No cricket captain needs an ECB survey to tell him what he already knows – that playing numbers in England are in decline. The last game of the season is always the most important one for the amateur skipper. By then, up to half of your players will be deciding whether to play next year, whether they’ll put up with the aches, strains and strife that a full summer of cricket brings. But a decent team performance can erase untold painful memories from earlier in the season and a good individual one will banish all winter’s doubts. You just have to coax enough runs or wickets from those players to ensure you have a full team next year.

This is not a problem that the professional captain faces. Those at the pinnacle of the game can choose from the country’s 844,000 active cricketers – though realistically only the last 4,000 are in the running. The remaining 840,000 of us are making up the numbers. And despite these numbers, many amateur captains will struggle to put out a full XI every weekend. Mike Brearley’s The Art of Captaincy brilliantly describes the challenges that he faced on the cricket field when leading England to Ashes glory in 1981. But he never had to play with nine men.

That is just one of the problems the amateur captain faces. It is perfectly normal for players to drop out on the eve or morning of a game. If this happens in Saturday league cricket, the first team takes the seconds’ star all-rounder but will bat him at 10 and won’t bowl him. The seconds will plunder the thirds for their best batsman and probably won’t give him back. The thirds will reluctantly borrow someone from the fourths, hoping he won’t let them down too much. And the fourths will be short, again, and may have to find something else to do that afternoon.

But league cricket is a distant relation to the professional game. And Sunday cricket is something entirely separate again, and requires a different mindset. This version of the game, perfected over centuries in villages all round England, is the beating heart of cricket. It’s where players are born and die: where once-good cricketers are put out to pasture, fathers and sons play together and where the unselectable finally get a game.

As amateur captain you hope to keep all your players happy. Some will be competent cricketers, others won’t and at least one will not have played before. But you have to forge a team out of them. At this lower level of cricket you try to involve everyone in the game one way or another. Ideally you will have a pair of good batsmen, a competent keeper and a couple of decent bowlers. Hopefully they won’t be the same two people. Then it’s like a game of chess, in which you match up your strong pieces against the opposition’s queen and rooks, and let the pawns fight it out.

Not only do you have to husband your resources carefully, but you won’t always be playing to win. Match-fixing – or match management as we prefer to call it – may be the scourge of the professional game, but it is a key aspect of Sunday cricket and perhaps the only thing that amateurs do better than the professionals.

Although not every captain adheres to these principles, usually both sides want a good close game. A one-sided match is enjoyable for the dominant players, but when the outcome is so predictable, the rest lose heart and interest. They all know how the story ends and that they’re not the hero. So sometimes it pays to take the pressure off for an over or two and let the opposition regroup. After all, you don’t want the game to be over by tea.

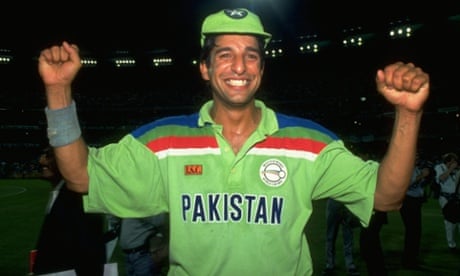

How I came to own the sweater Wasim Akram wore at the 1992 World Cup final

Read more

There are various ways of doing this but, however you do it, discretion is key – just as it was for Hansie Cronje or Salman Butt. You shouldn’t be asking anyone to underperform, nor be doing so yourself. I’ve never deliberately bowled a full toss, wide or no-ball – there are many better ways to alter the balance of a game. You give a weaker bowler a couple of overs too many, with an attacking field. Your cannier teammates may guess what’s going on, but the rest won’t. They’ll be too busy thinking about their own game.

But this tends to happen after the opposition has lost five quick wickets and is a hundred runs short of a competitive total. What is rare is having to match manage from the outset. It has only happened to me once. I captain a team of writers and we tend to play teams that are a little bit stronger than us. After all, authorship usually comes in the later decades of life, and consequently, our squad is long on experience but short on speed and agility.

This particular day we were playing a team of a similar vintage. I walked out with their captain for the toss and we had the standard conversation about the respective strengths of our teams, and agreed a 20-over format. One of cricket’s great joys is that things are not always what they seem. I’ve seen septuagenarians bowl maiden after maiden, morbidly obese batsmen strike quick fifties, and small children throw the stumps down from 30 yards. But as I looked at the opposition, I was pretty sure that appearances didn’t mislead and that we were the stronger side. I called correctly and put them in, thinking that it would be easier to control the game that way. We had a decent team, with enough bowling and batting to cruise to a sporting win.

I was already fretting after just two overs. Their score stood at two for no loss as the openers took a circumspect approach to batting. Chris Gayle often plays out a maiden before unleashing hell in the next over. But these two played more like Chris Tavaré and showed no signs of wanting to accelerate. At this rate we would be lucky to be chasing more than 50.

After four overs, I turned to spin, telling the surprised new bowler that I was keeping myself back for their No3, whom I knew to be their best player. (At our level, few spinners hit the stumps regularly. Each ball comes out of the hand differently. Then there’s the variation the bowler feels it necessary to add, having zealously watched clips of Warne in action. The result is always six very different deliveries, which will include a full toss, a wide and one that bounces twice. It is almost impossible not to score at least five an over off a bowler such as this, particularly if the field includes two slips and a couple of gullies as mine did. Full tosses can be hit to fielders and double bouncers sometimes pass under the bat onto the stumps.) And so the opposition’s score crept up but the wickets fell too. The No3 came and went without living up to the reputation I’d given him. But their No4 made a quick-fire 30 and they finished on a respectable 98 in their 20 overs. Meanwhile, our two occasional spinners recorded their best figures of the season.

Why do we play cricket?

Read more

Half the match had passed and while I hadn’t been actively trying to lose, nor had I been trying to win. I was giving players opportunities they didn’t always get and they were enjoying it. My competitive instinct would typically have returned now, with a total to chase, but I looked around at my team and I saw various players yet to make a decent score this season. This could be the day they did so, if the opposition’s bowling was anything like their batting. And so I put two of our tail-enders at 3 and 4.

Both were clean bowled, making five runs between them, but our spin duo played their best innings of the summer, taking us from 30 for 3 after nine overs to a position where we needed 24 from the last 18 balls. Our youngest batsman, the teenage son of one of our players, hit a few boundaries but couldn’t get the four needed from the last delivery. And so we lost. It felt strange losing like that to a weaker side but I felt we had salvaged something from what could have otherwise been an awful day’s cricket.

Even supposing the captain succeeds in getting 11 players on the field, against that ideal opposition, there still remain infinite ways in which things can go wrong. At least one player will get lost driving to an away game – and home matches are no better, since those who turn up early have to prepare the ground, put out boundary flags and sightscreens. Another player will have forgotten his whites. And pity the skipper who discovered that his first slip had taken ecstasy during the tea interval. Brearley never had to deal with that either.

No comments:

Post a Comment