'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label victory. Show all posts

Showing posts with label victory. Show all posts

Saturday, 24 April 2021

Friday, 22 December 2017

Ye khel kya hai…. by Javed Akhtar

Mere mukhaalif ne chaal chal di hai

Aur ab

Meri chaal ke intezaar mein hai

Magar main kab se

Safed khaanon

Siyaah khaanon mein rakkhe

Kaale safed mohron ko dekhta hoon

Main sochta hoon

Ye mohre kya hain

Aur ab

Meri chaal ke intezaar mein hai

Magar main kab se

Safed khaanon

Siyaah khaanon mein rakkhe

Kaale safed mohron ko dekhta hoon

Main sochta hoon

Ye mohre kya hain

Agar main samjhoon

Ki ye jo mohre hain

Sirf lakdi ke hain khilone

To jeetna kya hai haarna kya

Na ye zaroori

Na vo aham hai

Agar khushi hai na jeetne ki

Na haarne ka bhi koi gham hai

To khel kya hai

Main sochta hoon

Jo khelna hai

To apne dil mein yaqeen kar lon

Ye mohre sach-much ke baadshah-o-vazeer

Sach-much ke hain piyaade

Aur in kea age hai

Dushmanon ki vo fauj

Rakhti hai jo mujh ko tabaah karne ke

Saare mansoobe

Sab iraade

Magar main aisa jo maan bhi loon

To sochta hoon

Yeh khel kab hai

Ye jang hai jis ko jeetna hai

Ye jang hai jis mein sab hai jaayaz

Koi ye kehta hai jaise mujh se

Ye jang bhi hai

Ye khel bhi hai

Ye jang hai par khiladiyon ki

Ye khel hai jang ki tarah ka

Main sochta hoon

Jo khel hai

Is mein ir tarah ka usool kyon hai

Ki koi mohra rah eke jaaye

Magar jo hai baadshah

Us par kabhi koi aanch bhi na aaye

Vazeer hi ko hai bas ijaazat

Ke jis taraf bhi vo chaahe jaaye

Ki ye jo mohre hain

Sirf lakdi ke hain khilone

To jeetna kya hai haarna kya

Na ye zaroori

Na vo aham hai

Agar khushi hai na jeetne ki

Na haarne ka bhi koi gham hai

To khel kya hai

Main sochta hoon

Jo khelna hai

To apne dil mein yaqeen kar lon

Ye mohre sach-much ke baadshah-o-vazeer

Sach-much ke hain piyaade

Aur in kea age hai

Dushmanon ki vo fauj

Rakhti hai jo mujh ko tabaah karne ke

Saare mansoobe

Sab iraade

Magar main aisa jo maan bhi loon

To sochta hoon

Yeh khel kab hai

Ye jang hai jis ko jeetna hai

Ye jang hai jis mein sab hai jaayaz

Koi ye kehta hai jaise mujh se

Ye jang bhi hai

Ye khel bhi hai

Ye jang hai par khiladiyon ki

Ye khel hai jang ki tarah ka

Main sochta hoon

Jo khel hai

Is mein ir tarah ka usool kyon hai

Ki koi mohra rah eke jaaye

Magar jo hai baadshah

Us par kabhi koi aanch bhi na aaye

Vazeer hi ko hai bas ijaazat

Ke jis taraf bhi vo chaahe jaaye

Main sochta hoon

Jo khel hai

Is mein is tarah ka usool kyon hai

Piyaada jab apne ghar se nikle

Palat ke vaapas na aane paaye

Main sochta hoon

Agar yahoo hai usool

To phir usool kya hai

Agar yahi hai ye khel

To phir ye khel kya hai

Main in savaalon se aane kab se ulajh raha hoon

Mere mukhalif ne chaal chal di hai

Aur ab meri chaal ke intezaar mein hai

Jo khel hai

Is mein is tarah ka usool kyon hai

Piyaada jab apne ghar se nikle

Palat ke vaapas na aane paaye

Main sochta hoon

Agar yahoo hai usool

To phir usool kya hai

Agar yahi hai ye khel

To phir ye khel kya hai

Main in savaalon se aane kab se ulajh raha hoon

Mere mukhalif ne chaal chal di hai

Aur ab meri chaal ke intezaar mein hai

The English translation is below:

What Game is It?

What Game is It?

My opponent has made a move

And now

Awaits mine.

But for ages

I stare at the black and white pieces

That lie on white and black squares

And I think

What are these pieces?

And now

Awaits mine.

But for ages

I stare at the black and white pieces

That lie on white and black squares

And I think

What are these pieces?

Were I to assume

That these pieces

Are no more than wooden toys

Then what is a victory or a loss?

If in winnings there are no joys

Nor sorrows in losing

What is the game?

I think

If I must play

Then I must believe

That these pieces are indeed king and minister

Indeed these are foot soldiers

And arrayed before them

Is that enemy army

Which harbours all plans evil

All schemes sinister

To destroy me

But were I to believe this

Then is this a game any longer?

This is a war that must be won

A war in which all is fair

It is as if somebody explains:

This is a war

And a game as well

It is a war, but between players

A game between warriors

I think

If it is a game

Then why does it have a rule

That whether a foot solder stays or goes

The one who is king

Must always be protected?

That only the minster has the freedom

To move any which way?

That these pieces

Are no more than wooden toys

Then what is a victory or a loss?

If in winnings there are no joys

Nor sorrows in losing

What is the game?

I think

If I must play

Then I must believe

That these pieces are indeed king and minister

Indeed these are foot soldiers

And arrayed before them

Is that enemy army

Which harbours all plans evil

All schemes sinister

To destroy me

But were I to believe this

Then is this a game any longer?

This is a war that must be won

A war in which all is fair

It is as if somebody explains:

This is a war

And a game as well

It is a war, but between players

A game between warriors

I think

If it is a game

Then why does it have a rule

That whether a foot solder stays or goes

The one who is king

Must always be protected?

That only the minster has the freedom

To move any which way?

I think

Why does this game

Have a rule

That once a foot solder leaves home

He can never return?

I think

If this is the rule

Then what is a rule?

If this is the game

Then what is the name of the game?

I have been wrestling for ages with these questions

But my opponent has made a move

And awaits mine.

Why does this game

Have a rule

That once a foot solder leaves home

He can never return?

I think

If this is the rule

Then what is a rule?

If this is the game

Then what is the name of the game?

I have been wrestling for ages with these questions

But my opponent has made a move

And awaits mine.

Tuesday, 3 May 2016

A CV of failure shows not every venture has a happy ending – and that’s OK

Julian Baggini in The Guardian

CV of failures: Princeton professor publishes résumé of his career lows

But the irony runs deeper. Haushofer probably would not have paraded his failures in the first place if he were not now a high-flying Princeton professor. Admitting to past defeats is easy if ultimately you have emerged the victor.

Haushofer’s confession has been praised as a breath of fresh air, a brave display of honesty. But sharing our past trials and tribulations is mainstream, not radical. No success story is complete without the chapter about overcoming adversity. Indeed, I often suspect that many people exaggerate their earlier problems in order to fit this standard narrative and if they don’t, others will do it for them. JK Rowling was a single mother on benefits, but others talked this up into a “rags to riches” fairy story. She has explicitly denied that she ever wrote in cafes to escape from an unheated flat, a story that never made much sense, given the price of a cappuccino in Edinburgh.

It is much harder to, if not celebrate, at least embrace failures when they are more than temporary setbacks. Would Hausfhofer have shared his list of rejections had they not been followed by acceptances? If so, he is braver and more honest than most. Increasingly our culture peddles the myth that with enough belief, determination, and perhaps even hard work, you can achieve anything you want. So if you do terminally fail, that can only mean that you have not tried, believed, or worked enough.

This is pernicious nonsense. The harder truth to accept is that success is never guaranteed. Luck plays its part, but there is also the simple fact that we do not know what we can achieve until we try. Success requires a happy coincidence of talent, effort and fortune, so if you try to do anything of any ambition, the possibility of failure is ever present. When our plans fail, there is no reason to think that necessarily reveals a deep failure in ourselves.

I’m not sure what I was thinking when I saved all those rejection letters. At the time, I didn’t know whether they would record mere setbacks or a thwarted ambition. But either way, they would have served a purpose. Had I not go on to have a writing career, they would have reminded me that I did at least try and that the reason I did not succeed was not for want of effort. That reminder would be sobering and humbling, which is why it would have been so valuable. If we are to go to our graves at peace with ourselves, we must be able to accept our disappointments and limitations as well as our successes.

Since I have gone on to earn my living by writing, I could wrongly take them to be proof of how my refusal to take no for an answer ensured that my talents were eventually recognised. The more honest way to see them is as evidence of how fortunate I was that eventually someone chose to take a punt on me.

In Hollywood, every failure simply serves to make the eventual success more inevitable. In real life, every past failure should be a reminder that a happy outcome was never guaranteed. Our failed relationships, terrible jobs and bad holidays reflect our characters and the reality of our lives at least as much as the good times, which often hang on a thread. Thinking more about our failures might just help us to be more grateful for the successes we enjoy and kinder to ourselves when, more often, they elude us.

‘JK Rowling was a single mother on benefits, but others talked this up into a rags to riches fairy story.’ Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Guardian

In my memory box I have a fine collection of rejection letters from editors and agents unimpressed with my first attempt at a book. Unsurprisingly, these mementoes of failure are the odd ones out in a collection that generally catalogues the highs rather than the lows of my life. We do not generally keep pictures of ex-partners from disastrous relationships on our mantelpieces, or photos of our sullen selves trapped inside a rain-swept, half-built motel.

But according to Princeton psychology professor Johannes Haushofer, we should do more to remember our failures. He has tweeted a CV of his setbacks, including lists of degree programmes he did not get into; papers that were rejected by journals; and academic positions, research funding and fellowships he did not get. Ironically, this little stunt has been a huge hit. “This darn CV of Failures has received way more attention that my entire body of academic work,” he said. Expect a TED talk and book to follow.

In my memory box I have a fine collection of rejection letters from editors and agents unimpressed with my first attempt at a book. Unsurprisingly, these mementoes of failure are the odd ones out in a collection that generally catalogues the highs rather than the lows of my life. We do not generally keep pictures of ex-partners from disastrous relationships on our mantelpieces, or photos of our sullen selves trapped inside a rain-swept, half-built motel.

But according to Princeton psychology professor Johannes Haushofer, we should do more to remember our failures. He has tweeted a CV of his setbacks, including lists of degree programmes he did not get into; papers that were rejected by journals; and academic positions, research funding and fellowships he did not get. Ironically, this little stunt has been a huge hit. “This darn CV of Failures has received way more attention that my entire body of academic work,” he said. Expect a TED talk and book to follow.

CV of failures: Princeton professor publishes résumé of his career lows

But the irony runs deeper. Haushofer probably would not have paraded his failures in the first place if he were not now a high-flying Princeton professor. Admitting to past defeats is easy if ultimately you have emerged the victor.

Haushofer’s confession has been praised as a breath of fresh air, a brave display of honesty. But sharing our past trials and tribulations is mainstream, not radical. No success story is complete without the chapter about overcoming adversity. Indeed, I often suspect that many people exaggerate their earlier problems in order to fit this standard narrative and if they don’t, others will do it for them. JK Rowling was a single mother on benefits, but others talked this up into a “rags to riches” fairy story. She has explicitly denied that she ever wrote in cafes to escape from an unheated flat, a story that never made much sense, given the price of a cappuccino in Edinburgh.

It is much harder to, if not celebrate, at least embrace failures when they are more than temporary setbacks. Would Hausfhofer have shared his list of rejections had they not been followed by acceptances? If so, he is braver and more honest than most. Increasingly our culture peddles the myth that with enough belief, determination, and perhaps even hard work, you can achieve anything you want. So if you do terminally fail, that can only mean that you have not tried, believed, or worked enough.

This is pernicious nonsense. The harder truth to accept is that success is never guaranteed. Luck plays its part, but there is also the simple fact that we do not know what we can achieve until we try. Success requires a happy coincidence of talent, effort and fortune, so if you try to do anything of any ambition, the possibility of failure is ever present. When our plans fail, there is no reason to think that necessarily reveals a deep failure in ourselves.

I’m not sure what I was thinking when I saved all those rejection letters. At the time, I didn’t know whether they would record mere setbacks or a thwarted ambition. But either way, they would have served a purpose. Had I not go on to have a writing career, they would have reminded me that I did at least try and that the reason I did not succeed was not for want of effort. That reminder would be sobering and humbling, which is why it would have been so valuable. If we are to go to our graves at peace with ourselves, we must be able to accept our disappointments and limitations as well as our successes.

Since I have gone on to earn my living by writing, I could wrongly take them to be proof of how my refusal to take no for an answer ensured that my talents were eventually recognised. The more honest way to see them is as evidence of how fortunate I was that eventually someone chose to take a punt on me.

In Hollywood, every failure simply serves to make the eventual success more inevitable. In real life, every past failure should be a reminder that a happy outcome was never guaranteed. Our failed relationships, terrible jobs and bad holidays reflect our characters and the reality of our lives at least as much as the good times, which often hang on a thread. Thinking more about our failures might just help us to be more grateful for the successes we enjoy and kinder to ourselves when, more often, they elude us.

Saturday, 14 June 2014

Welcome to Pseudo-Democracy – Unpacking the BJP Victory: Irfan Ahmad

MAY 25, 2014

tags: BJP victory 2014, Narendra Modi, RSS

by Nivedita Menon in Kafila

Guest Post by IRFAN AHMAD

This article offers a preliminary analysis of what the Modi phenomenon means in terms of BJP’s sweeping win on 16 May. It makes four propositions.

First, we stop seeing it as an individual phenomenon centered on the personality of Modi even as his votaries as well as some critics tend to view it that way.

Second, the Modi phenomenon is triumph of a massive ideological movement at the center of which stands the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh, RSS. Sharply distinguishing between the BJP and the RSS is a naivety; the RSS’ influence goes far beyond as numerous politicians under its influence have gone to the non-RSS parties in the same way as politicians from the non-RSS parties have joined the RSS-BJP collective.

Third, the BJP victory is neither due to development nor due to anti-corruption but due to Hindutva dressed as development so that both were rendered synonymous. The BJP victory, I contend, is an outcome of a violent mobilization against “the other”, Muslims.

Fourth, BJP’s victory is not the triumph of democracy but its subversion. Charting a different genealogy of demokratiain Greek, I argue how it is pseudo democracy.

As I explain these propositions, I request readers to be somewhat patient –they are a bit long, like the night of 16 May.

Charisma: Assembled, Loaded and Televised

In a live interview to a Singapore-based television channel on the final day of voting, I was asked what I thought of Modi as a “very charismatic person” and his track record of economic growth and delivery. Clearly, Modi’s charisma was no longer merely national; it was internationalized much like the profiteering McDonald as a brand. Such a ubiquity of wave or charisma of Modi entails understanding charisma afresh. For sociologist Max Weber, charisma means the belief among followers in a leader that he has an extraordinary quality as a gift from the grace of God. But how do followers think of someone as a leader in the first place? And how do they subsequently believe that the leader has charisma?

There is no inherent charisma; certainly, not in the 2014 elections. It was built brick by brick by turning corporate theft, ecological degradation and the state-supervised pogrom into development, silenced dissent into celebrated consensus, large crimes into even larger rallies of pride (recall gauraw yātrās). The charismatic leader saw corruption and showed corruption to people only in his rival parties but never told people about Bangaru Laxmans or B.S. Yedurappas and several others within the party whose corruption doesn’t even become a public issue. That is, charisma emanated from showing corruption outside while hiding it within. Yes, it required charisma to dub those speaking out against the state violence of 2002 as promoting divisiveness over development. These “conservatives” clung to the past while the charismatic leader wished to “move ahead” on the highway of future “development” he had already delivered.

In short, the transformation of political ugliness into a bumper sale of development with charismatic Modi at the center required much labor, creativity, coordination, manpower, involvement of internationally-trained professionals, production of comic books to inspire children through Modi’s personal life story and a gigantic sum of money. In one estimate Rs. 5,000 crore (over US $900 million Dollars) was spent on advertisement alone (EPW, 24 May, p.7) –at the rate of Rs. 20 per lunch, the entire population of India, 125 crore, would have enjoyed lunch for full two days. But still all these wouldn’t have mattered significantly if they were not televised by media which obediently did. It won’t be unreasonable to say, then, that Modi’s charisma is a gift from the grace of mammon, television, Google, social media and YouTube.

The Omnipresent Collective behind the Individual

If charisma is not an inherent quality dwelling within the individual – charisma of Vinoba Bhave the “saint” who engineered the Bhoodan movement and is considered one of the most charismatic leaders in independent India was enmeshed in an economic matrix and crafted by the massive political machinery and leaders of that time, Jawaharlal Nehru included (TK Oommen “Charisma, Social Structure and Change”, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 1967) –what is the political collective that explains Modi’s charisma? The answer is short: the RSS which has the explicit goal of making India into a Hindu state with Muslims as its prime foe. What was distinct about the 2014 elections was that RSS’ myriad organizations –in all age groups, across gender, every walk of life and every corner of India –swung into action on camera. Unlike in the past, the RSS and the BJP publicly and proudly acknowledged their mutual contributions. The mask that the RSS was just a cultural, not political, organization was cast off. So, the question if the BJP government would be remote-controlled by the RSS headquarters in Nagpur is redundant. A day after the victory, Uma Bharti, a senior BJP leader, told NDTV:

There shouldn’t be any hesitation (sankōch) in accepting that the RSS is our policy director (nītī nirdēshak). What they [the RSS] have taught us has got mixed in our blood. Therefore, they don’t even need to remind us [the BJP].There is no need for remote control [of the BJP by the RSS]. We have come under self-control through them. We too have begun to think the way they think. Therefore, there is no need for a remote control. Now the countrymen have put a stamp of approval on it [the RSS]. A swayamsewak of the RSS who has also been itsparchārak is set to become Prime Minister of the country… People themselves have accepted our ideology.

There is no further need to belabor this point for the Kafila readers. What needs to be stressed is that the influence of Hindutva is not limited to the RSS family for it goes far beyond and deeper. That the ideology of Hindutva –different from Hinduism as a religious tradition(s) prior to the Nineteenth century –is also shared by individuals in explicitly non-Hindutva parties and organizations has a longer history. KM Munshi (1887–1971) joined the Indian National Congress in 1929 and described himself as a Gandhian. While in the Congress, he had developed such close relations with the Hindu Mahasabha (HM) that many, including Bhai Premchand, ex-President of the HM, held that Munshi’s “ideas were just the same as that of the Hindu Mahasabha”. Munshi had also joined the akhāṛās, gymnasia, for “training our [Hindu] race in the art of self-defense”. Given his militancy, he was advised to leave the Congress. Later he established Akhand Hindustan Conference to become its President. That Munshi was a Hindu nationalist determined to reestablish the Hindu glory, calling Muslims “goondas”, foreigners, invaders and Islam constituting a dark chapter in India’s history, was manifest in his numerous writings. Well-known was also his friendship with the Hindutva ideologues: VD Savarkar, BS Moonje, and Shyama Prasad Mookerjee. Yet, in 1946, M.K. Gandhi asked Munshi to rejoin the Congress (Manu Bhagavan, “The Hindutva Underground”, Economic & Political Weekly, 2008).

Before I come to the post-colonial period, let me mention three other examples. Lala Lajpat Rai (1865–1928) resigned from the Congress to become the President of the Hindu Mahasabha in 1925. On Jawaharlal Nehru’s invitation Shyama Prasad Mookerjee (1901–1953), ex-President of the Hindu Mahasabha and founder of the Jana Sangh, predecessor of the BJP, joined the Cabinet Nehru formed after Partition. Pundit Madanmohan Malaviya (1861–1946), twice presidents of the Congress in 1909 and 1918, became the President of the Hindu Mahasabha in 1923 (Christophe Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalism Reader, 2006, pp.61–62). With Malaviya’s help, the RSS started its shākẖasat the Banaras Hindu University (Pralay Kanungo, RSS’S Tryst With Politics, 2002, p. 49).

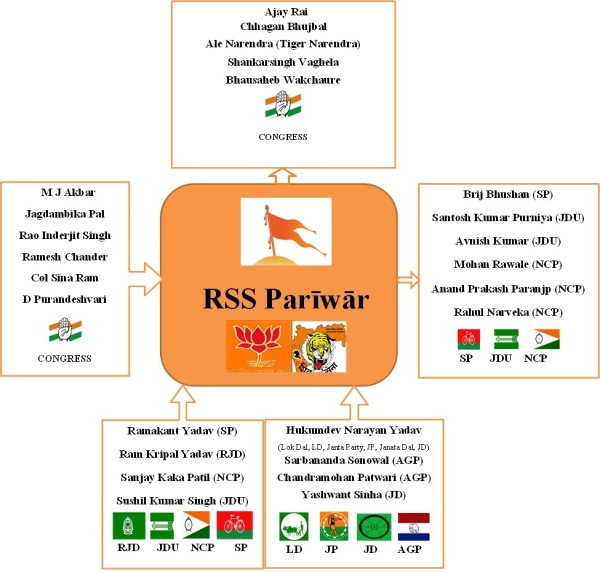

The crisscross between the RSS ideology/family and the non-RSS formations continued after 1947 as the table, by no means complete and based on individuals only (of more recent past) , shows below.

Flows between the RSS Parīwār and “Secular” Parties, Post-1947

Flows between the RSS Parīwār and “Secular” Parties, Post-1947

The flow between the RSS ideological camp and the non-RSS parties is epic, not episodic, enduring, not fleeting. It grows out of a sustained ideological groundwork to secure political equivalence. As the table above shows, Ajay Rai switched from the BJP to Samajwadi Party and then to the Congress to contest against Modi in Varanasi. Rarely did Rai ever critique the BJP or Modi. His sole claim against Modi and Arvind Kejriwal was that while his rivals were outsiders to Varanasi he alone was a local (asthānīye) candidate. In a special session of the Gujarat Assembly bidding farewell to Modi, on 21 May, Shankar Sinh Vaghela, Congress Leader of the Opposition not only praised Modi but asked him to build the Ram Temple at Ayodhya (obviously the Babri masjid is not even an issue). He also backed Modi and the BJP on other contentious issues. Friedrich Engels’ (d. 1895) remark that “the names of political parties are never entirely right” has some merit.

My point about the political equivalence is not an external attribution but the self-claim by the RSS which should be duly acknowledged as it is. When asked about the RSS appeal across political parties, Ram Madhav, the RSS spokesperson said in 2009:

We have our members in several political parties, including the Congress. We interact with them regularly…The BJP is closest to us in…ideology. Someone is 10 feet away from us; someone else is 1 km away, that’s the difference.

Responding to a similar question, Mohan Bhagwat, the new RSS Sarsanghchālak, head, offered more details:

Joining parties other than BJP depends on the individual thinking of a swayamsewak. And swayamsewaks are present in many parties. This I can tell you. Have you heard of Tiger Narendra in Andhra [Pradesh]? … Earlier he was in the BJP, now he is not [later Narendra became an MP from the Congress in 1999 and from Telangana Rashtra Samithi in 2004]… I had gone to Varanasi where the President of the city’s weyāpāri mandal was from the Samajwadi Party as well as the gẖatnāyak [group leader] of our shākẖa there. In the camp (mahāshīwir) of Agra many district-level workers of the BSP took part… We don’t count who is from which party or caste…We consider them all Hindus.

Hindutva as Development

It is against this wider backdrop of the organizational infrastructure and ideological apparatus that the claim by the BJP and the media that the latter won on the plank of development should be unpacked. To begin with, there is no single party which is opposed to development; every party vouches for development. So how did development and the BJP become synonymous? Consider Bihar under Nitish Kumar in alliance with the BJP. As long as this alliance was in place, Bihar was projected as a model of development next only to Gujarat. However, as the alliance broke in June 2013, we were told, Bihar’s development not only stopped but also declined. In March 2014, The Times of Indiareported that its GDP dramatically declined from 15.05% during 2012–13 to an estimated 8.82% during 2013–2014. While I am not an economist, this conclusion would be convincing if it also showed a major shift in the policy in less than a year and causally linked it to the decline. So, the message of The Times of India was plain: the BJP alone could guarantee development because after the breakup of alliance, development of Bihar drastically declined. The report was not about political economy. It was more about politics and less about economy.

When the alliance between Nitish Kumar and the BJP was intact, Bihar was also regarded as a well-administered state in terms of law and order, “good governance”, again only next to Gujarat. Soon after the dissolution of the alliance Bihar returned to jungle raj. Giriraj Singh, a key Bihar BJP leader, said: “Since the breakup of alliance [between Nitish Kumar and the BJP] there is nothing called government…law and order [in Bihar]”.

The logic of development as a winning catalyst is flawed because in the states of Bihar and UP –from where the BJP won over 100 seats –the RSS-BJP had systematically manufactured an anti-Muslim polarization to consolidate the “Hindu Vote”. In UP it began with the Muzaffarnagar riots operationalized through an incident in Kaval village in August 2013 as a result of which over 50,000 Muslims were rendered as refugees living in various camps. In early January 2014, with some journalists-academics I visited many camps, including the village Kakra and the police station nearby. There was a perfect harmony in the accounts of villagers, police officials and Kakra chief (pradẖān). They all held that Muslims themselves burnt their houses and willingly left villages to claim compensation from the state government. They were “greedy”. So massive was this propaganda that the simple fact that the promised amount of compensation was far lower than the price of their lost land and properties didn’t matter. The police told us that they made every effort to arrest the culprits responsible for loot and arson but they could not find them. While in Kakra, we found the culpritsliving there without any fear; one of them saying that the police lacked courage to touch them. The Muzaffarnagar riots were preface to the 2014 elections which the BJP won.

Two months later, in October 2013, in Bihar too the anti-Muslim campaign began with the explosions in the Patna rally to be addressed by Modi. Soon after the blast, TV channels such as News 24 showed one Pankaj as culprit and police arresting him. Firstpost reported that Ramnarayan Singh, Vikas Singh and Munna Singh were suspects. Within hours, as Beyondheadlines noted, the narrative changed as did the names of the suspect. Suspects became Muslims and their names began to circulate on television screens. The National Investigation Agency arrested Aftab Alam from Muzaffarpur where my parents live. Though released after a few days, media was awash with equation between Islam and terrorism and both against India. The colony where Alam lived was described as “mini Pakistan” by local Hindi media as well as many people in the “civil society”. So terrorized were Muslims in Muzaffarpur that they stopped greeting Alam after his release. When I expressed my desire to meet Alam, many of my relatives advised me not to. I did meet him.

From the time of the Patna blast the political field was methodically mobilized along the religious lines as a result of which electorally Bihar was as productive to the BJP as was the UP after the Muzaffarnagar riots. It was precisely because of such a line of political enmity sharply drawn well before the elections with a specific electoral purpose that at their conclusion Modi said: “There is no enmity in democracy but there is competition”. Does not this appear like an affirmation through the crooked lane of denial?

Let me conclude this section on development with the statement of Uma Bharti. When asked if Modi would give priority to Hindutva over development, she said:

“Hindutva is breath of life (prān) of India… However, prān remains still in its place… Things which require maintenance are hands, feet and eyes –in other words, development”.

Faces of Pseudo Democracy: Terror of Mercy

A day before counting began Chetan Bhagat wrote a blog for The Times of India. Predicting that the BJP with “near boycott by the Muslim community” will win an “all-time high Hindu power”, he posed questions and answered them as follows:

What do the BJP and Indian majority do with this new Hindu power? Do we use it to settle scores with Muslims? Do we use it to establish a majoritarian, intolerant state where minorities are ‘put in their place’? Do we impose ourselves and say things like, ‘India is the land of Hindus’? Do we make laws more in line with Hindu religion?Frankly, we may have the power to do some of these things now. It may even appeal to sections of the population. However, be warned. This would be an awful and terrible use of this power. In the long term, such a thought process will only turn us into a conservative, regressive, unsafe and poor country where nobody would want to come for business (emphasis added).

While Bhagat’s questions are clear, his answers are not. Of the items listed in questions, in his answer he refers to “some of these things” leaving it for the readers “which ones”. What is clear, however, is that in warning about the terrible use of power, he brazenly violates the innate worth and dignity of humans and shows concern for them because “nobody would want to come for business”. Such a beastly urge –even beasts don’t have that –where treatment of humans (Muslims) is predicated on the calculations of profit and capital, is not a value for most followers of any religion, including Hinduism, in whose name Bhagat speaks. Bhagat’s vocabulary draws less from religion and more from its entanglement with supremacist nationalism and majoritarian democracy both of which must have been strangers to our forefathers in Vedic times. His invocation of the “Indian majority” which he equates with Hindus is a common, though flawed, understanding of democracy. Many dissenting with Bhagat’s lines of thinking, however, accept the idea of a Hindu majority but reject the BJP’s claim to represent all Hindus by arguing that two-thirds of them did not vote for it. Statistically, it is correct. Philosophically, it is not for it concedes the idea of an ethno majority as central to democracy.

Against the received wisdom political theorist Josiah Ober recently argued that the original meaning of demokratia in Greek is “capacity to do things, not majority rule”. In contrast to monarchia (monos: one) and oligarchia (hoi oligoi: the few), demokratia has no reference to number. It connotes a collective body of people. Since nowhere is any people monolithic, the capacity to do things would be diverse and multiple as would be the cultural goals and political idioms. The equation between democracy and majority rule was pejoratively done by Greek critics of democracy. Is it not strange that contemporary votaries of majority rule like Bhagat share grounds with ancient opponents of democracy? It is precisely this equivalence between democracy and the rule by majority where majority is construed as a distinct ethno that has caused massive violence across the globe. Theodore Roosevelt’s statement that “Extermination [of Indians] was ultimately as beneficial as it was inevitable” bears testimony to such a bloody notion of democracy.

Shortly before the build-up to the 2014 elections, Uma Bharti told Aaj Tak that “Only right-wing Hindutva leaders can be the savior of Muslims and guarantee their security. Only we can instill confidence and erode fear from the Muslim psyche”. On close reflections, it is not difficult to see that this grand assurance conceals a grander danger and threat. Like terror and mercy security and the very threat to that security are intimately connected; they are the cover and back page of the same book. To invoke Slavoj Žižek, “only a power which asserts its full terrorist…capacity to destroy anything and anyone it wants” can speak of “infinite mercy” by guaranteeing security to Muslims. Does a vocal democracy rob people of their capacity to do things and destine them to be no more than silent objects of securitization?

If not pseudo democracy, how should we name a feverish mobilization whose prime goal was to dismiss, silence, erase or subordinate everything so as to singularly secure Mission 272 plus and whose leader (Amit Shah) vowed to deliver 50 Plus in UP, this plus here and that plus there? If not pseudo democracy, how should we name an election where over 40 Muslims were killed in Assam for exercising their choice (to the killers, theirs was a wrong choice)? If not pseudo democracy, how should we name a polity whose authors like Chetan Bhagat impose cultural assimilation and oblige all those who object to assimilation to apply for “citizenship elsewhere” and who further give the Manichean choice for either “oil and water” or “milk and sugar” but omits the metaphor of a beautiful garden where flowers of all colors can bloom? If not pseudo democracy, how should we name a polity whose leaders like Uma Bharti present fear as freedom, threat as security, death as life and dark, deadly thorn as fresh, white rose?

Wednesday, 1 May 2013

Cricket and Causes - It's not about selection or tactics, silly

Understanding causes is incredibly difficult. It is much easier to assume that easily discernible surface issues are the primary explanations for victory and defeat

Ed Smith

May 1, 2013

| |||

Related Links

Ed Smith : What can colonoscopies teach us about cricket?

Players/Officials: Mike Atherton | Michael Clarke

| |||

If you want to understand sport, you have to understand causes. More accurately, you have to understand how difficult it is to be sure about which causes really influence events, and which are merely irrelevant side issues.

Coaching is about understanding causes: what causes players to perform better? Journalism is about causes: which factors led one team to beat the other? Fans, too, reflect obsessively about causes: what might make the difference for us next season? Sport, like history, is about causes.

And yet understanding causes is incredibly difficult. Causal threads must be observed and disentangled, then weighed and judged. It is much easier simply to assume that easily discernible surface issues - such as selection and short-term tactics - are the primary explanations for why teams win and lose.

That is why the books that have most influenced my thinking about sport address the question of causes rather than sport itself. If I had to name one book that anyone with a serious interest in sport should read, it would be Nassim Taleb's Fooled by Randomness. It scarcely mentions sport, and Taleb actively dislikes organised games. But Fooled by Randomness explores the dangers of sloppy assumptions about causality. It attacks lazy guesses about one thing "leading" to another. It makes the reader re-examine his own flawed reasoning.

Taleb recalls watching the financial markets on Bloomberg TV in December 2003. When Saddam Hussein was captured, the price of US treasury bills went up. The caption on TV explained that this price movement was "due to the capture of Saddam Hussein". Half an hour later, the price of US treasury bills went down. The TV caption explained that this was "due to the capture of Saddam Hussein".

The same "cause" had been invoked to "explain" two opposite effects, which is, obviously, logically impossible.

The next time you absorb sports punditry, keep in mind that story about Bloomberg TV and the price of Treasury bills. You will learn that a golfer misses a crucial putt "because he lost concentration", and then misses the next putt because he was "trying too hard". You will learn that a team loses one match "because they didn't stick to the game plan", then loses the next "because they were unable to think on their feet".

A manager messes up one match "because he was too loyal to his favourite players", then fails in the next "because he unnecessarily alienated the core of the team". And, my favourite: there is always the player who "benefits from utter single-mindedness" one week, and then "suffers from a damaging lack of perspective" the next.

The point, of course, is that causes are being manipulated to fit outcomes. They weren't causes at all, merely things that happened before the defeat. The ancient Romans had an ironic phrase for this terrible logic - post hoc, ergo propter hoc, "after this, therefore because of this".

It is hard to imagine a stronger contender for adopting false causes than the failure of English cricket teams to win the Ashes between 1987 and 2005. This dismal sequence was, apparently, "caused" by the following factors: structure of county cricket, unshaven stubbles worn by some England captains, sticking with a failing core of senior players for too long, introducing too many new players, being insufficiently hard-working and professional, being insufficiently joyful and amateur, having too many counties, being too English, not being English enough. And so on.

Pretty much anything that existed within English cricket, at some point or other, was used to explain England's lack of success in the Ashes. An English cricketer in the 1990s only had to brush his teeth to be told that they didn't do it like that in Australia.

Above all, English cricket failed because it was not like Australian cricket. If only England teams would copy Australian teams by (in no particular order): swearing/caring/sledging/bonding/singing/ drinking/attacking/being mates/taking risks/backing themselves/fronting up/digging in/manning up/playing for the badge/never saying die… if England teams simply did all that, then, frankly, playing Shane Warne's flipper and Glenn McGrath's metronomic seam-up would be a doddle.

| When your best is not quite good enough, the two levers under your control - selection and tactics - begin to look very inadequate. In other words, they are not really "causes" of defeat at all. They are simply things that happened along the way | |||

Imagine the logical gymnastics required when England started winning Ashes series again. All the previous causes of defeat had now to be converted into explanations for victory. If England's Ashes success continues, it can only be a matter of time until we have the ultimate "Bloomberg moment", when an article is written arguing that Australia routinely loses the Ashes because they have too few state sides and must urgently copy England's first-class structure of 18 counties.

True, some things within English cricket have changed in reality as well as perception: players are now centrally contracted to the England team, for example, rather than to their counties. But not as much has changed as is often claimed. Revolution - "chumps to champs" - is a snappier narrative than gradual evolution.

But the real fun lies elsewhere. It has now become fashionable to scour Australian cricket looking for "causes" of their decline. A few years ago, the personality of Michael Clarke became the focal point for critics of the culture within Australian cricket. When Clarke came good, it was time to look elsewhere for "causes" of muted Australian performances. Ex-players attacked selection as confused, even insulting. Australia, they argued, had to pick more young players, and yet had to pick more players with hard-earned experience; they had to stick with a consistent team while also, inevitably, abandoning obvious mistakes. Sound familiar?

Mike Atherton, the former England captain who received his fair share of criticism during the era of Australian dominance, remarked wryly this week: "It is not quite so easy to be bold, to be consistent or whatever else is deemed topical, when you are losing matches."

The two central variables in sport, the main levers controlled by the management, are selection and tactics. Imagine, for a moment, that you are in charge of the lesser of two teams. You pick what you think is your best XI. And you lose, despite the team playing at or near its potential. If you stick with the same team, are you not merely sleepwalking towards another defeat? And yet if you change it, what has led you to change your mind about the team that you thought was the best XI last week and which, after all, did not really under-perform? Difficult one, isn't it, picking a team that is less good than the opposition?

Now tactics. Imagine you devise what you consider to be your optimal tactical approach. You execute the plan reasonably well. And you lose. Do you change tactics, with the same logic that led you to change the team, or stick with the old tactics that led to defeat?

Very simply, when your best is not quite good enough, the two levers under your control - selection and tactics - begin to look very inadequate. In other words, they are not really "causes" of defeat at all. They are simply things that happened along the way.

It is the same with national economics. Governments and central banks control the familiar levers of interest rates, money supply and taxation. They are endlessly criticised for their handling of all three. But what if the actual economy, the thing itself, is simply not very robust? A rabbit cannot always be conjured magically from a hat.

I would not have explored all this if I wasn't surprised at how often it is forgotten or overlooked in the analysis of sport at every level, from the pub to the board room, and from the commentary box to the armchair. We have long accepted that understanding historical causes is profoundly subtle and intellectually demanding. Exactly the same applies to understanding causes in sport.

Wednesday, 7 December 2011

Winning is everything? Sorry, no

In cricket,

as in other sports, it's not about the statistics and the bottomline.

It's about how much joy you give, how well you are loved and remembered

Ed Smith

December 7, 2011

|

|||

|

Related Links

|

|||

Hundreds of thousands of men and women have played professional

football. None, surely, could have so fully lived up to the name

Socrates. He played as though football was a creative puzzle, to be

teased out like a philosophical enquiry. He played with grace but also

with lightness.

Not all of you may have encountered a mischievous theory called

nominative determinism. The idea is that people are predetermined to

pursue certain professions by their names: your name is your fate.

Britain's leading jurist is called Igor Judge (his professional billing

is "Judge Judge"); the world's fastest man is called Usain Bolt; and

"Dudus" Coke awaits trial in the US for allegedly running the Jamaican

drugs mafia.

Socrates certainly lived up to his nominative destiny. He was a

qualified doctor, a political activist and an independent thinker. His

attitude to life was appropriately philosophical. He knew that smoking

and drinking were damaging his health, but retorted, "It's a problem,

but we all have to die of something, don't we?"

The same joie de vivre informed Socrates' attitude to sport. He was unflinchingly committed to the joga bonito

- the beautiful game. "Beauty comes first. Victory is secondary. What

matters is joy." Even people who don't like football remember being

uplifted by Socrates' grace and audacity. They remember his mistakes as

well as his triumphs. They remember his movement and imagination as well

as his goals. And they remember that he was unique - perhaps the

highest accolade any sportsman can achieve. I almost forgot the most

important thing of all: he is remembered, full stop.

A great deal is written about greatness in sport. There is a natural

human urge to seek objectivity and proof about who is the greatest.

Averages are measured, metrics invented, comparisons fed through the

meat grinder of statistical analysis.

But statistics, I'm afraid, can never tell us the whole truth about

greatness. Because sporting achievement is not quite the same thing as

greatness. Look at cricket. Viv Richards was an exceptional performer in

Test cricket, but he wasn't off the map in terms of pure stats. Greg

Chappell and other contemporaries pushed him hard. But in terms of

greatness, Viv stood alone. The numbers don't quite capture the complete

Viv effect - not just on opponents but also on fans. Whenever I

remember watching him on television, a smile comes over my face - even

now, 25 years later.

Mark Waugh's Test match average was "only" 41 (that still sounds pretty

good to me, but it's undeniable that lots of players average 41 these

days). But the numbers don't reflect the pleasure he gave. A sublime

Waugh flick through midwicket was only worth four runs - the same as an

ugly thick edge from a lesser batsman - but it was worth much more to

those who paid money to watch.

Some of the most astonishing things Waugh did on a cricket field weren't

recorded at all. Greg Chappell tells a lovely story in his book The Making of Champions

about watching Waugh field on the footholds at extra cover and

midwicket in ODIs. The ball would be bouncing unpredictably on the

footholds and Waugh would swoop effortlessly and pick it up without

fumbling or diving, like a cat pouncing on a ball of string. Chappell

writes that he wanted to stand up and cheer every time. Statistically it

was an non-event. For the discerning fan, it was pure magic.

According to the averages, the racist cheat Ty Cobb was a better batter

than Babe Ruth. But Cobb was nowhere near as great a sportsman. Not if

we use the correct measurement: the extent to which he was loved and

remembered.

If you still think that winning in sport is all about the final score, I recommend reading Rafa: My Story,

the unflinchingly honest autobiography by Rafael Nadal. When he writes

about Roger Federer, his great rival, something strange happens to

Nadal. Rationally he knows that he has beaten Federer more often than

Federer has beaten him, but he insists that Federer is the greater

player. Partly, that is because Federer still possesses more grand

slams. But the deeper reason is that Nadal deeply respects - perhaps

even envies - the way Federer plays. "You get these blessed freaks of

nature in other sports, too."

| If you produce grim, boring and joyless sport, it is reassuring to fall back on the delusion that it is all in a worthy cause. Socrates knew better. He knew that sportsmen are entertainers | |||

Here is the interesting thing. Nadal does not congratulate himself for

being the more worthy champion. He congratulates Federer for the more

sublime talent. And Nadal may be right. In an era of wonderful tennis

players, Federer has been the most elegant, refined and instinctive.

Socrates' death has been described as a terrible day for sporting

romantics. In fact, it is a much sadder day for sporting

ultra-rationalists. Because the win-at-all-costs brigade has once again

been shown to be completely wrong. Socrates never won the World Cup, and

lost the biggest match of his career playing on his own terms. And how

is he remembered? As a loser? No. He is remembered with respect, with

adoration, with love. Over the long term, it is very simple: he won.

Remember Socrates' career and legacy the next time you hear "Winning

isn't everything; it's the only thing." That was American football coach

Vince Lombardi's dictum about sporting priorities. And in the 50 years

since Lombardi's quip, the reductionism of winning at all costs has

hardened into conventional wisdom.

Of course, it is a consoling thought - if you're a production-line

automaton incapable of playing sport creatively, or if you're a coach

determined to stamp out individuality and risk. Yes, if you produce

grim, boring and joyless sport, it is reassuring to fall back on the

delusion that it is all in a worthy cause.

Socrates knew better. He knew that sportsmen are entertainers. They must

try to win, too (no one is entertained by skill without will). But

entertainment is not bolted onto sport as an afterthought. It is at the

core of the whole project.

Professional athletes are only the temporary custodians of their sports.

Their highest calling is to pass it on to the next generation enhanced

rather than diminished. By that measure Socrates won - and he won big.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)