'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label satire. Show all posts

Showing posts with label satire. Show all posts

Wednesday, 21 February 2024

Sunday, 26 June 2022

Sunday, 29 August 2021

Tuesday, 3 February 2015

Saturday, 17 January 2015

What a perfect tribute to satire the Paris march turned out to be

Mark Steel in The Independent

To start with, we should

congratulate the Prime Minister of Israel

and ambassador for Saudi

Arabia

Across Gaza

And Raif Badawi will

appreciate the Saudi government’s presence on a day for free speech, because

he’s been sentenced to one thousand lashes by the Saudi government for setting

up a liberal website. They must be lashing him for not being critical enough I

suppose.

If the Saudis were really

imaginative they could have taken Badawi to Paris

Or it’s possible the famous

phrase that, “I don’t like what you say but will defend your right to say it,”

gets lost in translation to the Arabic, and comes out as, “I may disagree with

what you say, in which case I’ll strap you to a stick and rip your skin off”.

Presumably the judge said to him: “Your website shouldn’t just be liberal, it

should show cartoons of the King riding around on a pig at the very least. Take

off your shirt.”

It was also cheery to see

Sergei Lavrov, Putin’s foreign minister, having a giggle by showing up. Because

the first thing you think whenever you see Putin is how much he loves it when

journalists take the piss out of him.

“Make my nose more grotesque,

I’m not hideous enough,” he shouts at legions of cartoonists employed to mock

him. And he was genuinely angered by the shootings in Paris

Alongside the Russian was

Sameh Shoukry, foreign minister for Egypt

Because everyone agrees it’s

essential to allow things to be broadcast, even if we don’t like them.

Newspapers such as The Sun and the Daily Mail have been especially passionate

about this issue, which must explain why they’ve never criticised the BBC or

Channel 4 for showing anything too sexual; or with swearing; or critical of the

Royal Family.

They were particularly

animated a few years ago after Russell Brand’s unpleasant prank with an

answerphone. I don’t recall what they said exactly, but presumably it must have

been: “We may not agree with it, but we defend to the death the right to

broadcast whatever message he left.”

Satire, The Sun has insisted

all week, is an essential part of our democracy because it mocks the powerful.

That’s why they’ve always taken the side of the common person, and happily sent

up important figures, such as newspaper owners, as in that biting sketch where

the head of a media empire suddenly forgets everything he’s ever done when he’s

in front of a phone-hacking inquiry.

“It’s essential to allow

satire to puncture those in charge,” agree those in charge. So David Cameron

and the Mail would love it if an act at the Royal Variety performance did a

sketch called Benefits

Palace

They’re all resolute that any

religion should be able to take a joke, which it undoubtedly should. So now’s

the time to make a situation comedy called A History of the Vatican, in which

Jimmy Savile is elected Pope because he’s the best at covering up child abuse.

“A tour de force, simply delightful,” would be the review in The Times.

Similarly, during one spate

of bombing in Gaza

This is why there should only

be one regret about the choice of personnel to lead the march for peace and

freedom of speech. The ultimate satire would have been for the final speaker to

have been a representative from al-Qaeda. He could have come on as a surprise

guest and begun, “We sent the gunmen, but we thought we’d like to be here

anyway”, to rapturous applause, as everyone fell about laughing at the

wonderful satire of the absurdity on display.

And it would be easy to film

the whole show and put it out as a DVD – jihadists seem quite adept at

organising that side of things already.

Tuesday, 13 January 2015

Speaking power to satirical truth

Rajgopal Saikumar in The Hindu

A joke or laughter from a position of superiority over other people is unworthy of moral support, although it may obtain legal protection

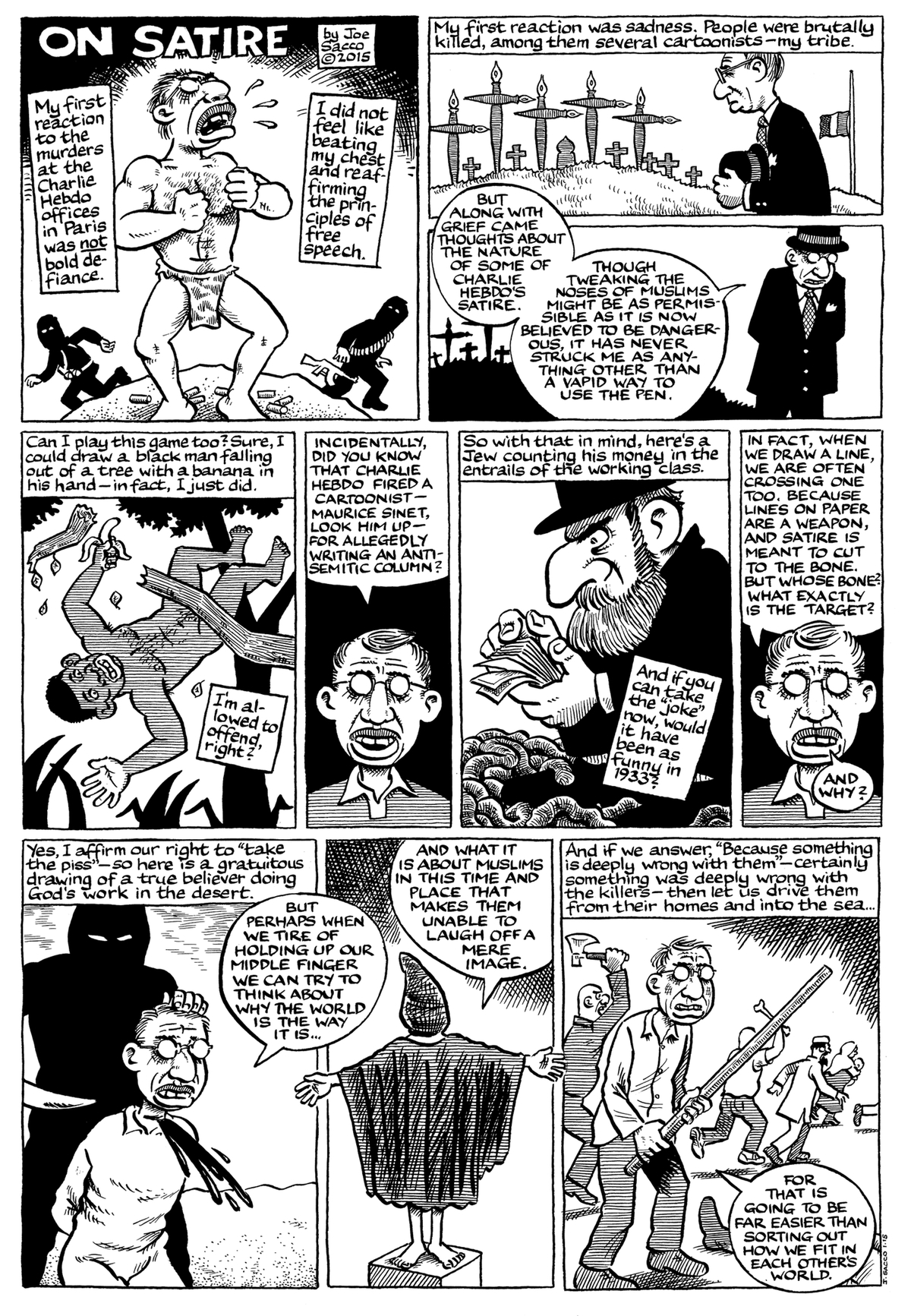

Charlie Hebdo was brutally attacked for its dark sketches of humour; for apparently talking ‘satire to power.’ French President Francois Hollande called the attacks an assault on “the expression of freedom,” and liberal democracies globally have shown their support to protectthis freedom. Cartoonists in solidarity with Charlie Hebdo sketched the incongruity of a pencil and a gun. But what explains this incongruity? What is it about satirical humour that can invite such anger or can justify its protection, even through so-called “legitimate” state violence?

Novelist Salman Rushdie, a victim/perpetrator of such violence, calls this “art of satire” a “force of liberty against tyranny.” Spanish painter Francisco Goya was at odds with Fernando VII for the cartoons that he sketched, and it was Honore Daumier’s caricatures of King Louise-Philippe and the French legislature that landed him in prison. Before I continue, here are two disclaimers: first, interrogating the value of humour or satire does not in any way imply justifying the attack and the killings, for these are separate categories. Second, several of the anti-Islamic cartoons of Charlie Hebdo are not really ‘satires’ in the strict sense, for they seem to lack the complexity and the nuances implicit in the genre.

A shared world

Understanding a joke presupposes a common social world; a shared intersubjective community. There need not be an agreement about the worth of the joke itself, but it presupposes the fact that a sense of humour requires a shared lifeworld and not an individualistic, solipsistic and atomised world. Humour is, therefore, highly local; it throws light on our situation, it tells us something about who we are, it brings back to consciousness the hidden and it familiarises the unspoken. Umberto Eco wrote an illuminating essay on something as trivial as eating peas with a fork in airline food — transforming the real and everyday into something surreal and unfamiliar. R.K. Laxman’s political cartoons, ‘The Common Man,’ used domestic, everyday images of a middle-class family to challenge mainstream politics. Although he mounts a successful challenge to politics, his portrayals of domesticity unknowingly reveal gendered relations within Indian homes, for instance, between the husband and wife. In a similar analogy, as the Marxist commentator Richard Seymour suggests, Charlie Hebdo may be mocking the extremists, but that mocking itself reveals a certain racist undertone.

The mechanism of humour, caricatures and satires is to distance us from the local and the familiar and transform it to the unfamiliar. This “distancing” helps us to better see the absurdity in our social conditions. English philosopher Simon Critchley uses religious metaphors to suggest that laughter has a “messianic” and a “redemptive power” because it can reveal a situation and also indicate how it might have changed. But the flip side of jokes and satires being highly context-specific and localised is that humour can often also be parochial, ridiculing outsiders and foreigners. Watching “Monty Python” now, three decades since it was made, I realise the parochial stereotyping that the film indulges in.

Is humour and this “art of satire” — in itself and inherently — worthy of protection as several are claiming it to be? Not necessarily. A joke or laughter from a position of superiority over other people considered inferior is unworthy of moral support, although it may obtain legal protection. The philosopher Jason Stanley pointed out that there is a difference in France between mocking the Pope and mocking Prophet Muhammad. “The Pope is the representative of the dominant traditional religion of the majority of French citizens. Prophet Muhammad is the revered figure of an oppressed minority. To mock the Pope is to thumb one’s nose at a genuine authority, an authority of majority. To mock Prophet Muhammad is to add insult to abuse.” This argument by Mr. Stanley is an instance of humour where the power relation is already precarious — embedded in a culture of white, Western supremacy. So the cartoon may not be speaking resistance to power, but may itself be embodied in power, ridiculing the powerless.

To be clear, India’s External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj and Prime Minister Narendra Modi may show their support to France, but the Indian legal framework would most likely never tolerate such cartoons. Be it the Hicklin test in Ranjit Udeshi (1964) or the Community Standards test in Aveek Sarkar (2014), there is little doubt that the images would be held obscene under Section 292 of the Indian Penal Code by the Supreme Court (“…a book, pamphlet, paper, writing, drawing, painting, representation, figure or any other object, shall be deemed to be obscene if it is lascivious or appeals to the prurient interest or if its effect…”). The threat of public disorder is etched deep in our judicial psyche, and the probability that Charlie Hebdo-styled art would receive protections under Article 19 of the Constitution (freedom of expression) is almost close to impossible. Does that mean India is less of a liberal democracy by doing this? The debate is fast becoming a “liberal democracy” versus “religious extremism” rupture, but it is not clear whether liberty has such a clear moral victory over these offended subjects of humour.

There is absolutely no justification for the brutal attacks on Charlie Hebdo, and solidarity with the publication is unconditional. The attempt here is to merely nuance the debates on the second aspect of this issue: the rhetoric of liberal, democratic free speech.

The notion of “power” is being ignored in our thinking about free speech in liberal democracies. Liberalism may encourage liberty and autonomy in speech and expression, but we are not abstract individuals freely expressing our thoughts in an ideal society. We are thrown into a shared and coexistent world where power relations obscure the suspicious neatness of liberalism.

Thursday, 11 July 2013

In praise of cynicism

It's claimed that at the age of 44 our cynicism starts to grow. But being cynical isn't necessarily a bad thing, argues Julian Baggini. It's at the heart of great satire and, perhaps more importantly, leads us to question what is wrong with the world – and strive to make it better

Test how cynical you are

Test how cynical you are

Bunch of cynics … Hislop, Brockovich, Bernstein, Snowden, Woodward and Tucker. Photograph: guardian.co.uk

If there's one thing that makes me cynical, it's optimists. They are just far too cynical about cynicism. If only they could see that cynics can be happy, constructive, even fun to hang out with, they might learn a thing or two.

Perhaps this is because I'm 44, which, according to a new survey, is the age at which cynicism starts to rise. But this survey itself merely illustrates the importance of being cynical. The cynic, after all, is inclined to question people's motives and assume that they are acting self-servingly unless proven otherwise. Which is just as well, as it turns out the "study" in question is just another bit of corporate PR to promote a brand whose pseudo-scientific stunt I won't reward by naming. Once again, cynicism proves its worth as one of our best defences against spin and manipulation.

I often feel that "cynical" is a term of abuse hurled at people who are judged to be insufficiently "positive" by those who believe that negativity is the real cause of almost all the world's ills. This allows them to breezily sweep aside sceptical doubts without having to go to the bother of checking if they are well-grounded. In this way, for example, Edward Snowden's leaks about the CIA's surveillance practices have been dismissed because they contribute to "the corrosive spread of cynicism".

In December 1999, Tony Blair hailed the hugely disappointing Millennium Dome as "a triumph of confidence over cynicism". All those legitimate concerns about the expense and vacuity of the end result were brushed off as examples of sheer, wilful negativity.

A more balanced definition of a cynic, courtesy of the trusty Oxford English Dictionary, is someone who is "distrustful or incredulous of human goodness and sincerity", sceptical of human merit, often mocking or sarcastic. Now what's not to love about that?

Of course, cynicism is neither wholly good nor bad. It's easy to see how you can be too cynical, but it's also possible to be not cynical enough. Indeed, although the word itself is now largely pejorative, you'll find almost everyone revels in a certain amount of cynicism. It's the lifeblood of the satirical comedy of the likes of Ian Hislop, Mark Steel and Jeremy Hardy. Great fictional cynics such as Malcolm Tucker are born of cynicism about politics. It can provide the impulse for the most important investigative journalism. If Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein had been more trustful and credulous of human goodness and sincerity, they would never have broken the Watergate story.

It can provide the impulse for the most important investigative journalism. If we were all habitually trustful and credulous of human goodness and sincerity, then there would be no questioning of dubious foreign interventions, infringements of civil liberties or sharp business practices.

Perhaps the greatest slur against cynicism is that it nurtures a fatalistic pessimism, a belief that nothing can ever be improved. There are lazy forms of cynicism of which this is certainly true. But at its best, cynicism is a greater force for progress than optimism. The optimist underestimates how difficult it is to achieve real change, believing that anything is possible and it's possible now. Only by confronting head-on the reality that all progress is going to be obstructed by vested interests and corrupted by human venality can we create realistic programmes that actually have a chance of success. Progress is more of a challenge for the cynic but also more important and urgent, since for the optimist things aren't that bad and are bound to get better anyway.

This highlights the importance of distinguishing between thinking cynically and acting cynically. There is nothing good to be said for people who cynically deceive to further their own goals and get ahead of others. But that is not what a good cynic inevitably does. Whatever you make of Snowden, whistleblowers and campaigners such as Karen Silkwood and Erin Brockovich are both cynical about what they see and idealistic about what they can do about it. For many years, I too have tried to make sure that the cynicism in my outlook does not lead to cynicism in my behaviour.

That's not the only way in which a proper cynicism challenges the simplistic black-and-white of received opinion. The cynic would surely question the way in which the world is divided into optimists and pessimists. Optimism has various dimensions, and just because some people take a dim view of human nature and some future probabilities, that does not mean they are hardcore pessimists who believe things can only get worse. Cynics refuse to be typecast as Jeremiahs. They are realists who know that the world is not the sun-kissed fantasy peddled by positive-thinking gurus and shysters.

Indeed, the greatest irony of all is that many of the people promoting optimism are unwittingly feeding a view of human nature that is cynical in the very worst sense. Take psychologist and neuroscientist Elaine Fox, who is on Horizon tonight talking about her book Rainy Brain, Sunny Brain. Like many, she traces our tendency to make positive or negative judgments back to our brains and the ways in which they have been cast by our DNA and shaped by our experience. Her upbeat conclusion is that by understanding the neural basis of personality and mood, we can change it and so increase our optimism, health and happiness.

The deeply cynical result of this apparently cheerful viewpoint is that it encourages us to see what we think and believe as products of brain chemistry, rather than as rational responses to the world as it is. Rather than focus on our reasons for being optimistic or pessimistic about, say, the environment, we focus instead on what in our brains is causing us to be optimistic or pessimistic. And that means we seek a resolution of our anxieties not by changing the world, but by changing our minds. If that's not taking a cynical view of human merit and potential, I don't know what is.

So far, I have avoided the easiest way to defend cynicism, which is to point to its illustrious pedigree in the ancient Hellenic school of philosophy from which it gets its name. But I would be cynical about that too. Words change their meanings, and so you cannot dignify the cynicism of now by associating it with its distant ancestor.

Nonetheless, there are lessons for modern cynicism from the likes of Diogenes and Crates. What they show is that a proper cynicism is not a matter of personality but intellectual attitude. Their goal was to blow away the fog and confusion and see reality with lucidity and clarity. The contemporary cynic desires the same. The questioning and doubt is not an end in itself but a means of cutting through the crap and seeing things as they really are.

The ancient Cynics also advocated asceticism and self-sufficiency. There is something of this too in their modern-day counterparts, who are aware that we waste too much of our time and money on things we don't need, but that others require us to buy to make them rich. People who live rigorously by this cynicism are often seen as grumpy killjoys. To be light and joyful today means spending freely, without guilt, on whatever looks as if it will bring us pleasure. That merely shows how deeply our desires have been infected by the power of markets. It is the cynic who actually lives more lightly, unburdened by the pressure to always have more, not relying on purchases to provide happiness and contentment.

Finally, the Cynics were notorious for rejecting all social norms. Diogenes is said to have masturbated in public, while Crates lived on the streets, with only a tattered cloak. Whether anyone is advised to follow these specific examples is questionable, but it is surely true that we do not see enough challenging of tired conventions today. Isn't it astonishing, for example, how, once elected, MPs continue the daft traditions of jeering, guffawing and addressing their colleagues by ridiculous circumlocutory terms such as "the right honourable member"? It comes to something when the most controversial defiance of convention by a politician in recent years was Gordon Brown's refusal to wear a dinner jacket and bow tie. People would perhaps be less cynical about politicians if the politicians themselves would be more cynical.

Perhaps the biggest myth about cynicism is that it deepens with age. I think what really happens is that experience painfully rips away layers of scales from our eyes, and so we do indeed become more cynical about many of the things we naively accepted when younger. But the result of this is to make us see more sharply the difference between what really matters and all the dross and nonsense that clutters up life. So as cynicism about many – perhaps most – things rises, so too does our appreciation and affection for what is good and true. Cynicism leads to more tender feelings towards what is truly lovable. Similarly, doubting the reality of much-professed sincerity is a way of showing that you respect and value the rare and precious real deal.

It's time, therefore, to reclaim cynicism for the forces of light and truth. Forget about the tired old dichotomies of positive and negative, optimistic and pessimistic. We can't make things better unless we see quite how bad they are. We can't do our best unless we guard against our worst. And it's only by being distrustful that we can distinguish between the trustworthy and the unreliable. To do all this we need intelligent cynicism, which is not so much a blanket negativity, but a searchlight for the truly positive.

--------

--------

The test: how cynical are you?

Do you think your pet only wants you for food? Or that Clare Balding is an ambitious back-stabber?

Clare Balding: self-obsessed back-stabber? Photograph: Richard Ansett

There are many ways to express one's cynicism – Diogenes the Cynic, for example, slept in a jar – but the true cynic knows he must be more cynical than anyone else, surprised by nothing but the boundless naivety of those around him. Use this handy checklist to see if you qualify: if you agree with seven or more of the following statements you may count yourself a super-cynic. Not that it means anything. I mean, who cares, right? We're all gonna die alone.

1 You believe that mankind has failed to achieve anything of interest or note since the moon landings were faked.

2 You can look upon the grinning face of George Osborne and still declare that all politicians are as bad as each other.

3 You feel the current cultural debate is missing nothing other than the widespread dissemination of your low opinion of Channel 4's output.

4 You remain convinced that they just throw all the recycling away at the other end.

5 You believe that the editor of the Daily Mail has a dangerously rose-tinted view of human nature.

6 You have a "tendency" to put "inverted commas" "around" "everything".

7 It is your firm conviction that professional wrestling is completely staged, with the outcome of every match determined beforehand, just like professional cricket and professional tennis.

8 You think your dog is only in it for the food.

9 You used to vote Tory out of naked self-interest, but it didn't work so now you don't vote.

10 You stopped watching the Olympics because you could no longer stand the sight of the ambitious, self-obsessed, back-stabbing Clare Balding.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)