'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label free speech. Show all posts

Showing posts with label free speech. Show all posts

Sunday, 16 June 2024

Wednesday, 24 January 2024

Saturday, 5 December 2020

Mandated ‘respect’ for others’ opinions hurts free speech

A polite but deadly serious Cambridge university row over the issue shows the need for ‘tolerance’ instead writes CAMILLA CAVENDISH in The FT

If you wander down Trumpington Street in Cambridge, you will find yourself at one of the birthplaces of the English Reformation. It was here, at The White Horse Inn, that scholars secretly met to debate the smuggled works of Martin Luther. By preaching Luther’s heretical belief that ordinary people should read the Bible for themselves, and not just accept the word of priests, Cambridge was one of the places that helped to transform European thought. So it is especially sad that the University of Cambridge is now pushing proposals which could undermine free speech.

If you wander down Trumpington Street in Cambridge, you will find yourself at one of the birthplaces of the English Reformation. It was here, at The White Horse Inn, that scholars secretly met to debate the smuggled works of Martin Luther. By preaching Luther’s heretical belief that ordinary people should read the Bible for themselves, and not just accept the word of priests, Cambridge was one of the places that helped to transform European thought. So it is especially sad that the University of Cambridge is now pushing proposals which could undermine free speech.

The university’s governing body, the Regent House, is voting until Tuesday on a new code of conduct which demands that staff, students and visitors be “respectful” of different opinions. This harmless-sounding clause is meant to support free speech. It was drawn up partly in response to faculty who were alarmed after a student backlash led to the rescinding of a fellowship to the psychologist Jordan Peterson, a self-styled “professor against political correctness”. But the row also demonstrates how dangerous it can be when well-meaning people try to please everyone. “Respect” is a soft-edged word that means different things to different people. It can easily morph into a prohibition against giving offence.

“There’s no limit to how far this could go,” I was told by Arif Ahmed, the young philosopher at Gonville and Caius college who is leading a rebellion of academics against the code. “Did the Charlie Hebdo cartoons respect Islam? Was [18th-century Scottish philosopher] David Hume a respecter of religion? Who decides? A word like ‘respect’ is worse than useless. You can slide all the way from civility to a kind of deference which would refrain from attacking Islam, Christianity or Judaism.”

The new code defends “robust and challenging” debate, and “free speech within the law”. However, it seems to undermine those clauses with the demand that staff, students and visitors be “free to express themselves without fear of disrespect or discrimination”.

The problem is that there is no limit to what any individual might define as disrespect. Furthermore, while all beliefs should get a hearing they cannot, as Stephen Fry has said, command the heart. That is why Oxford university’s concise policy on free speech says that not all theories deserve equal respect. Cambridge’s proposal threatens the lifeblood of academic progress: the right to argue, challenge and, potentially, change minds.

Strangely, Cambridge’s authorities seem unable to see the problem. Over the summer, concerned academics asked its executive body, the Council, if it would replace the word “respect” with “tolerance”. This would promote courtesy but ensure that people could openly disagree. The Council refused. At that point, a polite but deadly serious war broke out. A growing number of academics now support amendments to the proposed policy, including philosopher Simon Blackburn, economist Diane Coyle and statistician Sir David Spiegelhalter.

Mystified why the Council rejected the seemingly helpful “tolerance” proposal, I asked the university’s vice-chancellor, Stephen Toope. He doesn’t remember the rebels’ proposal being “so clearly articulated at the time”. He told me, robustly, that “free speech is utterly central, and if we don’t uphold it we’re not doing our job”. He also warned against “overinterpreting what is meant to be a very high level statement”. Professor Toope has chaired meetings with the neutrality expected of his role. “I am not taking a position on ‘respect’ or ‘tolerance’,” he said, “though I have heard some people say they don’t like the word ‘tolerance’ as it makes it seem as if other views are to be discredited.”

This, surely, goes to the heart of the issue. Tolerance is an ancient concept, and the best protector of free speech when people strongly disagree with each other: it allows issues to be aired and weaknesses exposed. I happen to deplore the pro-life movement. I have marched against it in the US and donated to pro-choice campaigns. But I defend pro-lifers’ right to make their case. I also note that pro-life charities have become vociferous in favour of free speech, along with some Jewish and feminist groups. Proponents of unfashionable causes often discover the importance of freedom of expression, which underlines its value.

The Cambridge row shows how hard it is for institutions to keep their footing in this new world of outrage. Twenty years ago, English universities felt little responsibility towards students beyond the lecture hall. Today, they are beset by activism, and demands for censorship from the political left and right.

The way to navigate these choppy waters is surely with the rigour and precision that characterise the best academic work. The vagueness of language in Cambridge’s new code lacks both. Some academics worry that it will have a chilling effect on who they invite and what they say, and that this may extend to their own contracts. “If the respect agenda becomes entrenched in disciplinary and grievance procedures, and arguments which used to be sorted out by people saying ‘grow up and stop being silly’ fall to intervention by HR busybodies, that will mean the end of academic tenure as we know it,” Ross Anderson, Cambridge Professor of Security Engineering, told me.

Such fears may be exaggerated. But the code’s fudge is dangerous. Do we really want to risk returning to a world where enquiring minds huddle together in secret, debating banned works and wondering if they dare say what they believe? If universities don’t do everything in their power to prevent such a reversal, they are not worthy of the title.

Tuesday, 3 February 2015

Tuesday, 13 January 2015

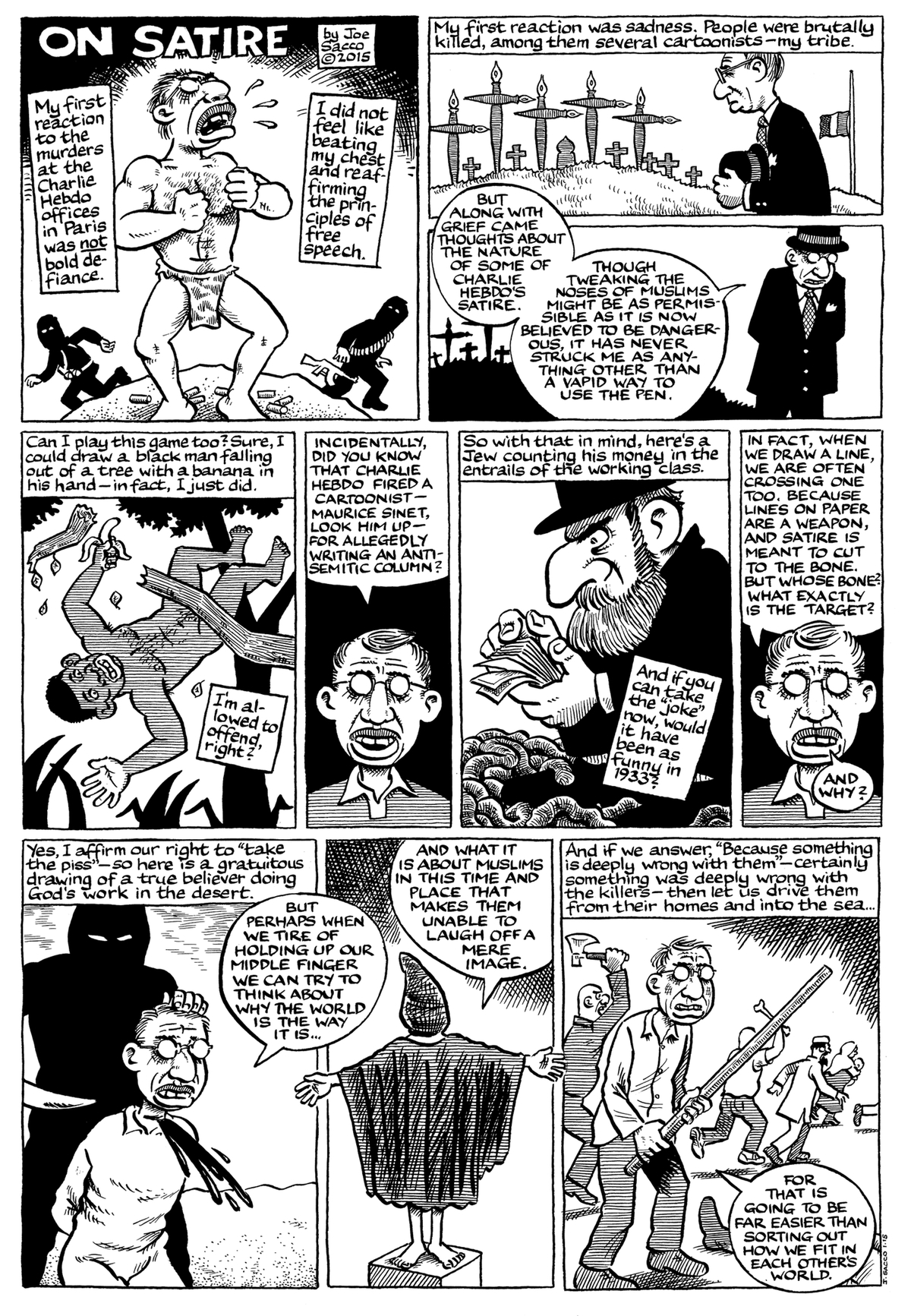

Speaking power to satirical truth

Rajgopal Saikumar in The Hindu

A joke or laughter from a position of superiority over other people is unworthy of moral support, although it may obtain legal protection

Charlie Hebdo was brutally attacked for its dark sketches of humour; for apparently talking ‘satire to power.’ French President Francois Hollande called the attacks an assault on “the expression of freedom,” and liberal democracies globally have shown their support to protectthis freedom. Cartoonists in solidarity with Charlie Hebdo sketched the incongruity of a pencil and a gun. But what explains this incongruity? What is it about satirical humour that can invite such anger or can justify its protection, even through so-called “legitimate” state violence?

Novelist Salman Rushdie, a victim/perpetrator of such violence, calls this “art of satire” a “force of liberty against tyranny.” Spanish painter Francisco Goya was at odds with Fernando VII for the cartoons that he sketched, and it was Honore Daumier’s caricatures of King Louise-Philippe and the French legislature that landed him in prison. Before I continue, here are two disclaimers: first, interrogating the value of humour or satire does not in any way imply justifying the attack and the killings, for these are separate categories. Second, several of the anti-Islamic cartoons of Charlie Hebdo are not really ‘satires’ in the strict sense, for they seem to lack the complexity and the nuances implicit in the genre.

A shared world

Understanding a joke presupposes a common social world; a shared intersubjective community. There need not be an agreement about the worth of the joke itself, but it presupposes the fact that a sense of humour requires a shared lifeworld and not an individualistic, solipsistic and atomised world. Humour is, therefore, highly local; it throws light on our situation, it tells us something about who we are, it brings back to consciousness the hidden and it familiarises the unspoken. Umberto Eco wrote an illuminating essay on something as trivial as eating peas with a fork in airline food — transforming the real and everyday into something surreal and unfamiliar. R.K. Laxman’s political cartoons, ‘The Common Man,’ used domestic, everyday images of a middle-class family to challenge mainstream politics. Although he mounts a successful challenge to politics, his portrayals of domesticity unknowingly reveal gendered relations within Indian homes, for instance, between the husband and wife. In a similar analogy, as the Marxist commentator Richard Seymour suggests, Charlie Hebdo may be mocking the extremists, but that mocking itself reveals a certain racist undertone.

The mechanism of humour, caricatures and satires is to distance us from the local and the familiar and transform it to the unfamiliar. This “distancing” helps us to better see the absurdity in our social conditions. English philosopher Simon Critchley uses religious metaphors to suggest that laughter has a “messianic” and a “redemptive power” because it can reveal a situation and also indicate how it might have changed. But the flip side of jokes and satires being highly context-specific and localised is that humour can often also be parochial, ridiculing outsiders and foreigners. Watching “Monty Python” now, three decades since it was made, I realise the parochial stereotyping that the film indulges in.

Is humour and this “art of satire” — in itself and inherently — worthy of protection as several are claiming it to be? Not necessarily. A joke or laughter from a position of superiority over other people considered inferior is unworthy of moral support, although it may obtain legal protection. The philosopher Jason Stanley pointed out that there is a difference in France between mocking the Pope and mocking Prophet Muhammad. “The Pope is the representative of the dominant traditional religion of the majority of French citizens. Prophet Muhammad is the revered figure of an oppressed minority. To mock the Pope is to thumb one’s nose at a genuine authority, an authority of majority. To mock Prophet Muhammad is to add insult to abuse.” This argument by Mr. Stanley is an instance of humour where the power relation is already precarious — embedded in a culture of white, Western supremacy. So the cartoon may not be speaking resistance to power, but may itself be embodied in power, ridiculing the powerless.

To be clear, India’s External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj and Prime Minister Narendra Modi may show their support to France, but the Indian legal framework would most likely never tolerate such cartoons. Be it the Hicklin test in Ranjit Udeshi (1964) or the Community Standards test in Aveek Sarkar (2014), there is little doubt that the images would be held obscene under Section 292 of the Indian Penal Code by the Supreme Court (“…a book, pamphlet, paper, writing, drawing, painting, representation, figure or any other object, shall be deemed to be obscene if it is lascivious or appeals to the prurient interest or if its effect…”). The threat of public disorder is etched deep in our judicial psyche, and the probability that Charlie Hebdo-styled art would receive protections under Article 19 of the Constitution (freedom of expression) is almost close to impossible. Does that mean India is less of a liberal democracy by doing this? The debate is fast becoming a “liberal democracy” versus “religious extremism” rupture, but it is not clear whether liberty has such a clear moral victory over these offended subjects of humour.

There is absolutely no justification for the brutal attacks on Charlie Hebdo, and solidarity with the publication is unconditional. The attempt here is to merely nuance the debates on the second aspect of this issue: the rhetoric of liberal, democratic free speech.

The notion of “power” is being ignored in our thinking about free speech in liberal democracies. Liberalism may encourage liberty and autonomy in speech and expression, but we are not abstract individuals freely expressing our thoughts in an ideal society. We are thrown into a shared and coexistent world where power relations obscure the suspicious neatness of liberalism.

Wednesday, 10 July 2013

How can India give asylum to a person chased by the almighty US when it panics over giving a residence permit to a secular writer?

'I’m Not Surprised India Refused Snowden Asylum'

TASLIMA NASREEN

I came to India not as a rebel Bangladeshi writer, but as a European citizen. I eagerly chose India’s state of West Bengal as my new home. But when I was physically attacked by Muslim fundamentalists, instead of taking action against them, the government kept me under house arrest. Not only that, I was repeatedly asked to leave the state and, preferably, the country. When a group of Muslim fundamentalists organised a protest against my stay in India, I was thrown out of Bengal, the state that had been my home for years. Finally, the central government took charge and put me in a safehouse. But there was pressure from the Centre too for me to leave the country. Now, I am given permission to live in India, but only in Delhi. My enemies are just a handful of corrupt, illiterate, ignorant Muslim fundamentalists but yet India cannot challenge them.

TASLIMA NASREEN

Edward Snowden asked 21 nations for political asylum. He got nothing but rejection, proving once again that free speech is just a decorative item for most governments. India’s embassy in Moscow received Snowden’s request for asylum. His request was rejected within hours.

Since then, there has been much discussion about India’s generosity over giving shelter to persecuted people—and so then, why not Snowden? India has in the past granted political asylum to Dalai Lama and many other rebels. Some even mention my name in the list.

I am not sure whether I should be considered a political refugee in India. I was thrown out of my country, Bangladesh, in 1994 and found myself landing in Europe. It was difficult for me to live in a place which has a totally different climate and culture from where I grew up. Since I knew I couldn’t return to my country, I wanted to come to India. But India kept her doors firmly shut. Towards the end of 1999, I was given permission to visit as a tourist.

|

I’m not surprised India refused Snowden asylum. How can a country give asylum to a person chased by the almighty US when it panics over giving a residence permit to a secular writer? But with India, one understands; it can’t afford to take risks or make any big political mistake now. Indeed, a European country should have given Snowden asylum. They have a long tradition of defending writers and journalists. Compared to India, they have a much older, truer democracies, and violation of rights and free speech is a rarity there. It’s time for Europe to show they are not mere colonies of the US. However glorious a past India may have had, it doesn’t have the courage to face possible US sanctions. If democracy were practised everywhere, and if it were not reduced to mere elections, independent voices from independent countries would have been respected. As it stands, the human species is yet to make the world an evenly civilised place. We ordinary people pay the brunt, we sacrifice our dignity, honor, rights and freedom. I really feel sorry for Snowden. If I were a country, I’d have given him asylum.

Bangladesh-born Taslima Nasrin is the author of Lajja and other novels; E-mail your columnist: letters AT outlookindia.com

Friday, 17 August 2012

Ecuador's brave decision to provide asylum to Assange

This is what is called courage. This is the power of conviction. Even as the big bullies of global politics – US & UK – were trying to arm-twist Rafael Correa, the president of Ecuador, into submission, the South American leader showed how bold he was by giving asylum to Julian Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks who has changed the nature of journalism and the way the governments do their business – their dirty business.

Correa is a man of conviction. He has battled Ecuador’s robber barons – always backed by the US -- and the right-wing media on his way to the country’s presidency. He represents that generation of South America's left-wing leaders who decline to give in to American pressure and refuse to be treated as America’s backyard.

In his interview with Julian Assange on his show on Russia Today (RT) television channel a few months ago, Correa was clear about what he thought of Washington. When Julian Assange asked him what do “the Ecuadorean people think about the US and its involvement in Latin America and in Ecuador?” Correa said: “Evo Morales (the Bolivian president) says, the ‘only country that can be sure never to have a coup d’etat is the United States because it hasn’t got a U.S. Embassy’.” Spot on!

Then he spoke about how the Americans funded and controlled the police in Ecuador – and hence its economy and politics. After coming to power, Correa cut that money trail, and that led to some anger in police units. “I’d like to say that one of the reasons that led to police discontent was the fact that we cut all the funding the U.S. Embassy provided to the police. Before and even after we took office, we took a while to correct this. Before, there were whole all police units, key units, fully funded by the U.S. Embassy whose offices in command were chosen by the U.S. ambassador and paid by the U.S. And so we have increased considerably the police pay…”

The Julian Assange Show – one of the best shows on television ever – was an eye opener. Even after Assange walked into the Ecuadorean embassy and stopped doing the show, RT continued following the story, though the WikiLeaks founder almost vanished from the screens of BBC and CNN. I have been following the Assange’s asylum drama on RT for months and now it’s clear to me what the western governments are really afraid of. Speaking on the channel in an interview on Wednesday, Steve Wozniak, who co-founded Apple Computers with Steve Jobs in 1976, said, “As far as WikiLeaks, I wish I knew more about the whole case. On the surface it sounds to me like something that’s good. The whistleblower blew the truth. The people found out what they the people had paid for. And the government says, ‘No, no, no. The people should not know what the people had paid for.”

Another big revelation came from Kevin Zeese, who has been running a campaign for Bradley Manning, the US army private who presumably leaked all the cables to Assange and is now rotting in a US prison. Speaking on RT, Zeese said the US calls Assange a “high-tech terrorist” because the “US is scared by the information disseminated by Assange, as it reveals corruption at all levels of the US government.”

“There is an embarrassment to the US Empire, but no one has been killed by this. There has been no undermining of US national security,” said Kevin Zeese, emphasizing that what really worries the government is that the public sees what the US does on a “day-to-day basis.”

Zeese is not the only one exposing the truth behind Britain’s “veiled threats” to storm the Ecuadorean embassy in London and hand over Assange to Sweden. The British call it their “binding obligation.” But their intention is highly suspicious. According to David Swanson, an author and activist, it is likely that if Assange was extradited to Sweden he would handed over to the US where he will be tried for espionage, given “the unusualness of the extradition with no charges in place.”

The threat to Assange’s freedom is real. According to an email from US-based intelligence company, Stratfor, leaked in February, US prosecutors had already issued a secret indictment against Assange. “Not for Pub. — We have a sealed indictment on Assange. Pls protect,” Stratfor official Fred Burton wrote in a January 26, 2011, email obtained by hacktivist group Anonymous.

Now, the question is if Assange can get out of the Ecuadorean embassy in London, get to the Heathrow and take a flight to Ecuador. It’s not easy. The British – in complete violation of international law – might arrest him the moment he steps out of the building. The Americans – in complete violation of international law – can scramble their fighter jets and force his plane to land in Guantanamo. They have already declared him a terrorist (That also makes terrorists of all journalists and newspapers who wrote and carried reports based on the leaked cables).

Taking out innocent people in the name of “war on terror” is America’s new business. Believe it or not, US President Barack Obama, the Nobel peace prize winner, personally has been signing death warrants for “terrorists”, who quite often turn out to be ordinary villagers, farmers, school children and women in the dusty valleys of Afghanistan. This is Dronophilia – killing people with a remote control, with a pilotless machine hovering over, with a missile that blows people to bits, and they don’t need to confirm if they got their ‘target’.

Ecuador has done the right thing by giving asylum to Assange. A small country has stood up to the big bullies of global politics even when the so-called giants of the new global order – India and China – have remained mute spectators to the whole drama. They have failed to speak for free speech, human rights and transparency in government affairs.

Julian Assange exposed the crimes and dirty games the big powers play. So, they went after him. Now, Ecuador has given him shelter. They will for sure go after this small country now, for sure. This will be a good excuse to meddle into the internal affairs of South American again.

Ecuador has done a brave thing but now it needs to be careful. It needs to be very careful. The whole South American continent needs to be careful now…

Correa is a man of conviction. He has battled Ecuador’s robber barons – always backed by the US -- and the right-wing media on his way to the country’s presidency. He represents that generation of South America's left-wing leaders who decline to give in to American pressure and refuse to be treated as America’s backyard.

In his interview with Julian Assange on his show on Russia Today (RT) television channel a few months ago, Correa was clear about what he thought of Washington. When Julian Assange asked him what do “the Ecuadorean people think about the US and its involvement in Latin America and in Ecuador?” Correa said: “Evo Morales (the Bolivian president) says, the ‘only country that can be sure never to have a coup d’etat is the United States because it hasn’t got a U.S. Embassy’.” Spot on!

Then he spoke about how the Americans funded and controlled the police in Ecuador – and hence its economy and politics. After coming to power, Correa cut that money trail, and that led to some anger in police units. “I’d like to say that one of the reasons that led to police discontent was the fact that we cut all the funding the U.S. Embassy provided to the police. Before and even after we took office, we took a while to correct this. Before, there were whole all police units, key units, fully funded by the U.S. Embassy whose offices in command were chosen by the U.S. ambassador and paid by the U.S. And so we have increased considerably the police pay…”

The Julian Assange Show – one of the best shows on television ever – was an eye opener. Even after Assange walked into the Ecuadorean embassy and stopped doing the show, RT continued following the story, though the WikiLeaks founder almost vanished from the screens of BBC and CNN. I have been following the Assange’s asylum drama on RT for months and now it’s clear to me what the western governments are really afraid of. Speaking on the channel in an interview on Wednesday, Steve Wozniak, who co-founded Apple Computers with Steve Jobs in 1976, said, “As far as WikiLeaks, I wish I knew more about the whole case. On the surface it sounds to me like something that’s good. The whistleblower blew the truth. The people found out what they the people had paid for. And the government says, ‘No, no, no. The people should not know what the people had paid for.”

Another big revelation came from Kevin Zeese, who has been running a campaign for Bradley Manning, the US army private who presumably leaked all the cables to Assange and is now rotting in a US prison. Speaking on RT, Zeese said the US calls Assange a “high-tech terrorist” because the “US is scared by the information disseminated by Assange, as it reveals corruption at all levels of the US government.”

“There is an embarrassment to the US Empire, but no one has been killed by this. There has been no undermining of US national security,” said Kevin Zeese, emphasizing that what really worries the government is that the public sees what the US does on a “day-to-day basis.”

Zeese is not the only one exposing the truth behind Britain’s “veiled threats” to storm the Ecuadorean embassy in London and hand over Assange to Sweden. The British call it their “binding obligation.” But their intention is highly suspicious. According to David Swanson, an author and activist, it is likely that if Assange was extradited to Sweden he would handed over to the US where he will be tried for espionage, given “the unusualness of the extradition with no charges in place.”

The threat to Assange’s freedom is real. According to an email from US-based intelligence company, Stratfor, leaked in February, US prosecutors had already issued a secret indictment against Assange. “Not for Pub. — We have a sealed indictment on Assange. Pls protect,” Stratfor official Fred Burton wrote in a January 26, 2011, email obtained by hacktivist group Anonymous.

Now, the question is if Assange can get out of the Ecuadorean embassy in London, get to the Heathrow and take a flight to Ecuador. It’s not easy. The British – in complete violation of international law – might arrest him the moment he steps out of the building. The Americans – in complete violation of international law – can scramble their fighter jets and force his plane to land in Guantanamo. They have already declared him a terrorist (That also makes terrorists of all journalists and newspapers who wrote and carried reports based on the leaked cables).

Taking out innocent people in the name of “war on terror” is America’s new business. Believe it or not, US President Barack Obama, the Nobel peace prize winner, personally has been signing death warrants for “terrorists”, who quite often turn out to be ordinary villagers, farmers, school children and women in the dusty valleys of Afghanistan. This is Dronophilia – killing people with a remote control, with a pilotless machine hovering over, with a missile that blows people to bits, and they don’t need to confirm if they got their ‘target’.

Ecuador has done the right thing by giving asylum to Assange. A small country has stood up to the big bullies of global politics even when the so-called giants of the new global order – India and China – have remained mute spectators to the whole drama. They have failed to speak for free speech, human rights and transparency in government affairs.

Julian Assange exposed the crimes and dirty games the big powers play. So, they went after him. Now, Ecuador has given him shelter. They will for sure go after this small country now, for sure. This will be a good excuse to meddle into the internal affairs of South American again.

Ecuador has done a brave thing but now it needs to be careful. It needs to be very careful. The whole South American continent needs to be careful now…

Friday, 25 May 2012

If there were global justice, Nato would be in the dock over Libya

Liberia's Charles Taylor has been convicted of war crimes, so why not the western leaders who escalated Libya's killing?

Illustration by Belle Mellor

Libya was supposed to be different. The lessons of Iraq and Afghanistan had been learned, David Cameron and Nicolas Sarkozy insisted last year. This would be a real humanitarian intervention. Unlike Iraq, there would be no boots on the ground. Unlike in Afghanistan, Nato air power would be used to support a fight for freedom and prevent a massacre. Unlike the Kosovo campaign, there would be no indiscriminate cluster bombs: only precision weapons would be used. This would be a war to save civilian lives.

Seven months on from Muammar Gaddafi's butchering in the ruins of Sirte, the fruits of liberal intervention in Libya are now cruelly clear, and documented by the UN and human rights groups: 8,000 prisoners held without trial, rampant torture and routine deaths in detention, the ethnic cleansing of Tawerga, a town of 30,000 mainly black Libyans (already in the frame as a crime against humanity) and continuing violent persecution of sub-Saharan Africans across the country.

A year after the western powers tried to make up for lost ground in the Arab uprisings by tipping the balance of the Benghazi-led revolt, Libya is in the lawless grip of rival warlords and armed conflict between militias, as the western-installed National Transitional Council (NTC) passes Gaddafi-style laws clamping down on freedom of speech, gives legal immunity to former rebels and disqualifies election candidates critical of the new order. These are the political forces Nato played the decisive role in bringing to power.

Now the evidence is starting to build up of what Nato's laser-guided bombing campaign actually meant on the ground. The New York-based Human Rights Watch this week released a report into the deaths of at least 72 Libyan civilians, a third of them children, killed in eight separate bombing raids (seven on non-military targets) – and denounced Nato for still refusing to investigate or even acknowledge civilian deaths that were always denied at the time.

Given the tens of thousands of civilians killed by US, British and other Nato forces both from the air and on the ground in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Yemen over the last decade, perhaps Nato commanders prefer not to detain themselves with such comparative trifles. And Human Rights Watch believes that, whatever the real number of civilians directly killed by Nato bombing, it was relatively low given the 10,000-odd sorties flown.

But while Nato's UN mandate was to protect civilians, the alliance in practice turned that mission on its head. Throwing its weight behind one side in a civil war to oust Gaddafi's regime, it became the air force for the rebel militias on the ground. So while the death toll was perhaps between 1,000 and 2,000 when Nato intervened in March, by October it was estimated by the NTC to be 30,000 – including thousands of civilians.

We can't of course know what would have happened without Nato's bombing campaign, even if there is no evidence that Gaddafi had either the intention or capability to carry out a massacre in Benghazi. But we do know that Nato provided decisive air cover for the rebels as they matched Gaddafi's forces war crime for war crime, carried out massacres of their own and indiscriminately shelled civilian areas with devastating results – such as reduced much of Sirte to rubble last October.

There were also Nato and Qatari boots on the ground, including British special forces, co-ordinating rebel operations. So Nato certainly shared responsibility for the deaths of many more civilian than its missiles directly incinerated.

That is the kind of indirect culpability that led to the conviction last month of Charles Taylor, the former president of Liberia, in the UN-backed special court for Sierra Leone in The Hague. Taylor, now awaiting sentence and expected to be jailed in Britain, was found guilty of "aiding and abetting" war crimes and crimes against humanity during Sierra Leone's civil war in the 1990s. But he was cleared of directly ordering atrocities carried out by Sierra Leonean rebels.

Which pretty well describes the role played by Nato in Libya last year. International lawyers say legal culpability would depend on the degree of assistance and knowledge of war crimes for which Nato provided cover, even if the political and moral responsibility could not be clearer.

But there is of course simply no question of Nato leaders being held to legal account for the Libyan carnage, any more than they have been for far more direct crimes carried out in Iraq and Afghanistan. The only Briton convicted of a war crime over the bloodbath of Iraq has been Corporal Donald Payne, for abuse of prisoners in Basra in 2003. While George Bush has boasted of authorising the international crime of torture and faced not so much as a caution.

Which only underlines that what is called international law simply doesn't apply to the big powers or their political leaders. In the 10 years of its existence, the International criminal court has indicted 28 people from seven countries for war crimes and crimes against humanity. Every single one of them is African – even though ICC signatories include war-wracked states such as Colombia and Afghanistan.

That's rather as if the criminal law in Britain only applied to people earning the minimum wage and living in Cornwall. But so long as international law is only used against small or weak states in the developing world, it won't be a system of international justice, but an instrument of power politics and imperial enforcement.

Just as the urgent lesson of Libya – for the rest of the Arab world and beyond – is that however it is dressed up, foreign military intervention isn't a short cut to freedom. And far from saving lives, again and again it has escalated slaughter.

Thursday, 15 March 2012

Cambridge student gets seven-term ban for poetic protest at Willetts speech

Sentence against PhD student imposed by the university's court of discipline condemned as 'the height of hypocrisy'

-

Jeevan Vasagar, education editor

- guardian.co.uk,

Higher education minister David Willetts

was told 'your gods have failed' in the protest at Cambridge University.

Photograph: Anna Gordon for the Guardian

A PhD student at Cambridge University has been suspended until the end of 2014 for his role in a protest against the higher education minister, David Willetts.

In a ruling condemned as a travesty by fellow students, the English literature student was suspended for seven terms after reading out a poem that disrupted a speech by the minister.

The student, named by a student newspaper as Owen Holland, read out a poem that included the lines: "You are a man who believes in the market and in the power of competition to drive up quality. But look to the world around you: your gods have failed."

The minister was forced to abandon the speech on the "Idea of a University" last November, as protesters repeated the lines of the poem in response to the student.

The sentence – known as rusticating – was imposed by the university's court of discipline, an independent body presided over by a high court judge.

In response, more than 60 academics and students wrote a "Spartacus" letter to the university admitting to their role in the original protest and demanding that they be charged for the same offence.

Rees Arnott-Davies, a student at Corpus Christi college, who was among the protesters, said: "This is out of all proportion. Two and a half years for an entirely legal and peaceful protest is an absolute travesty and makes me ashamed to study at this university. The idea that you can protect freedom of speech by silencing protest is the height of hypocrisy."

Arnott-Davies said the court had exceeded the punishment requested by the university's legal counsel, which sought a one-term suspension.

A Cambridge University spokesman said: "The university notes the decision of the court of discipline in its proceedings. By statute, the court of discipline is an independent body, which is empowered to adjudicate when a student is charged with an offence against the discipline of the university by the university advocate. The court may impose a range of sentences as defined by the statute."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)