‘Viktor Orbán has long sought to rule Hungary as an autocrat, but the pandemic gave him his chance, allowing him to brand anyone standing in his way as unwilling to help the leader fight a mortal threat.’ Photograph: Tamás Kovács/AFP via Getty Images

Under the cover of coronavirus, all kinds of wickedness are happening. Where you and I see a global health crisis, the world’s leading authoritarians, fearmongers and populist strongmen have spotted an opportunity – and they are seizing it.

Of course, neither left nor right has a monopoly on the truism that one should never let a good crisis go to waste. Plenty of progressives share that conviction, firm that the pandemic offers a rare chance to reset the way we organise our unequal societies, our clogged cities, our warped relationship to the natural world. But there are others – and they tend to be in power – who see this opening very differently. For them, the virus suddenly makes possible action that in normal times would exact a heavy cost. Now they can strike while the world looks the other way.

For some, Covid-19 itself is the weapon of choice. Witness the emerging evidence that Bashar al-Assad in Damascus and Xi Jinping in Beijing are allowing the disease to wreak havoc among those groups whom the rulers have deemed to be unpersons, their lives unworthy of basic protection. Assad is deliberately leaving Syrians in opposition-held areas more vulnerable to the pandemic, according to Will Todman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies. As he puts it: “Covid-19 has provided Assad a new opportunity to instrumentalize suffering.”

Meanwhile, China continues to hold 1 million Uighur Muslims in internment camps, where they contend now not only with inhuman conditions but also a coronavirus outbreak. Those camps are cramped, lack adequate sanitation and have poor medical facilities: the virus couldn’t ask for a better breeding ground. What’s more, Uighur Muslims are reportedly being forced to work as labourers, filling in for non-Muslims who are allowed to stay home and protect themselves. That, according to one observer, “is reflective of how the Republic of China views [Uighur Muslims] as nothing but disposable commodities”.

Elsewhere, the pandemic has allowed would-be dictators an excuse to seize yet more power. Enter Viktor Orbán of Hungary, whose response to coronavirus was immediate: he persuaded his pliant parliament to grant him the right to rule by decree. Orbán said he needed emergency powers to fight the dreaded disease, but there is no time limit on them; they will remain his even once the threat has passed. They include the power to jail those who “spread false information”. Naturally, that’s already led to a crackdown on individuals guilty of nothing more than posting criticism of the government on Facebook. Orbán has long sought to rule Hungary as an autocrat, but the pandemic gave him his chance, allowing him to brand anyone standing in his way as unwilling to help the leader fight a mortal threat.

Xi has not missed that same trick, using coronavirus to intensify his imposition of China’s Orwellian “social credit” system, whereby citizens are tracked, monitored and rated for their compliance. Now that system can include health and, thanks to the virus, much of the public ambivalence that previously existed towards it is likely to melt away. After all, runs the logic, good citizens are surely obliged to give up even more of their autonomy if it helps save lives.

For many of the world’s strongmen, though, coronavirus doesn’t even need to be an excuse. Its chief value is the global distraction it has created, allowing unprincipled rulers to make mischief when natural critics at home and abroad are preoccupied with the urgent business of life and death.

Donald Trump gets plenty of criticism for his botched handling of the virus, but while everyone is staring at the mayhem he’s creating with one hand, the other is free to commit acts of vandalism that go all but undetected. This week the Guardian reported how the pandemic has not slowed the Trump administration’s steady and deliberate erosion of environmental protections. During the lockdown, Trump has eased fuel-efficiency standards for new cars, frozen rules for soot air pollution, continued to lease public property to oil and gas companies, and advanced a proposal on mercury pollution from power plants that could make that easier too. Oh, and he’s also relaxed reporting rules for polluters.

Trump’s Brazilian mini-me, Jair Bolsonaro, has outstripped his mentor. Not content with mere changes to the rulebook, he’s pushed aside the expert environmental agencies and sent in the military to “protect” the Amazon rainforest. I say “protect” because, as NBC News reported this week, satellite imagery shows “deforestation of the Amazon has soared under cover of the coronavirus”. Destruction in April was up by 64% from the same month a year ago. The images reveal an area of land equivalent to 448 football fields, stripped bare of trees – this in the place that serves as the lungs of the earth. If the world were not consumed with fighting coronavirus, there would have been an outcry. Instead, and in our distraction, those trees have fallen without making a sound.

Another Trump admirer, India’s Narendra Modi, has seen the same opportunity identified by his fellow ultra-nationalists. Indian police have been using the lockdown to crack down on Muslim citizens and their leaders “indiscriminately”, according to activists. Those arrested or detained struggle to get access to a lawyer, given the restrictions on movement. Modi calculates that majority opinion will back him, as rightist Hindu politicians brand the virus a “Muslim disease” and pro-Modi TV stations declare the nation to be facing a “corona jihad”.

In Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu – who can claim to have been Trumpist before Trump – has been handed a political lifeline by the virus, luring part of the main opposition party into a government of national unity that will keep him in power and, he hopes, out of the dock on corruption charges. His new coalition is committed to a programme that would see Israel annex major parts of the West Bank, permanently absorbing into itself territory that should belong to a future Palestinian state, with the process starting in early July. Now, the smart money suggests we should be cautious: that it suits Netanyahu to promise/threaten annexation more than it does for him to actually do it. Even so, in normal times the mere prospect of such an indefensible move would represent an epochal shift, high on the global diplomatic agenda. In these abnormal times, it barely makes the news.

Robin Niblett, director of Chatham House, argues that many of the global bad guys are, in fact, “demonstrating their weakness rather than strength” – that they are all too aware that if they fail to keep their citizens alive, their authority will be shot. He notes Vladimir Putin’s forced postponement of the referendum that would have kept him in power in Russia at least until 2036. When that vote eventually comes, says Niblett, Putin will go into it diminished by his failure to smother the virus.

Still, for now, the pandemic has been a boon to the world’s authoritarians, tyrants and bigots. It has given them what they crave most: fear and the cover of darkness.

Under the cover of coronavirus, all kinds of wickedness are happening. Where you and I see a global health crisis, the world’s leading authoritarians, fearmongers and populist strongmen have spotted an opportunity – and they are seizing it.

Of course, neither left nor right has a monopoly on the truism that one should never let a good crisis go to waste. Plenty of progressives share that conviction, firm that the pandemic offers a rare chance to reset the way we organise our unequal societies, our clogged cities, our warped relationship to the natural world. But there are others – and they tend to be in power – who see this opening very differently. For them, the virus suddenly makes possible action that in normal times would exact a heavy cost. Now they can strike while the world looks the other way.

For some, Covid-19 itself is the weapon of choice. Witness the emerging evidence that Bashar al-Assad in Damascus and Xi Jinping in Beijing are allowing the disease to wreak havoc among those groups whom the rulers have deemed to be unpersons, their lives unworthy of basic protection. Assad is deliberately leaving Syrians in opposition-held areas more vulnerable to the pandemic, according to Will Todman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies. As he puts it: “Covid-19 has provided Assad a new opportunity to instrumentalize suffering.”

Meanwhile, China continues to hold 1 million Uighur Muslims in internment camps, where they contend now not only with inhuman conditions but also a coronavirus outbreak. Those camps are cramped, lack adequate sanitation and have poor medical facilities: the virus couldn’t ask for a better breeding ground. What’s more, Uighur Muslims are reportedly being forced to work as labourers, filling in for non-Muslims who are allowed to stay home and protect themselves. That, according to one observer, “is reflective of how the Republic of China views [Uighur Muslims] as nothing but disposable commodities”.

Elsewhere, the pandemic has allowed would-be dictators an excuse to seize yet more power. Enter Viktor Orbán of Hungary, whose response to coronavirus was immediate: he persuaded his pliant parliament to grant him the right to rule by decree. Orbán said he needed emergency powers to fight the dreaded disease, but there is no time limit on them; they will remain his even once the threat has passed. They include the power to jail those who “spread false information”. Naturally, that’s already led to a crackdown on individuals guilty of nothing more than posting criticism of the government on Facebook. Orbán has long sought to rule Hungary as an autocrat, but the pandemic gave him his chance, allowing him to brand anyone standing in his way as unwilling to help the leader fight a mortal threat.

Xi has not missed that same trick, using coronavirus to intensify his imposition of China’s Orwellian “social credit” system, whereby citizens are tracked, monitored and rated for their compliance. Now that system can include health and, thanks to the virus, much of the public ambivalence that previously existed towards it is likely to melt away. After all, runs the logic, good citizens are surely obliged to give up even more of their autonomy if it helps save lives.

For many of the world’s strongmen, though, coronavirus doesn’t even need to be an excuse. Its chief value is the global distraction it has created, allowing unprincipled rulers to make mischief when natural critics at home and abroad are preoccupied with the urgent business of life and death.

Donald Trump gets plenty of criticism for his botched handling of the virus, but while everyone is staring at the mayhem he’s creating with one hand, the other is free to commit acts of vandalism that go all but undetected. This week the Guardian reported how the pandemic has not slowed the Trump administration’s steady and deliberate erosion of environmental protections. During the lockdown, Trump has eased fuel-efficiency standards for new cars, frozen rules for soot air pollution, continued to lease public property to oil and gas companies, and advanced a proposal on mercury pollution from power plants that could make that easier too. Oh, and he’s also relaxed reporting rules for polluters.

Trump’s Brazilian mini-me, Jair Bolsonaro, has outstripped his mentor. Not content with mere changes to the rulebook, he’s pushed aside the expert environmental agencies and sent in the military to “protect” the Amazon rainforest. I say “protect” because, as NBC News reported this week, satellite imagery shows “deforestation of the Amazon has soared under cover of the coronavirus”. Destruction in April was up by 64% from the same month a year ago. The images reveal an area of land equivalent to 448 football fields, stripped bare of trees – this in the place that serves as the lungs of the earth. If the world were not consumed with fighting coronavirus, there would have been an outcry. Instead, and in our distraction, those trees have fallen without making a sound.

Another Trump admirer, India’s Narendra Modi, has seen the same opportunity identified by his fellow ultra-nationalists. Indian police have been using the lockdown to crack down on Muslim citizens and their leaders “indiscriminately”, according to activists. Those arrested or detained struggle to get access to a lawyer, given the restrictions on movement. Modi calculates that majority opinion will back him, as rightist Hindu politicians brand the virus a “Muslim disease” and pro-Modi TV stations declare the nation to be facing a “corona jihad”.

In Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu – who can claim to have been Trumpist before Trump – has been handed a political lifeline by the virus, luring part of the main opposition party into a government of national unity that will keep him in power and, he hopes, out of the dock on corruption charges. His new coalition is committed to a programme that would see Israel annex major parts of the West Bank, permanently absorbing into itself territory that should belong to a future Palestinian state, with the process starting in early July. Now, the smart money suggests we should be cautious: that it suits Netanyahu to promise/threaten annexation more than it does for him to actually do it. Even so, in normal times the mere prospect of such an indefensible move would represent an epochal shift, high on the global diplomatic agenda. In these abnormal times, it barely makes the news.

Robin Niblett, director of Chatham House, argues that many of the global bad guys are, in fact, “demonstrating their weakness rather than strength” – that they are all too aware that if they fail to keep their citizens alive, their authority will be shot. He notes Vladimir Putin’s forced postponement of the referendum that would have kept him in power in Russia at least until 2036. When that vote eventually comes, says Niblett, Putin will go into it diminished by his failure to smother the virus.

Still, for now, the pandemic has been a boon to the world’s authoritarians, tyrants and bigots. It has given them what they crave most: fear and the cover of darkness.

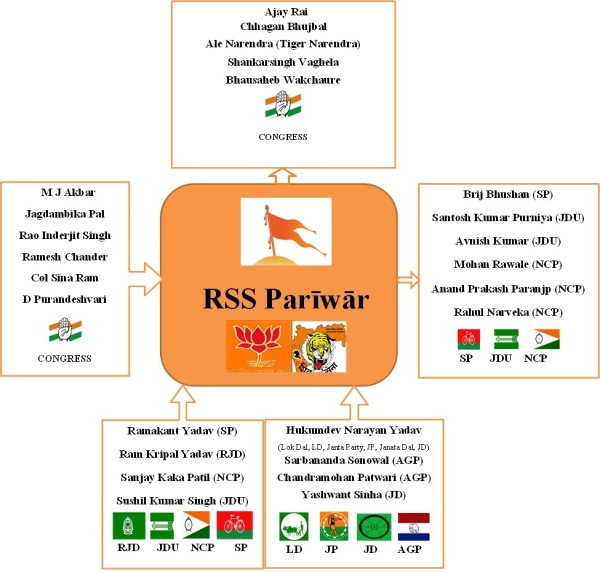

Flows between the RSS Parīwār and “Secular” Parties, Post-1947

Flows between the RSS Parīwār and “Secular” Parties, Post-1947