Our common treasury in the last 30 years has been captured by industrial psychopaths. That's why we're nearly bankrupt

Illustration by Daniel Pudles

If wealth was the inevitable result of hard work and enterprise, every woman in Africa would be a millionaire. The claims that the ultra-rich 1% make for themselves – that they are possessed of unique intelligence or creativity or drive – are examples of the self-attribution fallacy. This means crediting yourself with outcomes for which you weren't responsible. Many of those who are rich today got there because they were able to capture certain jobs. This capture owes less to talent and intelligence than to a combination of the ruthless exploitation of others and accidents of birth, as such jobs are taken disproportionately by people born in certain places and into certain classes.

The findings of the psychologist Daniel Kahneman, winner of a Nobel economics prize, are devastating to the beliefs that financial high-fliers entertain about themselves. He discovered that their apparent success is a cognitive illusion. For example, he studied the results achieved by 25 wealth advisers across eight years. He found that the consistency of their performance was zero. "The results resembled what you would expect from a dice-rolling contest, not a game of skill." Those who received the biggest bonuses had simply got lucky.

Such results have been widely replicated. They show that traders and fund managers throughout Wall Street receive their massive remuneration for doing no better than would a chimpanzee flipping a coin. When Kahneman tried to point this out, they blanked him. "The illusion of skill … is deeply ingrained in their culture."

So much for the financial sector and its super-educated analysts. As for other kinds of business, you tell me. Is your boss possessed of judgment, vision and management skills superior to those of anyone else in the firm, or did he or she get there through bluff, bullshit and bullying?

In a study published by the journal Psychology, Crime and Law, Belinda Board and Katarina Fritzon tested 39 senior managers and chief executives from leading British businesses. They compared the results to the same tests on patients at Broadmoor special hospital, where people who have been convicted of serious crimes are incarcerated. On certain indicators of psychopathy, the bosses's scores either matched or exceeded those of the patients. In fact, on these criteria, they beat even the subset of patients who had been diagnosed with psychopathic personality disorders.

The psychopathic traits on which the bosses scored so highly, Board and Fritzon point out, closely resemble the characteristics that companies look for. Those who have these traits often possess great skill in flattering and manipulating powerful people. Egocentricity, a strong sense of entitlement, a readiness to exploit others and a lack of empathy and conscience are also unlikely to damage their prospects in many corporations.

In their book Snakes in Suits, Paul Babiak and Robert Hare point out that as the old corporate bureaucracies have been replaced by flexible, ever-changing structures, and as team players are deemed less valuable than competitive risk-takers, psychopathic traits are more likely to be selected and rewarded. Reading their work, it seems to me that if you have psychopathic tendencies and are born to a poor family, you're likely to go to prison. If you have psychopathic tendencies and are born to a rich family, you're likely to go to business school.

This is not to suggest that all executives are psychopaths. It is to suggest that the economy has been rewarding the wrong skills. As the bosses have shaken off the trade unions and captured both regulators and tax authorities, the distinction between the productive and rentier upper classes has broken down. Chief executives now behave like dukes, extracting from their financial estates sums out of all proportion to the work they do or the value they generate, sums that sometimes exhaust the businesses they parasitise. They are no more deserving of the share of wealth they've captured than oil sheikhs.

The rest of us are invited, by governments and by fawning interviews in the press, to subscribe to their myth of election: the belief that they are possessed of superhuman talents. The very rich are often described as wealth creators. But they have preyed on the earth's natural wealth and their workers' labour and creativity, impoverishing both people and planet. Now they have almost bankrupted us. The wealth creators of neoliberal mythology are some of the most effective wealth destroyers the world has ever seen.

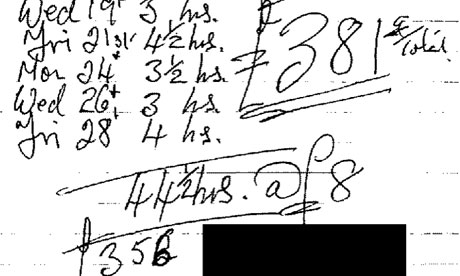

What has happened over the past 30 years is the capture of the world's common treasury by a handful of people, assisted by neoliberal policies which were first imposed on rich nations by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. I am now going to bombard you with figures. I'm sorry about that, but these numbers need to be tattooed on our minds. Between 1947 and 1979, productivity in the US rose by 119%, while the income of the bottom fifth of the population rose by 122%. But from 1979 to 2009, productivity rose by 80%, while the income of the bottom fifth fell by 4%. In roughly the same period, the income of the top 1% rose by 270%.

In the UK, the money earned by the poorest tenth fell by 12% between 1999 and 2009, while the money made by the richest 10th rose by 37%. The Gini coefficient, which measures income inequality, climbed in this country from 26 in 1979 to 40 in 2009.

In his book The Haves and the Have Nots, Branko Milanovic tries to discover who was the richest person who has ever lived. Beginning with the loaded Roman triumvir Marcus Crassus, he measures wealth according to the quantity of his compatriots' labour a rich man could buy. It appears that the richest man to have lived in the past 2,000 years is alive today. Carlos Slim could buy the labour of 440,000 average Mexicans. This makes him 14 times as rich as Crassus, nine times as rich as Carnegie and four times as rich as Rockefeller.

Until recently, we were mesmerised by the bosses' self-attribution. Their acolytes, in academia, the media, thinktanks and government, created an extensive infrastructure of junk economics and flattery to justify their seizure of other people's wealth. So immersed in this nonsense did we become that we seldom challenged its veracity.

This is now changing. On Sunday evening I witnessed a remarkable thing: a debate on the steps of St Paul's Cathedral between Stuart Fraser, chairman of the Corporation of the City of London, another official from the corporation, the turbulent priest Father William Taylor, John Christensen of the Tax Justice Network and the people of Occupy London. It had something of the flavour of the Putney debates of 1647. For the first time in decades – and all credit to the corporation officials for turning up – financial power was obliged to answer directly to the people.

It felt like history being made. The undeserving rich are now in the frame, and the rest of us want our money back.