US tech innovators have a culture of regarding government as an innovation-blocking nuisance. But when Silicon Valley Bank collapsed, investors screamed for state protection writes John Naughton in The Guardian

So one day Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) was a bank, and then the next day it was a smoking hulk that looked as though it might bring down a whole segment of the US banking sector. The US government, which is widely regarded by the denizens of Silicon Valley as a lumbering, obsolescent colossus, then magically turned on a dime, ensuring that no depositors would lose even a cent. And over on this side of the pond, regulators arranged that HSBC, another lumbering colossus, would buy the UK subsidiary of SVB for the princely sum of £1.

Panic over, then? We’ll see. In the meantime it’s worth taking a more sardonic look at what went on.

The first thing to understand is that “Silicon Valley” is actually a reality-distortion field inhabited by people who inhale their own fumes and believe they’re living through Renaissance 2.0, with Palo Alto as the new Florence. The prevailing religion is founder worship, and its elders live on Sand Hill Road in San Francisco and are called venture capitalists. These elders decide who is to be elevated to the privileged caste of “founders”.

To achieve this status it is necessary to a) be male; b) have a Big Idea for disrupting something; and c) never have knowingly worn a suit and tie. Once admitted to the priesthood, the elders arrange for a large tipper-truck loaded with $100 bills to arrive at the new member’s door and cover his driveway with cash.

But this presents the new founder with a problem: where to store the loot while he is getting on with the business of disruption? Enter stage left one Gregory Becker, CEO of SVB and famous in the valley for being worshipful of founders and slavishly attentive to their needs. His company would keep their cash safe, help them manage their personal wealth, borrow against their private stock holdings and occasionally even give them mortgages for those $15m dream houses on which they had set what might loosely be called their hearts.

The most striking takeaway was the evidence produced by the crisis of the arrant stupidity of some of those involved

So SVB was awash with money. But, as programmers say, that was a bug not a feature. Traditionally, as Bloomberg’s Matt Levine points out, “the way a bank works is that it takes deposits from people who have money, and makes loans to people who need money”. SVB’s problem was that mostly its customers didn’t need loans. So the bank had all this customer cash and needed to do something with it. Its solution was not to give loans to risky corporate borrowers, but to buy long-dated, ostensibly safe securities like Treasury bonds. So 75% of SVB’s debt portfolio – nominally worth $95bn (£80bn) – was in those “held to maturity” assets. On average, other banks with at least $1bn in assets classified only 6% of their debt in this category at the end of 2022.

There was, however, one fly in this ointment. As every schoolboy (and girl) knows, when interest rates go up, the market value of long-term bonds goes down. And the US Federal Reserve had been raising interest rates to combat inflation. Suddenly, SVB’s long-term hedge started to look like a millstone. Moody’s, the rating agency, noticed and Mr Becker began frantically to search for a solution. Word got out – as word always does – and the elders on Sand Hill Road began to whisper to their esteemed founder proteges that they should pull their deposits out, and the next day they obediently withdrew $42bn. The rest, as they say, is recent history.

What can we infer about the culture of Silicon Valley from this shambles? Well, first up is its pervasive hypocrisy. Palo Alto is the centre of a microculture that regards the state as an innovation-blocking nuisance. But the minute the security of bank deposits greater than the $250,000 limit was in doubt, the screams for state protection were deafening. (In the end, the deposits were protected – by a state agency.) And when people started wondering why SVB wasn’t subjected to the “stress testing” imposed on big banks after the 2008 crash, we discovered that some of the most prominent lobbyists against such measures being applied to SVB-size institutions included that company’s own executives. What came to mind at that point was Samuel Johnson’s observation that “the loudest yelps for liberty” were invariably heard from the drivers of slaves.

But the most striking takeaway of all was the evidence produced by the crisis of the arrant stupidity of some of those involved. The venture capitalists whose whispered advice to their proteges triggered the fatal run must have known what the consequences would be. And how could a bank whose solvency hinged on assumptions about the value of long-term bonds be taken by surprise by the impact of interest-rate increases? All that was needed to model the risk was an intern with a spreadsheet. But apparently no such intern was available. Perhaps s/he was at Stanford doing a thesis on the Renaissance.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label capitalist. Show all posts

Showing posts with label capitalist. Show all posts

Sunday, 19 March 2023

Wednesday, 21 December 2016

Monday, 25 May 2015

How to turn a liberal hipster into a capitalist tyrant in one evening

Paul Mason in The Guardian

A worker in a Chinese clothing factory Photograph: Imaginechina/Corbis

A real Chinese sweatshop owner is playing a losing game against something much more sophisticated than the computer at the Young Vic: an intelligent machine made up of the smartphones of millions of migrant workers on their lunchbreak, plugging digitally into their village networks to find out wages and conditions elsewhere. That sweatshop owner is also playing against clients with an army of compliance officers, themselves routinely harassed by NGOs with secret cameras.

The whole purpose of this system of regulation – from above and below – is to prevent individual capitalists making short-term decisions that destroy the human and natural resources it needs to function. Capitalism is not just the selfish decisions of millions of people. It is those decisions sifted first through the all-important filter of regulation. It is, as late 20th-century social theorists understood, a mode of regulation, not just of production.

Yet it plays on us a cruel ideological trick. It looks like a spontaneous organism, to which government and regulation (and the desire of Chinese migrants to visit their families once a year) are mere irritants. In reality it needs the state to create and re-create it every day.

Banks create money because the state awards them the right to. Why does the state ram-raid the homes of small-time drug dealers, yet call in the CEOs of the banks whose employees commit multimillion-pound frauds for a stern ticking off over a tray of Waitrose sandwiches? Answer: because a company has limited liability status, created by parliament in 1855 after a political struggle.

World Factory … how would you cope? Photograph: photograph by David Sandison

The choices were stark: sack a third of our workforce or cut their wages by a third. After a short board meeting we cut their wages, assured they would survive and that, with a bit of cajoling, they would return to our sweatshop in Shenzhen after their two-week break.

But that was only the start. In Zoe Svendsen’s play World Factory at the Young Vic, the audience becomes the cast. Sixteen teams sit around factory desks playing out a carefully constructed game that requires you to run a clothing factory in China. How to deal with a troublemaker? How to dupe the buyers from ethical retail brands? What to do about the ever-present problem of clients that do not pay? Because the choices are binary they are rarely palatable. But what shocked me – and has surprised the theatre – is the capacity of perfectly decent, liberal hipsters on London’s south bank to become ruthless capitalists when seated at the boardroom table.

The classic problem presented by the game is one all managers face: short-term issues, usually involving cashflow, versus the long-term challenge of nurturing your workforce and your client base. Despite the fact that a public-address system was blaring out, in English and Chinese, that “your workforce is your vital asset” our assembled young professionals repeatedly had to be cajoled not to treat them like dirt.

And because the theatre captures data on every choice by every team, for every performance, I know we were not alone. The aggregated flowchart reveals that every audience, on every night, veers towards money and away from ethics.

Svendsen says: “Most people who were given the choice to raise wages – having cut them – did not. There is a route in the decision-tree that will only get played if people pursue a particularly ethical response, but very few people end up there. What we’ve realised is that it is not just the profit motive but also prudence, the need to survive at all costs, that pushes people in the game to go down more capitalist routes.”

In short, many people have no idea what running a business actually means in the 21st century. Yes, suppliers – from East Anglia to Shanghai – will try to break your ethical codes; but most of those giant firms’ commitment to good practice, and environmental sustainability, is real. And yes, the money is all important. But real businesses will take losses, go into debt and pay workers to stay idle in order to maintain the long-term relationships vital in a globalised economy.

Why do so many decent people, when asked to pretend they’re CEOs, become tyrants from central casting? Part of the answer is: capitalism subjects us to economic rationality. It forces us to see ourselves as cashflow generators, profit centres or interest-bearing assets. But that idea is always in conflict with something else: the non-economic priorities of human beings, and the need to sustain the environment. Though World Factory, as a play, is designed to show us the parallels between 19th-century Manchester and 21st-century China, it subtly illustrates what has changed.

The choices were stark: sack a third of our workforce or cut their wages by a third. After a short board meeting we cut their wages, assured they would survive and that, with a bit of cajoling, they would return to our sweatshop in Shenzhen after their two-week break.

But that was only the start. In Zoe Svendsen’s play World Factory at the Young Vic, the audience becomes the cast. Sixteen teams sit around factory desks playing out a carefully constructed game that requires you to run a clothing factory in China. How to deal with a troublemaker? How to dupe the buyers from ethical retail brands? What to do about the ever-present problem of clients that do not pay? Because the choices are binary they are rarely palatable. But what shocked me – and has surprised the theatre – is the capacity of perfectly decent, liberal hipsters on London’s south bank to become ruthless capitalists when seated at the boardroom table.

The classic problem presented by the game is one all managers face: short-term issues, usually involving cashflow, versus the long-term challenge of nurturing your workforce and your client base. Despite the fact that a public-address system was blaring out, in English and Chinese, that “your workforce is your vital asset” our assembled young professionals repeatedly had to be cajoled not to treat them like dirt.

And because the theatre captures data on every choice by every team, for every performance, I know we were not alone. The aggregated flowchart reveals that every audience, on every night, veers towards money and away from ethics.

Svendsen says: “Most people who were given the choice to raise wages – having cut them – did not. There is a route in the decision-tree that will only get played if people pursue a particularly ethical response, but very few people end up there. What we’ve realised is that it is not just the profit motive but also prudence, the need to survive at all costs, that pushes people in the game to go down more capitalist routes.”

In short, many people have no idea what running a business actually means in the 21st century. Yes, suppliers – from East Anglia to Shanghai – will try to break your ethical codes; but most of those giant firms’ commitment to good practice, and environmental sustainability, is real. And yes, the money is all important. But real businesses will take losses, go into debt and pay workers to stay idle in order to maintain the long-term relationships vital in a globalised economy.

Why do so many decent people, when asked to pretend they’re CEOs, become tyrants from central casting? Part of the answer is: capitalism subjects us to economic rationality. It forces us to see ourselves as cashflow generators, profit centres or interest-bearing assets. But that idea is always in conflict with something else: the non-economic priorities of human beings, and the need to sustain the environment. Though World Factory, as a play, is designed to show us the parallels between 19th-century Manchester and 21st-century China, it subtly illustrates what has changed.

A worker in a Chinese clothing factory Photograph: Imaginechina/Corbis

A real Chinese sweatshop owner is playing a losing game against something much more sophisticated than the computer at the Young Vic: an intelligent machine made up of the smartphones of millions of migrant workers on their lunchbreak, plugging digitally into their village networks to find out wages and conditions elsewhere. That sweatshop owner is also playing against clients with an army of compliance officers, themselves routinely harassed by NGOs with secret cameras.

The whole purpose of this system of regulation – from above and below – is to prevent individual capitalists making short-term decisions that destroy the human and natural resources it needs to function. Capitalism is not just the selfish decisions of millions of people. It is those decisions sifted first through the all-important filter of regulation. It is, as late 20th-century social theorists understood, a mode of regulation, not just of production.

Yet it plays on us a cruel ideological trick. It looks like a spontaneous organism, to which government and regulation (and the desire of Chinese migrants to visit their families once a year) are mere irritants. In reality it needs the state to create and re-create it every day.

Banks create money because the state awards them the right to. Why does the state ram-raid the homes of small-time drug dealers, yet call in the CEOs of the banks whose employees commit multimillion-pound frauds for a stern ticking off over a tray of Waitrose sandwiches? Answer: because a company has limited liability status, created by parliament in 1855 after a political struggle.

Our fascination with market forces blinds us to the fact that capitalism – as a state of being – is a set of conditions created and maintained by states. Today it is beset by strategic problems: debt- ridden, with sub-par growth and low productivity, it cannot unleash the true potential of the info-tech revolution because it cannot imagine what to do with the millions who would lose their jobs.

The computer that runs the data system in Svendsen’s play could easily run a robotic clothes factory. That’s the paradox. But to make a third industrial revolution happen needs something no individual factory boss can execute: the re-regulation of capitalism into something better. Maybe the next theatre game about work and exploitation should model the decisions of governments, lobbyists and judges, not the hapless managers.

The computer that runs the data system in Svendsen’s play could easily run a robotic clothes factory. That’s the paradox. But to make a third industrial revolution happen needs something no individual factory boss can execute: the re-regulation of capitalism into something better. Maybe the next theatre game about work and exploitation should model the decisions of governments, lobbyists and judges, not the hapless managers.

Saturday, 1 March 2014

"We Need Ambedkar--Now, Urgently..."

Saba Naqvi's interview of Arundhati Roy in Outlook India

In 1936, Dr B.R. Ambedkar was asked to deliver the annual lecture by the Hindu reformist group, the Jat-Pat-Todak Mandal (Forum for Break-up of Caste) in Lahore. When the hosts received the text of the speech, they found the contents “unbearable” and withdrew the invitation. Ambedkar then printed 1,500 copies of his speech at his own expense and it was soon translated into several languages. Annihilation of Caste would go on to have a cult readership among the Dalit community, but remains largely unread by the privileged castes for whom it was written.

Ambedkar’s landmark speech has now been carefully annotated and reprinted. What will certainly draw contemporary public attention to it is the essay written as an introduction by the Booker prize-winning author Arundhati Roy, titled The Doctor and the Saint.

Almost half of the 400-page book is Roy’s essay, the other half Annihilation of Caste. Roy writes about caste in contemporary India before getting into the Gandhi-Ambedkar stand-off. Taking off from what Ambedkar described as “the infection of imitation”, the domino effect of each caste dominating the ones lower down in the hierarchy, Roy says, “The ‘infection of imitation’, like the half-life of a radioactive atom, decays exponentially as it moves down the caste ladder, but never quite disappears. It has created what Ambedkar describes as the system of ‘graded inequality’ in which even the ‘low is privileged as compared with lower. Each class being privileged, every class is interested in maintaining the system’”.

However, the thrust of Roy’s powerful but disturbing essay deals with her exploration of the Gandhi-Ambedkar debate, and the man deified as the father of the nation does not come off well in this book. She writes: “Ambedkar was Gandhi’s most formidable adversary. He challenged him not just politically or intellectually, but also morally. To have excised Ambedkar from Gandhi’s story, which is the story we all grew up on, is a travesty. Equally, to ignore Gandhi while writing about Ambedkar is to do Ambedkar a disservice, because Gandhi loomed over Ambedkar’s world in myriad and un-wonderful ways.”

The Doctor and the Saint, your introduction to this new, annotated edition of Dr Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste, is also a deeply disturbing critique of Gandhi, especially to those of us for whom Gandhi is a loved and revered figure.

Yes, I know. It wasn’t easy to write it either. But in these times, when all of us are groping in the dark, despairing, and unable to understand why things are the way they are, I think revisiting this debate between Gandhi and Ambedkar, however disturbing it may be for some people, however much it disrupts old and settled patterns of thought, will actually, in the end, help illuminate our path. I think Annihilation of Caste is absolutely essential reading. Caste is at the heart of the rot in our society. Quite apart from what it has done to the subordinated castes, it has corroded the moral core of the privileged castes. We need Ambedkar—now, urgently.

Why should Gandhi figure so prominently in a book about Ambedkar? How did that come about?

Ambedkar was Gandhi’s most trenchant critic, not just politically and intellectually, but also morally. And that has just been written out of the mainstream narrative. It’s a travesty. I could not write an introduction to the book without addressing his debate with Gandhi, something which continues to have an immense bearing on us even today.

Annihilation of Caste is the text of a speech that Ambedkar never delivered. When the Jat-Pat-Todak Mandal, an offshoot of the Arya Samaj, saw the text and realised Ambedkar was going to launch a direct attack on Hinduism and its sacred texts, it withdrew its invitation. Ambedkar published the text as a pamphlet. Gandhi published a response to it in his magazineHarijan. But this exchange was only one part of a long and bitter conflict between the two of them...when I say that Ambedkar has been written out of the narrative, I’m not suggesting that he has been ignored; on the contrary, he is given a lot of attention—he’s either valorised as the ‘Father of the Constitution’ or ghettoised and then praised as a “leader of the untouchables”. But the anger and the passion that drove him is more or less airbrushed out of the story. I think that if we are to find a way out of the morass that we find ourselves in at present, we must take Ambedkar seriously. Dalits have known that for years. It’s time the rest of the country caught up with them.

Have you always held these views about Gandhi, or did you discover new aspects to him as you explored him vis-a-vis Ambedkar?

I am not naturally drawn to piety, particularly when it becomes a political manifesto. I mean, for heaven’s sake, Gandhi called eating a “filthy act” and sex a “poison worse than snake-bite”. Of course, he was prescient in his understanding of the toll that the Western idea of modernity and “development” was going to take on the earth and its inhabitants. On the other hand, his Doctrine of Trusteeship, in which he says that the rich should be left in possession of their wealth and be trusted to use it for the welfare of the poor—what we call Corporate Social Responsibility today—cannot possibly be taken seriously. His attitude to women has always made me uncomfortable. But on the subject of caste and Gandhi’s attitude towards it, I was woolly and unclear. Reading Annihilation of Caste prompted me to read Ambedkar’s What Congress and Gandhi Have Done to the Untouchables. I was very disturbed by that. I then began to read Gandhi—his letters, his articles in the papers—tracing his views on caste right from 1909 when he wrote his most famous tract, Hind Swaraj. In the months it took me to research and write The Doctor and the Saint I couldn’t believe some of the things I was reading. Look—Gandhi was a complex figure. We should have the courage to see him for what he really was, a brilliant politician, a fascinating, flawed human being—and those flaws were not to do with just his personal life or his role as a husband and father. If we want to celebrate him, we must have the courage to celebrate him for what he was. Not some imagined, constructed idea we have of him.

You could be accused of selectively picking out quotes from his writing to suit your own imagined, constructed idea of Gandhi....

When a man leaves behind 98 volumes of his Collected Works, what option does anybody have other than to be selective? Of course I have been selective, as selective as everybody else has been. And of course, those choices say a lot about the politics of the person who has done the selecting. My brief was to write an introduction to Annihilation of Caste. Reading Ambedkar made me realise how large Gandhi loomed in Ambedkar’s universe. When I read Gandhi’s pronouncements supporting the caste system, I wondered how his doctrine of non-violence and satyagraha could rest so comfortably on the foundation of a system which can be held in place only by the permanent threat of violence, and the frequent application of unimaginable violence. I grew curious about how Gandhi even came to be called a Mahatma.

I found that the first time he was publicly called Mahatma was in 1915, soon after he returned to India after spending 20 years in South Africa. What had he done in South Africa to earn him that honour?

That took me back to 1893, the year he first arrived in South Africa as a 24-year-old lawyer. I followed Gandhi’s writings about caste over a period of more than 50 years. So that answers questions like—“Did Gandhi change? And if so, how? Did he start off badly and grow into a Mahatma?” I wasn’t really researching Gandhi’s views on diet or natural cures, I was following the caste trail, and in the process I stumbled on the race trail, and eventually, through all the turbulence and mayhem, I found coherence. It all made sense.

It was consistent, and consistently disturbing. The fact is that whatever else he said and did, and however beautiful some of it was, he did say and write and do some very disturbing things. Those must be explained and accounted for. This applies to all of us, to everybody, sinner and saint alike. Let’s for the sake of argument imagine that someone driven by extreme prejudice ransacks the writings of Rabindranath Tagore. I am not a Tagore scholar, but I very much doubt that he or she would find letters, articles, speeches and interviews that are as worrying as some of the writings in the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi.

You say that Gandhi harboured attitudes that can only be described as racist towards the Blacks during his years in South Africa, you seem to see his positions as flawed and hypocritical. Would you agree with that?

I have not used those adjectives. I think you have inferred them from Gandhi’s speeches and writings reproduced in my introduction, which is perfectly understandable. Actually I don’t think Gandhi was a hypocrite. On the contrary, he was astonishingly frank. And I am impressed that all his writings, some of them—in my view at least—seriously incriminating, have been retained in the Collected Works.

That really is a courageous thing. I have written at length about Gandhi’s years in South Africa. I’ll just say a couple of things here about that period. First, the famous story about Gandhi’s political awakening to racism and imperialism because he was thrown out of a ‘whites only’ compartment in Pietermaritzberg is only half the story. The other half is that Gandhi was not opposed to racial segregation. Many of his campaigns in South Africa were for separate treatment of Indians. He only objected to Indians being treated on a par with ‘raw kaffirs’, which is what he called Black Africans. One of his first political victories was a ‘solution’ to the Durban post office ‘problem’. He successfully campaigned to have a third entrance opened so that Indians would not have to use the same door as the ‘kaffirs’. He worked with the British army in the Anglo-Boer war and during the crushing of the Bambatha rebellion. In his speeches he said he was looking forward to “an Imperial brotherhood”. And so it goes, the story. In 1913, after signing a settlement with the South African military leader Jan Smuts, Gandhi left South Africa. On his way back to India he stopped in London where he was awarded the Kaiser-e-Hind for public service to the British Empire. How did that add up to fighting racism and imperialism?

But ultimately he did fight imperialism, did he not? He led our country to freedom....

What was ‘freedom’ for some was, for others, nothing more than a transfer of power. Once again, I’d say the Gandhi-Ambedkar debate deepens and complicates our understanding of words like “imperialism” and “freedom”. In 1931, when Ambedkar met Gandhi for the first time, Gandhi questioned him about his sharp criticism of the Congress, which at the time amounted to criticising the struggle for the homeland. Ambedkar’s famous, and heart-breaking, reply was: “Gandhiji, I have no homeland. No untouchable worth the name would be proud of this land.”

Even after he returned from South Africa, Gandhi still saw himself as a ‘responsible’ subject of Empire. But in a few years, by the time of the first national non-cooperation movement, Gandhi had turned against the British. Millions of people rallied to his call, and though it would be incorrect to say that he alone led India to freedom from British rule, of course he played a stellar part. Yet in the struggle, though Gandhi spoke about equality and sometimes even sounded like a socialist, he never challenged traditional caste hierarchies or big zamindars.

Industrialists like the Birlas, the Tatas and the house of Bajaj bankrolled Gandhi’s political activity and he took care never to cross swords with them. Many of them had made a lot of money during the First World War, and had now come up against a glass ceiling.

They were irked and limited by British rule and by their own brushes with racism. So they threw their weight behind the national movement.

Around the time Gandhi returned from South Africa, mill workers who had not benefited from the managements’ windfall profits had become restive and there were a series of lightning strikes in the Ahmedabad mills. The mill-owners asked Gandhi to mediate. I have written about Gandhi’s interventions over the years in labour disputes, his handling of labour unions and his advice to workers about strikes—much of it is very puzzling. In other areas too, the famous Gandhian ‘pragmatism’ took some very strange turns. For example, in 1924, when villagers were protesting against the Mulshi Dam being built by the Tatas some distance away from Pune, to generate electricity for the Bombay mills, Gandhi wrote them a letter advising them to give up their protest. His logic is so very similar to the Supreme Court judgement of 2000 that allowed the construction of the World Bank-funded Sardar Sarovar Dam to proceed...so Ambedkar was spot-on when he said, “The question whether the Congress is fighting for freedom has very little importance as compared to the question for whose freedom is the Congress fighting?”

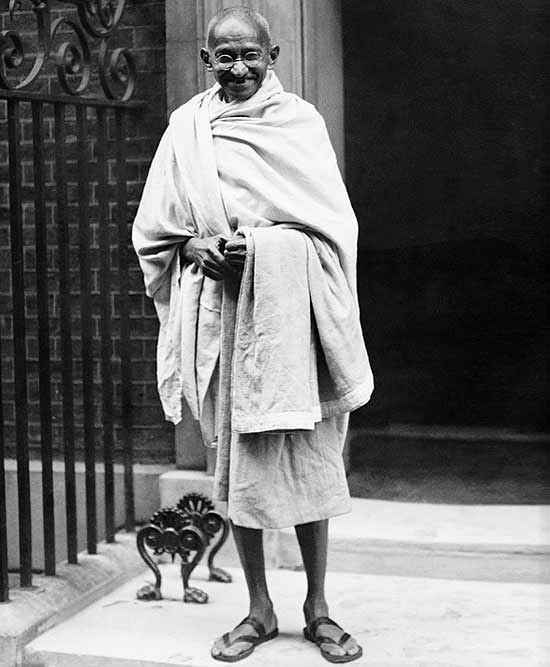

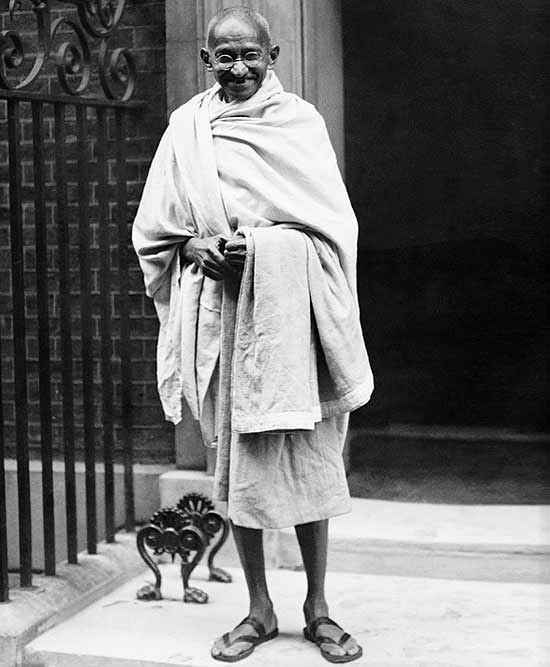

Photograph by Corbis, From Outlook 10 March 2014

In the past you have written powerful political essays based on reporting from the field or on contemporary events as they unfold. But in this work, you seem to have done some very serious historical research and drawn very different conclusions from many known historians who have worked on the national movement, Gandhi and Ambedkar. You are obviously going to be challenged. Do tell us about the journey that writing The Doctor and the Saint involved.

You say I’ll be challenged? Oh, and here I was imagining that it was me that was doing the challenging! Several years ago, S. Anand, the publisher of Navayana, gave me a spiral-bound copy of Annihilation of Caste and asked me if I would write an introduction to it. I read it and found it electrifying. But I was intimidated by the prospect of writing an introduction to it—a real introduction, not just some quotes patched together with praise and banalities. I didn’t feel that I was equipped to do that. I knew it would mean swimming through some pretty treacherous waters. Anand said he would wait, and he did.

Meanwhile, he began work on the annotations which placeAnnihilation of Caste in a context and make it an extraordinarily rich resource for scholars interested in the subject. I was writing fiction and had promised myself that I wasn’t going to write anything that involved footnotes anymore. But of course, when I started writing the introduction, given the way my argument developed, I had to reference almost every sentence. After a while I began to enjoy myself. The notes are not just references, they’re almost a parallel narrative, in and of themselves. I hope at least some people take the trouble to read them....

But coming back to your question of The Doctor and the Saintbeing a challenge—many historians have criticised Gandhi before, for other reasons, so I don’t think I am alone on this one at all. Many Dalits and Dalit scholars have, over the decades, been very sharply critical of Gandhi and Gandhism. Having said that, if this book begins another debate, a real debate, it can only be a good thing. I think it’s high time that there was one. I’m sure there are plenty of people who would be happy to weigh in on it.

Given what happened to Wendy Doniger’s book, are you worried?

Not about this book in particular, no. It’s Ambedkar’s book. But it’s true that we are becoming less and less free to write and say what we think. What the irreverent Mirza Ghalib could say in the 19th century about his relationship with Islam, what Saadat Hasan Manto could say about mullahs in the 1940s, what Ambedkar could say about Hinduism in the 1930s, what Nehru or JP could say about Kashmir—none of us can say today without risking our lives. The argument between Gandhi and Ambedkar that followed the publication of Annihilation of Caste was a harsh, intense debate between two extraordinary men—they were not afraid of real debate. Unlike contemporary bigots who demand book-banning, Gandhi—who found the text of Ambedkar’s speech disagreeable—actually wanted people to read it. He said, “No reformer can ignore the address.... It has to be read only because it is open to serious objection. Dr Ambedkar is a challenge to Hinduism.”

Your introduction begins with a powerful critique of the all-pervasive domination of traditional upper castes in the establishment, including the media, and you suggest that there has been a ‘project of unseeing’ across the political establishment. Don’t you think that the post-Mandal realities of contemporary India have actually made caste a fundamental unit of all politics?

When you look at India, through the prism of caste, at who controls the money, who owns the corporations, who owns the big media, who makes up the judiciary, the bureaucracy, who owns land, who doesn’t—contemporary India suddenly begins to look extremely un-contemporary. Caste was the engine that drove Indian society—not just Hindu society—much before the recommendations of the Mandal Commission. A long section of The Doctor and the Saint is an analysis of how, in the late 19th century, when the idea of ‘empire’ began to mutate into the idea of a ‘nation’, when the new ideas of governance and ‘representation’ arrived on our shores, it led to an immense anxiety about demography, about numbers. For centuries before that, millions of people who belonged to the subordinated castes—those who had been socially ostracised by privileged castes for thousands of years—had been converting to Islam, and later to Sikhism and Christianity to escape the stigma of their caste. But suddenly numbers began to matter. The almost fifty million “untouchables” became crucial in the numbers game. A raft of Hindu reformist outfits began to proselytise among them, to prevent conversion. The Arya Samaj started the Shuddhi movement—to ‘purify the impure’—to try and woo untouchables and Adivasis back into the ‘Hindu fold’. A version of that is still going on today with the VHP and the Bajrang Dal running their ‘Ghar Vapasi’ programmes in which Adivasi people are ‘purified’ and ‘returned’ to Hinduism. So yes, caste was, and continues to be, the fundamental unit of all politics in India.

So how can you call it a ‘project of unseeing’?

The ‘project of unseeing’ that I write about is something else altogether. It’s about the ways in which influential Indian intellectuals today, particularly those on the Left, for whom caste is just a footnote—an awkward, inconvenient appendage of reductive Marxist class analysis—have rendered caste invisible. To say “we don’t believe in caste” sounds nice and progressive. But it is either an act of evasion, or it comes from a position of such rarefied privilege where caste is not encountered at all. The ‘project of unseeing’ exists in almost all of our cultural practice—does Bollywood deal with it? Never. How many of our high-profile writers deal with it? Very few. Those who write about justice and identity, about the ill effects of neo-liberalism—how many address the issue of caste? Even some of our most militant people’s movements elide caste.

The Indian government’s churlish reaction to Dalits who wanted to be represented at the 2001 World Conference against racism in Durban is part of the ‘project of unseeing’. In the same way, the Indian census entirely elides caste in its data collection—leaving us all in the dark about what’s really going on—the scale of dispossession and violence against Dalits is part of the ‘project of unseeing’. Here’s something to think about—in 1919, during what came to be called ‘The Red Summer’ in the United States, approximately 165 Black people were killed. Almost one century later, in 2012 in India—the year of the Delhi gang-rape and murder—according to official statistics, 1,574 Dalit women were raped. And 651 Dalits were murdered. That’s just the criminal assault against Dalits. The economic assault, notwithstanding the emergence of a clutch of Dalit millionaires, is another matter altogether.

You say that caste in India—“one of the most brutal modes of hierarchical social organisation that human society has known—has managed to escape censure because it is so fused with Hinduism, and by extension with so much that is seen to be kind and good—mysticism, spiritualism, non-violence, tolerance, vegetarianism, Gandhi, yoga, backpackers, the Beatles—that, at least to outsiders, it seems impossible to pry it loose and try to understand it”. You argue that caste prejudice is on a par with racial discrimination and apartheid but has not been treated as such. Many would argue that electoral politics and reservation are adequate to deal with historical injustice. But recently a senior Congress leader, Janardhan Dwivedi, said reservation should be discontinued. How would you respond to such an argument?

It was an outrageous thing for anyone to say. Reservation is extremely important, and I have written at some length about it. To be eligible for the reservation policy, a Scheduled Caste person needs to have completed high school. Government figures say more than 70 per cent of Scheduled Caste students drop out before they matriculate. Which means for even low-end government jobs only one in every four Dalits is eligible. For a white-collar job, the minimum qualification is a graduate degree. Just over 2 per cent of Dalits are graduates. Even though it actually applies to so few, the reservation policy has meant that Dalits at least have some representation in the echelons of power. This is absolutely vital. Look at what one Ambedkar, who had the good fortune to get a scholarship to study in Columbia, managed to do. It is thanks to reservation that Dalits are now lawyers, doctors, scholars and civil servants. But even this little window of opportunity is resented and is under fire from the privileged. And the track record of government institutions, the judiciary, the bureaucracy and even supposedly progressive institutions like jnu in implementing reservation is appalling. There is only one government department in which Dalits are over-represented by a factor of six.

Almost 90 per cent of those designated as municipal sweepers—people who clean streets, who risk their lives to go down manholes and service the sewage system, who clean toilets and do menial jobs—are Dalits. Even this sector is up for privatisation now, which means private companies will be able to subcontract jobs on a temporary basis to Dalits for less pay and with no guarantee of job security. Of course there are problems with people getting fake certificates and so on. Those need to be addressed. But to use that to say reservation shouldn’t exist is ridiculous.

But surely you agree that the rise of Dalit parties like the BSP marks something close to a revolution in Indian democracy?

The rise of Dalit political parties has been a dazzling phenomenon.

But then our electoral politics, in the present shape, cannot really be revolutionary, can it? The book, and not just the introduction, deals with it in some detail. Ambedkar’s confrontation with Gandhi at the Second Round Table Conference in London in 1931 had precisely to do with that—with their very different views on the matter of political representation of and for Dalits.

Ambedkar believed that the right to representation was a basic right.

And all his life he fought for untouchables to have that right. He thought and wrote a great deal about the first-past-the-post electoral system and how untouchables would never be able to emerge from the domination of privileged castes in such a system because the population was scattered in a way that they would never form a majority in a political constituency. Gandhi, who worked among untouchables with missionary zeal, was not prepared to allow them to represent themselves. And he explicitly worked against that possibility. His Harijan Sevak Sangh—funded by G.D. Birla—which fronted the Temple Entry movement was made up only of privileged caste members. In the Mahajan Mazdoor Sangh, the mill workers’ union that Gandhi started in Ahmedabad, workers, many of whom were untouchables, were not allowed to be office-bearers, they were not allowed to represent themselves. At the Second Round Table Conference in London in 1931, Gandhi said, “I claim myself, in my own person, to represent the vast mass of untouchables.” In S. Anand’s note on the Poona Pact at the back of the book, he writes of how Gandhi, in a reply to a question from an untouchable member of the Congress party asking if he would ensure that Harijans were represented in state councils and panchayat boards, said the principle was “dangerous”.

Gandhi played a great part in seeing to it that Ambedkar’s project of developing untouchables into a political community that was aware of its rights, that could choose its own representatives from among themselves, was thwarted and undermined. Even today Dalits are paying the price for that. Despite these odds, the Bahujan Samaj Party has emerged in UP. But even there, it took more than half a century for Kanshi Ram—and then Mayawati—to succeed. Kanshi Ram worked for years, painstakingly making alliances with other subordinated castes, to achieve this victory. The BSP needed the peculiar demography of Uttar Pradesh and the support of many OBCs. But if it is to grow as a political party, it will have to make alliances that will dilute its political thrust. For a Dalit candidate to win an election from an open seat—even in UP—continues to be almost impossible. Still, notwithstanding the charges of corruption and malpractice, I don’t think anybody should ever minimise the immense contribution the BSP has made in building Dalit dignity. The real worry is that even as Dalits are becoming more influential in parliamentary politics, democracy itself is being undermined in serious and structural ways.

Your account of the manner in which Gandhi prevailed over Ambedkar on the issue of the Communal Award, in which the British awarded a separate electorate for untouchables, is fascinating—the description of how Ambedkar had to give up his dream and sign the Poona Pact in 1932. But I have a question about the issue of separate electorates. Many historians argue that this idea really was at the root of the problems that would lead to Partition. And many would argue against separate electorates. Do you think that India still needs separate electorates?

I think our first-past-the-post electoral system is gravely flawed and is failing us. We need to rethink it. But I think we should be careful of collapsing all these very contentious issues about separate electorates, the Communal Award and Partition into one big accusatory mess. As I said earlier, Ambedkar had thought out the demand for a separate electorate and separate representation for untouchables very carefully. I really don’t want to restate what I’ve written...but let’s just say that he had come up with a brilliant and unique plan.

His idea really was to create a situation in which Dalits could develop into a political community with its own leaders. His proposal for a separate electorate was to last for only 10 years. And we are talking here about a people who were ostracised by the privileged castes for thousands of years in the most unimaginably crude and cruel manner—people who were shunned, who were not allowed access to public wells, to education, to temples, besides other things. People who were not entitled to anything except violence and abuse. But when they asked for a separate electorate, everybody behaved as though the world was ending.

Gandhi went on an indefinite hunger strike and public pressure forced Ambedkar to give up his demand and sign the Poona Pact. It was preposterous. How can we possibly say that Ambedkar’s demand for a separate electorate led to Partition? The impulse was exactly the opposite. He was trying to bring liberty and equality to a society that practised a vicious form of apartheid. He was talking about justice, brotherhood, unity and fellow feeling—not Partition. But caste hierarchy means that only the privileged can close the door on Dalits.

When Dalits close the door on themselves, it is made out to be an act of treachery. Also, while we like to place all the blame for Partition on Jinnah—using the word ‘blame’ presupposes that everybody agrees that Partition was a terrible thing, but even that is not true—we forget that people like Bhai Parmanand, a founder-member of the Ghadar Party, a pillar of the Arya Samaj in Lahore, and later an important leader of the Hindu Mahasabha, suggested, as far back as 1905, during the partition of Bengal, that Sindh should be joined with Afghanistan and the North West Frontier Province, and should be united into a great Muslim Kingdom. Partition happened because a whole set of forces was set into play, and it all spun out of the control of the men who had positioned themselves at the helm of affairs.

You criticise Ambedkar quite harshly for his views on Adivasis.

Ambedkar speaks about Adivasis in the same patronising way that Gandhi speaks about untouchables. It’s hard to understand how a man who saw the insult to his own people so clearly could have done that.

Ambedkar was a man of reason, and a man with a keen sense of justice. I believe he would have taken the criticism seriously and would have changed his views. But that’s not the only criticism I have of him. In his embrace of Western liberalism, his support of urbanisation and modern ‘development’, he failed to see the seeds of catastrophe that were embedded in it. I have written about this at some length too.

You have also explored the great failure of Communists to address caste. You write that “they treated caste as a sort of folk dialect derived from the classical language of class analysis”. I think all Communists should read your precise take on the great trade union leader S.A. Dange. My question to you is this: Party communism has disappointed you. But is there any version of Communism that you support and endorse?

My criticism of the way mainstream Communist parties have dealt with caste goes all the way back to The God of Small Things. When the novel came out in 1997, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) was extremely angry with the book. They were angry with my depiction of a character called Comrade K.N.M. Pillai who was a member of the Communist Party and his prejudices against Velutha, a Dalit who was one of the main characters in the book. Communists and Dalits ought to have been natural allies, but sadly that has just not happened. The rift began in the late 1920s, quite soon after the Communist Party of India was formed. S.A. Dange—a Brahmin like many Communist leaders tend to be even today, and one of its chief ideologues—organised India’s first Communist trade union, the Girni Kamgar Union with 70,000 members. A large section of the workers were Mahars, untouchables, the caste that Ambedkar belonged to. They were only employed in the lower-paid jobs in the spinning department, because in the weaving department, workers had to hold the thread in their mouths, and the untouchables’ saliva was considered polluting to the product. In 1928, Dange led the Girni Kamgar Union’s first major strike. Ambedkar suggested that one of the issues that ought to be raised was equality and equal entitlement within the ranks of workers. Dange did not agree, and this led to a bitter falling out. That was when Ambedkar said, “Caste is not just a division of labour, it is a division of labourers.” There is a very very compelling section in Annihilation of Caste in which Ambedkar writes about Caste and Socialism. Is there a version of Communism that I support and endorse? I’m not sure what that means. I am not a Communist. But I do think that we are in dire need of a structural and robust criticism of capitalism, and I do not mean just crony capitalism.

Right now, the new player on the political scene, the Aam Aadmi Party, which is obviously inspired by Gandhian symbolism, is taking on crony capitalism. It has attacked Mukesh Ambani and RIL, who you wrote about in your last big essay Capitalism: A Ghost Story. What are your views on AAP?

It’s a little difficult to have a coherent view on AAP because it doesn’t seem to have a coherent view of itself. I am not an admirer of anti-corruption as a political ideology, because I think corruption is the manifestation of a problem, and not the problem itself. Of course, it gets a lot of political traction in an election year—after all even the corrupt are against corruption—but eventually it will lead us down a blind alley. But I was one of the people who cheered when AAP took on Mukesh Ambani. Suddenly everybody, the mainstream media as well as the social media, began to discuss the Ambanis and the gas-pricing issue—these are things that hardly anybody dared to even whisper about only a few months ago. We all remember how the news of the Ambani car crash in Mumbai was just blanked out. On this score, the Aam Aadmi Party has put a little steel into everybody’s spine. They identify themselves with the Gandhi cap, but going after industrial houses in this way is very un-Gandhian activity, and I’m all for it. I just hope it doesn’t end in a gladiatorial inter-corporate war, where a new monster takes the place of the old one. Mud-slinging and allegations about who has been bought over or bribed by whom is good entertainment, but the rot is deeper than corruption and bribery. The real problem as I see it is that the big corporations—Tata, Reliance, Jindals, Vedanta and several others—run so many businesses simultaneously. Mukesh Ambani is personally worth something like 1,000 billion rupees. But the Tatas, Vedanta, Jindals, Adanis are not all that different. Even if everything is completely above board there is a problem. Even if you are a hard-core classical capitalist you have to see there is a problem here. This kind of cross-ownership of businesses, this scale of profits—limitless profits—accruing to fewer and fewer people, the conflict of interest between corporates and the media—how can you have a free press that is owned and run by corporations? I understand that as a political strategy, AAP is singling out Mukesh Ambani and taking him on for the sheer spectacle of it. Having a 27-storeyed tower built as a personal residence—it’s hubris, he was asking, begging, to be taken down. But at some point I would be glad to see the problem being addressed in a more serious and structural way. Particularly since we are looking to AAP to put a few roadblocks in the way of what is being called the rise of Moditva—which is basically corporate capitalism fused with primitive fascism.

Many people will take issue with your interpretation when you say “there was never much daylight between Gandhi’s views on caste and those of the Hindu Right. From a Dalit point of view Gandhi’s assassination could appear to be more a fratricidal killing than an assassination by an ideological opponent”. You then go on to say that Narendra Modi is able to invoke Gandhi without the slightest discomfort because of this. Are you therefore handing Gandhi over to the Hindu Right? He is someone they have been eager to appropriate, so are you not playing into their hands?

Gandhi’s not a stuffed toy, and who am I to hand him over to anyone?

Let me just say this—on the issue of Muslims and their place in the Indian nation there surely were serious ideological differences between Gandhi and the Hindu Right, and for this Gandhi paid with his life. But on the issues of caste, religious conversion and cow protection, Gandhi was perfectly in stride with the Hindu Right. At the turn of the century—the 19th and 20th centuries—when various reformist organisations were proselytising to the untouchable population, the right-wing was, if anything, more enthusiastic. For example, V.D. Savarkar, a disciple of Tilak’s, and a hero of the Hindu Right, supported the 1927 Mahad satyagraha which Ambedkar led, for the untouchables’ right to use water from a public tank. Gandhi’s support was less forthcoming. Who were the signatories to the Poona Pact?

There were many, but among them were G.D. Birla, Gandhi’s industrialist-patron, who bankrolled him for most of his life; Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya, a conservative Brahmin and founder of the Hindu Mahasabha; and Savarkar, who was accused of being an accomplice in the assassination of Gandhi. They were all interconnected in complex ways.

Birla funded Gandhi as well as the Arya Samaj’s Shuddhi movement. When the RSS was banned after the assassination of Gandhi, Birla lobbied for the ban to be lifted. A recent report in Caravan about Swami Aseemanand, a major RSS leader and the son of a devout Gandhian, who is in jail, being tried for orchestrating a series of bomb blasts including the Samjhauta Express blast, in which about 80 people were killed, describes how boys in his ashram in Gujarat were made to chant the Ekata mantra every morning, an ode to national unity that invokes Gandhi as well as M.S. Golwalkar, the most important RSS ideologue.

Narendra Modi delivers many of his hissy pronouncements from a spanking new convention hall in Gujarat called Mahatma Mandir. In 1936, Gandhi wrote an extraordinary essay calledThe Ideal Bhangi which he ends by saying—“Such an ideal Bhangi, while deriving his livelihood from his occupation, would approach it only as a sacred duty. In other words, he would not dream of amassing wealth out of it.” Seventy years later, in his book, Karmayogi (which he withdrew after the Balmiki community protested), Narendra Modi said: “I do not believe they have been doing this job just to sustain their livelihood. Had this been so, they would not have continued with this kind of job generation after generation.... At some point of time somebody must have got the enlightenment that it is their (Balmikis’) duty to work for the happiness of the entire society and the Gods; that they have to do this job bestowed upon them by Gods; and this job should continue as internal spiritual activity for centuries.” You tell me—where’s the daylight?

When Arundhati Roy does a scathing critique of a man as revered as Mahatma Gandhi, it gets noticed around the world. Some would argue that keeping a beautiful idea alive is more important than undermining it with a certain reality.

That’s a good question. I actually thought about that quite a lot—as any writer would, or should. I decided it was completely wrong, completely unacceptable. That kind of a cover-up—and it would be nothing less than a cover-up—comes at a price. And that price is Ambedkar. We have to deal with Gandhi, with all his brilliance and all his flaws, in order to make room for Ambedkar, with all his brilliance as well as his flaws. The Saint must allow the Doctor a place in the light. Ambedkar’s time has come.

In 1936, Dr B.R. Ambedkar was asked to deliver the annual lecture by the Hindu reformist group, the Jat-Pat-Todak Mandal (Forum for Break-up of Caste) in Lahore. When the hosts received the text of the speech, they found the contents “unbearable” and withdrew the invitation. Ambedkar then printed 1,500 copies of his speech at his own expense and it was soon translated into several languages. Annihilation of Caste would go on to have a cult readership among the Dalit community, but remains largely unread by the privileged castes for whom it was written.

Ambedkar’s landmark speech has now been carefully annotated and reprinted. What will certainly draw contemporary public attention to it is the essay written as an introduction by the Booker prize-winning author Arundhati Roy, titled The Doctor and the Saint.

Almost half of the 400-page book is Roy’s essay, the other half Annihilation of Caste. Roy writes about caste in contemporary India before getting into the Gandhi-Ambedkar stand-off. Taking off from what Ambedkar described as “the infection of imitation”, the domino effect of each caste dominating the ones lower down in the hierarchy, Roy says, “The ‘infection of imitation’, like the half-life of a radioactive atom, decays exponentially as it moves down the caste ladder, but never quite disappears. It has created what Ambedkar describes as the system of ‘graded inequality’ in which even the ‘low is privileged as compared with lower. Each class being privileged, every class is interested in maintaining the system’”.

However, the thrust of Roy’s powerful but disturbing essay deals with her exploration of the Gandhi-Ambedkar debate, and the man deified as the father of the nation does not come off well in this book. She writes: “Ambedkar was Gandhi’s most formidable adversary. He challenged him not just politically or intellectually, but also morally. To have excised Ambedkar from Gandhi’s story, which is the story we all grew up on, is a travesty. Equally, to ignore Gandhi while writing about Ambedkar is to do Ambedkar a disservice, because Gandhi loomed over Ambedkar’s world in myriad and un-wonderful ways.”

The Doctor and the Saint, your introduction to this new, annotated edition of Dr Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste, is also a deeply disturbing critique of Gandhi, especially to those of us for whom Gandhi is a loved and revered figure.

Yes, I know. It wasn’t easy to write it either. But in these times, when all of us are groping in the dark, despairing, and unable to understand why things are the way they are, I think revisiting this debate between Gandhi and Ambedkar, however disturbing it may be for some people, however much it disrupts old and settled patterns of thought, will actually, in the end, help illuminate our path. I think Annihilation of Caste is absolutely essential reading. Caste is at the heart of the rot in our society. Quite apart from what it has done to the subordinated castes, it has corroded the moral core of the privileged castes. We need Ambedkar—now, urgently.

Why should Gandhi figure so prominently in a book about Ambedkar? How did that come about?

Ambedkar was Gandhi’s most trenchant critic, not just politically and intellectually, but also morally. And that has just been written out of the mainstream narrative. It’s a travesty. I could not write an introduction to the book without addressing his debate with Gandhi, something which continues to have an immense bearing on us even today.

|

Have you always held these views about Gandhi, or did you discover new aspects to him as you explored him vis-a-vis Ambedkar?

I am not naturally drawn to piety, particularly when it becomes a political manifesto. I mean, for heaven’s sake, Gandhi called eating a “filthy act” and sex a “poison worse than snake-bite”. Of course, he was prescient in his understanding of the toll that the Western idea of modernity and “development” was going to take on the earth and its inhabitants. On the other hand, his Doctrine of Trusteeship, in which he says that the rich should be left in possession of their wealth and be trusted to use it for the welfare of the poor—what we call Corporate Social Responsibility today—cannot possibly be taken seriously. His attitude to women has always made me uncomfortable. But on the subject of caste and Gandhi’s attitude towards it, I was woolly and unclear. Reading Annihilation of Caste prompted me to read Ambedkar’s What Congress and Gandhi Have Done to the Untouchables. I was very disturbed by that. I then began to read Gandhi—his letters, his articles in the papers—tracing his views on caste right from 1909 when he wrote his most famous tract, Hind Swaraj. In the months it took me to research and write The Doctor and the Saint I couldn’t believe some of the things I was reading. Look—Gandhi was a complex figure. We should have the courage to see him for what he really was, a brilliant politician, a fascinating, flawed human being—and those flaws were not to do with just his personal life or his role as a husband and father. If we want to celebrate him, we must have the courage to celebrate him for what he was. Not some imagined, constructed idea we have of him.

You could be accused of selectively picking out quotes from his writing to suit your own imagined, constructed idea of Gandhi....

When a man leaves behind 98 volumes of his Collected Works, what option does anybody have other than to be selective? Of course I have been selective, as selective as everybody else has been. And of course, those choices say a lot about the politics of the person who has done the selecting. My brief was to write an introduction to Annihilation of Caste. Reading Ambedkar made me realise how large Gandhi loomed in Ambedkar’s universe. When I read Gandhi’s pronouncements supporting the caste system, I wondered how his doctrine of non-violence and satyagraha could rest so comfortably on the foundation of a system which can be held in place only by the permanent threat of violence, and the frequent application of unimaginable violence. I grew curious about how Gandhi even came to be called a Mahatma.

I found that the first time he was publicly called Mahatma was in 1915, soon after he returned to India after spending 20 years in South Africa. What had he done in South Africa to earn him that honour?

|

It was consistent, and consistently disturbing. The fact is that whatever else he said and did, and however beautiful some of it was, he did say and write and do some very disturbing things. Those must be explained and accounted for. This applies to all of us, to everybody, sinner and saint alike. Let’s for the sake of argument imagine that someone driven by extreme prejudice ransacks the writings of Rabindranath Tagore. I am not a Tagore scholar, but I very much doubt that he or she would find letters, articles, speeches and interviews that are as worrying as some of the writings in the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi.

You say that Gandhi harboured attitudes that can only be described as racist towards the Blacks during his years in South Africa, you seem to see his positions as flawed and hypocritical. Would you agree with that?

I have not used those adjectives. I think you have inferred them from Gandhi’s speeches and writings reproduced in my introduction, which is perfectly understandable. Actually I don’t think Gandhi was a hypocrite. On the contrary, he was astonishingly frank. And I am impressed that all his writings, some of them—in my view at least—seriously incriminating, have been retained in the Collected Works.

That really is a courageous thing. I have written at length about Gandhi’s years in South Africa. I’ll just say a couple of things here about that period. First, the famous story about Gandhi’s political awakening to racism and imperialism because he was thrown out of a ‘whites only’ compartment in Pietermaritzberg is only half the story. The other half is that Gandhi was not opposed to racial segregation. Many of his campaigns in South Africa were for separate treatment of Indians. He only objected to Indians being treated on a par with ‘raw kaffirs’, which is what he called Black Africans. One of his first political victories was a ‘solution’ to the Durban post office ‘problem’. He successfully campaigned to have a third entrance opened so that Indians would not have to use the same door as the ‘kaffirs’. He worked with the British army in the Anglo-Boer war and during the crushing of the Bambatha rebellion. In his speeches he said he was looking forward to “an Imperial brotherhood”. And so it goes, the story. In 1913, after signing a settlement with the South African military leader Jan Smuts, Gandhi left South Africa. On his way back to India he stopped in London where he was awarded the Kaiser-e-Hind for public service to the British Empire. How did that add up to fighting racism and imperialism?

But ultimately he did fight imperialism, did he not? He led our country to freedom....

What was ‘freedom’ for some was, for others, nothing more than a transfer of power. Once again, I’d say the Gandhi-Ambedkar debate deepens and complicates our understanding of words like “imperialism” and “freedom”. In 1931, when Ambedkar met Gandhi for the first time, Gandhi questioned him about his sharp criticism of the Congress, which at the time amounted to criticising the struggle for the homeland. Ambedkar’s famous, and heart-breaking, reply was: “Gandhiji, I have no homeland. No untouchable worth the name would be proud of this land.”

Even after he returned from South Africa, Gandhi still saw himself as a ‘responsible’ subject of Empire. But in a few years, by the time of the first national non-cooperation movement, Gandhi had turned against the British. Millions of people rallied to his call, and though it would be incorrect to say that he alone led India to freedom from British rule, of course he played a stellar part. Yet in the struggle, though Gandhi spoke about equality and sometimes even sounded like a socialist, he never challenged traditional caste hierarchies or big zamindars.

|

They were irked and limited by British rule and by their own brushes with racism. So they threw their weight behind the national movement.

Around the time Gandhi returned from South Africa, mill workers who had not benefited from the managements’ windfall profits had become restive and there were a series of lightning strikes in the Ahmedabad mills. The mill-owners asked Gandhi to mediate. I have written about Gandhi’s interventions over the years in labour disputes, his handling of labour unions and his advice to workers about strikes—much of it is very puzzling. In other areas too, the famous Gandhian ‘pragmatism’ took some very strange turns. For example, in 1924, when villagers were protesting against the Mulshi Dam being built by the Tatas some distance away from Pune, to generate electricity for the Bombay mills, Gandhi wrote them a letter advising them to give up their protest. His logic is so very similar to the Supreme Court judgement of 2000 that allowed the construction of the World Bank-funded Sardar Sarovar Dam to proceed...so Ambedkar was spot-on when he said, “The question whether the Congress is fighting for freedom has very little importance as compared to the question for whose freedom is the Congress fighting?”

Photograph by Corbis, From Outlook 10 March 2014

In the past you have written powerful political essays based on reporting from the field or on contemporary events as they unfold. But in this work, you seem to have done some very serious historical research and drawn very different conclusions from many known historians who have worked on the national movement, Gandhi and Ambedkar. You are obviously going to be challenged. Do tell us about the journey that writing The Doctor and the Saint involved.

You say I’ll be challenged? Oh, and here I was imagining that it was me that was doing the challenging! Several years ago, S. Anand, the publisher of Navayana, gave me a spiral-bound copy of Annihilation of Caste and asked me if I would write an introduction to it. I read it and found it electrifying. But I was intimidated by the prospect of writing an introduction to it—a real introduction, not just some quotes patched together with praise and banalities. I didn’t feel that I was equipped to do that. I knew it would mean swimming through some pretty treacherous waters. Anand said he would wait, and he did.

|

But coming back to your question of The Doctor and the Saintbeing a challenge—many historians have criticised Gandhi before, for other reasons, so I don’t think I am alone on this one at all. Many Dalits and Dalit scholars have, over the decades, been very sharply critical of Gandhi and Gandhism. Having said that, if this book begins another debate, a real debate, it can only be a good thing. I think it’s high time that there was one. I’m sure there are plenty of people who would be happy to weigh in on it.

Given what happened to Wendy Doniger’s book, are you worried?

Not about this book in particular, no. It’s Ambedkar’s book. But it’s true that we are becoming less and less free to write and say what we think. What the irreverent Mirza Ghalib could say in the 19th century about his relationship with Islam, what Saadat Hasan Manto could say about mullahs in the 1940s, what Ambedkar could say about Hinduism in the 1930s, what Nehru or JP could say about Kashmir—none of us can say today without risking our lives. The argument between Gandhi and Ambedkar that followed the publication of Annihilation of Caste was a harsh, intense debate between two extraordinary men—they were not afraid of real debate. Unlike contemporary bigots who demand book-banning, Gandhi—who found the text of Ambedkar’s speech disagreeable—actually wanted people to read it. He said, “No reformer can ignore the address.... It has to be read only because it is open to serious objection. Dr Ambedkar is a challenge to Hinduism.”

Your introduction begins with a powerful critique of the all-pervasive domination of traditional upper castes in the establishment, including the media, and you suggest that there has been a ‘project of unseeing’ across the political establishment. Don’t you think that the post-Mandal realities of contemporary India have actually made caste a fundamental unit of all politics?

When you look at India, through the prism of caste, at who controls the money, who owns the corporations, who owns the big media, who makes up the judiciary, the bureaucracy, who owns land, who doesn’t—contemporary India suddenly begins to look extremely un-contemporary. Caste was the engine that drove Indian society—not just Hindu society—much before the recommendations of the Mandal Commission. A long section of The Doctor and the Saint is an analysis of how, in the late 19th century, when the idea of ‘empire’ began to mutate into the idea of a ‘nation’, when the new ideas of governance and ‘representation’ arrived on our shores, it led to an immense anxiety about demography, about numbers. For centuries before that, millions of people who belonged to the subordinated castes—those who had been socially ostracised by privileged castes for thousands of years—had been converting to Islam, and later to Sikhism and Christianity to escape the stigma of their caste. But suddenly numbers began to matter. The almost fifty million “untouchables” became crucial in the numbers game. A raft of Hindu reformist outfits began to proselytise among them, to prevent conversion. The Arya Samaj started the Shuddhi movement—to ‘purify the impure’—to try and woo untouchables and Adivasis back into the ‘Hindu fold’. A version of that is still going on today with the VHP and the Bajrang Dal running their ‘Ghar Vapasi’ programmes in which Adivasi people are ‘purified’ and ‘returned’ to Hinduism. So yes, caste was, and continues to be, the fundamental unit of all politics in India.

So how can you call it a ‘project of unseeing’?

The ‘project of unseeing’ that I write about is something else altogether. It’s about the ways in which influential Indian intellectuals today, particularly those on the Left, for whom caste is just a footnote—an awkward, inconvenient appendage of reductive Marxist class analysis—have rendered caste invisible. To say “we don’t believe in caste” sounds nice and progressive. But it is either an act of evasion, or it comes from a position of such rarefied privilege where caste is not encountered at all. The ‘project of unseeing’ exists in almost all of our cultural practice—does Bollywood deal with it? Never. How many of our high-profile writers deal with it? Very few. Those who write about justice and identity, about the ill effects of neo-liberalism—how many address the issue of caste? Even some of our most militant people’s movements elide caste.

|

You say that caste in India—“one of the most brutal modes of hierarchical social organisation that human society has known—has managed to escape censure because it is so fused with Hinduism, and by extension with so much that is seen to be kind and good—mysticism, spiritualism, non-violence, tolerance, vegetarianism, Gandhi, yoga, backpackers, the Beatles—that, at least to outsiders, it seems impossible to pry it loose and try to understand it”. You argue that caste prejudice is on a par with racial discrimination and apartheid but has not been treated as such. Many would argue that electoral politics and reservation are adequate to deal with historical injustice. But recently a senior Congress leader, Janardhan Dwivedi, said reservation should be discontinued. How would you respond to such an argument?

It was an outrageous thing for anyone to say. Reservation is extremely important, and I have written at some length about it. To be eligible for the reservation policy, a Scheduled Caste person needs to have completed high school. Government figures say more than 70 per cent of Scheduled Caste students drop out before they matriculate. Which means for even low-end government jobs only one in every four Dalits is eligible. For a white-collar job, the minimum qualification is a graduate degree. Just over 2 per cent of Dalits are graduates. Even though it actually applies to so few, the reservation policy has meant that Dalits at least have some representation in the echelons of power. This is absolutely vital. Look at what one Ambedkar, who had the good fortune to get a scholarship to study in Columbia, managed to do. It is thanks to reservation that Dalits are now lawyers, doctors, scholars and civil servants. But even this little window of opportunity is resented and is under fire from the privileged. And the track record of government institutions, the judiciary, the bureaucracy and even supposedly progressive institutions like jnu in implementing reservation is appalling. There is only one government department in which Dalits are over-represented by a factor of six.

Almost 90 per cent of those designated as municipal sweepers—people who clean streets, who risk their lives to go down manholes and service the sewage system, who clean toilets and do menial jobs—are Dalits. Even this sector is up for privatisation now, which means private companies will be able to subcontract jobs on a temporary basis to Dalits for less pay and with no guarantee of job security. Of course there are problems with people getting fake certificates and so on. Those need to be addressed. But to use that to say reservation shouldn’t exist is ridiculous.

But surely you agree that the rise of Dalit parties like the BSP marks something close to a revolution in Indian democracy?

The rise of Dalit political parties has been a dazzling phenomenon.

But then our electoral politics, in the present shape, cannot really be revolutionary, can it? The book, and not just the introduction, deals with it in some detail. Ambedkar’s confrontation with Gandhi at the Second Round Table Conference in London in 1931 had precisely to do with that—with their very different views on the matter of political representation of and for Dalits.

Ambedkar believed that the right to representation was a basic right.

|

Gandhi played a great part in seeing to it that Ambedkar’s project of developing untouchables into a political community that was aware of its rights, that could choose its own representatives from among themselves, was thwarted and undermined. Even today Dalits are paying the price for that. Despite these odds, the Bahujan Samaj Party has emerged in UP. But even there, it took more than half a century for Kanshi Ram—and then Mayawati—to succeed. Kanshi Ram worked for years, painstakingly making alliances with other subordinated castes, to achieve this victory. The BSP needed the peculiar demography of Uttar Pradesh and the support of many OBCs. But if it is to grow as a political party, it will have to make alliances that will dilute its political thrust. For a Dalit candidate to win an election from an open seat—even in UP—continues to be almost impossible. Still, notwithstanding the charges of corruption and malpractice, I don’t think anybody should ever minimise the immense contribution the BSP has made in building Dalit dignity. The real worry is that even as Dalits are becoming more influential in parliamentary politics, democracy itself is being undermined in serious and structural ways.

Your account of the manner in which Gandhi prevailed over Ambedkar on the issue of the Communal Award, in which the British awarded a separate electorate for untouchables, is fascinating—the description of how Ambedkar had to give up his dream and sign the Poona Pact in 1932. But I have a question about the issue of separate electorates. Many historians argue that this idea really was at the root of the problems that would lead to Partition. And many would argue against separate electorates. Do you think that India still needs separate electorates?

I think our first-past-the-post electoral system is gravely flawed and is failing us. We need to rethink it. But I think we should be careful of collapsing all these very contentious issues about separate electorates, the Communal Award and Partition into one big accusatory mess. As I said earlier, Ambedkar had thought out the demand for a separate electorate and separate representation for untouchables very carefully. I really don’t want to restate what I’ve written...but let’s just say that he had come up with a brilliant and unique plan.

His idea really was to create a situation in which Dalits could develop into a political community with its own leaders. His proposal for a separate electorate was to last for only 10 years. And we are talking here about a people who were ostracised by the privileged castes for thousands of years in the most unimaginably crude and cruel manner—people who were shunned, who were not allowed access to public wells, to education, to temples, besides other things. People who were not entitled to anything except violence and abuse. But when they asked for a separate electorate, everybody behaved as though the world was ending.

|