over interstate commerce, as well as the US constitution’s privileges and immunities clause. The case would eventually reach the supreme court.

At trial, the state argued that without local, on-the-hoof inspection it was impossible to know if meat had come from a diseased animal. Local inspection was therefore a reasonable part of the state’s police power. Of course, if this argument was upheld, the Chicago houses would no longer be able to ship their goods to any unfriendly state. In response, Barber’s counsel argued that the Minnesota law was a protectionist measure that discriminated against out-of-state butchers. There was no reason meat could not be adequately inspected in Chicago before being sold elsewhere. In Minnesota v Barber (1890), the supreme court ruled the statute unconstitutional and ordered Barber’s release. Armour & Co would go on to dominate the local market.

The Barber ruling was a pivotal moment in a longer fight on the part of the Big Four to secure national distribution. The Minnesota law, and others like it across the country, were fronts in a war waged by local butchers to protect their trade against the encroachment of the “dressed-beef men”. The rise of the Chicago meatpackers was not a gradual process of newer practices displacing old, but a wrenching process of big packers strong-arming and bankrupting smaller competitors. The Barber decision made these fights possible, but it did not make victory inevitable. It was on the back of hundreds of small victories – in rural and urban communities across the US – that the packers built their enormous profits.

Armour and the other big packers did not want to deal directly with customers. That required knowledge of local markets and represented a considerable amount of risk. Instead, they hoped to replace wholesalers, who slaughtered cattle for sale to retail butchers. The Chicago houses wanted local butchers to focus exclusively on selling meat; the packers would handle the rest.

When the packers first entered an area, they wooed a respected butcher. If the butcher would agree to buy from the Chicago houses, he could secure extremely generous rates. But if the local butcher refused these advances, the packers declared war. For example, when the Chicago houses entered Pittsburgh, they approached the veteran butcher William Peters. When he refused to work with Armour & Co, Peters later explained, the Chicago firm’s agent told him: “Mr Peters, if you butchers don’t take hold of it [dressed beef], we are going to open shops throughout the city.” Still, Peters resisted and Armour went on to open its own shops, underselling Pittsburgh’s butchers. Peters told investigators that he and his colleagues “are working for glory now. We do not work for any profit … we have been working for glory for the past three or four years, ever since those fellows came into our town”. Meanwhile, Armour’s share of the Pittsburgh market continued to grow.

Facing these kinds of tactics in cities around the country, local butchers formed protective associations to fight the Chicago houses. Though many associations were local, the Butchers’ National Protective Association of the United States of America aspired to “unite in one brotherhood all butchers and persons engaged in dealing in butchers’ stock”. Organised in 1887, the association pledged to “protect their common interests and those of the general public” through a focus on sanitary conditions. Health concerns were an issue on which traditional butchers could oppose the Chicago houses while appealing to consumers’ collective good. They argued that the Big Four “disregard the public good and endanger the health of the people by selling, for human food, diseased, tainted and other unwholesome meat”. The association further promised to oppose price manipulation of a “staple and indispensable article of human food”.

These associations pushed what amounted to a protectionist agenda using food contamination as a justification. On the state and local level, associations demanded local inspection before slaughter, as was the case with the Minnesota law that Henry Barber challenged. Decentralising slaughter would make wholesale butchering again dependent on local knowledge that the packers could not acquire from Chicago.

But again the packers successfully challenged these measures in the courts. Though the specifics varied by case, judges generally affirmed the argument that local, on-the-hoof inspection violated the constitution’s interstate commerce clause, and often accepted that inspection did not need to be local to ensure safe food. Animals could be inspected in Chicago before slaughter and then the meat itself could be inspected locally. This approach would address public fears about sanitary meat, but without a corresponding benefit to local butchers. Lacking legal recourse and finding little support from consumers excited about low-cost beef, local wholesalers lost more and more ground to the Chicago houses until they disappeared almost entirely.

Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle would become the most famous protest novel of the 20th century. By revealing brutal labour exploitation and stomach-turning slaughterhouse filth, the novel helped spur the passage of the Federal Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. But The Jungle’s heart-wrenching critique of industrial capitalism was lost on readers more worried about the rat faeces that, according to Sinclair, contaminated their sausage. Sinclair later observed: “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.” He hoped for socialist revolution, but had to settle for accurate food labelling.

The industry’s defence against striking workers, angry butchers and bankrupt ranchers – namely, that the new system of industrial production served a higher good – resonated with the public. Abstractly, Americans were worried about the plight of slaughterhouse workers, but they were also wary of those same workers marching in the streets. Similarly, they cared about the struggles of ranchers and local butchers, but also had to worry about their wallets. If packers could provide low prices and reassure the public that their meat was safe, consumers would be happy.

The Big Four meatpacking firms came to control the majority of the US’s beef within a fairly brief period –about 15 years – as a set of relationships that once appeared unnatural began to appear inevitable. Intense de-skilling in slaughterhouse labour only became accepted once organised labour was thwarted, leaving packinghouse labour largely invisible to this day. The slaughter of meat in one place for consumption and sale elsewhere only ceased to appear “artificial and abnormal” once butchers’ protective associations disbanded, and once lawmakers and the public accepted that this centralised industrial system was necessary to provide cheap beef to the people.

These developments are taken for granted now, but they were the product of struggles that could have resulted in radically different standards of production. The beef industry that was established in this period would shape food production throughout the 20th century. There were more major shifts – ranging from trucking-driven decentralisation to the rise of fast food – but the broad strokes would remain the same. Much of the environmental and economic risk of food production would be displaced on to struggling ranchers and farmers, while processors and packers would make money in good times and bad. Benefit to an abstract consumer good would continue to justify the industry’s high environmental and social costs.

Barber’s arrest was part of a plan to provoke a fight over the Minnesota law, which Armour & Co had lobbied against since it was first drawn up. In federal court, Barber’s lawyers alleged that the statute under which he was convicted violated federal authority over interstate commerce, as well as the US constitution’s privileges and immunities clause. The case would eventually reach the supreme court.

At trial, the state argued that without local, on-the-hoof inspection it was impossible to know if meat had come from a diseased animal. Local inspection was therefore a reasonable part of the state’s police power. Of course, if this argument was upheld, the Chicago houses would no longer be able to ship their goods to any unfriendly state. In response, Barber’s counsel argued that the Minnesota law was a protectionist measure that discriminated against out-of-state butchers. There was no reason meat could not be adequately inspected in Chicago before being sold elsewhere. In Minnesota v Barber (1890), the supreme court ruled the statute unconstitutional and ordered Barber’s release. Armour & Co would go on to dominate the local market.

The Barber ruling was a pivotal moment in a longer fight on the part of the Big Four to secure national distribution. The Minnesota law, and others like it across the country, were fronts in a war waged by local butchers to protect their trade against the encroachment of the “dressed-beef men”. The rise of the Chicago meatpackers was not a gradual process of newer practices displacing old, but a wrenching process of big packers strong-arming and bankrupting smaller competitors. The Barber decision made these fights possible, but it did not make victory inevitable. It was on the back of hundreds of small victories – in rural and urban communities across the US – that the packers built their enormous profits.

Armour and the other big packers did not want to deal directly with customers. That required knowledge of local markets and represented a considerable amount of risk. Instead, they hoped to replace wholesalers, who slaughtered cattle for sale to retail butchers. The Chicago houses wanted local butchers to focus exclusively on selling meat; the packers would handle the rest.

When the packers first entered an area, they wooed a respected butcher. If the butcher would agree to buy from the Chicago houses, he could secure extremely generous rates. But if the local butcher refused these advances, the packers declared war. For example, when the Chicago houses entered Pittsburgh, they approached the veteran butcher William Peters. When he refused to work with Armour & Co, Peters later explained, the Chicago firm’s agent told him: “Mr Peters, if you butchers don’t take hold of it [dressed beef], we are going to open shops throughout the city.” Still, Peters resisted and Armour went on to open its own shops, underselling Pittsburgh’s butchers. Peters told investigators that he and his colleagues “are working for glory now. We do not work for any profit … we have been working for glory for the past three or four years, ever since those fellows came into our town”. Meanwhile, Armour’s share of the Pittsburgh market continued to grow.

Facing these kinds of tactics in cities around the country, local butchers formed protective associations to fight the Chicago houses. Though many associations were local, the Butchers’ National Protective Association of the United States of America aspired to “unite in one brotherhood all butchers and persons engaged in dealing in butchers’ stock”. Organised in 1887, the association pledged to “protect their common interests and those of the general public” through a focus on sanitary conditions. Health concerns were an issue on which traditional butchers could oppose the Chicago houses while appealing to consumers’ collective good. They argued that the Big Four “disregard the public good and endanger the health of the people by selling, for human food, diseased, tainted and other unwholesome meat”. The association further promised to oppose price manipulation of a “staple and indispensable article of human food”.

These associations pushed what amounted to a protectionist agenda using food contamination as a justification. On the state and local level, associations demanded local inspection before slaughter, as was the case with the Minnesota law that Henry Barber challenged. Decentralising slaughter would make wholesale butchering again dependent on local knowledge that the packers could not acquire from Chicago.

But again the packers successfully challenged these measures in the courts. Though the specifics varied by case, judges generally affirmed the argument that local, on-the-hoof inspection violated the constitution’s interstate commerce clause, and often accepted that inspection did not need to be local to ensure safe food. Animals could be inspected in Chicago before slaughter and then the meat itself could be inspected locally. This approach would address public fears about sanitary meat, but without a corresponding benefit to local butchers. Lacking legal recourse and finding little support from consumers excited about low-cost beef, local wholesalers lost more and more ground to the Chicago houses until they disappeared almost entirely.

Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle would become the most famous protest novel of the 20th century. By revealing brutal labour exploitation and stomach-turning slaughterhouse filth, the novel helped spur the passage of the Federal Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. But The Jungle’s heart-wrenching critique of industrial capitalism was lost on readers more worried about the rat faeces that, according to Sinclair, contaminated their sausage. Sinclair later observed: “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.” He hoped for socialist revolution, but had to settle for accurate food labelling.

The industry’s defence against striking workers, angry butchers and bankrupt ranchers – namely, that the new system of industrial production served a higher good – resonated with the public. Abstractly, Americans were worried about the plight of slaughterhouse workers, but they were also wary of those same workers marching in the streets. Similarly, they cared about the struggles of ranchers and local butchers, but also had to worry about their wallets. If packers could provide low prices and reassure the public that their meat was safe, consumers would be happy.

The Big Four meatpacking firms came to control the majority of the US’s beef within a fairly brief period –about 15 years – as a set of relationships that once appeared unnatural began to appear inevitable. Intense de-skilling in slaughterhouse labour only became accepted once organised labour was thwarted, leaving packinghouse labour largely invisible to this day. The slaughter of meat in one place for consumption and sale elsewhere only ceased to appear “artificial and abnormal” once butchers’ protective associations disbanded, and once lawmakers and the public accepted that this centralised industrial system was necessary to provide cheap beef to the people.

These developments are taken for granted now, but they were the product of struggles that could have resulted in radically different standards of production. The beef industry that was established in this period would shape food production throughout the 20th century. There were more major shifts – ranging from trucking-driven decentralisation to the rise of fast food – but the broad strokes would remain the same. Much of the environmental and economic risk of food production would be displaced on to struggling ranchers and farmers, while processors and packers would make money in good times and bad. Benefit to an abstract consumer good would continue to justify the industry’s high environmental and social costs.

‘Cows carry flesh, but they carry personality too’: the hard lessons of farming

Today, most local butchers have gone bankrupt and marginal ranchers have had little choice but to accept their marginality. In the US, an increasingly punitive immigration regime makes slaughterhouse work ever more precarious, and “ag-gag” laws that define animal-rights activism as terrorism keep slaughterhouses out of the public eye. The result is that our means of producing our food can seem inevitable, whatever creeping sense of unease consumers might feel. But the history of the beef industry reminds us that this method of producing food is a question of politics and political economy, rather than technology and demographics. Alternate possibilities remain hazy, but if we understand this story as one of political economy, we might be able to fulfil Armour & Company’s old credo – “We feed the world”– using a more equitable system.

Wednesday, 8 November 2017

Farook And The Art of Selectivity

Anand Ranganathan in News Laundry

You believe what you see, but unfortunately what you see is written by those who see what they believe.

A recent article by columnist Sadanand Dhume is proof if ever it was needed, that Objectivity is a metallic object that must be left behind before the writer passes through the op-ed threshold. All good now. Next!

Biases don’t beep.

The present article is not a rebuttal but, rather, an attempt to understand, using Dhume’s column, our fascination – both as writers and readers – with selectivity. To be sure, Dhume has written what needs to be read. He has highlighted the gross fraud perpetrated by the present Bharatiya Janata Party government, on freedom of speech, on the right to life, on the rule of law, and, to an exaggerated extent, on what all of us think India should be or become.

So where has he erred? To put it simply, here: Dhume has hidden more than he has revealed. He has indulged in selectivity, an attribute none other than BR Ambedkar warned us of 75 years ago. Explaining why selectivity is damaging, he wrote:

"The social evils which characterize the Hindu Society, have been well known. The publication of 'Mother India' by Miss Mayo gave these evils the widest publicity. But while 'Mother India' served the purpose of exposing the evils and calling their authors at the bar of the world to answer for their sins, it created the unfortunate impression throughout the world that while the Hindus were grovelling in the mud of these social evils and were conservative, the Muslims in India were free from them, and as compared to the Hindus, were a progressive people. That, such an impression should prevail, is surprising to those who know the Muslim Society in India at close quarters."

Ambedkar detested the evil orthodoxy of the Hindu society, exposed the casteist and bigoted nature of many ancient Hindu texts, spoke authoritatively on Hinduism, brought to light its numerous ills, left its fold to become a Buddhist; and yet, here was the same man warning us of being selective against Hinduism and Hindu society. Such was his greatness and unshakable belief to 'Do the Right Thing'.

It is astonishing how prescient, and relevant, Ambedkar’s words are even today; not at all astonishing that we discard them with the chirpy tediousness of a CISF body-frisker. Subjectivity brings us eyeballs; Objectivity brings us calm and rational thinking. Precisely the reason why hunched-over emotional beings hunting for fist-sized stones to pelt prefer the former.

Dhume writes with the immediacy of a columnist who understands, like all good columnists do, that his writings would the day after be used to wrap kachoris by the neighbourhood halwai. He is what one would call a modern writer – aware, alert, and receptive to criticism; a social media animal who tries to learn from his trolls and critics, knowing well the worth of this engagement as a self-correcting measure. A Twitter handle laden with followers bends.

Occasionally, though, Dhume gives in to a closed set of arty dunderheads who stand in the middle of summer braving scalding loo to admire the coming of age of a frangipani in a TV studio carpark. These would be the seers who think the world sucks on their analysis and interpretation like an emaciated leech. They drench the newspaper centrespreads and seal the primetime debates at will. Their word makes no sense but it is final. Subjectivity and selectivity are their calling cards. Dhume's last column suggests he was in their company.

Dhume claims personal liberties are shrinking under the present government, coming to this generalised conclusion from his wholly justified condemnation of the religious zealots who go by the moniker, Gau Rakshaks. These criminals are seemingly running amok, doubtless comforted by an overseeing government that is, outwardly at least, non-violently fanatical about saving cows. The almost complete lack of law enforcement resulting from fear of political masters, coupled with the cushion the overseers provide through their obsession with saving the Gau, is precisely the deadly combination the extremists cherish and take comfort in. This author had written previously on their barbarity and criminality. Many other have, too.

The Gau Rakshak menace is not a recent phenomena but one that is increasingly in the news. That said, an objective reading is the need of the hour, especially when it comes to sweeping psychoanalysis.

While Dhume rightly criticises the BJP and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh for zealously promoting the idea of a cow-slaughter ban, he should have mentioned that in doing so, these organisations are only following the ardent views of none other than Mahatma Gandhi and Vinobha Bhave, who incidentally went on a fast unto death unless his call for a pan-India cow slaughter ban was acceded to. Dhume should also have mentioned that the ban on cow slaughter was first implemented, and rigorously imposed in most Indian states, by the Congress party, so much so that as recently as 2015 Harish Rawat, a sitting Congress Chief Minister of Uttarakhand thundered. “Anyone who kills cows, no matter which community he belongs to is India's biggest enemy and has no right to live in the country.”

That is correct. India's biggest enemy. Not Pakistan or China but a cow-slaughterer.

The fools of the BJP are following the fools of the Congress, only more stridently because this is what fools do. To miss this facet of our daily political drudgery is to give the impression that things are happening for the first time, that the phrase déjà vu is Martian gobbledygook and not something invented by earthlings.

Dhume then talks of a deeper malaise, suggesting that under the present government, personal liberties are shrinking. Again, while Dhume rightly criticises the BJP for contributing to this, what undoubtedly is a malaise, he is silent on the fact that most of our personal liberties have been shrunk already, and to the extent they don't fit our bloated bodies anymore.

Tellingly, much of the shrinking has been carried out by the Congress. One doesn't need to go as far back as Nehru, who jailed the famous poet Majrooh for composing a song lampooning him, and amended the Article 19 (1) to steal more of the freedom away from the speech; one only needs to look at Congress' recent history. From banning films to censoring them heavily, from banning books that offended dynasty sycophants, from bringingin the draconian 66A; from making it mandatory for people to stand up in cinema halls during the playing of the national anthem; from coming up with the aesthetically revolting idea of erecting world’s tallest flag-posts; from demanding an apology from the magazine that published the Danish cartoons – this from the Prime Minister of India, on the floor of the house; from staying silent when 8,000 activists were booked under the draconian sedition law by the Tamil Nadu police; from partaking in every possible chance our great democracy afforded to stifle free speech and expression; from ignoring every possible chance to repeal evil laws on sedition and free speech, the present government’s predecessors have been there, done that. The list of crimes and silences is endless. But Dhume doesn’t mention even a single intransigence. He fails to bemoan the fact that, far from providing liberties some breathing room, the Congress made things even more claustrophobic. Again, he is right in criticising the BJP, but he is wrong in giving his audience an impression that all this is happening for the first time, and that the BJP is responsible for it.

Dhume is not the first to have done this and he won’t be the last. In such a scenario, one may be entitled to ask: Are subjectivity and selectivity really all that harmful? Was Ambedkar wrong? What damage, after all, could selective outrage inflict on the reader and the running discourse?

Well, it can be devastating. Recall the early months of the Modi government and the media blitzkrieg over Church-attacks; the banner headlines screaming enough is enough, let Christians live in peace; the op-eds warning of creeping fascism and growing intolerance. What came of it? This, that three weeks of relentless boil and outrage later, the nation came to know that these attacks were nothing more than burglaries or accidents, that the perpetrators of the most heinous crime of sexual assault on a Bengal nun, one that quickly snowballedinto ‘Hindus are coming to get us, even the pious and the elderly won’t be spared’, were not Hindus; that as many churches were “attacked” under the UPA as they were under the present NDA.

We can outrage only on the news that we receive; and that which we don’t, it glides through the system unseen.

Under President Obama, during his first term in office, there occurred 1.1 million hate-crimes. 263,540 violent hate crimes were reported in 2012, just one year – 30 violent hate-crimes every hour. Of every day. 365 days. How many of these came to the reader’s notice? How many times was the Obama administration hauled over blazing coals for this? How many op-eds accused him of twiddling his thumbs while 30 minorities were attacked every hour of every day of every year?

Under Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, during his second term in office, there occurred 172,837 crimes against the Dalits. 2,073 rapes against Dalits were reported in 2013, just one year – a 31 per cent jump over the 2012 number. Five Dalit women were raped every single day in 2013.

The eye decides; the eye selects; the eye omits. Creeping fascism and growing intolerance become house lizards at will, scampering for cover under the shoe rack, leaving not even their writhing tails behind.

One may ask: why is it important to divulge previous occurrences – is that not Whataboutery? Why does a reader need to know that churches were also being “attacked” and robbed under the UPA, that 30 violent hate-crimes were happening every hour under Obama, that five Dalits were being sexually assaulted every day under Manmohan Singh? Why? Because outraging on any new occurrence with incomplete information is like fencing the adversary blind-folded; your every jab is in anger and desperation.

The solution to any problem is inextricably linked with its identification first as endemic or spontaneous. Rest is clickbait.

India is intolerant. Intolerant towards gays, towards Dalits, towards minorities (and majorities that become regional minorities), towards just and conscientious laws, towards free speech, towards freedom of expression. India has always been intolerant because we have laws, and Constitutional amendments, that protect Intolerance. The problem is endemic; it is not going to go away when the BJP goes away. But to realise this one has to forsake belief in one’s preferred ideology, preferred historians, preferred newspaper; preferred news channel; one has to forsake belief in selectivity. Easier said.

When it suits us, we become a nation of selective cacophony and silence.

The Left is silent when SFI goons go on a rampage; the Right is silent when ABVP goons indulge in the same. The Left is silent over one kind of bounty; the Right is silent over the other. The Left is silent when Muslims demand punishment for Kamlesh Tewari; The Right is silent when Hindus demand punishment for Prashant Bhushan. The Left is silent when a Muslim interprets Islam and his shop is burnt to the ground; the Right is silent when a film director interprets history and his set is burnt to the ground. The Left is silent when Yatra app is down-voted; the Right is silent when Snapdeal app is down-voted. The Left is silent when the communists rewrite our textbooks; the Right is silent when the nationalists rewrite our textbooks. The Left is silent when communists murder RSS workers; the Right is silent when RSS workers murder communists.

When it comes to selectivity, the Left and the Right are two sides of the same coin – emotional, impulsive, hypocritical, entrenched.

For the uninitiated, it takes some time to realise that this here is a game being played. The Great Indian Intolerance Chess Clock. Every single time there is intolerance that shames the Right, there follows intolerance that shames the Left. And vice versa. The Left outrages on one kind of intolerance, and the Right does the same for the opposite kind. The Left spots an atrocity that would shame the Right and slaps the intolerance chess clock; the Right spots an atrocity that would shame the Left and does the exact same after a while.

If I can shame you more than you can shame me, I believe that I can reduce my shame, disregard it even.

This constant jabbing at the other, while blind-folded, is what keeps the fire burning. Indian media discourse is this chalice runneth over with hundreds of stories that suit any one particular narrative. Take a sip, pass the cup along.

That selectivity can be immensely damaging to a nation's psyche is not quite apparent at first glance. This is because highlighting an atrocity devoid of its previous histories is in itself an important undertaking. To draw the reader's attention over any atrocity is essential in a democracy, to outrage over it equally so. No rational person can deny that even in isolation – i.e. devoid of previous history or knowledge an atrocity must be condemned and acted upon.

Why, then, did Ambedkar worry about selectivity? Why was he not satisfied with the selective outing of Hindu evils? It is because he was looking for solutions, and reforms – not just for one problem, not just for one community, but for the nation as a whole. He worried that conscientious Hindus shamed by their religion's evils would try and reform, but that conscientious Muslims not shamed by their religion's evils wouldn't. Reform is possible only when mistakes are identified, spoken of, written about, and the conscientious shamed. Shaming is good, shaming is essential, shaming is catharsis, but what good is shaming if it deepens further the chasms in our society, reforms only one community, is selective.

The writer Aatish Taseer has written an impassioned essay on the lynching of the Muslim Pehlu Khan at the hands of the Gau Rakshaks. It is an important read; it shames us as it should any conscientious Indian. Taseer talks of the murder of a Muslim at the hands of Hindu extremists; the outrage is real and affecting. At the end, Taseer holds India complicit in the murder: "...a whole nation, through its silence, is complicit," he writes.

If one has to hold the whole nation, including Taseer himself, complicit in the murder of a Muslim, why, then, would have asked Ambedkar, should that man not also be Farook, the Muslim lynched by Muslim extremists?

Farook, who, you ask. Farook, who, asks India. Farook, who, asks even Taseer.

Farook, a Muslim-turned-atheist, was lynched by Muslim extremists around the same time as Pehlu was by Hindu extremists. Pehlu is remembered, as he must be; but Farook is forgotten. Why? Why has Farook been forgotten? Is it because he was lynched by Muslims and not Hindus?

Who decides who is to be remembered and who forgotten? Who learns, who is shamed, who believes, who sees?

We do. Our selectivity does.

Holding India complicit for the murder of Pehlu will shame us into making sure such atrocities never happen again. But not holding India complicit for the murder of Farook, not shaming us for this atrocity, means that many more Farooks would meet the same fate. This, in summation, was what Ambedkar had warned us of.

But where is Objectivity; where do I find it?

Listen, Red. Far away there is an oak tree beneath whose tired, protruding roots is a biscuit tin containing a note that says, Don't just worship Ambedkar, follow him. Slither out that sewer pipe using your elbows and stand up on your legs and look up to face the heavens and let that rain wash away all the shit and the filth and give you the strength to find that tin. Find that tin, Red. It is your only hope.

You believe what you see, but unfortunately what you see is written by those who see what they believe.

A recent article by columnist Sadanand Dhume is proof if ever it was needed, that Objectivity is a metallic object that must be left behind before the writer passes through the op-ed threshold. All good now. Next!

Biases don’t beep.

The present article is not a rebuttal but, rather, an attempt to understand, using Dhume’s column, our fascination – both as writers and readers – with selectivity. To be sure, Dhume has written what needs to be read. He has highlighted the gross fraud perpetrated by the present Bharatiya Janata Party government, on freedom of speech, on the right to life, on the rule of law, and, to an exaggerated extent, on what all of us think India should be or become.

So where has he erred? To put it simply, here: Dhume has hidden more than he has revealed. He has indulged in selectivity, an attribute none other than BR Ambedkar warned us of 75 years ago. Explaining why selectivity is damaging, he wrote:

"The social evils which characterize the Hindu Society, have been well known. The publication of 'Mother India' by Miss Mayo gave these evils the widest publicity. But while 'Mother India' served the purpose of exposing the evils and calling their authors at the bar of the world to answer for their sins, it created the unfortunate impression throughout the world that while the Hindus were grovelling in the mud of these social evils and were conservative, the Muslims in India were free from them, and as compared to the Hindus, were a progressive people. That, such an impression should prevail, is surprising to those who know the Muslim Society in India at close quarters."

Ambedkar detested the evil orthodoxy of the Hindu society, exposed the casteist and bigoted nature of many ancient Hindu texts, spoke authoritatively on Hinduism, brought to light its numerous ills, left its fold to become a Buddhist; and yet, here was the same man warning us of being selective against Hinduism and Hindu society. Such was his greatness and unshakable belief to 'Do the Right Thing'.

It is astonishing how prescient, and relevant, Ambedkar’s words are even today; not at all astonishing that we discard them with the chirpy tediousness of a CISF body-frisker. Subjectivity brings us eyeballs; Objectivity brings us calm and rational thinking. Precisely the reason why hunched-over emotional beings hunting for fist-sized stones to pelt prefer the former.

Dhume writes with the immediacy of a columnist who understands, like all good columnists do, that his writings would the day after be used to wrap kachoris by the neighbourhood halwai. He is what one would call a modern writer – aware, alert, and receptive to criticism; a social media animal who tries to learn from his trolls and critics, knowing well the worth of this engagement as a self-correcting measure. A Twitter handle laden with followers bends.

Occasionally, though, Dhume gives in to a closed set of arty dunderheads who stand in the middle of summer braving scalding loo to admire the coming of age of a frangipani in a TV studio carpark. These would be the seers who think the world sucks on their analysis and interpretation like an emaciated leech. They drench the newspaper centrespreads and seal the primetime debates at will. Their word makes no sense but it is final. Subjectivity and selectivity are their calling cards. Dhume's last column suggests he was in their company.

Dhume claims personal liberties are shrinking under the present government, coming to this generalised conclusion from his wholly justified condemnation of the religious zealots who go by the moniker, Gau Rakshaks. These criminals are seemingly running amok, doubtless comforted by an overseeing government that is, outwardly at least, non-violently fanatical about saving cows. The almost complete lack of law enforcement resulting from fear of political masters, coupled with the cushion the overseers provide through their obsession with saving the Gau, is precisely the deadly combination the extremists cherish and take comfort in. This author had written previously on their barbarity and criminality. Many other have, too.

The Gau Rakshak menace is not a recent phenomena but one that is increasingly in the news. That said, an objective reading is the need of the hour, especially when it comes to sweeping psychoanalysis.

While Dhume rightly criticises the BJP and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh for zealously promoting the idea of a cow-slaughter ban, he should have mentioned that in doing so, these organisations are only following the ardent views of none other than Mahatma Gandhi and Vinobha Bhave, who incidentally went on a fast unto death unless his call for a pan-India cow slaughter ban was acceded to. Dhume should also have mentioned that the ban on cow slaughter was first implemented, and rigorously imposed in most Indian states, by the Congress party, so much so that as recently as 2015 Harish Rawat, a sitting Congress Chief Minister of Uttarakhand thundered. “Anyone who kills cows, no matter which community he belongs to is India's biggest enemy and has no right to live in the country.”

That is correct. India's biggest enemy. Not Pakistan or China but a cow-slaughterer.

The fools of the BJP are following the fools of the Congress, only more stridently because this is what fools do. To miss this facet of our daily political drudgery is to give the impression that things are happening for the first time, that the phrase déjà vu is Martian gobbledygook and not something invented by earthlings.

Dhume then talks of a deeper malaise, suggesting that under the present government, personal liberties are shrinking. Again, while Dhume rightly criticises the BJP for contributing to this, what undoubtedly is a malaise, he is silent on the fact that most of our personal liberties have been shrunk already, and to the extent they don't fit our bloated bodies anymore.