Illustration: Nate Kitch/The Guardian

Anglo-American lamentations about the state of democracy have been especially loud ever since Boris Johnson joined Donald Trump in the leadership of the free world. For a very long time, Britain and the United States styled themselves as the custodians and promoters of democracy globally, fighting a great moral battle against its foreign enemies. From the cold war through to the “war on terror”, the Caesarism that afflicted other nations was seen as peculiar to Asian and African peoples, or blamed on the despotic traditions of Russians or Chinese, on African tribalism, Islam, or the “Arab mind”.

But this analysis – amplified in a thousand books and opinion columns that located the enemies of democracy among menacingly alien people and their inferior cultures – did not prepare its audience for the sight of blond bullies perched atop the world’s greatest democracies. The barbarians, it turns out, were never at the gate; they have been ruling us for some time.

The belated shock of this realisation has made impotent despair the dominant tone of establishment commentary on the events of the past few years. But this acute helplessness betrays something more significant. While democracy was being hollowed out in the west, mainstream politicians and columnists concealed its growing void by thumping their chests against its supposed foreign enemies – or cheerleading its supposed foreign friends.

Decades of this deceptive and deeply ideological discourse about democracy have left many of us struggling to understand how it was hollowed from within – at home and abroad. Consider the stunning fact that India, billed as the world’s largest democracy, has descended into a form of Hindu supremacism – and, in Kashmir, into racist imperialism of the kind it liberated itself from in 1947.

Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist government is enforcing a seemingly endless curfew in the valley of Kashmir, imprisoning thousands of people without charge, cutting phone lines and the internet, and allegedly torturing suspected dissenters. Modi has established – to massive Indian acclaim – the regime of brute power and mendacity that Mahatma Gandhi explicitly warned his compatriots against: “English rule without the Englishman”.

All this while “the mother of parliaments” reels under English rule with a particularly reckless Englishman, and Israel – the “only democracy in the Middle East” – holds another election in which millions of Palestinians under its ethnocratic rule are denied a vote.

The vulnerabilities of western democracy were evident long ago to the Asian and African subjects of the British empire. Gandhi, who saw democracy as literally the rule of the people, the demos, claimed that it was merely “nominal” in the west. It could have no reality so long as “the wide gulf between the rich and the hungry millions persists” and voters “take their cue from their newspapers which are often dishonest”.

Anglo-American lamentations about the state of democracy have been especially loud ever since Boris Johnson joined Donald Trump in the leadership of the free world. For a very long time, Britain and the United States styled themselves as the custodians and promoters of democracy globally, fighting a great moral battle against its foreign enemies. From the cold war through to the “war on terror”, the Caesarism that afflicted other nations was seen as peculiar to Asian and African peoples, or blamed on the despotic traditions of Russians or Chinese, on African tribalism, Islam, or the “Arab mind”.

But this analysis – amplified in a thousand books and opinion columns that located the enemies of democracy among menacingly alien people and their inferior cultures – did not prepare its audience for the sight of blond bullies perched atop the world’s greatest democracies. The barbarians, it turns out, were never at the gate; they have been ruling us for some time.

The belated shock of this realisation has made impotent despair the dominant tone of establishment commentary on the events of the past few years. But this acute helplessness betrays something more significant. While democracy was being hollowed out in the west, mainstream politicians and columnists concealed its growing void by thumping their chests against its supposed foreign enemies – or cheerleading its supposed foreign friends.

Decades of this deceptive and deeply ideological discourse about democracy have left many of us struggling to understand how it was hollowed from within – at home and abroad. Consider the stunning fact that India, billed as the world’s largest democracy, has descended into a form of Hindu supremacism – and, in Kashmir, into racist imperialism of the kind it liberated itself from in 1947.

Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist government is enforcing a seemingly endless curfew in the valley of Kashmir, imprisoning thousands of people without charge, cutting phone lines and the internet, and allegedly torturing suspected dissenters. Modi has established – to massive Indian acclaim – the regime of brute power and mendacity that Mahatma Gandhi explicitly warned his compatriots against: “English rule without the Englishman”.

All this while “the mother of parliaments” reels under English rule with a particularly reckless Englishman, and Israel – the “only democracy in the Middle East” – holds another election in which millions of Palestinians under its ethnocratic rule are denied a vote.

The vulnerabilities of western democracy were evident long ago to the Asian and African subjects of the British empire. Gandhi, who saw democracy as literally the rule of the people, the demos, claimed that it was merely “nominal” in the west. It could have no reality so long as “the wide gulf between the rich and the hungry millions persists” and voters “take their cue from their newspapers which are often dishonest”.

Looking ahead to our own era, Gandhi predicted that even “the states that are today nominally democratic” are likely to “become frankly totalitarian”. Gandhi

with Lord and Lady Mountbatten in 1947. Photograph: AP

Looking ahead to our own era, Gandhi predicted that even “the states that are today nominally democratic” are likely to “become frankly totalitarian” since a regime in which “the weakest go to the wall” and a “few capitalist owners” thrive “cannot be sustained except by violence, veiled if not open”.

Inaugurating India’s own experiment with an English-style parliament and electoral system, BR Ambedkar, one of the main authors of the Indian constitution, warned that while the principle of one-person-one-vote conferred political equality, it left untouched grotesque social and economic inequalities. “We must remove this contradiction at the earliest possible moment,” he urged, “or else those who suffer from inequality will blow up the structure of political democracy.”

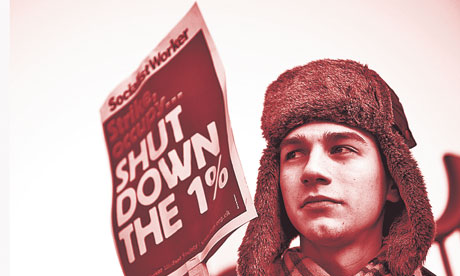

Today’s elected demagogues, who were chosen by aggrieved voters precisely for their skills in blowing up political democracy, have belatedly alerted many more to this contradiction. But the delay in heeding Ambedkar’s warning has been lethal – and it has left many of our best and brightest stultified by the antics of Trump and Johnson, simultaneously aghast at the sharpened critiques of a resurgent left, and profoundly unable to reckon with the annihilation of democracy by its supposed friends abroad.

Modi has been among the biggest beneficiaries of this intellectual impairment. For decades, India itself greatly benefited from a cold war-era conception of “democracy”, which reduced it to a morally glamorous label for the way rulers are elected, rather than about the kinds of power they hold, or the ways they exercise it.

As a non-communist country that held routine elections, India possessed a matchless international prestige despite consistently failing – worse than many Asian, African, and Latin American countries – in providing its citizens with even the basic components of a dignified existence.

It did not matter to the fetishists of formal and procedural democracy that people in Kashmir and India’s north-eastern border states lived under de facto martial law, where security forces had unlimited licence to massacre and rape, or that a great majority of the Indian population found the promise of equality and dignity underpinned by rule of law and impartial institutions, to be a remote, almost fantastical, ideal.

The halo of virtue around India shone brighter as its governments embraced free markets and communist-run China abruptly emerged as a challenger to the west. Modi profited from an exuberant consensus about India among Anglo-American elites: that democracy had acquired deep roots in Indian soil, fertilising it for the growth of free markets.

As chief minister of the state of Gujarat in 2002, Modi was suspected of a crucial role – ranging from malign inaction to watchful complicity – in an anti-Muslim pogrom of gruesome violence. The US and the European Union denied Modi a visa for several years.

But his record was suddenly forgotten as Modi ascended, with the help of India’s richest businessmen, to power. “There is something thrilling about the rise of Narendra Modi,” Gideon Rachman, the chief foreign affairs columnist for the Financial Times, wrote in April 2014. Rupert Murdoch, of course, anointed Modi as India’s “best leader with best policies since independence”.

But Barack Obama also chose to hail Modi for reflecting “the dynamism and potential of India’s rise”. As Modi arrived in Silicon Valley in 2015 – just as his government was shutting down the internet in Kashmir – Sheryl Sandberg declared she was changing her Facebook profile in order to honour the Indian leader.

In the next few days, Modi will address thousands of affluent Indian-Americans in the company of Trump in Houston, Texas. While his government builds detention camps for hundreds of thousands Muslims it has abruptly rendered stateless, he will receive a commendation from Bill Gates for building toilets.

The fawning by Western politicians, businessmen, and journalists over a man credibly accused of complicity in a mass murder is a much bigger scandal than Jeffrey Epstein’s donations to MIT. But it has gone almost wholly unremarked in mainstream circles partly because democratic and free-marketeering India was the great non-white hope of the ideological children of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher who still dominate our discourse: India was a gilded oriental mirror in which they could cherish themselves.

This moral vanity explains how even sentinels of the supposedly reasonable centre, such as Obama and the Financial Times, came to condone demagoguery abroad – and, more importantly, how they failed to anticipate its eruption at home.

Even the most fleeting glance at history shows that the contradiction Ambedkar identified in India – which enabled Modi’s rise – has long bedevilled the emancipatory promise of democratic equality. In 1909, Max Weber asked: “How are freedom and democracy in the long run at all possible under the domination of highly developed capitalism?”

The decades of atrocity that followed answered Weber’s question with a grisly spectacle. The fraught and extremely limited western experiment with democracy did better only after social-welfarism, widely adopted after 1945, emerged to defang capitalism, and meet halfway the formidable old challenge of inequality. But the rule of demos still seemed remote.

The Cambridge political theorist John Dunn was complaining as early as 1979 that while democratic theory had become the “public cant of the modern world”, democratic reality had grown “pretty thin on the ground”. Since then, that reality has grown flimsier, corroded by a financialised mode of capitalism that has held Anglo-American politicians and journalists in its thrall since the 1980s.

What went unnoticed until recently was that the chasm between a political system that promises formal equality and a socio-economic system that generates intolerable inequality had grown much wider. It eventually empowered the demagogues who now rule us. In other words, modern democracies have for decades been lurching towards moral and ideological bankruptcy – unprepared by their own publicists to cope with the political and environmental disasters that unregulated capitalism ceaselessly inflicts, even on such winners of history as Britain and the US.

Having laboured to exclude a smelly past of ethnocide, slavery and racism – and the ongoing stink of corporate venality – from their perfumed notion of Anglo-American superiority, the promoters of democracy have no nose for its true enemies. Ripe for superannuation but still entrenched on the heights of politics and journalism, they repetitively ventilate their rage and frustration, or whinge incessantly about “cancel culture” and the “radical left”, it is because that is all they can do. Their own mind-numbing simplicities about democracy, its enemies, friends, the free world, and all that sort of thing, have doomed them to experience the contemporary world as an endless series of shocks and debacles.