'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label authoritarian. Show all posts

Showing posts with label authoritarian. Show all posts

Wednesday, 5 June 2024

Sunday, 28 April 2024

Tuesday, 26 March 2024

Sunday, 10 March 2024

Monday, 14 August 2023

A level Economics: Are Universal Values a form of Imperialism?

They argue that universal values are the new imperialism, imposed on people who want security and stability instead. Here is why they are wrong argues The Economist

Universal and valuable

However, the deepest solution to insecurity lies in how countries cope with change, whether from global warming, artificial intelligence or the growing tensions between China and America. The countries that manage change well will be better at making society feel confident in the future. And that is where universal values come into their own. Tolerance, free expression and individual inquiry help harness change through consensus forged by reasoned debate and reform. There is no better way to bring about progress.

Universal values are much more than a Western piety. They are a mechanism that fortifies societies against insecurity. What the World Values Survey shows is that they are also hard-won.

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 held out the promise that growing prosperity would foster freedom and tolerance, which in turn would create more prosperity. Unfortunately, that hope disappointed. Our analysis this week, based on the definitive global survey of social attitudes, shows just how naive it turned out to be.

Prosperity certainly rose. In the three decades to 2019, global output increased more than fourfold. Roughly 70% of the 2bn people living in extreme poverty escaped it. But individual freedom and tolerance evolved differently. Many people around the world continue to swear fealty to traditional beliefs, sometimes intolerant ones. And although they are much wealthier these days, they often have an us-and-them contempt for others.

The World Values Survey takes place every five years. The latest results, which go up to 2022, canvassed almost 130,000 people in 90 countries. Some places, such as Russia and Georgia, are not becoming more tolerant as they grow, but more tightly bound to traditional religious values instead. At the same time, young people in Islamic and Orthodox countries are barely more individualistic or secular than their elders. By contrast, the young in northern Europe and America are racing ahead. Countries where burning the Koran is tolerated and those where it is a crime look on each other with growing incomprehension.

On the face of it, all this supports the campaign by China’s Communist Party to dismiss universal values as racist neo-imperialism. It argues that white Western elites are imposing their own version of freedom and democracy on people who want security and stability instead.

In fact, the survey suggests something more subtle. Contrary to the Chinese argument, universal values are more valuable than ever. Start with the subtlety. China is right that people want security. The survey shows that a sense of threat drives people to seek refuge in family and racial or national groups, while tradition and organised religion offer solace.

This is one way to see America’s doomed attempts to establish democracy in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as the failure of the Arab spring. Amid lawlessness and upheaval, some people sought safety in their tribe or their sect. Hoping that order would be restored, some welcomed the return of dictators.

The subtlety the Chinese argument misses is the fact that cynical politicians sometimes set out to engineer insecurity because they know that frightened people yearn for strongman rule. That is what Bashar al-Assad did in Syria when he released murderous jihadists from his country’s jails at the start of the Arab spring. He bet that the threat of Sunni violence would cause Syrians from other sects to rally round him.

Something similar happened in Russia. After economic collapse and jarring reforms in the 1990s, Russians thrived in the 2000s. Between 1999 and 2013, gdp per head increased 12-fold in dollar terms. Yet that did not dispel their accumulated dread. President Vladimir Putin consistently played on their ethno-nationalist insecurities, especially when growth later faltered. That has culminated in his disastrous invasion of Ukraine.

Even in established democracies, polarising politicians like Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro, former presidents of America and Brazil, saw that they could exploit left-behind voters’ anxieties to mobilise support. So they set about warning that their political opponents wanted to destroy their supporters’ way of life and threatened the very survival of their countries. That has, in turn, spread alarm and hostility on the other side.

Even allowing for this, the Chinese claim that universal values are an imposition is upside down. From Chile to Japan, the World Values Survey provides examples where growing security really does seem to lead to tolerance and greater individual expression. Nothing suggests that Western countries are unique in that. The real question is how to help people feel more secure.

China’s answer is based on creating order for a loyal, deferential majority that stays out of politics and avoids defying their rulers. However, within that model lurks deep insecurity. It is a majoritarian system in which lines move, sometimes arbitrarily or without warning—especially when power passes unpredictably from one party chief to another.

A better answer comes from prosperity built on the rule of law. Wealthy countries have more resources to spend on dealing with disasters, such as pandemic disease. Likewise, confident in their savings and the social safety-net, the citizens of rich countries know that they are less vulnerable to the chance events that wreck lives elsewhere.

Prosperity certainly rose. In the three decades to 2019, global output increased more than fourfold. Roughly 70% of the 2bn people living in extreme poverty escaped it. But individual freedom and tolerance evolved differently. Many people around the world continue to swear fealty to traditional beliefs, sometimes intolerant ones. And although they are much wealthier these days, they often have an us-and-them contempt for others.

The World Values Survey takes place every five years. The latest results, which go up to 2022, canvassed almost 130,000 people in 90 countries. Some places, such as Russia and Georgia, are not becoming more tolerant as they grow, but more tightly bound to traditional religious values instead. At the same time, young people in Islamic and Orthodox countries are barely more individualistic or secular than their elders. By contrast, the young in northern Europe and America are racing ahead. Countries where burning the Koran is tolerated and those where it is a crime look on each other with growing incomprehension.

On the face of it, all this supports the campaign by China’s Communist Party to dismiss universal values as racist neo-imperialism. It argues that white Western elites are imposing their own version of freedom and democracy on people who want security and stability instead.

In fact, the survey suggests something more subtle. Contrary to the Chinese argument, universal values are more valuable than ever. Start with the subtlety. China is right that people want security. The survey shows that a sense of threat drives people to seek refuge in family and racial or national groups, while tradition and organised religion offer solace.

This is one way to see America’s doomed attempts to establish democracy in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as the failure of the Arab spring. Amid lawlessness and upheaval, some people sought safety in their tribe or their sect. Hoping that order would be restored, some welcomed the return of dictators.

The subtlety the Chinese argument misses is the fact that cynical politicians sometimes set out to engineer insecurity because they know that frightened people yearn for strongman rule. That is what Bashar al-Assad did in Syria when he released murderous jihadists from his country’s jails at the start of the Arab spring. He bet that the threat of Sunni violence would cause Syrians from other sects to rally round him.

Something similar happened in Russia. After economic collapse and jarring reforms in the 1990s, Russians thrived in the 2000s. Between 1999 and 2013, gdp per head increased 12-fold in dollar terms. Yet that did not dispel their accumulated dread. President Vladimir Putin consistently played on their ethno-nationalist insecurities, especially when growth later faltered. That has culminated in his disastrous invasion of Ukraine.

Even in established democracies, polarising politicians like Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro, former presidents of America and Brazil, saw that they could exploit left-behind voters’ anxieties to mobilise support. So they set about warning that their political opponents wanted to destroy their supporters’ way of life and threatened the very survival of their countries. That has, in turn, spread alarm and hostility on the other side.

Even allowing for this, the Chinese claim that universal values are an imposition is upside down. From Chile to Japan, the World Values Survey provides examples where growing security really does seem to lead to tolerance and greater individual expression. Nothing suggests that Western countries are unique in that. The real question is how to help people feel more secure.

China’s answer is based on creating order for a loyal, deferential majority that stays out of politics and avoids defying their rulers. However, within that model lurks deep insecurity. It is a majoritarian system in which lines move, sometimes arbitrarily or without warning—especially when power passes unpredictably from one party chief to another.

A better answer comes from prosperity built on the rule of law. Wealthy countries have more resources to spend on dealing with disasters, such as pandemic disease. Likewise, confident in their savings and the social safety-net, the citizens of rich countries know that they are less vulnerable to the chance events that wreck lives elsewhere.

Universal and valuable

However, the deepest solution to insecurity lies in how countries cope with change, whether from global warming, artificial intelligence or the growing tensions between China and America. The countries that manage change well will be better at making society feel confident in the future. And that is where universal values come into their own. Tolerance, free expression and individual inquiry help harness change through consensus forged by reasoned debate and reform. There is no better way to bring about progress.

Universal values are much more than a Western piety. They are a mechanism that fortifies societies against insecurity. What the World Values Survey shows is that they are also hard-won.

Saturday, 25 December 2021

What is Modi-Shah BJP’s ideology? You’re wrong if you say Right wing, because it’s Hindu Left

Modi-Shah BJP government is Right only on religion and nationalism. The rest is as Left as the Congress or any other.writes SHEKHAR GUPTA in The Print

Prashant Kishor, who prefers to be described as a political aide rather than a strategist, which is generally the preferred usage for him, featured in our serious conversational show ‘Off The Cuff’ this week. Neelam Pandey, a senior member of our political reporting team at ThePrint, co-hosted it with me.

At some point, we asked him the question that’s always intrigued us. Does he have an ideology? Doesn’t that follow from the fact that he’s worked with Narendra Modi, Mamata Banerjee, Congress-SP (Uttar Pradesh, 2017), M.K. Stalin, Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy, Amarinder Singh and more?

To our surprise, he said no, I am not ideology-agnostic, you can call me Left-of-Centre. And then went on to elaborate what he meant, by using Mahatma Gandhi’s example. And so on. I noticed later, incidentally, that Kishor’s Twitter bio begins with the words “Revere Gandhi…”

His claim to a Centre-Left ideology set us thinking. What if we asked any of the other key political leaders the same question today? What is your ideology? Rahul and Priyanka Gandhi, Mamata Banerjee, Andhra’s Jagan, Tamil Nadu’s Stalin, Telangana’s KCR and so on. If any of them chooses to answer that question — the answer, honest or not, will be about the same. Everyone in Indian politics now wades in the waters of varying depth somewhere on the Left side of the pool. Nobody will say I stand on the Right.

Which brings us to the trick question. What would Narendra Modi’s answer be? We are, of course, making a brave and far-out presumption that he lets us or anyone ask him such a direct question: What’s your ideology, Prime Minister sir? Now, whether you are fan or a critic, chances are, your immediate response will be, of course the Right wing.

Over the past seven years since the Modi-Shah BJP has been in power, “Right wing” has become the widely accepted usage for the party, and the ideological forces behind it. We need to examine if this passes the test of facts. And fasten seat belts. Because, I will then make the case to you that what Modi and his BJP represent today is not a domineering national force of the Hindu Right. It is, on the other hand, the Hindu Left.

The Left-Right descriptors over time have become mixed up and confusing. In governance terms, the Right means first of all, social conservatism, strong religiosity, hard nationalism, low threshold for criticism, an authoritarian outlook. On all these parameters, the Modi government and today’s BJP pass the test of being Right wing. The reason I qualify it here is that we do not get caught in simplistic binaries. On all of these, this BJP and Modi are no different from, say, the Republicans in the US or the British Conservatives. Then, we enter contentious zones.

How do we, then come to our argument that the Modi-Shah-Yogi BJP is not a force of the pure Right or even the Hindu Right, but of the Hindu Left?

Check out the many steps the Modi government has taken on the economy in the past seven-plus years. For historical reference, look back at the previous BJP government under Atal Bihari Vajpayee. It made its commitment to getting the government out of business explicit, and set up a disinvestment ministry. When the party returned to power in 2014, you would have expected it to bring that ministry back. No such thing happened, although now there is a department, DIPAM, in the finance ministry with a full secretary.

It is only now that there is heady talk of disinvestment, but not so much has happened yet, with the sterling exception of Air India. Much other privatisation is still merely talk, or sleight of hand. As in, getting one public sector giant to acquire a smaller one, and the government, as the majority shareholder, cashing out to balance its deficit. But it is, as we had said in an earlier National Interest, like genius Milo Minderbender of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 trading with himself and making a profit. Of course, using the state’s products and cash.

Actually, this gets worse than a sleight of hand often enough. Think of the LIC, or even ONGC, being made to buy another PSU the government wants to ‘disinvest’ from. A bunch of money is paid out to the government. Our complaint isn’t that it disappears into that bottomless pit called the Consolidated Fund of India. If you believed in a market economy, you would have no complaint if the LIC or ONGC paid out dividends from its profits to its only, or overwhelming, shareholder, the government. But when the government makes them buy assets from it, these companies are not necessarily acting in the best interests of the policy holder or the minority shareholder. We are not saying that it always works out to their detriment, but the fact is these are not decisions these companies’ boards are taking with these non-sarkari shareholders’ interests at the top of their minds. This is a characteristic of the Left, not Right.

The Left is also known for handout economics, large, ambitious, welfare schemes involving redistribution of large chunks of the revenues. Which is precisely what the Modi government has been doing, from the MGNREGA it inherited to Gram Awas, toilet-building, Ujjwala, direct cash transfers to farmers and the poor, free grain and so on. Have you noticed, in fact, how muted as the opposition criticism of this governments’ Budgets has been?

There is some usual sniggering about being “pro-rich” etc. But everybody also notices that taxes on individuals now are the highest — almost 44 per cent — since reform began. Add to that an average of 18 per cent or so GST on goods and services that people, especially the rich, consume. The Left would applaud this. Of course, they’d want this to be even higher. Hopefully not the 97 per cent it was at Indira Gandhi’s socialist peak, when the foundation of the parallel black economy was laid.

An expanding, large, maai-baap (mom & dad) sarkar is something the Leftists love. See the expansion of our government in the Modi era. More and more Bhawans have come up in Delhi to accommodate a burgeoning government. Now the new Central Vista will create space for more. A comparison again with Vajpayee government. He had no hesitation selling the loss-making Lodhi Hotel in the heart of Delhi. An even bigger PSU dud was Hotel Janpath. Which, instead of being sold, has now become another set of offices and government accommodation. Samrat Hotel, next to Ashoka, ceased to be a hotel a long time ago. It has become a sarkari bhawan too. In fact, almost everyone here will be surprised when I tell you that even the new Lok Pal (do you remember we had appointed one? Okay, what’s his name?) has been given half a floor here.

Our taxes are higher than in a generation, our government is bigger than two generations and still growing, we ‘privatise’ our companies often by selling one PSU to another, now our government also decides for all of the country which Covid vaccine to have when, to be allowed boosters or not, and what can be sold in India. In a genuinely free market, there will be shops and buyers for Covaxin, Covishield, Sputnik, Pfizer and Moderna.

As with cars, consumers can choose a Maruti or a Mercedes. But not vaccines. Why? Because ours is a maai-baap sarkar. It is in no way a government of the economic Right. The Right is limited to religion and nationalism. The rest is as Left as the Congress or any other. The reason we call Modi-BJP ideology as the Hindu Left.

Prashant Kishor, who prefers to be described as a political aide rather than a strategist, which is generally the preferred usage for him, featured in our serious conversational show ‘Off The Cuff’ this week. Neelam Pandey, a senior member of our political reporting team at ThePrint, co-hosted it with me.

At some point, we asked him the question that’s always intrigued us. Does he have an ideology? Doesn’t that follow from the fact that he’s worked with Narendra Modi, Mamata Banerjee, Congress-SP (Uttar Pradesh, 2017), M.K. Stalin, Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy, Amarinder Singh and more?

To our surprise, he said no, I am not ideology-agnostic, you can call me Left-of-Centre. And then went on to elaborate what he meant, by using Mahatma Gandhi’s example. And so on. I noticed later, incidentally, that Kishor’s Twitter bio begins with the words “Revere Gandhi…”

His claim to a Centre-Left ideology set us thinking. What if we asked any of the other key political leaders the same question today? What is your ideology? Rahul and Priyanka Gandhi, Mamata Banerjee, Andhra’s Jagan, Tamil Nadu’s Stalin, Telangana’s KCR and so on. If any of them chooses to answer that question — the answer, honest or not, will be about the same. Everyone in Indian politics now wades in the waters of varying depth somewhere on the Left side of the pool. Nobody will say I stand on the Right.

Which brings us to the trick question. What would Narendra Modi’s answer be? We are, of course, making a brave and far-out presumption that he lets us or anyone ask him such a direct question: What’s your ideology, Prime Minister sir? Now, whether you are fan or a critic, chances are, your immediate response will be, of course the Right wing.

Over the past seven years since the Modi-Shah BJP has been in power, “Right wing” has become the widely accepted usage for the party, and the ideological forces behind it. We need to examine if this passes the test of facts. And fasten seat belts. Because, I will then make the case to you that what Modi and his BJP represent today is not a domineering national force of the Hindu Right. It is, on the other hand, the Hindu Left.

The Left-Right descriptors over time have become mixed up and confusing. In governance terms, the Right means first of all, social conservatism, strong religiosity, hard nationalism, low threshold for criticism, an authoritarian outlook. On all these parameters, the Modi government and today’s BJP pass the test of being Right wing. The reason I qualify it here is that we do not get caught in simplistic binaries. On all of these, this BJP and Modi are no different from, say, the Republicans in the US or the British Conservatives. Then, we enter contentious zones.

How do we, then come to our argument that the Modi-Shah-Yogi BJP is not a force of the pure Right or even the Hindu Right, but of the Hindu Left?

Check out the many steps the Modi government has taken on the economy in the past seven-plus years. For historical reference, look back at the previous BJP government under Atal Bihari Vajpayee. It made its commitment to getting the government out of business explicit, and set up a disinvestment ministry. When the party returned to power in 2014, you would have expected it to bring that ministry back. No such thing happened, although now there is a department, DIPAM, in the finance ministry with a full secretary.

It is only now that there is heady talk of disinvestment, but not so much has happened yet, with the sterling exception of Air India. Much other privatisation is still merely talk, or sleight of hand. As in, getting one public sector giant to acquire a smaller one, and the government, as the majority shareholder, cashing out to balance its deficit. But it is, as we had said in an earlier National Interest, like genius Milo Minderbender of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 trading with himself and making a profit. Of course, using the state’s products and cash.

Actually, this gets worse than a sleight of hand often enough. Think of the LIC, or even ONGC, being made to buy another PSU the government wants to ‘disinvest’ from. A bunch of money is paid out to the government. Our complaint isn’t that it disappears into that bottomless pit called the Consolidated Fund of India. If you believed in a market economy, you would have no complaint if the LIC or ONGC paid out dividends from its profits to its only, or overwhelming, shareholder, the government. But when the government makes them buy assets from it, these companies are not necessarily acting in the best interests of the policy holder or the minority shareholder. We are not saying that it always works out to their detriment, but the fact is these are not decisions these companies’ boards are taking with these non-sarkari shareholders’ interests at the top of their minds. This is a characteristic of the Left, not Right.

The Left is also known for handout economics, large, ambitious, welfare schemes involving redistribution of large chunks of the revenues. Which is precisely what the Modi government has been doing, from the MGNREGA it inherited to Gram Awas, toilet-building, Ujjwala, direct cash transfers to farmers and the poor, free grain and so on. Have you noticed, in fact, how muted as the opposition criticism of this governments’ Budgets has been?

There is some usual sniggering about being “pro-rich” etc. But everybody also notices that taxes on individuals now are the highest — almost 44 per cent — since reform began. Add to that an average of 18 per cent or so GST on goods and services that people, especially the rich, consume. The Left would applaud this. Of course, they’d want this to be even higher. Hopefully not the 97 per cent it was at Indira Gandhi’s socialist peak, when the foundation of the parallel black economy was laid.

An expanding, large, maai-baap (mom & dad) sarkar is something the Leftists love. See the expansion of our government in the Modi era. More and more Bhawans have come up in Delhi to accommodate a burgeoning government. Now the new Central Vista will create space for more. A comparison again with Vajpayee government. He had no hesitation selling the loss-making Lodhi Hotel in the heart of Delhi. An even bigger PSU dud was Hotel Janpath. Which, instead of being sold, has now become another set of offices and government accommodation. Samrat Hotel, next to Ashoka, ceased to be a hotel a long time ago. It has become a sarkari bhawan too. In fact, almost everyone here will be surprised when I tell you that even the new Lok Pal (do you remember we had appointed one? Okay, what’s his name?) has been given half a floor here.

Our taxes are higher than in a generation, our government is bigger than two generations and still growing, we ‘privatise’ our companies often by selling one PSU to another, now our government also decides for all of the country which Covid vaccine to have when, to be allowed boosters or not, and what can be sold in India. In a genuinely free market, there will be shops and buyers for Covaxin, Covishield, Sputnik, Pfizer and Moderna.

As with cars, consumers can choose a Maruti or a Mercedes. But not vaccines. Why? Because ours is a maai-baap sarkar. It is in no way a government of the economic Right. The Right is limited to religion and nationalism. The rest is as Left as the Congress or any other. The reason we call Modi-BJP ideology as the Hindu Left.

Saturday, 7 March 2020

150 years of data proves it: Strongmen are bad for the economy

By Annalisa Merelli in QZ.com

As governments around the world gravitate toward rightwing populist and authoritarian leaders, many have pointed to the 2008 global recession and the economic hardship that followed as the reason.

Take America, for instance: According to many analysts, the rise of US president Donald Trump has to be seen in relation to the great recession, and was aided by a frustrated working and middle class that saw in his election the promise of new economic wellbeing.

This repeats a historical pattern: When facing dire straits, populations tend to delegate responsibility and look for a leader who can (or at least promise to) get them back to better times.

It’s a bad idea, however, and not just for democracy: It’s terrible for the economy, too.

A study by researchers of the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology and Victoria University in Melbourne published in Leadership Quarterly looked at economic data in relation to the performances of authoritarian leaders versus democratic governments.

The authors analyzed the governments of 133 countries between 1858 to 2010, and found that autocrats were either damaging or inconsequential for the economy of their countries. Besides showing the poor economic outcomes of oppressive regimes, the study calls into question the idea of “benevolent dictators”—for instance Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew or Rwanda’s Paul Kagame—who are commonly believed to be good for the economy.

“Autocrats with positive effects are found at best as frequently as predicted by chance, while autocrats with negative effects are found in abundance,” wrote Stephanie Rizio and Ahmed Skali, the authors of the paper. Strongmen mostly leave a county’s economy worse than they found it, or simply “ride the wave” of an economic growth that would have happened regardless of their rule.

The researchers used data from the Archigos dataset of leaders, which lists both the leaders of countries and the person with the most power in a country at any given time. The official head of state might sometimes be no more than a figurehead, while someone else holds the actual power. For instance, the paper notes that Septimus Rameau was the de-facto ruler of Haiti between 1874 and 1876, while his uncle Michel Domingue was the official leader; or Ziaur Rahman, who was actually in charge of Bangladesh between 1975 and 1977, while Abu Sadat Mohammad Sayem was the country’s official leader.

---Also watch

As governments around the world gravitate toward rightwing populist and authoritarian leaders, many have pointed to the 2008 global recession and the economic hardship that followed as the reason.

Take America, for instance: According to many analysts, the rise of US president Donald Trump has to be seen in relation to the great recession, and was aided by a frustrated working and middle class that saw in his election the promise of new economic wellbeing.

This repeats a historical pattern: When facing dire straits, populations tend to delegate responsibility and look for a leader who can (or at least promise to) get them back to better times.

It’s a bad idea, however, and not just for democracy: It’s terrible for the economy, too.

A study by researchers of the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology and Victoria University in Melbourne published in Leadership Quarterly looked at economic data in relation to the performances of authoritarian leaders versus democratic governments.

The authors analyzed the governments of 133 countries between 1858 to 2010, and found that autocrats were either damaging or inconsequential for the economy of their countries. Besides showing the poor economic outcomes of oppressive regimes, the study calls into question the idea of “benevolent dictators”—for instance Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew or Rwanda’s Paul Kagame—who are commonly believed to be good for the economy.

“Autocrats with positive effects are found at best as frequently as predicted by chance, while autocrats with negative effects are found in abundance,” wrote Stephanie Rizio and Ahmed Skali, the authors of the paper. Strongmen mostly leave a county’s economy worse than they found it, or simply “ride the wave” of an economic growth that would have happened regardless of their rule.

The researchers used data from the Archigos dataset of leaders, which lists both the leaders of countries and the person with the most power in a country at any given time. The official head of state might sometimes be no more than a figurehead, while someone else holds the actual power. For instance, the paper notes that Septimus Rameau was the de-facto ruler of Haiti between 1874 and 1876, while his uncle Michel Domingue was the official leader; or Ziaur Rahman, who was actually in charge of Bangladesh between 1975 and 1977, while Abu Sadat Mohammad Sayem was the country’s official leader.

---Also watch

----

The data was then cross-referenced with the Polity IV dataset, which establishes the kind of political government in place for 185 countries every year, defining whether the country is a democracy or an autocracy. For each year, countries are scored from 1 to 10. Scores below 6 indicate an autocratic regime, while democracies stand above six.

To analyze the economic outcome of a strongman’s rule, the researches looked at per capita GDP. The researchers then compared economic growth in countries with autocratic regimes to economic growth in democracies, looking at whether the impact of the autocrats (and the democratic leaders) was relevant—or if the results were ascribable simply to chance.

In the large majority of cases, countries led by autocrats—whether benevolent or otherwise—were found to have worse economic outcomes in terms of growth than democracies. And not just in the short term: The researchers also looked at delayed growth, testing the hypothesis that reforms put in place by a dictator might take time to bear fruit. They found no demonstrable growth to connect with autocratic rule.

Growth isn’t the only economic metric on which autocrats failed to deliver. They also fell short on employment, health and education spending, and government debt.

But—in what is possibly good news for Trump, who is facing the threat of another recession—while it seems people are inclined to vote a strongman into power to fix their economic woes, they aren’t as quick to get rid of him if the economy doesn’t improve. The paper found that while authoritarians do pay for their bad economic performances, it takes much longer for them to lose popular support and be deposed from power than they do in a democracy under comparable economic circumstances.

Skali told Quartz the research didn’t look into the relation between economic hardship and the rise of autocracies, and why distressed populations gravitate towards strongmen. But he did share a speculation: In times of hardship, primates tend to accept, and follow, the authority of an alpha male.

The data was then cross-referenced with the Polity IV dataset, which establishes the kind of political government in place for 185 countries every year, defining whether the country is a democracy or an autocracy. For each year, countries are scored from 1 to 10. Scores below 6 indicate an autocratic regime, while democracies stand above six.

To analyze the economic outcome of a strongman’s rule, the researches looked at per capita GDP. The researchers then compared economic growth in countries with autocratic regimes to economic growth in democracies, looking at whether the impact of the autocrats (and the democratic leaders) was relevant—or if the results were ascribable simply to chance.

In the large majority of cases, countries led by autocrats—whether benevolent or otherwise—were found to have worse economic outcomes in terms of growth than democracies. And not just in the short term: The researchers also looked at delayed growth, testing the hypothesis that reforms put in place by a dictator might take time to bear fruit. They found no demonstrable growth to connect with autocratic rule.

Growth isn’t the only economic metric on which autocrats failed to deliver. They also fell short on employment, health and education spending, and government debt.

But—in what is possibly good news for Trump, who is facing the threat of another recession—while it seems people are inclined to vote a strongman into power to fix their economic woes, they aren’t as quick to get rid of him if the economy doesn’t improve. The paper found that while authoritarians do pay for their bad economic performances, it takes much longer for them to lose popular support and be deposed from power than they do in a democracy under comparable economic circumstances.

Skali told Quartz the research didn’t look into the relation between economic hardship and the rise of autocracies, and why distressed populations gravitate towards strongmen. But he did share a speculation: In times of hardship, primates tend to accept, and follow, the authority of an alpha male.

Monday, 4 September 2017

On India's Supreme Courts: And then there were nine

Constitutions are enlarged and strengthened when courts act as brakes against majoritarian authoritarianism

Sanjay Hegde in The Hindu

In early 2014, Fali Nariman said to me in the corridors of the Supreme Court, “A government with an absolute majority will see a conformist judiciary.” Shortly thereafter, India elected a government with an absolute majority in Parliament.

Mr. Nariman prophesied based on past experiences. During the Emergency, the Supreme Court held in ADM Jabalpur that the fundamental right to life could be taken away or suspended. When asked by Justice H.R. Khanna if the right to life had been suspended during the Emergency, the then Attorney General, Niren De, had replied, “Even if life was taken away illegally, courts are helpless.” Four judges then succumbed to government power and failed to protect the citizen; Justice Khanna was the only dissenter.

The shame of that surrender has often been invoked against every judge who has subsequently held office. Justices Y.V. Chandrachud and P.N. Bhagwati, who were part of that Bench, apologised for that judgment after demitting office. But, as Salman Rushdie wrote: “Shame is like everything else; live with it for long enough and it becomes part of the furniture.” Judicial pusillanimity in the face of an authoritarian government was not entirely unexpected.

Pattern of retreat

The last three years have seen a rather conservative Supreme Court, which bears testimony to Mr. Nariman’s aphorism. The court chose to render ineffective challenges to demonetisation by referring the issue to a Constitution Bench. When lawyers beat up former JNU Students’ Union President Kanhaiya Kumar and journalists in the precincts of Patiala House, a mere stone’s throw away from the Supreme Court, the court chose to swallow its wrath. The court’s refusal to investigate the Birla-Sahara diaries, or to allow Harsh Mander’s plea to challenge Amit Shah’s discharge in a criminal case, all fit into this pattern of retreat. Possibly the sole exception was when the court struck down the National Judicial Appointments Commission Act.

At a time when civil liberties seemed to be again imperilled, people wondered whether the court would firmly stand on the side of the citizens who claimed that their fundamental right to privacy was being taken away by the Aadhaar database.

In response to the citizens’ challenge, the Supreme Court was told by the government that there existed no fundamental right to privacy. The government’s stand was based on M.P. Sharma (delivered by eight judges in 1954) and Kharak Singh (delivered by six judges in 1962). Both these decisions had seemingly held that there was no fundamental right to privacy in the Constitution. Later decisions of smaller Benches had, however, held and proceeded on the basis that there did exist such a right.

At least two generations of Indians grew up assuming that a fundamental right to privacy existed. But because of diverse judicial opinions, the matter had to be considered by a Bench of at least nine judges. Assembling nine judges is not an easy task given the abnormal workload and administrative disruption it causes the court. It took nearly two years for a Bench to be constituted, by which time the administration tried to compulsorily impose Aadhaar on every sphere of human activity.

The government took an extreme stand that no fundamental right to privacy existed and that the later judgments were wrongly decided. It was a submission of the sort characterised by Lord Atkin in his 1948 dissent in Liversidge v. Anderson, as an argument that “might have been addressed acceptably to the Court of King’s Bench in the time of Charles I.” The government lost the argument 9-0.

The nine-judge Bench has unanimously held that the right to privacy is a fundamental right and clarified years of somewhat uncertain case law on the subject. It has unequivocally held that the doctrinal premise of M.P. Sharma and Kharak Singh stand invalidated. Nearly half of the 547-page judgment has been written by Justice D.Y. Chandrachud who has recognised that “the right to privacy is an element of human dignity”. Perhaps, even more crucially, Justice Chandrachud (joined by all the others on the Bench), has explicitly overruled the ADM Jabalpur judgment to which his father was a party. The judgment is also remarkable for its stinging criticism of the court’s view in Suresh Koushal, which had upheld the validity of Section 377 of the IPC. The challenge to Section 377 is pending before a different Bench.

What the judges held

Justice J. Chelameswar writes a wonderful enunciation of the rationale behind the Constitution, its Preamble, and the fundamental rights chapter. He points out that provisions purportedly conferring power on the state are, in fact, limitations on the state’s power to infringe on the liberty of citizens. Crucially, after holding that the right to privacy is a fundamental right, he states that the right to privacy includes, among other things, freedom from intrusion into one’s home, the right to choice of food and dress of one’s choice, and the freedom to associate with the people one wants to.

Justice S.A. Bobde holds that privacy is integral to the several fundamental rights recognised by the Constitution. He holds that in case of infringement, the state must satisfy the tests applicable to whichever one or more of the fundamental rights is/are affected by the interference. He also traces the right to privacy to ancient Indian texts including the Grihya Sutras, the Ramayanaand the Arthashastra.

Tracing the right to privacy to the Preamble and the fundamental rights chapter of the Constitution, Justice A.M. Sapre holds that the right to privacy is born with the human being and stays until death. He also holds that the unity and integrity of the nation can only be ensured when the dignity of every citizen is guaranteed through privacy.

Justice S.K. Kaul’s opinion makes a strong case for the horizontal application of fundamental rights. He observes that “digital footprints and extensive data can be analysed computationally to reveal patterns, trends, and associations, especially relating to human behaviour and interactions and hence, is valuable information.” He expresses concern over the use of such data to “exercise control over us like the ‘big brother’ state exercised.”

Justice Rohinton Nariman has rejected the Union’s argument that the right to privacy is not a fundamental right in a developing country where people do not have access to food, shelter and other resources. He holds that the right to privacy is available to the rich and the poor alike: “Fundamental rights, on the other hand, are contained in the Constitution so that there would be rights that the citizens of this country may enjoy despite the governments that they may elect. The recognition of such right in the fundamental rights chapter of the Constitution is only a recognition that such right exists notwithstanding the shifting sands of majority governments.”

In a mature democracy, conformist judiciaries are not always guaranteed to governments with a popular majority. Constitutions are enlarged and strengthened when courts act as brakes against majoritarian authoritarianism. The larger security of the state lies in the protection of every individual’s freedoms. The judges of the Supreme Court, as sentinels on the qui vive, have stood tall and repelled yet another attack on citizens’ liberties. Fali Nariman and Y.V. Chandrachud’s anxieties and reverses of the Emergency era may just have been put to rest.

Sanjay Hegde in The Hindu

In early 2014, Fali Nariman said to me in the corridors of the Supreme Court, “A government with an absolute majority will see a conformist judiciary.” Shortly thereafter, India elected a government with an absolute majority in Parliament.

Mr. Nariman prophesied based on past experiences. During the Emergency, the Supreme Court held in ADM Jabalpur that the fundamental right to life could be taken away or suspended. When asked by Justice H.R. Khanna if the right to life had been suspended during the Emergency, the then Attorney General, Niren De, had replied, “Even if life was taken away illegally, courts are helpless.” Four judges then succumbed to government power and failed to protect the citizen; Justice Khanna was the only dissenter.

The shame of that surrender has often been invoked against every judge who has subsequently held office. Justices Y.V. Chandrachud and P.N. Bhagwati, who were part of that Bench, apologised for that judgment after demitting office. But, as Salman Rushdie wrote: “Shame is like everything else; live with it for long enough and it becomes part of the furniture.” Judicial pusillanimity in the face of an authoritarian government was not entirely unexpected.

Pattern of retreat

The last three years have seen a rather conservative Supreme Court, which bears testimony to Mr. Nariman’s aphorism. The court chose to render ineffective challenges to demonetisation by referring the issue to a Constitution Bench. When lawyers beat up former JNU Students’ Union President Kanhaiya Kumar and journalists in the precincts of Patiala House, a mere stone’s throw away from the Supreme Court, the court chose to swallow its wrath. The court’s refusal to investigate the Birla-Sahara diaries, or to allow Harsh Mander’s plea to challenge Amit Shah’s discharge in a criminal case, all fit into this pattern of retreat. Possibly the sole exception was when the court struck down the National Judicial Appointments Commission Act.

At a time when civil liberties seemed to be again imperilled, people wondered whether the court would firmly stand on the side of the citizens who claimed that their fundamental right to privacy was being taken away by the Aadhaar database.

In response to the citizens’ challenge, the Supreme Court was told by the government that there existed no fundamental right to privacy. The government’s stand was based on M.P. Sharma (delivered by eight judges in 1954) and Kharak Singh (delivered by six judges in 1962). Both these decisions had seemingly held that there was no fundamental right to privacy in the Constitution. Later decisions of smaller Benches had, however, held and proceeded on the basis that there did exist such a right.

At least two generations of Indians grew up assuming that a fundamental right to privacy existed. But because of diverse judicial opinions, the matter had to be considered by a Bench of at least nine judges. Assembling nine judges is not an easy task given the abnormal workload and administrative disruption it causes the court. It took nearly two years for a Bench to be constituted, by which time the administration tried to compulsorily impose Aadhaar on every sphere of human activity.

The government took an extreme stand that no fundamental right to privacy existed and that the later judgments were wrongly decided. It was a submission of the sort characterised by Lord Atkin in his 1948 dissent in Liversidge v. Anderson, as an argument that “might have been addressed acceptably to the Court of King’s Bench in the time of Charles I.” The government lost the argument 9-0.

The nine-judge Bench has unanimously held that the right to privacy is a fundamental right and clarified years of somewhat uncertain case law on the subject. It has unequivocally held that the doctrinal premise of M.P. Sharma and Kharak Singh stand invalidated. Nearly half of the 547-page judgment has been written by Justice D.Y. Chandrachud who has recognised that “the right to privacy is an element of human dignity”. Perhaps, even more crucially, Justice Chandrachud (joined by all the others on the Bench), has explicitly overruled the ADM Jabalpur judgment to which his father was a party. The judgment is also remarkable for its stinging criticism of the court’s view in Suresh Koushal, which had upheld the validity of Section 377 of the IPC. The challenge to Section 377 is pending before a different Bench.

What the judges held

Justice J. Chelameswar writes a wonderful enunciation of the rationale behind the Constitution, its Preamble, and the fundamental rights chapter. He points out that provisions purportedly conferring power on the state are, in fact, limitations on the state’s power to infringe on the liberty of citizens. Crucially, after holding that the right to privacy is a fundamental right, he states that the right to privacy includes, among other things, freedom from intrusion into one’s home, the right to choice of food and dress of one’s choice, and the freedom to associate with the people one wants to.

Justice S.A. Bobde holds that privacy is integral to the several fundamental rights recognised by the Constitution. He holds that in case of infringement, the state must satisfy the tests applicable to whichever one or more of the fundamental rights is/are affected by the interference. He also traces the right to privacy to ancient Indian texts including the Grihya Sutras, the Ramayanaand the Arthashastra.

Tracing the right to privacy to the Preamble and the fundamental rights chapter of the Constitution, Justice A.M. Sapre holds that the right to privacy is born with the human being and stays until death. He also holds that the unity and integrity of the nation can only be ensured when the dignity of every citizen is guaranteed through privacy.

Justice S.K. Kaul’s opinion makes a strong case for the horizontal application of fundamental rights. He observes that “digital footprints and extensive data can be analysed computationally to reveal patterns, trends, and associations, especially relating to human behaviour and interactions and hence, is valuable information.” He expresses concern over the use of such data to “exercise control over us like the ‘big brother’ state exercised.”

Justice Rohinton Nariman has rejected the Union’s argument that the right to privacy is not a fundamental right in a developing country where people do not have access to food, shelter and other resources. He holds that the right to privacy is available to the rich and the poor alike: “Fundamental rights, on the other hand, are contained in the Constitution so that there would be rights that the citizens of this country may enjoy despite the governments that they may elect. The recognition of such right in the fundamental rights chapter of the Constitution is only a recognition that such right exists notwithstanding the shifting sands of majority governments.”

In a mature democracy, conformist judiciaries are not always guaranteed to governments with a popular majority. Constitutions are enlarged and strengthened when courts act as brakes against majoritarian authoritarianism. The larger security of the state lies in the protection of every individual’s freedoms. The judges of the Supreme Court, as sentinels on the qui vive, have stood tall and repelled yet another attack on citizens’ liberties. Fali Nariman and Y.V. Chandrachud’s anxieties and reverses of the Emergency era may just have been put to rest.

Sunday, 17 July 2016

Turkey was already undergoing a slow-motion coup – by Erdoğan, not the army

Andrew Finkel in The Guardian

People hold a banner depicting Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as they gather outside the Turkish parliament in Ankara on 16 July. Photograph: Adem Altan/AFP/Getty Images

What happens in Turkey matters. It is a G20 economy in a sensitive part of the world, sharing borders with Iraq, Iran and Syria. Turkey is an asset to its Nato partners when it is able to exercise a leadership role. It can be a liability when its own problems – like the tension with its Kurdish population – spill over those frontiers. And it can be a millstone around the world’s neck when it decides, as it did on Friday, to self-harm.

The coup attempt that night was, by any account, a cack-handed affair. It was an attempt to grab the reins of a complex society with the almost quaintly antediluvian tactics of seizing the state television station and rolling some tanks on to the streets. It is as if the plotters had never heard of social media, while the Turkish president himself to addressed his supporters via FaceTime, urging them out on the streets. Crowds played chicken with the putschists, betting they would return to their barracks rather than have the streets run red with blood. Even then, at least 180 people – civilians, police and coup makers – died.

Indeed, the question is less why the coup failed than why it was ever carried out. If it had an air of amateur desperation, it is because its perpetrators probably assumed that this was their last chance to stop the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan from getting the military completely under its control. At the beginning of August, the military high council will meet, as it does every year, to consider who gets promoted, retired or pushed aside. In the last few days, the pro-government press has been more than hinting that a spring cleaning of the ranks is long overdue.

Indeed, many would argue that Turkey was already in the throes of a slow motion coup d’état, not by the military but by Erdoğan himself. For the last three years, he has been moving, and methodically, to take over the nodes of power.

The pressures on the media have been well documented, as the country slides in international ratings by organisations such as Freedom House, from partly free to not free at all. Opposition newspapers have been taken over by court-appointed administrators. Dissident television stations have had the plug pulled from satellites; digital platforms are no longer seen in people’s homes. Erdoğan curses the very social media which this weekend helped to save his skin.

Increasingly, the government has put the judiciary under its thumb. It is now a brave judge who rules in a way he knows will give official offence. So while the Turkish parliament congratulated itself on a long night’s defence of democracy, many wonder why its members connived in the decline of the rule of law.

And still Erdoğan craves greater authority. Last May, he discarded one prime minister in favour of another more sympathetic to his plans to change the parliamentary system into a strong executive presidency. When the coup plotters stand trial, they may suffer the additional indignation of seeing their attempts to put Erdoğan in his place backfire, by providing a mandate for such increased powers. The president has already promised a purge of those still connected to the exiled dissident cleric Fethullah Gülen – Erdoğanspeak for anyone who opposes his will.

To the outside world, this spectacle should cause dismay. Turkish ambitions to project power, to assist in the fight against Islamic State, to help forge a settlement in Syria will be much harder to realise if the government is at war with its own military and the army at war with itself. A Turkey that governs through consensus is the more valuable ally. The Turkish economy, too, will be more buoyant if relieved of the weight of political risk.

The lesson of the failed coup is that Turkey needs a leader who can bring different sides of a divided society together – or at the very least, one who is willing to try.

People hold a banner depicting Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as they gather outside the Turkish parliament in Ankara on 16 July. Photograph: Adem Altan/AFP/Getty Images

What happens in Turkey matters. It is a G20 economy in a sensitive part of the world, sharing borders with Iraq, Iran and Syria. Turkey is an asset to its Nato partners when it is able to exercise a leadership role. It can be a liability when its own problems – like the tension with its Kurdish population – spill over those frontiers. And it can be a millstone around the world’s neck when it decides, as it did on Friday, to self-harm.

The coup attempt that night was, by any account, a cack-handed affair. It was an attempt to grab the reins of a complex society with the almost quaintly antediluvian tactics of seizing the state television station and rolling some tanks on to the streets. It is as if the plotters had never heard of social media, while the Turkish president himself to addressed his supporters via FaceTime, urging them out on the streets. Crowds played chicken with the putschists, betting they would return to their barracks rather than have the streets run red with blood. Even then, at least 180 people – civilians, police and coup makers – died.

Indeed, the question is less why the coup failed than why it was ever carried out. If it had an air of amateur desperation, it is because its perpetrators probably assumed that this was their last chance to stop the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan from getting the military completely under its control. At the beginning of August, the military high council will meet, as it does every year, to consider who gets promoted, retired or pushed aside. In the last few days, the pro-government press has been more than hinting that a spring cleaning of the ranks is long overdue.

Indeed, many would argue that Turkey was already in the throes of a slow motion coup d’état, not by the military but by Erdoğan himself. For the last three years, he has been moving, and methodically, to take over the nodes of power.

The pressures on the media have been well documented, as the country slides in international ratings by organisations such as Freedom House, from partly free to not free at all. Opposition newspapers have been taken over by court-appointed administrators. Dissident television stations have had the plug pulled from satellites; digital platforms are no longer seen in people’s homes. Erdoğan curses the very social media which this weekend helped to save his skin.

Increasingly, the government has put the judiciary under its thumb. It is now a brave judge who rules in a way he knows will give official offence. So while the Turkish parliament congratulated itself on a long night’s defence of democracy, many wonder why its members connived in the decline of the rule of law.

And still Erdoğan craves greater authority. Last May, he discarded one prime minister in favour of another more sympathetic to his plans to change the parliamentary system into a strong executive presidency. When the coup plotters stand trial, they may suffer the additional indignation of seeing their attempts to put Erdoğan in his place backfire, by providing a mandate for such increased powers. The president has already promised a purge of those still connected to the exiled dissident cleric Fethullah Gülen – Erdoğanspeak for anyone who opposes his will.

To the outside world, this spectacle should cause dismay. Turkish ambitions to project power, to assist in the fight against Islamic State, to help forge a settlement in Syria will be much harder to realise if the government is at war with its own military and the army at war with itself. A Turkey that governs through consensus is the more valuable ally. The Turkish economy, too, will be more buoyant if relieved of the weight of political risk.

The lesson of the failed coup is that Turkey needs a leader who can bring different sides of a divided society together – or at the very least, one who is willing to try.

Friday, 16 May 2014

The new face of India

With the rise of Hindu nationalist Narendra Modi culminating in this week's election, Pankaj Mishra asks if the world's largest democracy is entering its most sinister period since independence

Supporters of Narendra Modi wear masks during a campaign rally in Kolkata. Photograph: Dibyangshu Sarkar/AFP/Getty Images

In A Suitable Boy, Vikram Seth writes with affection of a placid India's first general election in 1951, and the egalitarian spirit it momentarily bestowed on an electorate deeply riven by class and caste: "the great washed and unwashed public, sceptical and gullible", but all "endowed with universal adult suffrage". India's 16th general election this month, held against a background of economic jolts and titanic corruption scandals, and tainted by the nastiest campaign yet, announces a new turbulent phase for the country – arguably, the most sinister since its independence from British rule in 1947. Back then, it would have been inconceivable that a figure such as Narendra Modi, the Hindu nationalist chief minister of Gujarat accused, along with his closest aides, of complicity in crimes ranging from an anti-Muslim pogrom in his state in 2002 to extrajudicial killings, and barred from entering the US, may occupy India's highest political office.

Modi is a lifelong member of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a paramilitary Hindu nationalist organisation inspired by the fascist movements of Europe, whose founder's belief that Nazi Germany had manifested "race pride at its highest" by purging the Jews is by no means unexceptional among the votaries of Hindutva, or "Hinduness". In 1948, a former member of the RSS murdered Gandhi for being too soft on Muslims. The outfit, traditionally dominated by upper-caste Hindus, has led many vicious assaults on minorities. A notorious executioner of dozens of Muslims in Gujarat in 2002 crowedthat he had slashed open with his sword the womb of a heavily pregnant woman and extracted her foetus. Modi himself described the relief camps housing tens of thousands of displaced Muslims as "child-breeding centres".

Such rhetoric has helped Modi sweep one election after another in Gujarat. A senior American diplomat described him, in cables disclosed by WikiLeaks, as an "insular, distrustful person" who "reigns by fear and intimidation"; his neo-Hindu devotees on Facebook and Twitter continue to render the air mephitic with hate and malice, populating the paranoid world of both have-nots and haves with fresh enemies – "terrorists", "jihadis", "Pakistani agents", "pseudo-secularists", "sickulars", "socialists" and "commies". Modi's own electoral strategy as prime ministerial candidate, however, has been more polished, despite his appeals, both dog-whistled and overt, to Hindu solidarity against menacing aliens and outsiders, such as the Italian-born leader of the Congress party, Sonia Gandhi, Bangladeshi "infiltrators" and those who eat the holy cow.

Modi exhorts his largely young supporters – more than two-thirds of India's population is under the age of 35 – to join a revolution that will destroy the corrupt old political order and uproot its moral and ideological foundations while buttressing the essential framework, the market economy, of a glorious New India. In an apparently ungovernable country, where many revere the author of Mein Kampf for his tremendous will to power and organisation, he has shrewdly deployed the idioms of management, national security and civilisational glory.

Boasting of his 56-inch chest, Modi has replaced Mahatma Gandhi, the icon of non-violence, with Vivekananda, the 19th-century Hindu revivalist who was obsessed with making Indians a "manly" nation. Vivekananda's garlanded statue or portrait is as ubiquitous in Modi's public appearances as his dandyish pastel waistcoats. But Modi is never less convincing than when he presents himself as a humble tea-vendor, the son-of-the-soil challenger to the Congress's haughty dynasts. His record as chief minister is predominantly distinguished by the transfer – through privatisation or outright gifts – of national resources to the country's biggest corporations. His closest allies – India's biggest businessmen – have accordingly enlisted their mainstream media outlets into the cult of Modi as decisive administrator; dissenting journalists have been removed or silenced.

Mukesh Ambani's 27-storey house in Mumbai. Photograph: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

Mukesh Ambani's 27-storey house in Mumbai. Photograph: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

Not long after India's first full-scale pogrom in 2002, leading corporate bosses, ranging from the suave Ratan Tata to Mukesh Ambani, the owner of a 27-storey residence, began to pave Modi's ascent to respectability and power. The stars of Bollywood fell (literally) at the feet of Modi. In recent months, liberal-minded columnists and journalists have joined their logrolling rightwing compatriots in certifying Modi as a "moderate" developmentalist. The Columbia University economist Jagdish Bhagwati, who insists that he intellectually fathered India's economic reforms in 1991, and Gurcharan Das, author of India Unbound, have volunteered passionate exonerations of the man they consider India's saviour.

Bhagwati, once a fervent supporter of outgoing prime minister Manmohan Singh, has even publicly applied for an advisory position with Modi's government. It may be because the nearly double-digit economic growth of recent years that Ivy League economists like him – India's own version of Chile's Chicago Boys and Russia's Harvard Boys – instigated and championed turns out to have been based primarily on extraction of natural resources, cheap labour and foreign capital inflows rather than high productivity and innovation, or indeed the brick-and-mortar ventures that fuelled China's rise as a manufacturing powerhouse. "The bulk of India's aggregate growth," the World Bank's chief economist Kaushik Basu warns, "is occurring through a disproportionate rise in the incomes at the upper end of the income ladder." Thus, it has left largely undisturbed the country's shameful ratios – 43% of all Indian children below the age of five are undernourished, and 48% stunted; nearly half of Indian women of childbearing age are anaemic, and more than half of all Indians still defecate in the open.

Absurdly uneven and jobless economic growth has led to what Amartya Sen and Jean Dreze call "islands of California in a sea of sub-Saharan Africa". The failure to generate stable employment – 1m new jobs are required every month – for an increasingly urban and atomised population, or to allay the severe inequalities of opportunity as well as income, created, well before the recent economic setbacks, a large simmering reservoir of rage and frustration. Many Indians, neglected by the state, which spends less proportionately on health and education than Malawi, and spurned by private industry, which prefers cheap contract labour, invest their hopes in notions of free enterprise and individual initiative. However, old and new hierarchies of class, caste and education restrict most of them to the ranks of the unwashed. As the Wall Street Journal admitted,India is not "overflowing with Horatio Alger stories". Balram Halwai, the entrepreneur from rural India in Aravind Adiga's Man Booker-winning novel The White Tiger, who finds in murder and theft the quickest route to business success and self-confidence in the metropolis, and Mumbai's social-Darwinist slum-dwellers in Katherine Boo's Behind the Beautiful Forevers point to an intensified dialectic in India today: cruel exclusion and even more brutal self-empowerment.

❦

Such extensive moral squalor may bewilder those who expected India to conform, however gradually and imperfectly, to a western ideal of liberal democracy and capitalism. But those scandalised by the lure of an indigenised fascism in the country billed as the "world's largest democracy" should know: this was not the work of a day, or of a few "extremists". It has been in the making for years. "Democracy in India," BR Ambedkar, the main framer of India's constitution, warned in the 1950s, "is only a top dressing on an Indian soil, which is essentially undemocratic." Ambedkar saw democracy in India as a promise of justice and dignity to the country's despised and impoverished millions, which could only be realised through intense political struggle. For more than two decades that possibility has faced a pincer movement: a form of global capitalism that can only enrich a small minority and a xenophobic nationalism that handily identifies fresh scapegoats for large-scale socio-economic failure and frustration.

In many ways, Modi and his rabble – tycoons, neo-Hindu techies, and outright fanatics – are perfect mascots for the changes that have transformed India since the early 1990s: the liberalisation of the country's economy, and the destruction by Modi's compatriots of the 16th-century Babri mosque in Ayodhya. Long before the killings in Gujarat, Indian security forces enjoyed what amounted to a licence to kill, torture and rape in the border regions of Kashmir and the north-east; a similar infrastructure of repression was installed in central India after forest-dwelling tribal peoples revolted against the nexus of mining corporations and the state. The government's plan to spy on internet and phone connections makes the NSA's surveillance look highly responsible. Muslims have been imprisoned for years without trial on the flimsiest suspicion of "terrorism"; one of them, a Kashmiri, who had only circumstantial evidence against him, was rushed to the gallows last year, denied even the customary last meeting with his kin, in order to satisfy, as the supreme court put it, "the collective conscience of the people".

"People who were not born then," Robert Musil wrote in The Man Without Qualities of the period before another apparently abrupt collapse of liberal values, "will find it difficult to believe, but the fact is that even then time was moving faster than a cavalry camel … But in those days, no one knew what it was moving towards. Nor could anyone quite distinguish between what was above and what was below, between what was moving forward and what backward." One symptom of this widespread confusion in Musil's novel is the Viennese elite's weird ambivalence about the crimes of a brutal murderer called Moosbrugger. Certainly, figuring out what was above and what was below is harder for the parachuting foreign journalists who alighted upon a new idea of India as an economic "powerhouse" and the many "rising" Indians in a generation born after economic liberalisation in 1991, who are seduced by Modi's promise of the utopia of consumerism – one in which skyscrapers, expressways, bullet trains and shopping malls proliferate (and from which such eyesores as the poor are excluded).

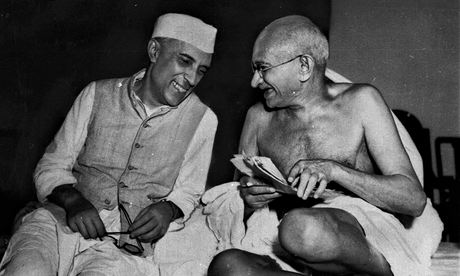

A civilising mission … Jawaharlal Nehru with Mahatma Gandhi. Photograph: Max Desfor/AP

A civilising mission … Jawaharlal Nehru with Mahatma Gandhi. Photograph: Max Desfor/AP

❦

People who were born before 1991, and did not know what time was moving towards, might be forgiven for feeling nostalgia for the simpler days of postcolonial idealism and hopefulness – those that Seth evokes in A Suitable Boy. Set in the 1950s, the novel brims with optimism about the world's most audacious experiment in democracy, endorsing the Nehruvian "idea of India" that seems flexible enough to accommodate formerly untouchable Hindus (Dalits) and Muslims as well as the middle-class intelligentsia. The novel's affable anglophone characters radiate the assumption that the sectarian passions that blighted India during its partition in 1947 will be defused, secular progress through science and reason will eventually manifest itself, and an enlightened leadership will usher a near-destitute people into active citizenship and economic prosperity.

India's first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, appears in the novel as an effective one-man buffer against Hindu chauvinism. "The thought of India as a Hindu state, with its minorities treated as second-class citizens, sickened him." In Nehru's own vision, grand projects such as big dams and factories would bring India's superstitious masses out of their benighted rural habitats and propel them into first-world affluence and rationality. The Harrow- and Cambridge-educated Indian leader had inherited from British colonials at least part of their civilising mission, turning it into a national project to catch up with the industrialised west. "I was eager and anxious," Nehru wrote of India, "to change her outlook and appearance and give her the garb of modernity." Even the "uninteresting" peasant, whose "limited outlook" induced in him a "feeling of overwhelming pity and a sense of ever-impending tragedy" was to be present at what he called India's "tryst with destiny".

That long attempt by India's ruling class to give the country the "garb of modernity" has produced, in its sixth decade, effects entirely unanticipated by Nehru or anyone else: intense politicisation and fierce contests for power together with violence, fragmentation and chaos, and a concomitant longing for authoritarian control. Modi's image as an exponent of discipline and order is built on both the successes and failures of the ancien regime. He offers top-down modernisation, but without modernity: bullet trains without the culture of criticism, managerial efficiency without the guarantee of equal rights. And this streamlined design for a new India immediately entices those well-off Indians who have long regarded democracy as a nuisance, recoiled from the destitute masses, and idolised technocratic, if despotic, "doers" like the first prime minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew.

But then the Nehruvian assumption that economic growth plotted and supervised by a wise technocracy would also bring about social change was also profoundly undemocratic and self-serving. Seth's novel, along with much anglophone literature, seems, in retrospect, to have uncritically reproduced the establishment ideology of English-speaking and overwhelmingly upper-caste Hindus who gained most from state-planned economic growth: the Indian middle class employed in the public sector, civil servants, scientists and monopolist industrialists. This ruling class's rhetoric of socialism disguised its nearly complete monopoly of power. As DR Nagaraj, one of postcolonial India's finest minds, pointed out, "the institutions of capitalism, science and technology were taken over by the upper castes". Even today, businessmen, bureaucrats, scientists, writers in English, academics, thinktankers, newspaper editors, columnists and TV anchors are disproportionately drawn from among the Hindu upper-castes. And, as Sen has often lamented, their "breathtakingly conservative" outlook is to be blamed for the meagre investment in health and education – essential requirements for an equitable society as well as sustained economic growth – that put India behind even disaster-prone China in human development indexes, and now makes it trail Bangladesh.

Dynastic politics froze the Congress party into a network of patronage, delaying the empowerment of the underprivileged Indians who routinely gave it landslide victories. Nehru may have thought of political power as a function of moral responsibility. But his insecure daughter, Indira Gandhi, consumed by Nixon-calibre paranoia, turned politics into a game of self-aggrandisement, arresting opposition leaders and suspending fundamental rights in 1975 during a nationwide "state of emergency". She supported Sikh fundamentalists in Punjab (who eventually turned against her) and rigged elections in Muslim-majority Kashmir. In the 1980s, the Congress party, facing a fragmenting voter base, cynically resorted to stoking Hindu nationalism. After Indira Gandhi's assassination by her bodyguards in 1984, Congress politicians led lynch mobs against Sikhs, killing more than 3,000 civilians. Three months later, her son Rajiv Gandhi won elections with a landslide. Then, in another eerie prefiguring of Modi's methods, Gandhi, a former pilot obsessed with computers, tried to combine technocratic rule with soft Hindutva.

The Bharatiya Janata party (BJP), a political offshoot of the RSS that Nehru had successfully banished into the political wilderness, turned out to be much better at this kind of thing. In 1990, its leader LK Advani rode a "chariot" (actually a rigged-up Toyota flatbed truck) across India in a Hindu supremacist campaign against the mosque in Ayodhya. The wildfire of anti-Muslim violence across the country reaped immediate electoral dividends. (In old photos, Modi appears atop the chariot as Advani's hawk-eyed understudy). Another BJP chieftain ventured to hoist the Indian tricolour in insurgent Kashmir. (Again, the bearded man photographed helping his doddery senior taunt curfew-bound Kashmiris turns out to be the young Modi.) Following a few more massacres, the BJP was in power in 1998, conducting nuclear tests and fast-tracking the programme of economic liberalisation started by the Congress after a severe financial crisis in 1991.

The Hindu nationalists had a ready consumer base for their blend of chauvinism and marketisation. With India's politics and economy reaching an impasse, which forced many of their relatives to emmigrate to the US, and the Congress facing decline, many powerful Indians were seeking fresh political representatives and a new self-legitimising ideology in the late 1980s and 90s. This quest was fulfilled by, first, both the post-cold war dogma of free markets and then an openly rightwing political party that was prepared to go further than the Congress in developing close relations with the US (and Israel, which, once shunned, is now India's second-biggest arms supplier after Russia). You can only marvel today at the swiftness with which the old illusions of an over-regulated economy were replaced by the fantasies of an unregulated one.

Narendra Modi waves to supporters as he rides on an open truck on his way to filing his nomination papers. Photograph: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

Narendra Modi waves to supporters as he rides on an open truck on his way to filing his nomination papers. Photograph: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

❦

Nehru's programme of national self-strengthening had included, along with such ideals as secularism, socialism and non-alignment, a deep-rooted suspicion of American foreign policy and economic doctrines. In a stunning coup, India's postcolonial project was taken over, as Octavio Paz once wrote of the Mexican revolution, "by a capitalist class made in the image and likeness of US capitalism and dependent upon it". A new book by Anita Raghavan, The Billionaire's Apprentice: The Rise of the Indian-American Elite and the Fall of the Galleon Hedge Fund, reveals how well-placed men such as Rajat Gupta, the investment banker recently convicted for insider trading in New York, expedited close links between American and Indian political and business leaders.

India's upper-caste elite transcended party lines in their impassioned courting of likely American partners. In 2008, an American diplomat in Delhi was given an exclusive preview by a Congress party factotum of two chests containing $25m in cash – money to bribe members of parliament into voting for a nuclear deal with the US. Visiting the White House later that year, Singh blurted out to George W Bush, probably resigned by then to being the most despised American president in history, that "the people of India love you deeply". In a conversation disclosed by WikiLeaks, Arun Jaitley, a senior leader of the BJP who is tipped to be finance minister in Modi's government, urged American diplomats in Delhi to see his party's anti-Muslim rhetoric as "opportunistic", a mere "talking point" and to take more seriously his own professional and emotional links with the US.