'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label poetry. Show all posts

Showing posts with label poetry. Show all posts

Monday, 11 June 2018

Wednesday, 30 March 2016

Poetry or property punts: what's driving China's love affair with Cambridge?

David Cox in The Guardian

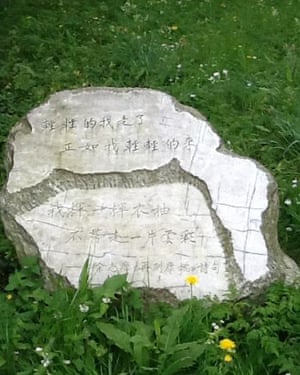

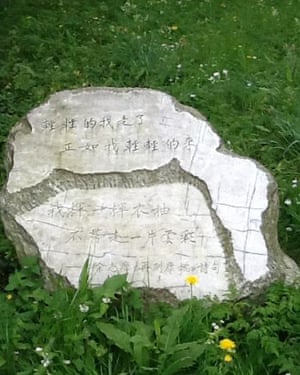

On the edge of Scholar’s Piece, the strip of farmland just behind King’s College, lies a granite stone which has become arguably Cambridge’s most coveted tourist attraction.

For the many students who amble past it every day, it’s easily missed; placed rather innocuously next to the bridge that joins Scholar’s Piece to the rest of the college. But for the thousands of Chinese tourists who travel to Cambridge every year, it is this, rather than the city’s grand 15th-century chapel, meticulously manicured lawns or historical statues, that they’ve come to see.

Carved into the stone are the first and last lines of a poem that has gone down in Chinese folklore. Titled Farewell to Cambridge, it was written in 1928 by Xu Zhimo, a 31-year-old poet and writer who was revisiting King’s after studying there in the early 20s.

Zhimo died three years later in a plane crash, but he would go down as a cult figure in modern Chinese history, immortalised through his premature and tragic end, illicit love affairs and success in introducing western forms into Chinese literature.

Looking to invest? … Tourists enjoy a punt tour along the river. Photograph: Chris Radburn/PA

“There is undoubtedly interest in Cambridge as a place to live from Chinese buyers,” says Ed Meyer, head of residential at Savills Cambridge. “But as well as an investment, the major driver for this is education. The majority of Chinese buyers are coming here with younger children, to try and integrate them into Cambridge society and the schools round here, with the view that they will hopefully go to the university in future. And Xu Zhimo’s legacy definitely seems to be ingrained in their psyche. At some point they always explain, ‘Oh, and we know about Cambridge because we learnt about it in the poem at school.’”

Cambridge’s academic reputation is instilled into virtually all Chinese children at a young age. While domestic universities such as Peking and Tsinghua are respected, those who can afford it are increasingly opting to put their money into sending their children abroad for schooling, with the hope of gaining them an edge in a hyper-competitive job market when they return home. Such are the employability benefits associated with a Cambridge education that increasing numbers are sending their children to the various “feeder schools” around the city to boost their chances of a successful application.

On the edge of Scholar’s Piece, the strip of farmland just behind King’s College, lies a granite stone which has become arguably Cambridge’s most coveted tourist attraction.

For the many students who amble past it every day, it’s easily missed; placed rather innocuously next to the bridge that joins Scholar’s Piece to the rest of the college. But for the thousands of Chinese tourists who travel to Cambridge every year, it is this, rather than the city’s grand 15th-century chapel, meticulously manicured lawns or historical statues, that they’ve come to see.

Carved into the stone are the first and last lines of a poem that has gone down in Chinese folklore. Titled Farewell to Cambridge, it was written in 1928 by Xu Zhimo, a 31-year-old poet and writer who was revisiting King’s after studying there in the early 20s.

Zhimo died three years later in a plane crash, but he would go down as a cult figure in modern Chinese history, immortalised through his premature and tragic end, illicit love affairs and success in introducing western forms into Chinese literature.

The ‘Farewell to Cambridge’ stone. Photograph:Historyworks/Flickr

And while Zhimo spent most of his life in China, Farewell to Cambridge has become his legacy. It is now part of China’s national curriculum, taught to all schoolchildren as an example of the modern poetry movement in the early 20th century.

“The poem is something we’ve all heard of,” says Pei-Ling Lau from Beijing, who is visiting King’s and seeing Zhimo’s stone for the first time. She studied his poem as a compulsory exam text when she was 15: “It’s been adapted into many pop songs too. It paints such a lovely picture of punting in Cambridge, but it wasn’t until I came here that I realised how beautifully it describes the river. It’s special for Chinese people as the life and story of Xu Zhimo is well known, and this was his city. We want to come here and experience that.”

And come they do. Numbers of Chinese tourists visiting the UK have soared in recent years from 115,000 in 2009 to 336,000 in 2014, following the relaxation ofvisa restrictions to Chinese nationals in 2013. With further amendments in the pipeline to boost this lucrative tourist trade, these figures are only set to increase.

But the Chinese are not just interested in Cambridge as a holiday location; they also view it as a key region for property investment. Cambridge’s house prices are soaring, with new figures revealing they have increased by 50% since 2010, driven in large part by the ongoing biotech boom in science parks around the city. And wealthy Chinese appear keen to cash in: the estate agents Savills estimate that in the past year, one in 20 new-build homes across the city and surrounding villages have been bought by Chinese owners.

And while Zhimo spent most of his life in China, Farewell to Cambridge has become his legacy. It is now part of China’s national curriculum, taught to all schoolchildren as an example of the modern poetry movement in the early 20th century.

“The poem is something we’ve all heard of,” says Pei-Ling Lau from Beijing, who is visiting King’s and seeing Zhimo’s stone for the first time. She studied his poem as a compulsory exam text when she was 15: “It’s been adapted into many pop songs too. It paints such a lovely picture of punting in Cambridge, but it wasn’t until I came here that I realised how beautifully it describes the river. It’s special for Chinese people as the life and story of Xu Zhimo is well known, and this was his city. We want to come here and experience that.”

And come they do. Numbers of Chinese tourists visiting the UK have soared in recent years from 115,000 in 2009 to 336,000 in 2014, following the relaxation ofvisa restrictions to Chinese nationals in 2013. With further amendments in the pipeline to boost this lucrative tourist trade, these figures are only set to increase.

But the Chinese are not just interested in Cambridge as a holiday location; they also view it as a key region for property investment. Cambridge’s house prices are soaring, with new figures revealing they have increased by 50% since 2010, driven in large part by the ongoing biotech boom in science parks around the city. And wealthy Chinese appear keen to cash in: the estate agents Savills estimate that in the past year, one in 20 new-build homes across the city and surrounding villages have been bought by Chinese owners.

Looking to invest? … Tourists enjoy a punt tour along the river. Photograph: Chris Radburn/PA

“There is undoubtedly interest in Cambridge as a place to live from Chinese buyers,” says Ed Meyer, head of residential at Savills Cambridge. “But as well as an investment, the major driver for this is education. The majority of Chinese buyers are coming here with younger children, to try and integrate them into Cambridge society and the schools round here, with the view that they will hopefully go to the university in future. And Xu Zhimo’s legacy definitely seems to be ingrained in their psyche. At some point they always explain, ‘Oh, and we know about Cambridge because we learnt about it in the poem at school.’”

Cambridge’s academic reputation is instilled into virtually all Chinese children at a young age. While domestic universities such as Peking and Tsinghua are respected, those who can afford it are increasingly opting to put their money into sending their children abroad for schooling, with the hope of gaining them an edge in a hyper-competitive job market when they return home. Such are the employability benefits associated with a Cambridge education that increasing numbers are sending their children to the various “feeder schools” around the city to boost their chances of a successful application.

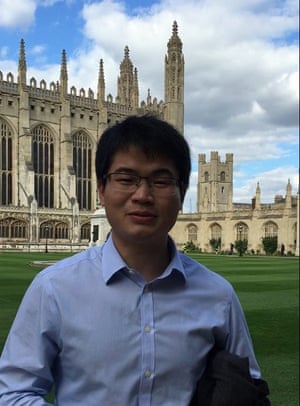

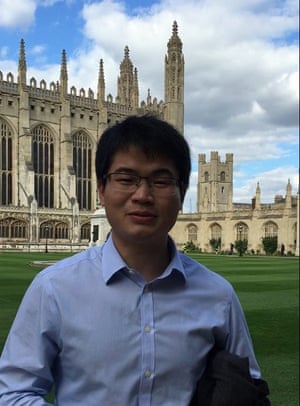

Cambridge PhD student Zongyin Yang. Photograph: David Cox

“The reputations of the great universities are passed down from parents to children,” says Zongyin Yang, a PhD student at Cambridge who grew up in Wenzhou. “There’s a respect and curiosity which is instilled at a young age. It’s why Chinese families bring their toddlers to see the campuses. Most children grow up hearing about these ‘dream places’.”

According to China’s Ministry of Education, 459,800 students enrolled at overseas universities in 2014, an increase of 11.1% on the previous year. Of these, 423,000 were entirely funded by their families. And at the top of their list is Cambridge: Chinese students make up the largest ethnic population at the university, with a total of around 900 enrolled for the current academic year.

“A Cambridge degree is definitely perceived to be superior in the recruitment process due to the strength of the brand name,” says Zheng Yao, who studied at Cambridge before returning to Beijing. “There’s a widespread perception that your earning potential in China will be much greater – but the reality is quite different. Pay for new graduates is in fact very limited, no matter where you’ve studied.”

Volatile market

Buying property in Cambridge also makes financial sense for Chinese families looking to invest their money outside of the increasingly volatile market back home. “Chinese parents would rather their children pay rent to them than to another landowner, keeping the money in the family,” explains Keri Wong, a Cambridge student from Guangzhou. “And while the Chinese middle classes have a lot of savings, the market at home is regarded as really unstable. UK property is an attractive divestment. Plus property investment presents the option of being able to eventually gain UK residency status.”

We don’t want our housing market going through a boom-or-bust cycle based on the Chinese economyDuncan Stott

But not everyone is welcoming the new residents. “At some point the world economy will shift and overseas investors will decide that they’re better placing their money elsewhere,” says Duncan Stott, of the local campaign groupPricedOut. “But we don’t want our housing market going through a boom-or-bust cycle based on the Chinese economy. We need a more stable housing market so prices aren’t going to be going up faster than people can earn, before plunging and dropping people into negative equity.”

Stott and many others are especially unhappy about the trend of overseas buyers purchasing homes entirely for investment purposes and leaving them empty for several years, before selling them at a profit. While council taxes are raised on empty properties, the inflation in their price means this does not prove a deterrent. Kevin Price, Cambridge’s executive councillor for housing, says there are currently 240 homes in the city sitting empty.

Is it fair to blame this on the interest from China in particular? “Houses are a safe, strong investment which appeals to people both overseas and those already living here,” says David Bentley, of estate agent Bidwells. “Cambridge is a global brand, so it’s not just the Chinese looking to invest here. We’ve seen a big influx of Russian money too. And the Chinese are typically buying not just as an investment, but for their children, sometimes even before they’ve reached school age.”

“The reputations of the great universities are passed down from parents to children,” says Zongyin Yang, a PhD student at Cambridge who grew up in Wenzhou. “There’s a respect and curiosity which is instilled at a young age. It’s why Chinese families bring their toddlers to see the campuses. Most children grow up hearing about these ‘dream places’.”

According to China’s Ministry of Education, 459,800 students enrolled at overseas universities in 2014, an increase of 11.1% on the previous year. Of these, 423,000 were entirely funded by their families. And at the top of their list is Cambridge: Chinese students make up the largest ethnic population at the university, with a total of around 900 enrolled for the current academic year.

“A Cambridge degree is definitely perceived to be superior in the recruitment process due to the strength of the brand name,” says Zheng Yao, who studied at Cambridge before returning to Beijing. “There’s a widespread perception that your earning potential in China will be much greater – but the reality is quite different. Pay for new graduates is in fact very limited, no matter where you’ve studied.”

Volatile market

Buying property in Cambridge also makes financial sense for Chinese families looking to invest their money outside of the increasingly volatile market back home. “Chinese parents would rather their children pay rent to them than to another landowner, keeping the money in the family,” explains Keri Wong, a Cambridge student from Guangzhou. “And while the Chinese middle classes have a lot of savings, the market at home is regarded as really unstable. UK property is an attractive divestment. Plus property investment presents the option of being able to eventually gain UK residency status.”

We don’t want our housing market going through a boom-or-bust cycle based on the Chinese economyDuncan Stott

But not everyone is welcoming the new residents. “At some point the world economy will shift and overseas investors will decide that they’re better placing their money elsewhere,” says Duncan Stott, of the local campaign groupPricedOut. “But we don’t want our housing market going through a boom-or-bust cycle based on the Chinese economy. We need a more stable housing market so prices aren’t going to be going up faster than people can earn, before plunging and dropping people into negative equity.”

Stott and many others are especially unhappy about the trend of overseas buyers purchasing homes entirely for investment purposes and leaving them empty for several years, before selling them at a profit. While council taxes are raised on empty properties, the inflation in their price means this does not prove a deterrent. Kevin Price, Cambridge’s executive councillor for housing, says there are currently 240 homes in the city sitting empty.

Is it fair to blame this on the interest from China in particular? “Houses are a safe, strong investment which appeals to people both overseas and those already living here,” says David Bentley, of estate agent Bidwells. “Cambridge is a global brand, so it’s not just the Chinese looking to invest here. We’ve seen a big influx of Russian money too. And the Chinese are typically buying not just as an investment, but for their children, sometimes even before they’ve reached school age.”

The link between Cambridge and China goes back to the 19th century, when the university reformed itself based on the Chinese imperial examination system, before launching the UK’s first professorship of Chinese in 1888.

Two centuries on, the link only looks set to strengthen. With the Home Office launching a new visa system that allowsChinese tourists to make multiple visits over a two-year period, and school and university applications rising every year, the distinct Chinese presence in the city is surely only going to grow.

And for local residents already worried that Cambridge’s housing supply isn’t keeping up with demand, the potential impact of such interest remains a concern – even if, as Bentley points out, the percentage of purchases from overseas buyers is still relatively small.

“It’s a difficult problem to do anything about, but having such strong interest from Chinese buyers just puts even more pressure on an already strained housing market,” Stott adds. “It simply makes it more and more difficult for people who already live here to be able to own their own homes.”

Two centuries on, the link only looks set to strengthen. With the Home Office launching a new visa system that allowsChinese tourists to make multiple visits over a two-year period, and school and university applications rising every year, the distinct Chinese presence in the city is surely only going to grow.

And for local residents already worried that Cambridge’s housing supply isn’t keeping up with demand, the potential impact of such interest remains a concern – even if, as Bentley points out, the percentage of purchases from overseas buyers is still relatively small.

“It’s a difficult problem to do anything about, but having such strong interest from Chinese buyers just puts even more pressure on an already strained housing market,” Stott adds. “It simply makes it more and more difficult for people who already live here to be able to own their own homes.”

Sunday, 3 February 2013

Like poetry for software - Open Source

T+

Open source programme creators cater to the highest standards and give away their work for free, much like Ghalib who wrote not just for money but the discerning reader

Mirza Ghalib, the great poet of 19th century Delhi and one of the greatest poets in history, would have liked the idea of Open Source software. A couplet Mirza Ghalib wrote is indicative:

Bik jaate hain hum aap mata i sukhan ke saath

Lekin ayar i taba i kharidar dekh kar

(translated by Ralph Russell as:

I give my poetry away, and give myself along with it

But first I look for people who can value what I give).

Free versus proprietary

Ghalib’s sentiment of writing and giving away his verses reflects that of the Free and Open Source software (FOSS) movement, where thousands of programmers and volunteers write, edit, test and document software, which they then put out on the Internet for the whole world to use freely. FOSS software now dominates computing around the world. Most software now being used to run computing devices of different types — computers, servers, phones, chips in cameras or in cars, etc. — is either FOSS or created with FOSS. Software commonly sold in the market is referred to as proprietary software, in opposition to free and open source software, as it has restrictive licences that prohibit the user from seeing the source code and also distribute it freely. For instance, the Windows software sold by Microsoft corporation is proprietary in nature. The debate of FOSS versus proprietary software (dealing with issues such as which type is better, which is more secure, etc.) is by now quite old, and is not the argument of this article. What is important is that FOSS now constitutes a significant and dominant part of the entire software landscape.

The question many economists and others have pondered, and there are many special issues of academic journals dedicated to this question, is why software programmers and professionals, at the peak of their skills, write such high quality software and just give it away. They spend many hours working on very difficult and challenging problems, and when they find a solution, they eagerly distribute it freely over the Internet. Answers to why they do this range, broadly, in the vicinity of ascribing utility or material benefit that the programmers gain from this activity. Though these answers have been justified quite rigorously, they do not seem to address the core issue of free and open source software.

I find that the culture of poetry that thrived in the cultural renaissance of Delhi, at the time of Bahadur Shah Zafar, resembles the ethos of the open source movement and helps to answer why people write such excellent software, or poetry, and just give it away. Ghalib and his contemporaries strived to express sentiments, ideas and thoughts through perfect phrases. The placing of phrases and words within a couplet had to be exact, through a standard that was time-honoured and accepted. For example, the Urdu phrase ab thhe could express an entirely different meaning, when used in a context, from the phrase thhe ab, although, to an untrained ear they would appear the same. (Of course, poets in any era and writing in any language, also strove for the same perfection.)

Ghalib wrote his poetry for the discerning reader. His Persian poetry and prose is painstakingly created, has meticulous form and is written to the highest standards of those times. Though Ghalib did not have much respect for Urdu, the language of the population of Delhi, his Urdu ghazals too share the precision in language and form characteristic of his style. FOSS programmers also create software for the discerning user, of a very high quality, written in a style that caters to the highest standards of the profession. Since the source code of FOSS is readily available, unlike that for proprietary software, it is severely scrutinised by peers, and there is a redoubled effort on the part of the authors to create the highest quality.

Source material

Ghalib’s poetry, particularly his ghazals, have become the source materials for many others to base their own poetry. For example, Ghalib’s couplet Jii dhoondhta hai phir wohi ... (which is part of a ghazal) was adapted by Gulzar as Dil dhoondhta hai phir wohi..., with many additional couplets, as a beautiful song in the film Mausam. It was quite common in the days of the Emperor to announce azameen, a common metre and rhyming structure, that would then be used by many poets to compose their ghazals and orate them at a mushaira (public recitation of poetry). FOSS creators invariably extend and build upon FOSS that is already available. The legendary Richard Stallman, who founded the Free software movement, created a set of software tools and utilities that formed the basis of the revolution to follow. Millions of lines of code have been written based on this first set of free tools, they formed the zameen for what was to follow. Many programmers often fork a particular software, as Gulzar did with the couplet, and create new and innovative features. (Editor's note - Newton stated the same principle on his discoveries when he said, "If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants".)

Ghalib freely reviewed and critiqued poetry written by his friends and acquaintances. He sought review and criticism for his own work, although, it must be said, he granted few to be his equal in this art (much like the best FOSS programmers!). He was meticulous in providing reviews to his shagirds(apprentices) and tried to respond to them in two days, in which time he would carefully read everything and mark corrections on the paper. He sometimes complained about not having enough space on the page to mark his annotations. The FOSS software movement too has a strong culture of peer review and evaluation. Source code is reviewed and tested, and programmers make it a point to test and comment on code sent to them. Free software sites, such as Sourceforge.org, have elaborate mechanisms to help reviewers provide feedback, make bug reports and request features. The community thrives on timely and efficient reviews, and frequent releases of code.

Ghalib was an aristocrat who was brought up in the culture of poetry and music. He wrote poetry as it was his passion, and he wanted to create perfect form and structure, better than anyone had done before him. He did not directly write for money or compensation (and, in fact, spent most of his life rooting around for money, as he lived well beyond his means), but made it known to kings and nawabs that they could appoint him as a court poet with a generous stipend, and some did. In his later years, after the sacking of Delhi in 1857, he lamented that there was none left who could appreciate his work.

However, he was confident of his legacy, as he states in a couplet: “My poetry will win the world’s acclaim when I am gone.” FOSS creators too write for the passion and pleasure of writing great software and be acknowledged as great programmers, than for money alone. The lure of money cannot explain why an operating system like Linux, which would cost about $100 million to create if done by professional programmers, is created by hundreds of programmers around the world through thousands of hours of labour and kept out on the Internet for anyone to download and use for free. The urge to create such high quality software is derived from the passion to create perfect form and structure. A passion that Ghalib shared.

(Rahul De' is Hewlett-Packard Chair Professor of Information Systems at IIM, Bangalore)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)