'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Saturday, 8 April 2023

Wednesday, 6 April 2022

Will dollar dominance give way to a multipolar system of currencies?

From The Economist

In the wake of an invasion that drew international condemnation, Russian officials panicked that their dollar-denominated assets within America’s reach were at risk of abrupt confiscation, sending them scrambling for alternatives. The invasion in question did not take place in 2022, or even 2014, but in 1956, when Soviet tanks rolled into Hungary. The event is often regarded as one of the factors that helped kick-start the eurodollar market—a network of dollar-denominated deposits held outside America and usually beyond the direct reach of its banking regulators.

The irony is that the desire to keep dollars outside America only reinforced the greenback’s heft. As of September, banks based outside the country reported around $17trn in dollar liabilities, twice as much as the equivalent for all the other currencies in the world combined. Although eurodollar deposits are beyond Uncle Sam’s direct control, America can still block a target’s access to the dollar system by making transacting with them illegal, as its latest measures against Russia have done.

This fresh outbreak of financial conflict has raised the question of whether the dollar’s dominance has been tarnished, and whether a multipolar currency system will rise instead, with the Chinese yuan playing a bigger role. To understand what the future might look like, it is worth considering how the dollar’s role has evolved over the past two decades. Its supremacy reflects more than the fact that America’s economy is large and its government powerful. The liquidity, flexibility and the reliability of the system have helped, too, and are likely to help sustain its global role. In the few areas where the dollar has lost ground, the characteristics that made it king are still being sought out by holders and users—and do not favour the yuan.

Eurodollar deposits illustrate the greenback’s role as a global store of value. But that is not the only thing that makes the dollar a truly international currency. Its role as a unit of account, in the invoicing of the majority of global trade, may be its most overwhelming area of dominance. According to research published by the imf in 2020, over half of non-American and non-eu exports are denominated in dollars. In Asian emerging markets and Latin America the share rises to roughly 75% and almost 100%, respectively. Barring a modest increase in euro invoicing by some European countries that are not part of the currency union, these figures have changed little in the past two decades.

Another pillar of the dollar’s dominance is its role in cross-border payments, as a medium of exchange. A lack of natural liquidity for smaller currency pairs means that it often acts as a vehicle currency. A Uruguayan importer might pay a Bangladeshi exporter by changing her peso into dollars, and changing those dollars into taka, rather than converting the currencies directly.

So far there has been little shift away from the greenback: in February only one transaction in every five registered by the swift messaging system did not have a dollar leg, a figure that has barely changed over the past half-decade. But a drift away is not impossible. Smaller currency pairs could become more liquid, reducing the need for an intermediary. Eswar Prasad of Cornell University argues convincingly that alternative payment networks, like China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System, might undermine the greenback’s role. He also suggests that greater use of digital currencies will eventually reduce the need for the dollar. Those developed by central banks in particular could facilitate a direct link between national payment systems.

Perhaps the best example in global finance of an area in which the dollar is genuinely and measurably losing ground is central banks’ foreign-exchange reserves. Research published in March by Barry Eichengreen, an economic historian at the University of California, Berkeley, shows how the dollar’s presence in central-bank reserves has declined. Its share slipped from 71% of global reserves in 1999 to 59% in 2021. The phenomenon is widespread across a variety of central banks, and cannot be explained away by movements in exchange rates.

The findings reveal something compelling about the dollar’s new competitors. The greenback’s lost share has largely translated into a bigger share for what Mr Eichengreen calls “non-traditional” reserve currencies. The yuan makes up only a quarter of this group’s share in global reserves. The Australian and Canadian dollars, by comparison, account for 43% of it. And the currencies of Denmark, Norway, South Korea and Sweden make up another 23%. The things that unite those disparate smaller currencies are clear: all are floating and issued by countries with relatively or completely open capital accounts and governed by reliable political systems. The yuan, by contrast, ticks none of those boxes. “Every reserve currency in history has been a leading democracy with checks and balances,” says Mr Eichengreen.

Battle royal

Though the discussion of whether the dollar might be supplanted by the yuan captures the zeitgeist of great-power competition, the reality is more prosaic. Capital markets in countries with predictable legal systems and convertible currencies have deepened, and many offer better risk-adjusted returns than Treasuries. That has allowed reserve managers to diversify without compromising on the tenets that make reserve currencies dependable.

Mr Eichengreen’s research also speaks to a plain truth with a broader application: pure economic heft is not nearly enough to build an international currency system. Even where the dollar’s dominance looks most like it is being chipped away, the appetite for the yuan to take even a modest share of its place looks limited. Whether the greenback retains its paramount role in the international monetary system or not, the holders and users of global currencies will continue to prize liquidity, flexibility and reliability. Not every currency can provide them.

Sunday, 3 April 2022

Friday, 26 March 2021

Wednesday, 27 January 2016

China accuses George Soros of 'declaring war' on yuan

Agence France-Presse in Beijing

Wednesday 27 January 2016 06.04 GMT

Chinese state media has stepped up a salvo of biting commentaries against George Soros and other currency traders as the yuan comes under pressure, with the billionaire investor accused of “declaring war” on the unit.

At the annual World Economic Forum in Davos last week, Soros told Bloomberg TV that the world’s second-largest economy – where growth has already slowed to a 25-year low according to official figures – was heading for more troubles.

“A hard landing is practically unavoidable,” he said.

Global markets turmoil echoes 2008 financial crisis, warns George Soros

Soros – whose enormous trades are still blamed in some countries for contributing to the Asian financial crisis of 1997 – pointed to deflation and excessive debt as reasons for China’s slowdown.

The normally stable yuan, whose value is closely controlled by Beijing, has come under pressure in recent weeks and months in overseas markets and from capital outflows. Authorities have spent hundreds of billions of dollars to defend it.

China’s official Xinhua news agency on Wednesday said that Soros had predicted economic troubles for China “several times in the past”.

“Either the short-sellers haven’t done their homework or … they are intentionally trying to create panic to snap profits,” it said.

An English-language op-ed in the nationalistic Global Times newspaper blamed “westerners” for not “accepting responsibility for the mess” in the world economy.

The comments came after the overseas edition of the People’s Daily, the official mouthpiece of the Communist party, published a front-page article Tuesday titled “Declaring war on China’s currency? Ha ha” that was widely shared on Chinese social media.

Soros “publicly ‘declared war’ on China”, the paper said, citing the 85-year-old as saying that he had taken positions against Asian currencies.

But some readers questioned whether the official rhetoric could fuel Chinese investors’ fears.

“They say a lot of loud slogans, but do official media even know that Chinese investors are in hell?” said one poster on social media network Weibo.

“I’m afraid that Chinese investors will die in a stampede before Soros even shows his hand.”

In the 1990s Soros led speculators in bets against the Bank of England, which unsuccessfully sought to defend the pound’s exchange rate peg.

“The Chinese left it too long” to change their growth model from dependence on exports to a consumer-led one, Soros said, even though Beijing had “greater latitude” than others to manage such a transition because of its currency reserves, which stand at over US$3tn.

Tuesday, 22 December 2015

Zimbabwe to make Chinese yuan legal currency after Beijing cancels debts

Agence France-Presse

Zimbabwe has announced that it will make the Chinese yuan legal tender after Beijing confirmed it would cancel $40m in debts.

“They [China] said they are cancelling our debts that are maturing this year and we are in the process of finalising the debt instruments and calculating the debts,” minister Patrick Chinamasa said in a statement.

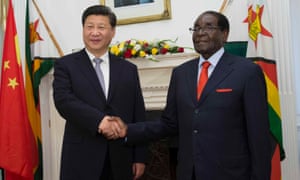

Robert Mugabe greets China's Xi Jinping as 'true and dear friend' of Zimbabwe

Chinamasa also announced that Zimbabwe will officially make the Chinese yuan legal tender as it seeks to increase trade with Beijing.

Zimbabwe abandoned its own dollar in 2009 after hyperinflation, which had peaked at around 500bn%, rendered it unusable.

It then started using a slew of foreign currencies, including the US dollar and the South African rand.

The yuan was later added to the basket of the foreign currencies, but its use had not been approved yet for public transactions in the market dominated by the greenback.

Use of the yuan “will be a function of trade between China and Zimbabwe and acceptability with customers in Zimbabwe,” the minister said.

Zimbabwe’s central bank chief John Mangudya was in negotiations with the People’s Bank of China “to see whether we can enhance its usage here,” said Chinamasa.

China is Zimbabwe’s biggest trading partner following Zimbabwe’s isolation by its former western trading partners over Harare’s human rights record.

In reaction veteran president Robert Mugabe adopted a “look East policy”, forging new alliances with eastern Asian countries and buttressing existing ones.

In early December, Chinese president Xi Jinping stopped over in Zimbabwe in a rare trip by a world leader to the country, and presided over the signing of various agreements, mainly to upgrade and rebuild Zimbabwe’s infrastructure such as power stations.

Friday, 21 August 2015

Currency wars in emerging markets hammer global stocks

Developing world devaluations have sent global

In response to China’s surprise devaluation of the yuan last week, several emerging market

Kazakhstan’s tenge lost 24 per cent of its value against the dollar after the country’s central bank announced that it would allow the currency to float freely. Meanwhile, South Africa’s rand slid to its weakest level against the dollar in 14 years and Malaysia’s ringgit fell to its lowest level against the greenback in 17 years. Turkey’s lira and the Russian rouble also dropped.

This followed the decision by Vietnam on Wednesday to cut the value of the dong against the dollar by 1 per cent, the country’s third devaluation of the year. Since Beijing’s yuan devaluation last week, an index of 20 developing-nation exchange rates has been falling fast.

The ructions depressed the FTSE100, pushing the index down into technical “correction” territory, more than 10 per cent below its April peak. Year-to-date, the benchmark index of UK-listed shares, is down 2.9 per cent. The S&P 500 also quickly fell 1.2 per cent after trading opened in America, wiping out all of the US index’s gains made this year.

Last week, the People’s Bank of China caught markets

“The appearance of China weakening its exchange rate to boost growth has added urgency for policymakers elsewhere to do what they can to grab more export revenue” said Koon Chow, of Union Bancaire Privée.

Many analysts expect further global devaluations if the US Federal Reserve, as expected, increases interest rates for the first time since the financial crisis later this year. “Emerging market currencies, in general, still have high devaluation risks” said analysts at CrossBorder Capital. Analysts predicted the likes of Egypt and Nigeria could be next to devalue their currencies.

Per Hammarlund, of Sweden’s SEB, said Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan could allow their currencies to depreciate by between 10 and 20 per cent. “They simply don’t have much of a choice but to follow Russia and emerging markets

Capital has been flowing out of emerging markets at a rapid rate this year, as fears rise of a sharp slowdown in the former stars of the global economy. Over the past 13 months $1 trillion is estimated to have flowed out of the 19 largest emerging countries.

The International Monetary Fund expects global growth among emerging markets and developing economies to be just 4.2 per cent this year, the weakest output growth since 2009.

Nariman Behravesh, of IHS Global Insight, said emerging markets are arguably facing “the toughest environment since the Asia Crisis of the late 1990s” and predicted that they will drag on global growth into next year.

Thursday, 13 August 2015

China cannot risk the global chaos of currency devaluation

12 Aug 2015

If China really is trying to drive down its currency in any meaningful way to gain trade advantage, the world faces an extremely dangerous moment.

Such desperate behaviour would send a deflationary shock through a global economy already reeling from near recession earlier this year, and would risk a repeat of East Asia's currency crisis in 1998 on a larger planetary scale.

China's fixed investment reached $5 trillion last year, matching the whole of Europe and North America combined. This is the root cause of chronic overcapacity worldwide, from shipping, to steel, chemicals and solar panels.

A Chinese devaluation would export yet more of this excess supply to the rest of us. It is one thing to do this when global trade is expanding: it amounts to beggar-thy-neighbour currency warfare to do so in a zero-sum world with no growth at all in shipping volumes this year.

It is little wonder that the first whiff of this mercantilist threat has set off an August storm, ripping through global bourses. The Bloomberg commodity index has crashed to a 13-year low.

Europe and America have failed to build up adequate safety buffers against a fresh wave of imported deflation. Core prices are rising at a rate of barely 1pc on both sides of the Atlantic, a full six years into a mature economic cycle.

One dreads to think what would happen if we tip into a global downturn in these circumstances, with interest rates still at zero, quantitative easing played out, and aggregate debt levels 30 percentage points of GDP higher than in 2008.

"The world economy is sailing across the ocean without any lifeboats to use in case of emergency," said Stephen King from HSBC in a haunting reportin May.

Whether or not Beijing sees matters in this light, it knows that the US Congress would react very badly to any sign of currency warfare by a country that racked up a record trade surplus of $137bn in second quarter, an annual pace above 5pc of GDP. Only deficit states can plausibly justify resorting to this game.

Senators Schumer, Casey, Grassley, and Graham have all lined up to accuse Beijing of currency manipulation, a term that implies retaliatory sanctions under US trade law.

Any political restraint that Congress might once have felt is being eroded fast by evidence of Chinese airstrips and artillery on disputed reefs in the South China Sea, just off the Philippines.

It is too early to know for sure whether China has in fact made a conscious decision to devalue. Bo Zhuang from Trusted Sources said there is a "tug-of-war" within the Communist Party.

All the central bank (PBOC) has done so far is to switch from a dollar peg to a managed float. This is a step closer towards a free market exchange, and has been welcomed by the US Treasury and the International Monetary Fund.

The immediate effect was a 1.84pc fall in the yuan against the dollar on Tuesday, breathlessly described as the biggest one-day move since 1994. The PBOC said it was a merely "one-off" technical adjustment.

If so, one might also assume that the PBOC would defend the new line at 6.32 to drive home the point. What is faintly alarming is that the central bank failed to do so, letting the currency slide a further 1.6pc on Wednesday before reacting.

The PBOC put out a soothing statement, insisting that "currently there is no basis for persistent depreciation" of the yuan and that the economy is in any case picking up. So take your pick: conspiracy or cock-up.

The proof will now be in the pudding. The PBOC has $3.65 trillion reserves to prevent any further devaluation for the time being. If it does not do so, we may legitimately suspect that the State Council is in charge and has opted for covert currency warfare.

Personally, I doubt that this is the start of a long slippery slide. The risks are too high. Chinese companies have borrowed huge sums in US dollars on off-shore markets to circumvent lending curbs at home, and these are typically the weakest firms shut off from China's banking system.

Hans Redeker from Morgan Stanley says short-term dollar liabilities reached $1.3 trillion earlier this year. "This is 9.5pc of Chinese GDP. When short-term foreign debt reaches this level in emerging markets it is a perfect indicator of coming stress. It is exactly what we saw in the Asian crisis in the 1990s," he said.

Devaluation would risk setting off serious capital flight, far beyond the sort of outflows seen so far - with estimates varying from $400bn to $800bn over the last five quarters.

This could spin out of control easily if markets suspect that Beijing is itself fanning the flames. While the PBOC could counter outflows by running down reserves - as it is already doing to a degree, at a pace of $15bn a month - such a policy entails automatic monetary tightening and might make matters worse.

The slowdown in China is not yet serious enough to justify such a risk. True, the trade-weighted exchange rate has soared 22pc since mid-2012, the result of being strapped to a rocketing dollar at the wrong moment. The yuan is up 60pc against the Japanese yen.

This loss of competitiveness has been painful - and is getting worse as the shrinking supply of migrant labour from the countryside pushes up wages - but it was not the chief cause of the crunch in the first half of the year.

The economy hit a brick wall because monetary and fiscal policy were too tight. The authorities failed to act as falling inflation pushed one-year borrowing costs in real terms from zero in 2011 to 5pc by the end of 2014.

They also failed to anticipate a “fiscal cliff” earlier this year as official revenue from land sales collapsed, and local governments were prohibited from bank borrowing -- understandably perhaps given debts of $5 trillion, on some estimates.

The calibrated deleveraging by premier Li Keqiang simply went too far. He has since reversed course. The local government bond market is finally off the ground, issuing $205bn of new debt between May and July. This is serious fiscal stimulus.

Nomura says monetary policy is now as loose as in the depths of the post-Lehman crisis. Its 'growth surprise index' for China touched bottom in May and is now signalling a “strong rebound”.

Capital Economics said bank loans jumped to 15.5pc in June, the fastest pace since 2012. "There are already signs that policy easing is gaining traction," it said.

It is worth remembering that the authorities are no longer targeting headline growth. Their lode star these days is employment, a far more relevant gauge for the survival of the Communist regime. On this score, there is no great drama. The economy generated 7.2m extra jobs in the first half half of 2015, well ahead of the 10m annual target.

Few dispute that China is in trouble. Credit has been stretched to the limit and beyond. The jump in debt from 120pc to 260pc of GDP in seven years is unprecedented in any major economy in modern times.

For sheer intensity of credit excess, it is twice the level of Japan's Nikkei bubble in the late 1980s, and I doubt that it will end any better. At least Japan was already rich when it let rip. China faces much the same demographic crisis before it crosses the development threshold.

It is in any case wrestling with an impossible contradiction: aspiring to hi-tech growth on the economic cutting edge, yet under top-down Communist party control and spreading repression. That way lies the middle income trap, the curse of all authoritarian regimes that fail to reform in time.

Yet this is a story for the next fifteen years. The Communist Party has not yet run out of stimulus and is clearly deploying the state banking system to engineer yet another mini-cycle right now. One day China will pull the lever and nothing will happen. We are not there yet.

Saturday, 12 November 2011

China's richest keep firm eye on exit door

By Olivia Chung

HONG KONG - "Get rich - then get out" is the life message being grasped by China's wealthiest citizens two decades after former leader Deng Xiaoping supposedly declared that "to get rich is glorious".

About 60% of rich Chinese people intend to migrate from China, according to a report jointly released by the Hurun Report, which also publishes an annual China rich list, and the Bank of China. A separate study by US-based Bain & Company and China Merchants Bank in April of 2,600 high-net worth individuals - those who hold more than 10 million yuan (US$1.6 million) in individual investable assets (excluding primary residences and assets of poor liquidity) - found that about 60% of those interviewed had completed immigration applications to other countries or had plans to do so.

About 14% of the rich Chinese people, each of whom has a net asset of more than 60 million yuan, said they had either already moved overseas or applied to do so, according to the Hurun findings, which were based on one-on-one interviews with 980 rich Chinese people in 18 mainland cities from May to September.

Another 46% said they planned to emigrate within three years, variously citing higher-quality education available for their children overseas, better healthcare, concerns about the security of their assets on the mainland and hopes for a better life in retirement.

The most favorable destinations by rich Chinese is the US, with 40% of respondents claiming it was their first choice, followed by Canada and Singapore. Encouraging them in their quest, the United States continues to lower its threshold for businesspersons’ immigration.

Some 70% of the 4,218 visas issued under the US Immigrant Investor Program, known as EB-5 visas, issued in 2009 were applicants from China, data from the US Department of State show. In 2010, more than 70,000 Chinese applicants obtained permanent residency in the US, accounting for 7% of total applicants, placing second behind only Mexican applicants, according to the US Department of Homeland Security.

Canada allocated more than 1,000 of its targeted 2,055 immigrant investors to Chinese people in 2009 and last year, 2,020 Chinese applicants obtained permanent residency in Canada through investment, accounting for 62.6% of the total immigrant investors to Canada, data from Citizenship and Immigration Canada showed.

Kathy Cheng, an investment immigration consultant based in Shenzhen, next to Hong Kong, attributed the popularity of the US to it not having a cap on its investment visa program. The minimum amount required for investment immigration to the US is $500,000, and among all destinations that offer investment immigration, the US is alone in not imposing a quota.

“Recently, the US is trying to overhaul the immigration laws to attract rich or high-skilled foreigners. The moves have attracted the attention of some wealthy Chinese, who can afford to live elsewhere," she said to Asia Times Online by telephone.

Two US senators, Democratic Chuck Schumer and Republican Mike Lee, last month introduced a bill that would give residence visas to foreigners who spend at least US$500,000 to buy houses in the country. The proposal would allow foreigners immigrating to the United States to bring a spouse and any children under the age of 18. The provision would create visas that are separate from current programs so as to not displace anyone waiting for other visas.

The US Ambassador to China, Gary Locke, the former US commerce secretary who took on his latest post in August, said the US will make its investment and commercial environment as open and appealing as possible to increase Chinese investment in the US to create more jobs for Americans, which is the foremost priority of the Barack Obama administration.

"We will help Chinese companies and entrepreneurs better understand the benefits and ease of investing in the US by establishing factories, facilities, operations and offices," Locke told US business leaders in Beijing in September.

In May, President Obama said the US needs to overhaul its immigration laws to secure high-tech foreign talent to address a shortages of scientists and experts in the high-technology sector. In the same month, the Obama administration extended the Optional Practical Training program to allow students graduating in fields that include soil microbiology, pharmaceuticals and medical informatics, to be able to find a job or work in the US for up to 29 months (instead of 12) after graduation.

New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg said recently at a Council on Foreign Relations event in Washington, that to spur job growth, the US should allow foreign graduates from US universities to obtain green cards (permanent residency), ending caps on visas for highly skilled workers, and setting green-card limits based on the country's economic needs not an immigrant's family ties.

Of the 980 people interviewed by Hurun Report and the BOC, about 35% said they have assets overseas, which on an average accounted for 19% of their total assets; 32% of those surveyed said they have invested overseas with a view to emigrate and half said they did so mainly for the sake of their children's education.

A mainlander who has manganese mines in his home province of Guangxi said he was applying to emigrate to Canada from his home region in southeast Guangxi, mainly due to take advantage of better education overseas for his two-year-old son.

"An increasing number of parents in China prefer their children to receive education overseas instead of with the examination-oriented education system in China," said the mine owner, who asked not to be identified.

However, a source close to him said the mine owner had assets worth millions of dollars and "underground" businesses; given changeable government policies, emigration was the best way of protecting some of this wealth.

"Despite Beijing's currency rules, the wealthy have many ways to move their money out of the country. Besides, part of his money comes from smuggling, though his business is far smaller than Lai Changxing," said the source.

Lai Changxing was extradited to China from Canada in July after a 12-year exile there. He is expected to face charges for smuggling to a value of US$10 billion, bribery and tax evasion.

Under Beijing's capital rules, anyone leaving China can carry with them a maximum of 20,000 yuan (US$3,100) or the equivalent of US$5,000 in foreign currency. However, it is commonly known that wealthy Chinese are free to leave the country with briefcases full of cash.

Ye Tan, an independent economist and commentator in Beijing, said the growing gap between the rich and the poor in the mainland, which has aroused discontent among the less well off, has made some of the wealthy feel uncomfortable.

"The lack of security sense about the safety of their assets among Chinese wealthy is like a huge black cloud hanging over their heads," Ye was quoted as saying in the Hurun survey report.

China has 960,000 "yuan millionaires" with personal wealth of 10 million yuan (US$1.5 million) or more, according to the GroupM Knowledge - Hurun Wealth Report 2011. The figure is up 9.7% from a year earlier. China has 60,000 "super rich' with 100 million yuan or more, up 9% on a year earlier.

Average monthly income in China is only about 2,000 yuan, despite double-digit economic growth for about the past three decades.

China's Gini coefficient, a commonly used measure of wealth inequality, reached 0.47 in China last year, according to the National Development and Reform Commission, above the international warning level of 0.4, which is considered to be the level that could trigger social unrest.