'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Friday, 31 December 2021

Thursday, 30 December 2021

I’m a climate scientist. Don’t Look Up captures the madness I see every day

‘

‘ The movie Don’t Look Up is satire. But speaking as a climate scientist doing everything I can to wake people up and avoid planetary destruction, it’s also the most accurate film about society’s terrifying non-response to climate breakdown I’ve seen.

The film, from director Adam McKay and writer David Sirota, tells the story of astronomy grad student Kate Dibiasky (Jennifer Lawrence) and her PhD adviser, Dr Randall Mindy (Leonardo DiCaprio), who discover a comet – a “planet killer” – that will impact the Earth in just over six months. The certainty of impact is 99.7%, as certain as just about anything in science.

The scientists are essentially alone with this knowledge, ignored and gaslighted by society. The panic and desperation they feel mirror the panic and desperation that many climate scientists feel. In one scene, Mindy hyperventilates in a bathroom; in another, Diabasky, on national TV, screams “Are we not being clear? We’re all 100% for sure gonna fucking die!” I can relate. This is what it feels like to be a climate scientist today.

The two astronomers are given a 20-minute audience with the president (Meryl Streep), who is glad to hear that impact isn’t technically 100% certain. Weighing election strategy above the fate of the planet, she decides to “sit tight and assess”. Desperate, the scientists then go on a national morning show, but the TV hosts make light of their warning (which is also overshadowed by a celebrity breakup story).

By now, the imminent collision with comet Diabasky is confirmed by scientists around the world. After political winds shift, the president initiates a mission to divert the comet, but changes her mind at the last moment when urged to do so by a billionaire donor (Mark Rylance) with his own plan to guide it to a safe landing, using unproven technology, in order to claim its precious metals. A sports magazine’s cover asks, “The end is near. Will there be a Super Bowl?”

But this isn’t a film about how humanity would respond to a planet-killing comet; it’s a film about how humanity is responding to planet-killing climate breakdown. We live in a society in which, despite extraordinarily clear, present, and worsening climate danger, more than half of Republican members of Congress still say climate change is a hoax and many more wish to block action, and in which the official Democratic party platform still enshrines massive subsidies to the fossil fuel industry; in which the current president ran on a promise that “nothing will fundamentally change”, and the speaker of the House dismissed even a modest climate plan as “the green dream or whatever”; in which the largest delegation to Cop26 was the fossil fuel industry, and the White House sold drilling rights to a huge tract of the Gulf of Mexico after the summit; in which world leaders say that climate is an “existential threat to humanity” while simultaneously expanding fossil fuel production; in which major newspapers still run fossil fuel ads, and climate news is routinely overshadowed by sports; in which entrepreneurs push incredibly risky tech solutions and billionaires sell the absurdist fantasy that humanity can just move to Mars.

After 15 years of working to raise climate urgency, I’ve concluded that the public in general, and world leaders in particular, underestimate how rapid, serious and permanent climate and ecological breakdown will be if humanity fails to mobilize. There may only be five years left before humanity expends the remaining “carbon budget” to stay under 1.5C of global heating at today’s emissions rates – a level of heating I am not confident will be compatible with civilization as we know it. And there may only be five years before the Amazon rainforest and a large Antarctic ice sheet pass irreversible tipping points.

The Earth system is breaking down now with breathtaking speed. And climate scientists have faced an even more insurmountable public communication task than the astronomers in Don’t Look Up, since climate destruction unfolds over decades – lightning fast as far as the planet is concerned, but glacially slow as far as the news cycle is concerned – and isn’t as immediate and visible as a comet in the sky.

Given all this, dismissing Don’t Look Up as too obvious might say more about the critic than the film. It’s funny and terrifying because it conveys a certain cold truth that climate scientists and others who understand the full depth of the climate emergency are living every day. I hope that this movie, which comically depicts how hard it is to break through prevailing norms, actually helps break through those norms in real life.

We need stories that highlight the many absurdities that arise from knowing what’s coming while failing to act.

I also hope Hollywood is learning how to tell climate stories that matter. Instead of stories that create comforting distance from the grave danger we are in via unrealistic techno fixes for unrealistic disaster scenarios, humanity needs stories that highlight the many absurdities that arise from collectively knowing what’s coming while collectively failing to act.

We also need stories that show humanity responding rationally to the crisis. A lack of technology isn’t what’s blocking action. Instead, humanity needs to confront the fossil fuel industry head on, accept that we need to consume less energy, and switch into full-on emergency mode. The sense of solidarity and relief we’d feel once this happens – if it happens – would be gamechanging for our species. More and better facts will not catalyze this sociocultural tipping point, but more and better stories might.

Wednesday, 29 December 2021

Ashes long-con exposed: England's dereliction of Test cricket threatens format as a whole

As anyone who lived through the 2008 credit crunch will remember, economies are essentially built on confidence. So long as the public has faith in the robustness of the institutions charged with managing their assets, those assets barely need to exist beyond a few 0s and 1s in a digital mainframe for them to be real and lasting indicators of a nation's wealth.

When doubts begin to beset the system, however, it's amazing how quickly the rot can take hold. Is this really a Triple-A-rated bond I am holding in my hands, or is it actually a tranche of sub-prime mortgages that are barely fit to line the gerbil cage?

Likewise, is this really the world's most enduring expression of sporting rivalry taking place in Australia right now, or is it a pointless turkey shoot that exists only to justify the exorbitant sums that TV broadcasters are willing to cough up for the privilege of hosting it… a privilege that, in itself, feeds into the self-same creation myth that keeps the hype ever hyping, and the bubble ever ballooning.

On Tuesday, that bubble finally burst. After weeks of barely suppressed panic behind the scenes, England's capitulation in Melbourne deserves to be Test cricket's very own Lehman Brothers moment - the final, full-frontal collapse of an institution so ancient, and previously presumed to be so inviolable, that it may require unprecedented emergency measures to prevent the entire sport from tanking.

For there really has never been an Ashes campaign quite as pathetic as this one. Crushing defeats have been plentiful in the sport's long and storied history - particularly in the recent past, with England having now lost 18 of their last 23 Tests Down Under, including 12 of the last 13. But never before has an England team taken the field in Australia with so little hope, such few expectations, so few remaining skills with which to retain control of their own destinies.

Nothing expressed the gulf better than the performance of Australia's Player of the Match, Scott Boland. Leaving aside the rightful celebration of his Indigenous heritage, of far greater pertinence was his international oven-readiness, at the age of 32, after a lifetime of toil for Victoria in the Sheffield Shield. Like Michael Neser, 31 on debut at Adelaide last week and a Test wicket-taker with his second ball in the format, Boland arrived on the stage every bit as ready for combat as England's Test batters used to be - most particularly the unit that won the Ashes in Australia in 2010-11, which included four players with a century on debut (Alastair Cook, Andrew Strauss, Jonathan Trott and Matt Prior) and two more (Kevin Pietersen and Ian Bell) with fifties.

The contrast with England's current crop of ciphers could not be more galling. It is genuinely impossible to see how Haseeb Hameed could have been expected to offer more than his tally of seven runs from 41 balls across two innings at the MCG, while Ollie Pope's Bradman-esque average of 99.94 at his home ground at The Oval, compared to his cat-on-hot-tin-roof displays at Brisbane and Adelaide, is the most visceral evidence possible of a domestic first-class system that is failing the next generation.

Even on the second day at the MCG, England's best day of the series had finished with them four down for 31, still 51 runs in arrears, as Australia's quicks punished their opponents for a fleeting moment of mid-afternoon hubris by unleashing an hour of God-complex thunderbolts. It stood to reason that the morning's follow-up would be similarly swift and pitiless.

Watching a bowed and beaten troop of England cricketers suck up Australian outfield celebrations is nothing new, of course. But this is different to previous Ashes hammerings, because despite the Covid restrictions and limited preparation time, never before has a series loss felt further removed from the sorts of caveats that sustained previous such debacles Down Under - most particularly the 2006-07 and 2013-14 whitewashes, both of which were at least the gory dismemberments of England teams that had previously swept all before them.

The 2021-22 team, by contrast, has swept nothing before it, except a few uncomfortable home ruths under a succession of carpets. Despite the enduring magnificence of James Anderson - whose unvanquished defiance evokes Curtly Ambrose and Courtney Walsh's noble upholding of West Indies' crumbling standards at the turn of the millennium - and despite Joe Root willing himself to produce a year of such cursed brilliance it deserves to be inducted into Greek mythology, the rabble that clings to their coat-tails is little more than the zombified remains of the side that surrendered the urn so vapidly back in 2017-18.

They travelled to Australia with the same captain, for the first time on an Ashes tour in more than 100 years (and Root is destined for the same 5-0 shellacking that JWHT Douglas achieved in 1920-21); the same core bowling unit of right-arm medium-pacers, and by this third Test, the same outgunned middle order, with Root, Dawid Malan and Jonny Bairstow on this occasion physically united with Ben Stokes, compared to the spectre at the feast that had haunted the team's endeavours four years ago.

Nothing in the interim has progressed for this generation of players, in spite of a vast amount of hot air about how exhaustive the planning for this campaign has been - most particularly from England's dead-man-walking head coach, Chris Silverwood, whose epitaph deserves to be the same fateful phrase that he used to announce England's Test squad to face New Zealand at the start of the summer.

"The summer of Test cricket will be fascinating," Silverwood wrote back in May, shortly after he had taken over selection duties from Ed Smith to become the single most powerful supremo in the team's history. "Playing the top two teams in the world, in New Zealand and India, is perfect preparation for us as we continue to improve and progress towards an Ashes series in Australia at the back end of the year." Well, that aged well, didn't it?

And yet, Silverwood is just another symptom of English cricket's wider malaise. From the outset, and irrespective of his theoretical influence, he was only ever an uninspiring over-promotion from within the team's existing ranks - more than anything, a recognition of how undesirable the role of England head coach has become in recent years.

"All attempts to keep English Test cricket viable essentially ground to a halt from the moment that Tom Harrison was appointed as ECB CEO in 2015"

In an era of gig-economy opportunities on the T20 franchise circuit - when barely a day goes by without Andy Flower, the architect of England's last truly great Test team, being announced as Tashkent Tigers' batting consultant in the Uzbekistan Premier League - who wants or needs the 300-hotel-nights-a-year commitment required to oversee a side that, like an overworked troupe of stadium-rock dinosaurs, fears that the moment it takes a break from endless touring, everyone will forget they ever existed in the first place?

English cricket's financial reliance on its Test team has been holding the sport in this country back for generations, long before the complications of Covid kicked in to make the team's relentless touring lifestyle even less palatable than ever before. It was a point that Tom Harrison, the ECB chief executive, acknowledged in a moment of guard-down candour before last summer's series against India - and one that he will now be obliged to revisit with grave urgency as the sport lurches into a new crisis of confidence, but one that is effectively the reverse side of the same coin that the sport has been flipping all year long. English cricket's ongoing racism crisis, after all, is yet another damning expression of the sport's inability to move with the times.

"It is the most important series, then we've got another 'most important series' coming up, and then another directly after that," Harrison said of that India campaign - which, lest we forget, also needs to be completed next summer for the financial good of the game, even if the players would sooner move on and forget. "The reality is, for international players, is that the conveyor belt just keeps going. You want players turning up in these 'most important series' feeling fantastic about the opportunity of playing for their country. They are not going to be able to achieve that if they have forgotten the reasons why they play."

The issue for Harrison's enduring credibility, however, is that all attempts to keep English Test cricket viable essentially ground to a halt from the moment that he was appointed as CEO in 2015.

That summer's team still had the latent talent to seal the last of their four Ashes victories in five campaigns, but on Harrison's watch, the ECB has essentially spent the past six years preparing the life-rafts for the sport's post-international future - most notably through the establishment of the Hundred, but also through the full-bore focus on winning the 2019 World Cup, precisely because it was the sort of whiteboard-friendly "deliverable" that sits well on a list of boardroom KPIs… unlike the lumpen, intangible mesh of contexts by which success in Test cricket will always need to be measured.

It was a point that Root alluded to his shellshocked post-match comments, where he hinted that the red-ball game needed a "reset" to match the remarkable rise of the white-ball side from the wreckage of that winter's World Cup. But what do England honestly believe can be reset from this point of the sport's degradation?

It feels as though we've all been complicit in the long-con here. For 16 years and counting, the Ashes has been sold as the most glorious expression of cricket's noble traditions, when in fact that self-same biennial obsession has been complicit in shrinking the format's ambitions to the point where even England's head coach thinks that a magnificent home-summer schedule is nothing but a warm-up act.

Perhaps it all stems from the reductive ambitions of that never-to-be-forgotten 2005 series, the series upon which most of the modern myth is founded, but which was more of an end than a beginning where English cricket was concerned.

The summer of 2005 marked the end of free-to-air TV in the UK, the end of Richie Benaud as English cricket's voice of ages, the end of 18 years of Stockholm Syndrome-style subjugation by one of the greatest Test teams ever compiled. If English sport was to be repurposed as a series of nostalgic sighs for long-ago glories, then perhaps only Manchester United's "Solskjær has won it" moment can top it.

Sixteen years later, what are we left with? The dreadfulness of the modern Ashes experience has even bled into this winter's TV coverage, every bit as hamstrung by greedy decisions taken way above the pay-grade of the troops on the ground. It's symptomatic of a format whose true essence has been asset-stripped since the rivalry's heyday two decades ago, with those individual assets being sold back to the paying public at a premium in the interim.

It's not unlike a Ponzi scheme, in fact - a concept that English cricket became unexpectedly familiar with during a Test match in Antigua back in 2009, when the revelations about the ECB's old chum, Allen Stanford, caused a run on his bank in St John's, with queues stretching way further down the road that any stampede to attend a Caribbean Test match of recent vintage.

The warnings about Test cricket's fragility have been legion for decades. But if England, of all the Test nations, doesn't remember to care for the format that, through the hype of the Ashes, it pretends to hold most dear, this winter's experiences have shown that the expertise required to shore up those standards may not be able to survive much more neglect.

Saturday, 25 December 2021

What is Modi-Shah BJP’s ideology? You’re wrong if you say Right wing, because it’s Hindu Left

Prashant Kishor, who prefers to be described as a political aide rather than a strategist, which is generally the preferred usage for him, featured in our serious conversational show ‘Off The Cuff’ this week. Neelam Pandey, a senior member of our political reporting team at ThePrint, co-hosted it with me.

At some point, we asked him the question that’s always intrigued us. Does he have an ideology? Doesn’t that follow from the fact that he’s worked with Narendra Modi, Mamata Banerjee, Congress-SP (Uttar Pradesh, 2017), M.K. Stalin, Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy, Amarinder Singh and more?

To our surprise, he said no, I am not ideology-agnostic, you can call me Left-of-Centre. And then went on to elaborate what he meant, by using Mahatma Gandhi’s example. And so on. I noticed later, incidentally, that Kishor’s Twitter bio begins with the words “Revere Gandhi…”

His claim to a Centre-Left ideology set us thinking. What if we asked any of the other key political leaders the same question today? What is your ideology? Rahul and Priyanka Gandhi, Mamata Banerjee, Andhra’s Jagan, Tamil Nadu’s Stalin, Telangana’s KCR and so on. If any of them chooses to answer that question — the answer, honest or not, will be about the same. Everyone in Indian politics now wades in the waters of varying depth somewhere on the Left side of the pool. Nobody will say I stand on the Right.

Which brings us to the trick question. What would Narendra Modi’s answer be? We are, of course, making a brave and far-out presumption that he lets us or anyone ask him such a direct question: What’s your ideology, Prime Minister sir? Now, whether you are fan or a critic, chances are, your immediate response will be, of course the Right wing.

Over the past seven years since the Modi-Shah BJP has been in power, “Right wing” has become the widely accepted usage for the party, and the ideological forces behind it. We need to examine if this passes the test of facts. And fasten seat belts. Because, I will then make the case to you that what Modi and his BJP represent today is not a domineering national force of the Hindu Right. It is, on the other hand, the Hindu Left.

The Left-Right descriptors over time have become mixed up and confusing. In governance terms, the Right means first of all, social conservatism, strong religiosity, hard nationalism, low threshold for criticism, an authoritarian outlook. On all these parameters, the Modi government and today’s BJP pass the test of being Right wing. The reason I qualify it here is that we do not get caught in simplistic binaries. On all of these, this BJP and Modi are no different from, say, the Republicans in the US or the British Conservatives. Then, we enter contentious zones.

How do we, then come to our argument that the Modi-Shah-Yogi BJP is not a force of the pure Right or even the Hindu Right, but of the Hindu Left?

Check out the many steps the Modi government has taken on the economy in the past seven-plus years. For historical reference, look back at the previous BJP government under Atal Bihari Vajpayee. It made its commitment to getting the government out of business explicit, and set up a disinvestment ministry. When the party returned to power in 2014, you would have expected it to bring that ministry back. No such thing happened, although now there is a department, DIPAM, in the finance ministry with a full secretary.

It is only now that there is heady talk of disinvestment, but not so much has happened yet, with the sterling exception of Air India. Much other privatisation is still merely talk, or sleight of hand. As in, getting one public sector giant to acquire a smaller one, and the government, as the majority shareholder, cashing out to balance its deficit. But it is, as we had said in an earlier National Interest, like genius Milo Minderbender of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 trading with himself and making a profit. Of course, using the state’s products and cash.

Actually, this gets worse than a sleight of hand often enough. Think of the LIC, or even ONGC, being made to buy another PSU the government wants to ‘disinvest’ from. A bunch of money is paid out to the government. Our complaint isn’t that it disappears into that bottomless pit called the Consolidated Fund of India. If you believed in a market economy, you would have no complaint if the LIC or ONGC paid out dividends from its profits to its only, or overwhelming, shareholder, the government. But when the government makes them buy assets from it, these companies are not necessarily acting in the best interests of the policy holder or the minority shareholder. We are not saying that it always works out to their detriment, but the fact is these are not decisions these companies’ boards are taking with these non-sarkari shareholders’ interests at the top of their minds. This is a characteristic of the Left, not Right.

The Left is also known for handout economics, large, ambitious, welfare schemes involving redistribution of large chunks of the revenues. Which is precisely what the Modi government has been doing, from the MGNREGA it inherited to Gram Awas, toilet-building, Ujjwala, direct cash transfers to farmers and the poor, free grain and so on. Have you noticed, in fact, how muted as the opposition criticism of this governments’ Budgets has been?

There is some usual sniggering about being “pro-rich” etc. But everybody also notices that taxes on individuals now are the highest — almost 44 per cent — since reform began. Add to that an average of 18 per cent or so GST on goods and services that people, especially the rich, consume. The Left would applaud this. Of course, they’d want this to be even higher. Hopefully not the 97 per cent it was at Indira Gandhi’s socialist peak, when the foundation of the parallel black economy was laid.

An expanding, large, maai-baap (mom & dad) sarkar is something the Leftists love. See the expansion of our government in the Modi era. More and more Bhawans have come up in Delhi to accommodate a burgeoning government. Now the new Central Vista will create space for more. A comparison again with Vajpayee government. He had no hesitation selling the loss-making Lodhi Hotel in the heart of Delhi. An even bigger PSU dud was Hotel Janpath. Which, instead of being sold, has now become another set of offices and government accommodation. Samrat Hotel, next to Ashoka, ceased to be a hotel a long time ago. It has become a sarkari bhawan too. In fact, almost everyone here will be surprised when I tell you that even the new Lok Pal (do you remember we had appointed one? Okay, what’s his name?) has been given half a floor here.

Our taxes are higher than in a generation, our government is bigger than two generations and still growing, we ‘privatise’ our companies often by selling one PSU to another, now our government also decides for all of the country which Covid vaccine to have when, to be allowed boosters or not, and what can be sold in India. In a genuinely free market, there will be shops and buyers for Covaxin, Covishield, Sputnik, Pfizer and Moderna.

As with cars, consumers can choose a Maruti or a Mercedes. But not vaccines. Why? Because ours is a maai-baap sarkar. It is in no way a government of the economic Right. The Right is limited to religion and nationalism. The rest is as Left as the Congress or any other. The reason we call Modi-BJP ideology as the Hindu Left.

Friday, 24 December 2021

Thursday, 23 December 2021

Wednesday, 22 December 2021

Karnataka bill seeks to declare interfaith marriages involving conversion ‘null & void’

File photo of the Karnataka Assembly in Bengaluru. | PTI

File photo of the Karnataka Assembly in Bengaluru. | PTIIf passed by the Assembly in its current form, Karnataka’s anti-conversion bill will empower the state to deem interfaith marriages involving conversion “null & void”.

Karnataka Home Minister Araga Jnanendra Tuesday introduced a bill to regulate and penalise religious conversions in the state.

The Karnataka Protection of Right to Freedom of Religion Bill, 2021, known simply as the ‘anti-conversion bill’, has categorised as “allurements” the promise of marriage, free education, free medical treatment and jobs, and hence terms them unlawful reasons for religious conversion.

According to the bill, the term “religious convertor” will be applicable to anyone in the post of “Father, Priest, Purohit, Pandit, Moulvi or Mulla”.

Under the bill, a person planning to convert or a ‘convertor’ has to give a 30-day prior notice to the district magistrate about the conversion. A declaration is to be given even after conversion.

Those found guilty of converting others unlawfully can attract a punishment of three to five years in jail and a fine of Rs 25,000, the bill says. The punishment is higher if the converted person is a minor, a woman, person belonging to the Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes or “of unsound mind”.

Persons organising “mass conversions” are also liable to be punished.

Conversion to previous religion exempt

“The bill seeks to prohibit religious conversion by misrepresentation, force, undue influence, coercion, allurement or by any fraudulent means,” Karnataka Home Minister Jnanendra said while introducing the bill.

The bill also prohibits conversion for the purpose of marriage and seeks to deem such marriages void.

“Any marriage which has happened with the sole purpose of unlawful conversion or vice-versa by the man of one religion with the woman of another religion, either by converting himself before or after marriage or by converting the woman before or after marriage, shall be declared as null and void,” the bill states.

While the bill seeks to punish those involved and aiding “unlawful” religious conversion, it has been careful to exempt people reconverting to their “immediate previous religion”. People reconverting to their previous religion, in fact, won’t even be considered as ‘conversion’ under this law.

Free hand to raise objections, file complaint

The anti-conversion bill also frames voluntary religious conversion within a series of registration, notification, calls for objection and multiple rounds of enquiry.

The bill calls for all offences under the law to be non-bailable and cognisable, and defines “mass conversion” as an event where even two or more people are converted.

It gives anyone a free hand to raise objections and file complaints of suspected conversion.

“Any converted person, his parents, brother, sister or any other person who is related to him by blood, marriage or adoption or in any form associated or colleague may lodge a complaint of such conversion,” the bill reads.

While the bill doesn’t blanket-ban religious conversion, it makes the process to convert tedious, with options for anybody to file objections to an individual’s decision to convert.

Declaration before magistrate & after conversion

Any person wanting to convert to another religion or any convertor who wants to conduct a conversion should mandatorily make a declaration 30 days in advance to the district magistrate. Separate forms have been designed for this purpose.

The declaration is then notified on the notice board for public scrutiny, so that anybody might object. If any objection is received, an inquiry will be conducted through the revenue or social welfare department to ascertain the intention, purpose and cause of the proposed conversion, the bill says.

If the district magistrate concludes that the conversion is “unlawful”, police action will be initiated.

The bill also demands declaration after the fact of religious conversion.

Once again, a person who has converted will have to declare it before the magistrate within 30 days and it will be posted for public scrutiny on notice boards for anyone to object.

“The District Magistrate shall notify religious conversion on the notice board of the office of the District Magistrate and in the office of the Tahsildar and will call for objections in such cases where no objections were called earlier,” the bill says.

The declaration must contain personal details of the converted person — date of birth, permanent address, present place of residence, father’s/husband’s name, the religion to which the converted person originally belonged and the religion to which he has converted, the date and place of conversion and the nature of the conversion process, along with copies of ID cards or Aadhaar card.

The converted person will then have to appear before the magistrate in person. If objections are received the same enquiry procedure is followed to approve the conversion or deem it void.

If the enquiry concludes the conversion to be “lawful”, the person’s records are reclassified, which may affect his entitlement to grants and benefits under government schemes.

Quantum of punishment

The Bill puts women, minors and “persons of unsound mind” in the same category.

Under the bill, individuals converting others via “unlawful” means will attract punishment of three to five years in jail and a fine of Rs 25,000.

If the converted person is a minor, woman, a person belonging to the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes or “of unsound mind”, the punishment will be three to 10 years in prison, with a fine of Rs 50,000.

Those organising mass conversions “unlawfully” face three to 10 years in jail, with fine of Rs 1 lakh.

The bill demands that the ‘accused’ pay Rs 5 lakh compensation to the victim of a forced conversion, excluding the fine imposed by the courts. Repeat offences will attract a sentence of five years in jail and a fine of Rs 2 lakh.

The bill also proposes to stop all government aid and grants to institutions involved in “unlawful conversions”, apart from punishing the heads of such institutions.

The burden of proof of innocence will lie with the accused under the law, instead of the prosecution having to prove the offence.

Furthermore, the bill seeks to make anyone who has aided or abetted an offence under the law as “parties to the offence”, whether or not they themselves carried it out.

‘Unconstitutional’, says Opposition

The bill was met with severe opposition from the Congress and Janata Dal (Secular) (JD-S), who accused the government of trying to introduce the bill “on the sly”.

Karnataka Congress president D.K. Shivakumar even tore up copies of the bill, deeming it “unconstitutional” and accusing the government of sneaking the bill into the House without discussing it in the Business Advisory Committee or listing it as business of the House for Tuesday.

The bill was made part of the supplementary business for the afternoon session on Tuesday, right before the House reconvened.

“We oppose even the introduction of this bill that violates constitutional rights of citizens,” said Siddaramaiah of the Congress, leader of the Opposition.

Speaker of the Assembly Vishweshwara Hegde Kageri said the bill will be taken up for discussion Wednesday.

Monday, 20 December 2021

Sunday, 19 December 2021

Friday, 17 December 2021

Tuesday, 14 December 2021

Friday, 10 December 2021

Spending without taxing: now we’re all guinea pigs in an endless money experiment

Today, citizens are unwitting participants in a covert policy experiment. It embraces the idea of higher government spending without the necessity of increased taxes. While modern monetary theory (MMT), the doctrine, has obvious appeal for politicians, irrespective of economic religion, the long-term consequences may prove problematic.

A state, MMT argues, finances its spending by creating money, not from taxes or borrowing. As nations cannot go bankrupt when they can print their own currency, deficits and debt don’t matter. Accordingly, governments should spend to ensure full employment, guaranteeing a job for everyone willing to work. Alternatively, though not formally part of MMT, governments can fund universal basic income (UBI) schemes, providing every individual an unconditional flat-rate payment irrespective of circumstances.

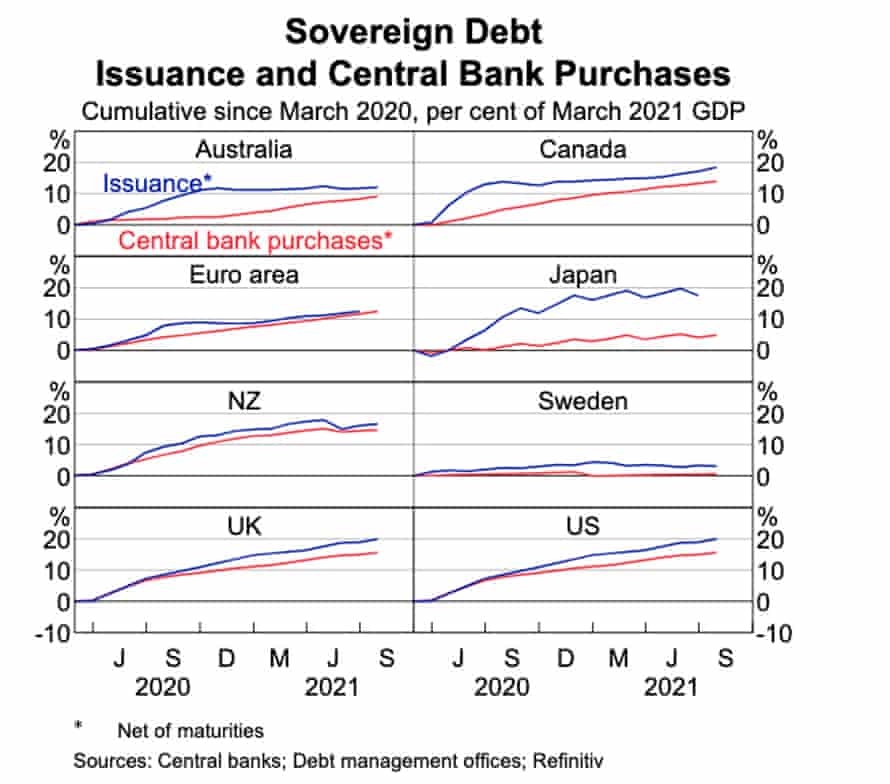

While no government or central bank overtly advocates MMT, since the 2008 global financial crisis and, more recently, the pandemic, policymakers have adopted many of its tenets by stealth. Popular one-off payments and increased welfare entitlements, which could become permanent, increasingly support economic activity. As the graph below highlights, central banks now buy a high percentage of new government debt, effectively financing this additional spending by money creation.

Source: Nick Baker, Marcus Miller and Ewan Rankin (2021 September) Government Bond Markets in Advanced Economies During the Pandemic; Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin

MMT is actually a melange of old ideas: Keynesian deficit spending; the post gold standard ability of nations to create money at will; and quantitative easing (central bank financed government spending) pioneered by Japan. However, there are several concerns about MMT.

First, the source of useful, well-compensated work is unclear. While MMT suggests taxes can be used to direct production, government influence over businesses that create jobs is limited. The impact of labour-reducing technology and competitive global supply chains is glossed over. Getting one person to dig a hole and another to fill it in creates employment, but it is of doubtful economic and social value. The woeful record of postwar centrally planned economies, where people pretended to work and the government pretended to pay them, highlights the issues.

Second, excess government spending and large deficits financed by money creation risk creating inflation. MMT argues that this is a risk only where the economy is at full employment or there is no excess capacity, and can be managed by fine-tuning intervention.

Third, MMT may weaken the currency. Roughly half of Australia’s government and significant amounts of state, bank and business debt is held by foreigners. Devaluation and loss of investor confidence in the stability of the exchange rate would affect the ability to and cost of borrowing overseas and importing goods. The expense of servicing foreign currency debt would rise.

Fourth, while available to nation states able to issue their own fiat currencies, it is unavailable to state governments, private businesses or households who are major borrowers in Australia.

Fifth, who decides the target employment rate or UBI payment level? Unemployment, inflation and output gaps are difficult to accurately measure in practice. Effects on employment incentives, workforce participation and productivity are untested. How will policymakers control the process or what would happen if MMT failed?

The theory delegates management of MMT operations to politicians, rather than unelected economic mandarins. But financially challenged elected representatives may be poorly equipped for the task. Political considerations and cronyism may influence decisions.

Sixth, there are implications for financial stability. Lower rates, the result of central bank debt purchases, and inflation fears might drive a switch to real assets, increasing the price of property and shares representing claims on underlying cashflows. It may encourage hoarding of commodities. This exacerbates inequality and increases the cost of essentials such as food, fuel and shelter. Fear of debasement of the value of paper money, in part, is behind unproductive speculation in gold and cryptocurrencies.

Seventh, MMT might undermine trust in the currency. Instead of spending the payments, citizens may question a world where governments print money and throw it out of helicopters.

Finally, Japan’s use of persistent deficits to boost short-term economic activity and incur government debt (currently more than 260% of GDP, compared with a global average of about 100%) does not prove the effectiveness of MMT. The country’s circumstances are unique and it has been mired in stagnation for three decades with its GDP largely unchanged.

MMT’s allure is the irresistible promise of freebies; full employment, unlimited higher education, healthcare and government services, state-of-the-art infrastructure, green energy and “the colonisation of Mars”. But monetary manipulation cannot change the supply of real goods and services or overcome resource constraints, otherwise prosperity and utopia would be guaranteed.

While the current game can and will continue for a time, the bill will eventually arrive. The borrowings will have to be paid for out of disposable income, higher taxes or through inflation, which reduces purchasing power, especially of the most vulnerable, and destroys savings. Other than nature’s free bounty, everything has a cost.

Thursday, 9 December 2021

Who will apologise for plasma therapy? It was a disaster for Covid-19, govt hospitals knew

Plasma therapy was administered to Covid-19 patients during the second wave in India | Wikipedia

Plasma therapy was administered to Covid-19 patients during the second wave in India | WikipediaThe closing pages of the 18th-century masterpiece fiction The Story of the Stone revealed the essence of the Tao’s message. In Lao Tzu’s words, it means that “Things are not as they seem, that the Eloquent may Stammer, that Perfection may seem Flawed, that Truth is Fiction, Fiction Truth.”

The truth is neither black nor white, it’s grey—the handling of the second wave of Covid-19 is a testimony to that fact.

Disaster that escaped public eye

In the midst of the second wave of Covid-19 with panic all around, a lot of therapeutic disasters were played out, and without a doubt, they were inspired by a lack of knowledge. Instead, they were fueled with a desire for one-upmanship and copycat fame. Some of the doctors unwittingly orchestrated this therapeutic mess. On one side, we had the armchair experts who were not running Covid-19 centres and had shut down their institutes. On the other, doctors in central government hospitals like the Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital in Delhi were running Out Patient Departments (OPDs) and wards. They were possibly following half-baked regimens with little proof, as there were lives at stake.

While some medications were possibly harmless and cheap like Ivermectin or HCQS, the others were ridiculously expensive, and no one was wiser about their efficacy. One of them was plasma therapy. Of course, the Indian medical system and healthcare did not have the time for a randomised trial to test a placebo. But the origin of the mess was thus created right here in the capital of the country.

One may ask—who would be the expert to decide on its efficacy? The clear answer is a clinician in a hospital, handling patients with an active plasma extraction centre. But what transpired is that a centre dedicated to liver care with nil experience in Covid-19 treatment proposed the idea that plasma might help. Then came the now-famous statement of Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal, saying that Delhi opened the first plasma bank in the world. That set off a chain reaction, and within a few weeks, hospitals followed suit.

It wasn’t the solution

Plasma is a component of the blood that is believed to have antibodies to diseases. Here, it was believed that Covid-19 patients would benefit from such therapy. This was when even the use of Intravenous immunoglobulin (IV IgG), a related plasma-based therapy that had been available for years, wasn’t effective in most disorders. This was also when we all knew that the so-called antibody tests of Covid-19 patients are negative or low positive. In fact, what is even more comical is that the quantity of antibodies in plasma is probably too little to do anything. And the ultimate irony is that therapy works in isolation, but here we had a plethora of medicines being administered, and it was not possible to pinpoint what was working behind the treatment.

Plasma does not come cheap, as it has to be extracted from patients. Thanks to the CM calling for plasma donation with great zeal and fanfare, the concept spread like wildfire. Intermediaries and ‘scamsters’ came in, and patients paid lakhs to get treatment, that too with dubious efficacy. Most doctors were inundated with calls for plasma, and we didn’t know what and where to arrange it for so many patients.

I know of patients who sold their belongings and went broke, partly because of plasma therapy and of course, Remdesivir, which has now been yanked off from all the guidelines. One of the members of our department, who had recovered from Covid-19, needed to give plasma to her own grandfather. He was admitted to the hospital, administered plasma but to no avail.

Trading fact for fame

Therefore, it is a must to understand the value of a placebo trial. Here, an identical-looking therapy is given to assess whether the active therapy—plasma, in this case—does anything substantial. A 30 per cent response rate is considered to be mostly placebo, or inactive, and that is the value of a placebo-controlled study.

There are numerous variables that determine the success of therapy in Covid-19, and assigning the credit to plasma showed a remarkable lack of foresight. At this juncture, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), in a multicentric study published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ), found that plasma wasn’t so good. But the public opinion swayed by the hospitals who pioneered the concept pilloried the paper and trashed it. Such was the distrust in our own country’s research that none wanted to get off the plasma bandwagon. Countless patients spent their life savings on what was a highly questionable therapy. And the charade continued till the second wave subsided.

The breakthrough

As always, we waited for a foreign journal to agree to a local finding, which was not surprising to a lot of us in the government hospitals. The landmark paper in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) showed that there was “No significant differences in clinical status or overall mortality between patients treated with convalescent plasma and those who received placebo.” It has been cited 455 times since it was published in February 2021. The number exceeds the citations of any of the papers published by the ‘experts’ who rolled out an untried therapy on the nation.

To add insult to injury, a section of the print media, which studiously avoided criticising them because their publications were the benefactors of full pages advertisements on plasma banks. To make it worse, some of the names suggested for the Padma awards this year included the plasma therapy pioneers.

Who takes the responsibility?

In retrospect, what needs to be asked is—who will pay for the loss of life savings and the death of patients who were given plasma therapy? Who will fill in the gaps for the distrust in medical care? Will the experts apologise? Who will apologise for pillorying the ICMR’s report that could have nipped this in the bud? But no one really apologises for such things in India.

As Donald Keough said, “The truth is, we are not that dumb and we are not that smart.” The plasma blitzkrieg was neither dumb nor smart; it was callous, and someone should be paying for the negligence today or tomorrow.

Pakistan can’t be Saudi Arabia or Iran. So it’s inching towards Talibanisation

Tragically, the dark days of General Zia’s brutality in Pakistan seem lighter today writes AYESHA SIDDIQA in The Print

A protest by Tehreek-e-Labbaik (TLP) supporters against the top court's verdict on Asiya Bibi

A protest by Tehreek-e-Labbaik (TLP) supporters against the top court's verdict on Asiya Bibi Thinking about the future of Afghanistan, especially in the last year, has been exhausting. You really begin to wonder what future are we looking at with the Taliban fairly in control of the country and the Islamic State, al-Qaeda and other militant groups present in other parts of Afghanistan. The marginally progressive, liberal and comparatively resourceful population has almost all fled the place. The scene of a State and society in tatters gnawed at my heart until I realised that socio-politically, Afghanistan is expanding into Pakistan too. While Islamabad claims the Taliban are inching towards pragmatism, Pakistan is moving towards the original formula of Talibanisation.

I am quite sure this will make the blood of many theoreticians boil, who would quickly point out that it’s flawed to mention Pakistan in the same breath as a failed country because it still has a functional bureaucracy, a strong military institution, and many systems that work. I am sure theoretical nuances wouldn’t have mattered to Priyantha Diyawadana as he was attacked and burned by a roaring crowd of Tehreek-e-Labbaik (TLP) supporters in Sialkot. The unfortunate man was just doing his duty as a general manager, asking the workers to clean the premises and remove all needless material from the walls that included TLP posters as the company was coming up for a foreign audit. To the jubilant young men, who took selfies with the burning body of the Sri Lankan manager, the State must have appeared like ashes to be stumped under the feet.

Those of us in Pakistan that get horrified at seeing photos of Taliban whipping women or beheading people, it would be educating to go and attend the court hearing in Sialkot to see that the average age of most suspects in the Diyawadana murder case appears to be under 30. Some will argue that though highly unfortunate, such violence happens around the world. This kind of view tends to shy from the reality that these young men (the suspects) are not just random miscreants but imagine themselves as a new force shaping up the face of the State and society. In their minds, they are taking the State in the direction that those who imagined Pakistan like Allama Iqbal, who wanted Islamic republicanism, would like — with a far heavier ideological colour than Pakistan’s national poet may have imagined. After all, didn’t the late TLP leader Khadim Rizvi constantly refer to Iqbal? This is not the story of a single murder but a natural outcome of the direction Pakistan’s identity is taking.

How religion shapes the State

I remember a conversation with renowned Pakistani scientist and activist Pervez Hoodbhoy during the 2000s when he was hopeful that the military would not let the situation get out of control and would harness the extremists it had produced to fight in Afghanistan and other fronts. Hoodbhoy imagined the military as a pragmatic and somewhat secular force. But the mistake was not only his as many policy wonks around the world had a similar view at the time– equating alcohol–consuming Generals with secularism. Many international observers also made the mistake of ignoring the fact that it was the pragmatism that would eventually kill Diyawadana and the Pakistani society along with him. The consistent use of religion to maximise power has stacked up the odds against any form of normality. Today, there is no one in Pakistan’s civil or military leadership who has the power to condemn the TLP directly. The current Army Chief, Qamar Javed Bajwa, with his controversial background is least capable of taking any action. It was Bajwa who had recently got a group of men together to negotiate a deal for the religious party to back down from its march towards Islamabad.

He was incapable of forcing his choice on the TLP mainly because he thought of the religious party as a useful tool for future purposes but also because many of his own men are tied to the ideological agenda of the issue of finality of the Prophet (Khatme Nabuwat) and blasphemy that TLP parrots. Furthermore, why forget that the TLP was trained in violence and allowed to get away with murders of police officials during their earlier protests against the Nawaz Sharif government. The army, instead of coming to the help of the civilian government, had encouraged and even participated in the violence and paid money to the TLP. In fact, the army played an instrumental role in diverting the urban trader-merchants away from the Deobandis to the Barelvis. Important to note that like the killer (Mumtaz Qadri) of former Punjab governor Salman Taseer was supported and helped by traders of Islamabad and Rawalpindi, sources said that the traders in Sialkot are providing assistance and moral help to lawyers pleading the case of those arrested in the Sri Lankan manager’s murder. In any case, the defence minister tried to downplay the violence as something ordinary.

Allama Iqbal was one leader who did not support the Khilafat movement but wanted an Islamic democracy where religious thought could be developed to shape the future of the State and society. He believed that ijma (consensus amongst religious scholars or community), which is an important source in Islamic jurisprudence, especially the principles that trickle down from companions of the Prophet, are not binding on future generations. The communal thought must be developed. The only problem with this formula was that while all efforts were made by successive Pakistani leaderships to create and emphasise the religious nature of the State, nothing was done to consciously develop the political discourse. As regimes kept developing religious institutions like the Federal Shariat Court, the Council of Islamic Ideology, the blasphemy laws, the Qisas and Diyat laws and much more, the State was allowed to keep using British laws and governance system. Every time a leader wanted to negotiate and bargain for more power, they would use religion as a tool and add to the cultural value of religion and in the process reiterate the significance of traditional ijma.

Not Iran or Saudi Arabia

Over the years, Pakistan has arrived at a point where we are neither like Saudi Arabia nor Iran. The absence of a monarchy makes it difficult for a ruler to impose a certain religious formula or change the direction of society towards less religion. More importantly, it does not have an alternative identity, which in the case of Saudi Arabia is being Arab, to fall back on to secure a sense of nationalism that does not depend on religion. Pakistan’s ruling elite consistently discouraged people from embracing multiple ethnic identities. Even Mohammad Ali Jinnah spoke about the ‘menace of provincialism’. While competing ethnic identities were discouraged, competing sectarian ideologies were encouraged. A religious State and society is the only natural direction but the problem is that, unlike Iran, Pakistan lacks a single faith. The presence of multiple competing sectarian ideologies complicates life. Thus, violence becomes a necessary tool through which various religious groups compete for greater influence. So, like the Taliban, use of force and violence will be used to impress the audience, control their imagination and maximise power.

However, there are the non-religious parties that may not compete in violence but are equally willing to use the popular religious narrative to compete politically. The issues of constituency politics has made the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI), Pakistan Muslim League–Nawaz (PML–N), or the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) all look alike as far as the religious card is concerned. They parrot the ideological position of Deobandi and now Barelvi religious gangs. Could the PPP — known as liberal and more capable than other parties to build legal/institutional mechanisms (the 18th amendment being a case in point) — provide an answer? Unfortunately, the party leadership has its limitations in the face of constituency politics as visible from its candidate in the Lahore bypolls using religion card as part of his campaign.

Religion as a negotiating and power maximising tool is used across the board – main political parties, ethnic nationalists, and even separatist movements. In Balochistan, for example, the Balochistan Nationalist Party and the Pashtunkhwa Milli Awami Party have joined hands with Maulana Fazlur Rehman to fight their battle for political survival. In another corner of the province in Gwadar, separatist leaders have instructed people to support Maulvi Hidayat-ur Rehman of Jamaat-e-Islami against the mainstream political parties or even Baloch nationalist parties that continue to subscribe to democratic principles for Baloch rights. It is heartening to hear about the progressive women marching for their rights in Gwadar. But a less talked about fact is that different mafias are aiding the maulvi, perhaps even playing to the tune of global China-US rivalry, in supporting Rehman to use the religion card for propaganda against Chinese clubs, wine factories and coastal city development in Gwadar. It is sad to see mullahs becoming the only available tool for locals to protest Chinese expansion. The fact that diverse political groups use the same tool – religion – is less a commentary about them and more a reflection on the nature of the State – it only has room for religion and religious narrative. One would have wanted it to turn into a Sunni Iran but to reiterate an earlier point, in the absence of a singular ideology it will only end up with more violence and chaos.

Tragically, the dark days of General Zia’s brutality seem lighter today. Particularly because a dissident then would land in Attock or Lahore Forts or any other State-run torture chambers. If one survived all of that, the person would get respect from society. Now, the fate of any dissident is as precarious as Diyawadana’s – the society cheers or remains silent to finish the job of the State that has almost made it a habit to feed its opponents to mob violence. It feels worse than Kabul.

Has Priti Patel stolen a leaf from BJP's playbook?

When the order was made to deprive Shamima Begum of her British citizenship in February 2019, it seemed gestural and unlikely to stand. She was born in England and had no dual nationality; her marriage to a Dutch citizen was invalid since she was 15 when she entered into it; and she had a baby, who was British by descent according to the British Nationality Act of 1981.

Within three weeks, her son had died, and the gesture had solidified into something darker and more concrete: a statement of values, in which some citizens are more British than others. What should be seen as chilling safeguarding issues – underage girls trafficked by criminal gangs into war zones – became security matters, in which the national interest is so profoundly threatened that, not only is the state relieved of its duty to protect, the girls can be made stateless.

Begum is not the only British citizen treated in this way. A recent Reprieve report details 20 British families stranded in north-east Syria, most of whom have had their citizenship removed. To divest us of any illusions, that these are freak occurrences for the monumentally unlucky, we now have the third reading of the nationality and borders bill. Forty-four members of the Scottish parliament signed an open letter to the home secretary, detailing what they considered to be its implications for asylum seekers – cruel measures to make already unsafe routes more treacherous – but noting, also, that it hangs “the threat of citizenship removal over naturalised British people in clear violation of international human rights agreements and basic principles of decency and fairness”.

Under the proposals, any foreign-born British citizen can be deprived of their citizenship, without notice or notification. Dual citizenship is not a precondition; they can be made stateless so long as the British government believes they are eligible for citizenship of another country. Analysis from the 2011 census, by the New Statesman, finds an astronomical number of people – 5.5 million in England and Wales – who fall into this category, including about 408,000 people born in the UK. It is hard to imagine a more flagrantly racist idea emanating from anywhere but a National Front manifesto: it affects half of British Asians and 39% of Black Britons.

This represents merely an acceleration of the Conservative agenda over the past decade. The Cameron years were more timid and underhand. The hostile environment policy of 2012, and the Windrush scandal it created, was openly racist, but limited in scope to one cohort. This in no way mitigated the injustice of it; to deprive one citizen of statehood, not to mention liberty, legal rights, healthcare, social security and the ability to work, is to deprive all. But it was a long time before it received due attention and protest, and victims are still waiting for restitution. That same year, the minimum income threshold of £18,600 was introduced for British citizens who wanted to bring a foreign spouse into the UK. The implications of this were, again, unremarked for a long time, but extraordinary; poor Britons thereafter had fewer rights as citizens than rich ones.

So citizenship was, from 2012, stratified by race and class. Full rights were enjoyed by a particular cross-section, and those outside it were newly precarious. Even if that insecurity were hypothetical – how many of us will, in the end, marry someone foreign born? How many are in the Windrush generation? – the principle was real, and ambient noise shored it up, not just Theresa May’s racist “Go Home” van but a fixation with shirkers and strivers, reinforcing a new conception of civic decency being a function of economic productivity.

Cameron’s government came to power, after its coalition fits and starts, on the back of a fiscal scarcity narrative that popularised austerity measures whose cruelty would have previously been unsellable. In power, the Conservatives have adjusted that scarcity so that it is no longer just money but also belonging that we don’t have enough of; there is simply not enough citizenship to go around, not enough nationhood, not enough human rights for the whole country to enjoy. Priti Patel may not need to repatriate your neighbours to nowhere today, but she needs to start knocking the legislation into shape, so that when the deportations begin, she knows who least belongs.

The question is not how likely it is that five and a half million Britons ever face deportation: it is, what political purpose does it serve to turn citizenship into a question not of unity but of hierarchy? It is more complex and intricate than simply sowing division and eroding solidarity; it generates emotional support for external xenophobia – against the EU, against refugees – by making the condition of Britishness a fragile one in which legitimacy is uncertain and loyalty must be continually demonstrated. The racism of the nationality and borders bill is not a Tory accident. It creates the conditions for their future successes and cover for their vast, unfolding errors; it’s up to all opposition parties to make sure it costs them more, electorally, than it can ever deliver.

Wednesday, 8 December 2021

Tuesday, 7 December 2021

The richest 10% produce half of greenhouse gas emissions. They should pay to fix the climate

This is not simply a rich versus poor countries divide: there are huge emitters in poor countries, and low emitters in rich countries writes Lucas Chancel in The Guardian ‘At current global emissions rates, the carbon budget that we have left if we are to stay under 1.5°C will be depleted in six years.’ Photograph: Friedemann Vogel/EPA

‘At current global emissions rates, the carbon budget that we have left if we are to stay under 1.5°C will be depleted in six years.’ Photograph: Friedemann Vogel/EPA

Let’s face it: our chances of staying under a 2C increase in global temperature are not looking good. If we continue business as usual, the world is on track to heat up by 3C at least by the end of this century. At current global emissions rates, the carbon budget that we have left if we are to stay under 1.5C will be depleted in six years. The paradox is that, globally, popular support for climate action has never been so strong. According to a recent United Nations poll, the vast majority of people around the world sees climate change as a global emergency. So, what have we got wrong so far?

There is a fundamental problem in contemporary discussion of climate policy: it rarely acknowledges inequality. Poorer households, which are low CO2 emitters, rightly anticipate that climate policies will limit their purchasing power. In return, policymakers fear a political backlash should they demand faster climate action. The problem with this vicious circle is that it has lost us a lot of time. The good news is that we can end it.

Let’s first look at the facts: 10% of the world’s population are responsible for about half of all greenhouse gas emissions, while the bottom half of the world contributes just 12% of all emissions. This is not simply a rich versus poor countries divide: there are huge emitters in poor countries, and low emitters in rich countries.

Consider the US, for instance. Every year, the poorest 50% of the US population emit about 10 tonnes of CO2 per person, while the richest 10% emit 75 tonnes per person. That is a gap of more than seven to one. Similarly, in Europe, the poorest half emits about five tonnes per person, while the richest 10% emit about 30 tonnes – a gap of six to one. (You can now view this data on the World Inequality Database.)

Where do these large inequalities come from? The rich emit more carbon through the goods and services they buy, as well as from the investments they make. Low-income groups emit carbon when they use their cars or heat their homes, but their indirect emissions – that is, the emissions from the stuff they buy and the investments they make – are significantly lower than those of the rich. The poorest half of the population barely owns any wealth, meaning that it has little or no responsibility for emissions associated with investment decisions.

Why do these inequalities matter? After all, shouldn’t we all reduce our emissions? Yes, we should, but obviously some groups will have to make a greater effort than others. Intuitively, we might think here of the big emitters, the rich, right? True, and also poorer people have less capacity to decarbonize their consumption. It follows that the rich should contribute the most to curbing emissions, and the poor be given the capacity to cope with the transition to 1.5C or 2C. Unfortunately, this is not what is happening – if anything, what is happening is closer to the opposite.

It was evident in France in 2018, when the government raised carbon taxes in a way that hit rural, low-income households particularly hard, without much affecting the consumption habits and investment portfolios of the well-off. Many families had no way to reduce their energy consumption. They had no option but to drive their cars to go to work and to pay the higher carbon tax. At the same time, the aviation fuel used by the rich to fly from Paris to the French Riviera was exempted from the tax change. Reactions to this unequal treatment eventually led to the reform being abandoned. These politics of climate action, which demand no significant effort from the rich yet hurt the poor, are not specific to any one country. Fears of job losses in certain industries are regularly used by business groups as an argument to slow climate policies.

Countries have announced plans to cut their emissions significantly by 2030 and most have established plans to reach net-zero somewhere around 2050. Let’s focus on the first milestone, the 2030 emission reduction target: according to my recent study, as expressed in per capita terms, the poorest half of the population in the US and most European countries have already reached or almost reached the target. This is not the case at all for the middle classes and the wealthy, who are well above – that is to say, behind – the target.

One way to reduce carbon inequalities is to establish individual carbon rights, similar to the schemes that some countries use to manage scarce environmental resources such as water. Such an approach would inevitably raise technical and information issues, but it is a strategy that deserves attention. There are many ways to reduce the overall emissions of a country, but the bottom line is that anything but a strictly egalitarian strategy inevitably means demanding greater climate mitigation effort from those who are already at the target level, and less from those who are well above it; this is basic arithmetic.

Arguably, any deviation from an egalitarian strategy would justify serious redistribution from the wealthy to the worse off to compensate the latter. Many countries will continue to impose carbon and energy taxes on consumption in the years to come. In these contexts, it is important that we learn from previous experiences. The French example shows what not to do. In contrast, British Columbia’s implementation of a carbon tax in 2008 was a success – even though the Canadian province relies heavily on oil and gas – because a large share of the resulting tax revenues goes to compensate low- and middle-income consumers via direct cash payments. In Indonesia, the ending of fossil fuel subsidies a few years ago meant extra resources for government but also higher energy prices for low-income families. Initially highly contested, the reform was accepted when the government decided to use the revenue to fund a universal health insurance and support to the poorest.

To accelerate the energy transition, we must also think outside the box. Consider, for example, a progressive tax on wealth, with a pollution top-up. This would accelerate the shift out of fossil fuels by making access to capital more expensive for the fossil fuel industries. It would also generate potentially large revenues for governments that they could invest in green industries and innovation. Such taxes would be politically easier to pass than a standard carbon tax, since they target a fraction of the population, not the majority. At the world level, a modest wealth tax on multimillionaires with a pollution top-up could generate 1.7% of global income. This could fund the bulk of extra investments required every year to meet climate mitigation efforts.

Whatever the path chosen by societies to accelerate the transition – and there are many potential paths – it’s time for us to acknowledge there can be no deep decarbonization without profound redistribution of income and wealth.

Monday, 6 December 2021

Looks fast, feels faster - why the speed gun is only part of the story

South Africa's Andrew Hall is on strike against Brett Lee at the Wanderers stadium in Johannesburg. The ball is bowled and Hall tucks it into the leg side before setting off for a gentle single.

As he jogs to the other end he hears a belated cheer from the crowd. Confused, he looks around to see the big screen displaying an announcement. He has just faced the fastest ball ever to have been bowled at the Wanderers.

Still confused, Hall's eyes move from the screen to Lee and they trade a quizzical look: "There's no way that was that quick."

The next ball, Lee runs in and bowls a bouncer to Gary Kirsten that flies past his face. Lee and Hall catch each other's eye once more,

"That one was."

You see, the speed gun is the movie adaptation of your favourite book. Yes, it tells the story. But it doesn't tell the full one.

****

"A lot of what makes Test players special happens before the ball comes out of a bowler's hand."

Those are the words of England analyst Nathan Leamon, speaking on Jarrod Kimber's Red Inker podcast. As a starting point, it shines a light on one of the limitations of the speed gun. It only tells us how fast a ball is at the point of release and tells us nothing about what has happened before or what happens after.

And what happens before is crucial. It is very easy to think of facing fast bowling as primarily a reactive skill. In fact, read any article on quick bowling and it will invariably say you only have 0.4 seconds to react to a 90mph delivery.

But what does that mean? No one can compute information in 0.4 seconds. It's beyond our realm of thinking in the same way that looking out of an aeroplane window doesn't give you vertigo because you're simply too high up for your brain to process it.

However, the reason it's possible is because, whilst you may only have 0.4 seconds to react, you have a lot longer than that to plan. And the best in the world plan exceptionally well.

Hall describes a training method that South Africa would use in order to be able to associate a bowler's release point with length. After a ball was bowled, they'd walk down the wicket and place a cone or mark a spot with their bat where they believed the ball had landed. The coach would confirm it or correct what the player thought.

The idea is in essence basic trigonometry. Over time, you learn to associate that if a bowler releases the ball with his arm at 12 o'clock, the delivery would be full. If he releases the ball at 1 o'clock, it would be short. It's a process designed to consciously train the subconscious, and Jacques Kallis was the best at it.

"Whether he played and missed," Hall says, "or left it, or ducked out the way, he'd be able to come down the track and isolate a rough area of where that ball had landed. And the reason he was so good at it is he became really sharp at picking up length and he made some bowlers look slower because of that. Because as they let go of the ball, he knew within a couple of inches where it was going to land."

Jasprit Bumrah roars after having Joe Root caught in the slips AFP/Getty Images

Jasprit Bumrah roars after having Joe Root caught in the slips AFP/Getty ImagesThere are a number of pre-delivery cues that Hall, as an international player, would be looking out for. Some were obvious tells, such as a bowler running in that bit harder before bowling a bouncer; others more subtle, like a bowler's head falling away in their action so they were able to push the ball into the batter and bowl an inswinger.

These cues weren't restricted to fast bowlers either. When talking about how to face Muthiah Muralidaran, Hall explains that one of the cues the South Africans would look out for was where his right elbow would be pointing as he entered his delivery stride. If it was pointing out at 90 degrees with his hand by his ear lobe, that was the sign that Muralitharan was going to bowl his off-spinner. If his elbow was pointing down towards the batter, it was probably a doosra coming up.

"You still wouldn't be able to play it half the time," Hall adds, "but you had an idea."

And some bowlers give you more of these cues than others, meaning a bowler at 87mph may feel quicker than one at 90mph if they give the batter fewer clues in their action.

Mark Ramprakash spoke of this when comparing his experience of facing Lee and Jason Gillespie in the 2001 Ashes. Lee was the faster bowler of the two, but his textbook action, with the ball always in sight, meant that Ramprakash felt he could consistently time his pre-delivery movement. But when he faced Gillespie, despite his being slower on the speed gun, it felt quicker. And this was because Gillespie would appear almost to release the ball before he'd really landed on the ground, throwing off Ramprakash's timings. When facing Lee, Ramprakash was planning. But when he was facing Gillespie, he was reacting.

In simple terms, there's a correlation between a bowler being "different" and the feeling that they are faster than they actually are. Batters are brought up on a diet of right-arm-over bowling that is released from nigh-on the same area, ball after ball after ball. Remove that familiarity, and the feeling of speed goes up.

In the Caribbean in 2019, TV showed Jasprit Bumrah's release point was half a metre closer to the batter than Kemar Roach's. This gave Bumrah the effect of bowling 3.7mph faster than the speed gun was showing

"Take Lasith Malinga," Hall says. "If you've not faced him before, you're literally going 'what am I supposed to watch?' But you soon get told, when he gets into his action, to watch the umpire's chest and neck. If you're watching his arm, you're struggling. And that's why in the beginning he'd clean people up and they'd say 'ah, he's quick'. He's not that quick. You just couldn't follow the ball."

****

Another quirk of how we consider pace is that by measuring the speed at which a ball is released, we're not actually measuring how long it takes to reach the batter. And there's a difference.

For instance, if you set up a bowling machine at 85mph and deliver three balls in a row, one of which is a full toss, the second a good length delivery and the third a bouncer, each of the three balls will reach the other end in a different amount of time because when the ball hits the pitch, it slows down. And the steeper that impact is, the more it will slow. So counterintuitively, the bouncer, cricket's scariest delivery, is actually the slowest of the three, whereas the full toss, cricket's worst delivery, is the fastest.

But what we don't know is how different bowlers compare to each other in terms of how much pace they lose off the wicket. The information is out there, but it's just not readily available. Angus Reid from VirtualEye - the company that provides ball-tracking data for Test matches in Australia - recalls how, during Naseem Shah's Test debut for Pakistan, they did a piece for broadcast comparing how he and Australia's Pat Cummins were releasing the ball at very similar speeds, but Shah was reaching the batter faster due to a combination of his height, ball trajectory and "skiddy" nature.

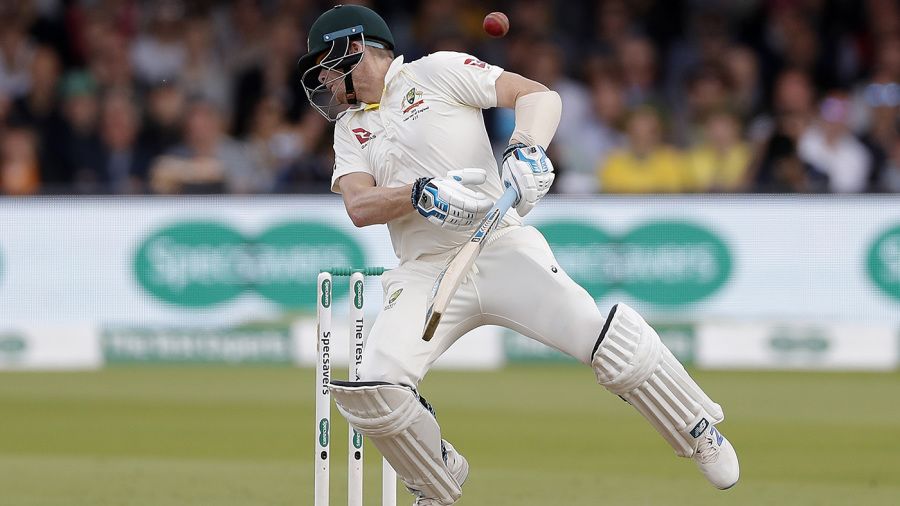

Steven Smith was pinned by a Jofra Archer bouncer at Lord's in 2019 Getty Images

Steven Smith was pinned by a Jofra Archer bouncer at Lord's in 2019 Getty ImagesAnd we know from player anecdotes that these things matter. Hall explains how bowlers will sometimes bowl their bouncer with a cross-seam in the hope that the ball lands on the lacquer and loses less pace when it pitches. It is the same notion that Joe Root expressed earlier this year when he said India's spinner Axar Patel was beating England for pace in the pink-ball Test at Ahmedabad, because the skid off the lacquer gave the feeling that the ball was "gathering pace" off the wicket.

Conversely, many bowlers are said to bowl a "heavy ball", whereby batters feel that the ball is "hitting the bat harder" than expected. One such bowler was New Zealand bowler Iain O'Brien, who believes this was a consequence of the ball kicking up off the pitch and striking the blade higher than anticipated, due to more backspin being imparted upon release. Such was the backspin that Andrew Flintoff imparted on the ball, in the lead up to the 2005 Ashes he was accused of chucking as his wrist would snap so dramatically at the point of delivery.

This is one of the difficulties of trying to express the feeling of speed to a wider audience. For the spectator, it's merely a number because we have no other frame of reference. But for the batter, it's an experience. A moment in time that is almost over before it's begun.

One former international cricketer laughed when asked whether he would check the speed gun after facing a delivery. "Why would I need the speed gun to tell me if a ball was fast? I was the one who just faced it."

****

The final piece of the puzzle concerns the ball's release point.

When India were touring the Caribbean in 2019, TV showed an overlay of Jasprit Bumrah's release point compared to Kemar Roach's, demonstrating that Bumrah was bowling the ball half a metre closer to the batter than Roach. Some quick maths showed that this gave Bumrah the effect of bowling 3.7mph faster than the speed gun was showing. Cricket has long been played on a pitch that is 22 yards. Bumrah plays on one that is 21.5.

Admittedly, this advantage was spotted because Bumrah is on the extreme, gazillion-jointed end of the scale, enabling him to bowl closer than anyone else in a way that other bowlers can't. But given we pay attention to how wide on the crease a bowler will bowl and also how high a bowler's release point is, surely we should know how close a bowler is bowling to the batter, given it is the single easiest way of apparently increasing pace.

This effect is measured in baseball. In fact, everything is. While cricket shrugs its shoulders and says "I guess we'll never know, folks" for a myriad of data-points, every intangible detail in baseball is known and measured.