'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label amateur. Show all posts

Showing posts with label amateur. Show all posts

Sunday, 20 June 2021

Thursday, 10 September 2015

Technology and the amateur cricketer

Jon Hotten in Cricinfo

The professional cricketer lives an examined life, with feedback from various corners © Getty Images

The professional cricketer lives an examined life, with feedback from various corners © Getty Images

Every journalist knows the horror of their own voice. The realisation comes early, when you begin recording interviews. There, on the tape or in the bytes or the VT, is not the voice you thought that you had, the one that's been echoing in your ears for your whole life, but the one that the rest of the world hears - reedy, nasal, pitched entirely differently.

It takes a while to get over the discovery and to become acquainted with the notion that self-image overlaps only slightly with the objective view of the rest of the world.

Cricket is deep into its age of analysis. Kartikeya Date's lovely piece in the current Cricket Monthly illuminates the depth of it: every ball in every major match is logged, filed, deconstructed. It means that the professional cricketer lives an examined life, and its information comes at them from all angles: their coaches, their laptops, the television, the internet, YouTube, Twitter… a bombardment of feedback that can leave them in no doubt as to what they look like in the eyes of the world. Reality here is absolute, self-image challenged from an early age.

It has a purpose, of course; all of this stuff, and in a sport that exacts a high psychological price, strong self-knowledge can be an important anchor. It's why the analysed player speaks constantly of "knowing my game", "executing my skills" and so on. There is no longer any mystery to how they do what they do and so they take refuge in the empirical evidence of their talents.

The amateur cricketer (apart from the serious, higher-level one) is the polar opposite, a player who relies almost totally on the powers of delusion. In our heads we are younger, stronger, faster and better than ever. Fleeting successes sustain the vision.

The classic response to failure is not to practise more but to buy a new bat or try a new grip or take up a new place in the order. Bowlers gaze at the television and imagine that their pace is up there at the dibbly-dobbly end of the pro game - Paul Collingwood maybe, or David Warner.

Does analysis have a role to play here, where the idea of preparation is a few taps on the boundary edge when you're next in? Can an encounter with the awful reality of your game offer the way towards the radical and constant self-improvement sought and often attained by the professional cricketer?

As with all technologies, the machinery required for analysing cricket is becoming more available as the hardware becomes affordable. As a joint birthday present (and maybe a not-so-subtle hint) our team-mates bought me and my fellow senior player Big Tone a session at the indoor school at Lord's, where they have installed a lane with Pitch Vision technology and another with Hawk-Eye. Pitch Vision ("Come face to face with your own performance outcomes") utilises sensors and cameras to offer immediate video playback and analysis of every delivery on both a big screen behind the net and via downloadable post-session data for perusal at your leisure.

A bowling action in pixels © Getty Images

A bowling action in pixels © Getty Images

Disconcertingly, it also measures the speed of each delivery. Accompanying me and Big Tone (ostensibly both batsmen) is our captain Charlie, who is an opening bowler and as such has more invested in the unyielding outcome of the speed gun.

I watch a playback as a stooped, shuffling figure advances slowly - really slowly - towards the crease before hopping into a round-arm, bent-backed delivery that progresses at a stately 50mph towards the batsman. "Ha!" I think. "Who's that old man…" before the dreaded realisation that, of course, it is me.

In my mind, I have a jaunty and rapid run-up and quite a high arm. The screen before me shatters that illusion forever. Sybil Fawlty's withering description of the hapless Basil as "a brillianteened stick-insect" flashes into my head as I watch myself replayed in super slo-mo. I briefly salvage some self-esteem with a delivery recorded at 62mph before realising that the screen is still showing Charlie's last ball.

The batting was a little better, or at least a little more familiar. I'd seen myself on camera years ago and so my psyche had absorbed the fact that I wasn't exactly King Viv, more of a taller Boycott type, whose defence was nonetheless far more permeable than the great man's. I had, though, an idea that my backlift was high and that I had a dynamic stance ready to push forward or back with coiled power. Sadly it was all more of a non-committed shuffle. Although my bat speed was something of a triumph, especially watching in normal time after a period of slow motion.

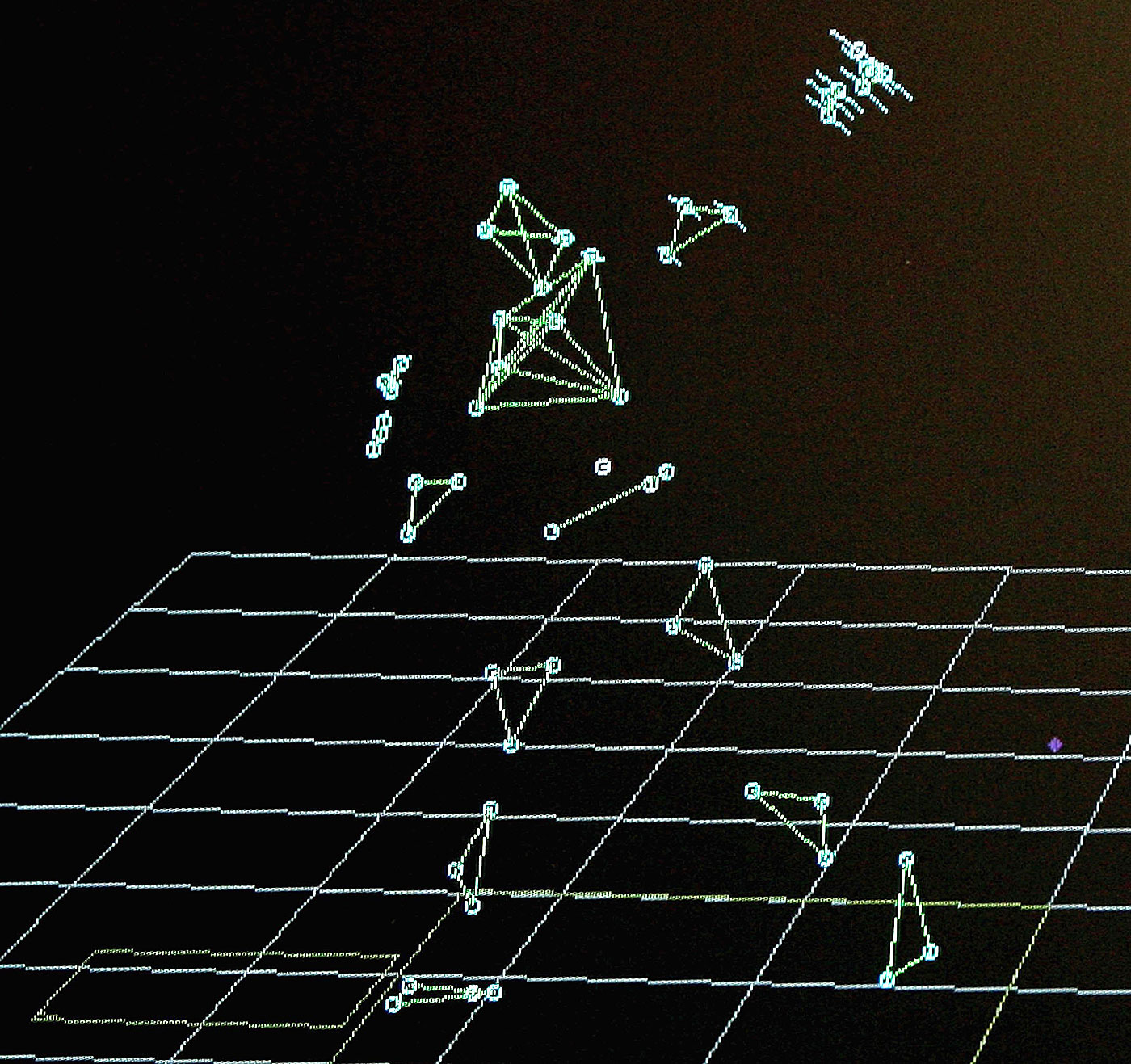

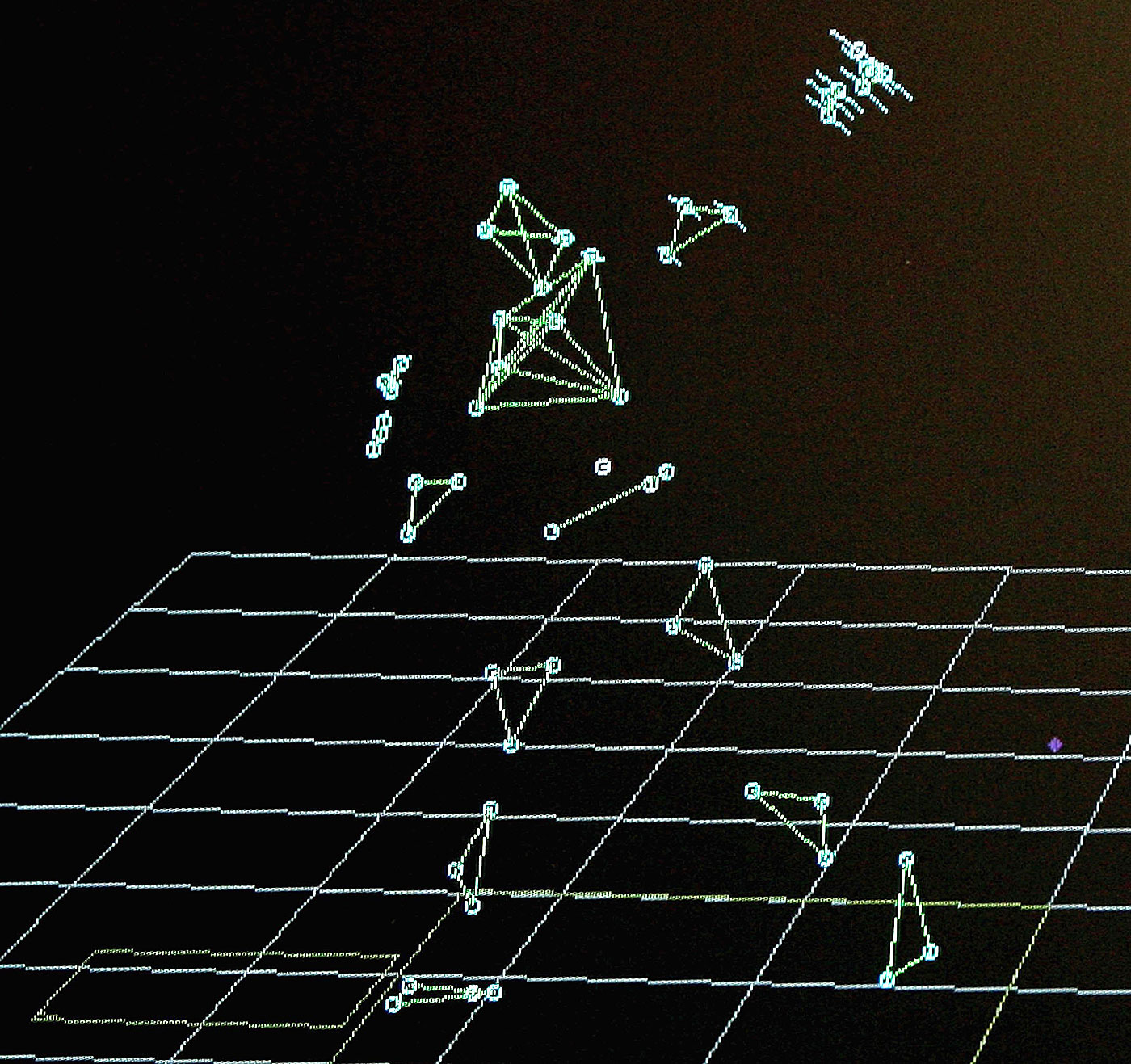

The Hawk-Eye session was equally revelatory. Its on-screen analysis is identical to its televisual output - the beehive, the pitch map, the strike zones and so on - except with very different, and reduced, figures. The finest moment was the side-on ball-tracker of one of Big Tone's medium-pacers. Stopping the gun at 42mph, it ascribed two long and looping parabolas and was actually descending as it hit the stumps. The ball's pathway resembled a 22-yard letter "m".

It was a lot of fun, and illuminated the gulf between the world of the pro cricketer, who must worry and fret about this sort of stuff, and the amateur, who, like me, watched Glenn Maxwell bowl the next day at 57mph with renewed admiration for his pace. In the blinding light of technology's glare, your game is laid bare. It will take me a while to retreat back into the land of comfortable and happily deluded fantasy.

The professional cricketer lives an examined life, with feedback from various corners © Getty Images

The professional cricketer lives an examined life, with feedback from various corners © Getty ImagesEvery journalist knows the horror of their own voice. The realisation comes early, when you begin recording interviews. There, on the tape or in the bytes or the VT, is not the voice you thought that you had, the one that's been echoing in your ears for your whole life, but the one that the rest of the world hears - reedy, nasal, pitched entirely differently.

It takes a while to get over the discovery and to become acquainted with the notion that self-image overlaps only slightly with the objective view of the rest of the world.

Cricket is deep into its age of analysis. Kartikeya Date's lovely piece in the current Cricket Monthly illuminates the depth of it: every ball in every major match is logged, filed, deconstructed. It means that the professional cricketer lives an examined life, and its information comes at them from all angles: their coaches, their laptops, the television, the internet, YouTube, Twitter… a bombardment of feedback that can leave them in no doubt as to what they look like in the eyes of the world. Reality here is absolute, self-image challenged from an early age.

It has a purpose, of course; all of this stuff, and in a sport that exacts a high psychological price, strong self-knowledge can be an important anchor. It's why the analysed player speaks constantly of "knowing my game", "executing my skills" and so on. There is no longer any mystery to how they do what they do and so they take refuge in the empirical evidence of their talents.

The amateur cricketer (apart from the serious, higher-level one) is the polar opposite, a player who relies almost totally on the powers of delusion. In our heads we are younger, stronger, faster and better than ever. Fleeting successes sustain the vision.

The classic response to failure is not to practise more but to buy a new bat or try a new grip or take up a new place in the order. Bowlers gaze at the television and imagine that their pace is up there at the dibbly-dobbly end of the pro game - Paul Collingwood maybe, or David Warner.

Does analysis have a role to play here, where the idea of preparation is a few taps on the boundary edge when you're next in? Can an encounter with the awful reality of your game offer the way towards the radical and constant self-improvement sought and often attained by the professional cricketer?

As with all technologies, the machinery required for analysing cricket is becoming more available as the hardware becomes affordable. As a joint birthday present (and maybe a not-so-subtle hint) our team-mates bought me and my fellow senior player Big Tone a session at the indoor school at Lord's, where they have installed a lane with Pitch Vision technology and another with Hawk-Eye. Pitch Vision ("Come face to face with your own performance outcomes") utilises sensors and cameras to offer immediate video playback and analysis of every delivery on both a big screen behind the net and via downloadable post-session data for perusal at your leisure.

A bowling action in pixels © Getty Images

A bowling action in pixels © Getty ImagesDisconcertingly, it also measures the speed of each delivery. Accompanying me and Big Tone (ostensibly both batsmen) is our captain Charlie, who is an opening bowler and as such has more invested in the unyielding outcome of the speed gun.

I watch a playback as a stooped, shuffling figure advances slowly - really slowly - towards the crease before hopping into a round-arm, bent-backed delivery that progresses at a stately 50mph towards the batsman. "Ha!" I think. "Who's that old man…" before the dreaded realisation that, of course, it is me.

In my mind, I have a jaunty and rapid run-up and quite a high arm. The screen before me shatters that illusion forever. Sybil Fawlty's withering description of the hapless Basil as "a brillianteened stick-insect" flashes into my head as I watch myself replayed in super slo-mo. I briefly salvage some self-esteem with a delivery recorded at 62mph before realising that the screen is still showing Charlie's last ball.

The batting was a little better, or at least a little more familiar. I'd seen myself on camera years ago and so my psyche had absorbed the fact that I wasn't exactly King Viv, more of a taller Boycott type, whose defence was nonetheless far more permeable than the great man's. I had, though, an idea that my backlift was high and that I had a dynamic stance ready to push forward or back with coiled power. Sadly it was all more of a non-committed shuffle. Although my bat speed was something of a triumph, especially watching in normal time after a period of slow motion.

The Hawk-Eye session was equally revelatory. Its on-screen analysis is identical to its televisual output - the beehive, the pitch map, the strike zones and so on - except with very different, and reduced, figures. The finest moment was the side-on ball-tracker of one of Big Tone's medium-pacers. Stopping the gun at 42mph, it ascribed two long and looping parabolas and was actually descending as it hit the stumps. The ball's pathway resembled a 22-yard letter "m".

It was a lot of fun, and illuminated the gulf between the world of the pro cricketer, who must worry and fret about this sort of stuff, and the amateur, who, like me, watched Glenn Maxwell bowl the next day at 57mph with renewed admiration for his pace. In the blinding light of technology's glare, your game is laid bare. It will take me a while to retreat back into the land of comfortable and happily deluded fantasy.

Monday, 6 April 2015

The art of (amateur) cricket captaincy

Charlie Campbell in The Guardian

No cricket captain needs an ECB survey to tell him what he already knows – that playing numbers in England are in decline. The last game of the season is always the most important one for the amateur skipper. By then, up to half of your players will be deciding whether to play next year, whether they’ll put up with the aches, strains and strife that a full summer of cricket brings. But a decent team performance can erase untold painful memories from earlier in the season and a good individual one will banish all winter’s doubts. You just have to coax enough runs or wickets from those players to ensure you have a full team next year.

This is not a problem that the professional captain faces. Those at the pinnacle of the game can choose from the country’s 844,000 active cricketers – though realistically only the last 4,000 are in the running. The remaining 840,000 of us are making up the numbers. And despite these numbers, many amateur captains will struggle to put out a full XI every weekend. Mike Brearley’s The Art of Captaincy brilliantly describes the challenges that he faced on the cricket field when leading England to Ashes glory in 1981. But he never had to play with nine men.

That is just one of the problems the amateur captain faces. It is perfectly normal for players to drop out on the eve or morning of a game. If this happens in Saturday league cricket, the first team takes the seconds’ star all-rounder but will bat him at 10 and won’t bowl him. The seconds will plunder the thirds for their best batsman and probably won’t give him back. The thirds will reluctantly borrow someone from the fourths, hoping he won’t let them down too much. And the fourths will be short, again, and may have to find something else to do that afternoon.

But league cricket is a distant relation to the professional game. And Sunday cricket is something entirely separate again, and requires a different mindset. This version of the game, perfected over centuries in villages all round England, is the beating heart of cricket. It’s where players are born and die: where once-good cricketers are put out to pasture, fathers and sons play together and where the unselectable finally get a game.

As amateur captain you hope to keep all your players happy. Some will be competent cricketers, others won’t and at least one will not have played before. But you have to forge a team out of them. At this lower level of cricket you try to involve everyone in the game one way or another. Ideally you will have a pair of good batsmen, a competent keeper and a couple of decent bowlers. Hopefully they won’t be the same two people. Then it’s like a game of chess, in which you match up your strong pieces against the opposition’s queen and rooks, and let the pawns fight it out.

Not only do you have to husband your resources carefully, but you won’t always be playing to win. Match-fixing – or match management as we prefer to call it – may be the scourge of the professional game, but it is a key aspect of Sunday cricket and perhaps the only thing that amateurs do better than the professionals.

Although not every captain adheres to these principles, usually both sides want a good close game. A one-sided match is enjoyable for the dominant players, but when the outcome is so predictable, the rest lose heart and interest. They all know how the story ends and that they’re not the hero. So sometimes it pays to take the pressure off for an over or two and let the opposition regroup. After all, you don’t want the game to be over by tea.

How I came to own the sweater Wasim Akram wore at the 1992 World Cup final

Read more

There are various ways of doing this but, however you do it, discretion is key – just as it was for Hansie Cronje or Salman Butt. You shouldn’t be asking anyone to underperform, nor be doing so yourself. I’ve never deliberately bowled a full toss, wide or no-ball – there are many better ways to alter the balance of a game. You give a weaker bowler a couple of overs too many, with an attacking field. Your cannier teammates may guess what’s going on, but the rest won’t. They’ll be too busy thinking about their own game.

But this tends to happen after the opposition has lost five quick wickets and is a hundred runs short of a competitive total. What is rare is having to match manage from the outset. It has only happened to me once. I captain a team of writers and we tend to play teams that are a little bit stronger than us. After all, authorship usually comes in the later decades of life, and consequently, our squad is long on experience but short on speed and agility.

This particular day we were playing a team of a similar vintage. I walked out with their captain for the toss and we had the standard conversation about the respective strengths of our teams, and agreed a 20-over format. One of cricket’s great joys is that things are not always what they seem. I’ve seen septuagenarians bowl maiden after maiden, morbidly obese batsmen strike quick fifties, and small children throw the stumps down from 30 yards. But as I looked at the opposition, I was pretty sure that appearances didn’t mislead and that we were the stronger side. I called correctly and put them in, thinking that it would be easier to control the game that way. We had a decent team, with enough bowling and batting to cruise to a sporting win.

I was already fretting after just two overs. Their score stood at two for no loss as the openers took a circumspect approach to batting. Chris Gayle often plays out a maiden before unleashing hell in the next over. But these two played more like Chris Tavaré and showed no signs of wanting to accelerate. At this rate we would be lucky to be chasing more than 50.

After four overs, I turned to spin, telling the surprised new bowler that I was keeping myself back for their No3, whom I knew to be their best player. (At our level, few spinners hit the stumps regularly. Each ball comes out of the hand differently. Then there’s the variation the bowler feels it necessary to add, having zealously watched clips of Warne in action. The result is always six very different deliveries, which will include a full toss, a wide and one that bounces twice. It is almost impossible not to score at least five an over off a bowler such as this, particularly if the field includes two slips and a couple of gullies as mine did. Full tosses can be hit to fielders and double bouncers sometimes pass under the bat onto the stumps.) And so the opposition’s score crept up but the wickets fell too. The No3 came and went without living up to the reputation I’d given him. But their No4 made a quick-fire 30 and they finished on a respectable 98 in their 20 overs. Meanwhile, our two occasional spinners recorded their best figures of the season.

Why do we play cricket?

Read more

Half the match had passed and while I hadn’t been actively trying to lose, nor had I been trying to win. I was giving players opportunities they didn’t always get and they were enjoying it. My competitive instinct would typically have returned now, with a total to chase, but I looked around at my team and I saw various players yet to make a decent score this season. This could be the day they did so, if the opposition’s bowling was anything like their batting. And so I put two of our tail-enders at 3 and 4.

Both were clean bowled, making five runs between them, but our spin duo played their best innings of the summer, taking us from 30 for 3 after nine overs to a position where we needed 24 from the last 18 balls. Our youngest batsman, the teenage son of one of our players, hit a few boundaries but couldn’t get the four needed from the last delivery. And so we lost. It felt strange losing like that to a weaker side but I felt we had salvaged something from what could have otherwise been an awful day’s cricket.

Even supposing the captain succeeds in getting 11 players on the field, against that ideal opposition, there still remain infinite ways in which things can go wrong. At least one player will get lost driving to an away game – and home matches are no better, since those who turn up early have to prepare the ground, put out boundary flags and sightscreens. Another player will have forgotten his whites. And pity the skipper who discovered that his first slip had taken ecstasy during the tea interval. Brearley never had to deal with that either.

No cricket captain needs an ECB survey to tell him what he already knows – that playing numbers in England are in decline. The last game of the season is always the most important one for the amateur skipper. By then, up to half of your players will be deciding whether to play next year, whether they’ll put up with the aches, strains and strife that a full summer of cricket brings. But a decent team performance can erase untold painful memories from earlier in the season and a good individual one will banish all winter’s doubts. You just have to coax enough runs or wickets from those players to ensure you have a full team next year.

This is not a problem that the professional captain faces. Those at the pinnacle of the game can choose from the country’s 844,000 active cricketers – though realistically only the last 4,000 are in the running. The remaining 840,000 of us are making up the numbers. And despite these numbers, many amateur captains will struggle to put out a full XI every weekend. Mike Brearley’s The Art of Captaincy brilliantly describes the challenges that he faced on the cricket field when leading England to Ashes glory in 1981. But he never had to play with nine men.

That is just one of the problems the amateur captain faces. It is perfectly normal for players to drop out on the eve or morning of a game. If this happens in Saturday league cricket, the first team takes the seconds’ star all-rounder but will bat him at 10 and won’t bowl him. The seconds will plunder the thirds for their best batsman and probably won’t give him back. The thirds will reluctantly borrow someone from the fourths, hoping he won’t let them down too much. And the fourths will be short, again, and may have to find something else to do that afternoon.

But league cricket is a distant relation to the professional game. And Sunday cricket is something entirely separate again, and requires a different mindset. This version of the game, perfected over centuries in villages all round England, is the beating heart of cricket. It’s where players are born and die: where once-good cricketers are put out to pasture, fathers and sons play together and where the unselectable finally get a game.

As amateur captain you hope to keep all your players happy. Some will be competent cricketers, others won’t and at least one will not have played before. But you have to forge a team out of them. At this lower level of cricket you try to involve everyone in the game one way or another. Ideally you will have a pair of good batsmen, a competent keeper and a couple of decent bowlers. Hopefully they won’t be the same two people. Then it’s like a game of chess, in which you match up your strong pieces against the opposition’s queen and rooks, and let the pawns fight it out.

Not only do you have to husband your resources carefully, but you won’t always be playing to win. Match-fixing – or match management as we prefer to call it – may be the scourge of the professional game, but it is a key aspect of Sunday cricket and perhaps the only thing that amateurs do better than the professionals.

Although not every captain adheres to these principles, usually both sides want a good close game. A one-sided match is enjoyable for the dominant players, but when the outcome is so predictable, the rest lose heart and interest. They all know how the story ends and that they’re not the hero. So sometimes it pays to take the pressure off for an over or two and let the opposition regroup. After all, you don’t want the game to be over by tea.

How I came to own the sweater Wasim Akram wore at the 1992 World Cup final

Read more

There are various ways of doing this but, however you do it, discretion is key – just as it was for Hansie Cronje or Salman Butt. You shouldn’t be asking anyone to underperform, nor be doing so yourself. I’ve never deliberately bowled a full toss, wide or no-ball – there are many better ways to alter the balance of a game. You give a weaker bowler a couple of overs too many, with an attacking field. Your cannier teammates may guess what’s going on, but the rest won’t. They’ll be too busy thinking about their own game.

But this tends to happen after the opposition has lost five quick wickets and is a hundred runs short of a competitive total. What is rare is having to match manage from the outset. It has only happened to me once. I captain a team of writers and we tend to play teams that are a little bit stronger than us. After all, authorship usually comes in the later decades of life, and consequently, our squad is long on experience but short on speed and agility.

This particular day we were playing a team of a similar vintage. I walked out with their captain for the toss and we had the standard conversation about the respective strengths of our teams, and agreed a 20-over format. One of cricket’s great joys is that things are not always what they seem. I’ve seen septuagenarians bowl maiden after maiden, morbidly obese batsmen strike quick fifties, and small children throw the stumps down from 30 yards. But as I looked at the opposition, I was pretty sure that appearances didn’t mislead and that we were the stronger side. I called correctly and put them in, thinking that it would be easier to control the game that way. We had a decent team, with enough bowling and batting to cruise to a sporting win.

I was already fretting after just two overs. Their score stood at two for no loss as the openers took a circumspect approach to batting. Chris Gayle often plays out a maiden before unleashing hell in the next over. But these two played more like Chris Tavaré and showed no signs of wanting to accelerate. At this rate we would be lucky to be chasing more than 50.

After four overs, I turned to spin, telling the surprised new bowler that I was keeping myself back for their No3, whom I knew to be their best player. (At our level, few spinners hit the stumps regularly. Each ball comes out of the hand differently. Then there’s the variation the bowler feels it necessary to add, having zealously watched clips of Warne in action. The result is always six very different deliveries, which will include a full toss, a wide and one that bounces twice. It is almost impossible not to score at least five an over off a bowler such as this, particularly if the field includes two slips and a couple of gullies as mine did. Full tosses can be hit to fielders and double bouncers sometimes pass under the bat onto the stumps.) And so the opposition’s score crept up but the wickets fell too. The No3 came and went without living up to the reputation I’d given him. But their No4 made a quick-fire 30 and they finished on a respectable 98 in their 20 overs. Meanwhile, our two occasional spinners recorded their best figures of the season.

Why do we play cricket?

Read more

Half the match had passed and while I hadn’t been actively trying to lose, nor had I been trying to win. I was giving players opportunities they didn’t always get and they were enjoying it. My competitive instinct would typically have returned now, with a total to chase, but I looked around at my team and I saw various players yet to make a decent score this season. This could be the day they did so, if the opposition’s bowling was anything like their batting. And so I put two of our tail-enders at 3 and 4.

Both were clean bowled, making five runs between them, but our spin duo played their best innings of the summer, taking us from 30 for 3 after nine overs to a position where we needed 24 from the last 18 balls. Our youngest batsman, the teenage son of one of our players, hit a few boundaries but couldn’t get the four needed from the last delivery. And so we lost. It felt strange losing like that to a weaker side but I felt we had salvaged something from what could have otherwise been an awful day’s cricket.

Even supposing the captain succeeds in getting 11 players on the field, against that ideal opposition, there still remain infinite ways in which things can go wrong. At least one player will get lost driving to an away game – and home matches are no better, since those who turn up early have to prepare the ground, put out boundary flags and sightscreens. Another player will have forgotten his whites. And pity the skipper who discovered that his first slip had taken ecstasy during the tea interval. Brearley never had to deal with that either.

Sunday, 4 August 2013

On Walking - Advice for a Fifteen Year Old

By Girish Menon

Only the other day at the Bedford cricket festival, Om, our

fifteen year old cricket playing son, asked me for advice on what he should do

if he nicked the ball and the umpire failed to detect it. Apparently, another

player whose father had told him to walk had failed to do so and was afraid of

the consequences if his father became aware of this code violation. At the time

I told Om that it was his decision and I did

not have any clear position in this matter. Hence this piece aims to provide Om with the various nuances involved in this matter. Unfortunately

it may not act as a commandment, 'Thou shall always walk', but it may enable

him to appreciate the diverse viewpoints on this matter.

In some quarters, particularly English, the act of playing

cricket, like doing ethical business, has connotations with a moral code of

behaviour. Every time a batsman, the most recent being Broad, fails to walk the

moralists create a crescendo of condemnation and ridicule. In my opinion this

morality is as fake as Niall Ferguson's claims on 'benevolent and enlightened

imperialism'. Historically, the game of cricket has been played by scoundrels

and saints alike and cheating at cricket has been rife since the time of the

first batting superstar W G Grace.

-----------

Also Read

Also Read

Cricket and DRS - The Best is not the Enemy of the Good

Sreesanth - Another modern day Valmiki?

-----------

Another theory suggests that the moral code for cricket was

invented after World War II by English amateurs to differentiate them from the

professionals who played the game for a living. This period also featured different

dressing rooms for amateurs and professionals, there may also have been a third

dressing room for coloured players. One could therefore surmise that 'walking'

was a code of behaviour for white upper class amateurs who played the game for

pleasure and did not have to bother about their livelihood.

This then raises the question should a professional

cricketer walk?

Honore de Balzac once wrote, 'Behind every great fortune

there is a crime'. Though I am not familiar of the context in which Balzac

penned these words, I assume that he may have referred to the great wealth

accumulated by the businessmen of his times. As a student and a teacher of

economics I am of the conviction that at some stage in their evolution even the

most ethical of businesses and governments may have done things that was not

considered 'cricket'. The British during the empire building period was not

ethical nor have been the Ambanis or Richard Branson.

So if I am the professional batsman, with no other tradable

skill in a market economy with no welfare protection, travelling in a last

chance saloon provided by a whimsical selection committee what would I do? I

would definitely not walk, I'd think it was a divine intervention and try to

play a career saving knock.

As you will see I am a sceptic whenever any government or

business claims that it is always ethical just as much as the claims of walking

by a Gilchrist or a Cowdrey.

I am more sympathetic to the Australian position that it is

the umpire's job to decide if a batsman is out. Since dissent against umpiring

decisions is not tolerated and there is no DRS at the lower echelons of cricket

it does not make sense to walk at all. As for the old chestnut, 'It evens out

in the end', trotted out by wizened

greats of the game I'd like to counter with an ancient Roman story about

drowned worshippers narrated by NN Taleb in his book The Black Swan.

One Diagoras, a non

believer in the gods, was shown painted tablets bearing the portraits of some

worshippers who prayed, then survived a subsequent ship wreck. The implication

was that praying protects you from drowning. Diagoras asked, 'Where were the

pictures of those who prayed, then drowned?"

In a similar vein I wish to ask, 'Where are the batters who

walked and found themselves out of the team?' The problem with the quote, 'It

evens out in the end' is that it is used only by batters who survived. The

views of those batters with good skills but who were not blessed with good

fortune is ignored by this 'half-truth'.

So, Om , to help you make up

your mind I think Kipling's IF says it best:

If you can trust

yourself when all men doubt you

If you can meet with

Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two

impostors just the same

If you can make one

heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one

turn of pitch and toss

And lose, and start

again at your beginnings

Then, you may WALK, my

son! WALK!

There is another advantage, if you can create in the public

eye an 'image' of an honest and upright cricketer. Unlike ordinary mortals, you will find it

easier, in your post cricket life, to garner support as a politician or as an entrepreneur. The gullible public, who make decisions based on media created images, will cling to your past image as an honest cricketer and will back

you with their votes and money. Then what you do with it is really up to you. Just

watch Imran Khan and his crusade for religion and morality!

The writer plays for CamKerala CC in the Cambs league.

The writer plays for CamKerala CC in the Cambs league.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)