Brad Haddin in Cricinfo

Wind the clock back to March 2013. I'm boarding a flight home from India with Michael Clarke. He's out of the final Test of that series in Delhi with a back flare-up, while I'm travelling home after being the injury replacement for Matthew Wade in Mohali.

Plenty has gone on in the preceding week or so, the "homework"-related suspensions of Shane Watson, Mitchell Johnson, Usman Khawaja and James Pattinson in particular. So we take the opportunity to speak pretty openly about how the team is functioning, and how unhappy everyone is with the way the Indian tour has panned out, in the way some players have been treated and the mood around the team.

For one thing, expectations of behaviour seem to be driven by management rather than players, and that's something that needs to change.

Mickey Arthur is yet to be replaced by Darren Lehmann, but it's an important conversation in terms of how Michael thinks the team should operate in the coming months. It helps too that having been away from the team for a while, I can see things from an angle Michael isn't seeing. One change in the interim is the much more experienced side chosen for the Ashes tour that follows.

While I did not officially hold the title at the time, that's a good example of how a deputy should operate. Vice-captaincy is a low-profile job that's not fully understood by many, but it is vital to helping get a successful team moving in the right direction together. One bedrock of the gig is to have a deputy committed to that role, rather than thinking about being captain himself. That was certainly the case with me.

The other foundation of the job is a relationship with the captain that allows you to speak frankly with him about where the team is going - in private rather than in front of the team. Keeping an ear to the ground and communicating with other players and then relaying that to the leader when necessary. Having gone back a long way with Michael, we had that sort of dynamic.

These conversations should be honest enough to be able to say, "I don't think this is working, and this is how the group is feeling", or "I think you might have missed this". These aren't always the easiest conversations, but they have to happen from a place of mutual respect. The captain can either take note or disregard it, but the main thing is that he knows how things are tracking when he does make his final call on a given issue. That doesn't happen without a healthy relationship between captain and deputy.

Overall, the role of the vice-captain is to complement what the captain does. Your job is to make sure the younger guys are feeling a part of the team and that they understand the standards that you want to set in the group and that your behaviour is not to be compromised.

You pick up on the little things around the team, like being punctual, wearing the right uniforms and treating people inside and outside the team with respect, and have a quiet word to guys here and there if they need a reminder. That then flows into attention to detail in the middle.

Michael was a very good tactical captain who was always in control on the field. My job, relative to him - and similarly for other senior players - was to make sure the mood of the team was right, and to set standards for the younger guys to follow; to be sure they knew what it meant to be an Australian cricketer. The vice-captain should be the guy to drive that.

Once we got to England in 2013, I took it upon myself to spend time with each player to talk about the brand of cricket we wanted to play and also to make sure guys were talking and reflecting on the game and each other, whether we'd had a good day or a bad day.

We did that after a close loss in the first Test at Trent Bridge and that was a good moment - we weren't retreating into ourselves in defeat. Once again, that flowed well into the success we had later, because guys were talking and enjoying each other's good days, having commiserated through the bad ones.

For a long time in cricket, I think that sort of thing happened pretty organically. But in an era when the game is so professionalised and guys are jetting around playing T20 tournaments when not with Australia or even their domestic teams, it takes thoughtful effort to make sure it still happens. If anything, vice-captaincy has grown in importance for that reason.

I mentioned earlier that one key to the job is not wanting the captaincy. If you look back through the recent history of Australian cricket, the examples are plentiful. Geoff Marsh was a terrific lieutenant to Allan Border, Ian Healy to Mark Taylor, and Adam Gilchrist to Ricky Ponting.

Once we got to England in 2013, I took it upon myself to spend time with each player to talk about the brand of cricket we wanted to play

They are three contrasting characters, but what they had in common was no great desire to be captain. I saw Gilly's work up close as a junior member of the squad, and he was a terrific link man between the leadership and the team. As fellow glovemen, I also saw how the role behind the stumps gave you a great perspective to support the captain.

There have been other times, of course, when the vice-captain is the heir-apparent. That was the case for Taylor, when he was deputy to AB, for Steve Waugh, when he replaced Heals as vice-captain to Taylor, and for Michael, when he was appointed deputy to Ricky after Gilly retired. All those guys will tell you that it put them in awkward positions at times, not knowing whether to intervene in things or not, whether on or off the field.

Similarly, Watson had a difficult time as Michael's deputy because they did not have the same open relationship to discuss things that I was fortunate enough to have. That's something for Cricket Australia to keep in mind whenever it makes these appointments.

Right now, Steven Smith has an able deputy in David Warner. To me, this relationship should work because, like Michael and I, these two have known each other for years. Davey is growing into the role at present, evolving from his former "attack dog" persona into someone more measured. If he ever wants a reminder of how vice-captaincy should or shouldn't work, he needs only to think back to a year like 2013 and the team's contrasting fortunes.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label vice. Show all posts

Showing posts with label vice. Show all posts

Tuesday, 25 October 2016

Monday, 23 February 2015

The bishops’ letter to British politicians is a true act of leadership

Jon Cruddas in The Guardian

I welcome the pastoral letter by the bishops of the Church of England at many levels.

It expresses concern about the condition of our country and its public institutions, so it is by definition political; but it is not party political – and is all the better for it. It is as much a challenge to the left, and our commitment to the state and centralisation, as it is to the right with its unquestioning embrace of the market. Its roots are far deeper than 20th-century ideologies, drawing upon Aristotle and Catholic social thought every bit as much as the English commonwealth tradition of federal democracy.

It is a profound, complex letter, as brutal as it is tender, as Catholic as it is reformed, as conservative as it is radical. It draws upon ideas of virtue and vocation in the economy that are out of fashion, but necessary for our country as we defend ourselves from a repetition of the vices that led to the financial crash and its subsequent debt and deficit. It invites us to move away from grievance, disenchantment and blame, and towards the pursuit of the common good.

It cannot be the case that any criticism of capitalism is received as leftwing Keynesian welfarism, and any public sector reform as an attack on the poor. This is precisely what the letter warns against, and it is a dismal reality of our public conversation that it has been received in that way.

I also welcome the letter as a profound contribution by the church to the political life of our nation. Christianity and the church have always been part of that story. Not as a dominant voice, but bringing an important perspective from an ancient institution that is present in every part of our country as a witness and participant. From the introduction of a legal order and the development of education, the church has been part of our body politic, so it is incorrect to say that the church should stay out of politics: it is morally committed to participation and democracy as a means, and the common good as the end.

One of the great things about faith traditions is that they do not think that the free market created the world. They have a concept of a person that is neither just a commodity nor an administrative unit, but a relational being capable of power and responsibility and of living with others in civic peace and prosperity. They also do not view the natural environment as a commodity, but an inheritance that requires careful stewardship. Conservatives and socialists have shared these assumptions and they could be the basis of a new consensus.

The bishops have said that the two big postwar political dreams – the collectivism of 1945 with its nationalisation and centralised universal welfare state, and the1979 dream of a free-market revolution – have both failed and we need to develop an alternative vision. As we know, 1997 was not the answer either. The financial markets and the administrative state are too strong and society is too weak. The bishops are right to say that the “big society” was a good idea that dissolved into an aspiration, by turns pious and cynical. The answer is not to return to the old certainties, but to ask why things failed and how society could be made stronger. I think that Labour’s policy review has made a strong start in this direction.

The letter has a lot of interesting things to say about character and virtue and how these are best supported in human-scale institutions; how the family is a school of love and sacrifice, and how we can support relationships in a world that encourages immediate gratification and is in danger of losing the precious art of negotiation and accommodation. There is not enough love in the economic or political system, and the bishops are right to bring this to our attention.

In another expression of the generosity of thought in this letter, the lead taken by Pope Francis in addressing economic issues has been embraced. When the banks are borrowing at 2% and lending to payday lenders at 7%, which lend to the poor at 5,500%, the bishops are right to call this usury and to say that it is wrong. They are also right to say that there needs to be a decentralisation of economic as well as political power. They are right to say that there are incentives to vice when there should be incentives to virtue. They are right to say that work is a noble calling, that good work generates value, and that workers should be treated with dignity. They are right to value work and support a living wage, and to build up credit unions as an alternative to payday lenders.

They are also right to point out that competition is opposed to monopoly and not cooperation, which is necessary for a successful economy: an isolated individual can never become an autonomous person. They are also right to remind us of the importance of place and to warn us against a carelessness to its wellbeing.

That is why decentralisation and subsidiarity are vital for our country, so that we do not become a society of strangers, but can build bonds of solidarity and mutual obligation.

Above all, the bishops are right to assert that autonomous self-governing institutions that mediate between the state and the market are a vital part of our national renewal. The BBC, our great universities and schools, city governments and the church are our civic inheritance, and vital to the wellbeing of the nation. All are threatened by the centralised control of the market and state. We cannot do this alone, and that is why politics – doing things together – is important; and that is why the body politic and not just the state is important. Our cities and towns cannot take responsibility unless they have power.

As the election approaches there will be a tendency to turn everything into a party political conflict. That is understandable, but there is also a place for us to engage in a longer-term conversation, a covenantal conversation, about how we renew our inheritance and rise to the challenge of living together for the good.

I have read the letter and learned a great deal from it. I will read it again and reflect on its teaching because the issues it raises will endure beyond May.

Issues of how to build a common life under conditions of pluralism, how to engage people in political participation and self-government, how to decentralise political and economic power, how to resist the domination of the rich and the powerful, how to renew love and work so that life can be meaningful and fulfilling. These are the right questions to be asking.

I am grateful to the bishops for challenging us to develop a better and more generous politics and public conversation. It is an act of leadership.

I welcome the pastoral letter by the bishops of the Church of England at many levels.

It expresses concern about the condition of our country and its public institutions, so it is by definition political; but it is not party political – and is all the better for it. It is as much a challenge to the left, and our commitment to the state and centralisation, as it is to the right with its unquestioning embrace of the market. Its roots are far deeper than 20th-century ideologies, drawing upon Aristotle and Catholic social thought every bit as much as the English commonwealth tradition of federal democracy.

It is a profound, complex letter, as brutal as it is tender, as Catholic as it is reformed, as conservative as it is radical. It draws upon ideas of virtue and vocation in the economy that are out of fashion, but necessary for our country as we defend ourselves from a repetition of the vices that led to the financial crash and its subsequent debt and deficit. It invites us to move away from grievance, disenchantment and blame, and towards the pursuit of the common good.

It cannot be the case that any criticism of capitalism is received as leftwing Keynesian welfarism, and any public sector reform as an attack on the poor. This is precisely what the letter warns against, and it is a dismal reality of our public conversation that it has been received in that way.

I also welcome the letter as a profound contribution by the church to the political life of our nation. Christianity and the church have always been part of that story. Not as a dominant voice, but bringing an important perspective from an ancient institution that is present in every part of our country as a witness and participant. From the introduction of a legal order and the development of education, the church has been part of our body politic, so it is incorrect to say that the church should stay out of politics: it is morally committed to participation and democracy as a means, and the common good as the end.

One of the great things about faith traditions is that they do not think that the free market created the world. They have a concept of a person that is neither just a commodity nor an administrative unit, but a relational being capable of power and responsibility and of living with others in civic peace and prosperity. They also do not view the natural environment as a commodity, but an inheritance that requires careful stewardship. Conservatives and socialists have shared these assumptions and they could be the basis of a new consensus.

The bishops have said that the two big postwar political dreams – the collectivism of 1945 with its nationalisation and centralised universal welfare state, and the1979 dream of a free-market revolution – have both failed and we need to develop an alternative vision. As we know, 1997 was not the answer either. The financial markets and the administrative state are too strong and society is too weak. The bishops are right to say that the “big society” was a good idea that dissolved into an aspiration, by turns pious and cynical. The answer is not to return to the old certainties, but to ask why things failed and how society could be made stronger. I think that Labour’s policy review has made a strong start in this direction.

The letter has a lot of interesting things to say about character and virtue and how these are best supported in human-scale institutions; how the family is a school of love and sacrifice, and how we can support relationships in a world that encourages immediate gratification and is in danger of losing the precious art of negotiation and accommodation. There is not enough love in the economic or political system, and the bishops are right to bring this to our attention.

In another expression of the generosity of thought in this letter, the lead taken by Pope Francis in addressing economic issues has been embraced. When the banks are borrowing at 2% and lending to payday lenders at 7%, which lend to the poor at 5,500%, the bishops are right to call this usury and to say that it is wrong. They are also right to say that there needs to be a decentralisation of economic as well as political power. They are right to say that there are incentives to vice when there should be incentives to virtue. They are right to say that work is a noble calling, that good work generates value, and that workers should be treated with dignity. They are right to value work and support a living wage, and to build up credit unions as an alternative to payday lenders.

They are also right to point out that competition is opposed to monopoly and not cooperation, which is necessary for a successful economy: an isolated individual can never become an autonomous person. They are also right to remind us of the importance of place and to warn us against a carelessness to its wellbeing.

That is why decentralisation and subsidiarity are vital for our country, so that we do not become a society of strangers, but can build bonds of solidarity and mutual obligation.

Above all, the bishops are right to assert that autonomous self-governing institutions that mediate between the state and the market are a vital part of our national renewal. The BBC, our great universities and schools, city governments and the church are our civic inheritance, and vital to the wellbeing of the nation. All are threatened by the centralised control of the market and state. We cannot do this alone, and that is why politics – doing things together – is important; and that is why the body politic and not just the state is important. Our cities and towns cannot take responsibility unless they have power.

As the election approaches there will be a tendency to turn everything into a party political conflict. That is understandable, but there is also a place for us to engage in a longer-term conversation, a covenantal conversation, about how we renew our inheritance and rise to the challenge of living together for the good.

I have read the letter and learned a great deal from it. I will read it again and reflect on its teaching because the issues it raises will endure beyond May.

Issues of how to build a common life under conditions of pluralism, how to engage people in political participation and self-government, how to decentralise political and economic power, how to resist the domination of the rich and the powerful, how to renew love and work so that life can be meaningful and fulfilling. These are the right questions to be asking.

I am grateful to the bishops for challenging us to develop a better and more generous politics and public conversation. It is an act of leadership.

Wednesday, 2 October 2013

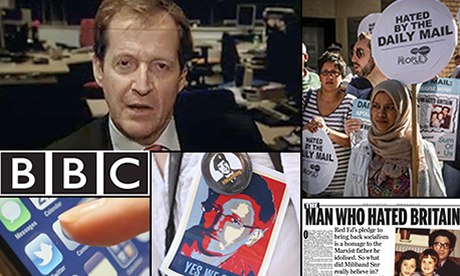

Alastair Campbell's attack on the Mail was terrifying – and brilliant

Why is the left obsessed by the Daily Mail?

The Guardian has published an extensive critique of the Daily Mail and its reporting of Labour, press regulation and the Snowden leaks. We invited Mail readers to join in that debate. Paul Dacre, editor-in-chief, asked for the opportunity to comment. Here is his contribution

Paul Dacre: 'Our crime is that the Mail constantly dares to stand up to the liberal-left consensus that dominates so many areas of British life.' Montage: Guardian

Out in the real world, it was a pretty serious week for news. The US was on the brink of budget default, a British court heard how for two years social workers failed to detect the mummified body of a four-year-old starved to death by his mother, and it was claimed that the then Labour health secretary had covered up unnecessary deaths in a NHS hospital six months before the election.

In contrast, the phoney world of Twitter, the London chatterati and left-wing media was gripped 10 days ago by collective hysteria as it became obsessed round-the-clock by one story – a five-word headline on page 16 in the Daily Mail.

The screech of axe-grinding was deafening as the paper's enemies gleefully leapt to settle scores.

Leading the charge, inevitably, was the Mail's bête noir, the BBC. Fair-minded readers will decide themselves whether the hundreds of hours of airtime it devoted to that headline reveal a disturbing lack of journalistic proportionality and impartiality – but certainly the one-sided tone in their reporting allowed Labour to misrepresent Geoffrey Levy's article on Ralph Miliband.

The genesis of that piece lay in Ed Miliband's conference speech. The Mail was deeply concerned that in 2013, after all the failures of socialism in the twentieth century, the leader of the Labour party was announcing its return, complete with land seizures and price fixing.

Surely, we reasoned, the public had the right to know what influence the Labour leader's Marxist father, to whom he constantly referred in his speeches, had on his thinking.

So it was that Levy's article examined the views held by Miliband senior over his lifetime, not just as a 17-year-old youth as has been alleged by our critics.

The picture that emerged was of a man who gave unqualified support to Russian totalitarianism until the mid-50s, who loathed the market economy, was in favour of a workers' revolution, denigrated British traditions and institutions such as the royal family, the church and the army and was overtly dismissive of western democracy.

Levy's article argued that the Marxism that inspired Ralph Miliband had provided the philosophical underpinning of one of history's most appalling regimes – a regime, incidentally, that totally crushed freedom of expression.

Nowhere did the Mail suggest that Ralph Miliband was evil – only that the political beliefs he espoused had resulted in evil. As for the headline "The Man Who Hated Britain", our point was simply this: Ralph Miliband was, as a Marxist, committed to smashing the institutions that make Britain distinctively British – and, with them, the liberties and democracy those institutions have fostered.

Yes, the Mail is happy to accept that in his personal life, Ralph Miliband was, as described by his son, a decent and kindly man – although we won't withdraw our view that he supported an ideology that caused untold misery in the world.

Yes, we accept that he cherished this country's traditions of tolerance and freedom – while, in a troubling paradox typical of the left, detesting the very institutions and political system that made those traditions possible.

And yes, the headline was controversial – but popular newspapers have a long tradition of using provocative headlines to grab readers' attention. In isolation that headline may indeed seem over the top, but read in conjunction with the article we believed it was justifiable.

Despite this we acceded to Mr Miliband's demand – and by golly, he did demand – that we publish his 1,000-word article defending his father.

So it was that, in a virtually unprecedented move, we published his words at the top of our op ed pages. They were accompanied by an abridged version of the original Levy article and a leader explaining why the Mail wasn't apologising for the points it made.

The hysteria that followed is symptomatic of the post-Leveson age in which any newspaper which dares to take on the left in the interests of its readers risks being howled down by the Twitter mob who the BBC absurdly thinks represent the views of real Britain.

As the week progressed and the hysteria increased, it became clear that this was no longer a story about an article on Mr Miliband's Marxist father but a full-scale war by the BBC and the left against the paper that is their most vocal critic.

Orchestrating this bile was an ever more rabid Alastair Campbell. Again, fair-minded readers will wonder why a man who helped drive Dr David Kelly to his death, was behind the dodgy Iraq war dossier and has done more to poison the well of public discourse than anyone in Britain is given so much air-time by the BBC.

But the BBC's blood lust was certainly up. Impartiality flew out of the window. Ancient feuds were settled. Not to put too fine a point on things, we were right royally turned over.

Fair enough, if you dish it out, you take it. But my worry is that there was a more disturbing agenda to last week's events.

Mr Miliband, of course, exults in being the man who destroyed Murdoch in this country. Is it fanciful to believe that his real purpose in triggering last week's row – so assiduously supported by the liberal media which sneers at the popular press – was an attempt to neutralise Associated, the Mail's publishers and one of Britain's most robustly independent and successful newspaper groups.

Let it be said loud and clear that the Mail, unlike News International, did NOT hack people's phones or pay the police for stories. I have sworn that on oath.

No, our crime is more heinous than that.

It is that the Mail constantly dares to stand up to the liberal-left consensus that dominates so many areas of British life and instead represents the views of the ordinary people who are our readers and who don't have a voice in today's political landscape and are too often ignored by today's ruling elite.

The metropolitan classes, of course, despise our readers with their dreams (mostly unfulfilled) of a decent education and health service they can trust, their belief in the family, patriotism, self-reliance, and their over-riding suspicion of the state and the People Who Know Best.

These people mock our readers' scepticism over the European Union and a human rights court that seems to care more about the criminal than the victim. They scoff at our readers who, while tolerant, fret that the country's schools and hospitals can't cope with mass immigration.

In other words, these people sneer at the decent working Britons – I'd argue they are the backbone of this country – they constantly profess to be concerned about.

The truth is that there is an unpleasant intellectual snobbery about the Mail in leftish circles, for whom the word 'suburban' is an obscenity. They simply cannot comprehend how a paper that opposes the mindset they hold dear can be so successful and so loved by its millions of readers.

Well, I'm proud that the Mail stands up for those readers.

I am proud that our Dignity For The Elderly Campaign has for years stood up for Britain's most neglected community. Proud that we have fought for justice for Stephen Lawrence, Gary McKinnon and the relatives of the victims of the Omagh bombing, for those who have seen loved ones suffer because of MRSA and the Liverpool Care Pathway. I am proud that we have led great popular campaigns for the NSPCC and Alzheimer's Society on the dangers of paedophilia and the agonies of dementia. And I'm proud of our war against round-the-clock drinking, casinos, plastic bags, internet pornography and secret courts.

No other newspaper campaigns as vigorously as the Mail and I am proud of the ability of the paper's 400 journalists (the BBC has 8,000) to continually set the national agenda on a whole host of issues.

I am proud that for years, while most of Fleet Street were in thrall to it, the Mail was the only paper to stand up to the malign propaganda machine of Tony Blair and his appalling henchman, Campbell (and, my goodness, it's been payback time over the past week!).

Could all these factors also be behind the left's tsunami of opprobrium against the Mail last week? I don't know but I do know that for a party mired in the corruption exposed by Damian McBride's book (in which Ed Miliband was a central player) to call for a review of the Mail's practices and culture is beyond satire.

Certainly, the Mail will not be silenced by a Labour party that has covered up unnecessary, and often horrific, deaths in NHS hospitals, and suggests instead that it should start looking urgently at its own culture and practices.

Some have argued that last week's brouhaha shows the need for statutory press regulation. I would argue the opposite. The febrile heat, hatred, irrationality and prejudice provoked by last week's row reveals why politicians must not be allowed anywhere near press regulation.

And while the Mail does not agree with the Guardian over the stolen secret security files it published, I suggest that we can agree that the fury and recrimination the story is provoking reveals again why those who rule us – and who should be held to account by newspapers – cannot be allowed to sit in judgment on the press.

That is why the left should be very careful about what it wishes for – especially in the light of this week's rejection by the politicians of the newspaper industry's charter for robust independent self-regulation.

The BBC is controlled, through the licence fee, by the politicians. ITV has to answer to Ofcom, a government quango. Newspapers are the only mass media left in Britain free from the control of the state.

The Mail has recognised the hurt Mr Miliband felt over our attack on his father's beliefs. We were happy to give him considerable space to describe how his father had fought for Britain (though a man who so smoothly diddled his brother risks laying himself open to charges of cynicism if he makes too much of a fanfare over familial loyalties).

For the record, the Mail received a mere two letters of complaint before Mr Miliband's intervention and only a few hundred letters and emails since – many in support. A weekend demonstration against the paper attracted just 110 people.

It seems that in the real world people – most of all our readers – were far more supportive of us than the chatterati would have you believe.

PS – this week the head of MI5 – subsequently backed by the PM, the deputy PM, the home secretary and Labour's elder statesman Jack Straw – effectively accused the Guardian of aiding terrorism by publishing stolen secret security files. The story – which is of huge significance – was given scant coverage by a BBC which only a week ago had devoted days of wall-to-wall pejorative coverage to the Mail. Again, I ask fair readers, what is worse: to criticise the views of a Marxist thinker, whose ideology is anathema to most and who had huge influence on the man who could one day control our security forces … or to put British lives at risk by helping terrorists?

Paul Dacre: 'Our crime is that the Mail constantly dares to stand up to the liberal-left consensus that dominates so many areas of British life.' Montage: Guardian

Out in the real world, it was a pretty serious week for news. The US was on the brink of budget default, a British court heard how for two years social workers failed to detect the mummified body of a four-year-old starved to death by his mother, and it was claimed that the then Labour health secretary had covered up unnecessary deaths in a NHS hospital six months before the election.

In contrast, the phoney world of Twitter, the London chatterati and left-wing media was gripped 10 days ago by collective hysteria as it became obsessed round-the-clock by one story – a five-word headline on page 16 in the Daily Mail.

The screech of axe-grinding was deafening as the paper's enemies gleefully leapt to settle scores.

Leading the charge, inevitably, was the Mail's bête noir, the BBC. Fair-minded readers will decide themselves whether the hundreds of hours of airtime it devoted to that headline reveal a disturbing lack of journalistic proportionality and impartiality – but certainly the one-sided tone in their reporting allowed Labour to misrepresent Geoffrey Levy's article on Ralph Miliband.

The genesis of that piece lay in Ed Miliband's conference speech. The Mail was deeply concerned that in 2013, after all the failures of socialism in the twentieth century, the leader of the Labour party was announcing its return, complete with land seizures and price fixing.

Surely, we reasoned, the public had the right to know what influence the Labour leader's Marxist father, to whom he constantly referred in his speeches, had on his thinking.

So it was that Levy's article examined the views held by Miliband senior over his lifetime, not just as a 17-year-old youth as has been alleged by our critics.

The picture that emerged was of a man who gave unqualified support to Russian totalitarianism until the mid-50s, who loathed the market economy, was in favour of a workers' revolution, denigrated British traditions and institutions such as the royal family, the church and the army and was overtly dismissive of western democracy.

Levy's article argued that the Marxism that inspired Ralph Miliband had provided the philosophical underpinning of one of history's most appalling regimes – a regime, incidentally, that totally crushed freedom of expression.

Nowhere did the Mail suggest that Ralph Miliband was evil – only that the political beliefs he espoused had resulted in evil. As for the headline "The Man Who Hated Britain", our point was simply this: Ralph Miliband was, as a Marxist, committed to smashing the institutions that make Britain distinctively British – and, with them, the liberties and democracy those institutions have fostered.

Yes, the Mail is happy to accept that in his personal life, Ralph Miliband was, as described by his son, a decent and kindly man – although we won't withdraw our view that he supported an ideology that caused untold misery in the world.

Yes, we accept that he cherished this country's traditions of tolerance and freedom – while, in a troubling paradox typical of the left, detesting the very institutions and political system that made those traditions possible.

And yes, the headline was controversial – but popular newspapers have a long tradition of using provocative headlines to grab readers' attention. In isolation that headline may indeed seem over the top, but read in conjunction with the article we believed it was justifiable.

Despite this we acceded to Mr Miliband's demand – and by golly, he did demand – that we publish his 1,000-word article defending his father.

So it was that, in a virtually unprecedented move, we published his words at the top of our op ed pages. They were accompanied by an abridged version of the original Levy article and a leader explaining why the Mail wasn't apologising for the points it made.

The hysteria that followed is symptomatic of the post-Leveson age in which any newspaper which dares to take on the left in the interests of its readers risks being howled down by the Twitter mob who the BBC absurdly thinks represent the views of real Britain.

As the week progressed and the hysteria increased, it became clear that this was no longer a story about an article on Mr Miliband's Marxist father but a full-scale war by the BBC and the left against the paper that is their most vocal critic.

Orchestrating this bile was an ever more rabid Alastair Campbell. Again, fair-minded readers will wonder why a man who helped drive Dr David Kelly to his death, was behind the dodgy Iraq war dossier and has done more to poison the well of public discourse than anyone in Britain is given so much air-time by the BBC.

But the BBC's blood lust was certainly up. Impartiality flew out of the window. Ancient feuds were settled. Not to put too fine a point on things, we were right royally turned over.

Fair enough, if you dish it out, you take it. But my worry is that there was a more disturbing agenda to last week's events.

Mr Miliband, of course, exults in being the man who destroyed Murdoch in this country. Is it fanciful to believe that his real purpose in triggering last week's row – so assiduously supported by the liberal media which sneers at the popular press – was an attempt to neutralise Associated, the Mail's publishers and one of Britain's most robustly independent and successful newspaper groups.

Let it be said loud and clear that the Mail, unlike News International, did NOT hack people's phones or pay the police for stories. I have sworn that on oath.

No, our crime is more heinous than that.

It is that the Mail constantly dares to stand up to the liberal-left consensus that dominates so many areas of British life and instead represents the views of the ordinary people who are our readers and who don't have a voice in today's political landscape and are too often ignored by today's ruling elite.

The metropolitan classes, of course, despise our readers with their dreams (mostly unfulfilled) of a decent education and health service they can trust, their belief in the family, patriotism, self-reliance, and their over-riding suspicion of the state and the People Who Know Best.

These people mock our readers' scepticism over the European Union and a human rights court that seems to care more about the criminal than the victim. They scoff at our readers who, while tolerant, fret that the country's schools and hospitals can't cope with mass immigration.

In other words, these people sneer at the decent working Britons – I'd argue they are the backbone of this country – they constantly profess to be concerned about.

The truth is that there is an unpleasant intellectual snobbery about the Mail in leftish circles, for whom the word 'suburban' is an obscenity. They simply cannot comprehend how a paper that opposes the mindset they hold dear can be so successful and so loved by its millions of readers.

Well, I'm proud that the Mail stands up for those readers.

I am proud that our Dignity For The Elderly Campaign has for years stood up for Britain's most neglected community. Proud that we have fought for justice for Stephen Lawrence, Gary McKinnon and the relatives of the victims of the Omagh bombing, for those who have seen loved ones suffer because of MRSA and the Liverpool Care Pathway. I am proud that we have led great popular campaigns for the NSPCC and Alzheimer's Society on the dangers of paedophilia and the agonies of dementia. And I'm proud of our war against round-the-clock drinking, casinos, plastic bags, internet pornography and secret courts.

No other newspaper campaigns as vigorously as the Mail and I am proud of the ability of the paper's 400 journalists (the BBC has 8,000) to continually set the national agenda on a whole host of issues.

I am proud that for years, while most of Fleet Street were in thrall to it, the Mail was the only paper to stand up to the malign propaganda machine of Tony Blair and his appalling henchman, Campbell (and, my goodness, it's been payback time over the past week!).

Could all these factors also be behind the left's tsunami of opprobrium against the Mail last week? I don't know but I do know that for a party mired in the corruption exposed by Damian McBride's book (in which Ed Miliband was a central player) to call for a review of the Mail's practices and culture is beyond satire.

Certainly, the Mail will not be silenced by a Labour party that has covered up unnecessary, and often horrific, deaths in NHS hospitals, and suggests instead that it should start looking urgently at its own culture and practices.

Some have argued that last week's brouhaha shows the need for statutory press regulation. I would argue the opposite. The febrile heat, hatred, irrationality and prejudice provoked by last week's row reveals why politicians must not be allowed anywhere near press regulation.

And while the Mail does not agree with the Guardian over the stolen secret security files it published, I suggest that we can agree that the fury and recrimination the story is provoking reveals again why those who rule us – and who should be held to account by newspapers – cannot be allowed to sit in judgment on the press.

That is why the left should be very careful about what it wishes for – especially in the light of this week's rejection by the politicians of the newspaper industry's charter for robust independent self-regulation.

The BBC is controlled, through the licence fee, by the politicians. ITV has to answer to Ofcom, a government quango. Newspapers are the only mass media left in Britain free from the control of the state.

The Mail has recognised the hurt Mr Miliband felt over our attack on his father's beliefs. We were happy to give him considerable space to describe how his father had fought for Britain (though a man who so smoothly diddled his brother risks laying himself open to charges of cynicism if he makes too much of a fanfare over familial loyalties).

For the record, the Mail received a mere two letters of complaint before Mr Miliband's intervention and only a few hundred letters and emails since – many in support. A weekend demonstration against the paper attracted just 110 people.

It seems that in the real world people – most of all our readers – were far more supportive of us than the chatterati would have you believe.

PS – this week the head of MI5 – subsequently backed by the PM, the deputy PM, the home secretary and Labour's elder statesman Jack Straw – effectively accused the Guardian of aiding terrorism by publishing stolen secret security files. The story – which is of huge significance – was given scant coverage by a BBC which only a week ago had devoted days of wall-to-wall pejorative coverage to the Mail. Again, I ask fair readers, what is worse: to criticise the views of a Marxist thinker, whose ideology is anathema to most and who had huge influence on the man who could one day control our security forces … or to put British lives at risk by helping terrorists?

The Guardian has published an extensive critique of the Daily Mail and its reporting of Labour, press regulation and the Snowden leaks. We invited Mail readers to join in that debate. Paul Dacre, editor-in-chief, asked for the opportunity to comment. Here is his contribution

Paul Dacre: 'Our crime is that the Mail constantly dares to stand up to the liberal-left consensus that dominates so many areas of British life.' Montage: Guardian

Out in the real world, it was a pretty serious week for news. The US was on the brink of budget default, a British court heard how for two years social workers failed to detect the mummified body of a four-year-old starved to death by his mother, and it was claimed that the then Labour health secretary had covered up unnecessary deaths in a NHS hospital six months before the election.

In contrast, the phoney world of Twitter, the London chatterati and left-wing media was gripped 10 days ago by collective hysteria as it became obsessed round-the-clock by one story – a five-word headline on page 16 in the Daily Mail.

The screech of axe-grinding was deafening as the paper's enemies gleefully leapt to settle scores.

Leading the charge, inevitably, was the Mail's bête noir, the BBC. Fair-minded readers will decide themselves whether the hundreds of hours of airtime it devoted to that headline reveal a disturbing lack of journalistic proportionality and impartiality – but certainly the one-sided tone in their reporting allowed Labour to misrepresent Geoffrey Levy's article on Ralph Miliband.

The genesis of that piece lay in Ed Miliband's conference speech. The Mail was deeply concerned that in 2013, after all the failures of socialism in the twentieth century, the leader of the Labour party was announcing its return, complete with land seizures and price fixing.

Surely, we reasoned, the public had the right to know what influence the Labour leader's Marxist father, to whom he constantly referred in his speeches, had on his thinking.

So it was that Levy's article examined the views held by Miliband senior over his lifetime, not just as a 17-year-old youth as has been alleged by our critics.

The picture that emerged was of a man who gave unqualified support to Russian totalitarianism until the mid-50s, who loathed the market economy, was in favour of a workers' revolution, denigrated British traditions and institutions such as the royal family, the church and the army and was overtly dismissive of western democracy.

Levy's article argued that the Marxism that inspired Ralph Miliband had provided the philosophical underpinning of one of history's most appalling regimes – a regime, incidentally, that totally crushed freedom of expression.

Nowhere did the Mail suggest that Ralph Miliband was evil – only that the political beliefs he espoused had resulted in evil. As for the headline "The Man Who Hated Britain", our point was simply this: Ralph Miliband was, as a Marxist, committed to smashing the institutions that make Britain distinctively British – and, with them, the liberties and democracy those institutions have fostered.

Yes, the Mail is happy to accept that in his personal life, Ralph Miliband was, as described by his son, a decent and kindly man – although we won't withdraw our view that he supported an ideology that caused untold misery in the world.

Yes, we accept that he cherished this country's traditions of tolerance and freedom – while, in a troubling paradox typical of the left, detesting the very institutions and political system that made those traditions possible.

And yes, the headline was controversial – but popular newspapers have a long tradition of using provocative headlines to grab readers' attention. In isolation that headline may indeed seem over the top, but read in conjunction with the article we believed it was justifiable.

Despite this we acceded to Mr Miliband's demand – and by golly, he did demand – that we publish his 1,000-word article defending his father.

So it was that, in a virtually unprecedented move, we published his words at the top of our op ed pages. They were accompanied by an abridged version of the original Levy article and a leader explaining why the Mail wasn't apologising for the points it made.

The hysteria that followed is symptomatic of the post-Leveson age in which any newspaper which dares to take on the left in the interests of its readers risks being howled down by the Twitter mob who the BBC absurdly thinks represent the views of real Britain.

As the week progressed and the hysteria increased, it became clear that this was no longer a story about an article on Mr Miliband's Marxist father but a full-scale war by the BBC and the left against the paper that is their most vocal critic.

Orchestrating this bile was an ever more rabid Alastair Campbell. Again, fair-minded readers will wonder why a man who helped drive Dr David Kelly to his death, was behind the dodgy Iraq war dossier and has done more to poison the well of public discourse than anyone in Britain is given so much air-time by the BBC.

But the BBC's blood lust was certainly up. Impartiality flew out of the window. Ancient feuds were settled. Not to put too fine a point on things, we were right royally turned over.

Fair enough, if you dish it out, you take it. But my worry is that there was a more disturbing agenda to last week's events.

Mr Miliband, of course, exults in being the man who destroyed Murdoch in this country. Is it fanciful to believe that his real purpose in triggering last week's row – so assiduously supported by the liberal media which sneers at the popular press – was an attempt to neutralise Associated, the Mail's publishers and one of Britain's most robustly independent and successful newspaper groups.

Let it be said loud and clear that the Mail, unlike News International, did NOT hack people's phones or pay the police for stories. I have sworn that on oath.

No, our crime is more heinous than that.

It is that the Mail constantly dares to stand up to the liberal-left consensus that dominates so many areas of British life and instead represents the views of the ordinary people who are our readers and who don't have a voice in today's political landscape and are too often ignored by today's ruling elite.

The metropolitan classes, of course, despise our readers with their dreams (mostly unfulfilled) of a decent education and health service they can trust, their belief in the family, patriotism, self-reliance, and their over-riding suspicion of the state and the People Who Know Best.

These people mock our readers' scepticism over the European Union and a human rights court that seems to care more about the criminal than the victim. They scoff at our readers who, while tolerant, fret that the country's schools and hospitals can't cope with mass immigration.

In other words, these people sneer at the decent working Britons – I'd argue they are the backbone of this country – they constantly profess to be concerned about.

The truth is that there is an unpleasant intellectual snobbery about the Mail in leftish circles, for whom the word 'suburban' is an obscenity. They simply cannot comprehend how a paper that opposes the mindset they hold dear can be so successful and so loved by its millions of readers.

Well, I'm proud that the Mail stands up for those readers.

I am proud that our Dignity For The Elderly Campaign has for years stood up for Britain's most neglected community. Proud that we have fought for justice for Stephen Lawrence, Gary McKinnon and the relatives of the victims of the Omagh bombing, for those who have seen loved ones suffer because of MRSA and the Liverpool Care Pathway. I am proud that we have led great popular campaigns for the NSPCC and Alzheimer's Society on the dangers of paedophilia and the agonies of dementia. And I'm proud of our war against round-the-clock drinking, casinos, plastic bags, internet pornography and secret courts.

No other newspaper campaigns as vigorously as the Mail and I am proud of the ability of the paper's 400 journalists (the BBC has 8,000) to continually set the national agenda on a whole host of issues.

I am proud that for years, while most of Fleet Street were in thrall to it, the Mail was the only paper to stand up to the malign propaganda machine of Tony Blair and his appalling henchman, Campbell (and, my goodness, it's been payback time over the past week!).

Could all these factors also be behind the left's tsunami of opprobrium against the Mail last week? I don't know but I do know that for a party mired in the corruption exposed by Damian McBride's book (in which Ed Miliband was a central player) to call for a review of the Mail's practices and culture is beyond satire.

Certainly, the Mail will not be silenced by a Labour party that has covered up unnecessary, and often horrific, deaths in NHS hospitals, and suggests instead that it should start looking urgently at its own culture and practices.

Some have argued that last week's brouhaha shows the need for statutory press regulation. I would argue the opposite. The febrile heat, hatred, irrationality and prejudice provoked by last week's row reveals why politicians must not be allowed anywhere near press regulation.

And while the Mail does not agree with the Guardian over the stolen secret security files it published, I suggest that we can agree that the fury and recrimination the story is provoking reveals again why those who rule us – and who should be held to account by newspapers – cannot be allowed to sit in judgment on the press.

That is why the left should be very careful about what it wishes for – especially in the light of this week's rejection by the politicians of the newspaper industry's charter for robust independent self-regulation.

The BBC is controlled, through the licence fee, by the politicians. ITV has to answer to Ofcom, a government quango. Newspapers are the only mass media left in Britain free from the control of the state.

The Mail has recognised the hurt Mr Miliband felt over our attack on his father's beliefs. We were happy to give him considerable space to describe how his father had fought for Britain (though a man who so smoothly diddled his brother risks laying himself open to charges of cynicism if he makes too much of a fanfare over familial loyalties).

For the record, the Mail received a mere two letters of complaint before Mr Miliband's intervention and only a few hundred letters and emails since – many in support. A weekend demonstration against the paper attracted just 110 people.

It seems that in the real world people – most of all our readers – were far more supportive of us than the chatterati would have you believe.

PS – this week the head of MI5 – subsequently backed by the PM, the deputy PM, the home secretary and Labour's elder statesman Jack Straw – effectively accused the Guardian of aiding terrorism by publishing stolen secret security files. The story – which is of huge significance – was given scant coverage by a BBC which only a week ago had devoted days of wall-to-wall pejorative coverage to the Mail. Again, I ask fair readers, what is worse: to criticise the views of a Marxist thinker, whose ideology is anathema to most and who had huge influence on the man who could one day control our security forces … or to put British lives at risk by helping terrorists?

-------

Alastair Campbell's attack on the Mail was terrifying – and brilliant

Campbell's bravura performance took on the Mail's venomous world view, which is that, as an immigrant, you are only ever tolerated

So, to recap the effects of that Daily Mail article on Ralph Miliband: It robbed the Conservative party conference of the headlines it expected – it was ahead of any of their policy announcements all yesterday in most news bulletins, across most channels. It reinforced Ed Miliband's image, for the second week running, as someone of integrity who stands up to bullies. It secured him sympathy and support from most political opponents. It caused a social media reaction which refreshed everyone's memory about the Daily Mail's historical links with Mosley and Hitler. It even managed to revive interest in the Leveson inquiry's recommendations. All in all, it was the journalistic equivalent of a glorious Stan Laurel pratfall.

It also marked the moment when Alastair Campbell singled himself out as the natural successor to Jeremy Paxman. You know, the Paxman of old, when it was his line of questioning which caused a stir, rather than the configuration of his facial fuzz. It was all at once both refreshing to see someone properly "grilled" on Newsnight for the first time in months, and depressing that it had to be by another guest.

It was also, personally, a rather odd moment to find oneself rooting for Alastair Campbell. You got a glimpse of how utterly terrifying he must have been to deal with, when he was Blair's press pointman. How overwhelming and irresistible. A glimpse of how his ability to grind down anyone expressing a contrary view may have contributed to both the success and the hubris of the Labour party at that time. At the same time, as someone hoping that Cameron will be relegated to oblivion at the next election, I had to admit: if I could employ him to help bring that about, I would have to consider it. I may not like him, but – boy – is he good at his job!

Within 10 minutes, he got further than all the other television news political editors and correspondents put together did over 24 hours. He secured an admission from the Mail's deputy editor, Jon Steafel, that, at the very least, using a photograph of Ralph Miliband's grave was an "error". He succeeded in exposing internal rifts within the Daily Mail, by outlining the areas where even Paul Dacre's deputy refused to support him. The coup de grace was the phrase "the Daily Mail is the worst of British values, posing as the best". I suspect it will follow the Mail for many years to come. It was a bravura performance.

He even got close to unpacking the wider point. How is it that one can extrapolate hatred of Britain from criticism of its institutions? It seems that sections of the press (and, I'm sure, the public) are never far from the McCarthyist view, that wanting to change the way the state works makes one an enemy of the state. But there is a further point bubbling under the surface. Implicit in the Daily Mail's venom is the idea that being republican (in the wider, rather than US, sense), being suspicious of organised religion, being a pacifist or a socialist – all these things, which are upsetting to the Mail and its readership – become a cardinal sin if you are also a foreigner.

As a foreigner with strong opinions, I have come across this hundreds of times, in various permutations. As an immigrant one has no right to criticise any aspect of the UK. Regardless of how long one has been here, regardless of the validity of one's opinion, regardless, even, it seems, of serving in the military during a war, the immigrant's stake is limited. He is tolerated, but should watch himself. The invitation can easily be withdrawn. He should be grateful unconditionally. That Daily Mail article is just a longer version of, "If you don't like it here, you can fuck off back to your own country". It is an attitude that is not only still prevalent, but permeates the political rhetoric on Europe, trade, foreign policy and immigration.

It is this snobbery, resistance to new ideas and sense of inflated ego that are truly holding Britain back from being all it can be. It puts me in mind of something the American journalist and essayist Sydney J Harris wrote:

"Patriotism is proud of a country's virtues and eager to correct its deficiencies; it also acknowledges the legitimate patriotism of other countries, with their own specific virtues. The pride of nationalism, however, trumpets its country's virtues and denies its deficiencies, while it is contemptuous toward the virtues of other countries. It wants to be, and proclaims itself to be, 'the greatest', but greatness is not required of a country; only goodness is."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)