'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Monday, 12 December 2022

The Moral Governance of Others

In September, 22-year-old Mahsa Amini was admonished by the Guidance Patrol for ‘improperly’ wearing her hijab. She was then allegedly beaten to death. Her death triggered an unprecedented protest movement, in which women as well as men are attacking symbols of Iran’s theocracy like never before.

The protests have evolved into an open rebellion against Iran’s morality laws and against groups that the state has employed to implement these laws.

The Guidance Patrol is the successor of the Islamic Revolution Committees that were formed in 1979 to forcibly implement ‘Islamic morality’ in public spaces — especially when wearing the hijab was made compulsory in 1983. Over the years, there have been isolated protests against this law, but nothing like what Iran is witnessing today.

The protests are challenging the whole idea of ‘moral policing’ that began to be adopted by the state in many Muslim-majority countries from 1979 onwards. After Iran, moral policing units also emerged in Saudi Arabia and, from the 1990s, in Sudan, Afghanistan, Nigeria and, in certain regions of Malaysia and Indonesia.

The state gives the units powers to check and correct ‘moral digressions’, such as ‘inappropriate’ dressing (especially by women), ‘unseemly’ interaction between men and women in public, or the exhibition of any other ‘un-Islamic’ behaviour. Moral policing outfits have often been accused of using violent methods, mostly against women.

However, as morality policing organisations are now being openly challenged in Iran, recently they were disbanded in Saudi Arabia by the crown prince Muhammad bin Salman. Their presence contradicts his reformist agenda. Also, the criticism against the tactics used by the police was intensifying. Morality policing units were also dismantled in Sudan in 2019, after the overthrow of the dictator Omar al-Bashir.

According to Amanda F. Detrick (University of Washington, 2017): “States with religious systems of government, employ morality police as a formal method of social control to expand and stabilise their rule. Morality police units enable the regime to project power into society and retain dominance by affirming religious legitimacy, suppressing dissent and enforcing socio-religious and political uniformity.”

Moral policing can also emerge as an informal method of social control. According to the French philosopher Michel Foucault, the “governance of the self” can lead to the “governance of others.” In other words, sometimes, when an individual or a group embraces an idea of morality, they may end up enforcing this idea on others. If the enforcement finds traction among a large body of people in a society, the state is likely to adopt it as policy.

For example, even though most Muslim-majority countries do not have moral policing outfits formed by the state, ever since the 1980s, vigilante groups have been known to implement ‘morality’ by force. Such enforcements have often been turned into law by governments.

In Pakistan, for years, non-state groups campaigned to oust the Ahmadiyya from the fold of Islam. At first, the state treated the campaigns as subversive. But when the campaigns began to find greater traction among the polity, especially in the Punjab, the government declared the Ahmadiyya as a non-Muslim minority.

Informal methods of social control that emerge from below have been highly successful in Pakistan. From the late 1960s, there were campaigns against nightclubs, cinemas and the sale of alcoholic beverages by right-wing vigilante groups. They were suppressed by the government. But in the late 1970s, when a government was struggling to stall a political movement against it, it suddenly agreed to close down clubs and ban alcohol. But this was a futile attempt to regain social control.

Consequently, in 1980, there were plans by the Ziaul Haq dictatorship to form state-backed moral policing units. They were to enforce gender segregation in public spaces, ‘proper’ dressing habits (especially among women), compulsory prayers in the mosques, etc. Women’s organisations saw these as a way to strengthen a myopic patriarchal ethos. Their activism deterred the dictatorship from forming moral policing squads.

However, the frequency of vigilante groups enforcing (their ideas of) morality increased. For example, a group calling itself the ‘Allah Tigers’ started to raid hotels and even homes on every New Years Eve. Technically, their actions were unlawful, but the dictatorship tolerated them and saw them as the actions of ‘common people’ who were willingly implementing the state’s ‘Islamisation’ project.

There have also been non-state groups enforcing the hijab and discouraging the celebration of events such as Valentine’s Day. Although the government and the state have not appropriated these as policy, many educational institutions have.

But formal and informal methods of social control through moral policing are not only restricted to Muslim-majority countries. Ironically, outside the myths of ancient ‘pious’ states, one of the first formal examples in this respect appeared in 19th century England.

The regular police force in 19th century England was encouraged to ‘morally regulate’ the society. To 19th century British ‘gentry’, morality was deemed a necessary part of life, in order to hold and keep social stability. The police often took action (sometimes preemptive) against alleged prostitutes, drunkenness, betting and ‘habitual’ criminals.

Nevertheless, moral policing in most Muslim and, particularly in non-Muslim regions, has largely remained informal. But it has been rather successful in influencing state institutions. For example, years of anti-abortion activism in the US finally led to an abortion ban imposed by the US Supreme Court.

Also, in many countries, non-state moral policing of content on social media and the electronic media has pushed governments to pull down websites, films and TV shows. Interestingly, informal moral policing in a non-Muslim country has been most rampant in India. Vigilante groups often emerge to enforce ‘Hindu values’. These can include action against those celebrating Valentine’s Day, to lynching those who are accused of eating beef.

Moral policing is a serious issue. Morality has mostly to do with factors rooted in religion. There may be a consensus on the more general aspects of a faith, but there are always many interpretations of various topical aspects of it. One cannot impose morality based on a single interpretation.

Instead, states need to educate citizens to embrace pluralism and tolerance and exhibit behaviour that does not create social disruption and divisions. An individual’s choices that form their moral self-governance should be respected, as long as they are not raging to turn it into the governance of others.

Monday, 14 February 2022

‘Get into bed and see what happens’ – and nine other tips to revive a tired relationship

Nell Frizzell in The Guardian

At what point do you think a relationship becomes a long-term relationship?” I ask my boyfriend, while sitting on the toilet having a post-dinner wee. He is in front of the mirror, trimming the single thick black hair that grows out from a mole on his cheek. Our son is in the bath next to us, squirting water from one stainless steel mixing bowl into the other using a Calpol syringe.

“About here,” he says, gesturing towards the room, past my naked thighs, with a pair of nail scissors.

After nearly two years of intermittent lockdowns, working from home, reduced opportunities for travel, socialising and, in many cases, making money, and more illness, a lot of long-term relationships are looking a little tired, a little frayed. Tempers have run short; desire has faded. Especially on this most “romantic” of days, many us will be thinking that we need to address things. To freshen up. To repair. This calls for more than a box of chocolates and a bunch of flowers.

But where to start? I’ve been gleaning advice from those who have gone before me – from friends, relationship counsellors, old colleagues, writers and philosophers, even my family.

Photograph: 10’000 Hours/Getty Images

Lower your expectations

Your partner is not psychic: they cannot know what you think and feel and want at every turn. Nor is your partner an extension of you: they will frequently and unconsciously contradict you. So lower your expectations and try, as much as possible, to be kind. Standing at the hob, cooking yet another vat of soup (my partner and I have both decided that we need to eat fewer meals centred on butter and flour), I re-read Alain de Botton’s famous New Yorker essay Why You Will Marry the Wrong Person: “We need to swap the Romantic view for a tragic (and at points comedic) awareness that every human will frustrate, anger, annoy, madden and disappoint us – and we will (without any malice) do the same to them. There can be no end to our sense of emptiness and incompleteness. But none of this is unusual or grounds for divorce. Choosing whom to commit ourselves to is merely a case of identifying which particular variety of suffering we would most like to sacrifice ourselves for.” I add some salt. And a knob of butter. Well, come on…

Mind your language

My sister’s dad (who, for the genealogists in the room, is not my dad) once told me that people don’t break up over big things; they break up over how they talk to each other. Yes, in the end, your partner might sleep with someone else or steal your rent. But in most cases, the damage is done when you stop saying goodbye at the end of phone calls, stop saying thank you for dinner, stop asking the other person how their day was.

However, blaming someone else’s behaviour is unlikely to change it. “People could really do with saying what they need, not what they think the other partner should do,” says Relate counsellor Josh Smith, who has been working with couples and families for more than five years. “Also, set a time and space when you’re going to talk about things but give it a time limit. A person who is feeling anxious might want to talk about an issue, but their partner might be more inclined to avoid difficult conversations and worried it will go on for ever. So you could say: ‘Let’s talk for half an hour and then stop.’” Smith also recommends giving yourself a timeout during those exhausting, essential conversations. “When our nervous system gets very aroused, we might say things we don’t mean, or not be able to say very much at all and disconnect emotionally. Being able to take a timeout, with a planned time to return to [the discussion], will help you listen.”

Go to counselling while you still like each other

When you hear counsellors talk about their clients, says Smith, the one thing that comes up time and time again is that they wish they’d come sooner – before the fight-or-flight response got so ingrained and the conflict so advanced that partners could no longer hear each other. So, to use a rather threadbare analogy, maybe treat relationship counselling like going to the gym: something that you use regularly to keep things healthy, to nip small problems in the bud, rather than turn to when things have seriously gone to seed. It is a privilege that many people can’t afford, of course, but it might also be money well spent.

Get into bed and see what happens

Sex is a pretty fundamental (and free) way to cement intimacy in a relationship. It can also act as a microcosm for the relationship: when people are feeling stressed, anxious, avoidant, low in self-esteem, bored or overlooked, it will almost inevitably lead to a drop-off in bouncing bedsprings. “For most of the couples I see, sex is an issue,” says Smith. “It’s not unusual for people in long-term relationships to have very little sex.” Well, who’d have guessed? “But that’s not a problem if it’s not a problem,” he adds. “Don’t let normative ideas about sex get in the way.”

That doesn’t mean you have to give up just yet. When I asked my family WhatsApp group how to reboot a long-term relationship, one cousin replied: “Actively listen, be nice to each other and have sex even in times you might not feel like it (and then remember how much you do actually like it).”

Flirt with other people

If you still need a little boost, remember what the psychotherapist Esther Perel says about desire in her Ted Talk, The Secret to Desire in a Long-Term Relationship: “If there is a verb, for me, that comes with love, it’s ‘to have’. And if there is a verb that comes with desire, it is ‘to want’.” The journalist Katie Antoniou puts it like this: “Go to a party and watch your partner flirt with other people and remember why you find them hot. And flirt with other people and remember people find you hot. Then go home together.”

Do at least one thing separately every day

One of the great challenges in a long-term relationship is judging how much time to actually spend together. “During the pandemic, I noticed that people’s lives became a bit enmeshed,” says Smith, in possibly the greatest understatement of 2022. “Having different experiences and being able to bring those back into the relationship can be really healthy.”

As Perel points out: “We come to one person, and we are basically asking them to give us what once an entire village used to provide.” We want security, companionship, perhaps children, a best friend, a trusted confidante, a red-hot lover and someone to help us fulfil our daily domestic tasks. This is, probably, an unfair expectation of any single person. Put too many eggs in the long-term partner basket and cracks are going to show, if not yolk and leaking albumen. So don’t be afraid to look outside your relationship for other connections. It is not a criticism of your romantic relationship to go on holiday, share childcare, work, go to dinner, play football and watch films with other people. And, whether it’s a hobby, a shed or a separate bed, don’t be afraid to carve out a private sphere within your relationship. My greatest – and possibly only – bit of advice about sustaining a long-term relationship is to share a bed but have two separate duvets. The Germans, as is so often the case, have the answer.

Feel the fear …

“Long-term relationships aren’t like warm baths; they’re like holding a tiger by the tail.” I’m on the phone to a friend who has been in his current relationship – I say “current” because, honestly, who am I to say? – for a mere 43 years. When it comes to relationship advice, as he admits, his understanding of dating, casual sex, breakups and asking people out is minimal. “She moved in when I was 19 and that was it, really.” But he is rather useful on the long-term front. “There are two main approaches, as I see it,” he says. “There is the passive state, which some people can find very sustaining, when it would basically be such a faff to split up that you’re staying together.” I think of my mortgage and our son and the fact that I still cannot replace my brake pads. “Or there is the active approach, where you’re always opting in. That’s what I chose.”

The reason he and his partner didn’t marry for the first 42 years of their relationship, he says, is that they always wanted to know that they were together because they were choosing to be so. “I quite liked the jeopardy,” he says. “It’s a constant dialogue between exhilaration and exhaustion. At any time, I could have walked away. We had made no promise; there was no contract. Which meant that, every day, I knew I was there because I wanted to be there.”

But what about the days when you don’t want to be there, I ask, picking a used teabag off the lid of the compost bin and putting it into the compost bin. “Well, that’s when the exhaustion comes in,” he says. “And you have to have those conversations about where you are and what you want.”

… but don’t be afraid of all change

A priest once told me that, over a lifetime, you will be married several times – and if you’re lucky, that will be to the same person. Children, work, where you live, money, health: the things that change your life will change your relationship too. So do the work to make those changes happen with, and in parallel to, your partner. Talk to each other about the ways you are developing and how you can adapt the dimensions and texture of your relationship to fit. Few of us would really want to be the person we were 10 years ago (in my case: single, recently redundant and staying in my mum’s spare room), so don’t expect your partner or your relationship to be held in aspic either.

It is also worth pointing out that the things that bring you stress outside your relationship – money worries, illness, unemployment, housing insecurity, the demands of parenting, grief and moving home – will create stress within your relationship. So check if there are things you can do to improve your own situation before blaming your partner.

Make time for quality time (even if you hate the phrase)

Date nights worked for the Obamas, who once famously flew to New York, took a limo to dinner, watched a Broadway show and then flew home all in one night, during his presidency. And it was noticeable to me that the first time my partner and I spent a night away together since our son was born four years ago, we ended up not only sleeping in a bedroom covered in photographs of someone else’s whippets, but getting engaged. It doesn’t have to involve money, travel or Instagram. Time spent together away from your usual domestic coexistence – even if it’s just a swim, or a train journey, or a trip to a new launderette – can make a huge difference to how you see your partner.

Remember the little joys

Finally, having picked up my partner’s socks from the floor, made the bed, rehung the damp, onion-smelling towel he had flung in a heap over the door, and wiped the peanut butter off my forehead, I asked my old English teacher for his advice. This, after all, is the man who taught Philip Larkin’s An Arundel Tomb, with its description of the stone earl and his lady countess, who rigidly persisted, “linked, through lengths and breadths of time”. More to the point, he’s been with his partner since they met at a party aged 20, more than 40 years ago. He must, I reasoned, have some ideas about what sustains and revives a long-term relationship.

The reply comes back mere minutes later: “Amnesia, dogged optimism, a robust and shared sense of the contemptibility of public figures, alternating phases of heartfelt loyalty and shameless disloyalty with regard to friends and birth families, lonesome sheds with tools in them, compatible levels of existential angst, sunsets, recreational stimulants, utterly selfish projects, wholly unshared obsessions, a poor sense of smell, frequently sleeping in separate beds, frequently sleeping together, children, finding each other ridiculous, plant life, lakes, oceans, rock pooling, books, solvency, knowing who’s better at what, dreaming of elsewhere, avoiding all board games and exercising dictatorial authority over territories in different areas of daily mundanities.” His wife, he later tells me, probably had a better list. I would happily marry either of them.

Oh, and one final note: in all my research, nobody mentioned shutting the door when you’re on the toilet. But I’d say give it a try.

Wednesday, 28 July 2021

Monday, 11 February 2019

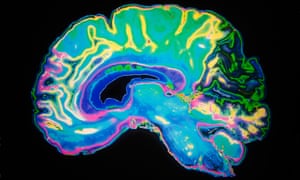

What is love – and is it all in the mind?

What do you get when you fall in love?

We crave romantic love like nothing else, we’ll make unimaginable sacrifices for it and it can take us from a state of ecstasy to deepest despair. But what’s going on inside our heads when we fall in love?

The American anthropologist Helen Fisher describes the obsessive attachment we experience in love as “someone camping out in your head”.

In a groundbreaking experiment, Fisher and colleagues at Stony Brook University in New York state put 37 people who were madly in love into an MRI scanner. Their work showed that romantic love causes a surge of activity in brain areas that are rich in dopamine, the brain’s feelgood chemical. These included the caudate nucleus, part of the reward system, and an ancient brain area called the ventral tegmental area, or VTA. “[The VTA] is part of the reptilian core of the brain, associated with wanting, motivation, focus and craving,” Fisher said in a 2014 talk on the subject. Similar brain areas light up during the rush of euphoria after taking cocaine.

MRI scans of the brains of those in love found surges of activity of dopamine. Photograph: Daisy-Daisy/Alamy

During the early stages of love, the emotional excitement (or some might say stress) raises the body’s cortisol levels, causing a racing heart, butterflies in our stomach and inconveniently sweaty palms. Other chemicals in play are oxytocin, which deepens feelings of attachment, and vasopressin, which has been linked to trust, empathy and sexual monogamy.

So it’s a total eclipse of the head, not the heart?

Actually … in a case of science imitating poetry, the heart has been found to influence the way we experience emotion.

Our brain and heart are known to be in close communication. When faced with a threat or when we spot the object of our affection in a crowded room, our heart races. But recently, scientists have turned the tables and shown that feedback from our heart to our brain also influences what we are feeling.

What the heart is doing can influence how strongly our brain processes emotion. Photograph: Borja Suarez/Reuters

One study, led by Prof Sarah Garfinkel of the University of Sussex, showed that cardiovascular arousal – the bit of the heart’s cycle when it is working hardest – can intensify feelings of fear and anxiety. In this study, people were asked to identify scary or neutral images while their heartbeats were tracked. Garfinkel found they reacted quicker to the scary images when their heart was contracting and pumping blood, compared with when it was relaxing. Her work suggests that electrical signals from blood vessels around the heart feed back into brain areas involved in emotional processing, influencing how strongly we think we’re feeling something.

Finally, in what must be a contender for one of the most romantic (or mushy) scientific insights to date, couples have been shown to have a tendency to synchronise heartbeats and breathing.

Why is it a crazy little thing?

Love is merely a madness, Shakespeare wrote. But it is only recently that scientists have offered an explanation for why being in love might inspire unusual behaviour.

Donatella Marazziti, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Pisa, approached this question after carrying out research showing that people with obsessive compulsive disorder have, on average, lower levels of the brain chemical serotonin in their blood. She wondered whether a similar imbalance could underlie romantic infatuation.

She recruited people with OCD, healthy controls and 20 people who had embarked on a romantic relationship within the previous six months (it was also specified that they should not have had sexual intercourse and that at least four hours a day were spent thinking of the partner). Both the OCD group and the volunteers who were in love had significantly lower levels of serotonin, and the authors concluded “that being in love literally induces a state which is not normal”. When the “in love” group were followed up six months later, most of their serotonin levels had returned to normal.

A separate study found that people in love have much lower activity in their frontal cortex – an area of the brain crucial to reason and judgment – when they thought of their loved one. Scientists have speculated an evolutionary reason for this which could be termed the “beer goggles” theory: the suspension of reason makes coupling, and hence procreation, far more likely.

So all in love is fair – regardless of sexual orientation?

Sexual orientation has several components, including behaviour, identity, attraction and arousal.

Many scientific studies have been based on who people say they are attracted to, and surveys typically find that same-sex attraction accounts for fewer than 5% of the population, and this figure has remained relatively stable over time. But people’s behaviour and the labels they use to describe their sexual identity appear to be influenced to a greater degree by social and cultural factors.

For instance, in the UK there has been a sharp rise in the proportion of women reporting having had a sexual experience with another woman, from 1.8% in 1991 to 7.9% in 2013, according to the National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles, which is carried out each decade.

As with any scientific investigation, the way questions are framed also makes a difference to the answer. So studies that ask people to pick between two or three categories would miss any more subtle gradations. As Kinsey wrote in 1948: “The living world is a continuum in each and every one of its aspects. The sooner we learn this concerning human sexual behaviour, the sooner we shall reach a sound understanding of the realities of sex.”

Women are considerably more likely than men to rate themselves on a continuum of sexuality, Photograph: Sam Edwards/Getty Images/Caiaimage

There is growing support for the idea of a continuum, in particular for women who are considerably more likely than men to rate themselves as intermediate categories such as “mostly heterosexual” (10% v 4%), when given those options.

It’s worth noting that a 2011 study found no differences between brain systems regulating romantic love in homosexuals and heterosexuals.

Is there a gay gene?

It has been known for decades that sexual orientation is partly heritable in men, based on studies of identical and fraternal twins. In the 1990s, a specific region of the X chromosome was linked to male homosexuality and more recent two specific genes have been found to be more common in gay men.

However, the genetic factors that have been identified so far only play a small part in determining sexuality – not all men who have these genes are gay. Research on the genetic basis of female sexuality lags behind, which some have attributed to it being more difficult to study. Others might conclude that there has simply been less effort to understand this topic.

There are other biological factors at play as well. One of the most robust findings in sexual-orientation research is the fraternal-birth-order effect: gay men tend to have a greater number of older brothers compared with straight men. This is a biological influence rather than a social one and is a big effect, increasing the odds of a man being gay by roughly a third. In women, there is evidence that pre-natal hormone exposure can make a difference to sexual orientation.

Let’s get chemical: do humans give off pheromones?

Pheromones are chemical signals that are used to communicate and alter the behaviour of others. The first pheromone discovered, in the 1950s, was a substance called bombykol that female silkworms emit to attract males. Ever since then, the search has been on – not least by perfume manufacturers – to find a human equivalent. There have been some tentative claims.

A pheromone present in male pigs, androstenone, has also been found in the human armpit. Photograph: Joe Pepler/Rex Features

For instance, a known pig pheromone, androstenone, has been found in the human armpit. When female pigs on heat get a whiff of the substance, which is found in boars’ saliva, they adopt the mating stance. However, there is not yet any convincing evidence for real-life “Lynx effect” chemicals in men and women. The strongest contender to date for a human pheromone is a chemical secreted from glands in the nipples of breastfeeding mothers. When wafted under any sleeping baby’s nose, the child responds with sucking and rooting behaviour.

Your cheating heart – how uncommon is it?

Cheating is widely disapproved of, but is not that uncommon. According to the University of Chicago’s General Social Survey, men are on average more likely than women to be unfaithful – 20% of men and 13% of women reported that they’ve had sex with someone else while married.

However, the figures shifted across age ranges, with women in the youngest age range (18-29) being marginally more likely (11% v 10%) to have cheated, with the widest gender gap in the 80+ range where 24% of men and just 6% of women said they had been unfaithful.

Recently scientists have shown that some people may be genetically predisposed to being unfaithful. One study of nearly 7,400 Finnish twins and their siblings found a significant link between the vasopressin gene and infidelity in women.

Another study, by scientists at the Kinsey Institute, in Indiana, showed that certain variants of the gene for the dopamine receptor were more likely to be unfaithful and also more likely to be repeatedly unfaithful.