|

| Kevin Pietersen: an inventor who outwits and confounds © Getty Images |

| Enlarge

|

|

|

|

Half a century ago, Willie Mays was baseball's Garry Sobers. He ran like the wind, possessed a bone-chilling throw, maintained a sturdy batting average, and biffed home runs by the truckload. A superb centre-fielder, he also claimed the game's most celebrated catch, an over-the-shoulder number in the 1954 World Series that still inspires awe for its athleticism, spatial awareness and geometric precision.

Almost without exception, white New York sportswriters said he was gifted: the inference many drew was that this man, this black man, had succeeded not through hard work but because he had been granted a God-given head start. Even if you somehow manage not to classify this as racism, it remains deeply insulting.

"Gifted" is still shorthand for unfeasibly and unreasonably talented. We use it all the time in all sorts of contexts, mostly enviously. Wittingly or not, the implication is that the giftee has no right to fail. Hence the ludicrous situation wherein David Gower aroused far more scorn than Graham Gooch yet wound up with more Ashes centuries and a higher Test average.

Nature v nurture: has there ever been a more contentious or damaging sociological debate? Its eternal capacity to polarise was borne out last week when the

Times devoted a hefty chunk of space to the views of two sporting achievers turned searching sportswriters, Matthew Syed and

Ed Smith. Here was a fascinating clash of perspectives, not least since both have recently written books whose titles attest to the not inconsiderable role played by chance: Syed's

Bounce and Smith's

Luck.

In the red corner sits Syed, a two-time Olympian at table tennis. Referencing the original findings of the cognitive scientist Herbert Simon, winner of the 1978 Nobel Prize, he supported the theory espoused by Malcolm Gladwell, who argued in his recent book Outliers that success in any field only comes about through expertise, which means being willing to put in a minimum of 10,000 hours' practice.

Smith, the former England batsman and Middlesex captain who

writes so thoughtfully and eloquently for this site, takes his cue from

The Sports Gene: What Makes the Perfect Athlete, a new book by the American journalist and former athlete David Epstein, who takes issue with Gladwell.

Genetic make-up, Epstein concludes, is crucial. Usain Bolt, as he stresses, is freakishly tall for a sprinter. He also cites the example of Donald Thomas, who won the high jump title at the 2007 World Athletics Championships just eight months after taking his first serious leap. The key was an uncommonly long Achilles tendon, which doubled as a giant springboard. Subsequent practice, however, failed to generate any improvement. But if we insist, simplistically, that athletic talent is a gift of nature, counters Syed, echoing academic research, this can wreck resilience. "After all, if you are struggling with an activity, doesn't that mean you lack talent? Shouldn't you give up and try something else?"

The debate is rendered all the more complex, of course, by its prickliest subtext. Having conducted a globetrotting survey of attitudes, one "eye-opener" for Epstein was the reluctance of scientists to publish research on racial differences. Fear of the backlash continues to trump the need for understanding.

| | | | |

| |

| Sport is uniquely taxing because it asks young bodies to do the work of seasoned minds |

| |

| | |

|

These delicate issues and stark divergences of opinion, though, mask a deeper, more pertinent and resonant truth. To give nature all the credit is to deny the capacity for change; to plump for nurture is to ignore the inherent unfairness of genetics. Isn't it a matter of nurturing nature? Besides, surely success is more about application. Possessing gallons of ability is no guarantee if, like Chris Lewis, who promised so much for England in the 1990s and delivered conspicuously less, you lack the wherewithal to take full advantage. And if skill was the sole prerequisite, how did Steve Waugh become the game's most indomitable force?

Where would Waugh have been without determination? The same could be asked of the game's two most powerful current captains, MS Dhoni and Michael Clarke. Without that inner drive, would Dhoni have emerged from his Ranchi backwater? Would Clarke have risen from working-class boy to metrosexual man? Ah, but is determination innate or learnt? Cue a cascade of further questions. How telling is environment - social, economic and geographic? Does it have more impact during childhood or adulthood? Is temperament natural or nurtured? Can will be developed? Is confidence instinctive or acquired? I haven't the foggiest. All I can say with any vestige of certainty is that, when preparing a recipe for success, limiting ourselves to a single ingredient seems extraordinarily daft and utterly self-defeating.

So here's another thought. Given that, for the vast majority, achieving sporting success invariably involves battling against at least a couple of odds, surely courage has something to do with it: the courage to overcome prejudice, disadvantage or fear of failure. The courage to perform when thousands are urging you to fail - or, worse, succeed. The courage to take on the bigger man, the better-trained man, to stand your ground, put bones at risk, resist defeatism. The courage not just to be different but act different. The courage not to play the percentages. The courage not to be cautious. The courage to try the unorthodox, the outrageous. The courage to risk humiliation. And the courage, after suffering it, to risk it again.

|

| Shane Warne: one of those rare cricketers who aspired to something loftier than mere excellence © Getty Images |

| Enlarge

|

|

|

The older we get, theoretically at least, the safer we feel and the less courage we need. The less courage I need, the more I admire it in others, hence the growing conviction that bravery exerts the foremost influence on a sportsman's fate, as critical on the field as in the ring or on chicane. In team sports, it is even more imperative: sure, the load can be shared, but it still takes a special type of courage, of nerve, to satisfy the selfish gene - i.e. express yourself - while serving the collective good.

What makes this even more complicated is that when sportsfolk most need courage - between the ages of, say, 14 and 40 - few have fully matured as human beings. How many of the most powerful business leaders or successful lawyers or respected doctors are under 50? How many of the most eminent actors, musicians, authors or chat-show hosts? Sport is uniquely taxing because it asks young bodies to do the work of seasoned minds.

In cricket, the first test of courage comes early. Of all the factors that dissuade wide-eyed schoolboys from pursuing the game professionally, none quite matches the fear of leather and cork. Even for those at the summit, it remains a fear to be acknowledged, tolerated and respected. As Ian Bell recently highlighted when discussing the delights of fielding at short leg, conquest is impossible.

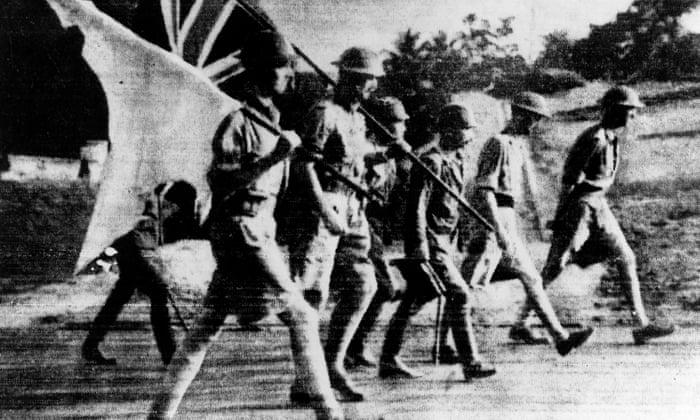

Where the air is rarest and the stakes highest, spiritual courage is even more vital. "I was an outsider. I still am. I didn't do what they wanted." Lou Reed's words they may be, but they could just as easily be the reflections of another couple of performers happy to walk on the wild side, Kevin Pietersen and Shane Warne. That these brothers-in-fitful-charms happen to be 21st-century cricket's foremost salesmen seems far from accidental.

Both are victories for nurture. Both practise(d) with ardour and diligence, mastering their craft, continually honing and refining, then building on it, then honing and refining some more. Both studied opponents assiduously, the better to parry, outwit and confound. Both became inventors, devising daring drives and dastardly deliveries. Yet nature, too, has played a significant role. Both are enthusiasts and positive thinkers. Both radiate self-belief and superiority. Both boast heavenly hand-eye co-ordination. Above all, nonetheless, both aspire(d) to something loftier than mere excellence. Both craved not just to be the best, nor even to dominate, but to astound. To do that takes another very special brand of courage.

For Warne, this meant having the courage to give up one sport and pursue one for which he seemed, physically and temperamentally, far less suited. For Pietersen, it meant having the courage to leave his homeland and to be reviled as both intruder and traitor. Neither, moreover, could completely suppress nature, so they remained true to their gambling instincts and innate showmanship. Without the mental strength to achieve the right balance, such an intricate juggling act would have been beyond them. Perhaps that's what courage really is: the strength to stick to your own path.

Don't take it from me; listen to Bolt: "I'd seen so many people mess up their careers because people had told them what to do and what not to do, almost from the moment their lives had become successful, if not before. The joy had been taken from them. To compensate, they felt the need to take drugs, get drunk every night, or go wild. I realised I had to enjoy myself to stay sane."

Nature versus nurture. Mind versus matter. Means versus ends. Turn those antagonists into protagonists and we might get somewhere. First, though, there must be acceptance: compiling an idiot-proof guide to success is akin to tackling a vat of soup with miniature chopsticks. Besides, if it were easy, there would be more winners than losers. In sport, where success means nothing if nobody fails, that might present a particularly prickly problem.

The best advice? Try Laura Nyro's rallying-cry:

Oh-h, but I'm still mixed up like a teenager

Goin' like the 4th of July

For the sweet sky