'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label totalitarian. Show all posts

Showing posts with label totalitarian. Show all posts

Thursday, 11 July 2024

Wednesday, 15 February 2023

Friday, 20 September 2019

The west’s self-proclaimed custodians of democracy failed to notice it rotting away

British and American elites failed to anticipate the triumph of homegrown demagogues – because they imagined the only threats to democracy lurked abroad writes Pankaj Mishra in The Guardian

Looking ahead to our own era, Gandhi predicted that even “the states that are today nominally democratic” are likely to “become frankly totalitarian”. Gandhi

with Lord and Lady Mountbatten in 1947. Photograph: AP

Looking ahead to our own era, Gandhi predicted that even “the states that are today nominally democratic” are likely to “become frankly totalitarian” since a regime in which “the weakest go to the wall” and a “few capitalist owners” thrive “cannot be sustained except by violence, veiled if not open”.

Inaugurating India’s own experiment with an English-style parliament and electoral system, BR Ambedkar, one of the main authors of the Indian constitution, warned that while the principle of one-person-one-vote conferred political equality, it left untouched grotesque social and economic inequalities. “We must remove this contradiction at the earliest possible moment,” he urged, “or else those who suffer from inequality will blow up the structure of political democracy.”

Today’s elected demagogues, who were chosen by aggrieved voters precisely for their skills in blowing up political democracy, have belatedly alerted many more to this contradiction. But the delay in heeding Ambedkar’s warning has been lethal – and it has left many of our best and brightest stultified by the antics of Trump and Johnson, simultaneously aghast at the sharpened critiques of a resurgent left, and profoundly unable to reckon with the annihilation of democracy by its supposed friends abroad.

Modi has been among the biggest beneficiaries of this intellectual impairment. For decades, India itself greatly benefited from a cold war-era conception of “democracy”, which reduced it to a morally glamorous label for the way rulers are elected, rather than about the kinds of power they hold, or the ways they exercise it.

As a non-communist country that held routine elections, India possessed a matchless international prestige despite consistently failing – worse than many Asian, African, and Latin American countries – in providing its citizens with even the basic components of a dignified existence.

It did not matter to the fetishists of formal and procedural democracy that people in Kashmir and India’s north-eastern border states lived under de facto martial law, where security forces had unlimited licence to massacre and rape, or that a great majority of the Indian population found the promise of equality and dignity underpinned by rule of law and impartial institutions, to be a remote, almost fantastical, ideal.

The halo of virtue around India shone brighter as its governments embraced free markets and communist-run China abruptly emerged as a challenger to the west. Modi profited from an exuberant consensus about India among Anglo-American elites: that democracy had acquired deep roots in Indian soil, fertilising it for the growth of free markets.

As chief minister of the state of Gujarat in 2002, Modi was suspected of a crucial role – ranging from malign inaction to watchful complicity – in an anti-Muslim pogrom of gruesome violence. The US and the European Union denied Modi a visa for several years.

But his record was suddenly forgotten as Modi ascended, with the help of India’s richest businessmen, to power. “There is something thrilling about the rise of Narendra Modi,” Gideon Rachman, the chief foreign affairs columnist for the Financial Times, wrote in April 2014. Rupert Murdoch, of course, anointed Modi as India’s “best leader with best policies since independence”.

But Barack Obama also chose to hail Modi for reflecting “the dynamism and potential of India’s rise”. As Modi arrived in Silicon Valley in 2015 – just as his government was shutting down the internet in Kashmir – Sheryl Sandberg declared she was changing her Facebook profile in order to honour the Indian leader.

In the next few days, Modi will address thousands of affluent Indian-Americans in the company of Trump in Houston, Texas. While his government builds detention camps for hundreds of thousands Muslims it has abruptly rendered stateless, he will receive a commendation from Bill Gates for building toilets.

The fawning by Western politicians, businessmen, and journalists over a man credibly accused of complicity in a mass murder is a much bigger scandal than Jeffrey Epstein’s donations to MIT. But it has gone almost wholly unremarked in mainstream circles partly because democratic and free-marketeering India was the great non-white hope of the ideological children of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher who still dominate our discourse: India was a gilded oriental mirror in which they could cherish themselves.

This moral vanity explains how even sentinels of the supposedly reasonable centre, such as Obama and the Financial Times, came to condone demagoguery abroad – and, more importantly, how they failed to anticipate its eruption at home.

Even the most fleeting glance at history shows that the contradiction Ambedkar identified in India – which enabled Modi’s rise – has long bedevilled the emancipatory promise of democratic equality. In 1909, Max Weber asked: “How are freedom and democracy in the long run at all possible under the domination of highly developed capitalism?”

The decades of atrocity that followed answered Weber’s question with a grisly spectacle. The fraught and extremely limited western experiment with democracy did better only after social-welfarism, widely adopted after 1945, emerged to defang capitalism, and meet halfway the formidable old challenge of inequality. But the rule of demos still seemed remote.

The Cambridge political theorist John Dunn was complaining as early as 1979 that while democratic theory had become the “public cant of the modern world”, democratic reality had grown “pretty thin on the ground”. Since then, that reality has grown flimsier, corroded by a financialised mode of capitalism that has held Anglo-American politicians and journalists in its thrall since the 1980s.

What went unnoticed until recently was that the chasm between a political system that promises formal equality and a socio-economic system that generates intolerable inequality had grown much wider. It eventually empowered the demagogues who now rule us. In other words, modern democracies have for decades been lurching towards moral and ideological bankruptcy – unprepared by their own publicists to cope with the political and environmental disasters that unregulated capitalism ceaselessly inflicts, even on such winners of history as Britain and the US.

Having laboured to exclude a smelly past of ethnocide, slavery and racism – and the ongoing stink of corporate venality – from their perfumed notion of Anglo-American superiority, the promoters of democracy have no nose for its true enemies. Ripe for superannuation but still entrenched on the heights of politics and journalism, they repetitively ventilate their rage and frustration, or whinge incessantly about “cancel culture” and the “radical left”, it is because that is all they can do. Their own mind-numbing simplicities about democracy, its enemies, friends, the free world, and all that sort of thing, have doomed them to experience the contemporary world as an endless series of shocks and debacles.

Illustration: Nate Kitch/The Guardian

Anglo-American lamentations about the state of democracy have been especially loud ever since Boris Johnson joined Donald Trump in the leadership of the free world. For a very long time, Britain and the United States styled themselves as the custodians and promoters of democracy globally, fighting a great moral battle against its foreign enemies. From the cold war through to the “war on terror”, the Caesarism that afflicted other nations was seen as peculiar to Asian and African peoples, or blamed on the despotic traditions of Russians or Chinese, on African tribalism, Islam, or the “Arab mind”.

But this analysis – amplified in a thousand books and opinion columns that located the enemies of democracy among menacingly alien people and their inferior cultures – did not prepare its audience for the sight of blond bullies perched atop the world’s greatest democracies. The barbarians, it turns out, were never at the gate; they have been ruling us for some time.

The belated shock of this realisation has made impotent despair the dominant tone of establishment commentary on the events of the past few years. But this acute helplessness betrays something more significant. While democracy was being hollowed out in the west, mainstream politicians and columnists concealed its growing void by thumping their chests against its supposed foreign enemies – or cheerleading its supposed foreign friends.

Decades of this deceptive and deeply ideological discourse about democracy have left many of us struggling to understand how it was hollowed from within – at home and abroad. Consider the stunning fact that India, billed as the world’s largest democracy, has descended into a form of Hindu supremacism – and, in Kashmir, into racist imperialism of the kind it liberated itself from in 1947.

Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist government is enforcing a seemingly endless curfew in the valley of Kashmir, imprisoning thousands of people without charge, cutting phone lines and the internet, and allegedly torturing suspected dissenters. Modi has established – to massive Indian acclaim – the regime of brute power and mendacity that Mahatma Gandhi explicitly warned his compatriots against: “English rule without the Englishman”.

All this while “the mother of parliaments” reels under English rule with a particularly reckless Englishman, and Israel – the “only democracy in the Middle East” – holds another election in which millions of Palestinians under its ethnocratic rule are denied a vote.

The vulnerabilities of western democracy were evident long ago to the Asian and African subjects of the British empire. Gandhi, who saw democracy as literally the rule of the people, the demos, claimed that it was merely “nominal” in the west. It could have no reality so long as “the wide gulf between the rich and the hungry millions persists” and voters “take their cue from their newspapers which are often dishonest”.

Anglo-American lamentations about the state of democracy have been especially loud ever since Boris Johnson joined Donald Trump in the leadership of the free world. For a very long time, Britain and the United States styled themselves as the custodians and promoters of democracy globally, fighting a great moral battle against its foreign enemies. From the cold war through to the “war on terror”, the Caesarism that afflicted other nations was seen as peculiar to Asian and African peoples, or blamed on the despotic traditions of Russians or Chinese, on African tribalism, Islam, or the “Arab mind”.

But this analysis – amplified in a thousand books and opinion columns that located the enemies of democracy among menacingly alien people and their inferior cultures – did not prepare its audience for the sight of blond bullies perched atop the world’s greatest democracies. The barbarians, it turns out, were never at the gate; they have been ruling us for some time.

The belated shock of this realisation has made impotent despair the dominant tone of establishment commentary on the events of the past few years. But this acute helplessness betrays something more significant. While democracy was being hollowed out in the west, mainstream politicians and columnists concealed its growing void by thumping their chests against its supposed foreign enemies – or cheerleading its supposed foreign friends.

Decades of this deceptive and deeply ideological discourse about democracy have left many of us struggling to understand how it was hollowed from within – at home and abroad. Consider the stunning fact that India, billed as the world’s largest democracy, has descended into a form of Hindu supremacism – and, in Kashmir, into racist imperialism of the kind it liberated itself from in 1947.

Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist government is enforcing a seemingly endless curfew in the valley of Kashmir, imprisoning thousands of people without charge, cutting phone lines and the internet, and allegedly torturing suspected dissenters. Modi has established – to massive Indian acclaim – the regime of brute power and mendacity that Mahatma Gandhi explicitly warned his compatriots against: “English rule without the Englishman”.

All this while “the mother of parliaments” reels under English rule with a particularly reckless Englishman, and Israel – the “only democracy in the Middle East” – holds another election in which millions of Palestinians under its ethnocratic rule are denied a vote.

The vulnerabilities of western democracy were evident long ago to the Asian and African subjects of the British empire. Gandhi, who saw democracy as literally the rule of the people, the demos, claimed that it was merely “nominal” in the west. It could have no reality so long as “the wide gulf between the rich and the hungry millions persists” and voters “take their cue from their newspapers which are often dishonest”.

Looking ahead to our own era, Gandhi predicted that even “the states that are today nominally democratic” are likely to “become frankly totalitarian”. Gandhi

with Lord and Lady Mountbatten in 1947. Photograph: AP

Looking ahead to our own era, Gandhi predicted that even “the states that are today nominally democratic” are likely to “become frankly totalitarian” since a regime in which “the weakest go to the wall” and a “few capitalist owners” thrive “cannot be sustained except by violence, veiled if not open”.

Inaugurating India’s own experiment with an English-style parliament and electoral system, BR Ambedkar, one of the main authors of the Indian constitution, warned that while the principle of one-person-one-vote conferred political equality, it left untouched grotesque social and economic inequalities. “We must remove this contradiction at the earliest possible moment,” he urged, “or else those who suffer from inequality will blow up the structure of political democracy.”

Today’s elected demagogues, who were chosen by aggrieved voters precisely for their skills in blowing up political democracy, have belatedly alerted many more to this contradiction. But the delay in heeding Ambedkar’s warning has been lethal – and it has left many of our best and brightest stultified by the antics of Trump and Johnson, simultaneously aghast at the sharpened critiques of a resurgent left, and profoundly unable to reckon with the annihilation of democracy by its supposed friends abroad.

Modi has been among the biggest beneficiaries of this intellectual impairment. For decades, India itself greatly benefited from a cold war-era conception of “democracy”, which reduced it to a morally glamorous label for the way rulers are elected, rather than about the kinds of power they hold, or the ways they exercise it.

As a non-communist country that held routine elections, India possessed a matchless international prestige despite consistently failing – worse than many Asian, African, and Latin American countries – in providing its citizens with even the basic components of a dignified existence.

It did not matter to the fetishists of formal and procedural democracy that people in Kashmir and India’s north-eastern border states lived under de facto martial law, where security forces had unlimited licence to massacre and rape, or that a great majority of the Indian population found the promise of equality and dignity underpinned by rule of law and impartial institutions, to be a remote, almost fantastical, ideal.

The halo of virtue around India shone brighter as its governments embraced free markets and communist-run China abruptly emerged as a challenger to the west. Modi profited from an exuberant consensus about India among Anglo-American elites: that democracy had acquired deep roots in Indian soil, fertilising it for the growth of free markets.

As chief minister of the state of Gujarat in 2002, Modi was suspected of a crucial role – ranging from malign inaction to watchful complicity – in an anti-Muslim pogrom of gruesome violence. The US and the European Union denied Modi a visa for several years.

But his record was suddenly forgotten as Modi ascended, with the help of India’s richest businessmen, to power. “There is something thrilling about the rise of Narendra Modi,” Gideon Rachman, the chief foreign affairs columnist for the Financial Times, wrote in April 2014. Rupert Murdoch, of course, anointed Modi as India’s “best leader with best policies since independence”.

But Barack Obama also chose to hail Modi for reflecting “the dynamism and potential of India’s rise”. As Modi arrived in Silicon Valley in 2015 – just as his government was shutting down the internet in Kashmir – Sheryl Sandberg declared she was changing her Facebook profile in order to honour the Indian leader.

In the next few days, Modi will address thousands of affluent Indian-Americans in the company of Trump in Houston, Texas. While his government builds detention camps for hundreds of thousands Muslims it has abruptly rendered stateless, he will receive a commendation from Bill Gates for building toilets.

The fawning by Western politicians, businessmen, and journalists over a man credibly accused of complicity in a mass murder is a much bigger scandal than Jeffrey Epstein’s donations to MIT. But it has gone almost wholly unremarked in mainstream circles partly because democratic and free-marketeering India was the great non-white hope of the ideological children of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher who still dominate our discourse: India was a gilded oriental mirror in which they could cherish themselves.

This moral vanity explains how even sentinels of the supposedly reasonable centre, such as Obama and the Financial Times, came to condone demagoguery abroad – and, more importantly, how they failed to anticipate its eruption at home.

Even the most fleeting glance at history shows that the contradiction Ambedkar identified in India – which enabled Modi’s rise – has long bedevilled the emancipatory promise of democratic equality. In 1909, Max Weber asked: “How are freedom and democracy in the long run at all possible under the domination of highly developed capitalism?”

The decades of atrocity that followed answered Weber’s question with a grisly spectacle. The fraught and extremely limited western experiment with democracy did better only after social-welfarism, widely adopted after 1945, emerged to defang capitalism, and meet halfway the formidable old challenge of inequality. But the rule of demos still seemed remote.

The Cambridge political theorist John Dunn was complaining as early as 1979 that while democratic theory had become the “public cant of the modern world”, democratic reality had grown “pretty thin on the ground”. Since then, that reality has grown flimsier, corroded by a financialised mode of capitalism that has held Anglo-American politicians and journalists in its thrall since the 1980s.

What went unnoticed until recently was that the chasm between a political system that promises formal equality and a socio-economic system that generates intolerable inequality had grown much wider. It eventually empowered the demagogues who now rule us. In other words, modern democracies have for decades been lurching towards moral and ideological bankruptcy – unprepared by their own publicists to cope with the political and environmental disasters that unregulated capitalism ceaselessly inflicts, even on such winners of history as Britain and the US.

Having laboured to exclude a smelly past of ethnocide, slavery and racism – and the ongoing stink of corporate venality – from their perfumed notion of Anglo-American superiority, the promoters of democracy have no nose for its true enemies. Ripe for superannuation but still entrenched on the heights of politics and journalism, they repetitively ventilate their rage and frustration, or whinge incessantly about “cancel culture” and the “radical left”, it is because that is all they can do. Their own mind-numbing simplicities about democracy, its enemies, friends, the free world, and all that sort of thing, have doomed them to experience the contemporary world as an endless series of shocks and debacles.

Wednesday, 21 August 2013

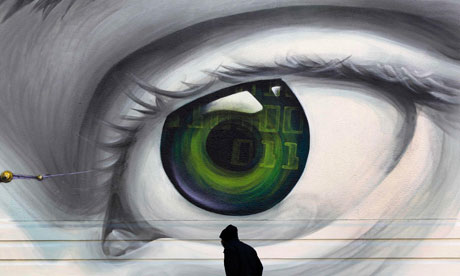

So the innocent have nothing to fear?

After David Miranda we now know where this leads

The destructive power of state snooping is on display for all to see. The press must not yield to this intimidation

'But it remains worrying that many otherwise liberal-minded Britons seem reluctant to take seriously the abuses revealed in the nature and growth of state surveillance.' Photograph: Yannis Behrakis/Reuters

You've had your fun: now we want the stuff back. With these words the British government embarked on the most bizarre act of state censorship of the internet age. In a Guardian basement, officials from GCHQ gazed with satisfaction on a pile of mangled hard drives like so many book burners sent by the Spanish Inquisition. They were unmoved by the fact that copies of the drives were lodged round the globe. They wanted their symbolic auto-da-fe. Had the Guardian refused this ritual they said they would have obtained a search and destroy order from a compliant British court.

Two great forces are now in fierce but unresolved contention. The material revealed by Edward Snowden through the Guardian and the Washington Post is of a wholly different order from WikiLeaks and other recent whistle-blowing incidents. It indicates not just that the modern state is gathering, storing and processing for its own ends electronic communication from around the world; far more serious, it reveals that this power has so corrupted those wielding it as to put them beyond effective democratic control. It was not the scope of NSA surveillance that led to Snowden's defection. It was hearing his boss lie to Congress about it for hours on end.

Last week in Washington, Congressional investigators discovered that the America's foreign intelligence surveillance court, a body set up specifically to oversee the NSA, had itself been defied by the agency "thousands of times". It was victim to "a culture of misinformation" as orders to destroy intercepts, emails and files were simply disregarded; an intelligence community that seems neither intelligent nor a community commanding a global empire that could suborn the world's largest corporations, draw up targets for drone assassination, blackmail US Muslims into becoming spies and haul passengers off planes.

Yet like all empires, this one has bred its own antibodies. The American (or Anglo-American?) surveillance industry has grown so big by exploiting laws to combat terrorism that it is as impossible to manage internally as it is to control externally. It cannot sustain its own security. Some two million people were reported to have had access to the WikiLeaks material disseminated by Bradley Manning from his Baghdad cell. Snowden himself was a mere employee of a subcontractor to the NSA, yet had full access to its data. The thousands, millions, billions of messages now being devoured daily by US data storage centres may be beyond the dreams of Space Odyssey's HAL 9000. But even HAL proved vulnerable to human morality. Manning and Snowden cannot have been the only US officials to have pondered blowing a whistle on data abuse. There must be hundreds more waiting in the wings – and always will be.

There is clearly a case for prior censorship of some matters of national security. A state secret once revealed cannot be later rectified by a mere denial. Yet the parliamentary and legal institutions for deciding these secrets are plainly no longer fit for purpose. They are treated by the services they supposedly supervise with falsehoods and contempt. In America, the constitution protects the press from pre-publication censorship, leaving those who reveal state secrets to the mercy of the courts and the judgment of public debate – hence the Putinesque treatment of Manning and Snowden. But at least Congress has put the US director of national intelligence, James Clapper, under severe pressure. Even President Barack Obama has welcomed the debate and accepted that the Patriot Act may need revision.

In Britain, there has been no such response. GCHQ could boast to its American counterpart of its "light oversight regime compared to the US". Parliamentary and legal control is a charade, a patsy of the secrecy lobby. The press, normally robust in its treatment of politicians, seems cowed by a regime of informal notification of "defence sensitivity". This D-Notice system used to be confined to cases where the police felt lives to be at risk in current operations. In the case of Snowden the D-Notice has been used to warn editors off publishing material potentially embarrassing to politicians and the security services under the spurious claim that it "might give comfort to terrorists".

Most of the British press (though not the BBC, to its credit) has clearly felt inhibited. As with the "deterrent" smashing of Guardian hard drives and the harassing of David Miranda at Heathrow, a regime of prior restraint has been instigated in Britain whose apparent purpose seems to be simply to show off the security services as macho to their American friends.

Those who question the primacy of the "mainstream" media in the digital age should note that it has been two traditional newspapers, in London and Washington, that have researched, co-ordinated and edited the Snowden revelations. They have even held back material that the NSA and GCHQ had proved unable to protect. No blog, Twitter or Facebook campaign has the resources or the clout to confront the power of the state.

There is no conceivable way copies of the Snowden revelations seized this week at Heathrow could aid terrorism or "threaten the security of the British state" – as charged today by Mark Pritchard, an MP on the parliamentary committee on national security strategy. When the supposed monitors of the secret services merely parrot their jargon against press freedom, we should know this regime is not up to its job.

The war between state power and those holding it to account needs constant refreshment. As Snowden shows, the whistleblowers and hacktivists can win the occasional skirmish. But it remains worrying that many otherwise liberal-minded Britons seem reluctant to take seriously the abuses revealed in the nature and growth of state surveillance. The arrogance of this abuse is now widespread. The same police force that harassed Miranda for nine hours at Heathrow is the one recently revealed as using surveillance to blackmail Lawrence family supporters and draw up lists of trouble-makers to hand over to private contractors. We can see where this leads.

I hesitate to draw parallels with history, but I wonder how those now running the surveillance state – and their appeasers – would have behaved under the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century. We hear today so many phrases we have heard before. The innocent have nothing to fear. Our critics merely comfort the enemy. You cannot be too safe. Loyalty is all. As one official said in wielding his legal stick over the Guardian: "You have had your debate. There's no need to write any more."

Yes, there bloody well is.

Saturday, 8 December 2012

Julian Assange: the fugitive

Julian Assange has been holed up in the Ecuadorian embassy for six months. In a rare interview, we ask the WikiLeaks founder about reports of illness, paranoia – and if he'll ever come out

Julian Assange: 'I suppose it’s quite nice that people are worried about me.’ Photograph: Gian Paul Lozza for the Guardian

The Ecuadorian embassy in Knightsbridge looks rather lavish from the street, but inside it's not much bigger than a family apartment. The armed police guard outside is reported to cost £12,000 a day, but I can see only three officers, all of whom look supremely bored. Christmas shoppers heading for Harrods next door bustle by, indifferent or oblivious to the fact that they pass within feet of one of the world's most famous fugitives.

It's almost six months since Julian Assange took refuge in the embassy, and a state of affairs that was at first sensational is slowly becoming surreal. Ecuador has granted its guest formal asylum, but the WikiLeaks founder can't get as far as Harrods, let alone to South America, because the moment he leaves the embassy, he will be arrested – even if he comes out in a diplomatic bag or handcuffed to the ambassador – and extradited toSweden to face allegations of rape and sexual assault. Assange says he'll happily go to Stockholm, providing the Swedish government guarantees he won't then be extradited on to the US, where he fears he will be tried for espionage. Stockholm says no guarantee can be given, because that decision would lie with the courts. And so the weeks have stretched into months, and may yet stretch on into years.

Making the whole arrangement even stranger are the elements of normality. A receptionist buzzes me in and checks my ID, and then a businesslike young woman, Assange's assistant, leads me through into a standard-issue meeting room, where a young man who has something to do with publicity at Assange's publishers is sitting in front of a laptop. There are pieces of camera equipment and a tripod; someone suggests coffee. It all looks and feels like an ordinary interview.

But when Assange appears, he seems more like an in-patient than an interviewee, his opening words slow and hesitant, the voice so cracked as to be barely audible. If you have ever visited someone convalescing after a breakdown, his demeanour would be instantly recognisable. Admirers cast him as the new Jason Bourne, but in these first few minutes I worry he may be heading more towards Miss Havisham.

Assange tells me he sees visitors most days, but I'm not sure how long it was since a stranger was here, so I ask if this feels uncomfortable. "No, I look forward to the company. And, in some cases, the adversary." His gaze flickers coolly. "We'll see which." He shrugs off recent press reports of a chronic lung infection, but says: "I suppose it's quite nice, though, actually, that people are worried about me." Former hostages often talk about what it meant to hear their name on the radio and know the outside world was still thinking of them. Have the reports of his health held something similar for him? "Absolutely. Though I felt that much more keenly when I was in prison."

Assange spent 10 days in jail in December 2010, before being bailed to the stately home of a supporter in Suffolk. There, he was free to come and go in daylight hours, yet he says he felt more in captivity then than he does now. "During the period of house arrest, I had an electronic manacle around my leg for 24 hours a day, and for someone who has tried to give others liberty all their adult life, that is absolutely intolerable. And I had to go to the police at a specific time every day – every day – Christmas Day, New Year's Day – for over 550 days in a row." His voice is warming now, barbed with indignation. "One minute late would mean being placed into prison immediately." Despite being even more confined here, he's now the author of his own confinement, so he feels freer?

"Precisely."

And now he is the author of a new book, Cypherpunks: Freedom And The Future Of TheInternet. Based on conversations and interviews with three other cypherpunks – internet activists fighting for online privacy – it warns that we are sleepwalking towards a "new transnational dystopia". Its tone is portentous – "The internet, our greatest tool of emancipation, has been transformed into the most dangerous facilitator of totalitarianism we have ever seen" – and its target audience anyone who has ever gone online or used a mobile phone.

"The last 10 years have seen a revolution in interception technology, where we have gone from tactical interception to strategic interception," he explains. "Tactical interception is the one that we are all familiar with, where particular individuals become of interest to the state or its friends: activists, drug dealers, and so on. Their phones are intercepted, their email communication is intercepted, their friends are intercepted, and so on. We've gone from that situation to strategic interception, where everything flowing out of or into a country – and for some countries domestically as well – is intercepted and stored permanently. Permanently. It's more efficient to take and store everything than it is to work out who you want to intercept."

The change is partly down to economies of scale: interception costs have been halving every two years, whereas the human population has been doubling only every 20. "So we've now reached this critical juncture where it is possible to intercept everyone – every SMS, every email, every mobile phone call – and store it and search it for a nominal fee by governmental standards. A kit produced in South Africa can store and index all telecommunications traffic in and out of a medium-sized nation for $10m a year." And the public has no idea, due largely to a powerful lobby dedicated to keeping it in the dark, and partly to the legal and technological complexity. So we spend our days actively assisting the state's theft of private information about us, by putting it all online.

"The penetration of the Stasi in East Germany is reported to be up to 10% of the population – one in 10 at some stage acted as informers – but the penetration of Facebook in countries like Iceland is 88%, and those people are informing much more frequently and in much more detail than they ever were in the Stasi. And they're not even getting paid to do it! They're doing it because they feel they'll be excluded from social opportunities otherwise. So we're now in this unique position where we have all the ingredients for a turnkey totalitarian state."

In this dystopian future, Assange sees only one way to protect ourselves: cryptography. Just as handwashing was once a novelty that became part of everyday life, and crucial to protecting our health, so, too, will we have to get used to encrypting our online activity. "A well-defined mathematical algorithm can encrypt something quickly, but to decrypt it would take billions of years – or trillions of dollars' worth of electricity to drive the computer. So cryptography is the essential building block of independence for organisations on the internet, just like armies are the essential building blocks of states, because otherwise one state just takes over another. There is no other way for our intellectual life to gain proper independence from the security guards of the world, the people who control physical reality."

Assange talks in the manner of a man who has worked out that the Earth is round, while everyone else is lumbering on under the impression that it is flat. It makes you sit up and listen, but raises two doubts about how to judge his thesis. There's no debate that Assange knows more about the subject than almost anyone alive, and the case he makes is both compelling and scary. But there's a question mark over his own credentials as a crusader against abuses of power, and another over his frame of mind. After all the dramas of the last two and a half years, it's hard to read his book without wondering, is Assange a hypocrite – and is he a reliable witness?

Assange in the Ecuadorian embassy: ‘It would be nice to go for a walk in the woods.’ Photograph: Gian Paul Lozza for the Guardian

Assange in the Ecuadorian embassy: ‘It would be nice to go for a walk in the woods.’ Photograph: Gian Paul Lozza for the Guardian

Prodigiously gifted, he is often described as a genius, but he has the autodidact's tendency to come across as simultaneously credulous and a bit slapdash. He can leap from one country to another when characterising surveillance practices, as if all nations were analogous, and refers to the communications data bill currently before the UK parliament in such alarmist terms that I didn't even recognise the legislation and thought he must be talking about a bill I'd never heard of. "A bill promulgated by the Queen, no less!" he emphasises, as if the government could propose any other variety, before implying that it will give the state the right to read every email and listen in on every mobile phone call, which is simply not the case. It's the age-old dilemma: are we being warned by a uniquely clear-sighted Cassandra, or by a paranoid conspiracy theorist whose current circumstances only confirm all his suspicions of sinister secret state forces at work?

But first, the hypocrisy question. I say many readers will wonder why, if it's so outrageous for the state to read our emails, it is OK for WikiLeaks to publish confidential state correspondence.

"It's all about power," he replies. "And accountability. The greater the power, the more need there is for transparency, because if the power is abused, the result can be so enormous. On the other hand, those people who do not have power, we mustn't reduce their power even more by making them yet more transparent."

Many people would say Assange himself is immensely powerful, and should be held to a higher standard of accountability and transparency. "I think that is correct," he agrees. So was WikiLeaks' decision to publish Afghan informers' names unredacted an abuse of power? Assange draws himself up and lets rip. "This is absurd propaganda. Basic kindergarten rhetoric. There has been no official accusation that any of our publications over a six-year period have resulted in the deaths of a single person – a single person – and this shows you the incredible political power of the Pentagon, that it is able to attempt to reframe the debate in that way."

Others have wondered how he could make a chatshow for a state-owned Moscow TV station. "I've never worked for a Russian state-owned television channel. That's just ridiculous – the usual propaganda rubbish." He spells it out slowly and deliberately. "I have a TV production company, wholly owned by me. We work in partnership with Dartmouth Films, a London production company, to produce a 12-part TV series about activists and thinkers from around the world. Russia Today was one of more than 20 different media organisations that purchased a licence. That is all." There is no one to whom he wouldn't sell a licence? "Absolutely not. In order to go to the hospital, we must put Shell in our car. In order to make the maximum possible impact for our sources, we have to deal with organisations like the New York Times and the Guardian." He pauses. "It doesn't mean we approve of these organisations."

I try twice to ask how a campaigner for free speech can condone Ecuador's record on press controls, but I'm not sure he hears, because he is off into a coldly furious tirade against the Guardian. The details of the dispute are of doubtful interest to a wider audience, but in brief: WikiLeaks worked closely with both the Guardian and the New York Times in 2010 to publish huge caches of confidential documents, before falling out very badly with both. He maintains that the Guardian broke its word and behaved disgracefully, but he seems to have a habit of falling out with erstwhile allies. Leaving aside the two women in Sweden who were once his admirers and now allege rape and sexual assault, things also ended badly with Canongate, a small publisher that paid a large advance for his ghosted autobiography, only to have Assange pull out of the project after reading the first draft. It went ahead and published anyway, but lost an awful lot of money. Several staff walked out of WikiLeaks in 2010, including a close colleague, Daniel Domscheit-Berg, who complained that Assange was behaving "like some kind of emperor or slave trader".

It clearly isn't news to Assange that even some of his supporters despair of an impossible personality, and blame his problems on hubris, but he isn't having any of it. I ask how he explains why so many relationships have soured. "They haven't." OK, let's go through them one by one. The relationship with Canongate…

"Oh my God!" he interrupts angrily, raising his voice. "These people, we told them not to do that. They were wrong to do it, to violate the author's copyright like that." Did he ever consider giving his advance back? "Canongate owes me money. I have not seen a single cent from this book. Canongate owes me hundreds of thousands of pounds." But if he hasn't seen any money, it's because the advance was deposited in Assange's lawyers' bank account, to go towards paying their fees. Then the lawyers complained that the advance didn't cover the fees, and Assange fell out with them, too.

"I was in a position last year where everybody thought they could have a free kick. They thought that because I was involved in an enormous conflict with the United Statesgovernment. The law firm was another. But those days are gone."

What about the fracture with close colleagues at WikiLeaks? "No!" he practically shouts. But Domscheit-Berg got so fed up with Assange that he quit, didn't he? "No, no, no, no, no. Domscheit-Berg had a minor role within WikiLeaks, and he was suspended by me on 25 August 2010. Suspended." Well, that's my point – here was somebody else with whom Assange fell out. "Be serious here! Seriously – my God. What we are talking about here in our work is the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people – hundreds of thousands – that we have exposed and documented. And your question is about, did we suspend someone back in 2010?" My point was that there is a theme of his relationships turning sour. "There is not!" he shouts.

I don't blame Assange for getting angry. As he sees it, he's working tirelessly to expose state secrecy and save us all from tyranny. He has paid for it with his freedom, and fears for his life. Isn't it obvious that shadowy security forces are trying to make him look either mad or bad, to discredit WikiLeaks? If that's true, then his flaws are either fabricated, or neither here nor there. But the messianic grandiosity of his self-justification is a little disconcerting.

I ask if he has considered the possibility that he might live in this embassy for the rest of his life. "I've considered the possibility. But it sure beats supermax [maximum security prison]." Does he worry about his mental health? "Only that it is nice to go for a walk in the woods, and it's important – because I have to look after so many people – that I am close to the peak of my performance at all times, because we are involved in an adversarial conflict and any misjudgment will be seized upon." Does he ever try to work out whether he is being paranoid? "Yes. I have a lot of experience. I mean, I have 22 years of experience." He'd rather not say to whom he turns for emotional support, "because we are in an adversarial conflict", but he misses his family the most. His voice slows and drops again.

"The situation is, er, the communication situation is difficult. Some of them have had to change their names, move location. Because they have suffered death threats, trying to get at me. There have been explicit proposals through US rightwing groups to target my son, for example, to get at me. The rest of the family, having seen that, has taken precautions in response." But it has all been worth it, he says, because of what he's achieved.

"Changes in electoral outcomes, contributions to revolutions in the Middle East, and the knowledge that we have contributed towards the Iraqi people and the Afghan people. And also the end of the Iraq war, which we had an important contribution towards. You can look that up. It's to do with the circumstances under which immunity was refused to US troops at the end of 2011. The documents we'd published directly were cited by Iraqis as a reason for discontinuing the immunity. And the US said it would refuse to stay without continued immunity."

Assange says he can't say anything about the allegations of rape and sexual assault for legal reasons, but he predicts that the extradition will be dropped. The grounds for his confidence are not clear, because in the next breath he adds: "Sweden refuses to behave like a reasonable state. It refuses to give a guarantee that I won't be extradited to the US." But Sweden says the decision lies with the courts, not the government. "That is not true," he snaps. "It is absolutely false. The government has the final say." If he's right, and it really is as unequivocal as that, why all the legal confusion? "Because there are enormous powers at play," he says, heavy with exasperation. "Controversy is a result of people trying to shift political opinion one way or another."

And so his surreal fugitive existence continues, imprisoned in a tiny piece of Ecuador in Knightsbridge. He has a special ultraviolet lamp to compensate for the lack of sunlight, but uses it "with great trepidation", having burned himself the first time he tried it. His assistant, who may or may not be his girlfriend – she has been reported as such, but denies it when I check – is a constant presence, and by his account WikiLeaks continues to thrive. Reports that it has basically imploded, undone by the dramas and rows surrounding its editor-in-chief, are dismissed as yet more smears. The organisation will have published more than a million leaks this year, he says, and will publish "considerably more" in 2013. I'm pretty sure he has found a way to get rid of his electronic tag, because when I ask, he stares with a faint gnomic smile. "Umm… I'd prefer not to comment."

Assange has been called a lot of things – a terrorist, a visionary, a rapist, a freedom warrior. At moments he reminds me of a charismatic cult leader but, given his current predicament, it's hardly surprising if loyalty counts more than critical distance in his world. The only thing I could say with confidence is that he is a control freak. The persona he most frequently ascribes to himself is "gentleman", a curiously courtly term for a cypher–punk to choose, so I ask him to explain.

"What is a gentleman? I suppose it's, you know, a nice section of Australian culture that perhaps wouldn't be recognised in thieving metropolises like London. The importance of being honourable, and keeping your word, and acting like a gentleman. It's someone who has the courage of their convictions, who doesn't bow to pressure, who doesn't exploit people who are weaker than they are. Who acts in an honourable way."

Does that describe him? "No, but it describes an ideal I believe men should strive for."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)