Jarrod Kimber in Cricinfo

MS Dhoni is facing Karn Sharma in the playoff, not Harbhajan Singh, despite Harbhajan's economy rate of 6.48 in this IPL. Harbhajan has been dropped partly because Rising Pune Supergiant are playing only one left-hander. Dhoni's figures this season are poorer against spin than pace, and when the quicks come on, he gets short balls and full, wide balls, because he doesn't score quickly from those. He then faces Mitchell McClenaghan, not Lasith Malinga, because Dhoni has a better record against Malinga, and because McClenaghan has overs left since he doesn't get used in the middle overs (where he gets smashed for more than 13 an over). Dhoni ends with 40 off 26, because he scores quickly at the death, where his strike rate this season has been 188.

This is what T20 cricket is becoming: a game of speed chess. Think of how far T20 has already come from the first T20 international, a game where players wore comedy wigs and retro kit. Now teams have general managers with business backgrounds and bat-swing gurus are looking for hitting power, teams are flirting with virtual reality, and league cricket - not international - is a driving force for change. And for all the changes and innovations we have already seen, so many more may yet come.

The closer you look at T20, the more problems, inefficiencies and potential innovations you see, and it is what I've been obsessing about at 2am, which has led me to this piece, which is part prediction, part gripe and part prescription for the near future of T20 cricket.

Do risky second runs make sense?

Running between the wickets is such an integral part of the game that it's incredible how little it is analysed. On his blog , Michael Wagener categorises the different kinds of batsmen in Tests not by where they bat in the order but how they go about their innings. His four categories are: defensive, pushers, block-bash and aggressive. Defensive doesn't exist in T20. Pushers do but are often the improvisers and smartest batsmen. Aggressives and block-bashers are the format mainstays.

Wagener uses David Warner as the stereotypical aggressive player. Warner has always been known as a big-hitter, but his running between wickets is just as bullish. He likes to score off every ball; he steals singles, pushes hard to turn ones into twos, and he takes as many chances with his running as he does with his strokeplay.

The stereotypical block-basher is Chris Gayle. There are few players more content with blocking or leaving the ball than Gayle. And while his slow starts sometimes cost his team, when he does stay in for more than 30 balls, he usually more than makes up. But Gayle has been running singles like his hamstring is gone for almost ten years; he doesn't push hard.

Gayle's method makes sense even if he isn't trying to score from every ball like Warner is. In the IPL, 10% of all dismissals are run-outs (just over 7% for openers). Warner is at 6% in his career. Gayle is at 1%; he's had one run-out in 86 IPL innings, meaning he is effectively cancelling out one mode of dismissal. Gayle gives up risky singles for more boundary attempts, which, for him, carry less risk. It is similar to the trend in basketball to move away from the mid-range two-pointers and replace them with three-pointers, because while you might hit them less often, they're worth more.

In the 2016 World T20, most of Gayle's team-mates played that way. West Indies had seven players in the top 25 of batsmen who scored the highest percentage of their runs in boundaries (minimum 50 runs); Gayle and Carlos Brathwaite were ranked two and three. And it raised the question of what batsmen should be expending their energy on: risky second runs, or risky boundary attempts? And instead of turning the strike over to put pressure on the bowler, perhaps big-hitting batsmen should face multiple balls in a row, allowing them to find rhythm and size the bowler up better.

Gayle scampers a quick single. Would the data advocate otherwise? © ICC/Getty

Gayle scampers a quick single. Would the data advocate otherwise? © ICC/Getty

Or: Glenn Maxwell has a strike rate of 264 between overs 13 and 16, higher than any other player in any other period in this year's IPL. If he is facing in the 14th, do you want him taking a risky single and getting a slower batsman on strike, or do you want to bowl a dot and have him face the next ball?

How do fast batsmen run? How productive are coaching methods for running between wickets? Currently coaches are trying to train intent into batsmen, but outside of full match simulations, there seems to be no clear method to turn an average runner into a good one.

How about facing tempo? Some players are happy to stand at the non-striker's end for a long time, while others get frustrated, which often leads to their wickets. More data is needed for this, as wickets are probably falling because a batsman is not letting his partner strike the ball enough, or vice versa. As teams look for one-percenters, running could be one place they find some.

A more context-driven measure for a player's effectiveness

We know how many runs every over is worth on average in T20 and yet we still talk about players' overall strike rates. There are four periods in T20 for which you look at numbers: the Powerplay, the lull from overs 7 to 12, the ramping up between overs 13-16, and the death from 17-20. For most players, their career strike rate or economy rate is defined by what period they appear in the most.

A bowler (many wristspinners, for example) who starts in the seventh over and bowls the majority of his overs during the lull will have a better economy than someone who bowls more in the Powerplay and death. These splits tell us who the best players are, and where players can improve.

For batsmen the most obvious place for improvement is in the lull, where the game drifts. This IPL season Rohit Sharma, Shreyas Iyer and Shikhar Dhawan scored at a run a ball in this period, while Robin Uthappa (207 runs) and Aaron Finch (202) scored at more than two runs a ball.

Almost all batsmen can smash the ball at the death, but the real key is if you can score above the going rate for any specific period consistently. A strike rate of 150 sounds great at the death, but it's lower than the average rate for that period. You only have to check the lull overs to see a bunch of batsmen are going far too slow, ending up with good averages but not adding a lot of extra value.

With something as simple as a plus or minus on your strike rate or economy rate, you could instantly tell which players were playing above or below the average. So instead of a pure strike rate, a figure would be adjusted to each ball of the innings they played (we know how many runs each ball in T20 goes for). On a game-by-game basis it isn't as important, but over a season, or career, you can work out if a player added value or lost it based on their true strike rate or economy rate.

Spotting bowling patterns (or not)

Batsmen have only recently embraced video analysis to determine the patterns of bowlers. Before, they would base it on their experiences, not insights from data. One analyst told me a story of batsmen noticing that Jade Dernbach would almost always follow up being hit for a boundary with a back-of-the-hand slower ball. The analyst thought they figured it out through natural batting intuitions, not through analysis.

Rohit Sharma is one of several batsmen who are too sluggish during the middle overs © BCCI

Rohit Sharma is one of several batsmen who are too sluggish during the middle overs © BCCI

Bowlers can change, and while it is not definitive, Dernbach's death-bowling economy rate over the last two county seasons is 7.8, which is brilliant, and suggests that it is possible he doesn't follow his old patterns anymore (or he is just prospering among the lower level of players in English domestic cricket).

Something like this was probably on R Ashwin's mind when he said: "six well-constructed bad balls could be the way to go forward in T20 cricket". Ashwin knows that on most occasions bowling six well-grouped offspinners together will allow batsmen to know what he bowls, and he'll go the distance. So what we normally of think of as a good ball is not a good ball in T20, and instead Ashwin might have to "construct" a random pattern of what look like bad balls in order to stay one step ahead of the batsman.

Jasprit Bumrah bowled the penultimate over of the IPL this year and the commentators talked about its quality. When he was hit for six off a half-volley, they mentioned how rarely he misses the yorker. But he also bowled two knee-high full tosses and, as neither went for boundaries, nobody focused on them as mistakes. So Dernbach's best ball is smashed, Bumrah's worst is mishit, and Professor Ashwin's theory might be slightly flawed, but you can see why not letting the batsman know what is coming next is the best option.

Will we see batting cages near the dugout?

The idea that you just go out there and smash your first ball for six isn't quite how T20 is played. Even the most aggressive players generally have a strike rate of less than a run a ball over their first five balls. You have to get your eye in, cricketers are taught; and T20 is still a new invention, so teams and players are working it out. But it still hasn't been drilled into players that every single ball is 0.83% of the innings, and one over to settle in is 5% of your team's quota.

The first team to strike well from ball one will have a huge advantage. Perhaps the best way to try to achieve this is through batting cages, or a fully enclosed batting net on the boundary edge. That way the next batsman in is playing himself in right up to the point he gets to the middle.

It may not be exactly the same as being out in the middle, but it's as close to it as we can currently get. Every analyst, general manager or coach I've talked to is frustrated batsmen don't start quicker, and yet teams still aren't trying to ensure that batsmen feel like they are already in before they walk in.

Balls are also wasted in T20 when batsmen approach milestones. Milestones in cricket have long been millstones around batsmen's necks. Cricket is a weird hybrid of individual skills and battles within a team sport. We see it all the time; the player is smashing the ball and suddenly gets near his milestone and starts chipping it around. Australian players have been encouraged to try and forget about this, but in franchise cricket, where so much of your worth comes down to people remembering how well you did, it's hard for players not to waste a few extra balls when you're in the forties or nineties.

Bat lean, bat efficient

Imran Khan, an analyst for CricViz, looked at the boundary attempts made by batsmen in this IPL. Finch tries to hit a boundary every 1.81 balls and succeeds 45% of the time. Manan Vohra attempts a boundary every 3.44 balls and has a 69% success rate. They are two of the leaders on the metrics of balls per boundary attempt and the success rate of their attempts. But the real eye-catcher is Sunil Narine, second on the list with a 68% success rate from his attempts, and one attempt every 2.16 balls (fifth). There are all sorts of other interesting finds, like the fact that the slog sweep is the shot most likely to produce a boundary, and even that only works 40% of the time.

"Here comes another fiendishly clever bad ball" © BCCI

"Here comes another fiendishly clever bad ball" © BCCI

This is just the beginning for cricket when it comes to measuring the efficiency of batting. At ESPNcricinfo we've been using a batting metric called control stats, to judge whether a batsman was in control of the shot he played (an edge, for example, is not in control). Like CricViz's boundaries attempted, it is recorded by an analyst, and so is subjective.

Other sports use algorithms and technology for this analysis. Basketball has SportsVu cameras above the court and spatiotemporal pattern recognition - a science that provides insights into human movements - to decide the success probability of each shot. The software has essentially worked out all the different kinds of shots and plays in basketball, through algorithms and the footage.

The same could eventually be done for cricket. A slog over midwicket off a tall bowler on a pitch with above-average bounce is probably going to be successful fewer times compared to a straight drive off a half-volley from a shorter, skiddier bowler with mid-on and mid-off up. Spatiotemporal pattern recognition could completely change the way the game is played. We'd get real, objective information on the worth of fielders, wicketkeepers, running between wickets, bowling and batting; information that could provide a huge leap forward for the way T20, and eventually all cricket, is played.

Fielding metrics are going to be important

There is a plan for every ball of a T20 match, yet the game still doesn't really map where fielders stand for each ball. The best way to do it would be an overhead camera that catches all data from the game. Devices such as the Australian-invented Catapult, which players wear between their shoulder blades, give interesting data of player movement and fitness levels, but not fielding maps.

There is no reason that fielding maps can't be more widely used by analysts at the ground, or even if TV companies wake up and start showing live fielding changes in a small box on the screen. Cricket's first data-led analyst, Krishna Tunga (the Bill James to John Buchanan's Billy Beane), has done some work with fielding data But in reality there is very little written or thought about fielding, unless a captain has what we believe to be a shocker. But fields change almost every ball in T20; it is a massive part of the game, and yet how often are fielding strategies part of the reasons teams lose according to experts? A big part of that is the lack of stats and data.

Even in a Test we have no idea if a bowler performs better with three slips and a third man, or two slips and a ring field. Maybe the bowler feels one suits him more, and the captain another. But the best option might never be chosen simply because they don't have actual data to back up their feeling. In T20, we still don't have stats for how a batsman scores against individual fields.

Baseball took years to work out that shifting the field for specific batters was important. Cricket has been doing it since the start, but it's just not noted - there are wagon wheels of innings from the 1800s. If you allied modern technology - a real-time video fielding map, for example - to the ancient wagon wheel, you could actually see where a batsman scored his runs, and whether or not he was exploiting the fields that were set.

The slow ball is important, but how well do we know it?

At the exact time that spinners seem to be getting quicker, fast bowlers are spinning the ball more than ever. Whether it is the standard slower balls that Dwayne Bravo or Thisara Perera bowl, or the fast spinners Mustafizur Rahman does, seam bowling in T20 cricket is more about rotating the seam than keeping it straight.

Statistically, the slog sweep is the shot most likely to produce a boundary © Cricket Australia

Statistically, the slog sweep is the shot most likely to produce a boundary © Cricket Australia

And yet for all the slower balls delivered, we still don't have much information on how often they are bowled, or how successful they are. CricViz occasionally tweets about bowlers' records with slower balls. From ball-tracking data they can tell you the percentage of slower balls (classifying everything under 77mph as slow): Bumrah (25%), Lasith Malinga (17%), Mitchell McClenaghan (16%), and Albie Morkel (16%). Because they don't always have access to ball-tracking, and some bowlers who bowl slower balls don't have a top speed much above 77mph, they also use analysts to manually log slower balls. Using that data, we know that Bravo bowls slower balls 34% of the time, and that Malinga's bowling average for slower balls is 8.15 and Kevon Cooper's is 9.76.

Numbers like this will help fans understand the true worth of bowlers like Rajat Bhatia. But at this point we don't even know which batsmen play slower balls well, though it is something we could figure out just by looking at a batsman's strike rate and average against slower balls (which will in future probably be further split between back-of-the-hand, knuckleballs and offcutter slow balls).

Making sense of the data

Match-ups - like pitting a left-arm spinner against a player who struggles against them - are already happening. Some teams go further into individual contests, of players against other players. The problem right now is that the sample sizes are very small. The bowler who delivered the most balls to any one batsman in this year's IPL was Kuldeep Yadav to Warner: just 25 balls.

T20 has many different competitions, all played in completely different conditions, with different players. Baseball match-ups produce bigger samples, but in the IPL there is only one contest that has over 100 balls: Suresh Raina v Harbhajan (which Harbhajan is winning, with an average of 26 and economy of 6.6). So while it is interesting that Ashwin has never taken Virat Kohli's wicket in 97 balls, and that Rohit Sharma has a strike rate of 84 against Ashwin, in the history of the IPL there are only 132 match-ups of more than 50 balls.

The top four bowling strike rates between overs seven and 12 in T20 (minimum 36 balls) over the last couple of years belong to David Willey (208), Sharjeel Khan (190), Gayle (179), and Patrick Kruger (177). One plays the T20 Blast, Big Bash and T20 internationals, another plays the PSL and internationals, the third plays everydamnwhere, and the fourth is a 22-year-old who plays for Knights and Griqualand West in South Africa. This is not like for like.

That doesn't mean there aren't certain trends that are pretty clear across all leagues, but there are league-specific trends. In South Africa, 8% of all Powerplay overs are bowled by spinners. That is less than in England (12%), nowhere near Australia (23%), and not even in the same ballpark, so to speak, as in the Caribbean (35%). So someone picking a South African opening batsman with little experience outside South Africa for the CPL constitutes a huge risk. And even in a league like the BBL, where you are facing more spin at the top of the innings, it is a completely different kind of spinner, on a completely different kind of wicket.

But data is certainly a very good tool, not just in selection, or coaching, but in game situations. A player recently asked me to look into his career stats and see if there were any areas he could work on as he freelances his way around the world. I found that he has an incredible record when he comes in further down the order, and that when he comes in higher, he's not as effective. He turned from a late-order champion to an average middle-overs player. He said that he had been batting higher because he and his most recent coach were worried he was coming in too late. When I looked into the details, there hadn't really been a game where he came in too late; it was just the perception, perhaps, of a player who was watching balls he assumed he could hit for six, and maybe a coach who felt the same.

The game's next big innovations might well emerge from data sets © Getty Images

The game's next big innovations might well emerge from data sets © Getty Images

While most of the pioneering will happen in T20 leagues, international cricket will catch up. Cricket has never been changing faster than it is now. T20 is finding trends and abandoning them quicker than you can say "Sunil Narine, opening batsman".

As the technology, methods and people from T20 end up in international cricket, we will see changes there as well. By recruiting people like Pat Howard (rugby) and Kim Littlejohn (lawn bowls) international cricket has already shown it is open to outside ideas and perspectives. The next big move will be when people from the finance and corporate world, who are starting to take over as decision-makers in franchise cricket, move to international cricket.

We are probably only a few years away from international cricket's first GM who isn't a former player, has come from a non-sporting background, and is calling the shots on how international squads are put together.

The battle to make every last run is no longer just on the field, it's in algorithms and data sets, and cricket's next big change is as likely to come from a laptop as it is a bat.

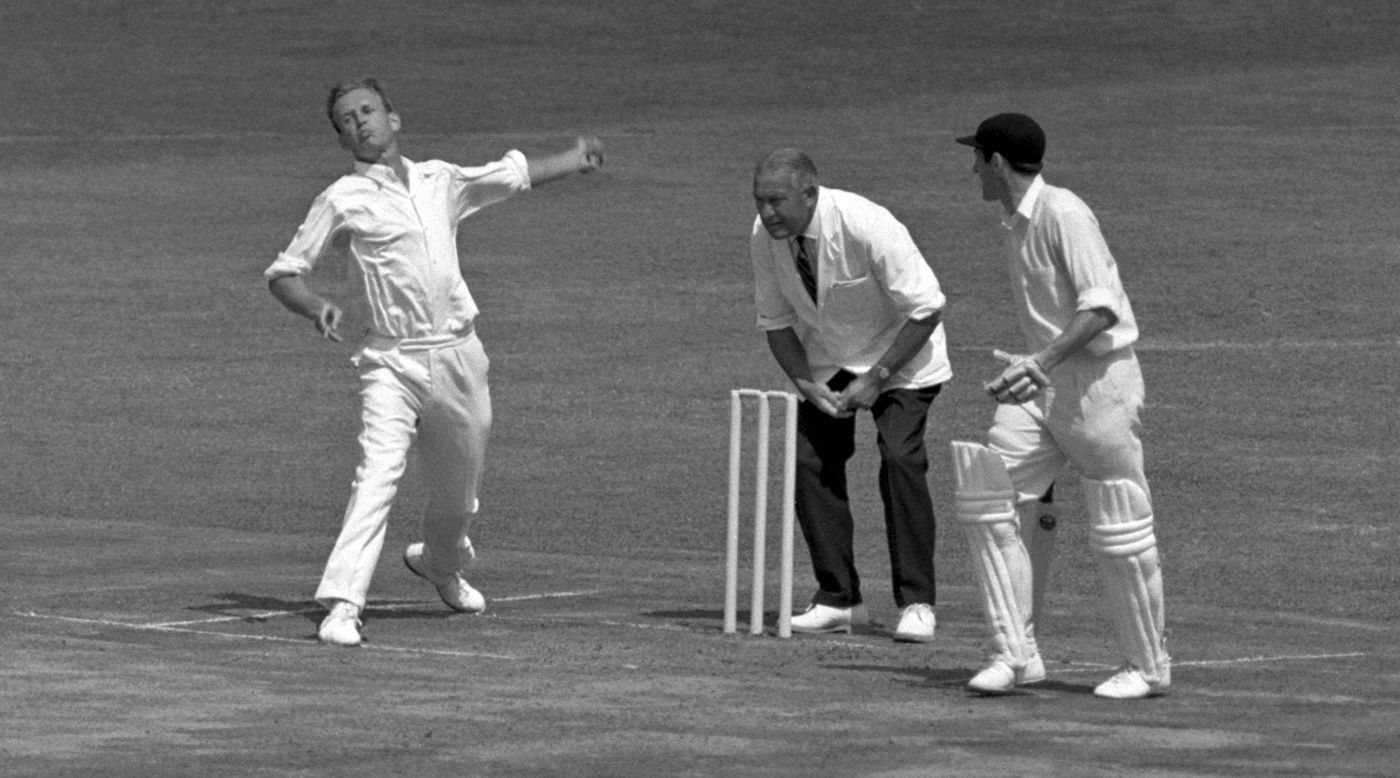

On wet wickets, Derek Underwood would bowl cutters © PA Photos

On wet wickets, Derek Underwood would bowl cutters © PA Photos