'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label crony. Show all posts

Showing posts with label crony. Show all posts

Thursday, 27 June 2024

Wednesday, 24 April 2024

Wednesday, 20 September 2023

Sunday, 6 August 2023

Tuesday, 14 March 2023

Are these rumbles of discontent coming together?

Jawed Naqvi in The Dawn

A PEOPLE’S movement is underway in Israel against its ultra right-wing government. Prime Minister Netanyahu is trying to subvert the judiciary’s neutrality, with a selfish aim to kill the criminal cases hanging over his head and that of his colleagues. In quite a few democracies, the judiciary is or has been under assault from the right wing for similar reasons. India is witnessing it in unsubtle ways. Pakistan too has seen political interference with the judiciary at least since the hanging of Bhutto. Then Nawaz Sharif and Gen Musharraf, vicious to each other, took turns to undermine the courts. Pakistan, however, has seen mass movements too that have thrown out military dictators and restored democracy even if intermittently. Where’s that old fire in the belly for India?

Describing the unprecedented attack on India’s democracy starkly at a Cambridge University talk is one thing. Few Indian politicians are capable of speaking with conviction without a teleprompter as Rahul Gandhi recently did before an enlightened audience, while also making plenty of sense. But just as he was holding forth — at a talk called ‘Learning to listen in the 21st century’ — two unrelated landmark events were unfolding in Turkiye and Israel. Was he listening to them too?

The events might send any struggling democratic opposition to the drawing board. In Turkiye, a last-minute collapse of the alliance of six disparate parties, preparing to challenge President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s re-election in May, holds a lesson for any less-than-solid political alliance about possible ambush on the eve of an assured victory. Equally instructive was the opposition’s ability to bury its differences promptly, something that eludes India. The Turkish groups have made compromises with each other so that their common goal to defeat Erdogan remains paramount. There are good chances they would succeed, but even if they don’t, it won’t be for want of giving their best to restore Turkiye’s secular democracy.

However, it was the coming out of Israel’s air force pilots to join the swarming protests against the Netanyahu government that is truly remarkable, and unprecedented. These pilots are usually adept at bombing vulnerable neighbourhoods, including Palestinian quarters. But their taking a stand in defence of democracy offers a lesson to every country with a strong military. There were rumblings in India once. Jaya Prakash Narayan, the mass leader opposed Indira Gandhi’s authoritarian patch and called for the army and the police to disobey her, an unusual quest but an utterly democratic call when democracy itself is being murdered. The RSS had supported the JP movement. The boot today is on the other foot. Does the Indian opposition have the conviction to follow in JP’s footsteps to take on Prime Minister Narendra Modi? Does it at all feel the dire need to make sacrifices and compromises to rescue and heal the wounded nation?

The Israeli government may or may not succeed in neutralising the supreme court, which it has set out to do. But the masses are out on the streets to act when their nation is in peril. And India cannot exist as a nation without democracy. Secular democracy enshrined in its constitution binds it into a whole.

Rahul Gandhi has evolved as a contender for any challenging job that could help save the Indian republic from its approaching destruction. But he should also have a chat with Prof Amartya Sen perhaps who was quoted recently as saying that Mamata Bannerjee would make a good prime minister. Others have their hats in the ring. Gandhi’s talk in the hallowed portals of Cambridge bonded nicely with his 4,000-kilometre walk recently, from the southern tip of India to what is effectively the garrison area of Jammu and Kashmir. No harm if the walk served as a learning curve for the Gandhi scion, but even better if it were a precursor for a mass upsurge as is happening elsewhere, and which has seen successful outcomes in many Latin American and African states.

Rahul Gandhi spoke about the surveillance, which opposition politicians and journalists among others have been illegally put under. His points about deep-seated corruption, that shows up graphically as crony capitalism, are all well taken. Few can match the feat of mass contact across the country that he displayed recently and his declamation at the world’s premier university. The point is that Cambridge University cannot change the oppressive government in India. Only the Indian opposition can. Rahul Gandhi has the credentials to weld mutually suspicious opposition parties into a force to usher in the needed change.

There’s no dearth of issues to unite the people and the parties. To cite one, call out the BJP-backed ruling alliances in north-eastern states where its supporters assert their right to eat beef. And place it along the two Muslim boys incinerated in a jeep near Delhi by alleged cow vigilantes. The criminality and the hypocrisy of it.

The fascist assault on India’s judiciary is an issue waiting to be taken up for nationwide mobilisation. The assault comes at a time when the new chief justice is one with a mind of his own. Judges have stopped accepting official briefs in sealed envelopes as had become the practice, dodging public scrutiny, say, in the controversial warplanes deal with France. The court has set up a probe into the Adani affair, something unthinkable until recently.

The timing of the vicious criticism of the judiciary is noteworthy. The law minister described the judges as unelected individuals, perhaps implying they were answerable to the elected parliament like any other bureaucrat. This is mischievous. The supreme court set new transparent principles in the appointment of election commissioners. It’s a rap on the knuckles of an unholy system. Could anyone call it a fair election in a secular democracy when people are nefariously polarised and the election commission looks the other way? The questions are best answered by opposition parties, preferably in unison.

A PEOPLE’S movement is underway in Israel against its ultra right-wing government. Prime Minister Netanyahu is trying to subvert the judiciary’s neutrality, with a selfish aim to kill the criminal cases hanging over his head and that of his colleagues. In quite a few democracies, the judiciary is or has been under assault from the right wing for similar reasons. India is witnessing it in unsubtle ways. Pakistan too has seen political interference with the judiciary at least since the hanging of Bhutto. Then Nawaz Sharif and Gen Musharraf, vicious to each other, took turns to undermine the courts. Pakistan, however, has seen mass movements too that have thrown out military dictators and restored democracy even if intermittently. Where’s that old fire in the belly for India?

Describing the unprecedented attack on India’s democracy starkly at a Cambridge University talk is one thing. Few Indian politicians are capable of speaking with conviction without a teleprompter as Rahul Gandhi recently did before an enlightened audience, while also making plenty of sense. But just as he was holding forth — at a talk called ‘Learning to listen in the 21st century’ — two unrelated landmark events were unfolding in Turkiye and Israel. Was he listening to them too?

The events might send any struggling democratic opposition to the drawing board. In Turkiye, a last-minute collapse of the alliance of six disparate parties, preparing to challenge President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s re-election in May, holds a lesson for any less-than-solid political alliance about possible ambush on the eve of an assured victory. Equally instructive was the opposition’s ability to bury its differences promptly, something that eludes India. The Turkish groups have made compromises with each other so that their common goal to defeat Erdogan remains paramount. There are good chances they would succeed, but even if they don’t, it won’t be for want of giving their best to restore Turkiye’s secular democracy.

However, it was the coming out of Israel’s air force pilots to join the swarming protests against the Netanyahu government that is truly remarkable, and unprecedented. These pilots are usually adept at bombing vulnerable neighbourhoods, including Palestinian quarters. But their taking a stand in defence of democracy offers a lesson to every country with a strong military. There were rumblings in India once. Jaya Prakash Narayan, the mass leader opposed Indira Gandhi’s authoritarian patch and called for the army and the police to disobey her, an unusual quest but an utterly democratic call when democracy itself is being murdered. The RSS had supported the JP movement. The boot today is on the other foot. Does the Indian opposition have the conviction to follow in JP’s footsteps to take on Prime Minister Narendra Modi? Does it at all feel the dire need to make sacrifices and compromises to rescue and heal the wounded nation?

The Israeli government may or may not succeed in neutralising the supreme court, which it has set out to do. But the masses are out on the streets to act when their nation is in peril. And India cannot exist as a nation without democracy. Secular democracy enshrined in its constitution binds it into a whole.

Rahul Gandhi has evolved as a contender for any challenging job that could help save the Indian republic from its approaching destruction. But he should also have a chat with Prof Amartya Sen perhaps who was quoted recently as saying that Mamata Bannerjee would make a good prime minister. Others have their hats in the ring. Gandhi’s talk in the hallowed portals of Cambridge bonded nicely with his 4,000-kilometre walk recently, from the southern tip of India to what is effectively the garrison area of Jammu and Kashmir. No harm if the walk served as a learning curve for the Gandhi scion, but even better if it were a precursor for a mass upsurge as is happening elsewhere, and which has seen successful outcomes in many Latin American and African states.

Rahul Gandhi spoke about the surveillance, which opposition politicians and journalists among others have been illegally put under. His points about deep-seated corruption, that shows up graphically as crony capitalism, are all well taken. Few can match the feat of mass contact across the country that he displayed recently and his declamation at the world’s premier university. The point is that Cambridge University cannot change the oppressive government in India. Only the Indian opposition can. Rahul Gandhi has the credentials to weld mutually suspicious opposition parties into a force to usher in the needed change.

There’s no dearth of issues to unite the people and the parties. To cite one, call out the BJP-backed ruling alliances in north-eastern states where its supporters assert their right to eat beef. And place it along the two Muslim boys incinerated in a jeep near Delhi by alleged cow vigilantes. The criminality and the hypocrisy of it.

The fascist assault on India’s judiciary is an issue waiting to be taken up for nationwide mobilisation. The assault comes at a time when the new chief justice is one with a mind of his own. Judges have stopped accepting official briefs in sealed envelopes as had become the practice, dodging public scrutiny, say, in the controversial warplanes deal with France. The court has set up a probe into the Adani affair, something unthinkable until recently.

The timing of the vicious criticism of the judiciary is noteworthy. The law minister described the judges as unelected individuals, perhaps implying they were answerable to the elected parliament like any other bureaucrat. This is mischievous. The supreme court set new transparent principles in the appointment of election commissioners. It’s a rap on the knuckles of an unholy system. Could anyone call it a fair election in a secular democracy when people are nefariously polarised and the election commission looks the other way? The questions are best answered by opposition parties, preferably in unison.

Wednesday, 1 February 2023

Friday, 26 August 2022

Friday, 12 August 2022

Tuesday, 23 February 2021

Bleeding from Shylock’s cut

Jawed Naqvi in The Dawn

SHYLOCK is the big business, Antonio, the political parties. Let’s throw in Portia, symbolising law and justice, but which mostly eludes Indians currently. The news is heart-warming in the interregnum though. A brilliant woman journalist won a tenacious legal battle with an alleged sex predator of a powerful social echelon. And octogenarian leftist poet Varavara Rao got bail too, albeit for six months.

But Rao’s comrades, India’s most brilliant and selfless souls, are cramming the jails. A battery of leftist intellectuals and lawyers along with a merrily self-effacing octogenarian Jesuit priest stand accused of plotting to murder the prime minister in a laughably bizarre plot. Others are facing sedition charges for orchestrating communal violence in Delhi, which their rivals actually waged under police protection.

An American newspaper has revealed how the dubious assassination plot was structured around hacked computers that were used to plant the “evidence” of the purported crime. So, the victories here and there are welcome aberrations — happy aberrations — in a system that stands entrenched against equal rights and dignity for women and which ambushes dissenting citizens at will.

It’s no secret that major political parties receive funds from big business, which becomes a fertile ground for quid pro quo. In fact, it’s a curious rule of thumb that the parties whose leaders are in jail or face charges for alleged graft, are precisely the ones that the corporate lobbies shunned, and, therefore, did not favour with their largesse. It is also likely that the leaders didn’t accept the implied quid pro quo and chose to suffer.

It’s a bit like the movie industry. If one didn’t pick the money from the usurious market the movie is likely never going to find a theatre to screen it. Mayawati and Lalu Yadav are a case in point of politicians who have been made an example of for seeking alternative routes of raising money, tainted money, to fight costly elections, and which they mostly won. Portia will have to be more innovative than leaning on her fabled court craft and throwing in a clever interpretation of law to tilt the argument. Today, she has to weigh the cases as presented.

Chara ghotala or fodder scam is up for public scrutiny and trial by media, a bail-less crime, but an opaque defence deal has to be decided for reasons of national security through sealed envelopes in highest court rooms. This, therefore, is a political battle and has to be fought politically. It is far-fetched to think of defeating a closet patriarchy or a renegade state in a court battle.

In this regard, a key component of Prime Minister Modi’s hare-brained demonetisation move had a clever edge. He mopped up 85 per cent of India’s cash on Nov 8, 2016. The Uttar Pradesh assembly polls began on Feb 11, 2017. By cancelling big currency notes on the eve of a huge election, which Uttar Pradesh always is, he sucked out a vital resource the rivals needed to give him a good fight.

Why don’t Indian parties crowd-fund as some, but only some, sections of the left do? Even in the heartland of capitalism in the United States, Bernie Sanders could come tantalisingly close to becoming president with crowd funding. Delhi’s Aam Aadmi Party came to power with the help of this mostly shunned method of raising electoral funds. In the bargain, AAP inspired donors to see themselves as stakeholders in the great endeavour.

We read in the morning paper that India’s main opposition Congress party has run out of money. Elections are due in key states where the party could do well, primarily Assam, with clever handling. It’s a wrong time not to have money. West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Pondicherry and Kerala are also up for polls.

Being in penury, or near penury, is, however, a good sign for the Congress party and may not be such a bad idea for India’s democracy either. Remember the tycoons muscling their way through pliable media contacts to claim cabinet berths for their acolytes in the second innings of the Congress-led alliance of Manmohan Singh? The ministry of telecommunications was crucial to the quest. And with all the deals being done to monopolise data and e-commerce today, the stakes were bound to be high. The BJP has emerged as the monopoly beneficiary of corporate donations, not least by tweaking the law to make the transactions opaque. No surprise there.

A great reason for the Congress’s financial crunch is Rahul Gandhi’s decision to make a direct connection between India’s prevailing economic crisis and Mr Modi’s patronage of his crony capitalist friends. Protesting farmers, dissenting intellectuals and assorted environmentalists across the world have seen through the plot. (Whoever can see the plot is an enemy of the state.)

On the flip side of the Congress’s course correction under Gandhi, an interview was published of Punjab’s Congress Chief Minister Amarinder Singh. He is rowing back from the bold demands by the farmers for the repeal of pro-business farm laws. Singh favours suspending the laws for two years instead of annulling them. The India Today magazine did some fact-checking to show that Singh had not met Modi’s friend Mukesh Ambani, as claimed, a day ahead of the nationwide strike by the farmers. The cordial picture of the two was from 2017.

Amarinder’s challenger in Congress is cricketer-turned-politician Navjot Sidhu, a vocal critic of big business. Shylock is hemorrhaging India. Rahul Gandhi is losing his MLAs to corporate-political pelf, the latest casualty being his government in Pondicherry. It’s time he went to the people with the bowl, an agreeable way to involve them in his bold analysis of the country’s crisis. He can start to stitch the wounds, not as a grand leader for which he must win a mandate, but as a caring citizen like those languishing in jails. The Congress will be the richer for it. Good for Portia too.

SHYLOCK is the big business, Antonio, the political parties. Let’s throw in Portia, symbolising law and justice, but which mostly eludes Indians currently. The news is heart-warming in the interregnum though. A brilliant woman journalist won a tenacious legal battle with an alleged sex predator of a powerful social echelon. And octogenarian leftist poet Varavara Rao got bail too, albeit for six months.

But Rao’s comrades, India’s most brilliant and selfless souls, are cramming the jails. A battery of leftist intellectuals and lawyers along with a merrily self-effacing octogenarian Jesuit priest stand accused of plotting to murder the prime minister in a laughably bizarre plot. Others are facing sedition charges for orchestrating communal violence in Delhi, which their rivals actually waged under police protection.

An American newspaper has revealed how the dubious assassination plot was structured around hacked computers that were used to plant the “evidence” of the purported crime. So, the victories here and there are welcome aberrations — happy aberrations — in a system that stands entrenched against equal rights and dignity for women and which ambushes dissenting citizens at will.

It’s no secret that major political parties receive funds from big business, which becomes a fertile ground for quid pro quo. In fact, it’s a curious rule of thumb that the parties whose leaders are in jail or face charges for alleged graft, are precisely the ones that the corporate lobbies shunned, and, therefore, did not favour with their largesse. It is also likely that the leaders didn’t accept the implied quid pro quo and chose to suffer.

It’s a bit like the movie industry. If one didn’t pick the money from the usurious market the movie is likely never going to find a theatre to screen it. Mayawati and Lalu Yadav are a case in point of politicians who have been made an example of for seeking alternative routes of raising money, tainted money, to fight costly elections, and which they mostly won. Portia will have to be more innovative than leaning on her fabled court craft and throwing in a clever interpretation of law to tilt the argument. Today, she has to weigh the cases as presented.

Chara ghotala or fodder scam is up for public scrutiny and trial by media, a bail-less crime, but an opaque defence deal has to be decided for reasons of national security through sealed envelopes in highest court rooms. This, therefore, is a political battle and has to be fought politically. It is far-fetched to think of defeating a closet patriarchy or a renegade state in a court battle.

In this regard, a key component of Prime Minister Modi’s hare-brained demonetisation move had a clever edge. He mopped up 85 per cent of India’s cash on Nov 8, 2016. The Uttar Pradesh assembly polls began on Feb 11, 2017. By cancelling big currency notes on the eve of a huge election, which Uttar Pradesh always is, he sucked out a vital resource the rivals needed to give him a good fight.

Why don’t Indian parties crowd-fund as some, but only some, sections of the left do? Even in the heartland of capitalism in the United States, Bernie Sanders could come tantalisingly close to becoming president with crowd funding. Delhi’s Aam Aadmi Party came to power with the help of this mostly shunned method of raising electoral funds. In the bargain, AAP inspired donors to see themselves as stakeholders in the great endeavour.

We read in the morning paper that India’s main opposition Congress party has run out of money. Elections are due in key states where the party could do well, primarily Assam, with clever handling. It’s a wrong time not to have money. West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Pondicherry and Kerala are also up for polls.

Being in penury, or near penury, is, however, a good sign for the Congress party and may not be such a bad idea for India’s democracy either. Remember the tycoons muscling their way through pliable media contacts to claim cabinet berths for their acolytes in the second innings of the Congress-led alliance of Manmohan Singh? The ministry of telecommunications was crucial to the quest. And with all the deals being done to monopolise data and e-commerce today, the stakes were bound to be high. The BJP has emerged as the monopoly beneficiary of corporate donations, not least by tweaking the law to make the transactions opaque. No surprise there.

A great reason for the Congress’s financial crunch is Rahul Gandhi’s decision to make a direct connection between India’s prevailing economic crisis and Mr Modi’s patronage of his crony capitalist friends. Protesting farmers, dissenting intellectuals and assorted environmentalists across the world have seen through the plot. (Whoever can see the plot is an enemy of the state.)

On the flip side of the Congress’s course correction under Gandhi, an interview was published of Punjab’s Congress Chief Minister Amarinder Singh. He is rowing back from the bold demands by the farmers for the repeal of pro-business farm laws. Singh favours suspending the laws for two years instead of annulling them. The India Today magazine did some fact-checking to show that Singh had not met Modi’s friend Mukesh Ambani, as claimed, a day ahead of the nationwide strike by the farmers. The cordial picture of the two was from 2017.

Amarinder’s challenger in Congress is cricketer-turned-politician Navjot Sidhu, a vocal critic of big business. Shylock is hemorrhaging India. Rahul Gandhi is losing his MLAs to corporate-political pelf, the latest casualty being his government in Pondicherry. It’s time he went to the people with the bowl, an agreeable way to involve them in his bold analysis of the country’s crisis. He can start to stitch the wounds, not as a grand leader for which he must win a mandate, but as a caring citizen like those languishing in jails. The Congress will be the richer for it. Good for Portia too.

Wednesday, 11 July 2018

The staggering rise of India’s super-rich

India’s new billionaires have accumulated more money, more quickly, than plutocrats in almost any country in history. By James Crabtree in The Guardian

On 3 May, at around 4.45pm, a short, trim Indian man walked quickly down London’s Old Compton Street, his head bowed as if trying not to be seen. From his seat by the window of a nearby noodle bar, Anuvab Pal recognised him instantly. “He is tiny, and his face had been all over every newspaper in India,” Pal recalled. “I knew it was him.”

Few in Britain would have given the passing figure a second look. And that, in a way, was the point. The man pacing through Soho on that Wednesday night was Nirav Modi: Indian jeweller, billionaire and international fugitive.

In February, Modi had fled his home country after an alleged $1.8bn fraud case in which the tycoon was accused of abusing a system that allowed his business to obtain cash advances illegally from one of India’s largest banks. Since then, his whereabouts had been a mystery. Indian newspapers speculated that he might be holed up in Hong Kong or New York. Indian courts issued warrants for his arrest, and the police tried, ineffectually, to track him down.

It was only by chance that Pal spotted him. A standup comic normally based in Mumbai, he happened to be in London for a run of gigs. “My ritual was to go to the same noodle bar, have a meal, and then head to the theatre,” Pal said. “I always sat by the window. And then suddenly Modi walks past. He was unshaven, and had those Apple earphones, the wireless ones. He looked like he was in a hurry.”

It was another month before the press finally caught up with Modi, as reports of his whereabouts emerged in June, along with the suggestion that he was planning to claim political asylum in the UK. (Modi denies wrongdoing, and did not respond to requests for comment.) In the process, Modi also gained entry into one of London’s more notorious fraternities: the small club of Indian billionaires who seem to end up in the British capital following scandals back at home.

The most prominent among these émigré moguls is India’s “King of Good Times”, Vijay Mallya, the one-time aviation magnate and brewer, who transformed Kingfisher beer into a global brand. A few years ago, Mallya was one of India’s most celebrated industrialists, famous for his mullet haircut and flamboyant lifestyle. But in early 2016, Indian authorities filed charges relating to the collapse of his Kingfisher airline, which went bust in spectacular fashion in 2012, leaving behind mountainous debts and irate, unpaid staff. And so, facing allegations of financial irregularities and of refusing to repay outstanding loans, Mallya quietly boarded a plane for Britain, too.

Like Modi, Mallya denies wrongdoing. Last month he released a long statement accusing India’s government of conducting a witch-hunt against him. And to the extent that this claim has some merit, it is because Indian prime minister Narendra Modi (no relation to Nirav Modi) has of late been under great pressure to bring supposedly errant tycoons such as Mallya to book.

Men like Mallya and Modi were members of India’s expanding billionaire class, of whom there are now 119 members, according to Forbes magazine.Last year their collective worth amounted to $440bn – more than in any other country, bar the US and China. By contrast, the average person in India earns barely $1,700 a year. Given its early stage of economic development, India’s new hyper-wealthy elite have accumulated more money, more quickly, than their plutocratic peers in almost any country in history.

On 3 May, at around 4.45pm, a short, trim Indian man walked quickly down London’s Old Compton Street, his head bowed as if trying not to be seen. From his seat by the window of a nearby noodle bar, Anuvab Pal recognised him instantly. “He is tiny, and his face had been all over every newspaper in India,” Pal recalled. “I knew it was him.”

Few in Britain would have given the passing figure a second look. And that, in a way, was the point. The man pacing through Soho on that Wednesday night was Nirav Modi: Indian jeweller, billionaire and international fugitive.

In February, Modi had fled his home country after an alleged $1.8bn fraud case in which the tycoon was accused of abusing a system that allowed his business to obtain cash advances illegally from one of India’s largest banks. Since then, his whereabouts had been a mystery. Indian newspapers speculated that he might be holed up in Hong Kong or New York. Indian courts issued warrants for his arrest, and the police tried, ineffectually, to track him down.

It was only by chance that Pal spotted him. A standup comic normally based in Mumbai, he happened to be in London for a run of gigs. “My ritual was to go to the same noodle bar, have a meal, and then head to the theatre,” Pal said. “I always sat by the window. And then suddenly Modi walks past. He was unshaven, and had those Apple earphones, the wireless ones. He looked like he was in a hurry.”

It was another month before the press finally caught up with Modi, as reports of his whereabouts emerged in June, along with the suggestion that he was planning to claim political asylum in the UK. (Modi denies wrongdoing, and did not respond to requests for comment.) In the process, Modi also gained entry into one of London’s more notorious fraternities: the small club of Indian billionaires who seem to end up in the British capital following scandals back at home.

The most prominent among these émigré moguls is India’s “King of Good Times”, Vijay Mallya, the one-time aviation magnate and brewer, who transformed Kingfisher beer into a global brand. A few years ago, Mallya was one of India’s most celebrated industrialists, famous for his mullet haircut and flamboyant lifestyle. But in early 2016, Indian authorities filed charges relating to the collapse of his Kingfisher airline, which went bust in spectacular fashion in 2012, leaving behind mountainous debts and irate, unpaid staff. And so, facing allegations of financial irregularities and of refusing to repay outstanding loans, Mallya quietly boarded a plane for Britain, too.

Like Modi, Mallya denies wrongdoing. Last month he released a long statement accusing India’s government of conducting a witch-hunt against him. And to the extent that this claim has some merit, it is because Indian prime minister Narendra Modi (no relation to Nirav Modi) has of late been under great pressure to bring supposedly errant tycoons such as Mallya to book.

Men like Mallya and Modi were members of India’s expanding billionaire class, of whom there are now 119 members, according to Forbes magazine.Last year their collective worth amounted to $440bn – more than in any other country, bar the US and China. By contrast, the average person in India earns barely $1,700 a year. Given its early stage of economic development, India’s new hyper-wealthy elite have accumulated more money, more quickly, than their plutocratic peers in almost any country in history.

A cardboard cut-out of billionaire jeweller Nirav Modi at a protest against him in New Delhi in February. Photograph: Chandan Khanna/AFP/Getty Images

Narendra Modi won an overwhelming election victory in 2014, having promised to put a stop to the spate of corruption scandals that had dogged India for much of the previous decade. Many involved prominent industrialists – some directly accused of corruption, while others had simply mismanaged their finances and miraculously managed to escape the consequences. Voters turned to Narendra Modi, the self-described son of a poor tea-seller, hoping he would deliver a new era of clean governance and rapid growth, ridding India of a growing reputation for crony capitalism.

Narendra Modi pledged to end a situation in which the country’s ultra-wealthy – sometimes called “Bollygarchs” – appeared to live by one set of rules, while India’s 1.3 billion people operated by another. Yet as they continue to hide out in cities like London, men like Mallya and Nirav Modi have come to be seen as representing the failure of that pledge; the Indian authorities “have a long road ahead”, as one headline put it in the Hindustan Times last year, referring to a “long and arduous” future extradition process in Mallya’s case.

And as Narendra Modi gears up for a tough re-election battle next year, he is fighting the perception that India is unable to bring such men to heel, and that it has been powerless to respond to the rise of this new moneyed elite and the scandals that have come with them. “This ongoing battle to get India’s big tycoons to play by the rules is one of the biggest challenges we face,” says Reuben Abraham, chief executive of the IDFC Institute, a Mumbai-based thinktank. “Getting it right is central to India’s economic and political future.”

India has long been a stratified society, marked by divisions of caste, race and religion. Prior to the country winning independence in 1947, its people were subjugated by imperial British administrators and myriad maharajas, and the feudal regional monarchies over which they presided. Even afterwards, India remained a grimly poor country, as its socialist leadership fashioned a notably inefficient state-planned economic model, closed off almost entirely from global trade. Over time, India grew more equal, if only in the limited sense that its elite remained poor by the standards of the industrialised west.

But no longer: the last three decades have seen an extraordinary explosion of wealth at the top of Indian society. In the mid-1990s, just two Indians featured in the annual Forbes billionaire list, racking up around $3bn between them. But against a backdrop of the gradual economic re-opening that began in 1991, this has quickly changed. By 2016, India had 84 entries on the Forbes billionaire list. Its economy was then worth around $2.3tn, according to the World Bank. China reached that level of GDP in 2006, but with just 10 billionaires to show for it. At the same stage of development, India had created eight times as many.

In part, this wealth is to be welcomed. This year India will be the world’s fastest-growing major economy. During the last two decades, it has grown more quickly than at any point its history, a record of economic expansion that helped to lift hundreds of millions out of poverty.

Nonetheless, India remains a poor country: in 2016, to be counted among its richest 1% required assets of just $32,892, according to research from Credit Suisse. Meanwhile, the top 10% of earners now take around 55% of all national income – the highest rate for any large country in the world.

Put another way, India has created a model of development in which the proceeds of growth flow unusually quickly to the very top. Yet perhaps because Indian society has long been deeply stratified, this dramatic increase in inequality has not received as much global attention as it deserves. For nearly a century prior to independence, India was governed by the British Raj – a term taken from the Sanskrit rājya, meaning “rule”. For half a century after 1947, a system dominated by pernickety industrial rules emerged, often known as the Licence-Permit-Quota Raj, or Licence Raj for short. Now a system has grown in their place once again: the billionaire Raj.

The rise of India’s super-rich – the first and most obvious manifestation of the billionaire Raj – was propelled by domestic economic reforms. Starting slowly in the 1980s, and then more dramatically against the backdrop of a wrenching financial crisis in 1991, India dismantled the dusty stockade of rules and tariffs that made up the Licence Raj. Companies that had been cosseted under the old regime were cleared out via a mix of deregulation, foreign investment and heightened competition. In sector after sector, from airlines and banks to steel and telecoms, the ranks of India’s tycoons began to swell.

Nothing symbolises the power of this billionaire class more starkly than Antilia, the residential skyscraper built in Mumbai by Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man. Rising 173 metres above India’s financial capital, the steel-and-glass tower is rumoured to have cost more than $1bn to build, looming over a city in which half the population still live in slums.

Narendra Modi won an overwhelming election victory in 2014, having promised to put a stop to the spate of corruption scandals that had dogged India for much of the previous decade. Many involved prominent industrialists – some directly accused of corruption, while others had simply mismanaged their finances and miraculously managed to escape the consequences. Voters turned to Narendra Modi, the self-described son of a poor tea-seller, hoping he would deliver a new era of clean governance and rapid growth, ridding India of a growing reputation for crony capitalism.

Narendra Modi pledged to end a situation in which the country’s ultra-wealthy – sometimes called “Bollygarchs” – appeared to live by one set of rules, while India’s 1.3 billion people operated by another. Yet as they continue to hide out in cities like London, men like Mallya and Nirav Modi have come to be seen as representing the failure of that pledge; the Indian authorities “have a long road ahead”, as one headline put it in the Hindustan Times last year, referring to a “long and arduous” future extradition process in Mallya’s case.

And as Narendra Modi gears up for a tough re-election battle next year, he is fighting the perception that India is unable to bring such men to heel, and that it has been powerless to respond to the rise of this new moneyed elite and the scandals that have come with them. “This ongoing battle to get India’s big tycoons to play by the rules is one of the biggest challenges we face,” says Reuben Abraham, chief executive of the IDFC Institute, a Mumbai-based thinktank. “Getting it right is central to India’s economic and political future.”

India has long been a stratified society, marked by divisions of caste, race and religion. Prior to the country winning independence in 1947, its people were subjugated by imperial British administrators and myriad maharajas, and the feudal regional monarchies over which they presided. Even afterwards, India remained a grimly poor country, as its socialist leadership fashioned a notably inefficient state-planned economic model, closed off almost entirely from global trade. Over time, India grew more equal, if only in the limited sense that its elite remained poor by the standards of the industrialised west.

But no longer: the last three decades have seen an extraordinary explosion of wealth at the top of Indian society. In the mid-1990s, just two Indians featured in the annual Forbes billionaire list, racking up around $3bn between them. But against a backdrop of the gradual economic re-opening that began in 1991, this has quickly changed. By 2016, India had 84 entries on the Forbes billionaire list. Its economy was then worth around $2.3tn, according to the World Bank. China reached that level of GDP in 2006, but with just 10 billionaires to show for it. At the same stage of development, India had created eight times as many.

In part, this wealth is to be welcomed. This year India will be the world’s fastest-growing major economy. During the last two decades, it has grown more quickly than at any point its history, a record of economic expansion that helped to lift hundreds of millions out of poverty.

Nonetheless, India remains a poor country: in 2016, to be counted among its richest 1% required assets of just $32,892, according to research from Credit Suisse. Meanwhile, the top 10% of earners now take around 55% of all national income – the highest rate for any large country in the world.

Put another way, India has created a model of development in which the proceeds of growth flow unusually quickly to the very top. Yet perhaps because Indian society has long been deeply stratified, this dramatic increase in inequality has not received as much global attention as it deserves. For nearly a century prior to independence, India was governed by the British Raj – a term taken from the Sanskrit rājya, meaning “rule”. For half a century after 1947, a system dominated by pernickety industrial rules emerged, often known as the Licence-Permit-Quota Raj, or Licence Raj for short. Now a system has grown in their place once again: the billionaire Raj.

The rise of India’s super-rich – the first and most obvious manifestation of the billionaire Raj – was propelled by domestic economic reforms. Starting slowly in the 1980s, and then more dramatically against the backdrop of a wrenching financial crisis in 1991, India dismantled the dusty stockade of rules and tariffs that made up the Licence Raj. Companies that had been cosseted under the old regime were cleared out via a mix of deregulation, foreign investment and heightened competition. In sector after sector, from airlines and banks to steel and telecoms, the ranks of India’s tycoons began to swell.

Nothing symbolises the power of this billionaire class more starkly than Antilia, the residential skyscraper built in Mumbai by Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man. Rising 173 metres above India’s financial capital, the steel-and-glass tower is rumoured to have cost more than $1bn to build, looming over a city in which half the population still live in slums.

The Antilia building, at right of photograph, in Mumbai. Photograph: Alamy

Advertisement

Ambani owns Reliance Industries, an empire with interests stretching from petrochemicals to telecoms. (His father, Dhirubhai, from whom he inherited his company, was one of the main beneficiaries of the economic reforms of the 1980s.) At Antilia, Ambani entertains guests in a grand, chandeliered ballroom that takes up most of building’s ground floor. There are six storeys of parking for the family’s car collection, while the tower’s higher levels feature opulent apartments and hanging gardens. Further down, in sub-basement 2, the Ambanis keep a recreational floor, which includes an indoor football pitch. Antilia became an instant landmark upon its completion in 2010. The city had long been a place of stark divisions, yet the Ambani’s home almost seemed to magnify this segregation. (A spokesman for Reliance did not respond to a request for comment.)

The emergence of the Indian super-rich was bound up in larger global story. The early 2000s were the heyday of the so-called “great moderation”, when world interest rates stayed low and industrialised nations grew handsomely. This was also when the fortunes of India’s new tycoons began to change. Pumped up by foreign money, domestic bank loans and a surging sense of self-belief, industrialists went on a spending spree. Ambani dumped billions into oil refineries and petrochemical plants. Vijay Mallya spent heavily on new fleets of Airbus jets. Nirav Modi began building a global chain of jewellery stores. Stock markets boomed. From 2004 to 2014, India enjoyed the fastest expansion in its history, averaging growth of more than 8% a year.

The boom years brought benefits, most obviously by reintegrating India into the world economy. Yet this whirlwind growth also proved economically disruptive, socially bruising and environmentally destructive, leaving behind what the writer Rana Dasgupta describes as a sense of national trauma. India’s new wealth has been shared remarkably unevenly, too. Its richest 1% earned about 7% of national income in 1980; that figure rocketed to 22% by 2014, according to the World Inequality Report. Over the same period, the share held by the bottom 50% plunged from 23% to just 15%.

Unsurprisingly, some feel resentful. “You walk around the streets of this city, and the rage at Antilia has to be heard to be believed,” Meera Sanyal, a former international banker turned local anti-corruption campaigner, told me in 2014. Six years before that, in 2008, as the scale of India’s billionaire fortunes were becoming clear, Raghuram Rajan – an economist who would later become the head of India’s central bank – asked an even more pointed question about his country’s tycoon class: “If Russia is an oligarchy, how long can we resist calling India one?”

Back in London, Vijay Mallya feels unjustly targeted by India’s recent attempts to shed its reputation for crony capitalism, the second defining characteristic of the billionaire Raj. “I have been accused by politicians and the media alike of having stolen and run away with Rs 9,000 crores [90bn rupees, or $1.3bn] that was loaned to Kingfisher Airlines,” he wrote in his open letter last month. His case had become, he suggested, a “lightning rod for public anger” over the alleged misbehaviour of his fellow tycoons.

In spring 2017, I met Mallya at his London home, a Grade I-listed town house a short walk from Baker Street tube station. A variety of Rolls-Royces and Bentleys were parked along the mews at the rear, alongside a fat silver Maybach with the number plate VJM 1, which idled outside Mallya’s back door. Inside, he sheltered behind a grand wooden table, a gold lighter and two mobile phones lined up in front of him. At one point I asked to be excused to visit the toilet. A flunky ushered me into a golden bathroom, with a shiny gold seat to match its golden taps and loo-roll holder. The fluffy hand towels were white, but each one came embossed with the letters “VJM” in gold thread.

On the surface, Mallya still seemed every bit the ebullient tycoon of old: a bulky man in a red polo shirt, with gold bracelets on each wrist and a chunky diamond ear stud. But by then he had been stuck in Britain for more than a year, and grew downbeat as the afternoon wound on and our conversation turned to his business troubles and the state of his homeland. “India has corruption running in its veins,” he said with a sigh. “And that’s not something one is going to change overnight.”

With his shoulder-length hair and taste for bling, Mallya had long honed an image as the most piratical of India’s generation of entrepreneurs. A specially kitted-out Boeing 727, its bar well-stocked with his own Kingfisher beer, whisked him between parties and business meetings – a distinction that was, in any case, often hazy. “It was all a bit ridiculous,” one ex-board member at a Mallya company told me.

Advertisement

Ambani owns Reliance Industries, an empire with interests stretching from petrochemicals to telecoms. (His father, Dhirubhai, from whom he inherited his company, was one of the main beneficiaries of the economic reforms of the 1980s.) At Antilia, Ambani entertains guests in a grand, chandeliered ballroom that takes up most of building’s ground floor. There are six storeys of parking for the family’s car collection, while the tower’s higher levels feature opulent apartments and hanging gardens. Further down, in sub-basement 2, the Ambanis keep a recreational floor, which includes an indoor football pitch. Antilia became an instant landmark upon its completion in 2010. The city had long been a place of stark divisions, yet the Ambani’s home almost seemed to magnify this segregation. (A spokesman for Reliance did not respond to a request for comment.)

The emergence of the Indian super-rich was bound up in larger global story. The early 2000s were the heyday of the so-called “great moderation”, when world interest rates stayed low and industrialised nations grew handsomely. This was also when the fortunes of India’s new tycoons began to change. Pumped up by foreign money, domestic bank loans and a surging sense of self-belief, industrialists went on a spending spree. Ambani dumped billions into oil refineries and petrochemical plants. Vijay Mallya spent heavily on new fleets of Airbus jets. Nirav Modi began building a global chain of jewellery stores. Stock markets boomed. From 2004 to 2014, India enjoyed the fastest expansion in its history, averaging growth of more than 8% a year.

The boom years brought benefits, most obviously by reintegrating India into the world economy. Yet this whirlwind growth also proved economically disruptive, socially bruising and environmentally destructive, leaving behind what the writer Rana Dasgupta describes as a sense of national trauma. India’s new wealth has been shared remarkably unevenly, too. Its richest 1% earned about 7% of national income in 1980; that figure rocketed to 22% by 2014, according to the World Inequality Report. Over the same period, the share held by the bottom 50% plunged from 23% to just 15%.

Unsurprisingly, some feel resentful. “You walk around the streets of this city, and the rage at Antilia has to be heard to be believed,” Meera Sanyal, a former international banker turned local anti-corruption campaigner, told me in 2014. Six years before that, in 2008, as the scale of India’s billionaire fortunes were becoming clear, Raghuram Rajan – an economist who would later become the head of India’s central bank – asked an even more pointed question about his country’s tycoon class: “If Russia is an oligarchy, how long can we resist calling India one?”

Back in London, Vijay Mallya feels unjustly targeted by India’s recent attempts to shed its reputation for crony capitalism, the second defining characteristic of the billionaire Raj. “I have been accused by politicians and the media alike of having stolen and run away with Rs 9,000 crores [90bn rupees, or $1.3bn] that was loaned to Kingfisher Airlines,” he wrote in his open letter last month. His case had become, he suggested, a “lightning rod for public anger” over the alleged misbehaviour of his fellow tycoons.

In spring 2017, I met Mallya at his London home, a Grade I-listed town house a short walk from Baker Street tube station. A variety of Rolls-Royces and Bentleys were parked along the mews at the rear, alongside a fat silver Maybach with the number plate VJM 1, which idled outside Mallya’s back door. Inside, he sheltered behind a grand wooden table, a gold lighter and two mobile phones lined up in front of him. At one point I asked to be excused to visit the toilet. A flunky ushered me into a golden bathroom, with a shiny gold seat to match its golden taps and loo-roll holder. The fluffy hand towels were white, but each one came embossed with the letters “VJM” in gold thread.

On the surface, Mallya still seemed every bit the ebullient tycoon of old: a bulky man in a red polo shirt, with gold bracelets on each wrist and a chunky diamond ear stud. But by then he had been stuck in Britain for more than a year, and grew downbeat as the afternoon wound on and our conversation turned to his business troubles and the state of his homeland. “India has corruption running in its veins,” he said with a sigh. “And that’s not something one is going to change overnight.”

With his shoulder-length hair and taste for bling, Mallya had long honed an image as the most piratical of India’s generation of entrepreneurs. A specially kitted-out Boeing 727, its bar well-stocked with his own Kingfisher beer, whisked him between parties and business meetings – a distinction that was, in any case, often hazy. “It was all a bit ridiculous,” one ex-board member at a Mallya company told me.

Vijay Mallya, who fled India for London in 2016. Photograph: Mark Thompson/Getty Images

Now marooned in London, Mallya had plenty of time to ponder his missteps. Once a member of the Rajya Sabha, the Indian upper house of parliament, his diplomatic passport has been cancelled. As a long-time UK resident, he was permitted to stay in the country, but without travel documents he was unable to travel, curtailing his notorious jetsetting lifestyle almost entirely. Earlier this month, a UK court issued an order allowing authorities trying to recover debts to enter his various British properties.

In his pomp, Mallya seemed to represent a new India. In a country whose old commercial elite had been dominated by cautious, discreet industrialists, Mallya was different: rich, powerful and not inclined to hide it. Not all of India’s pioneers behaved in this way – its software and IT billionaires, for instance, were typically less flamboyant figures. But while Mallya continues to deny that he did anything wrong, he admits that he has become what he calls the “poster boy” for a moment of public anger against India’s rich, as many newly wealthy business figures found themselves mired in allegations of wrongdoing.

India’s old system created fertile ground for corruption, forcing citizens and businesses alike to pay myriad bribes for basic state services. But these humdrum problems were trivial compared with the grand scandals that emerged during the 2000s. Assets worth billions were gifted under the table to big tycoons by senior politicians and bureaucrats in what became known as the “season of scams”. Giant kickbacks helped businesses acquire land, bypass environmental rules and win infrastructure contracts. Headlines filled up with fresh outrages, from fraudulent public housing schemes to dodgy road-building projects.

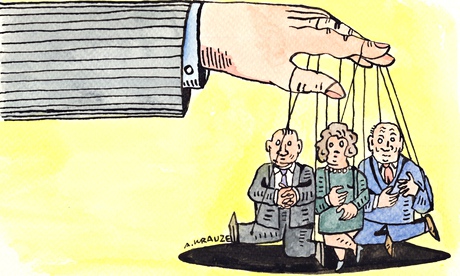

Many of those who backed India’s economic reforms hoped that a more free-market economy would lead to more honest government. Instead, crony capitalism infiltrated almost every area of national life. Hundreds of billions of dollars were siphoned away, according to some estimates, by a shadowy alliance of colluding politicians and business tycoons. India’s old system of retail corruption went wholesale.

Many politicians also became astoundingly rich, and would have made the Forbes list had their holdings not been hidden carefully in shell companies and foreign banks. Rapid economic growth increased the value of political power, and what could be extracted from it. Political parties had to raise more money, to fight elections and fund the patronage that kept them in office. One estimate suggested that India’s 2014 election cost close to $5bn, a huge increase over the cheap and cheerful polls of the pre-liberalisation era. Election experts believe most of this money is brought in illegally from favoured tycoons, in exchange for unknown future favours.

Politicians spend the money to fund campaigns, but also on handing out favours, jobs and cash to constituents. “It’s sort of an unholy nexus,” as Raghuram Rajan put it to me during his tenure as head of India’s central bank. “Poor public services? Politician fills the gap; politician gets the resources from the businessman; politician gets re-elected by the electorate for whom he’s filling the gap.”

This nexus between business and politics lies at the heart of the third problem of India’s billionaire Raj, namely the boom-and-bust cycle of its industrial economy. In recent decades, China went on the largest infrastructure building spree in history, but almost all of it was delivered by state-backed companies. By contrast, India’s mid-2000s boom was dominated almost exclusively by its private-sector tycoons, giving the industrialists and the conglomerates they run a position of outsized importance in India’s economic development.

Bollygarchs borrowed huge sums from state-backed banks and invested with gleeful abandon, in one of the largest deployments of private capital since America built its railroad network 150 years earlier. But when India’s good times came to an end after the global financial crisis, the tycoons’ hubris was exposed, leaving their businesses over-stretched and struggling to repay their debts. In 2017, 10 years on from the crisis, India’s banks were still left holding at least $150bn of bad assets.

Since taking office, Narendra Modi has tried, often ineffectually, to fix this corporate- and bank-debt crisis, alongside the related problems of cronyism and the super-rich that contributed to it. Watching developments such as these, some argue that the power of India’s tycoon class is fading. Yet India’s ultra-wealthy are still thriving, while its ranks of billionaires keep swelling, and will continue to do so.

There is every reason to believe that on its current course, the country’s the gap between rich and poor will widen, too. Perversely, the closer India comes to its achieving its ambitions of Chinese-style double-digit levels of economic growth, the faster this will happen. On most measures, it should already be ranked alongside South Africa and Brazil as one of the world’s least-equal countries. Even more importantly, poor countries that start off with high levels of inequality often struggle to reverse that trend as they grow richer.

Many experts believe India needs to act. “The main danger with extreme inequality is that if you don’t solve this through peaceful and democratic institutions then it will be solved in other ways … and that’s extremely frightening,” as French economist Thomas Piketty has said of India’s future, pointing to likely rising future tensions between the wealthy and the rest.

Now marooned in London, Mallya had plenty of time to ponder his missteps. Once a member of the Rajya Sabha, the Indian upper house of parliament, his diplomatic passport has been cancelled. As a long-time UK resident, he was permitted to stay in the country, but without travel documents he was unable to travel, curtailing his notorious jetsetting lifestyle almost entirely. Earlier this month, a UK court issued an order allowing authorities trying to recover debts to enter his various British properties.

In his pomp, Mallya seemed to represent a new India. In a country whose old commercial elite had been dominated by cautious, discreet industrialists, Mallya was different: rich, powerful and not inclined to hide it. Not all of India’s pioneers behaved in this way – its software and IT billionaires, for instance, were typically less flamboyant figures. But while Mallya continues to deny that he did anything wrong, he admits that he has become what he calls the “poster boy” for a moment of public anger against India’s rich, as many newly wealthy business figures found themselves mired in allegations of wrongdoing.

India’s old system created fertile ground for corruption, forcing citizens and businesses alike to pay myriad bribes for basic state services. But these humdrum problems were trivial compared with the grand scandals that emerged during the 2000s. Assets worth billions were gifted under the table to big tycoons by senior politicians and bureaucrats in what became known as the “season of scams”. Giant kickbacks helped businesses acquire land, bypass environmental rules and win infrastructure contracts. Headlines filled up with fresh outrages, from fraudulent public housing schemes to dodgy road-building projects.

Many of those who backed India’s economic reforms hoped that a more free-market economy would lead to more honest government. Instead, crony capitalism infiltrated almost every area of national life. Hundreds of billions of dollars were siphoned away, according to some estimates, by a shadowy alliance of colluding politicians and business tycoons. India’s old system of retail corruption went wholesale.

Many politicians also became astoundingly rich, and would have made the Forbes list had their holdings not been hidden carefully in shell companies and foreign banks. Rapid economic growth increased the value of political power, and what could be extracted from it. Political parties had to raise more money, to fight elections and fund the patronage that kept them in office. One estimate suggested that India’s 2014 election cost close to $5bn, a huge increase over the cheap and cheerful polls of the pre-liberalisation era. Election experts believe most of this money is brought in illegally from favoured tycoons, in exchange for unknown future favours.

Politicians spend the money to fund campaigns, but also on handing out favours, jobs and cash to constituents. “It’s sort of an unholy nexus,” as Raghuram Rajan put it to me during his tenure as head of India’s central bank. “Poor public services? Politician fills the gap; politician gets the resources from the businessman; politician gets re-elected by the electorate for whom he’s filling the gap.”

This nexus between business and politics lies at the heart of the third problem of India’s billionaire Raj, namely the boom-and-bust cycle of its industrial economy. In recent decades, China went on the largest infrastructure building spree in history, but almost all of it was delivered by state-backed companies. By contrast, India’s mid-2000s boom was dominated almost exclusively by its private-sector tycoons, giving the industrialists and the conglomerates they run a position of outsized importance in India’s economic development.

Bollygarchs borrowed huge sums from state-backed banks and invested with gleeful abandon, in one of the largest deployments of private capital since America built its railroad network 150 years earlier. But when India’s good times came to an end after the global financial crisis, the tycoons’ hubris was exposed, leaving their businesses over-stretched and struggling to repay their debts. In 2017, 10 years on from the crisis, India’s banks were still left holding at least $150bn of bad assets.

Since taking office, Narendra Modi has tried, often ineffectually, to fix this corporate- and bank-debt crisis, alongside the related problems of cronyism and the super-rich that contributed to it. Watching developments such as these, some argue that the power of India’s tycoon class is fading. Yet India’s ultra-wealthy are still thriving, while its ranks of billionaires keep swelling, and will continue to do so.

There is every reason to believe that on its current course, the country’s the gap between rich and poor will widen, too. Perversely, the closer India comes to its achieving its ambitions of Chinese-style double-digit levels of economic growth, the faster this will happen. On most measures, it should already be ranked alongside South Africa and Brazil as one of the world’s least-equal countries. Even more importantly, poor countries that start off with high levels of inequality often struggle to reverse that trend as they grow richer.

Many experts believe India needs to act. “The main danger with extreme inequality is that if you don’t solve this through peaceful and democratic institutions then it will be solved in other ways … and that’s extremely frightening,” as French economist Thomas Piketty has said of India’s future, pointing to likely rising future tensions between the wealthy and the rest.

Protesters burning an effigy of Nirav Modi in New Delhi in February. Photograph: Chandan Khanna/AFP/Getty Images

India is now entering a new phase of development, as it tries to follow Asian economies such as South Korea and Malaysia out of poverty and towards full “middle-income” status. There is no reason this cannot happen. But as we’ve seen in Latin America, the economies with the widest social divides have tended to be the ones that are most likely to get stuck in the “middle-income trap”, achieving moderate prosperity but failing to become rich. The more successful countries of east Asia, by contrast, grew prosperous while managing to stay egalitarian, partly by building basic social safety nets and ensuring that their wealthiest citizens paid their taxes. Of the two models, it seems clear which India should want to follow.

Much the same is true of corruption. India’s old system of cronyism, with its political favours and risk-free bank loans, has came under intense scrutiny, but the battle against corruption is at best half-won. Kickbacks still dominate swathes of public life, from land purchase to municipal contracts. State and city governments are just as venal as ever. Surveys report that India remains Asia’s most bribe-ridden nation. “For any society to lift itself out of absolute poverty, it needs to build three critical state institutions: taxation, law and security,” according to the economist Paul Collier. All three in India – the revenue service, the lower levels of the judiciary and the police – still suffer endemic corruption. Perhaps most importantly, the country’s under-the-table political funding system remains largely untouched.

Progress in fixing India’s problems of corporate and bank debt has also been frustratingly slow. Modi has introduced some important measures, including a new bankruptcy law and a series of bank recapitalisations. But more radical options have been ignored, notably the privatisation of struggling public-sector lenders.

If these struggles sound familiar, that is because they are. India is far from the first country to enjoy a period of rampant cronyism and wild growth, and then grapple with how to respond. In Britain, the onset of the industrial revolution in the mid-19th century kicked off such a moment, as captured in the novels of Charles Dickens and Anthony Trollope. But the more obvious parallel is with America, and the era between the end of the civil war in 1865 and the turn of the 20th century: the Gilded Age, or the era of “the great corporation, the crass plutocrat [and] the calculating political boss”, as one historian put it.

India’s own Gilded Age is different in many ways, but it shares at least one characteristic – namely, that such a period of early industrialisation is also a time of rapid political and economic change, in which it should be possible to invoke what the philosopher Richard Rorty once called the “romance of a national future”, the sense of hope that infuses powers on the rise.

India is set to grow in economic might throughout this century, as America did during the 19th. By some accounts, it has already overtaken China as the world’s most populous nation; in others, the baton will pass during the next decade or two. Whatever the case, the fate of a large slice of humanity depends on India getting its economic model right. Meanwhile, as democracy falters in the west, so its future in India has never been more critical. To make this transition, India’s billionaire Raj must become a passing phase, not a permanent condition. India’s ambition to lead the second half of the “Asian century” – and the world’s hopes for a fairer and more democratic future – depend on getting this transition right.

India is now entering a new phase of development, as it tries to follow Asian economies such as South Korea and Malaysia out of poverty and towards full “middle-income” status. There is no reason this cannot happen. But as we’ve seen in Latin America, the economies with the widest social divides have tended to be the ones that are most likely to get stuck in the “middle-income trap”, achieving moderate prosperity but failing to become rich. The more successful countries of east Asia, by contrast, grew prosperous while managing to stay egalitarian, partly by building basic social safety nets and ensuring that their wealthiest citizens paid their taxes. Of the two models, it seems clear which India should want to follow.

Much the same is true of corruption. India’s old system of cronyism, with its political favours and risk-free bank loans, has came under intense scrutiny, but the battle against corruption is at best half-won. Kickbacks still dominate swathes of public life, from land purchase to municipal contracts. State and city governments are just as venal as ever. Surveys report that India remains Asia’s most bribe-ridden nation. “For any society to lift itself out of absolute poverty, it needs to build three critical state institutions: taxation, law and security,” according to the economist Paul Collier. All three in India – the revenue service, the lower levels of the judiciary and the police – still suffer endemic corruption. Perhaps most importantly, the country’s under-the-table political funding system remains largely untouched.

Progress in fixing India’s problems of corporate and bank debt has also been frustratingly slow. Modi has introduced some important measures, including a new bankruptcy law and a series of bank recapitalisations. But more radical options have been ignored, notably the privatisation of struggling public-sector lenders.

If these struggles sound familiar, that is because they are. India is far from the first country to enjoy a period of rampant cronyism and wild growth, and then grapple with how to respond. In Britain, the onset of the industrial revolution in the mid-19th century kicked off such a moment, as captured in the novels of Charles Dickens and Anthony Trollope. But the more obvious parallel is with America, and the era between the end of the civil war in 1865 and the turn of the 20th century: the Gilded Age, or the era of “the great corporation, the crass plutocrat [and] the calculating political boss”, as one historian put it.

India’s own Gilded Age is different in many ways, but it shares at least one characteristic – namely, that such a period of early industrialisation is also a time of rapid political and economic change, in which it should be possible to invoke what the philosopher Richard Rorty once called the “romance of a national future”, the sense of hope that infuses powers on the rise.

India is set to grow in economic might throughout this century, as America did during the 19th. By some accounts, it has already overtaken China as the world’s most populous nation; in others, the baton will pass during the next decade or two. Whatever the case, the fate of a large slice of humanity depends on India getting its economic model right. Meanwhile, as democracy falters in the west, so its future in India has never been more critical. To make this transition, India’s billionaire Raj must become a passing phase, not a permanent condition. India’s ambition to lead the second half of the “Asian century” – and the world’s hopes for a fairer and more democratic future – depend on getting this transition right.

Sunday, 8 July 2018

The Billionaire Raj: A chronicle of economic India

Meghnad Desai in The FT

India is now one of the world’s economic hotspots. Stock images of starving children, miserable peasants and cheating shop owners have been augmented with those of high-tech development and booming cities. India is now the world’s fastest-growing economy. It is about to become the third-largest economy — at least in terms of purchasing power dollars if not yet real ones. Foreign investors are rushing in. In The Billionaire Raj, James Crabtree has written a compelling guide to what awaits them.

To make India more accessible to the western investor, Crabtree draws an analogy between America’s Gilded Age at the end of the 19th century — that plutocratic moment of the Vanderbilts, Goulds, Rockefellers — and the newest of India’s billionaires. Did you know that India now has more billionaires than Russia?

This sudden enrichment was the result of the long boom of globalisation from 1991-2008. India had initiated reforms to escape from four decades of conservative socialism, initiated by Jawaharlal Nehru, which did not trust private business and put the state in command. The Indian state is inefficient as it is, but disastrous in running business. Its airline Air India has racked up billions in losses; its banks are mired in non-performing loans.

In 1991, Manmohan Singh, then finance minister, bit the bullet and began to liberalise the economy. Tariffs were cut, import licensing was removed, and the rupee was devalued twice within a week. He had little choice because India had run out of foreign exchange reserves and had to pawn its gold to secure a loan from the International Monetary Fund.

The reforms took time to work but, from 1998 onwards, the economy secured high single-digit growth rates, triple the so-called “Hindu growth rate” of 3 per cent per year that prevailed during the first 30 years of independence. With a decade-long growth spurt from 1998 to 2008 came the vast fortunes generated in a crony-capitalist relationship between the ruling Congress party and its private sector clients and financiers. Crabtree, a former FT Mumbai correspondent, gives us a detailed treatment of the links between the politicians needing money to finance elections that were both costly and cheap. (The 2014 elections cost $5bn — or $6 per voter.)

Crabtree gives entertaining portraits of some billionaires. The opening chapters cover Mukesh Ambani and his towering residential extravaganza Antilla, the most expensive house ever built in India, which now dominates the Mumbai skyline; the fugitive Vijay Mallya, a drinks tycoon who was once known as the King of Good Times; the reticent Gautam Adani, an infrastructure entrepreneur who owns ports, mines and refineries. Dhirubhai Ambani, the patriarch of the Reliance group, figured out how to negotiate government regulations and expand his business while keeping the ruling party on his side. Mallya went so far as to be voted into a seat in the Rajya Sabha, the upper house of parliament, after a reported donation of 550m rupees ($10m in those days). Adani prospered in Gujarat with the reported blessings of Narendra Modi while he was chief minister of the state in India’s north-west, where the politician enjoyed both a clean reputation and business-friendly credentials.

Crabtree shows both how deep corruption reaches into electoral politics — but also how functional it is

Beyond the personalities lies another part of the puzzle. Corruption has gone deep in the system. Elections cannot be financed with just legally declared donations. The donors want to escape attention of the tax man, as do the party leaders. It is a symbiotic relationship. Not even Prime Minister Modi, as he has been since 2014, is about to change it, though he has moved against crony capitalism. Armed with an electoral majority, he has set about breaking the political mould, ending the near 70-year hegemony of Congress. He has sundered the crony ties that the top echelon of government enjoyed with the “promoters” of infrastructure projects during the Congress years. Back then the nationalised banks had to lend money to a favoured few and it was understood that the money would not be repaid. No more. Insolvency procedures have been toughened. Debtors can no longer shield their assets from creditors. It was this that sent Mallya abroad.

This book was written before these drastic changes. But whether he wins or loses the next elections, Modi has made revival of crony capitalism difficult.

There are also other concerns. Crabtree worries over Modi’s dual persona as a development enthusiast as well as a Hindu nationalist. The fear is that this may increase intolerance towards minorities — Muslims and Christians — and disrupt peaceful economic progress.

Crabtree’s vivid portrayal of the corruption of politics is very informative, and thought-provoking. He travels the country to show both how deep corruption reaches into electoral politics — but also how functional it is. When an economy is regulated, riddled with permits needed to do business, a few palms may need to be greased. A payment — or rent, as economists call it — may be required. But the rewards are considerable. The corruption market works. It may be immoral but it is not inefficient.

It would be better if India became less corrupt. Crabtree thinks so. That would require a lot of courage and an ability to pursue radical reform. The leader who embarks upon it risks unpopularity — as Modi is now finding out.

These are matters that cannot be settled in a single book. Crabtree has given us the most comprehensive and eminently readable tour of economic India, which, as he shows, cannot be understood without a knowledge of how political India works.

India is now one of the world’s economic hotspots. Stock images of starving children, miserable peasants and cheating shop owners have been augmented with those of high-tech development and booming cities. India is now the world’s fastest-growing economy. It is about to become the third-largest economy — at least in terms of purchasing power dollars if not yet real ones. Foreign investors are rushing in. In The Billionaire Raj, James Crabtree has written a compelling guide to what awaits them.

To make India more accessible to the western investor, Crabtree draws an analogy between America’s Gilded Age at the end of the 19th century — that plutocratic moment of the Vanderbilts, Goulds, Rockefellers — and the newest of India’s billionaires. Did you know that India now has more billionaires than Russia?

This sudden enrichment was the result of the long boom of globalisation from 1991-2008. India had initiated reforms to escape from four decades of conservative socialism, initiated by Jawaharlal Nehru, which did not trust private business and put the state in command. The Indian state is inefficient as it is, but disastrous in running business. Its airline Air India has racked up billions in losses; its banks are mired in non-performing loans.

In 1991, Manmohan Singh, then finance minister, bit the bullet and began to liberalise the economy. Tariffs were cut, import licensing was removed, and the rupee was devalued twice within a week. He had little choice because India had run out of foreign exchange reserves and had to pawn its gold to secure a loan from the International Monetary Fund.

The reforms took time to work but, from 1998 onwards, the economy secured high single-digit growth rates, triple the so-called “Hindu growth rate” of 3 per cent per year that prevailed during the first 30 years of independence. With a decade-long growth spurt from 1998 to 2008 came the vast fortunes generated in a crony-capitalist relationship between the ruling Congress party and its private sector clients and financiers. Crabtree, a former FT Mumbai correspondent, gives us a detailed treatment of the links between the politicians needing money to finance elections that were both costly and cheap. (The 2014 elections cost $5bn — or $6 per voter.)